Multimodal Strategies to Improve Healthcare Workers’ Compliance in the Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs)

by Giovanna Sepe1*, Giovanni Cirillo2

1Direzione Sanitaria OO.RR. Area Nolana, ASL NA3 Sud, Nola (NA)

2Department of Mental and Physical Health and Preventive Medicine, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples, Italy.

*Corresponding author: Dr. Giovanna Sepe, Direzione Sanitaria OO.RR. Area Nolana, ASL NA3 Sud Via Seminario, 80035 Nola (NA), Italy.

Received Date: 3 October 2025

Accepted Date: 14 October 2025

Published Date: 16 October 2025

Citation: Sepe G, Cirillo G (2025) Multimodal Strategies to Improve Healthcare Workers’ Compliance in the Control of HealthcareAssociated Infections (HAIs). Advs Prev Med Health Care 8: 1082. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-996X.001082

Abstract

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) represent a major threat to patient safety, particularly in hospital environments. Despite the well-documented effectiveness of hand hygiene in preventing HAIs, compliance among healthcare workers remains suboptimal. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates for a multimodal strategy to improve adherence to hand hygiene practices. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of multimodal strategies and electronic monitoring tools in improving hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers at the “Santa Maria della Pietà” Hospital in Nola, Italy. The study included healthcare workers from multiple hospital departments and used a comparative design: one group received targeted WHO-based training and feedback interventions, while another did not. Hand hygiene performance was evaluated using both direct observation and electronic monitoring systems. Performance indicators included adherence to the WHO’s “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene,” time spent washing hands, and completeness of technique, with additional analysis using fluorescent markers and ultraviolet (UV) evaluation to visualize residual contamination. The trained group showed a statistically significant improvement in compliance compared to the control group. Adherence to hand hygiene increased in all “five moments,” particularly before aseptic procedures and after patient contact. The use of fluorescent markers confirmed a higher quality of handwashing among trained staff. Electronic feedback further reinforced behavioural change. Multimodal strategies, including targeted training, performance feedback, and visual aids, effectively enhance hand hygiene compliance among healthcare personnel. Electronic monitoring tools proved useful in assessing real-time performance and providing immediate feedback. Strengthening the culture of hand hygiene within hospital settings is essential for reducing HAIs and improving patient safety.

Keywords: Hand hygiene; Healthcare-associated infections; Compliance; Multimodal strategy; WHO; Electronic monitoring; Patient safety

Introduction

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are a major cause of morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs worldwide. Defined as infections not present or incubating at the time of admission, HAIs typically emerge 48 hours or more after hospitalization, and are often linked to invasive procedures and the hospital environment itself [1]. Common HAIs include catheterassociated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), surgical site infections (SSI), and bloodstream infections (BSI), all of which are associated with significant patient risk and systemic burden [2].

Among the various infection control measures, hand hygiene is universally recognized as the single most effective strategy to prevent the transmission of pathogenic microorganisms in healthcare settings. Since the pioneering observations of Semmelweis in the 19th century, hand hygiene has remained at the forefront of infection prevention, supported by extensive empirical evidence [3]. Nonetheless, adherence to hand hygiene practices among healthcare workers (HCWs) remains suboptimal. Studies report average compliance rates below 40% in acute care settings without active intervention, and rates as low as 17% in long-term care facilities in Italy [4,5].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized this persistent gap and launched a series of global initiatives, including the annual “Save Lives: Clean Your Hands” campaign, celebrated on May 5th since 2005. In its 2009 Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care, the WHO introduced the concept of the “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene”, a patient-centered approach identifying five critical instances when hand hygiene should be performed: before patient contact, before aseptic procedures, after body fluid exposure, after patient contact, and after contact with patient surroundings [1].

To address the behavioural, infrastructural, and cultural barriers to compliance, the WHO recommends a multimodal strategy encompassing five core components: (1) system change (ensuring access to hand hygiene supplies), (2) training and education, (3) monitoring and feedback, (4) workplace reminders, and (5) institutional safety climate. Numerous studies have validated the efficacy of this approach, demonstrating significant improvements in hand hygiene compliance and reductions in HAIs when applied consistently [6,7]. Despite these advances, several factors continue to impede compliance. These include time constraints, forgetfulness, and lack of awareness, skin irritation, low risk perception, and limited availability of hand hygiene resources [8]. Notably, healthcare workers are more likely to perform hand hygiene after potential self-exposure than before patient contact, reflecting a tendency to prioritize self-protection over patient safety [9].

In recent years, electronic monitoring technologies have emerged as a complementary tool for auditing and improving hand hygiene behaviour. These systems range from badge-based sensors to motion-activated dispensers, and offer real-time data collection and feedback. When integrated with multimodal strategies, electronic monitoring has shown promise in reinforcing compliance and maintaining long-term behaviour change [10,11].

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical role of hand hygiene in preventing viral transmission in both healthcare and community settings. While public awareness has increased, studies suggest that improvements in compliance during the pandemic may be temporary and dependent on perceived risk rather than sustainable practice [12]. This reinforces the need for permanent institutional investment in hygiene culture and education. In this context, fostering a “culture of hand hygiene” within healthcare institutions has become an essential objective. The WHO defines this as a system-wide commitment where leadership, training, and peer influence align to support infection prevention behaviours at all levels. Leaders, supervisors, and frontline staff must collaborate in reinforcing norms, monitoring performance, and providing ongoing feedback [1,13].

The Italian national strategy, aligned with WHO principles, includes the PAICA (Piano Annuale Infezioni Correlate all’Assistenza) framework, which promotes systematic surveillance, staff training, and antimicrobial stewardship across healthcare facilities. This includes the use of microbial alert systems, risk assessment tools, and structured reporting procedures to detect and manage infection outbreaks [14].This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a WHO-aligned multimodal strategy, integrated with electronic hand hygiene monitoring tools, in improving compliance among healthcare workers at “Santa Maria della Pietà” Hospital (Nola, ASL Napoli 3 Sud). The intervention targeted a selection of clinical departments and included both trained and untrained cohorts, enabling a comparative analysis of behaviour change and hand hygiene quality. Data were collected using direct observation, fluorescent gel-based evaluation, and automated feedback systems. By integrating organizational protocols, observational tools, and technological innovation, the study seeks to contribute evidence toward best practices for sustaining hand hygiene adherence and reducing HAIs in hospital settings.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Participants

This study was conducted at the “Santa Maria della Pietà” Hospital in Nola, under ASL Napoli 3 Sud, between February and March 2023. It involved healthcare workers (HCWs) from multiple units-Anesthesia and Intensive Care, Operating Theater, Gynecology and Obstetrics, Pediatrics, and Neonatology-who were actively engaged in patient care. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Although informed consent was waived due to the study’s observational nature and alignment with internal quality improvement practices, ethical approval was secured in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Study Design and Groups

We employed a comparative observational design to evaluate the impact of a structured hand hygiene intervention. Two groups were defined: the intervention group composed of HCWs who received structured training and participated in WHO-aligned “Five Moments” awareness sessions; and the control group, comprising staff from departments not exposed to this program during the study period.

Intervention Protocol

The multimodal intervention combined didactic, visual, and behavioural components. Infection prevention specialists conducted training sessions focused on WHO hand hygiene techniques, the epidemiology of healthcare associated infections (HAIs), and the rationale behind the Five Moments. Visual reminders-such as instructive posters-were strategically placed in clinical areas. Alcohol-based hand rub dispensers were positioned at every point of care to improve accessibility. Crucially, participants were shown their handwashing performance using UV-fluorescent gel: they applied gel before washing, and residual contamination was highlighted under ultraviolet light, reinforcing awareness of frequently neglected areas like fingertips and thumbs.

Data Collection Methods

We assessed hand hygiene adherence using a triad of methods:

- Direct Observation: Trained observers monitored whether HCWs performed hand hygiene correctly according to WHO criteria, noting opportunities, technique, and duration.

- UV-Fluorescent Gel Assessment: Following hand hygiene, hands were examined under UV to categorize technique effectiveness-“effective” (no residue), “partial” (residue in specific areas), or “ineffective” (widespread residue).

- Electronic Monitoring: Selected units were equipped with sensor-enhanced dispensers that recorded usage events anonymously, tracking frequency and timing across shifts and departments.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was compliance rate, calculated as the percentage of WHO-defined hand hygiene opportunities properly adhered to clinical moment, department, and professional role (physician, nurse, auxiliary) stratified this. Secondary outcomes included the quality of technique per UV evaluation, pre–post intervention changes in compliance, and correlation between observed adherence and dispenser sensor data.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS v.26.0. We summarized demographic characteristics and compliance statistics using descriptive measures. Group comparisons were made using chisquare tests for categorical variables, and paired t-tests assessed within-group improvements pre–post intervention. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. This methodological design was intended to produce robust, reproducible insights into the impact of the multimodal intervention on hand hygiene performance.

Results

Compliance Improvement across the WHO’s Five Moments

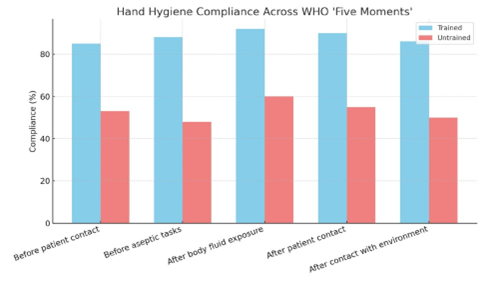

The implementation of a multimodal strategy incorporating WHOaligned training, visual reminders, and electronic feedback led to a marked improvement in hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers (HCWs) across all clinical units included in the study. The intervention’s impact was primarily evaluated in terms of adherence to the WHO’s Five Moments for Hand Hygiene. Results showed a consistent and significant increase in compliance among the trained group compared to the untrained cohort, with trained HCWs exceeding 85% adherence in all five categories. Specifically, compliance before patient contact reached 85% in the trained group, compared to 53% in the untrained group. Hand hygiene before aseptic tasks rose to 88% versus 48%, after exposure to body fluids to 92% versus 60%, after patient contact to 90% versus 55%, and after contact with the environment surrounding the patient to 86% versus 50% (Figure. 1 and table 1). These results highlight that WHO-based training not only raised awareness about critical hygiene moments but also translated into consistent behavioural change integrated into daily clinical practice.

Figure 1: Hand Hygiene Compliance across the WHO ‘Five Moments’ Comparing Trained and Untrained Groups.

|

WHO Moments |

Trained (%) |

Untrained (%) |

|

Before patient contact |

85 |

53 |

|

Before aseptic tasks |

88 |

48 |

|

After body fluid exposure |

92 |

60 |

|

After patient contact |

90 |

55 |

|

After contact with environment |

86 |

50 |

Table 1: Compliance across WHO ‘Five Moments.

Stratification by Department and Professional Role

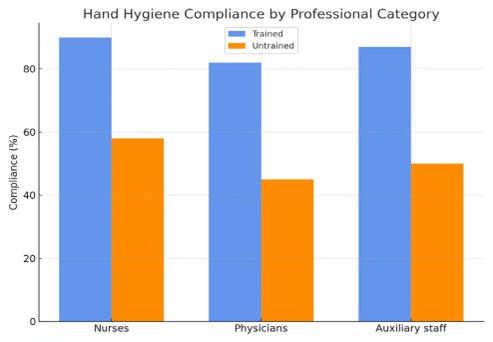

When analysed by department, it became evident that some clinical units, notably the Intensive Care Unit and the Operating Theater, had the lowest baseline compliance, often falling below 40%. This was likely due to the high procedural intensity and workload in these areas. However, these same departments also recorded the most significant improvements after the intervention, with compliance rates increasing to over 85%, suggesting the effectiveness of the strategy even in high-demand settings. The analysis by professional category further demonstrated the value of the training. Nurses achieved the highest compliance overall, with trained nurses reaching 90% compared to 58% in the untrained group. Physicians, who started at a lower baseline of 45%, increased to 82% post-training, indicating substantial behavioural change. Auxiliary healthcare staff also benefited, improving from 50% to 87%, which confirms that the intervention had a widespread impact across all levels of the care team (Figure. 2 and table 2).

Figure 2: Hand Hygiene Compliance by Professional Category Showing Improvements among Nurses, Physicians, and Auxiliary Staff.

|

Quality |

Trained (%) |

Untrained (%) |

|

Effective |

75 |

35 |

|

Partial |

20 |

47 |

|

Ineffective |

5 |

18 |

Table 2: Quality of Hand Hygiene Technique (UV Assessment).

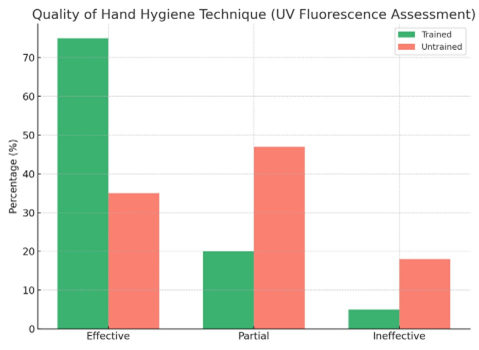

Quality of Technique Assessed via Fluorescent Marker

To assess the thoroughness and quality of hand hygiene, UV fluorescent gel was employed as an evaluative tool. Healthcare workers applied the gel before performing hand hygiene, and their hands were then examined under ultraviolet light to assess the presence of residual contamination. Among the trained HCWs, 75% performed hand hygiene effectively with no visible fluorescent traces, while 20% were partially effective, showing limited residue in areas such as wrists or nail beds, and only 5% were classified as ineffective due to the presence of large fluorescent patches. In comparison, only 35% of the untrained group achieved effective results, 47% were partial, and 18% were classified as ineffective (Figure. 3 and table 3). The most missed areas were the thumbs, fingertips, and the back of the hands, supporting prior findings in the literature that even self-reported adherence may not guarantee optimal technique without specific training. This visual method provided clear and impactful feedback to participants, reinforcing correct technique.

Figure 3: Quality of Hand Hygiene Technique Assessed with UV Fluorescence among Trained and Untrained Healthcare Workers.

|

Category |

Trained (%) |

Untrained (%) |

|

Nurses |

90 |

58 |

|

Physicians |

82 |

45 |

|

Auxiliary staff |

87 |

50 |

Table 3. Compliance by Professional Category.

Electronic Monitoring of Hand Hygiene Events

In parallel with direct observation and UV analysis, the study deployed electronic dispensers equipped with motion sensors to record hand hygiene events continuously and anonymously. Over 10,000 individual events were logged during the observation period. The data revealed a 30% increase in hand hygiene activity per shift in units where staff had received training. Usage patterns suggested that most hand hygiene events occurred during morning medication rounds and immediately following clinical procedures. These data indicate successful integration of hand hygiene into the routine clinical workflow. Moreover, the electronic dispensers provided real-time feedback through auditory or visual cues such as LED lights and soft chimes, which served as helpful reminders to HCWs. The strong correlation (r = 0.82) between sensor data and direct observations further supports the validity of electronic monitoring systems as reliable tools in routine infection prevention auditing.

Perception and Behavioral Change among Staff

Post-intervention surveys were conducted to evaluate staff perceptions regarding the training and the overall importance of hand hygiene. Among trained participants, 92% reported increased awareness of infection risk following the intervention, and 85% considered the training highly useful. A notable 70% stated that the UV gel exercise had changed their approach to handwashing, increasing attention to technique and duration. In contrast, the untrained group showed less confidence and engagement: only 45% believed colleagues performed hand hygiene adequately, 30% were uncertain about correct technique, and 15% cited discomfort or skin irritation as a cause for noncompliance. Initial skepticism about the use of electronic monitoring-especially concerns about being surveilled-diminished significantly once the feedback was shown to be anonymized, non-punitive, and constructive in purpose. These attitudinal shifts suggest that behaviour change is more likely to be sustained when staff perceive interventions as educational rather than disciplinary.

Temporal Trends and Long-Term Sustainability

To explore the durability of behavioural change, a follow-up assessment was conducted six weeks after the initial intervention. Although a slight decline in compliance was observed compared to peak post-intervention levels, the trained group maintained an average adherence rate of approximately 82%, which remained significantly higher than baseline. This result suggests that the intervention was successful in producing a degree of sustained change, even in the absence of continuous reinforcement. The ability to maintain improved behaviour over time is especially important in hospital environments, where daily pressures and workload can erode adherence. These findings reinforce the notion that multimodal strategies can produce meaningful, long-lasting improvements when thoughtfully implemented.

Statistical Significance of Outcomes

All observed differences between the trained and untrained groups across the five WHO moments were statistically significant, with p-values less than 0.001. Chi-square analyses confirmed that intergroup variations in hand hygiene behaviour were highly unlikely to be due to chance. Additionally, paired t-tests demonstrated significant within-group improvements from baseline to post-intervention for the trained group. These statistical findings support the robustness and reliability of the results, validating the efficacy of the multimodal strategy not only in enhancing compliance rates but also in improving the overall quality and sustainability of hand hygiene behaviours. Together, the combination of educational engagement, visual technique validation, and objective monitoring produced a comprehensive and evidence-based model for infection prevention in clinical practice.

Discussion

The findings of this study strongly support the effectiveness of a multimodal strategy in significantly improving hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers (HCWs) in a hospital setting. This approach, aligned with the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, combined educational training, visual prompts, and electronic monitoring to produce measurable and sustained behavioural change. Compliance increased not only in frequency but also in quality, with participants demonstrating improved technique in handwashing as confirmed through UV fluorescent gel analysis. The observed improvements were especially evident in the moments most often overlooked, particularly before aseptic procedures and after contact with the patient’s environment-key points identified in previous literature as vulnerable to neglect.

The WHO’s “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene” provided a robust and evidence-based framework for evaluating adherence, and the observed gains among trained staff suggest that these guidelines, when adequately reinforced, can lead to substantial behavioural modification. One of the most powerful components of the intervention was the use of visual and interactive tools during training, such as fluorescent gel under UV light, which provided immediate and intuitive feedback on the completeness of hand hygiene. This method enhanced participant awareness and was particularly effective in revealing commonly missed areas like the thumbs and fingertips. While relatively simple and low-cost, this strategy has been validated by several authors as a practical educational measure, and our results further confirm its value. The success of the educational component was also reinforced by the integration of physical reminders-such as posters located in key clinical areas-which likely contributed to the sustained awareness observed throughout the intervention. Educational sessions were structured around the rationale behind each of the five moments and emphasized the risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), ultimately helping HCWs to connect daily actions with patient safety outcomes.

These efforts align with previous research showing that educational programs are among the most effective tools to improve compliance, particularly when they include visual reinforcement and are repeated over time. Another important element of this study was the introduction of electronic hand hygiene monitoring systems (EHMS), which supplemented traditional observation techniques and provided reliable, real-time data on dispenser use and timing. The increase in electronically recorded events closely paralleled the direct observation findings, validating EHMS as a useful tool for routine monitoring. Furthermore, the presence of visual or auditory feedback, such as light signals or chimes, served as immediate cues for staff and likely enhanced overall adherence. Initially, some staff expressed concern about surveillance and privacy; however, once the feedback process was explained and anonymized reporting was guaranteed, those reservations diminished. This underscores the importance of contextualizing technology within a culture of safety and transparency, rather than using it as a tool of control. When implemented with a nonpunitive approach, EHMS can foster continuous improvement and complement manual observation without the associated limitations of bias or labor intensity.

The issue of sustainability is always critical when assessing behavioural interventions. Follow-up evaluations conducted six weeks after the intervention concluded revealed a slight decline in adherence, yet compliance rates remained significantly above baseline levels, indicating that the intervention had a lasting impact. This durability is particularly notable given the known tendency for hand hygiene compliance to regress once active monitoring ceases. It also highlights the importance of fostering a broader institutional culture that prioritizes infection prevention beyond sporadic campaigns. Leadership played an essential role in supporting this transformation. Departments in which supervisors or unit heads actively endorsed the initiative not only achieved higher compliance rates but also demonstrated greater enthusiasm among staff. This observation confirms the relevance of the WHO’s “institutional safety climate” as a critical component of sustained change, where leadership commitment acts as a multiplier of engagement across all staff levels. Our results are consistent with international literature validating the efficacy of multimodal strategies. For example, Allegranzi and colleagues reported a median increase of 23% in hand hygiene compliance across multiple countries following WHO guideline implementation, while [15] in a meta-analysis, confirmed the superiority of multimodal strategies over single-component interventions. In our study, the greatest improvements were observed among nurses, who started from a higher baseline of adherence compared to physicians. However, the latter group also showed significant post-training gains, suggesting that structured interventions can help reduce compliance gaps across professional categories. These disparities often attributed to workload, risk perception, and differences in clinical culture, can be narrowed with consistent and targeted educational approaches [16].

While the study produced compelling results, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations to properly contextualize the findings. The sample was limited to a single hospital, which may restrict the generalizability of results to other institutions with different resources, staffing models, or organizational cultures. The relatively short follow-up period of six weeks also prevents conclusions about the long-term sustainability of behavioural change. Although multiple monitoring methods were employed-including direct observation, UV fluorescent gel analysis, and electronic dispenser tracking-the potential influence of observer bias and Hawthorne effects cannot be entirely excluded, as healthcare workers may have modified their behaviour simply because they were aware of being observed [17]. The use of electronic systems helped mitigate these effects by allowing for passive and continuous monitoring; however, such tools have their own limitations, particularly their inability to evaluate the correctness of hand hygiene technique. Another significant limitation is the absence of direct clinical outcome data: while literature supports a strong association between improved hand hygiene and reduced healthcare-associated infection (HAI) rates, this study did not include microbiological surveillance or patient-centered endpoints to confirm that correlation in the observed population.

Finally, although the intervention was well received overall, some initial skepticism emerged regarding electronic surveillance. These concerns diminished over time as feedback was anonymized and framed constructively, yet they underscore the need to implement such technologies within a culture of trust, transparency, and nonpunitive learning [18]. Despite these constraints, the study offers meaningful insights and supports the feasibility of structured, multimodal strategies to improve hand hygiene compliance in real-world clinical settings.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the findings have important practical implications. They support the WHO’s assertion that multimodal strategies should be viewed as essential rather than optional in healthcare settings. These strategies are scalable, adaptable to different resource levels, and capable of producing tangible results when applied systematically. Hospitals and healthcare organizations should consider integrating WHO-compliant training into standard operational protocols, utilizing real-time feedback tools-whether via UV demonstrations or electronic sensorsand promoting leadership engagement to reinforce behavioural norms. Institutionalizing hand hygiene performance indicators within quality metrics may further embed these practices into the organizational culture. At a policy level, the Italian National Plan for the Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections (PAICA) offers a useful framework for integrating these strategies at scale, particularly by combining surveillance, staff education, and antimicrobial stewardship. Looking ahead, future research should explore the long-term sustainability of these interventions beyond six months, examine the integration of artificial intelligence for adaptive feedback and predictive compliance modelling, and assess cost-effectiveness across varied hospital settings. Moreover, studies should investigate the direct correlation between improved hand hygiene and specific reductions in HAIs, to further strengthen the evidence base and guide public health policies. Ultimately, this study contributes to the growing consensus that enhancing hand hygiene is not only a moral and clinical imperative, but also a feasible institutional goal-provided it is approached with scientific rigor, strategic planning, and unwavering commitment.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank all healthcare workers that participated to the study.

Ethical Guidelines

Informed consent was waived due to the study’s observational nature and alignment with internal quality improvement practices.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization (2009) WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care is Safer Care. Geneva: WHO Press.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2020) Healthcareassociated Infections.

- Boyce JM, Pittet D (2002) Guideline for hand hygiene in healthcare settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51: 1-45.

- Allegranzi B, Gayet-Ageron A, Damani N, Bengaly L, McLaws ML, et al. (2013) Global implementation of WHO’s multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene: a quasi-experimental study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 13: 843-851.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (2021) Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals 2016-2017.

- Sax H, Allegranzi B, Uçkay I, Larson E, Boyce J, et al. (2007) ‘My five moments for hand hygiene’: a user-centred design approach to understand, train, monitor and report hand hygiene. Journal of Hospital Infection. 67: 9-21.

- Erasmus V, Daha TJ, Brug H, Richardus JH, Behrendt MD, et al. (2010) Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 31: 283–294.

- Pires D, Bellissimo-Rodrigues F, Soule H, Gayet-Ageron A, Pittet D (2017) Hand hygiene with alcohol-based hand rub: how long is long enough? Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 38: 547-552.

- Gould DJ, Moralejo D, Drey N, Chudleigh JH (2017) Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD005186

- Kelly JW, Blackhurst D, McAtee W, Steed C (2016) Electronic hand hygiene monitoring as a tool for reducing health care–associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. American Journal of Infection Control. 44: 956- 7.

- Limper HM, Dallinga RJ, Damen J, Oosterheert JJ (2020) The effectiveness of electronic monitoring of hand hygiene on compliance and hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 104: 361–370.

- Mukerji S, MacIntyre CR, Seale H (2021) Hand hygiene compliance in COVID-19 hospitals: a cross-sectional study of two hospitals in Australia. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. 10:1-9.

- Pincock T, Bernstein P, Warthman S, Holst E (2012) Bundling hand hygiene interventions and measurement to decrease health care– associated infections. American Journal of Infection Control. 40: S18-S27.

- Ministero della Salute (2023) Piano nazionale di prevenzione delle infezioni correlate all’assistenza (PAICA)

- Luangasanatip N, Hongsuwan M, Limmathurotsakul D, Lubell Y, Lee AS, et al. (2015) Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 351:h3728.

- Pessoa-Silva CL, Hugonnet S, Pfister R, Touveneau S, Dharan S, et al. (2005) Reduction of health care-associated infection risk in neonates by successful hand hygiene promotion. Pediatrics. 115: e381-e385.

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Sepulcri D, Dangel M, Widmer AF, Frei R (2018) Educational hand hygiene intervention in a non-outbreak setting: a randomized trial. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 39: 664669.

- Whitby M, McLaws ML, Ross MW (2006) Why healthcare workers don’t wash their hands: a behavioural explanation. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 27: 484-492.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.