The Deslarzes-Voûte Homemade Laparoscopic Simulator: Adjustable Camera for an Innovate Laparoscopy Training

by Jeanne Voute1*, David Fuks1, Philip Deslarzes1

1Department of Visceral Surgery, Lausanne University Hospital CHUV, University of Lausanne (UNIL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

*Corresponding Author: Deslarzes Philip, Department of Visceral Surgery, Lausanne University Hospital CHUV, University of Lausanne (UNIL), 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

Received Date: 27 November 2025

Accepted Date: 01 December 2025

Published Date: 04 December 2025

Citation: Voute J, Fuks D, Deslarzes P. (2025). The Deslarzes-Voûte Homemade Laparoscopic Simulator: Adjustable Camera for an Innovate Laparoscopy Training. Ann Case Report. 10: 2460. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102460

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic skill acquisition is essential yet hindered by the high cost of commercial simulators. Existing low-cost models often lack the dynamic visual perspectives crucial for comprehensive training.

Objective: To design and validate a sustainable, low-cost laparoscopic simulator featuring an innovative adjustable camera system.

Methods: The "VD-60 Lap-Box" was constructed from recyclable spruce wood for approximately 60 CHF. Its key feature is a camera mounted on interior Velcro, allowing easy repositioning to simulate various surgical views, including challenging angles. Fifteen surgical residents performed standardized tasks and rated the simulator on a 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire assessing realism, ergonomics, and utility.

Results: The simulator achieved high user satisfaction, with an overall score of 4.26/5, surpassing the 80% benchmark for satisfactory training tools. Participants highly rated the realism of instrument handling (4.3/5) and found the exercises exceptionally useful for skill development (4.5/5).

Conclusion: The VD-60 Lap-Box effectively bridges a gap in surgical simulation by offering an affordable, eco-friendly, and pedagogically effective trainer. Its unique adjustable camera system provides a versatile training experience, making it a valuable tool for enhancing laparoscopic training, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Keywords: Simulator; Training; Minimal Invasive Surgery; Residency; Learning Curve.

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery has become the gold standard for many surgical procedures. Due to its minimally invasive nature, laparoscopic approach offers significant benefits, including reduced blood loss, shorter hospital stays, less postoperative pain, improved cosmetic outcomes, and faster patient recovery. However, mastering this technique presents distinct challenges:

operating with two-dimensional visualization, refining handeye coordination, and maneuvering instruments with restricted mobility due to fixed entry points. These factors contribute to a steep and variable learning curve, underscoring the importance of structured training in medical education [1].

Simulation-based training provides a safe and controlled setting for skill development [2,3]. Various simulation methods exist, including virtual reality systems, animal/cadaver models, and box trainers. Among these, box trainers have proven particularly effective for acquiring fundamental laparoscopic skills, improving operative efficiency, and they are more easily available [4,5]. Despite their benefits, access to commercial trainers remains limited, especially in resource-constrained regions. As a result, affordable, homemade alternatives could play a crucial role in bridging this gap [6,7].

Since Sackier et al. introduced the first laparoscopic simulator in 1991; numerous studies have explored different designs [8]. A review by Li et al compared commercial and non-commercial simulators, highlighting that while many models are cost-effective and easy to assemble, they often lack detailed cost analysis and standardized validation [9]. Despite subsequent advancements in simulator design, a comprehensive guide does not exist for constructing a validated homemade laparoscopic trainer.

This study addresses that gap by presenting (VD-60 Lap-Box), a low-cost, realistic laparoscopic box trainer with full build instructions and bill of materials. To assess its effectiveness, 15 surgical residents evaluated the simulator.

Methods

The box

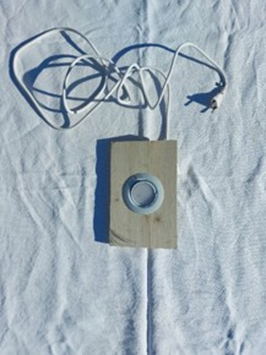

Spruce was used for the construction of the box, as this wood can withstand a drill. Four wooden plates measuring 400mmx150mmx18mm, four wooden plates measuring 240mmx150mmx18mm and two wooden plates measuring 400mmx276mx3mm were used. One hole was made using a power drill with a wood drill to bore a hole of 78mm in the middle of a 240m x150mmx18mm plate to install the light source (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Light source outside the box

In this setup, we used a circular spotlight originally designed for outdoor environments, such as garden lighting, as the light source.

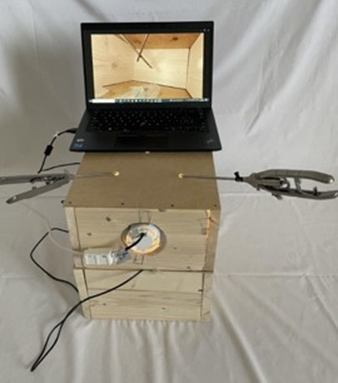

Using the plates and 23mm-long nails, two parallelepipeds were built. These two parallelepipeds were placed one on top of the other using two articulated metal plates screwed into the wood with 18mm long screws so that the simulator could be opened easily (Figure 2). Five holes of 1cm in diameter were then drilled in the top plate to allow the instruments to be inserted (Figure 3).

Figure 2: The box with two articulated metal plates

Figure 3: The box with the central hole allowing the insertion of the light source. Above the box: the camera, the light source, and the instrument

Velcro, to which the webcam can be attached, was placed in different parts of the top parallelepipeds. The camera used is a standard webcam, readily available in most appliance or computer stores. Nowadays, it is possible to use the camera of a cell phone and an application linking it to the computer via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. The final size of the box was 16 liters (Figure 4 and 5). The laparoscopic forceps and needle holder were provided free of charge by the hospital after being considered too worn for clinical use in the operating room.

Figure 4: Side view of the 16 liters laparoscopic box

Figure 5: Front view of the 16 liters laparoscopic box

Participants and evaluation

Fifteen surgical residents from the Department of Surgery participated in the evaluation of the VD-60 Lap-Box.

Each resident performed a series of standardized Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS)-style tasks on the trainer, including peg transfer, precision cutting, and intracorporeal knot tying, based on a video.

Upon completion of the training session, participants completed a five-item light questionnaire designed to assess the simulator’s realism and usability. Each question was rated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree):

- The simulator realistically reproduces laparoscopic surgical conditions.

- The ergonomics (instrument position, access, and visibility) are satisfactory.

- The illumination is adequate and realistic.

- The handling of instruments is similar to that in the operating room.

- The exercises are useful for developing laparoscopic skills.

Responses were analysed to determine face validity, with mean scores and standard deviations calculated for each question. According to the literature, a simulator is considered satisfactory when at least 80% of participants’ responses score 4 or higher on a 5-point Likert scale.

Reference video for evaluation

To guide the residents in performing the exercises on the VD60 Lap-Box, a demonstration video was created under the same conditions as the simulator. The video presents a peg transfer exercise to develop precision and hand–eye coordination, followed by suturing two strips to improve dexterity in needle and thread handling. Finally, it includes placing a needle on a banana, simulating delicate maneuvers on soft tissue. Residents used this video as a reference to perform the exercises and to assess the realism and ergonomics of the simulator.

Results

The total material cost for constructing the VD-60 Lap-Box was 60 CHF (approximately 60 EUR), with a detailed breakdown provided in (Table 1). The primary innovation of this simulator is its dynamic camera system. By utilizing strategically placed Velcro strips on the interior of the box, the webcam can be easily repositioned, allowing trainees to practice from multiple viewpoints. This includes challenging perspectives, such as having the camera directly in front of the operator, which simulates difficult intraoperative visual conditions. The internal dimensions of the 16-liter box were designed to ergonomically mimic the human abdomen, providing a realistic spatial environment for training. Furthermore, the construction from spruce wood offers the dual advantage of customizability for different surgical specialties and environmental sustainability, as the materials are largely recyclable.

|

Material / Component |

Quantity |

Unit Cost (CHF) |

Total Cost (CHF) |

Notes |

|

Spruce wooden plates 40×15×0.18 cm |

4 |

3 |

12 |

Main box walls |

|

Spruce wooden plates 24×15×0.18 cm |

4 |

2.5 |

10 |

Top/bottom panels |

|

Spruce wooden plates 40×27.6×0.03 cm |

2 |

3 |

6 |

Thin panel for inside lining |

|

Nails 23 mm |

50 |

0.05 |

2.5 |

Box assembly |

|

Screws 18 mm |

20 |

0.1 |

2 |

Hinges installation |

|

Metal articulated plates |

2 |

5 |

10 |

Box hinge for opening |

|

Velcro strips |

2 m |

3 |

6 |

Camera attachment |

|

Spotlight (circular, outdoor) |

1 |

5 |

5 |

Light source |

|

Webcam (standard) |

1 |

6 |

6 |

Camera for visualization |

|

Total |

- |

- |

60 |

Table 1: Total material cost

To quantitatively assess the simulator's face validity, 15 surgical residents completed a post-training questionnaire. The results, summarized in (Table 2), demonstrated high levels of satisfaction across all domains. The simulator’s ability to reproduce laparoscopic conditions received a mean score of 4.1/5. Ergonomic design and realistic illumination were both rated 4.2/5. Instrument handling, a critical factor for skill transfer, scored 4.3/5, indicating that the tactile feedback and maneuverability were comparable to the operating room. Most notably, the relevance of the training exercises for skill development achieved the highest mean score of 4.5/5. The overall mean satisfaction score was 4.26/5, corresponding to an 85% satisfaction rate, which surpasses the 80% benchmark commonly used in the literature to define a satisfactory training tool.

|

Question |

Mean Score (1-5) |

Standard Deviation |

% Scoring ≥4 |

|

1. Realistically reproduces conditions |

4.1 |

+/- 0.8 |

73% |

|

2. Satisfactory ergonomics |

4.2 |

+/- 0.7 |

80% |

|

3. Adequate and realistic illumination |

4.2 |

+/- 0.6 |

93% |

|

4. Realistic instrument handling |

4.3 |

+/- 0.7 |

87% |

|

5. Usefulness of exercises |

4.5 |

+/- 0.6 |

93% |

|

Overall Satisfaction |

4.26 |

85% |

Table 2: overall satisfaction according to five-point Lickert scale

Discussion

This study successfully describes the construction and initial validation of the VD-60 Lap-Box, a low-cost, homemade laparoscopic simulator. Our findings confirm that it is possible to create an effective training tool for approximately 60 CHF, which aligns with the goal of increasing accessibility as outlined in prior reviews of low-cost simulators [9]. The overwhelmingly positive feedback from surgical residents, with an overall satisfaction rate of 85%, provides strong evidence for its face validity and potential for widespread adoption in surgical training programs, particularly those with limited resources.

The most significant innovation of the VD-60 Lap-Box is its adjustable camera system. While numerous homemade simulators have been described in the literature, the majority feature fixed trocar positions for the camera, limiting the range of visual perspectives a trainee can experience [6, 9]. Our design, using a simple Velcro attachment, directly addresses this limitation. It allows for the simulation of complex and suboptimal visual scenarios, such as an "opposing-view" camera angle, which is a common challenge in real surgery

but rarely trained on with basic simulators. This modularity enhances its fidelity without adding cost or complexity, a feature not thoroughly explored in previous studies. For instance, while Li et al. cataloged various designs, they noted a general lack of such adaptable features in low-cost models [9].

In terms of cost-effectiveness, our simulator presents a compelling alternative. Franklin et al. demonstrated that low-cost equipment could effectively replace standard FLS trainers without compromising educational outcomes [7]. The VD-60 Lap-Box builds upon this principle, offering a complete physical trainer at a fraction of the cost of commercial box trainers or virtual reality systems. Furthermore, our use of recyclable spruce wood introduces an element of sustainability often overlooked in simulator design. This contrasts with many commercial products and some do it yourself models that rely on plastics or non-recyclable composites, addressing a growing concern for environmental impact in medical education.

When compared to the historical progression of box trainers, from Sackier's initial design [8] to the modern fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery system, our simulator demonstrates that key pedagogical principles-realistic instrument handling, adequate workspace, and task-specific training—can be preserved at minimal cost [8]. The high score (4.5/5) for exercise usefulness indicates that the fundamental skills practiced on our simulator are perceived as directly transferable to the operating room, which is the ultimate goal of simulation-based training [1, 4].

This study has limitations. The sample size for validation, while consistent with similar pilot studies, is relatively small. The evaluation was also limited to face validity; future studies should assess construct validity (its ability to distinguish between novice and expert surgeons) and concurrent validity (by correlating performance on the VD-60 with performance on established FLS platforms). Longitudinal studies tracking skill retention and transfer to the operating room would provide the most robust evidence of its efficacy.

Conclusion

The VD-60 Lap-Box represents a significant step forward in the domain of low-fidelity surgical simulation. It is not merely a cost-effective alternative but an innovative one, offering unique features like an adjustable camera that enhance its training value. By providing detailed construction guidelines and demonstrating strong user satisfaction, this simulator is poised to become a valuable tool for democratizing laparoscopic training, especially in resource-limited settings and for early-stage surgical residents.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank the residents who participated in the study by using the VD-60 laparoscopic simulator and completing the evaluation questionnaires. Their time, feedback, and engagement were essential to assess the educational value and practicality of the device.

Authorship confirmation/contribution statement: All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Jeanne Voûte and Philip Deslarzes designed and built the VD-60 simulator. David Fuks and Philip Deslarzes coordinated the study and data acquisition. Jeanne Voûte and Maria Conticchio performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Author’s disclosure: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Funding statement: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Statement: will not be publicly available since part of an institutional quality improvement project.

Conflict of interest: None to declare related to this study

Declaration of AI using: None using of AI.

All others: None to declare.

References

- Singh P, Aggarwal R, Tahir M, Pucher PH, Darzi A. (2007). Training improves laparoscopic technical skill: A randomized controlled study. British Journal of Surgery. 94: 322-326.

- Dubuisson J, Vilmin F, Boulvain M, Combescure C, Petignat P, et al. (2016). Do laparoscopic pelvic trainer exercises improve residents’ surgical skills? A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 206: 177-180.

- Okhunov Z, Okeke Z, Smith AD. (2012). The role of laparoscopy training in urology. The Training Courses of Urological Laparoscopy. London: Springer. 1-9.

- Zendejas B, Brydges R, Hamstra SJ, Cook DA. (2013). State of the evidence on simulation-based training for laparoscopic surgery: A systematic review. Annals of Surgery. 257: 586-593.

- Torkington J, Smith SG, Rees BI, Darzi A. (2000). The role of simulation in surgical training. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 82: 88-94.

- Shaharan S, Neary P. (2014). Evaluation of surgical training in the era of simulation. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 6: 436447.

- Franklin BR, Placek SB, Wagner MD, Haviland SM, O'Donnell MT, et al. (2017). Cost comparison of fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery training completed with standard fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery equipment versus low-cost equipment. Journal of Surgical Education. 74: 459-465.

- Sackier JM, Berci G, Paz-Partlow M. (1991). A new training device for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgical Endoscopy. 5: 158-159.

- Li MM, George J. (2017). A systematic review of low-cost laparoscopic simulators. Surgical Endoscopy. 31: 38-48.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.