Human Rights of Residents in the Nursing Home Sector: Developing Practical Evidence-Based Guidance for Implementation

by Elizabeth Morrow*, Shuhua Yang, Marie Carney, Llinos Haf Spencer, Mary Lynch

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI), University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ireland

*Corresponding author: Elizabeth Morrow, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, 123 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, DO2 YN77, Ireland.

Received Date: 15 October, 2025

Accepted Date: 10 November, 2025

Published Date: 13 November, 2025

Citation: Morrow E, Yang S, Carney M, Spencer LH, Lynch M (2025) Human Rights of Residents in the Nursing Home Sector: Developing Practical Evidence-Based Guidance for Implementation. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8: 1680. https://doi.org/10.29011/26889501.101680

Abstract

This study responds to the growing need for practical and implementable nursing home care models that prioritise resident dignity, autonomy, and inclusion. Aim: The study aimed to develop evidence-based guidance to support the implementation of a Human Rights-Based Approach (HRBA) in nursing home care in Ireland. The study was initiated and commissioned by Nursing Homes Ireland and led by the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery at Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) University of Medicine and Health Sciences. Methods: The research study comprised a three-phase methodology: 1) a rapid review of international literature; 2) stakeholder consultations through focus groups; and 3) development of guidance information for nursing homes in Ireland. This paper reports on the third stage of the project, focusing on using a co-design process and best-practice approaches to develop and implement evidence-based guidance tailored for practical use in the Irish nursing home care context. Findings: Findings revealed that while legal and regulatory frameworks exist to protect resident rights, there are significant barriers to their practical implementation. These barriers include institutional routines, staff shortages, inadequate training, and limited resident voice in decision-making. Stakeholders emphasised the importance of moving beyond technocratic compliance with care quality requirements to foster a ‘homeliness culture’ of respect, fairness, and person-led care. Guidance information in the form of accessible information, methods, tools and resources, as well as signposting resources, training and support, was developed drawing on best practice in implementation to facilitate a HRBA in nursing home care settings. Implications for practice: Overall, the guidance information that has been developed aligns with legal and statutory requirements and offers a roadmap for transforming care environments into spaces where human rights are actively protected and promoted. The paper concludes with a call for further research and systemic change to ensure that nursing home care in Ireland fully reflects the values and standards of a human rights-based model.

Keywords: Human rights; Nursing homes; Long term care; Care quality; Dignity; Quality of life.

Background

Despite clear regulatory standards for nursing home care in Ireland and other countries, many residents experience care that limits personal freedom, lacks cultural sensitivity, or neglects individuality. There is a gap between principles of person-centred care and embedding systemic, rights-based care models. FREDA - Fairness, Respect, Equality, Dignity and Autonomy - are the core principles and values which form a rights-based approach and underpin all the articles of the Human Rights Act 1988 [1]. However, these principles may not always translate into practice, for many reasons. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to placing human rights at the centre of nursing home care in Ireland.

A person-centred Human Rights-Based Approach (HRBA) is essential in nursing home care in Ireland because it ensures that residents are not only cared for physically, but also supported in living with dignity, autonomy, and respect. This approach places the individual at the heart of decision-making, recognising their unique preferences, values, and rights. In practice, it means promoting choice, independence, and participation in daily life while safeguarding residents against neglect, abuse, or discrimination. Within the Irish context, where an ageing population and increased demand for long-term care are pressing challenges, a personcentred HRBA provides a framework to align care practices with national standards, ethical obligations, and international human rights principles. By embedding such an approach, nursing homes can move beyond a medical or task-focused model and foster an environment where residents feel valued, empowered, and truly at home.

Over the next 20 years, Ireland’s population aged 65-84 is projected to grow by 65%, while the number of people aged 85 and over is expected to double [2]. Reaching an average life expectancy of 83 years represents a significant national achievement. However, these demographic shifts also bring challenges - particularly in sustaining the workforce and ensuring adequate capacity to deliver high-quality, long-term care for older adults. As people live longer, many are managing multiple chronic or life-limiting conditions that often require support for self-management, specialist care, and integrated care solutions [3].

The research objective was to explore how a HRBA can be integrated into nursing home care in Ireland, enhancing the dignity, autonomy, and well-being of residents. In this three-phase study, a rapid review of international literature found that dignity in care is influenced by institutional culture, funding, staffing, and training [4]. A subsequent phase of key stakeholder consultations, using focus group methods and content analysis [5], confirmed the need for systemic reform to protect the rights of residents beyond checkbox compliance. Phase 3 of the study aimed to build on these findings and to draw on best practice in implementation, to develop HRBA guidance information for diverse nursing home care provider organisations in Ireland.

Materials and methods

Study design

Overall, the study applied a mixed-methods design conducted in three phases. Phase 1 was a review of international literature on human rights in nursing homes globally. The aim was to examine the evidence about existing systems, or models of upholding human rights in nursing homes or residential care homes globally [4]. The main question for Phase 1 was ‘What is the evidence about contemporary systems and good governance approaches to human rights adherence for nursing/residential care home residents globally?’ [4]. Phase 2 was the consultation process, through focus group interviews with key stakeholders in the older person’s human rights in nursing homes in Ireland [5]. The research questions were: 1) what human rights in nursing homes look like for those using it; 2) how human rights integration and implementation in nursing homes may be achieved; and 3) what cultural and social dynamics influence human rights in nursing homes? Phase 3 aimed to synthesise evidence from Phases 1 and 2 to produce a comprehensive guidance document tailored to the Irish nursing home sector. The guidance aimed to operationalise human rights principles into actionable strategies, tools, and examples for providers, managers, and staff.

Data collection

Phase 1 (Rapid review): Literature was systematically sourced from five databases (PubMed (including MEDLINE); EMBASE; CINAHL; PsycINFO; Social Sciences Citation Index; Web of Science, and relevant grey literature). Search terms combined concepts of nursing homes/residential care, older persons, and human rights/human rights-based approaches. Papers were included for screening if they reported on human rights-related outcomes in nursing homes, including dignity, equity, respect, and economic impact/benefits, and were published in English, between January 2004 to August 2024. The systematic review management platform ‘Covidence’ [6] was used in the screening process. Two independent reviewers screened the literature. In the case of a conflict raised, the research team reviewed the literature together to resolve any conflicts. Data were extracted based on eligibility criteria, which are outlined in the published literature [4].

Phase 2 (Stakeholder consultations): Focus group participants (n = 29) were recruited through Nursing Homes Ireland (NHI) to ensure a representative cross-section of stakeholders. Participants included were from advocacy and representative groups, voluntary organisations, statutory and independent providers, government agencies and professionals involved in caring for older residents in nursing homes and social care services. Five semi-structured focus group interviews were held online via Microsoft Teams in February 2025. Two researchers facilitated the interviews, following a topic guide informed by the evidence from Phase 1 rapid review [4]. The focus group sessions were recorded on Microsoft Teams and transcribed by a third-party transcription service. Content analysis approach was applied to identify the themes generated from the focus group interviews [7].

Phase 3 (Guidance development): A first draft of the guidance was developed by the lead author and circulated to the coauthors for comment and critique, before seeking input on sector knowledge and practice development expertise from the research commissioners (Nursing Homes Ireland). The development process included drawing together findings from Phases 1 and 2 and utilising structured searches of existing HRBA methods and tools. Draft recommendations were considered against the FREDA principles (Fairness, Respect, Equality, Dignity, Autonomy) [1] and enhanced with tools for implementation, such as training resources, reflective practice models, and communication strategies. These recommendations were refined through iterative discussion, ensuring alignment with existing Irish legal and regulatory frameworks, including the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015 [8], and HIQA National Standards for Residential Care [9]. The final guidance document included specific sections for providers/managers, staff, and practical tools and resources [10].

Analysis to develop the guidance information

Building on the findings of the rapid review of the literature (Phase 1) as well as the findings of the stakeholder consultation (Phase 2) previously reported, a further higher-level analysis was undertaken to a) draw out key points and evidence from the literature to include in the guidance information and b) to contextualise the information in relation to the Irish context, issues and challenges. This higher-level analysis, described in detail below, resulted in a draft prototype guidance information document. This draft document proposed a set of actionable strategies to place a HRBA at the heart of nursing home care in Ireland. Formulation of the guidance included embedding FREDA principles [1], enhancing communication and consent practices, promoting inclusive staffing and cultural competence, and supporting positive risk-taking. Practical tools such as scenario-based learning, team debriefs, Schwartz Rounds [11], and person-centred care planning are also highlighted within the final guidance information, with examples [10].

Drawing on implementation best practice

The stakeholder consultations revealed that effective implementation of guidelines in nursing homes requires more than simply disseminating information; it involves embedding evidencebased practices within organisational culture, staff routines, and resident care. Furthermore, implementation science confirms that successful uptake depends on three interrelated factors: a) the content of the guidelines, b) the context of the organisation, and c) the processes used to introduce and sustain change. Best practice emphasises a person-centred and participatory approach, ensuring that all staff are engaged in the development, adaptation, and application of guidelines in healthcare settings. This fosters ownership and reduces resistance to change. In nursing home settings, where multidisciplinary teams work closely with residents and families, collaboration and open communication are particularly critical.

Theories such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) developed by Laura Damschroder and colleagues, suggest that alignment between guidelines and existing organisational priorities, leadership support, and resource allocation strongly influence sustainability [12]. Similarly, the PARiHS framework (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) originally developed in the late 1990s by a team led by Alison Kitson, along with Gill Harvey and Brendan McCormack, underscores the importance of evidence, context, and facilitation [13-14]. In practice, this meant that the guidance information should not only be evidence-based, but also practical, adaptable to local conditions, and supported by links to effective training and leadership in HRBA. Thus, these principles of participation, engagement and practical application, were incorporated into the guidance information produced [10].

Results

The results briefly present the findings of the first two phases of the study, followed by a more detailed presentation of the results of the phase three guidelines development process.

Summary of key findings from the rapid review

After removing duplication, n = 12,068 literature were screened based on title, abstract and full text for eligibility. Finally, the rapid review identified 86 relevant studies, including review/systematic reviews (n = 31); cross-sectional study/case study/mixed-method study (n = 11); Qualitative study (n = 25); Quantitative study (cohort/survey) (n = 15); and randomised controlled trials (n = 4).

The studies were thematically grouped in nine themes: Autonomy, Freedom of movement, Dignity, Quality of life, Restraint, Spirituality, Sexual expression, Elder abuse, and Elder care. Across these themes, the review highlighted the central importance of adopting a HRBA underpinned by the FREDA principles [1]. Interventions promoting autonomy, such as negotiated care planning, supported decision-making, and advocacy mechanisms, were linked to higher resident satisfaction and well-being [4]. Dignity and respect were consistently identified as fundamental to residents’ quality of life. However, systemic barriers were reported, including institutional routines that prioritised efficiency over individual choice, workforce shortages, lack of training in human rights, and a compliance-focused regulatory culture [4]. Evidence also showed under-researched areas, such as sexuality and spiritual expression, where the rights of residents were often neglected.

Summary of key findings from stakeholder consultation

The stakeholder consultations, using focus group methodology, provided rich qualitative insights that both reinforced and contextualised the findings of the rapid review. The findings were grouped into six main themes, which are described in detail in the work published by Carney et al. [2]. Briefly, the identified themes included Centrality of Person-Centred Care, Regulation and Compliance, Family Involvement and Communication, Culture and Ethos, Challenges for Organisational Development, Economic Challenges and Resource Limitations, and Depravation of Liberty and Managerial Challenges.

Participants in the consultation focus groups emphasised the right of residents to make their own choices, even when these choices involve risk, and they criticised overly paternalistic or restrictive practices. Workforce shortages, economic constraints, regulatory pressures, and a “culture of blame”, were frequently cited as barriers to rights-based care. Families were seen as both essential advocates for residents and, at times, sources of tension when their views conflicted with resident preferences. In addition, a strong call emerged for cultural change, shifting from a medicalised or compliance-driven model to one that is relational, homely, and genuinely person-centred. In terms of education and training, participants consistently highlighted the need for ongoing education on human rights. The Assisted Decision-Making Act [5] argues that regulation alone cannot achieve meaningful change. Issues relating to cultural competence, religious needs, and the rights of residents to intimacy and sexuality were raised as underacknowledged but vital aspects of rights-based care.

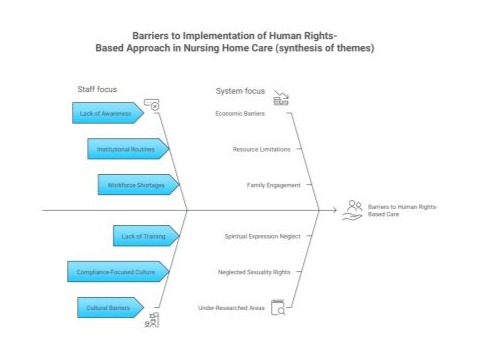

Figure 1 illustrates the synthesis of themes from phase 1 and 2 findings [4,5]. It highlight the potential barriers to implementation of a HRBA in nursing home care. Equipped with this insight into potential barriers to implementation, the development of the guidance information document was informed by a systematic and iterative process co-designed to ensure both theoretical robustness and practical applicability, described below.

Figure 1: Barriers to implementation of human rights-based approach in nursing home care (Synthesis of themes). Source: Figure based on Phases 1 and 2 of the Nursing Homes Ireland three phase human rights project.

Phase 3: Translating evidence into implementable guidance information

In Phase 3 of the study evidence generated in Phases 1 and 2 was synthesised by the lead author (EM) and translated into prototype draft guidance. The draft was reviewed and refined by the wider research team (MC, ML, SY and LHS) with discussion and input from Nursing Homes Ireland who contributed sector awareness, policy perspectives and practice development expertise. Discussions and decision-making focused on the key considerations summarised below. The overall co-design process was underpinned by established implementation science frameworks, particularly the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the PARiHS framework, which emphasise the importance of incorporating evidence, attention to context, and facilitation of accessibility and usage in translating knowledge into practice.

Key points of discussion and decision making regarding the HRBA guidance included:

- Identification of target audiences and their needs, to maximise relevance of the guidance for frontline staff, management, Persons in Charge (PIC) and other staff groups.

- Alignment with legal and regulatory frameworks to ensure compliance with existing standards.

- Integration of human rights values, specifically the FREDA principles (Fairness, Respect, Equality, Dignity, and Autonomy), to embed a rights-based approach within the guidance.

- Terminology precision, with attention to definitions and language, to minimise ambiguity and promote consistency in application.

- Tiered structuring of recommendations to allow incremental progress across organisations with differing levels of capacity.

- Practical presentation format that recognised the central role of staff in care delivery, while balancing organisational requirements with human rights considerations.

- Incorporation of established, evidence-based methods and tools, supplemented with case studies and scenarios to contextualise recommendations and facilitate real-world application.

- Use of scenarios and case studies for learning about HRBA and strategies for positive risk taking with resident engagement and consent.

- Provision of signposting to additional resources to support extended learning and sustain implementation across diverse nursing home settings.

Through a structured co-design process, the evidence base (Phase 1) and stakeholder consultation findings (Phase 2) were systematically distilled into actionable and context-sensitive guidance. The iterative refinement of content material over three months (the timeline was March to June, with the launch in July) involving both research team (FNM) and sector knowledge, policy expertise and practice development insights (NHI), strengthened the validity, usability, and accessibility of the final document.

Identification of target audiences and guidance needs:

Building on the international evidence from the Phase 1 rapid review, and perspectives from key stakeholders from Phase 2, the guidance was designed to provide information on practical tools and resources for different groups of staff working in the sector in Ireland. Thus, the guidance information was developed targeting nursing home care providers, Persons In Charge (PICs), managers, and frontline staff working in nursing homes. This required structuring the guidance into different parts, to meet the information needs of these different target audiences. In line with the PARiHS framework, the guidance was developed by integrating robust evidence, careful attention to organisational context, and structured facilitation strategies. Analysis of the guidance framework identified four interrelated domains essential to embedding a rights-based approach within nursing homes, which were used to develop four parts to the guidance information document [10].

At the managerial and provider level, data highlighted the importance of integrating human rights principles into organisational policies, ensuring clarity in communication and complaints systems, supporting staff education in ethics, and fostering safe, inclusive workplaces through active engagement with residents, families, and advocacy organisations. These measures were viewed as central to building a sustainable rightsfocused culture.

At the staff level, findings emphasised the operationalisation of dignity and autonomy through practices such as the use of preferred names, offering choices, obtaining consent, recognising cultural, dietary, spiritual, gender and sexuality needs, reporting abuse or neglect, balancing safety and freedom, and respecting end-of-life wishes in collaboration with families.

A range of practical methods were also identified as mechanisms for implementation, including structured daily handovers, care plan reviews, resident and family meetings, positive risk-taking discussions, scenario-based learning exercises, and the use of audits and feedback systems to monitor progress.

Finally, participants consistently pointed to external sources of support, such as HIQA, Age Action, Sage Advocacy, WHO QualityRights, and NHI/RCSI training, as critical resources to sustain and extend best practice. Hence, references to support were integrated into the guidance document.

Learning from the findings of the stakeholder consultations, the guidance (phase 3 of the NHI human rights project) was structured around four parts:

Part 1 of the guidance document was designed to provide human rights information for nursing home providers, PICs, and managers in nursing homes. It includes information and sources of support to: Integrate human rights into policies and practices; Ensure clear communication and complaint handling; Implement human rights education and promote an inclusive and safe working environment; Engage residents, families, and advocacy groups.

Part 2 provides information to support nursing home staff, including: Respect for resident autonomy and dignity; Recognise and report signs of abuse or neglect; Ensure clear communication and informed consent; Promote inclusivity, equity and person-led support; Balance safety with freedom and privacy; Support endof-life choices with compassion.

Part 3 summarises the methods and tools that are accessible for relevant stakeholders to improve understanding of HRBA, reviewing their practice or implementing improvements. These tools were designed to be flexible and adaptable, encouraging nursing homes to embed a rights-based ethos within their organisational culture. Part 4,

Part 4 consolidates key regulatory, conceptual, and educational resources to support a human rights-based approach in Irish nursing homes. Central instruments include the Health Act 2007 [15], the Patient Safety Act 2023 [16], and HIQA’s National Standards (2016) [9], with accompanying human rights guidance [17]. Broader perspectives are provided by voluntary and community organisations in Ireland such as Age Action Ireland, Sage Advocacy, and the Care Champions/Irish Centre for Human Rights, all of which highlight systemic rights concerns in residential care. Training resources such as NHI programmes, academic micro-credentials, Schwartz Rounds [11], and WHO QualityRights are cited in the guidance. Collectively, these sources provide a layered evidence base combining regulation, advocacy, and professional education to embed and sustain a rights-focused culture in practice.

Alignment with legal and regulatory frameworks:

The protection of human rights in nursing homes in Ireland is underpinned by an existing comprehensive legal and regulatory framework, which the guidance information presents in an accessible format. The Irish Constitution (1937) [8] establishes fundamental rights to dignity, equality, and personal freedom. The human rights principles were further enforced by international agreements such as European Convention on Human Rights [18] (incorporated into Irish law in 2003) and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ratified in 2018) [19]. National legislation further strengthens these protections: the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act (2015) [8] supports residents’ involvement in decisions about their lives; the Equal Status Acts (2000–2015) [20] prohibit discrimination in service provision; and section 42 of the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Act (2014) [21] obliges public bodies to promote equality and safeguard rights in their daily work. Specific to healthcare, the Health Act (2007) provides the statutory basis for nursing home regulation and established the HIQA, which sets and monitors standards of care. Complementing these measures, HIQA’s National Standards for Residential Care Settings for Older People in Ireland (2016) [9] operationalise legal principles in practice, ensuring that residents’ dignity, privacy, choice, and rights remain central to everyday care.

Integration of human rights principles:

In accordance with the core principles of human rights, the FREDA principles advocated by HIQA [17], the co-design of the guidance information content material emphasised fairness, respect, equality, dignity and autonomy and illustrated these concepts visually for alternative ways to access the information. The resulting guidance information document makes it clear that human rights-based approach in the context of nursing homes involves fostering a safe, inclusive, and person-centred environment that promotes the wellbeing of residents and quality of life [10]. It requires building a shared understanding of care values and human rights among staff and residents.

Terminology precision:

Using plain language, avoiding technical or jargonistic terms, when discussing human rights is essential to ensure accessibility, understanding, and relevance for all staff working in nursing homes. Complex or overly legalistic language can create barriers and discourage engagement, whereas clear and straightforward wording helps staff to connect human rights principles directly with their daily practice. Positive framing, incudes the protection of rights and promotion of care quality, rather than overly framing rights in terms of litigation or compliance narratives. To make the principles more understandable, such as reducing use of restraints, the language throughout the guidance is carefully reviewed for clarity, consistency, and cultural inclusivity. This includes attention to the choice of person names, case examples, and scenarios to ensure they are representative, respectful, and meaningful in the Irish nursing home context. Providing clear definitions of key terms further supports shared understanding, enabling staff, residents, and families to interpret and apply human rights concepts with confidence. By focusing on inclusive and practical terminology, the guidance supports the integration of a HRBA into everyday care, in a way that is both relatable and actionable.

Tiered structuring of recommendations:

In the Irish nursing home context, a tiered guidance framework with levels that include Starting Out, Progressing, and Advancing, offers a practical and scalable approach to quality improvement. This structure recognises that nursing homes operate with varying resources and levels of expertise, allowing facilities to engage with guidance at a stage appropriate to their current capacity. At the Starting Out level, emphasis is placed on embedding essential, foundational practices to ensure safety and consistency of care. The Progressing stage supports the development of more structured systems, such as outcome monitoring, staff development, and the refinement of care processes. At the Advancing stage, homes move towards leadership in best practice, innovation, and continuous quality improvement. Such a graduated framework not only aligns with regulatory expectations in Ireland but also fosters staff confidence, encourages organisational learning, and enhances resident-centred care through steady, evidence-informed development.

Practical presentation format:

The guidance is designed in a practical format to maximise accessibility, sense making, and ease of use. A digital version is available to support wide and cost-effective distribution, ensuring that nursing homes and staff can access the document quickly and conveniently. The document is concise, kept to under 20 pages, so that it remains focused, manageable, and suitable for everyday reference. It is also formatted for printing in greyscale to reduce costs and increase usability across different settings. To complement the main guidance, a one-page leaflet summarising the key messages was produced, providing an at-a-glance resource that can be displayed in staff areas or used as a prompt during training and team discussions.

Respectful recognition of staff human rights:

Stakeholders in the consultations discussed the role of care cultures and respect for everyone’s human rights. Thus, the guidance information framing was intentionally designed to recognise that staff in nursing homes also have human rights, including the right to a safe and respectful workplace. In Ireland, protections are provided through the HSE’s Dignity at Work Policy [22], employment legislation overseen by the National Employment Rights Authority (NERA), and health and safety guidance from the Health and Safety Authority (HSA). HIQA further promotes a HRBA that upholds dignity, respect, and equality for staff, and encourages their involvement in shaping their work environment [23].

Incorporation of established, evidence-based methods and tools:

Human rights-based methods and tools in residential care are well established in the literature as effective approaches to promoting dignity, autonomy, and safety while fostering a culture of accountability and continuous improvement. Practices such as daily handovers, staff supervision, and performance appraisals are widely recognised as mechanisms to ensure continuity of care and embed human rights principles in everyday practice. Regular resident care plan reviews and structured meetings with residents and families are consistently highlighted for their role in supporting participatory decision-making and maintaining responsiveness to individual needs. Reflective practices, including positive risk-taking discussions [24], Schwartz Rounds [11], and team debriefs [25], are similarly well documented as means of enhancing empathy, critical self-awareness, and collective professional learning, especially during times of additional stressors such as the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, systematic quality assurance processes, such as audits, external inspections, and self-assessments, are firmly established in research and policy as essential for monitoring compliance, driving service improvements, and safeguarding human rights in care settings . Thus, the guidance information summarises existing approaches to make them more accessible to nursing home staff and raise awareness of their availability for training and development purposes.

Use of scenarios and case studies for learning:

The research literature shows that a scenario-based approach to learning can make reflection on human rights issues more thought provoking, accessible and engaging for staff in the nursing home sector, and this was reenforced by the experiences of NHI’s close relationship with nursing homes. Case examples, such as how to respond to out-seeking behaviours, allow teams to focus on particular challenges within the nursing home setting, or on issues raised directly by staff themselves. Thus, the guidance information provides case studies that allow staff to consider how human rights, and their protection and promotion, might be experienced from the perspective of colleagues and residents. Thinking differently about risk management and safety is a central component of advancing HRBA. To maintain conciseness of the document, the information signposts that further HRBA scenarios relating to dementia, Alzheimer’s, and mental health can be found in HIQA guidance [17].

Provision of signposting to additional resources:

The consultation revealed that nursing home staff may not know where to access information about HRBA without having to undertake their own searches online to gain new knowledge or further explore issues. Thus, the guidance document also provides signposting to sources of information and support for HRBA, key organisations and a list of relevant and reliable sources where staff can find out more [10].

Discussion

In this study of HRBA, effective implementation of human rights principles in nursing home care, sought to transform guidelines from static documents into living tools that can actively shape daily practice, improve resident outcomes, and promote a culture of continuous learning and human rights-based care. Our findings extend the application of the PARiHS [14] and CFIR [12] frameworks by showing that contextual sensitivity, as emphasised in the PARiHS focus on context, and working in partnership, resonating with CFIR’s emphasis on engagement and collaboration, are key issues for ensuring effective and sustainable implementation in nursing home settings.

Figure 2 draws together the learning from the co-design process highlighting the key considerations that were made. These steps could be followed again in the future, refined and tested with stakeholders to ensure that evidence and best practice in implementation is translated into HRBA in nursing home settings.

Figure 2: Illustration of the collaborative development steps from source data through to implementable guidance information in the nursing home care context.

An important discussion point emerging from the guidance development process is the need to balance the rights of residents and staff through a HRBA, recognising both groups as rightsholders. Practically, this entails implementing risk assessments that identify hazards while avoiding unnecessary restrictions on the autonomy of residents, and promoting shared decisionmaking that actively involves residents and, where appropriate, their families in discussions about care choices. Both phase 1 and phase 2 showed that staff training and support are critical, hence guidance needs to be reinforced by equipping personnel with skills in ethical reasoning, de-escalation, and person-centred care to manage complex situations effectively. Additionally, clear policies and communication protocols are necessary to safeguard staff rights while respecting residents’ autonomy, making both sets of rights explicit in everyday practice. Finally, continuous review mechanisms should be in place to monitor outcomes, ensuring that neither resident independence nor staff wellbeing is consistently compromised.

A further key point is that facilitated discussions among staff can help raise awareness and translate the FREDA principles into nursing home care practice. The guidance information document therefore suggests topics for positive risk-taking discussions, including: What does “positive risk-taking” mean in the context of the nursing home? How do we assess risks without automatically saying “no” to a resident’s choice? How can positive risk-taking contribute to a resident’s health, wellbeing and quality of life? How should we respond if a positive risk does not turn out well, to avoid blame whilst promoting freedom and autonomy? These essential questions can form the basis for workplace training and HRBA practice development.

For human-rights discussions to be effective, they should be conducted in a safe and respectful environment, guided by clear objectives, and supported by scenarios and case examples rather than reference to individual residents. The guidance thus incorporates best practice for running HRBA discussions as follows: Set a clear purpose for the discussion; Create a respectful, safe space; Use examples or case studies rather than discussing real people; Encourage all voices to have a say, not just the loudest; Focus on practical solutions, not just ideal situations; Keep the rights of residents at the centre of care and decisions; Summarise key points along the way; Agree any next steps if needed; Stick to time limits and end on a positive note.

As a result, the guidance information is not just a written documentthe tiers recommendations and suggested actions promote allocation of dedicated time within a supportive environment, to reflect on challenging situations and explore potential solutions [6]. The evidence shows that these structured opportunities will contribute to professional growth by strengthening knowledge and skills related to human rights in care. A discursive approach, that allows for interaction and questions, could also help to build confidence in applying rights-based principles, ensuring that staff are better prepared to uphold the dignity and autonomy of residents while reducing the likelihood of unintentional rights infringements. Embedding guidelines into existing quality assurance processes, staff training programmes, and regulatory frameworks (such as HIQA standards in Ireland) strengthens accountability and ensures consistent practice.

A limitation of this study - and an opportunity for future research - is to evaluate nursing home provider responses to the guidance. Implementation best practice also involves adaption and feedback mechanisms, allowing staff to identify barriers, share successes, and continuously improve care through a HRBA. Informal follow up could be strengthened with a robust evaluation of actions taken to implement a HRBA in a sample of nursing homes.

Conclusion

This novel project used phased approaches to review the current evidence, which informed engagement strategies to gain insights from key stakeholders across the sector around the human rights of residents in nursing home care. The results emphasise that a human rights-based approach is essential for quality of care and quality of life for residents receiving nursing home care and the importance of staff education, strong leadership, and systemic reform to support homely, culturally respectful, and personalised care. The guidance information was officially launched to an audience of over 40 delegates by Elaine Cassidy, Director General of the Office of the Ombudsman, in Dublin in August 2025. By combining NHI’s policy leadership with RCSI’s research expertise, this study provides a foundation for further work to place a human rights-based approach at the heart of nursing home care in Ireland.

Acknowledgements

This research study was initiated and funded by Nursing Homes Ireland (NHI), whose leadership, guidance and strategic direction were central to its development. Commissioners of the study were Tadhg Daly, Chief Executive Officer, and Deirdre Shanagher, Strategic Clinical Nurse Expert with Regulatory Compliance. The project stems from NHI’s HOMES strategy, which places the voice and rights of nursing home residents at its core. The collaborative partnership between NHI and the FNM at RCSI was essential to bringing this important work to fruition.

Ethical approval

Approval to undertake focus groups and transmission and analysis of recorded data was obtained from the Ethics committee of RCSI.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Curtice MJ, Exworthy T (2010) FREDA: a human rights-based approach to healthcare. Psychiatrist 34: 150-156.

- Central Statistics Office. Older Persons Information Hub 2024.

- Larkin J, Walsh B, Moriarty F, Clyne B, et al. (2022) What is the impact of multimorbidity on out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland? A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12: e060502.

- Spencer LH, Carney M, Yang S, Lynch M (2025) Human Rights of Residents in the Nursing Home Sector: A Rapid Review of the Evidence. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8: 1616.

- Carney M, Yang S, Spencer LH, Morrow E, Lynch M (2025) Human Rights for Older Residents in Nursing Home Care in Ireland: Consultation, Perceptions and Insights. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8: 1651.

- Covidence systematic review software (2025)Veritas Health Innovation Melbourne Australia.

- Krippendorff K (2022) Content analysis an introduction to its methodology.

- Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015.

- National Standards for Residential Care Settings for Older People in Ireland. Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA); 2016.

- Morrow E, Spencer LH, Carney M, Yang S, Lynch M (2025) Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, RCSI. Placing human rights at the heart of nursing home care in Ireland. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland p: 1701980 Bytes.

- Pepper JR, Jaggar SI, Mason MJ, Finney SJ, Dusmet M (2012) Schwartz Rounds: reviving compassion in modern healthcare. J R Soc Med 105: 94-95.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, et al. (2009) Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci 4: 50.

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B (1998) Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care 7: 149-158.

- Bergström A, Ehrenberg A, Eldh AC, Graham ID, Gustafsson K, et al. (2020) The use of the PARIHS framework in implementation research and practice—a citation analysis of the literature. Implementation Sci 15: 68.

- Health Act 2007.

- Patient Safety (Notifiable Incidents and Open Disclosure) Act 2023.

- Guidance on a human rights-based approach in health and social care services.

- European Convention on Human Rights.

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- Equal Status Acts 2000-2015.

- Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Act 2014.

- Dignity at Work Policy for the Public Health Service (Revised 2022).

- HIQA. Overview of HIQA regulation of social care and healthcare services 2017.

- Foundas M (2025) Dignity of risk in residential aged care: a call to reframe understandings of risk. Medical Journal of Australia 223: 186188.

- Perri GA, Lewin WH, Khosravani H (2021) Team debriefs during the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care homes: Essential elements. Can Fam Physician 67: 908-910.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.