Long-Term Clinical Outcomes (24 Months) of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in the Treatment of Chronic Pain - COMFORT RCT

by Mitchell P Engle1, Alexander Hersel2, Genaro Gutierrez3, Vishal Khemlani4, Leonardo Kapural5, Gregory Moore6, Reginald Ajakwe7, Drew Trainor8, Jennifer M Hah9, Peter Staats10, James Makous11, Shilpa Kottalgi12, Patrick Martin12, Mehul J Desai13, John Hatheway14, COMFORT Study Group

1Institute of Precision Pain Medicine, Corpus Christi, TX, USA

2Pain Management and Injury Relief, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

3Pain Specialists of America; Austin, TX, USA

4Columbia Pain Management, Portland, OR, USA

5Center for Clinical Research, Carolinas Pain Institute, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

6Pacific Sports and Spine, Eugene, OR, USA

7Comprehensive Spine & Pain, Burbank, CA, USA

8Denver Spine and Pain Institute, Denver, CO, USA

9Division of Pain Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, USA

10Premier Pain Centers, Shrewsbury, NJ, USA

11Makous Research, LLC, Carlsbad, CA, USA

12Nalu Medical, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA

13International Spine Pain & Performance Center, Washington, DC, USA

14Virginia Mason Franciscan Health, WA, USA

*Corresponding author: Shilpa Kottalgi, Nalu Medical, Inc., 2320 Faraday Ave, Carlsbad, CA 92008, USA

Received Date: 08 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 16 January 2026

Published Date: 20 January 2026

Citation: Engle MP, Hersel A, Gutierrez G, Khemlani V, Kapural L, et al. (2026) Long-Term Clinical Outcomes (24 Months) of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in the Treatment of Chronic Pain - COMFORT RCT. Chron Pain Manag 10: 179. https://doi.org/10.29011/2576-957X.100079

Abstract

Purpose: Few Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) have evaluated Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) for the treatment of chronic pain. Here, we report the 24-month results of the ongoing COMFORT multicenter, post-market RCT evaluating a micro-Implantable Pulse Generator (IPG) system. This device is FDA-cleared for the treatment of chronic peripheral pain. Methods: Eligible subjects were consented and randomized into one of two study arms – the Active Arm received PNS and Conventional Medical Management (CMM), and the Control Arm received CMM, alone. Outcomes were captured in the form of NRS pain scores and functional measures. Subjects who achieved ≥50% pain reduction with the PNS therapy were considered therapy responders. Results: The responder rate at 24 months was 85%, and it was 82% at 18 months. The average pain reduction as compared to baseline pain scores was 67% at 24 months (7.5±1.2 to 2.4±1.7; p<0.001) and 65% at 18 months (7.5±1.2 to 2.6±1.7; p<0.001). All patient-reported outcomes achieved statistical significance. No serious adverse device effects were reported, indicating a strong safety profile. Comfort and ease-of-use outcomes were favorable. Conclusions: The 18- and 24-month results are consistent with the previously reported 12-month outcomes from the COMFORT study. These data demonstrate that PNS therapy, delivered by the micro-IPG, reliably produces significant and durable improvements in net health outcomes.

Keywords: Peripheral nerve stimulation; Chronic pain; Pain management; Implantable neurostimulators; Micro-implantable neurostimulation; Neuropathic pain

Introduction

PNS has been well-researched since the first publication in 1967 [1]. Since then, hundreds of peer-reviewed papers have explored its use and efficacy [2]. As early as 1977, investigators recognized the effectiveness of PNS [3], concluding that “Electrical stimulation for the control of pain is now a well-accepted therapeutic modality… Peripheral nerve stimulators are the most efficacious of the implantable devices [4].” However, it wasn’t until 2016 that results from a well-powered RCT for a permanently implanted PNS device (FDA Product code GZF) were published [10].

To address the need for Level 1 evidence in the field of PNS, the Clinical Study of a Micro-Implantable Pulse Generator FOR the Treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain (COMFORT), was initiated in 2021 [4]. Subjects are being followed for a total of 36 months post-implant and activation. Previously, we reported 3- and 6-month results [11], as well as 12-month outcomes [12]. Here, we report the first long-term 24-month results from this RCT for a permanently implanted PNS device.

Materials and Methods

The COMFORT RCT involved a non-integrated PNS device (Nalu Neurostimulation System, Nalu Medical, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) that obtained FDA clearance in 2019 (K183579 and K191435, FDA product code GZF). The system features a miniaturized IPG (microIPG) powered by an externally worn battery (known as a Therapy Disc) and offers flexible lead configurations to tailor the therapy to each patient’s needs. Implantation involves creating a small pocket for the micro-IPG and tunneling leads from the desired nerve(s) to connect to the micro-IPG. Once the wound is healed, the Therapy Disc is placed over the micro-IPG to provide power for stimulation. Bi-directional communication between the microIPG and Therapy Disc ensures that there is sufficient connectivity and that adequate energy is being delivered. A detailed description of this device is provided elsewhere [13].

The study received Institutional Review Board approval (WCGIRB, Puyallup, WA) and was conducted in compliance with standards of Good Clinical Practice (ISO 14155:2020) as well as applicable local and federal regulations. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05287373; date of submission: 08 February 2022).

The COMFORT study was undertaken at 12 clinical sites in the US with enrolment between 23 February 2022 and 29 March 2023. It was pragmatically designed to mimic real-world clinical care to ensure the data was applicable to clinical practice. Subjects were randomized to either the Active Arm, where they continued CMM plus PNS therapy, or the Control Arm in which they received CMM alone. The therapy was focused on one of 4 anatomical regions: the shoulder, low back, knee or foot/ankle. Complete eligibility criteria are listed on the clinicaltrials.gov website and were previously published [4].

Study subjects were assessed at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18- and 24-months following device activation. The study follow-up was initially up to 12 months and was amended to include a longer follow-up out to 36 months. Validated instruments were used to capture patient reported outcomes (PRO): Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF), Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), EuroQol 5-Dimensions, 5-Levels (EQ 5D 5L), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Complete details of the study design can be found here [4]. Statistical Analysis

Primary endpoint analysis was carried out on the modified-intentto-treat (mITT) population, as pre-specified in the statistical

analysis plan and published here [4]. Missing data were assumed to be at random. Results were reported as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as percentage (count) for categorical variables, unless otherwise noted. Comparisons between baseline and follow-up were conducted by two-sample t-test. P values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. For all outcomes, percent reduction was calculated as a paired analysis within each subject and reported as mean ± SD.

Results

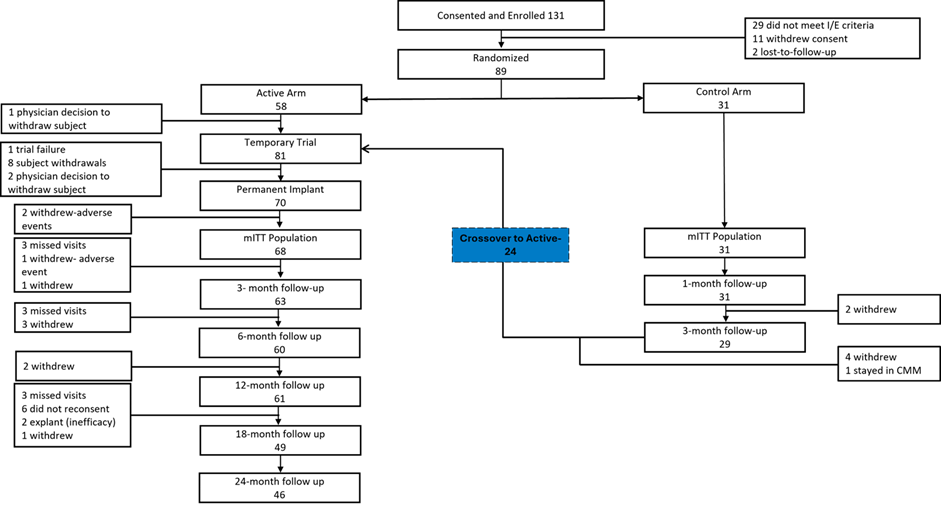

One hundred thirty-one (131) subjects were consented and randomized with 58 subjects assigned to the Active Arm and 31 subjects to the Control Arm (Figure 1). The complete subject disposition is shown in figure 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics are reported here [11]. Notably, subjects initially consented to a 12-month follow-up, which was then extended to 36-months at which point nine subjects exited the study (6 did not reconsent, 1 withdrew and 2 were explanted for inefficacy; figure 1). At 24 months, 49 of the 68 subjects included in the mITT population remained in the study, 3 of which missed this scheduled follow-up visit. The outcomes were reported for the cohort composed of subjects initially randomized to the Active Arm as well as those who crossed over from the Control Arm (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Subject disposition from consent to 24-month follow-up with initial group assignment and Crossover from Control Arm to Active Arm. Note: Subjects who had missed visits were included at next visit.

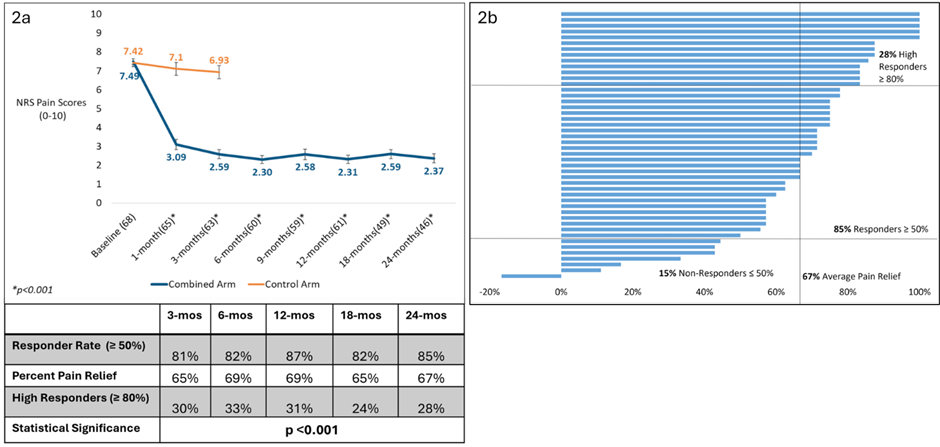

At 18 months, the responder rate (≥50% pain reduction) was 82% (40/49), with an average pain reduction of 65% (p<0.001). At 24 months, the responder rate was 85% (39/46) with an average pain reduction of 67% (p<0.001); 28% of subjects were high responders (≥80% improvement; figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 2: Pain outcomes. a) Mean NRS pain scores (BPI-Q5), responder rates at 50% and 80% criterion and percent pain relief, all as a function of time out to 24 months. Data points represent mean ± SEM, and values in parentheses show the sample size for that time point. Mean percent reduction in pain was statistically significant for each time point compared to baseline (p<0.001). b) Tornado plot showing percent pain reduction for each subject, at 24-months (n=46).

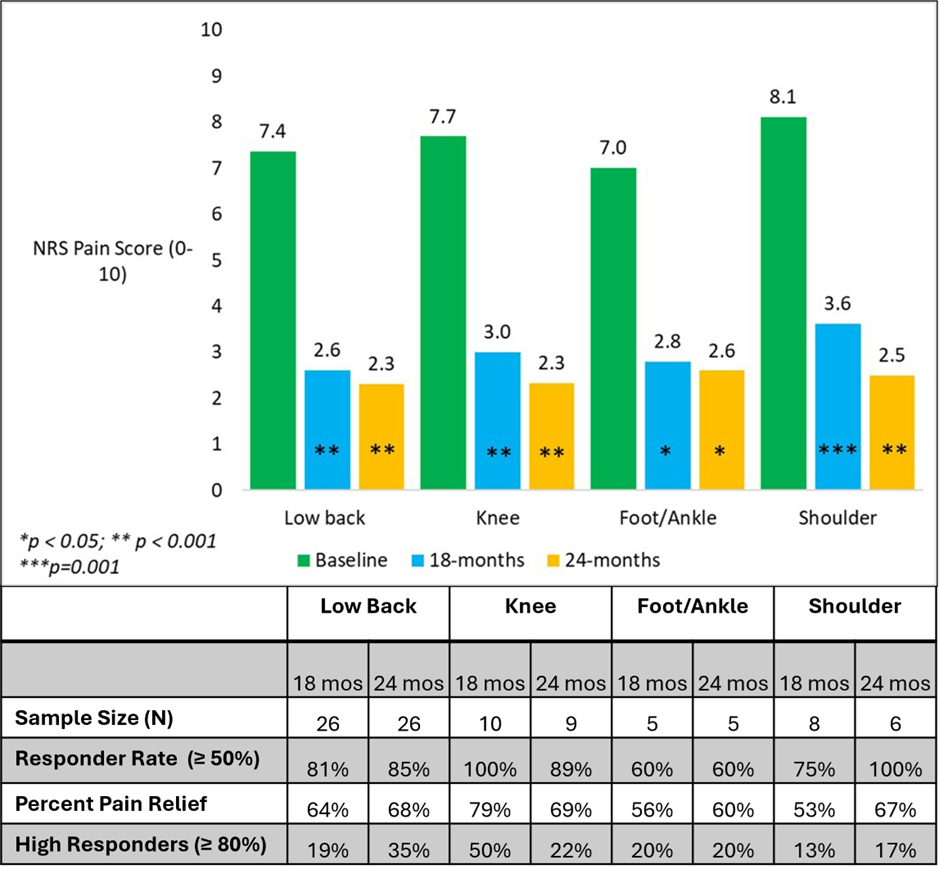

The improvement in responder rates and pain reduction at all follow-up time points were statistically significant for each of the four areas of pain treated (shoulder, low back, knee, foot/ankle). The responder rate for low back was 85% (22/26), 89% (8/9) in the knee, 100% (6/6) in the shoulder and 60% (3/5) in foot/ankle. The average pain relief ranged between 60% and 69% for each of the areas (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Pain relief by area of pain. Mean pain scores at the 18- and 24-month timepoints. The improvement was statistically significant for each area of pain, at both 18 and 24 months, compared to baseline. Responder rates (≥50% and ≥80%) and mean percent pain relief shown.

Secondary endpoints at 18 and 24 months including the ODI, BDI, BPI and EQ-5D-5L, assessments are reported in Table 1. All PROs demonstrated statistical significance at the p<0.001 level when comparing 18 and 24 months to baseline. The established Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID) for each of the PROs was achieved in most of the subjects (Table 1). The MCIDs were chosen and defined based upon the literature as follows: BPI severity [5] (≥ 30%), BPI interference [5] (≥1 point), ODI [6] (≥ 10 points), BDI [7] (≥ 17.5%), EQ-5D-5L [8] (≥ 0.074), PGIC [9] (minimally improved, much improved or very much improved). For this analysis, patients were evaluated for PRO responders based upon MCID.

|

Assessment |

Baseline |

18 months |

24 months |

|

Mean ± SD (N) |

Mean ± SD (N) [Mean % change; p-value] {% subjects achieving MCID} |

||

|

BPI- Severity |

6.82 ± 1.58 (68) |

3.06 ± 2.11 (49) [53%; p<0.001] {71%} |

2.75± 1.86 (46) [57%; p<0.001] {89%} |

|

BPI- Interference |

6.21 ± 2.00 (68) |

2.67 ± 2.26 (49) [57%; p<0.001] {92%} |

2.48 ± 2.58 (46) [55%; p<0.001] {80%} |

|

BDI |

12.90 ± 9.96 (68) |

5.02 ± 6.01 (49) [48%; p<0.001] {69%} |

6.61 ± 7.93 (46) [41%; p<0.001] {67%} |

|

EQ-5D-5L |

0.603 ± 0.15 (68) |

0.777 ± 0.12 (49) [41%; p<0.001] {69%} |

0.785 ± 0.12 (46) [39%; p<0.001] {72%} |

|

ODI |

44.93 ± 13.6 (68) |

26.02 ± 14.1 (49) [40%; p<0.001] {71%} |

24.13 ± 14.2 (46) [44%; p<0.001] {74%} |

Table 1: Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO). Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Quality-of-Life metric (EQ-5D-5L), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

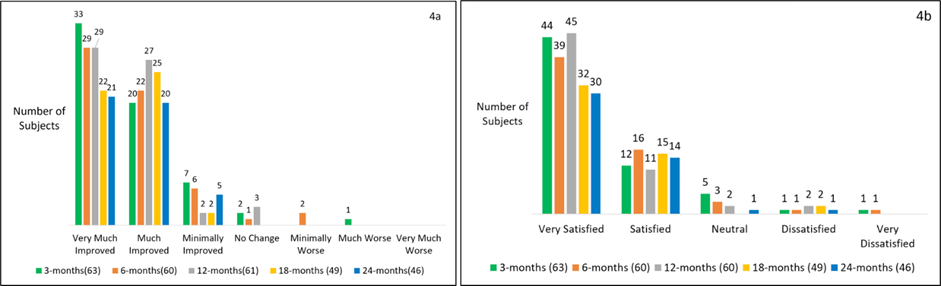

At both 18 and 24 months, 100% of subjects were responders by PGIC (subjects achieving MCID). At 24 months, 46% (21/46) of subjects reported very much improved, 43% (20/46) reported much improved, and 11% (5/46) reported minimally improved; no subjects reported feeling no change, much worse or very much worse at this timepoint (Figure 4a).

There was high patient satisfaction, as well. At 18 months, 96% (47/49) of subjects were either very satisfied or satisfied with the therapy. At 24 months 96% (44/46) of subjects were very satisfied or satisfied (Figure 4b).

Figure 4: Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) and patient satisfaction as a function of time. a) Patient Global Impression of Change at 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24-months showing improvement in over 95% of subjects. b) Patient satisfaction with the micro-IPG system at various timepoints.

At 18 months, 80% (39/49) of subjects continued to find the device comfortable with 82% (40/49) reporting that the device was easy to use. At 24 months, the comfort rating increased to 87% (40/46), and 89% (41/46) of subjects reported that the system was easy to use. All subjects (100%) reported using the device daily.

Protocol compliance was demonstrated by 93% (43/46) of subjects continuing to use one or more forms of CMM at 24 months as follows: oral medications (91%), topical medications (33%), physical therapy (7%), psychological therapy (2%), epidural injections (2%), other treatments (7%) including bracing and heat/ice.

The study maintained an excellent safety record with no reports of Unanticipated Serious Adverse Device Effects (USADE) or Serious Adverse Events (SAE) related to the device and/or procedure. There were no reports of pocket pain. All but 2 non-serious adverse device effects (ADE) were resolved with no sequelae. Of the unresolved events, 1 patient is awaiting a lead revision, and the other patient continues to have skin hypersensitivity that persists. Since the publication of the 12-month results, [12] 3 revisions resulting from IPG migration (1) and lead migration (2) were reported and 5 non-device, non-procedure related SAEs were reported in the combined cohort, all of which have been resolved.

Discussion

This report documents the continuation of statistically significant improvements in net health outcomes at 18 and 24 months following the initiation of PNS treatment with the micro-IPG system. These long-term results compare favourably with outcomes previously reported for the COMFORT RCT at 3-, 6- and 12-months postPNS treatment, confirming the durability of treatment.

These robust results demonstrate the efficacy and safety of the micro-IPG system with statistically significant and durable pain relief at all timepoints, from 3 to 24 months, across multiple anatomical targets. Statistical significance was reached for all patient-reported outcomes, and the long-term safety profile of this study remains strong with no SAEs related to the device or procedure reported to date. The consistent and robust treatment effect demonstrated over 24 months addresses potential concerns about a placebo effect biasing these results.

The current study featured a 7-10-day trial to identify potential therapy responders, which is consistent with standard clinical practice in the US. The trial achieved a 93% responder rate and when combined with the 85% overall responder rate at 24 months, this indicates that false positives affiliated with the temporary trials were minimal.

Pain reduction was also statistically significant across all areas of pain and nerves targeted in this study, indicating that PNS therapy delivered by the micro-IPG is generalizable to use beyond the four areas treated in this study. These results may also indicate that similar Mechanisms of Action (MOAs) described by Strand and Meyer-Friessem are likely responsible for these outcomes.[14,15] These MOAs include the reduction of wide dynamic range neuron activity, reduction of central sensitization, reduction of ectopic peripheral nerve discharge, downregulation of inflammatory mediators and activation of endogenous inhibitory pathways in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

The study also confirms the safety of the micro-IPG system with no reported SAEs related to device or procedure and no reports of pocket pain. In studies with larger IPGs, the frequency of pocket pain was as high as 64% with up to 12% of patients experiencing severe discomfort addressed by additional surgeries [16,17]. The lack of pocket pain with the micro-IPG reduces the need for such extraneous follow-on surgeries and their associated costs. High adherence to device uses and continued CMM further supports these findings and reduces the risk of underestimating safety concerns.

Improvement was seen beyond simple pain scores, with clinically significant improvement in disability, pain interference, pain severity, depression, quality of life and PGIC. PGIC is a validated endpoint that is recommended for use in chronic pain studies by the IMMPACT group [13]. FDA considers PGIC to be an indicator of meaningful outcomes as the result of a treatment. In this study, the self-reported PGIC surpassed the MCID in all subjects at 18 and 24 months. All PROs were statistically superior compared to baseline and 96% of the subjects were very satisfied or satisfied with the therapy. These PROs exceeded both the statistically and clinically meaningful thresholds supporting exceptional efficacy of the therapy alongside the observed pain reductions. Likert scores related to the comfort of the device were also favorable consistent with reports of zero pocket pain. The holistic nature of these successful outcomes indicates that PNS treatment with the micro-IPG system can address the complex clinical needs of chronic pain patients beyond just pain.

The COMFORT RCT addresses a critical gap in PNS research. These results, along with complementary data from COMFORT 2 RCT[18] provide the first level-1 evidence for a permanently implanted PNS device. Similar to the COMFORT RCT, subjects in COMFORT 2 RCT will also be followed out to 36 months, and we look forward to reporting the long-term results from that study as they become available.

Despite the strong historical need for PNS therapy over the last 50 years, there was a lack of RCT data available until COMFORT and COMFORT 2. Previously, Deer, et al. [10] published the only RCT for a permanently implanted lead for PNS. That responder rate was 38% in the Active Arm vs 10% in the Control Arm and pain reduction was 27% in the Active Arm and 2.3% in the Control Arm. COMFORT Active Arm outcomes were statistically significant in terms of both responder rate (85%) and average pain reduction (67%) at 24 months.

Limitations

The study was not double blinded because the therapy is paresthesia based making it challenging to blind. Another limitation was a 3 month Control Arm rather than 6 months or 1 year. A longer Control Arm would be very difficult to enroll given that all of these subjects have a long history of failed CMM (5-years on average) and would violate bioethical standards. Additionally, the consistent and durable outcomes coupled with the large treatment

effect allays concerns about a potential placebo effect. The lack of homogeneity of CMM across all research sites was also a concern. However, the study was not designed to evaluate how various CMMs compare to each other in terms of efficacy. Despite these potential shortcomings, this is the continuation of the COMFORT study and is a significant advancement in the field of PNS.

Conclusions

PNS therapy delivered by a micro-IPG system provided durable and statistically significant improvements in the net health outcomes out to 24 months. These improvements were seen across all endpoints: pain scores, disability, depression, quality of life, global impression of change, satisfaction with the therapy and comfort of the device. The lack of any pocket pain and SADE or SAEs related to the device demonstrated a strong safety profile, which has remained constant over the course of the study. These results indicate that the micro-IPG system provides a viable longterm therapy that can address chronic pain in various areas of the body and maybe pain of various etiologies. The authors will report additional results as they become available.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the COMFORT Study Group and study coordinators at the US sites for their participation and support in this study.

COMFORT Study Group

E. Church1, S. Bainbridge2, Susan Estes2, A. Vellore2, M. Hogue2, N. Patel3, A. Thakral3, R. Kapteyn3, C. Gilmore4, J. North4, J. Priddy-Southern4, E. Liu5, E. Ottestad6, V. Salmasi6, G. Phillips7, R. Vora7, SW. Pierce7, D. Parks7, N. Glass7, J. Peters7, R. Tatevossian8, B. Spiegel9, J. Cohen9, J. Caylor10, M. Arastu10, D. Russo11, T. Rigert11, A. Haroutunian12, P. Lynch13

Affiliations: 1Arizona Pain Specialists, AZ, USA; 2DBPS Research LLC, CO, USA; 3International Spine, Pain & Performance Center, D.C., USA; 4The Center for Clinical Research, NC, USA; 5Institute of Precision Pain Medicine, TX, USA; 6Stanford University, CA, USA; 7Pacific Sports and Spine, OR, USA; 8Comprehensive Spine and Pain Physicians, CA, USA; 9Pain Management and Injury Relief, CA, USA; 10Pain Specialists of America, TX, USA; 11Columbia Pain Management PC, OR, USA; and 12Southern California Orthopedic Institute, CA, USA; 13US Pain Care, AZ, USA.

Ethical Considerations

This study involves human participants and was approved by WCG IRB Tracking Number: 20215749. Participants gave informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr Staats is a consultant for Nalu Medical, Saluda, SPR therapeutics, and Medtronic. He is Chief Medical Officer at electroCore. Shilpa Kottalgi and Patrick Martin are employees at Nalu Medical. James Makous is a consultant at Nalu Medical and owns stock in Nalu Medical. Dr. Hatheway is a speaker and consultant for Nalu Medical. Mehul J. Desai consults for Medtronic and Nalu; receives research support from Abbott, Avanos, Averitas, Mainstay, Nalu, Nature Cell, Saol, SPR Therapeutics, Vivex; and owns stock options in HyperVention, SPR Therapeutics, SynerFuse, and Virdio. Mitchell P. Engle consults for Nalu and Boston Scientific; receives research support from Nalu, Boston Scientific, Nevro, Saluda, SPR Therapeutics, Saol Therapeutics, and Mesoblast.

References

- Wall PD, Sweet WH (1967) Temporary abolition of pain in man. Science 155: 108-109.

- Helm S, Shirsat N, Calodney A, Abd-Elsayed A, Kloth D, et al. (2021) Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness and Safety. Pain Ther 10: 985-1002.

- Long DM (1977) Electrical stimulation for the control of pain. Arch Surg 112: 884-888.

- Hatheway J, Hersel AP, Song J, Engle MP, Gutierrez G, et al. (2024) Design of a Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial for the Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain (COMFORT Study) with a MicroImplantable Pulse Generator. J Pain Res 17: 2891-2901.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, et al. (2008) Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 9: 105121.

- Ostelo RW, de Vet HC (2005) Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 19: 593-607.

- Button KS, Kounali D, Thomas L, Wiles NJ, Peters TJ, et al. (2015) Minimal clinically important difference on the Beck Depression Inventory--II according to the patient’s perspective. Psychol Med 45: 3269-3279.

- Walters SJ, Brazier JE (2005) Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 14: 1523-1532.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, et al. (2005) Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 113: 9-19.

- Deer T, Pope J, Benyamin R, Vallejo R, Friedman A, et al. (2016) Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Partial Crossover Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of the Novel Neuromodulation System in the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Pain of Peripheral Nerve Origin. Neuromodulation 19: 91-100.

- Hatheway J, Hersel A, Song J, Engle M, Gutierrez G, et al. (2025) Clinical study of a micro-implantable pulse generator for the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain: 3-month and 6-month results from the COMFORT-randomised controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 50: 561-567.

- Hatheway J, Hersel A, Engle M, Gutierrez G, Khemlani V, et al. (2024) Clinical study of a micro-implantable pulse generator for the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain: 12-month results from the COMFORTrandomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. rapm-2024-106099.

- Kalia H, Pritzlaff S, Li AH, Ottestad E, Gulati A, et al. (2022) Application of the novel Nalu™ Neurostimulation System for peripheral nerve stimulation. Pain Manag 12: 795-804.

- Strand NH, D’Souza R, Wie C, Covington S, Maita M, et al. (2021) Mechanism of Action of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation. Curr Pain Headache Rep 25: 47.

- Meyer-Frießem CH, Wiegand T, Eitner L, Maier C, Mainka T, et al. (2019) Effects of Spinal Cord and Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Reflected in Sensory Profiles and Endogenous Pain Modulation. Clin J Pain 35: 111-120.

- Burke L, Desai MJ (2024) Pocket pain following spinal cord stimulator generator implantation: A narrative review of this under-reported risk. Pain Pract 24: 659-669.

- Dietvorst S, Decramer T, Lemmens R, Morlion B, Nuttin B, et al. (2017) Pocket Pain and Neuromodulation: Negligible or Neglected? Neuromodulation 20: 600-605.

- Engle M, Gutierrez G, Hersel A, Netzel C, Khemlani V (2025) A Confirmatory Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating a MicroImplantable Pulse Generator for the Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: 3- and 6-Month Results from the COMFORT 2 Study. Chron Pain Manag 9: 171.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.