Unhealthy Coping: Smoking and Drinking Behaviors and Related Risk Factors Among Dementia Caregivers

by Jiaming Liang1,3*, Maria P. Aranda2,3

1School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. 7411 John Smith Dr, San Antonio, TX, 78229, USA (This is the affiliation where the study was carried out)

2Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California. 669 W 34th St, Los Angeles, CA, 90089, USA

3Edward R. Roybal Institute on Aging, University of Southern California. 669 W 34th St, Los Angeles, CA, 90089, USA

*Corresponding author: Jiaming Liang, School of Public Health, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. 7411 John Smith Dr, San Antonio, TX, 78229, USA

Dementia Caregivers. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8:1640. DOI: 10.29011/2688-9501.101640

Received Date: 02 May 2025

Accepted Date: 12 May, 2025

Published Date: 15 May, 2025

Citation: Liang J and Aranda MP (2025) Unhealthy Coping: Smoking and Drinking Behaviors and Related Risk Factors Among Dementia Caregivers. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8:1640. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-9501.101640

Abstract

Background: Dementia caregivers often experience high levels of stress, which may contribute to unhealthy coping behaviors such as smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption. However, little is known about the extent of these behaviors among caregivers and whether certain subgroups are at elevated risk. Methods: This study analyzed data from the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to compare tobacco smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption between dementia caregivers (n = 511) and non-caregivers (n = 19,402). Multinomial and zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were used to examine associations between caregiving status, sociodemographic characteristics, and the unhealthy coping behaviors. Results: Dementia caregivers and non-caregivers exhibited similar overall rates of smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption. However, significant interactions revealed that low-income (RRR = 7.03, p = 0.001) and unemployed (RRR = 4.89, p = 0.03) dementia caregivers were more likely to smoke daily, while unmarried caregivers consumed more alcohol per drinking day (IRR = 2.23, p = 0.04). Female (RRR = 1.96, p < 0.001) and Asian (RRR = 5.44, p < 0.001) dementia caregivers had significantly higher odds of daily e-cigarette use, suggesting cultural and stress-related influences on coping behaviors. Conclusions: These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions and policies to address tobacco smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption among dementia caregivers, particularly those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged and from minority populations.

Keywords: Dementia Caregiving; Smoking; Alcohol Drinking; Stress and Coping; Health Disparities

Introduction

Dementia affects approximately 6.5 million people in the US, the number is expected to grow to 13.8 million by 2050, which will increase the demand for caregiving [1]. Family caregivers provide about 80% of dementia care, often performing over 90% of caregiving hours in community settings [2]. However, family caregivers are often the “hidden victims” of dementia, experiencing high stress, physical exhaustion, financial burden, and social isolation, which can negatively impact their physical and mental health, including higher cardiometabolic risks, more chronic pain, depression and anxiety [3-5]. This distress can further deteriorate caregiver relationships with persons living with dementia (PLWD), lowering the quality of care [6]. Thus, understanding these stressors and developing supportive interventions are imperative to alleviate caregiver burden and improve their well-being.

Stress and Maladaptive Coping

The Stress and Coping Model explains how family caregivers appraise stress and select coping strategies in response to caregiving demands [7]. Family caregivers may choose maladaptive emotionfocused coping, such as denial, avoidance, and toxic positivity, when they feel overwhelmed by the caregiving demands and lack of control over the situation [8]. This type of coping may provide temporary emotional relief, but also can lead to negative longterm health outcomes [9]. Previous research has identified that caregivers with higher caregiving burden, lower socioeconomic status, limited social support, and poor physical health are more prone to unhealthy behaviors like smoking, binge drinking, and poor dietary habits, which further exacerbate their stress and health decline [10-12]. Therefore, it is essential to identify risk factors for negative coping behaviors among dementia caregivers to provide tailored support that equips them with the necessary resources and more adaptive coping strategies.

Smoking and Alcohol Use Among Dementia Caregivers

Previous studies suggest that dementia caregivers are at a higher risk of smoking and alcohol consumption compared to non-caregivers, though findings vary by specific behaviors and caregiver characteristics [13,24]. While dementia caregivers and non-caregivers report similar levels of heavy alcohol use, adult children and those providing fewer daily caregiving hours exhibit higher prevalence [24]. Additionally, younger dementia caregivers show higher smoking rates compared to older caregivers, who report lower smoking rates than the general population [14]. The mechanisms behind these behaviors are complex, as not all caregivers rely on smoking or alcohol for stress relief [15,16]. These variations underscore the complexity of these behaviors and the need for research that accounts for sample differences to identify high-risk groups.

This study also examines e-cigarette use among dementia caregivers, given its rising popularity and potential health risks [17] E-cigarette use among U.S. adults reached 4.5% in 2021, with health risks including lung injury, cardiovascular disease, and nicotine dependence [18-20]. However, there is limited research on e-cigarette use and the related factors among dementia caregivers. Identifying its prevalence among dementia caregivers is crucial because these products are often marketed as less harmful alternatives to traditional tobacco and may be more appealing to caregivers seeking perceived lower-risk coping strategies [21].

The Current Study

In summary, individuals’ coping behaviors are shaped by various factors, including age, gender, education level, income, and social support. When these background factors intersect with dementia caregiving, the impact on coping strategies can be more pronounced. For example, dementia caregivers with low socioeconomic status tend to exhibit higher rates of physical inactivity due to limited supportive resources [22], while those with poor mental health report greater tendencies toward poor dietary habits [23]. Thus, this exploratory study investigates two research questions: a) how do dementia caregivers’ rates of smoking tobacco, e-cigarette use, and alcohol drinking compared to non-caregivers? And b) what demographic, socioeconomic, and health contextual factors contribute to increased smoking and drinking behaviors among dementia caregivers?

This study is crucial for improving understanding of coping patterns among dementia caregivers and identifying subgroups at higher risk of adopting unhealthy behaviors. By identifying contributors to smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption, results can inform tailored interventions and policy strategies to mitigate health disparities and improve support for dementia caregivers.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a cross-sectional analysis utilizing data from the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationwide health-related telephone survey conducted annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that collects data on health behaviors, chronic conditions, and the use of preventive services. It includes both core modules, which are asked across all states, and optional modules, which states can choose based on local priorities [25]. In 2017, five states (Alaska, Hawaii, New Mexico, Oregon, and Rhode Island) including 28,479 records that administered the modules on tobacco and e-cigarettes use, alcohol consumption, caregiving, and chronic health-related conditions.

Data

This study compares dementia caregivers and non-caregivers on tobacco, e-cigarette, and alcohol use. An examination of missing data on key variables revealed an overall missing rate of 4.8%, with only 0.1% missing among dementia caregivers; thus, cases with missing values were excluded without imputation [26]. The final sample comprised 19,813 respondents, including 19,402 noncaregivers and 511 dementia caregivers.

Measurements

Outcome variables: Tobacco and e-cigarette use were classified into four ordinal categories: every day smoker, some-day smoker (within the past 30 days), former smoker (quit), and never smoker. Alcohol consumption was measured using two numeric variables: the number of alcohol drinking days in the past 30 days and the average number of drinks consumed per drinking day (with 1 drink defined as a 12-ounce beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a drink containing one shot of liquor).

Dementia caregiving status: Dementia caregivers were identified through BRFSS caregiving module responses. Participants who provided care for a family member or friend due to dementia and other cognitive impairment disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were classified as dementia caregivers.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants included: age (18-54, 55-64, 65-74, and 75+ years), sex (female/male), race/ ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and others), marital status (married/not married), education level (high school or below, some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher), housing status (own, rent, and other arrangements), employment status (employed, unemployed, and retired), annual household income (<$25,000, $25,000-$50,000, and >$50,000).

Health characteristics. Self-rated health was assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from poor to excellent and, following established categorization methods [27], was classified as good/better versus fair/poor. Depression was determined by self-reported diagnosis of a depressive disorder (yes/no). The number of chronic conditions was based on the presence of 12 chronic diseases, including hypertension, high cholesterol, heart attack, coronary heart disease, stroke, asthma, skin cancer, other types of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), arthritis, kidney disease, and diabetes.

Analytic Strategies

All analyses were conducted using Stata 18 [28]. BRFSS sampling weights were applied to account for the complex sampling design [39], to generalize estimates from 19,813 participants to a weighted population of 4,943,993 across five selected states. Descriptive statistics were calculated, stratified by dementia caregiving status, with categorical variables reported as frequencies/percentages and continuous variables as means/standard deviations (SDs). Bivariate comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Multinomial logistic regression models examined tobacco and e-cigarette use, with “never smoker” as the reference group, estimating relative risk ratios (RRRs) for other smoking patterns. These models were adjusted for dementia caregiving status, sociodemographic factors, and health characteristics. Interaction terms between caregiving and each predictor were tested in follow-up models. For significant interactions, predicted outcome values were estimated, with figures illustrating group differences. For example, if the interaction between dementia caregiving and sex was significant in the model comparing the RRR of everyday smokers to never smokers, predicted RRR values were estimated for female non-caregivers, female dementia caregivers, male noncaregivers, and male dementia caregivers.

Two zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models analysed the number of drinking days in the past 30 days and the average number of drinks per drinking day. The ZINB models addressed the high frequency of zero values and over-dispersion [29]. Similar to the smoking models, interaction terms examined whether dementia caregiving status increased the risk of alcohol consumption across sociodemographic and health backgrounds.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study sample included 19,813 participants, of whom 511 were dementia caregivers. After applying sampling weights, the sample represents approximately 5 million people, including 112,750 dementia caregivers (Table 1). Dementia caregivers significantly differed from non-caregivers in several sociodemographic and health characteristics. Dementia caregivers were older, with a higher proportion aged 55 years and older (40.9% vs. 51.5%; χ² = 32.15, p < 0.001), predominantly female (62.9% vs. 49.7%; χ² = 30.60, p < 0.001), and more likely to self-identify as Asian (12.5% vs. 8.7%) or other racial/ethnic groups (13.6% vs. 9.5%; χ² = 38.87, p < 0.01). Due to sampling limitations, no Black participants were identified in the dementia caregiver group; thus, subsequent analyses do not assess racial differences for this group. Dementia caregivers were more likely to be married (68.2% vs. 55.5%; χ² = 28.98, p < 0.01), and homeowners (83.9% vs. 66.9%; χ² = 59.07, p < 0.001). They also reported greater health burdens than non-caregivers, including higher rates of fair or poor selfrated health (12.5% vs. 17.4%; χ² = 7.77, p < 0.05), depression (23.8% vs. 19.9%; χ² = 13.64, not significant), and more chronic conditions (1.62 vs. 1.34; t = 3.42, p < 0.01).

Dementia caregivers showed similar patterns in smoking and e-cigarette use compared to non-caregivers. Although not statistically significant, dementia caregivers had higher rates of everyday smoking (14.8% vs. 10.1%) and former smoking (28.3% vs. 26.7%), with fewer never smokers (54.1% vs. 58.4%). E-cigarette use patterns were nearly identical between caregivers (1.8%) and non-caregivers (1.8%). Alcohol consumption is also similar, with dementia caregivers reporting a slightly fewer drinking days in the past 30 days (4.95 vs. 5.58 days; t = 1.23, not significant), and fewer drinks per day (1.23 vs. 1.37; t = 0.85, not significant).

|

Non-caregivers |

Dementia caregivers |

X2 / (t) |

||||||||

|

Unweighted |

Weighted |

Unweighted |

Weighted |

|||||||

|

N = 19,402 |

N = 4,831,243 |

N = 511 |

N = 112,750 |

|||||||

|

f / (M) |

% / (SD) |

f / (M) |

% / (SE) |

f / (M) |

% / (SD) |

f / (M) |

% / (SE) |

|||

|

Outcomes |

||||||||||

|

Tobacco use status |

Everyday |

570 |

0.058 |

485809 |

0.1011 |

19 |

0.0679 |

16674 |

0.1482 |

15.31 |

|

Some days |

381 |

0.0387 |

230421 |

0.048 |

6 |

0.0214 |

3109 |

0.0276 |

||

|

Former user |

2973 |

0.3023 |

1279885 |

0.2665 |

87 |

0.3107 |

31811 |

0.2828 |

||

|

Never |

5912 |

0.6011 |

2806897 |

0.5844 |

168 |

0.6 |

60903 |

0.5414 |

||

|

E-cigarettes use status |

Everyday |

110 |

0.0111 |

85562 |

0.0177 |

5 |

0.0179 |

2124 |

0.0188 |

7.43 |

|

Some days |

153 |

0.0155 |

107754 |

0.0223 |

4 |

0.0143 |

2754 |

0.0244 |

||

|

Former user |

1216 |

0.1232 |

828783 |

0.1718 |

29 |

0.1036 |

13880 |

0.1231 |

||

|

Never |

8388 |

0.8501 |

3803006 |

0.7882 |

242 |

0.8643 |

93992 |

0.8336 |

||

|

Days had alcohol in past 30 days [0-30] |

-7.06 |

-9.61 |

-5.58 |

-0.09 |

-5.84 |

-8.76 |

-4.95 |

-0.51 |

-1.23 |

|

|

Number of drinks per timea [0-47] |

-1.38 |

-2.08 |

-1.37 |

-0.03 |

-1.21 |

-2.69 |

-1.23 |

-0.16 |

-0.85 |

|

|

Demographics |

||||||||||

|

Age |

18-54 |

4385 |

0.4487 |

2818733 |

0.5901 |

90 |

0.3273 |

53959 |

0.4844 |

32.15** |

|

55-64 |

2081 |

0.2129 |

824613 |

0.1726 |

84 |

0.3055 |

30041 |

0.2697 |

||

|

65-74 |

2189 |

0.224 |

667225 |

0.1397 |

67 |

0.2436 |

15795 |

0.1418 |

||

|

75+ |

1118 |

0.1144 |

465826 |

0.0975 |

34 |

0.1236 |

11597 |

0.1041 |

||

|

Sex (female) |

5009 |

0.5073 |

2399813 |

0.4972 |

175 |

0.6272 |

70755 |

0.6286 |

30.60** |

|

|

Race/Ethnicity |

Non-Hispanic White |

6328 |

0.6508 |

2903529 |

0.6124 |

173 |

0.6314 |

70219 |

0.6386 |

38.87** |

|

Non-Hispanic Black |

117 |

0.012 |

106024 |

0.0224 |

0 |

0 |

772 |

0.007 |

||

|

Hispanic |

1018 |

0.1047 |

866202 |

0.1827 |

21 |

0.0766 |

10236 |

0.0931 |

||

|

Asian |

938 |

0.0965 |

413110 |

0.0871 |

35 |

0.1277 |

13768 |

0.1252 |

||

|

Others |

1322 |

0.136 |

452694 |

0.0955 |

45 |

0.1642 |

14969 |

0.1361 |

||

|

Socioeconomic characteristics |

||||||||||

|

Marital status (married) |

5719 |

0.5813 |

2665334 |

0.5551 |

185 |

0.6607 |

76623 |

0.6822 |

28.98** |

|

|

Education level |

High school or below |

2266 |

0.23 |

1844054 |

0.3833 |

39 |

0.1398 |

31972 |

0.2838 |

18.67 |

|

Some college |

2612 |

0.2651 |

1629688 |

0.3387 |

83 |

0.2975 |

43938 |

0.39 |

||

|

Bachelor and higher |

4975 |

0.5049 |

1337543 |

0.278 |

157 |

0.5627 |

36761 |

0.3263 |

||

|

Housing status |

Own |

7048 |

0.7166 |

3212842 |

0.6689 |

234 |

0.8357 |

94505 |

0.8392 |

59.07*** |

|

Rent |

2239 |

0.2276 |

1289128 |

0.2684 |

32 |

0.1143 |

13721 |

0.1218 |

||

|

Other arrangementsb |

549 |

0.0558 |

301055 |

0.0627 |

14 |

0.05 |

4390 |

0.039 |

||

|

Employment status |

Employed |

5419 |

0.5517 |

2686680 |

0.561 |

140 |

0.5054 |

62075 |

0.5563 |

5.31 |

|

Currently unemployed |

1447 |

0.1473 |

1054892 |

0.2203 |

36 |

0.13 |

20794 |

0.1864 |

||

|

Retired |

2957 |

0.301 |

1047563 |

0.2187 |

101 |

0.3646 |

28711 |

0.2573 |

||

|

Level of income |

Low <25k |

1685 |

0.1903 |

1150837 |

0.2772 |

39 |

0.1523 |

19195 |

0.1888 |

18.55 |

|

Middle 25-50k |

1872 |

0.2114 |

978083 |

0.2356 |

55 |

0.2148 |

23644 |

0.2326 |

||

|

High >50k |

5297 |

0.5983 |

2022439 |

0.4872 |

162 |

0.6328 |

58816 |

0.5786 |

||

|

Health characteristics |

||||||||||

|

Self-rated health (good or better) |

8836 |

0.8955 |

3979748 |

0.8256 |

244 |

0.8746 |

98714 |

0.8757 |

7.77* |

|

|

Number of chronic conditions (c) [0-11] |

-1.4 |

-1.47 |

-1.34 |

-0.02 |

-1.86 |

-1.62 |

-1.74 |

-0.11 |

(3.42**) |

|

|

Depression |

1552 |

0.1573 |

964339 |

0.1998 |

67 |

0.2393 |

26856 |

0.2382 |

4.07 |

|

|

Notes: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. a One drink is equivalent to a 12-ounce beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a drink with one shot of liquor. b “Others” may include group home, staying with friends or family without paying rent. c Chronic conditions include hypertension, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, stroke, asthma, skin cancer, other cancers, COPD, arthritis, kidney disease, diabetes. |

||||||||||

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample by Dementia Caregiving Status.

Multivariate Analyses for Smoking and E-Cigarette Use

Multinomial regression results (Table 2, Model 1) showed that dementia caregivers had a tendency toward higher everyday smoking rates compared to never smokers, though the association was not significant (RRR = 1.94, 95% CI: 0.96, 3.92). Significant predictors of everyday smoking included older age (participants aged 75+ were less likely to smoke every day; RRR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.56; p < 0.001), sex (females were less likely to smoke every day; RRR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.50, 0.76; p < 0.001), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic participants were significantly less likely to smoke every day compared to non-Hispanic Whites; RRR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.24, 0.44; p < 0.001). Higher levels of education and income were associated with lower smoking risks, with participants holding a bachelor’s degree or higher (RRR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.22; p < 0.001) and those with household incomes over $50K (RRR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.39, 0.70; p < 0.001) being less likely to smoke daily. In contrast, more chronic conditions (RRR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.28; p < 0.001) or depression (RRR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.56, 2.53; p < 0.001) were linked to increasing smoking.

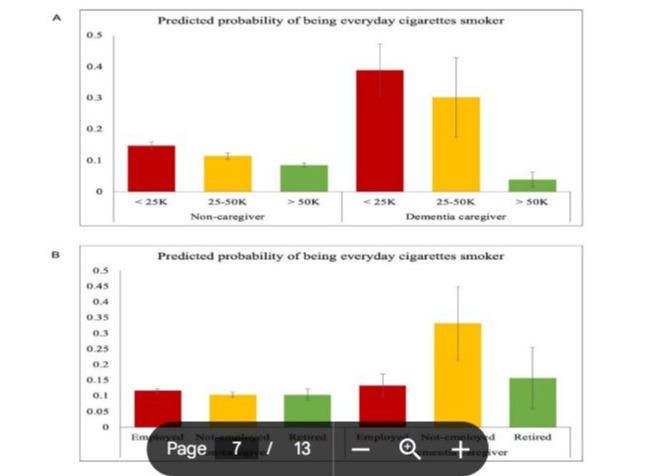

Interaction analyses identified significant effects of income level (being dementia caregiver × low income: RRR=7.03, p=0.001; see Supplementary Table 1) and employment status (being dementia caregiver × not employed/retired: RRR = 4.89, p = 0.03; see Supplementary Table 2). Figures 1A and 1B illustrate that low-income and unemployed dementia caregivers had the highest predicted probability of everyday smoking compared to their non-caregiving counterparts.

For e-cigarette use, multinomial regression results revealed no significant association between dementia caregiving status and everyday e-cigarette use (RRR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.27, 3.13). Most covariates showed similar relationships to those observed in the tobacco smoking models, including age, gender, and depression. Participants living in rented housing were more likely to report everyday e-cigarette use compared to homeowners (RRR = 1.99, 95% CI: 1.22, 3.25; p < 0.01).

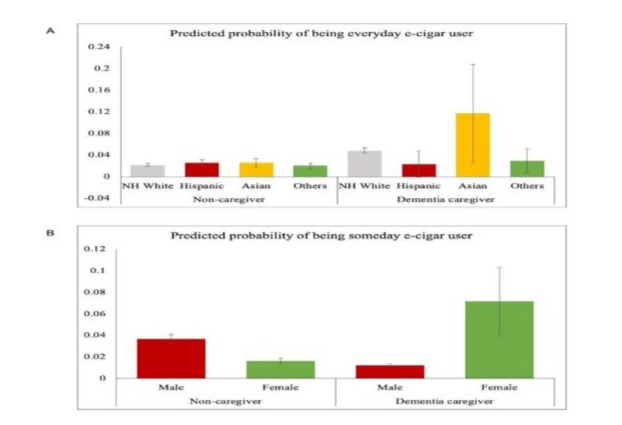

Significant interaction effects were found between dementia caregiving status and race/ethnicity (being dementia caregiver × being Asian: RRR = 5.44, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table 3) and gender (being dementia caregiver × being female: RRR = 1.96, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table 4). Figures 2A and 2B show that Asian dementia caregivers had the highest probability of everyday e-cigarette use, while female caregivers exhibited higher predicted probabilities of someday e-cigarette use than male caregivers.

|

Every day smoker vs. Never Smoker |

Model 1: Tobacco smoking |

Model 2: E-Cigarettes Use |

||

|

RRR |

(95% CI) |

RRR |

(95% CI) |

|

|

Dementia caregiver |

1.94 |

(0.96, 3.92) |

0.92 |

(0.27, 3.11) |

|

Race/Ethnicity (ref. Non-Hispanic White) |

||||

|

Hispanic |

0.33 |

(0.24, 0.44)*** |

1.13 |

(0.64, 2.01) |

|

Asian |

0.63 |

(0.41, 0.94)* |

1.21 |

(0.62, 2.36) |

|

Other |

0.89 |

(0.67, 1.17) |

0.98 |

(0.57, 1.68) |

|

Age |

||||

|

55-64 |

1 |

(0.78, 1.27) |

0.2 |

(0.11, 0.36)*** |

|

65-74 |

0.76 |

(0.56, 1.05) |

0.21 |

(0.10, 0.42)*** |

|

75+ |

0.35 |

(0.22, 0.56)*** |

0.03 |

(0.01, 0.17)*** |

|

Sex (female vs. male) |

0.62 |

(0.50, 0.76)*** |

0.43 |

(0.26, 0.71)** |

|

Married (vs. not married/ coupled) |

0.87 |

(0.69, 1.09) |

0.75 |

(0.47, 1.19) |

|

Education level (ref. High school or below) |

||||

|

Some college or associate degree |

0.67 |

(0.53, 0.85) ** |

1.12 |

(0.69, 1.81) |

|

Bachelor’s degree or above |

0.17 |

(0.13, 0.22)*** |

0.33 |

(0.17, 0.61)** |

|

House ownership (ref. Owned) |

||||

|

Rent |

1.12 |

(0.87, 1.43) |

1.99 |

(1.22, 3.52)** |

|

Other |

0.62 |

(0.41, 0.93)* |

1.99 |

(0.92, 4.30) |

|

Employment status (ref. Employed) |

||||

|

Not employed |

0.86 |

(0.67, 1.11) |

0.87 |

(0.48, 1.56) |

|

Retired |

0.92 |

(0.59, 1.42) |

0.75 |

(0.30, 1.89) |

|

Annual household income (ref. < 25K USD) |

||||

|

25-50K |

0.75 |

(0.57, 1.00) |

0.93 |

(0.48, 1.82) |

|

> 50K |

0.52 |

(0.39, 0.70)*** |

1.85 |

(0.99, 3.47) |

|

Self-rated health (good vs. not good) |

0.81 |

(0.61, 1.07) |

1.05 |

(0.56, 1.97) |

|

Number of chronic conditions [0-11] |

1.17 |

(1.08, 1.28)*** |

1.09 |

(0.87, 1.38) |

|

Depression (yes vs. no) |

1.99 |

(1.56, 2.53)*** |

2.84 |

(1.74, 4.36)*** |

Note: The regression models do not include African American participants due to a lack of representativeness in the dementia caregiver subsample.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 2: Multinomial Regression Models for Tobacco Smoking and E-Cigarettes Use

Figure 1: Predicted probability of being an everyday cigarette smoker by income and employment status.

Description: This figure shows the predicted probability of being an everyday cigarette smoker among dementia caregivers and noncaregivers, stratified by (A) annual household income levels and (B) employment status. The results indicate that low-income and unemployed dementia caregivers are at higher risk for daily smoking.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of being an everyday or someday e-cigarette user by race/ethnicity and gender.

Description: This figure illustrates the predicted probability of being an everyday or someday e-cigarette user among dementia caregivers and non-caregivers, stratified by (A) race/ethnicity and (B) gender. The findings indicate that Asian and female dementia caregivers have a significantly higher likelihood of e-cigarette use.

Multivariate Analyses for Alcohol Consumption

ZINB regression models (Table 3) found no significant association between dementia caregiving status and the number of drinking days (IRR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.70, 1.16) or the number of drinks per drinking day (IRR = 1.29, 95% CI: 0.87, 1.91). However, several covariates showed notable associations. Women drank on fewer days (IRR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.67, 0.79; p < 0.001), and consumed fewer drinks per day (IRR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.61, 0.74; p < 0.001). Being in older age groups (55-64, 65-74, and 75+) drank more frequently (e.g., IRR = 1.56 for age 75+; p < 0.001), but consumed fewer drinks per day (e.g., IRR = 0.60 for age 75+; p < 0.001). Participants living in rented or other non-owned housing arrangements reported higher drinking intensity compared to homeowners (e.g., IRR = 1.26 for renters; p < 0.001).

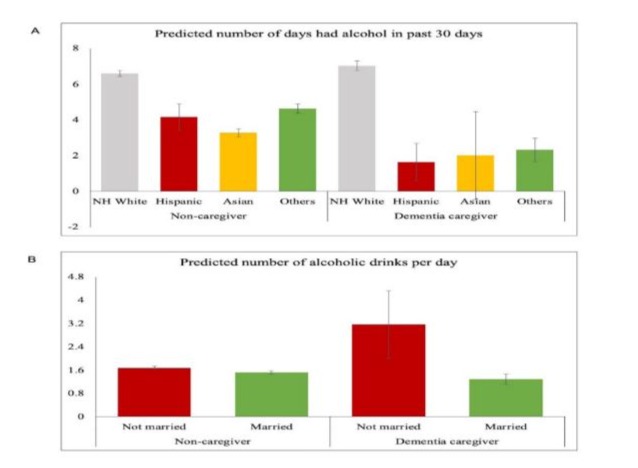

Interaction analyses identified significant effects between dementia caregiving and race/ethnicity for drinking days (being dementia caregiver × being Hispanic: IRR = 0.37, p = 0.02; see Supplementary Table 5) and between dementia caregiving and marital status for the number of drinks per day (being dementia caregiver × being not married: IRR = 2.23, p = 0.04; see Supplementary Table 6). Figure 3A shows that Hispanic dementia caregivers reported fewer drinking days than their non-caregiver counterparts, while Whites showed no difference. Figure 3B illustrates that unmarried dementia caregivers consumed significantly more drinks per day than both married caregivers and non-caregivers across marital statuses.

|

Model 3: Number of days had alcohol in past 30 days |

Model 4: Number of drinks per drinking day |

|||

|

IRR |

(95% CI) |

IRR |

(95% CI) |

|

|

Dementia caregiver |

0.9 |

(0.70, 1.16) |

1.29 |

(0.87, 1.91) |

|

Race/Ethnicity (ref. Non-Hispanic White) |

||||

|

Hispanic |

0.68 |

(0.60, 0.77)*** |

1.19 |

(1.01, 1.41)* |

|

Asian |

0.64 |

(0.55, 0.75)*** |

0.93 |

(0.76, 1.13) |

|

Other |

0.78 |

(0.69, 0.88)*** |

1.32 |

(1.14, 1.52)*** |

|

Age |

||||

|

55-64 |

1.26 |

(1.14, 1.38)*** |

0.81 |

(0.73, 0.91)*** |

|

65-74 |

1.39 |

(1.24, 1.57)*** |

0.7 |

(0.62, 0.79)*** |

|

75+ |

1.56 |

(1.34, 1.80)*** |

0.6 |

(0.50, 0.72)*** |

|

Sex (female vs. male) |

0.73 |

(0.67, 0.79)*** |

0.67 |

(0.61, 0.74)*** |

|

Married (vs. not married/coupled) |

1 |

(0.91, 1.10) |

0.89 |

(0.80, 0.99)* |

|

Education level (ref. High school or below) |

||||

|

Some college or associate degree |

0.92 |

(0.82, 1.02) |

0.81 |

(0.72, 0.91)** |

|

Bachelor’s degree or above |

1.03 |

(0.93, 1.13) |

0.73 |

(0.64, 0.83)*** |

|

House ownership (ref. Owned) |

||||

|

Rent |

0.97 |

(0.88, 1.08) |

1.26 |

(1.10, 1.46)** |

|

Other |

0.94 |

(0.77, 1.18) |

1.33 |

(1.05, 1.68)* |

|

Employment status (ref. Employed) |

||||

|

Not employed |

0.95 |

(0.84, 1.07) |

0.99 |

(0.84, 1.17) |

|

Retired |

1.17 |

(0.98, 1.39) |

0.92 |

(0.79, 1.07) |

|

Annual household income (ref. < 25K USD) |

||||

|

25-50K |

1 |

(0.87, 1.16) |

0.98 |

(0.83, 1.16) |

|

> 50K |

1.22 |

(1.06, 1.41)** |

1.1 |

(0.92, 1.32) |

|

Self-rated health (good vs. not good) |

1.04 |

(0.89, 1.20) |

0.9 |

(0.75, 1.07) |

|

Number of chronic conditions [0-11] |

0.97 |

(0.93, 1.02) |

0.98 |

(0.94, 1.02) |

|

Depression (yes vs. no) |

0.99 |

(0.90, 1.10) |

0.99 |

(0.89, 1.11) |

Note: The regression models do not include African American participants due to a lack of representativeness in the dementia caregiver subsample.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 3: Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Regression Models for Alcohol Consumption.

Figure 3: Alcohol consumption patterns among dementia caregivers and non-caregivers.

Description: This figure presents the association between alcohol consumption and dementia caregiving status, stratified by (A) racial/ethnic identity and (B) marital status. The results highlight that racial/ethnic minority dementia caregivers drink fewer days per month, while unmarried dementia caregivers consume more alcohol per drinking day.

Discussion

This study examined differences in tobacco smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption between dementia caregivers and non-caregivers, as well as the sociodemographic and health-related factors influencing these behaviors. Dementia caregivers exhibited similar rates of these behaviors overall. Significant correlates of smoking and alcohol consumption included younger age, being male, lower education, lower income, more chronic conditions, and a history of depression. Interaction analyses identified vulnerable subgroups, with low-income and unemployed dementia caregivers more likely to smoke daily and unmarried caregivers consuming more alcohol per drinking day. Although females and Asians showed similar or even lower prevalence of e-cigarette use among non-caregivers, being dementia caregivers significantly increased their probability of using e-cigarettes. These findings address gaps in research by highlighting risk variations among caregivers. They underscore the need for tailored interventions and policies to support dementia caregivers, particularly those in socioeconomically and culturally vulnerable populations.

Similar Patterns of Unhealthy Behaviors between Dementia Caregivers and Non-Caregivers

The first objective of this study was to compare dementia caregivers and non-caregivers regarding smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol use. Results showed no statistically significant differences, despite slightly higher daily smoking rates among dementia caregivers. This lack of significant differences may be explained by the multifaceted nature of stressors experienced by both caregivers and non-caregivers, such as financial strain, health challenges, or other social determinants of health, which can also influence unhealthy coping behaviors [8,9]. This was further supported by the observed associations of low education, low income, and a history of depression with smoking and alcohol drinking. Furthermore, the Stress and Coping Model also suggests that caregiving stress alone may not always manifest in negative health behaviors, as coping strategies depend on available resources, perceived control, and external support systems [30].

The Various Patterns of Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use among Dementia Caregivers

Despite no significant difference in tobacco smoking between dementia caregivers and non-caregivers, several factors were associated with higher tobacco use, including younger age, lower education, lower income, more chronic conditions, and a history of depression. These findings align with prior research linking socioeconomic disadvantage and mental health challenges to increased smoking prevalence [31]. Notably, interaction analyses revealed that low income and unemployed dementia caregivers were significantly more likely to smoke daily compared to their non-caregiver counterparts. These interactions may reflect compounded stressors, as financial and occupational instability can limit access to resources and support systems, potentially intensifying reliance on smoking as a coping mechanism [32]. These findings highlight the importance of targeted interventions to reduce smoking among caregivers, particularly for those facing financial or occupational vulnerabilities, to improve their health outcomes and caregiving capacity.

Overall, e-cigarette use was lower than tobacco smoking, regardless of dementia caregiving status. Similar to tobacco smoking, significant predictors included being male, having lower education, not owning a home, and a history of depression. This suggests that the impact of socioeconomic vulnerabilities and mental health problems on traditional substance use may also extend to e-cigarette use. Given the 0.8% average annual increase in adult e-cigarette use, interventions are needed to prevent reliance on e-cigarette related unhealthy coping mechanisms [17]. Unlike tobacco smoking, younger adults (below 55 years) were more likely to use e-cigarette, consistent with trends showing younger populations adopting e-cigarettes due to perceptions of reduced harm [33].

Notably, female and Asian dementia caregivers exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of e-cigarette use compared to their non-caregiver counterparts. Potential explanations might include stress, cultural expectations, health beliefs, and marketing influences. Female caregivers often experience higher stress due to social and cultural expectations of caregiving roles, leading to increased needs for coping strategies [34]. Women’s generally lower use of traditional tobacco may drive them to choose e-cigarettes as a perceived healthier alternative [33]. Similar for Asian caregivers, cultural values such as familism and filial piety intersect with social norms discouraging tobacco use, making e-cigarettes a more socially acceptable option [21]. Additionally, marketing strategies increasingly target diverse populations, using culturally resonant messages that frame e-cigarettes as modern, safer alternatives to traditional smoking [35]. These findings underscore the need to pay closer attention to e-cigarette use and its potential health impacts among caregivers, while tailoring support and intervention strategies to meet the specific needs of different gender and cultural groups.

Frequency and Intensity of Alcohol Use among Dementia Caregivers

Dementia caregivers and non-caregivers reported similar alcohol consumption patterns, with caregivers drinking slightly fewer days, but caregiving status was not a significant predictor in regression models. This may be due to caregiving burden limiting opportunities for social or leisure drinking [24]. Interaction analyses revealed no differences in drinking frequency among White caregivers, but racial/ethnic minority caregivers, including Hispanic, Asian, and other groups, reported significantly fewer drinking days when they were dementia caregivers. This disparity may reflect socioeconomic and cultural differences, as higherincome White individuals tend to drink more frequently, due to greater access to alcohol, more leisure time, and broader social and recreational activities [36]. These findings underscore the importance of considering racial, cultural, and socioeconomic contexts when examining alcohol use patterns among dementia caregivers.

Fewer drinking days do not necessarily indicate lower health risks, as heavy drinking is more common among individuals with limited socioeconomic resources, leading to greater negative health outcomes [37]. The findings revealed that being Hispanic, unmarried, having only a high school diploma, and renting a home were associated with consuming more drinks per drinking day, highlighting the role of socioeconomic and demographic vulnerabilities. Cultural norms and coping strategies may partly explain these patterns, as some individuals in these groups may turn to alcohol as a way to manage stress or compensate for limited social and financial resources [13,15]. Being married significantly reduced the number of drinks per day among dementia caregivers, emphasizing the protective role of social support from intimate relationships in mitigating unhealthy behaviors [38].

Study Implications

The findings of this study have important implications for theory, practice, and policy. Maladaptive coping behaviors, including smoking and alcohol use, are influenced not only by caregiving stress but also by access to coping resources and societal pressures [11,7]. This study extends these insights to e-cigarette use. The interaction between caregiving stress and socioeconomic and demographic factors underscores the need for subgroup-specific interventions, particularly for socioeconomically vulnerable populations. Targeted interventions such as support groups, educational programs, and caregiver resources should prioritize low-income, female, and minority caregivers while improving health literacy on smoking and alcohol use. While e-cigarettes may serve as a harm-reduction alternative to traditional tobacco [21], excessive use and its potential health risks warrant closer attention. Stricter regulations and awareness campaigns are needed, especially for populations perceiving e-cigarettes as lowrisk. Alcohol-related interventions should focus on heavy drinking among dementia caregivers by promoting stress management and promoting healthier coping strategies.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several notable strengths. First, it uses a large, representative dataset from the 2017 BRFSS, allowing for generalizable insights into a diverse population while examining multifaceted behavioral outcomes, including tobacco smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption. Second, the exploratory interaction analyses highlight at-risk subgroups of dementia caregivers, providing a nuanced understanding of how sociodemographic and caregiving status intersect to influence unhealthy behaviors. Lastly, the inclusion of e-cigarette use contributes novel insights into an emerging public health concern, particularly among dementia caregivers.

Despite its strengths, this study also has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences about the relationships between dementia caregiving, sociodemographic factors, and unhealthy behaviors. Second, the findings may have limited generalizability, as the analysis includes only five states, a relatively small sample of dementia caregivers, and low representation of African American. Third, caregiving stress was not fully captured, as caregiving intensity, tasks, and perceived burden were not examined. Future research should explore how these caregiving factors interact with psychosocial resilience and influence unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and health outcomes.

Conclusions

This study examines patterns and predictors of tobacco smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol consumption among dementia caregivers and non-caregivers. While overall differences were not significant, the findings underscore the influence of socioeconomic vulnerabilities, demographic characteristics, and caregiving stress on unhealthy coping behaviors. Subgroup analyses revealed that low-income and unemployed dementia caregivers had higher smoking rates, while female and Asian caregivers exhibit higher e-cigarette use, and unmarried caregivers are more likely to engage in heavy drinking. These results highlight the critical need for tailored interventions addressing the unique stressors and needs of dementia caregivers, particularly for vulnerable groups. Public health initiatives should prioritize caregiver support programs, smoking cessation, and alcohol reduction strategies, while addressing emerging risks of e-cigarette use. Further research should examine caregiving intensity, perceived burden, and resilience factors to better understand their impact on caregiver coping capacities and develop strategies to improve both caregiver well-being and the quality of care.

Conflict of Interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability: The study used publicly available data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, which can be accessed at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/

Author Contributions: Jiaming Liang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writingoriginal draft. Maria P. Aranda: conceptualization, writing-review and editing.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association (2022) 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 18: 700-789.

- Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL (2015) The Disproportionate Impact Of Dementia On Family And Unpaid Caregiving To Older Adults. Health Affairs. 34: 1642-1649.

- Liang J, Aranda MP, Jang Y, Wilber K (2023) The Role of Social Isolation on Mediating Depression and Anxiety among Primary Family Caregivers of Older Adults: A Two-Wave Mediation Analysis. Int J Behav Med 31: 445-458.

- Ross A, Shamburek R, Wehrlen L, Klagholz SD, Yang L, et al. (2017) Cardiometabolic risk factors and health behaviors in family caregivers. PLoS One 12: e0176408.

- Wilson SJ, Padin AC, Birmingham DJ, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK (2018) When Distress Becomes Somatic: Dementia Family Caregivers’ Distress and Genetic Vulnerability to Pain and Sleep Problems. The Gerontologist. 59: e451-e460.

- Hui SA, Elliott TR, Martin R, Uswatte G (2011) Family caregivers’ attributions about care-recipient behaviour: Does caregiver relationship satisfaction mediate the attribution-distress relationship? British Journal of Health Psychology. 16: 642-659.

- Lazarus RS (1993) Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present, and Future. Psychosom Med 55: 234-247.

- Halinski M, Duxbury L, Stevenson M (2019) Employed Caregivers’ Response to Family-Role Overload: the Role of Control-at-Home and Caregiver Type. Journal of Business and Psychology. 35: 99-115.

- Lloyd J, Muers J, Patterson TG, Marczak M (2018) Self-Compassion, Coping Strategies, and Caregiver Burden in Caregivers of People with Dementia. Clinical Gerontologist. 42: 47-59.

- Gaugler JE, Eppinger A, King J, Sandberg T, Regine WF (2013) Coping and its effects on cancer caregiving. Support Care Cancer 21: 385-395.

- Han Y, Hu D, Liu Y, Lu C, Luo Z, et al. (2014) Coping styles and social support among depressed Chinese family caregivers of patients with esophageal cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 18: 571577.

- Rao P, Grover S, Chakrabarti S (2020) Coping with caregiving stress among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 54: 102219.

- Gottschalk S, König H-H, Brettschneider C (2020) The association between informal caregiving and behavioral risk factors: a crosssectional study. Int J Public Health 65: 911-921.

- Ross A, Sundaramurthi T, Bevans M (2013) A Labor of Love: The Influence of Cancer Caregiving on Health Behaviors. Cancer Nurs 36: 474-483.

- Hernandez CJA, Browning WR, Yildiz M, Sullivan TP, Pickering CE (2024) Emotion Regulation, Coping Strategies, and Hazardous Drinking Among Family Caregivers of People with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 17: 81-90.

- Secinti E (2021) Relation between perceived injustice and distress in cancer: meaning making and acceptance of cancer as mediators (thesis). Purdue University Graduate School.

- CDC (2024a) E-Cigarette Use Among Adults [WWW Document]. Smoking and Tobacco Use.

- Li X, Yuan L, Wang F (2024) Health outcomes of electronic cigarettes. Chinese Medical Journal. 137: 1903.

- St. Helen G, Eaton DL (2018) Public Health Consequences of e-Cigarette Use. JAMA Internal Medicine 178: 984-986.

- Vardavas CI, Anagnostopoulos N, Kougias M, Evangelopoulou V, Connolly GN, et al. (2012) Short-term Pulmonary Effects of Using an Electronic Cigarette: Impact on Respiratory Flow Resistance, Impedance, and Exhaled Nitric Oxide. CHEST 141: 1400-1406.

- Cummins SE, Zhu S-H, Tedeschi GJ, Gamst AC, Myers MG (2014) Use of e-cigarettes by individuals with mental health conditions. Tobacco Control. 23: iii48-iii53.

- Gomes GA, de O, Luchesi BM, Gratão ACM, Orlandi F, et al. (2019) Prevalence of Physical Inactivity and Associated Factors Among Older Caregivers of Older Adults. J Aging Health 31: 793-813.

- Uemura MY, Hirakawa Y (2020) Self-Perceived Eating Habits among Family Caregivers of Older People with Dementia: A Qualitative Study. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 39: 205-213.

- Kunicki Z, Jones R (2020) Prevalence of Heavy Alcohol Use by Caregivers of Persons With Alzheimer’s Disease or Related Dementia. Innov Aging 4: 359.

- CDC (2024b) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [WWW Document].

- Langkamp DL, Lehman A, Lemeshow S (2010) Techniques for Handling Missing Data in Secondary Analyses of Large Surveys. Academic paediatrics. 10: 205-210.

- Kindratt TB, Sylvers DL, Yoshikawa A, López-Anuarbe M, Webster NJ, et al. (2023) Dementia Caregiving Experiences and Health Across Geographic Contexts by Race and Ethnicity. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 78: S48-S58.

- StataCorp LLC (2023) Stata: Statistical Software Release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Chen X, D’Souza V, Yu L (2019) The oral health status of residents with different cognitive and dental-related functions in three North Carolina assisted living facilities. Gerodontology. 36: 142-148.

- Gottlieb BH, Wolfe J (2002) Coping with family caregiving to persons with dementia: A critical review. Aging & Mental Health 6: 325-342.

- Dhana K, Agarwal P, James BD, Leurgans SE, Rajan KB, et al. (2024) Healthy Lifestyle and Cognition in Older Adults with Common Neuropathologies of Dementia. JAMA Neurology.

- Otuyama LJ, Oliveira D, Locatelli D, Machado D de A, Noto AR, et al. (2020) Tobacco smoking and risk for dementia: evidence from the 10/66 population-based longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health. 24: 1796-1806.

- Baeza-Loya S, Viswanath H, Carter A, Molfese DL, Velasquez KM, et al. (2014) Perceptions about e-cigarette safety may lead to e-smoking during pregnancy. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 78: 243-252.

- Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S (2016) Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World journal of psychiatry. 6: 7-17.

- Vassey J, Valente T, Barker J, Stanton C, Li D, et al. (2023) E-cigarette brands and social media influencers on Instagram: a social network analysis. Tobacco Control. 32: e184-e191.

- Patterson SE, Tate AM, Hu Y-L, Wang JJ, Schoeni RF, et al. (2022) The Social Cost of Providing Care to Older Adults with and without Dementia. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 78: S71–S80.

- Rehm J, Hasan OSM, Black SE, Shield KD, Schwarzinger M (2019) Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alzheimers Res Ther 11: 1.

- Curl A, Bulanda J, Roberts AR (2021) Marital Quality and Heavy Alcohol Use Among Older Couples. Innovation in Aging. 5: 404.

- CDC (2022) 2017 BRFSS Survey Data and Documentation [WWW Document].

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.