Obesity and Cancer: Inventory of Knowledge Gaps and Communication Requirements within (Preventive) Oncology

by Vrolijk EEM1, Althuis NM1, Rooker K1, Argalaless AAAA1 Vonken L2, Hoge CV3, Moossdorff M4, Kremer S5, Engelen SME4 , Werner HMJ,1,6*

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht, The Netherlands

2Department of Health Promotion, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI) Maastricht University. Maastricht, The Netherlands

3Department of Gastroenterology and liver disorders, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht, The Netherlands

4Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht, The Netherlands

5Department of Health Promotion, Institute of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism (NUTRIM). Maastricht University Medical Center+, HX Maastricht, The Netherlands

6GROW-Research institute for oncology and reproduction, Maastricht University Medical Center+, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Received Date: 22 December 2025

Accepted Date: 29 December 2025

Published Date: 31 December 2025

Citation: Vrolijk EEM, Althuis NM, Rooker K, Argalaless AAAA, Vonken L, et al (2025) Obesity and Cancer: Inventory of Knowledge Gaps and Communication Requirements within (Preventive) Oncology. Advs Prev Med Health Care 8: 1087. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-996X.001087

Abstract

Background: The prevalence and severity of obesity continue to increase worldwide and this, next to risks for example for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, strongly increases the risk of multiple cancer types. Despite this, obesity is often not discussed in the consultation room in at risk populations. This study investigates knowledge gaps and communication needs for patients and health care providers (HCPs) in discussing obesity and (pre)cancer in oncological care. Methodology: We performed a mixed-methods study combining a cross-sectional questionnaire study and focus group interviews. Participants, HCPs and patients, were recruited in a university hospital setting. Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used to analyze the questionnaires. Results: In total 104 HCPs and 75 patients participated in the questionnaire study, and 3 focus interviews were conducted. Significant knowledge gaps among HCPs and patients regarding the link between obesity and cancer were revealed. HCPs showed an important disparity on obesity-associated cancer risk within and outside one’s specialty. Patients were little aware of obesity-associated cancer risks. Focus groups revealed communication gaps with time restrictions as the main barrier for HCPs. Patients underscored the importance of the topic but also the need for an individualized approach with a focus on timing and circumstances. Conclusion: Knowledge gaps and barriers in discussing obesity exist in HCPs as well as patients and should be addressed by training and normalization of the topic using effective and timely communication. Lifestyle and weight optimalisation should be an indispensable part of the journey in at risk populations and pre-oncological setting given the importance of disease prevention and quality of life.

Keywords: Oncology; Prevention; Endometrial cancer; Colon cancer; Postmenopausal breast cancer; Communication

Introduction

In 2023, 50% of the Dutch population aged 18 years or older had overweight (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25kg/m2) which includes 15.4% having obesity (≥BMI 30kg/m2). [1,2] It is expected that this percentage of 50% will increase to 62% in 2040 [3]. Worldwide, there is an identical pattern of increasing prevalence and severity of overweight and obesity, especially in westernized countries [4]. Obesity is a significant lifestyle factor, comparable to smoking and alcohol consumption. It strongly increases risk factors for a plethora of diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In more recent years, obesity and the associated metabolic disturbances have been shown to pose a significant risk factor for at least 13 cancer types, including endometrial cancer, postmenopausal breast cancer in women, and colon cancer in men [5]. In strongly obesity-associated cancer types, 50% is directly attributable to obesity [6,7]. Several studies have additionally demonstrated a higher cancer-specific (breast, colorectal, prostate) overall mortality [8,9]. Weight reduction is thus an important secondary/tertiary prevention measure and may further improve quality of life, therapy effectiveness and reduce risk of treatment complications [10].

There are strong indications that the relation between obesity and cancer is not widely known in the lay public contrasting the relation between smoking and lung cancer or obesity and diabetes, which have been focus of extensive governmental campaigns [11]. Pursuit of good health and dissatisfaction with appearance are among the strongest motivators for losing weight, (obese) people thus need prior knowledge on the obesity-associated health risks before it can act as a motivator for weight reduction and better health [3,6].

Health care professionals (HCPs) are often well aware of the consequences of obesity in their own specialty. It is uncertain to what extent similar awareness exists for non-specialty related consequences of obesity. This is important, as this may influence the extent to which HCPs are willing and comfortable to discuss obesity risks. This discussion is however important, as this may lead to referral to combined lifestyle intervention programs (CLI), which has been established in the Netherlands. CLI is a two-year program with focus on behaviour modification through nutrition and physical activity [12,13].

The Aim of this Study is Twofold.

- An inventory of current knowledge gaps in both HCPs and patients in (pre-) oncology concerning the relationship between obesity and cancer.

- Exploration of communicative requirements and challenges for adequate information provision and uptake of constructive dialogues concerning obesity in the consultation room.

Methods

We performed a mixed methods study including cross-sectional questionnaires and focus interviews among HCPs and patients consulting the Organization of European Cancer Network (OECI) accredited oncology center at Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands. Local ethics committee approval was obtained (IRB approval number 2022-3162). A waiver of informed consent was granted for the questionnaires in view of the one-time survey, which was non-invasive nor addressed any sensitive topics. All participants in the focus group participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Signed consent forms were collected and securely stored in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Questionnaires

The study included a different set of questionnaires for patients and HCPs. Both questionnaires included questions concerning baseline characteristics, knowledge about obesity in general, and the relative obesity-attributable risk for the onset of 30 wellknown diseases. The latter enquired about the association between obesity and the disease with the response options “no”, “light”, “light-moderate”, “moderate”, “moderate-strong” and “strong”, which were combined in four categories during analyses.

The patient questionnaire included the Motivation for Weight Loss Scale, developed and validated by Meyer et al [14]. This scale was linguistically validated in Dutch using a formal back-and-forth translation test. Notably, factor three contained two items that resulted in the same question in Dutch, and thus merged into a single item. The scale and its factors had high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients of 0.800 (Factor 1: health), 0.938 (Factor 2: appearance in relation to others), and 0.912 (Factor 3: appearance in relation to oneself)). Patients were also asked about their willingness to lose weight and their interest in CLI. The HCPs questionnaire further assessed engagement in, and barriers for, obesity-related conversations.

Qualtrics XM® was used to create and distribute the questionnaires.

The questionnaires for HCPs were distributed between March 8, 2022 and June 23, 2022. The questionnaires for patients were distributed between March 2023 and January 2024. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Focus Interviews

Focus interviews elaborated on findings obtained in the questionnaires and exploration of the intricacies of interactions between HCPs and patients regarding lifestyle changes. Interview questions were structured by the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [15], emphasizing quality of motivation; and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [16], focusing on intentions influenced by attitudes, subjective, normative, and perceived behavioural control, within the broader context of oncological care along with potential strategies to enhance this communication. Focus interviews, lasting between 45 and 60 minutes, were separately conducted for HCPs (n=2) and patients (n=1)

Participants

HCPs

We included HCPs working in the oncology divisions of gynecology, surgery, and gastroenterology, including the specialists in these fields and supporting medical oncologists, and radiotherapists, and (specialized) nurses. The specialties were selected in view of the strongly obesity-linked cancer types treated here. All HCPs were recruited through face-to-face interactions and targeted email invitations. This approach ensured a varied representation of perspectives from diverse healthcare roles and specialties involved in oncological care in a tertiary hospital. This approach was chosen to see which challenges were universal across specialties. Data saturation among the HCP focus group interviews was achieved, as no new themes or insights emerged from the final sessions.

Patients

Patients attending the (pre-) oncology departments of gynecology, surgery, and gastroenterology with symptoms possibly related to obesity-related cancer (an at-risk population), were approached for participation in the questionnaire part. They were contacted by email or phone via a research assistant and questionnaires were sent digitally. Focus group participants were invited in the outpatient departments and also participated in the questionnaire part. Notably, they suffered from different cancer types and were at different stages of their treatment or rehabilitation to ensure a varied representation of opinions.

Statistical Analysis

Questionnaires were analyzed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM®). Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, Mann-Whitney U test and the Friedman test with Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons were used to analyze the questionnaires. Data were reported as numerical values and percentages, or alternatively, as mean (median) and standard deviation (interquartile range), depending on the normality of the distribution. Graphs were designed or optimized in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe®).

Focus interviews used voice recordings as the primary source. Transcription was done using Amberscript® (version 2023) [17]. Data were analyzed using NVivo (10 essentials) [18], a qualitative data analysis software (Lumivero®), allowing for systematic organization and interpretation of textual information. Coding of the interviews facilitated the identification and categorization of key themes and patterns that emerged from the discussions.

Results

Questionnaires

In total 165 HCPs were approached of whom 104 (63%) participated (88% (n=92) complete). 170 patients were approached, of whom 52% (n=88) participated (85% (n=75) complete).

HCPs and patients differed significantly in age, BMI and level of education (all p<0.01), male/female ratio was similar (p=0.87). Of note, not all variables were available in both groups (Table 1).

|

Characteristics |

Health care professionals n=104 (%) |

Patients n=75 (%) |

P-value |

|

Sexa |

0.87 |

||

|

Female |

78 (75) |

51 (77.3) |

|

|

Male |

25 (24) |

14 (21.2) |

|

|

Not provided |

1 (1) |

1 (1.5) |

|

|

Age (y)b |

<0.01 |

||

|

<40 |

48 (46.2) |

1 (1.3) |

|

|

40-60 |

49 (47.1) |

33 (44.0) |

|

|

>60 |

7 (6.7) |

21 (28.0) |

|

|

BMIc |

<0.01 |

||

|

Normal (18-25) |

70 (67) |

26 (39.4) |

|

|

Overweight (25-30) |

25 (24.5) |

20 (30.3) |

|

|

Obesity (>30) |

9 (8.5) |

20 (30.3) |

|

|

Level of educationd |

<0.01 |

||

|

Primary/high school |

0 (0) |

11 (14.7) |

|

|

Higher/tertiairy education |

102 (98.1) |

52 (69.3) |

|

|

Other |

2 (1.9) |

3 (4.0) |

|

|

Function in MUMC |

|||

|

Medical doctor |

60 (57.7) |

||

|

Other† |

44 (42.3) |

||

|

Department |

|||

|

Surgery |

39 (37.5) |

||

|

Gynaecology |

22 (21.2) |

||

|

Gastroenterology |

13 (12.5) |

||

|

Oncology |

24 (23.1) |

||

|

Other |

6 (5.8) |

||

|

Table 1 legend: y = year; BMI = Body Mass Index. Mann-Whitney U-test applied for continuous data; Chi-squared test applied for categorical data. Missing patients: a:9; b:20; c:9; d:9; e:9; f:9; g:10; † Other includes nurse, nurse specialist, physician assistant. |

|||

Table 1: Characteristics of HCPs and patients.

Patients

In total, 59% (66%) of patients were well-informed about the BMI threshold indicating overweight (obesity) although less in obese participants. (Table 2)

65% (95%) of overweight (obese) patients expressed a desire to lose weight either at present or in the future. Among obese patients, 68% expressed an interest in participating in a CLI program. Importantly, 30% were not previously aware of the existence of such a program in the Netherlands and only 15% were aware of healthcare insurance coverage. (Table 2)

|

Patients divided by BMI groupa |

HCPs |

|||||

|

Research questions |

P-value |

|||||

|

Total N (%) |

BMI<25 |

BMI25-30 |

BMI>30 |

|||

|

Knowledge BMIb |

||||||

|

Overweight: BMI>=25 |

34 (58.6) |

16 (69.6) |

13 (68.4) |

5 (31.3) |

<0.01 |

82 (88.2) |

|

Obesity: BMI>=30 |

38 (65.5) |

14 (60.9) |

16 (84.2) |

8 (50) |

0.09 |

74 (79.6) |

|

Awareness CLIa |

0.41 |

|||||

|

Yes |

44 (66.7) |

19 (73.1) |

11 (55) |

14 (70) |

81 (87.1) |

|

|

No |

22 (33.3) |

7 (26.9) |

9 (45) |

6 (30) |

12 (12.9) |

|

|

CLI HI coverage awarenessa |

0.23 |

|||||

|

CLI always covered by HI |

25 (37.9) |

8 (30.8) |

6 (30) |

11(55) |

40 (43) |

|

|

CLI sometimes covered by HI |

20 (30.3) |

11 (42.3) |

6 (30) |

3 (15) |

35 (37.6) |

|

|

CLI never covered by HI |

21 (31.8) |

7 (26.9) |

8 (40) |

6 (30) |

18 (19.4) |

|

|

Interested in weight reductionf |

<0.01 |

|||||

|

Yes |

29 (43.9) |

2 (7.7) |

11 (55) |

16 (80) |

||

|

In the future |

9 (13.6) |

4 (15.4) |

2 (10) |

3 (15) |

||

|

Uncertain |

5 (7.6) |

4 (15.4) |

0 (0) |

1 (5) |

||

|

No |

23 (34.8) |

16 (61.5) |

7 (35) |

0 (0) |

||

|

Interested in a CLIc |

0.00 |

|||||

|

Yes |

25 (39.1) |

8 (30.8) |

4 (21.2) |

13 (68.4) |

||

|

Uncertain |

24 (37.5) |

9 (34.6) |

10 (52.6) |

5 (26.3) |

||

|

No |

15 (23.4) |

9 (34.6) |

5 (26.3) |

1 (5.3) |

||

|

Table 2 legend: Categorical data is presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Chi-square test applied. BMI = Body Mass Index; CLI= Combined lifestyle intervention; HI= Health Insurance. Missing: a:9; b:17; c:11 |

||||||

Table 2: Patient and Health Care Professionals (HCP) awareness regarding BMI.

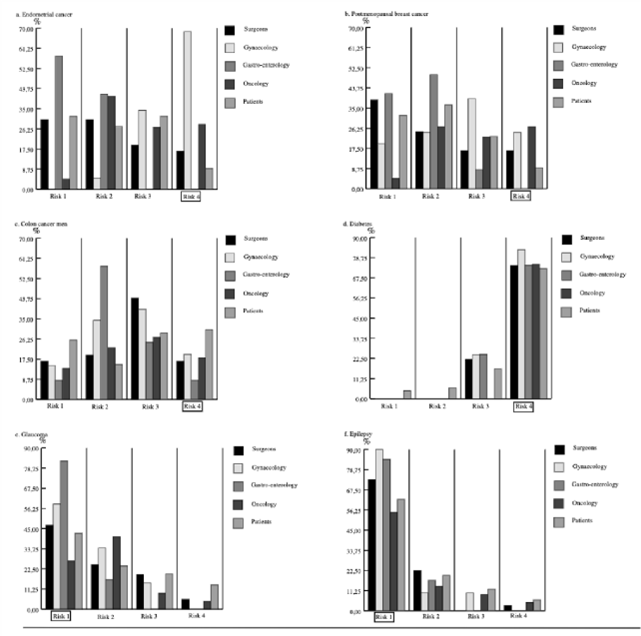

Knowledge of overweight/obesity as cancer development risk factor was poor (Figure 1a-c). This contrasted good awareness of the relation between obesity and development of diabetes (Figure 1d). Answer reliability was checked with a number of non-obesity associated conditions including glaucoma and epilepsy. Patients rated potential reasons for weight loss on a scale of 1 (absolutely not) to 4 (a lot) across three factors. The factor medians differed significantly, χ2(2)=105.16, p<.0005 and Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons indicated significant differences between all factors (II p<.0005) Health was the primary driver for weight loss for patients (median 3.57; interquartile range 3.00-3.86), followed by their appearance in relation to themselves (median 2.00; interquartile range 1.33-2.83). Appearance in relation to others was least important (median 1.10; interquartile range 1.00-1.70).

Figure 1: HCP and Patients presumed relative obesity risk for a number of health conditions. The figure illustrates the risk levels (ranging from 1-4, outlined with the appropriate risk assessment) associated with obesity for both HCP and patients concerning a number of health conditions. Risk level 1 indicated no risk, while risk level 4 indicates a high risk.

HCPs

HCPs were mostly familiar with the CLI program (87%), although less up to date regarding the refunding criteria (38%). (Table 2)

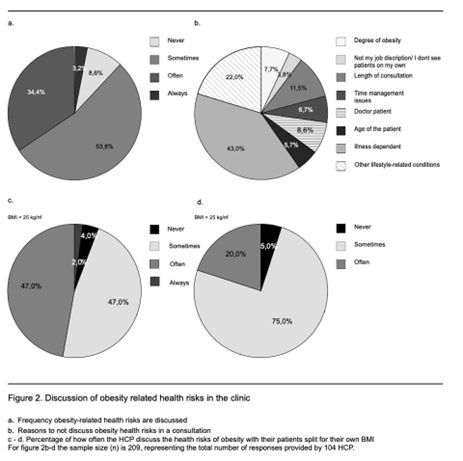

HCPs were generally aware of obesity-related risks for their own specialty, however much less of newer knowledge or knowledge outside their area of expertise. This was illustrated well in gynecology HCPs assessing the obesity-related risk for endometrial cancer (Figure 1a). ‘Confounder diseases’ (i.e. non-obesity-related diseases, Figure 1e-f) were well recognized, supporting that honest and not socially desirable answers were given. A minority of HCP (34.4%) regularly discussed obesity risks with their patients, 53.8% sometimes and nearly 8.6% never did (Figure 2a). The most important reasons to not discuss included the type of disease and treatment phase (76.3%), the presence of multiple lifestyle conditions (49.5%), and time constraints (40.9%) as shown in Figure 2b. Interestingly that normal weight HCPs (BMI <25) discuss the risks more frequently than overweight/obese HCPs (47% vs. 20%, respectively, Figure 2c-d).

Focus Group Discussions

The HCPs focus group discussions highlighted time constraints as a significant challenge. Simultaneously, it was acknowledged extending consultation time might not be a practical solution due to the information load patients receive. Cross-specialty knowledge was noted to be beyond the scope of most HCP’s expertise. A notable interest in training in motivational interviewing techniques was expressed as a potential avenue to improve the required communication tools and engagement. Further suggested remedies included a referral system to (in-house) lifestyle clinics, the success of which would be contingent on effective communication between the HCPs and dedicated lifestyle coaches.

Focus group session analysis further highlighted the importance to connect obesity and (pre-) cancer risk and treatment in communication between healthcare providers and patients. Patients underscored the importance of direct, empathetic communication and personalized support, acknowledging the challenges they face. As one participant put it: ‘’listen well, give personalized advice, and then refer to maybe a central information point or something, but not like: ‘here’s a flyer?’ […] Yes really tailored advice.” It illustrates the clear preference for truly personalized guidance over generic recommendations, emphasizing the importance of feeling heard and supported. Patients also noted that while addressing obesity is important, it should be accompanied by practical tools and not just general advice. As one stated: “I think it’s very, very important […] but especially not just mentioning it, but providing the tools.”

Importantly, timing was confirmed to be essential to raise this sensitive topic, but an optimal time point was individual. Some patients experienced frustration when weight-related issues were brought up at inappropriate or emotionally difficult moments, such as during the initial diagnosis. One patient expressed: “During the bad news conversation, I don’t need to hear that I’m overweight […] Now it’s about offering the right tools at the right time. And listening to what a person needs and actively asking.” This underscores the importance of timing, tone, and the delivery of clear, actionable support without judgment.

The need to avoid blame was also a recurring theme. Patients described how feeling blamed or shamed, particularly during vulnerable moments, negatively affected their trust in HCPs. One participant shared: “I really don’t need blame. […] it’s already bad enough at that moment.” This highlights the need for HCPs to approach weight-related discussions with empathy and sensitivity, avoiding language that could unintentionally stigmatize or alienate patients.

Patients all agreed on the importance of discussing the relation between (over)weight and cancer but were surprised by the lack of proactive information given by the HCPs. A number of effective tools were identified but their applicability depended on patients’ mental states and readiness for adjustment. Barriers to weight loss included a lack of post-treatment support, the overwhelming priority of cancer-related health issues, and the unclear balance between treatment and weight loss. In summary, the analysis uncovered knowledge gaps and communication challenges in discussing the risk of obesity in (pre-) cancer care, while emphasizing the need for personalized, non-judgmental, and timely support.

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be categorized into three different themes: knowledge, communication (gaps) and barriers.

Knowledge

There are clear knowledge gaps, even among HCPs specialized in oncology, regarding the link between obesity and (pre-) cancer conditions. While HCPs dispose of highly specialized knowledge, especially in academic settings, they often lack generalistic insight into broader lifestyle-related health risks that affect multiple organ systems. This specialization, though unavoidable, limits their ability to integrate general preventive lifestyle advice into routine care.

To bridge this gap, the participating HCPs acknowledged a need of improved knowledge and communication strategies, particularly motivational interviewing. This could be facilitated through topdown hospital-wide training initiatives. The establishment of structured in-house lifestyle clinics can further supply appropriate, specialized guidance while alleviating pressure on HCPs.

Studies confirm that such referral systems can effectively support patients in making sustainable lifestyle changes [19,20].

Patients possessed very limited knowledge about the association between obesity and cancer, which is an essential condition to initiate behavioural change. The effect of knowledge regarding the effect of negative lifestyle factors on health is nicely illustrated by the decreases in teenage smoking due to long-term governmental information campaigns [19,20]. Similar attention has not been given to obesity risks so far but is necessary to motivate people to alter their lifestyle. It is incumbent upon central governments and HCPs alike to raise awareness of these risks through campaigns, leveraging the significant role of the media [21]. Encouragingly, a recent publication by the Dutch federation of cancer patients reported that 70% of cancer patients in a large questionnaire study valued a discussion of lifestyle with HCPs of whom the majority preferred the HCPs to start this discussion [22-25] This further underscores the need for additional (communication) skills and referral options.

Communication Gaps

Our patients did not recognize or recall all lifestyle advice communicated by their HCPs, but indicated to value such advice, as also suggested by the literature here above. This suggests that current communication strategies, used by HCP, are not effective in making a lasting impact. Patients who experience effective communication with their HCPs are more willing to turn constructive advice into behavioural changes and more often express satisfaction with their care [26]. Thus, it is of utmost importance to train all HCPs to effectively advise patients on the delicate topic of lifestyle during consultations and using motivational interviewing such that the message is retained. HCPs are in an excellent position to plant a seed for change through establishment of a logical connection between lifestyle choices and specific health conditions, enhancing patient comprehension and retention [27].

Importantly, however, patient motivation cannot rely solely on the consultation room. Lifestyle messaging should resonate throughout the hospital, from brochures and waiting room screens to hospital design that subtly nudges healthy choices. This broader environment supports and reinforces the communication started by HCPs and creates a culture where lifestyle care becomes standard rather than exceptional.

Barriers

Several barriers were identified in line with literature. Optimal timing of the topic is considered delicate, in particular in the context of a (pre) cancer diagnosis. Further are time constraints important barriers for effective lifestyle discussions [28-31]. To overcome these barriers, a structured in-house referral system to trained lifestyle coaches is essential. These findings align closely with the two theoretical frameworks underpinning the setup of our study (TPB and SDT). According to TPB, behaviour is influenced by intention, shaped by attitude, subjective norms, and by perceived behavioural control.

The observed lack of awareness about obesity-related cancer risks, combined with the perceived sensitivity of the topic, may reduce patients’ sense of control and hinder the intention to initiate lifestyle changes. SDT emphasizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in fostering intrinsic motivation. Patient feedback in this study highlighted the need for empathetic communication, personalized advice, and appropriate timing to initiate lifestyle change-factors that support these core psychological needs [15,16,32]. By educating patients on the causal relationships between behaviour and disease, and offering those tools and support to act, we strengthen their capacity to make meaningful changes. This not only improves long-term health outcomes but also restores a crucial degree of autonomy, allowing patients to become active participants in their own care journey [33,34]. Thus, promoting behavioural change requires not only adequate knowledge and tools but also a patient-centered approach that fosters autonomy and emotional safety.

Importantly, lifestyle coaches can provide consistent, in-depth information and empower the patient to become intrinsically motivated for change. This circumvents the issue with increasingly specialized knowledge in HCPs, outpatient clinic time constraints and ensures that patients receive balanced information, motivational interviewing, and guidance on health-related lifestyle factors related to their entry complaint.

It remains crucial for healthcare professionals to breech the topic during consultations to make the first link between lifestyle and illness and thus encourage patients to take action, the so called ‘teachable moment’. This approach aligns also with results from prehabilitation clinics that show patients are motivated to change their lifestyle for concrete health goals including speedier treatment recovery [35,36]. Education on the causal relation between obesity and disease empowers patients and significantly increases the likelihood of successful lifestyle modification including quitting smoking after (suspicion of) a myocardial infarction, lung cancer diagnosis or cervical cancer [32,37-42]. Empowering patients with knowledge about the connection between obesity and cancer does more than informing, it motivates. Understanding the impact of lifestyle on treatment outcomes and disease prognosis gives patients a sense of agency, which is particularly valuable in the (pre-) oncological setting where control often feels lost.

Limitations

Although conducted in an academic center, the inclusion of multiple medical specialties ensures diversity in perspectives. In addition, the demonstrated knowledge gaps in expert HCP assume at least similar challenges in the non-academic setting.

Strong Points

The utilization of a mixed-method design using both questionnaires and focus groups enabled a nuanced and expansive exploration of information beyond the confines of the questionnaires alone. This study’s design facilitated the comparative analysis of HCP’s knowledge across diverse specialties, enabling a better external validity of the results. This study combined the HCP and patient views, which is essential to better understand the barriers and room for improvement.

Conclusion

We demonstrated knowledge gaps and barriers in discussing obesity-related risks in HCPs and patients alike. HCPs showed a significant disparity in their knowledge of obesity-associated cancer risks between within and outside specialty knowledge, while patients had limited awareness of these risks altogether. These knowledge gaps can be addressed by training. Normalization of the topic is important for effective and timely communication and to benefit from the ‘Teachable Moment’ caused by (the possibility of) a disease. A well-organized referral system for lifestyle care could be supportive of an effective implementation of lifestyle in (pre-) oncological care. Lifestyle and weight (reduction) should be an indispensable part of the (pre-) oncological journey in view of the importance of disease prevention and quality of life.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs I. Deckers and Mrs Johanna C. Minitt for the valuable help in the formal back-and-forth translation of the questionnaire.

Key Message

Globally, the incidence and severity of obesity continue to increase. It is well established that obesity is associated with an elevated risk of multiple diseases, including 13 types of cancer. This study demonstrates that knowledge among health care providers is incomplete, especially on obesity-related cancer risks outside their respective working fields. Patients are poorly aware of obesityrelated cancer risks. Training programs and normalization of the discussion around obesity with a patient-centered approach are identified as approaches that may help to bridge these gaps.

References

- de Hollander E, Hupkens C, van Dorsselaar S, Wendel-Vos W, Kemler E, et al. (2022) De Leefstijlmonitor: Cijfers voor gezondheidsbeleid. TSG. 100: 98-106.

- RIVM (2024) Overweight | Adults [Internet] [cited 2024 Nov 29].

- RIVM (2018) The Public Health Foresight Study 2018 [Internet].

- World Health Organisation (2024) Obesity and overweight [Internet].

- Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, et al. (2016) Body Fatness and Cancer-Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 375: 794-798.

- Anderson AS, Key TJ, Norat T, Scoccianti C, Cecchini M, et al. (2015) European Code against Cancer 4th Edition: Obesity, body fatness and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 39: S34-S45.

- Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M (2008) Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. The Lancet. 371: 569-578.

- Petrelli F, Cortellini A, Indini A, Tomasello G, Ghidini M, et al. (2021) Association of Obesity With Survival Outcomes in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open [Internet] 4: e213520.

- Rivera-Izquierdo M, de Rojas JP, Martínez-Ruiz V, Pérez-Gómez B, Sánchez MJ, et al. (2021) Obesity as a risk factor for prostate cancer mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 280,199 patients. Cancers (Basel). 13: 4169.

- Powers-James C, Morse M, Narayanan S, Ramondetta L, Lopez G, et al. (2024) Integrative Oncology Approaches to Reduce Recurrence of Disease and Improve Survival. Curr Oncol Rep 26:147-163.

- Scherer PE, Hill JA (2016) Obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: a compendium. Circ Res [Internet] 118: 11.

- Oosterhoff M, de Weerdt A, de Vries E, Feenstra T, de Wit A (2023) Jaarrapportage monitor gecombineerde leefstijl interventie (GLI)

- Mohseni M, Kuckuck S, Meeusen REH, Jiskoot G, Lengton R, et al. (2023) Improved Physical and Mental Health After a Combined Lifestyle Intervention with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Obesity. Int J Endocrinol Metab 21: e129906.

- Meyer AH, Weissen-Schelling S, Munsch S, Margraf J (2010) Initial development and reliability of a motivation for weight loss scale. Obes Facts 3: 205-211.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 55: 68-78.

- Cameron R (2010) Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior Applied to the Use of Social Networking by College Students. University Honors Program.

- Amberscript: Audio & Video Transcription | Speech-to-text [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 3].

- NVivo 10 essentials : your guide to the world’s most powerful data analysis software : Edhlund, Bengt M [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 3].

- Riley KE, Hay JL, Waters EA, Biddle C, Schofield E, et al. (2019) Lay Beliefs about Risk: Relation to Risk Behaviors and to Probabilistic Risk Perceptions. J Behav Med [Internet] 42: 1062-1072.

- Naslund JA, Kim SJ, Aschbrenner KA, McCulloch LJ, Brunette MF, et al. (2017) Systematic Review of Social Media Interventions for Smoking Cessation. Addictive behaviors [Internet] 73: 81-93.

- Nederlandse Federatie van Kankerpatiënten organisaties. Rapportage Doneer je ervaring peiling leefstijl. 2024 Oct 3

- Kuijpers MMT, van Veenendaal H, Engelen V, Visserman E, Noteboom EA, et al. (2022) Shared decision making in cancer treatment: A Dutch national survey on patients’ preferences and perceptions. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 31: e13534.

- Knudsen MD, Hjartåker A, Robb KA, Lange T De, Hoff G, et al. (2018) Improving Cancer Preventive Behaviors: A Randomized Trial of Tailored Lifestyle Feedback in Colorectal Cancer Screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet] 27: 1442-1449.

- Stevens C, Vrinten C, Smith SG, Waller J, Beeken RJ (2019) Acceptability of receiving lifestyle advice at cervical, breast and bowel cancer screening. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet] 120:19-25.

- Nederlandse Federatie Kankerpatiënten-organisaties (2024) Leefstijl bij kanker leeft onder patiënten, maar wordt niet altijd besproken.

- Rodrigues TRC, Buisonjé DR De, Keesman M, Reijnders T, Geer JE Van Der, et al. (2021) Facilitators of and Barriers to Lifestyle Support and eHealth Solutions: Interview Study Among Health Care Professionals Working in Cardiac Care. J Med Internet Res [Internet] 23: e25646.

- Stephenson J, Smith CM, Kearns B, Haywood A, Bissell P (2021) The association between obesity and quality of life: a retrospective analysis of a large-scale population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 21: 1990.

- Alexander SC, Østbye T, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Bastian LA (2007) Physicians’ Beliefs about Discussing Obesity: Results from Focus Groups. American Journal of Health Promotion. 21: 498-500.

- Hamilton K, Henderson J, Burton E, Hagger MS (2019) Discussing lifestyle behaviors: perspectives and experiences of general practitioners. Health Psychol Behav Med [Internet] 7: 290-307.

- Hidalgo KD, Mielke GI, Parra DC, Lobelo F, Simões EJ, et al. (2016) Health promoting practices and personal lifestyle behaviors of Brazilian health professionals. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 16:1-10.

- Hodsdon A, Smith NA, Story DA (2020) Preoperative communication between anaesthetists and patients with obesity regarding perioperative risks and weight management: a structured narrative review. Perioperative Medicine [Internet]. 9(1).

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1983) Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol 51: 390-395.

- Jiralerspong S, Goodwin P (2016) Obesity and Breast Cancer Prognosis: Evidence, Challenges, and Opportunities. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 34: 4203-4216.

- Shaikh H, Bradhurst P, Ma L, Tan C, Egger S, et al. (2020) Body weight management in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD012110.

- Molenaar CJL, Minnella EM, Coca-Martinez M, ten Cate DWG, Regis M, et al. (2023) Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation on Reducing Postoperative Complications and Enhancing Functional Capacity Following Colorectal Cancer Surgery. JAMA Surg 158: 572-581.

- Gennuso D, Baldelli A, Gigli L, Ruotolo I, Galeoto G, et al. (2024) Efficacy of Prehabilitation in cancer patients: an Rcts systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 24: 1302.

- Chellini E, Gorini G, Gasparrini A, Grazzini G, Iossa A, et al. (2012) Cervical cancer screening visit as an occasion for counseling female smokers to quit. Tumori [Internet]. 98: 27-32.

- Hall S, Bishop AJ, Marteau TM (2003) Increasing readiness to stop smoking in women undergoing cervical screening: evaluation of two leaflets. Nicotine Tob Res [Internet] 5: 821-826.

- Maula A, Kendrick D, Kai J, Griffiths F (2021) Evidence generated from a realist synthesis of trials on educational weight loss interventions in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 38: e14394.

- Katon J, Reiber G, Williams MA, Yanez D, Miller E (2013) Weight loss after diagnosis with gestational diabetes and birth weight among overweight and obese women. Matern Child Health J 17: 374-383.

- Santoso JT, Crigger M, English E, Wan J, Likes W (2012) Smoking cessation counseling in women with genital intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol [Internet] 125: 716-719.

- Tammemägi MC, Berg CD, Riley TL, Cunningham CR, Taylor KL (2014) Impact of lung cancer screening results on smoking cessation. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet] 106: dju084.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.