HPA Axis Balancing in Psoriasis Patients – Hair Cortisol, HRV Improvement – with an Interventional Stress Management Program “Pythagorean Self-Awareness”

by Bekoulis V1#, Mykoniatis M1#, Nicolaidou E2, Chrousos G1,3, Charalampopoulou M1,4, Papadopoulou A1, Pipelias P1*, Vavouli C2, Roboti N2, Darviri C1

1Postgraduate Course “Science of Stress and Health Promotion”, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

2First Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, “A. Syggros” Hospital for Skin and Venereal Diseases

3University Research Institute of Maternal and Child Health and Precision Medicine, and UNESCO Chair on Adolescent Health Care, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Aghia Sophia Children’s Hospital, Athens, Greece

4First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Hippokration Hospital, Medical School, Athens, Greece

#Contributed equally

*Corresponding author: Pipelias P, Postgraduate Course “Science of Stress and Health Promotion”, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Received Date: 10 February, 2026

Accepted Date: 17 February, 2026

Published Date: 20 February, 2026

Citation: Bekoulis V, Mykoniatis M, Nicolaidou E, Chrousos G, Charalampopoulou M, et al. (2026) HPA Axis Balancing in Psoriasis Patients – Hair Cortisol, HRV Improvement – with an Interventional Stress Management Program “Pythagorean Self-Awareness”. J Community Med Public Health 10: 555. DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100555

Abstract

Background: Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease that is strongly associated with psychological stress. Dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and alterations in cortisol secretion have been implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis and in the burden experienced by affected patients. Objective: This study aimed to examine the impact of Pythagorean Self Awareness Intervention (PSAI) on perceived stress, sleep quality, cognitive function, quality of life, and hair cortisol levels in patients with psoriasis. Methods: Twenty-one adults with clinically diagnosed psoriasis (47.6% male, 52.4% female), all receiving stable biologic therapy, participated in a six-week intervention program based on the PSAI. Participants underwent repeated assessments before and after the intervention, including validated self-report questionnaires evaluating psychological and lifestyle-related parameters, as well as hair cortisol concentrations as a biomarker of long-term HPA axis activity. Changes across measurement time points were analyzed using paired statistical tests. Results: Following the intervention, participants exhibited reductions in perceived stress and improvements in sleep quality, cognitive function, and self-reported lifestyle behaviors. Additionally, a statistically significant increase in hair cortisol levels was observed, suggesting a potential modulation of stress-related biological activity. Given the absence of a control group and the small sample size, findings should be interpreted as preliminary. Conclusion: The results of this pilot study suggest that holistic stress management interventions such as PSAI may have beneficial effects on psychosocial outcomes and stress-related biomarkers in patients with psoriasis. These findings support the feasibility of integrating holistic stress management approaches as adjunctive strategies in psoriasis care. Larger, controlled studies are warranted to confirm these observations and to further explore underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: Psoriasis; STRESS management; Pythagorean selfawareness; PSAI; Perceived stress; Sleep quality; Cognitive function; Hair cortisol; HPA axis; HRV

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease affecting approximately 2% of the global population [1,2]. Although it may occur at any age, psoriasis most commonly manifests during early adulthood (15-20 years) and later in life (55-60 years) [3]. Plaque psoriasis represents the predominant clinical phenotype, accounting for the majority of cases [3], while disease prevalence appears to be comparable between males and females [4].

Beyond its physical manifestations, psoriasis is associated with stress and substantial psychosocial burden. Visible skin lesions frequently lead to stigmatization, social exclusion, diminished self-esteem, and increased vulnerability to negative emotional states, including psychological distress [5]. These psychosocial challenges, combined with chronic physical symptoms, significantly impair the quality of life of psoriatic patients. Moreover, psoriasis has been linked to increased neurological and cognitive morbidity, including deficits in working memory and reduced cognitive performance [6-9]. Accumulating evidence further suggests that patients with psoriasis exhibit elevated rates of depressive symptoms and anxiety disorders [10,11]. These psychological comorbidities are thought to arise mainly from the dysregulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the hyperactivation of the inflammatory response, highlighting the close interplay between dermatological and psychological health.

Sleep disturbances constitute another prevalent and clinically relevant concern in psoriasis. Patients commonly report poor sleep quality, which has been strongly associated with depression, anxiety, fatigue, and impaired daily functioning [12]. Elevated perceived stress and disrupted sleep patterns are, in turn, linked to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption [2,12]. These behaviors may exacerbate disease severity, diminish overall quality of life, and increase the risk of comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease [1317].

Psoriasis is widely recognized as a multifactorial disease, influenced by complex interactions between genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Among these, psychological stress plays a dual role, acting both as a trigger and a disease progressor, contributing to disease flares and exacerbations [18-20]. The impact of stress on psoriasis is thought to be mediated primarily through dysregulation of the HPA axis, a central system involved in stress regulation and immune modulation. Activation of the HPA axis leads to the sequential release of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone (CRH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, a glucocorticoid with potent anti-inflammatory properties.

Prior studies have demonstrated that patients with psoriasis often exhibit reduced cortisol levels, which may impair the physiological regulation of inflammatory responses and contribute to disease exacerbation [19,21]. Inadequate cortisol-mediated immunosuppression may predispose individuals to heightened inflammatory activity and increased disease severity. Concurrently, elevated levels of CRH have been observed in psoriatic patients, further supporting a direct link between psychological stress and inflammatory activation.

CRH plays a pivotal role in the transcriptional activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), a key regulator of inflammatory signalling pathways. NF- κB activation initiates a cascade of pro-inflammatory processes that are central to psoriasis pathogenesis. In the skin, CRH stimulates mast cell activation, leading to the release of pro- inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, IL-23) and tumor necrosis factor- alpha (TNF-α) [21-23]. These mediators promote neutrophil recruitment, increase vascular permeability, and amplify local inflammatory responses. The combination of elevated pro- inflammatory cytokine activity and diminished cortisol availability facilitates sustained inflammation and tissue damage in psoriatic lesions [18,19,24].

Given the central role of stress in both the psychological and immunological dimensions of psoriasis, stress management interventions have gained increasing attention as adjunctive therapeutic strategies. Mindfulness-based and cognitive– behavioral interventions have demonstrated beneficial effects on disease severity, psychological well-being, and physical functioning in patients with psoriasis [14,25,26]. Additionally, lifestyle modification programs targeting stress reduction and health-promoting behaviors have been shown to improve both psychological and physical outcomes in this population [27,28].

Given the multifactorial nature of psoriasis, we hypothesize that the implementation of a holistic stress management intervention may have beneficial effects for psoriatic patients.

The Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention (PSAI) represents a holistic stress management approach that integrates cognitive restructuring, self-reflection, and lifestyle modification [29]. Previous studies suggest that this technique may facilitate healthier behavioral patterns, enhance emotional regulation, and improve coping with daily stressors [30–34]. Its potential applicability to chronic stress-related conditions, such as psoriasis, warrants systematic investigation.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to explore the effects of PSAI on multiple stress- and disease-related outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Specifically, we assessed changes in perceived stress and stress-response indices (including HRV and hair cortisol levels), sleep quality, health-related behaviors, and emotional regulation. In addition, cognitive performance and body composition parameters [including body weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), Intermuscular Adipose Tissue (IMAT), Fat Mass (FM), and Fat-Free Mass (FFM)] were evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study was conducted at the Specialized Psoriasis Unit of “Andreas Syggros” Hospital for Skin and Venereal Diseases in Athens, Greece. “Andreas Syggros” Hospital is the largest tertiary referral centre for dermatological and venereal diseases in Greece and serves as a reference centre for the greater Athens area and southern Greece.

All participants were informed in detail about the objectives and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained prior to enrolment. The study protocol was approved by the Scientific and Ethics Committee of “Andreas Syggros” Hospital (Protocol No. 472/07-12- 2023) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants were recruited between January 2023 and March 2024. Inclusion criteria were: (a) a confirmed clinical diagnosis of psoriasis and (b) ability to communicate fluently in Greek. Exclusion criteria included: (a) current use of oral corticosteroids, (b) diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, and (c) substance abuse.

Study design

Given the limited sample size, a one-group pre-test–post-test design with a double pre-test was employed to enhance methodological rigor [35]. Participants underwent two baseline assessments before the intervention and one assessment following completion of the intervention. All assessments included both questionnaire-based measures and objective physiological measurements.

The present study adopted a quasi-experimental single-group pre–post intervention design without a separate control group. To enhance internal validity and strengthen causal inference, two baseline assessments were conducted prior to the intervention. This repeated -baseline approach enabled verification of temporal stability in participants’ performance before the intervention, thereby reducing the likelihood that post-intervention changes reflected spontaneous variation, maturation, or regression to the mean. The absence of systematic change across the two preintervention measurements suggests that participants’ performance trajectories remained stable in the absence of the intervention. In contrast, the emergence of systematic change only following the intervention indicates a temporal discontinuity consistent with an intervention-related effect. By using each participant as their own control, the within- subjects repeated-measures framework minimized inter-individual variability and increased sensitivity to detecting intervention-specific effects. Collectively, these design and analytic features support the interpretation that the observed post-intervention changes were primarily attributable to the implemented intervention.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted by comparing (a) the two preintervention measurements and (b) the second pre-intervention measurement with the post-intervention assessment. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range, were calculated for demographic variables and quantitative measures. For comparisons between the groups, Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed for normality testing. Wilcoxon tests or t-tests for two independent samples were used to compare the measurements prior to and after the intervention. Given the exploratory nature of this pilot study, no correction for multiple comparisons was applied. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Measures

Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ)

The Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ) is a self-report instrument assessing health-related lifestyle behaviors and perceived personal control. It includes items that focus on healthy eating habits, avoidance of harmful dietary choices, daily routines, engagement in organized physical exercise, and the promotion of social and mental well-being. While the questionnaire primarily evaluates lifestyle choices, some items also assess stress-related behaviours. The questionnaire consists of 26 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never/rarely to 4 = always), with higher total scores indicating stronger engagement in health- promoting behaviors and greater personal control over one’s lifestyle choices [36].

Health Locus of Control Scale (HLC)

The Health Locus of Control (HLC) Scale was used to assess participants’ beliefs regarding control over their health. The 18item scale comprises three subscales: internal control (HLC-1), external control (HLC-2), and chance control (HLC-3). HLC1 subscale measures the extent to which an individual believes they are responsible for their own health and well-being. HLC2 subscale assesses the degree to which individuals attribute their health to external factors, such as other people or societal influences. HLC-3 subscale reflects beliefs that health outcomes are governed by chance or random factors beyond the individual’s control. Higher scores reflect stronger endorsement of each control orientation as a determinant of health [37]. The Greek version of the scale has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties and has been widely used in previous studies [38,39].

Perceived Stress Scale-14 (PSS-14)

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) [40] is a self-report tool consisting of 14 items designed to assess the degree to which individuals perceive situations in their lives as stressful. The items measure the frequency of feelings and thoughts related to stress over the past month. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = very often). The scale includes seven positive and seven negative items. To calculate the total score, the ratings for the positive items are reversed, and the scores for all items are then summed. The total score can range from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 56, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress during the past month. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties when used within the Greek population [41].

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

Sleep quality was evaluated using the Greek version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The PSQI comprises 19 self-reported questions that are grouped into seven components, such as subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency (often referred to as usual sleep productivity), sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality. The overall PSQI score is calculated by summing the scores of all 7 components, with a possible total score ranging from 0 (indicating high sleep quality) to 21 (indicating poor sleep quality). A total score of ≥5 is indicative of poor sleep quality [42,43].

MedDiet Score

The MedDiet Score was developed to evaluate the degree of adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern. The overall score ranges from 0 to 56, with 0 indicating the lowest level of adherence and 56 representing the highest level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

Food consumption that closely aligns with Mediterranean dietary principles is rated higher, with scores ranging from 0 = never to 5 = highest consumption. Conversely, food consumption that deviates from the Mediterranean diet guidelines is assigned inverse scores, reflecting lower adherence [44].

State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS)

The State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS) is a 15-item self-report questionnaire assessing state levels of shame, guilt, and pride in response to specific situations. The scale also includes items related to pride. Participants rate their responses on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “I don’t feel that way at all” to “I feel very strongly that way” [45]. The scale has been validated in a Greek and has demonstrated good psychometric properties [46].

Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS)

Cognitive function was assessed using the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS), which includes the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised (BVMT-R), the California Verbal Learning Test–II (CVLT-II), and the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) [47]. These tests have been translated and validated for use in the Greek population [48].

Brief Visuospatial Memory Test Revised (BVMTR)

BVMTR is designed to assess visual memory through direct recall. During the task, the participant is first shown a series of abstract geometric shapes arranged in a 2x3 grid. The shapes are presented for a brief period, after which they are removed, and the participant is asked to reproduce the layout from memory, placing the correct shape in its original position. The participant is given three attempts, with a 10-second memorization period for each presentation. Each figure is scored based on two criteria: (a) whether the shape is correctly drawn, and (b) whether it is placed in the correct position. A maximum of 2 points can be awarded for each figure, yielding a maximum score of 12 points per attempt and a total possible score of 36 points across all three attempts California Verbal Learning Test-II (CVLT-II)

CVLT-II is a test that examines immediate word recall (verbal memory-immediate recall) with a duration of about 10 minutes. It includes a list of 16 words, falling into four conceptual groups, with four words each. The words are read aloud to the test taker five times with a gap of about one second between one word and the next. The test taker is then asked to recall as many words as possible from the list, in any order, and the process is repeated five times. The score is formed by the sum of the number of correct words in all attempts, with a maximum score of 80.

Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)

SDMT is a test that evaluates the speed of information processing. The test includes 9 different symbols corresponding to numbers from 1 to 9, and the participant is asked to mark under each number the symbol corresponding to 90 seconds. The total score is calculated from the sum of the correct answers.

State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI)

The State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) questionnaire examines how individuals respond or behave when they feel angry. The original inventory comprises 44 items [49], but in this study, the Greek version of the 24-item STAXI was used [50]. The items are rated on a four- point Likert-type scale (1 ¼ almost never to 4 ¼ almost always), three subscales: not expressing anger, expressing anger, and controlling anger. It has been standardized in Greek and has demonstrated good psychometric properties.

Biomedical indices

Body composition parameters, including body mass index (BMI), fat mass (FM), fat-free mass (FFM), and intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT), were assessed using the BIA-ACC device (BIOTEKNA© Biomedical Technologies, Venice, Italy), which has already been validated in the Greek population, against the absorption of dual-energy X-rays (DXA). This device analyzes body composition using a multilevel bioelectric frequency impedance. It is a non-invasive diagnostic tool that quickly and accurately detects a wide range of the patient’s body structure.

Heart rate variability (HRV) data were collected using the NeXus-10 system in combination with BioTrace+ software (Mind Media, Herten, The Netherlands). The NeXus system integrates HRV-BF with psychophysiological research and offers ECG data in both time and frequency domains using self-adhesive electrodes. The researcher manually initiated NeXus measurements at the start of the PPG data collection to ensure simultaneous acquisition of both PPG and ECG data [51].

Hair cortisol concentration

Hair samples were collected from the posterior vertex of the scalp at two pre-intervention time points and once following the intervention. Cortisol concentrations were analyzed retrospectively by segmenting hair samples. The most proximal 1 cm segment represented cortisol secretion over the preceding month, while the second proximal 1 cm segment reflected cortisol secretion during the month prior to that [52]. Hair cortisol concentration was used as an indicator of long- term HPA axis activity.

Analyses were conducted at the Unit of Clinical and Translational Research in Endocrinology, First Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and the Choremeio Research Laboratory in Athens, Greece.

Intervention

PSAI is based on the six core pillars of lifestyle medicine: healthy nutrition, regular physical activity, adequate and qualitative sleep, cultivation of healthy social relationships, stress management, and avoidance of harmful behaviors. The intervention protocol has been described in detail by Charalampopoulou et al. [30].

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Patients who declined participation, were unable to participate, or did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded from the study. Consequently, a total of 21 patients comprised the final study cohort (N = 21).

|

N (%) |

|

|

Gender |

|

|

Men |

10 (47.6) |

|

Women |

11 (52.4) |

|

Median Age (IQR) |

52 (16) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

Married |

12 (57.1) |

|

Single |

5 (23.8) |

|

Divorced |

3 (14.3) |

|

Widowed |

1 (4.8) |

|

Education |

|

|

High school |

4 (19) |

|

University |

9 (42.4) |

|

Technical Institute |

4 (19) |

|

Μaster’s degree |

4 (19) |

|

Employment status |

|

|

Employed |

17 (81) |

|

Unemployed |

2 (9.5) |

|

Retiree |

2 (9.5) |

|

Residency status |

|

|

Cohabitation |

18 (85.7) |

|

Alone |

3 (14.3) |

|

Home place |

|

|

Urban |

18 (85.7) |

|

Province |

3 (14.3) |

|

Parity |

|

Yes |

12 (57.1) |

|

No |

9 (42.9) |

|

Smoking |

|

|

Yes |

11 (52.4) |

|

No |

4 (19.0) |

|

Ex-smoker |

6 (28.6) |

|

Alcohol consumption |

|

|

Yes |

8 (38.1) |

|

No |

13 (61.9) |

|

Biological factors |

|

|

Skyrizi (Risankizumab) |

9 (42.9) |

|

Cosentyx (Secukinumab) |

4 (19.0) |

|

Bimzelx (Bimekizumab) |

3 (14.3) |

|

Tremfya (Guselkumab) |

3 (14.3) |

|

N presents numbers and relative (%) frequencies for qualitative variables and median and interquartile range for quantitative variables. |

|

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (Ν=21).

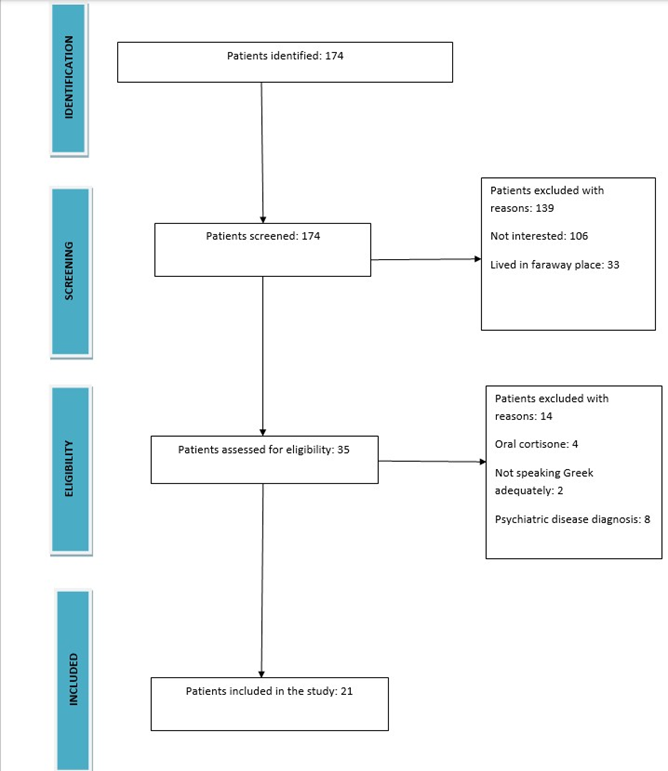

Of these participants, 10 were male (47.6%), and 11 were female (52.4%). All patients were receiving treatment with biologic agents at the time of the study; details are presented in the flow-diagram of the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow Diagram.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, the majority of participants were married (57.1%), university graduates (42.4%), employed (81.0%), cohabitating with a partner or family members (85.7%), and had children (57.1%). Lifestyle-related behaviors such as alcohol consumption and smoking were also assessed. More than half of the participants reported current smoking (52.4%), whereas the majority did not report alcohol consumption (61.9%).

Comparison Between the Two Pre-test Measurements

The comparison between the two pre-intervention assessments is presented in Table 2 and includes both questionnaire-based measures and biological markers. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two Pre-test measurements across the majority of variables, indicating relative stability of baseline measurements over time.

|

Scales and biomarkers |

1st measurement(t0) Median (IQR) Mean (SD)# |

2nd measurement(t1) Median (IQR) Mean # (SD) |

P-value |

|

HLPCQ |

# 59.38(15.79) |

# 59.71(15.67) |

0.723 |

|

HLC-I |

# 25.90(5.10) |

# 26.90(4.82) |

0.398 |

|

HLC-C |

24.00(4.50) |

24.00(9.50) |

0.101 |

|

HLC-E |

12.00(9.50) |

13.00(8.50) |

0.485 |

|

SSGS-CS |

6.00(7.00) |

6.00(5.50) |

0.191 |

|

SSGS-G |

10.00(11.50) |

9.00(11.00) |

0.213 |

|

SSGS-P |

21.00(6.50) |

22.00(5.50) |

0.343 |

|

PSS |

22.00(10.50) |

20.00(14.50) |

0.095 |

|

STAXI-A |

# 14.29(2.88) |

# 14.76(2.45) |

0.212 |

|

STAXI-B |

16.00(4.50) |

16.00(6.00) |

0.192 |

|

STAXI-C |

# 24.43(4.58) |

# 25.38(4.47) |

0.125 |

|

MD-S |

# 29.76(4.61) |

# 29.05(3.72) |

0.478 |

|

PSQI |

8.00(5.00) |

8.00(4.00) |

0.452 |

|

LF/HF |

1.50(1.80) |

2.00(1.15) |

0.779 |

|

HC |

# 8.73(3.43) |

# 9.93(5.10) |

0.100 |

|

FM% |

# 35.70(5.32) |

# 35.90(7.35) |

0.850 |

|

FFM% |

# 64.29(5.92) |

# 64.10(7.35) |

0.849 |

|

WEIGHT |

# 85.42(20.14) |

# 85.95(20.60) |

0.210 |

|

BMI |

# 29.43(6.28) |

# 29.59(6.35) |

0.274 |

|

IMAT |

# 2.03(0.69) |

# 2.04(0.69) |

0.780 |

|

SDMT |

52.00(10.50) |

59.00(11.50) |

0.004* |

|

CVLT-II |

70.00(11.50) |

74.00(14.00) |

0.386 |

|

BVMT-R |

30.00(5.50) |

30.00(9.50) |

0.379 |

|

BMI: Body Mass Index; BVMT-R: Brief Visuospatial Memory-Revised; CVLT-II: California Verbal Learning Test; FM: Fat Mass; FFM: Fat-Free Mass; HC: Hair Cortisol; HLC-C: Health Locus of Control -Chance; HLC-E: Health Locus of Control -External; HLC-I: Health Locus of Control –Internal; HLPCQ: Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire; IMAT: Intermuscular Adipose Tissue; ; LF/HF: Low Frequency/High Frequency; MD-S: MedDiet- Score; PSAI: Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SSGS-CS: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Current Shame; SSGS-G: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Guilt; SSGS-P: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Pride; ; STAXI: State Trait Anger Expression Inventory; W: Weight; #: Mean( SD) |

|||

Table 2: Comparison of the two pretest measurements (t0-t1).

An exception was observed for the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), which showed a statistically significant difference between the two Pre-test measurements (p = 0.004). This finding indicates variability in processing speed performance across baseline assessments and was considered in subsequent analyses.

Comparison Between Pre-test and Post-test Measurements

To evaluate the effects of the intervention, the second Pre-test measurement was used as the baseline comparator for post-intervention outcomes. The results of these comparisons are summarized in Table 3.

|

Scales and Biomarkers |

Prior PSAI(t1) Median (IQR) # Mean (SD) |

After PSAI(t2) Median # (IQR) Mean (SD) |

Effect Size r Cohen’s d# |

P-value |

|

HLPCQ |

# 59.71(15.67) |

# 66.90(12.65) |

# -0.99 |

<0.01* |

|

HLC-I |

# 26.90(4.82) |

# 29.00(5.08) |

# -0.72 |

0.003* |

|

HLC-C |

24.00(9.50) |

19.00(10.50) |

-0.23 |

0.285 |

|

HLC-E |

13.00(8.50) |

10.00(6.00) |

-0.17 |

0.432 |

|

SSGS-CS |

6.00(5.50) |

5.00(3.50) |

-0.41 |

0.151 |

|

SSGS-G |

9.00(11.00) |

8.00(6.00) |

-0.49 |

0.025* |

|

SSGS-P |

22.00(6.50) |

23.00(5.50) |

-0.19 |

0.374 |

|

PSS |

20.00(14.50) |

18.00(9.00) |

-0.49 |

0.025* |

|

STAXI-A |

# 14.76(2.45) |

# 13.76(2.34) |

# 0.48 |

0.041* |

|

STAXI-B |

16.00(6.00) |

13.00(16.00) |

-0.30 |

0.163 |

|

STAXI-C |

# 25.38(4.47) |

# 26.81(4.20) |

# -0.49 |

0.036* |

|

MD-S |

# 29.05(3.72) |

# 30.76(3.91) |

# -0.49 |

0.037* |

|

PSQI |

8.00(4.00) |

6.00(2.50) |

-0.58 |

0.008* |

|

LF/HF |

2.00(1.15) |

1.20(0.65) |

-0.72 |

<0.01* |

|

HC |

# 9.93(5.10) |

# 15.47(10.43) |

# 0.43 |

0.017* |

|

FM% |

# 35.90(7.35) |

# 32.81(9.10) |

# 0.76 |

0.002* |

|

FFM% |

# 64.10(7.35) |

# 67.30(8.98) |

# -0.79 |

0.002* |

|

WEIGHT |

# 85.90(20.60) |

# 84.76(19.46) |

# 0.38 |

0.098 |

|

BMI |

# 29.60(6.35) |

# 29.19(6.01) |

# 0.37 |

0.108 |

|

IMAT |

# 2.04(0.69) |

# 1.87(0.75) |

0.86 |

<0.01* |

|

SDMT |

59.00(11.50) |

55.00(8.00) |

-0.52 |

0.017* |

|

CVLT-II |

74.00(14.00) |

75.00(7.00) |

-0.58 |

0.008* |

|

BVMT-R |

30.00(9.50) |

34.00(6.00) |

-0.66 |

0.002* |

|

BMI: Body Mass Index; BVMT-R: Brief Visuospatial Memory-Revised; CVLT-II: California Verbal Learning Test; FM: Fat Mass; FFM: Fat- Free Mass; HC: Hair Cortisol; HLC-C: Health Locus of Control -Chance; HLC-E: Health Locus of Control -External; HLC-I: Health Locus of Control –Internal; HLPCQ: Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire; IMAT: Intermuscular Adipose Tissue; LF/HF: Low Frequency/High Frequency; MD-S: MedDiet- Score; PSAI: Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SSGS-CS: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Current Shame; SSGS-G: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Guilt; SSGS-P: State Shame and Guilt Scale-Pride; STAXI: State Trait Anger Expression Inventory; W: Weight. |

||||

Table 3: Comparison of the pretest with post-test measurements (t1-t2).

Overall, statistically significant changes were observed across the majority of assessed domains following the intervention. No significant changes were detected in selected subscales of the HLC, the SSGS, the STAXI, or in the biomedical indices of body weight and BMI.

Significant improvements were primarily observed in healthrelated and stress-related parameters. Specifically, scores on the HLPCQ increased significantly, demonstrating a large effect size (p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.99). In addition, the internal locus of control subscale of the HLC (HLC-I) showed a statistically significant increase with a large effect size (p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = −0.72).

Regarding stress-related indices, perceived stress levels decreased significantly following the intervention, as measured by the PSS14, with a moderate effect size (p = 0.025, r = −0.49). Autonomic regulation, as indexed by HRV, demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the LF/HF ratio, corresponding to a large effect size (p = 0.01, r = −0.72). Furthermore, hair cortisol concentrations increased significantly following the intervention, with a moderate-to- large effect size (p = 0.017, r = 0.43).

Significant changes were also observed in body composition parameters. Fat mass (FM), fat-free mass (FFM), and intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) demonstrated statistically significant changes, all associated with large effect sizes (FM: p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.76; FFM: p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = −0.79; IMAT: p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.86).

Cognitive performance outcomes assessed with the BICAMS battery showed mixed results. Statistically significant improvements were observed in verbal learning and visuospatial memory, as indicated by increases in median scores on the CVLTII (p = 0.008, r = −0.58) and BVMT-R (p = 0.002, r = −0.66), both reflecting moderate effect sizes. In contrast, performance on the SDMT showed a statistically significant decrease following the intervention (p = 0.017, r= −0.52), despite improvements observed in other cognitive domains.

Discussion

The present study explored the effects of a holistic stress management intervention based on the Pythagorean Self-Awareness Technique on psychological, physiological, cognitive, and lifestyle-related outcomes in patients with psoriasis undergoing biological therapy targeting interleukins. The primary aim was to reduce stress-related burden, given the established role of psychological stress as both a triggering and aggravating factor in psoriasis [18-20]. Overall, the findings suggest that participation in the intervention was associated with improvements across multiple domains relevant to stress regulation and disease-related well- being, although results should be interpreted within the context of the exploratory study design.

A significant reduction in perceived stress levels was observed following the intervention, accompanied by favourable changes in autonomic nervous system activity as assessed by HRV. HRV represents an objective biomarker of stress response, reflecting the dynamic balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity. Increased sympathetic activation is typically observed under stressful conditions, whereas parasympathetic predominance is associated with relaxation and adaptive stress regulation. In the present study, the postintervention reduction in the LF/HF ratio suggests a shift toward improved autonomic balance and enhanced parasympathetic modulation. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that stress management interventions, including mindfulness-based and cognitive–behavioral approaches, are associated with improved HRV indices and reduced perceived stress [25,26,53-56]. Moreover, reduced HRV has been linked to unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep disturbances, and substance use [53,54], further supporting the relevance of the observed autonomic changes in the context of broader lifestyle modification. Previous studies have also indicated that PSAI can positively influence HRV [57].

In parallel with improvements in subjective and autonomic stress markers, the intervention was associated with increased hair cortisol concentrations. Patients with psoriasis and other autoinflammatory or allergic conditions have been reported to exhibit lower cortisol levels, reflecting dysregulation of the HPA axis and insufficient glucocorticoid -mediated suppression of inflammatory processes [21-23,58]. The observed increase in hair cortisol concentrations may indicate a partial normalization of long-term cortisol secretion patterns following stress reduction. To our knowledge, this is the first interventional study assessing hair cortisol as a biomarker of chronic stress in psoriasis patients undergoing a holistic stress management program. Nevertheless, given the absence of a control group, these findings should be interpreted as preliminary and hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive evidence of HPA axis restoration.

Sleep quality also improved significantly following the intervention, as indicated by PSQI measurements. Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent among psoriatic patients and are commonly attributed to pruritus, pain, psychological distress, and heightened stress levels [16,59-61]. Improvements in sleep quality observed in the present study may reflect reduced stress perception and improved emotional regulation. Enhanced sleep quality may, in turn, contribute to improvements in mood, cognitive performance, and daily functioning, highlighting the bidirectional relationship between sleep and psychological wellbeing in chronic inflammatory conditions.

Regarding emotional regulation, reductions in negative emotional states such as anger, shame, and guilt were observed, although not all subscales demonstrated statistically significant changes. Psoriasis is frequently associated with stigma, body image disturbances, and social withdrawal, leading to heightened emotional distress and reduced self-esteem [21,62]. Psoriatic patients have low self-esteem and, as a result, they may avoid social interactions and experience challenges in occupational, sexual, and general daily functioning [27,63]. The observed reductions in guilt and improvements in anger expression and control may reflect increased self-awareness and adaptive coping strategies fostered by the intervention. The lack of statistically significant changes in some emotional subdomains may be attributable to the relatively short duration of the intervention, although trends toward improvement were evident.

The literature has shown that PSAI enhances the cognitive skills of individuals [30,64,65]. Cognitive performance outcomes demonstrated selective improvements. Specifically, verbal learning and visuospatial memory showed significant enhancement following the intervention, whereas information processing speed, as measured by the SDMT, did not improve and showed variability across assessments. Chronic stress has been shown to negatively affect cognitive function, particularly processes mediated by the prefrontal cortex, including memory and executive functioning. Reduced stress levels, improved sleep quality, and healthier lifestyle behaviors may collectively contribute to the observed cognitive benefits. The mixed findings across cognitive domains underscore the complexity of cognitive functioning in psoriasis and warrant further investigation in larger, controlled studies.

Improvements in health-related behaviors and perceived control over health were also observed. Participants demonstrated increased internal health locus of control and significant enhancement in healthy lifestyle behaviors, as reflected by HLPCQ and MedDiet scores. These findings suggest that the intervention may have facilitated greater personal responsibility for health- related decisions, aligning with the theoretical framework of Pythagorean Self-Awareness, which emphasizes self-reflection, discipline, and conscious behavioral choices. Changes in body composition, including reductions in fat mass and intermuscular adipose tissue, further support the potential impact of lifestyle modification, although changes in body weight and BMI did not reach statistical significance, likely due to the short duration of the intervention.

Collectively, these findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating the beneficial effects of the PSAI in populations with chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, depressive disorders, multiple sclerosis, breast cancer, and irritable bowel syndrome [30-34,66,67]. In general, the techniques that have been performed in people with psoriasis are Mindfulness and the visualization technique, which have shown significant results. These are techniques that focus on stress management only and not on a holistic, healthy lifestyle approach in general. However, these techniques primarily focus on stress management and may not impact both physical and mental health as comprehensively as PSAI appears to do in this preliminary study.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The small sample size and lack of a control group limit the generalizability of the findings and preclude causal inferences. Additionally, the absence of comparison with another established stress management intervention restricts conclusions regarding the relative efficacy of the PSAI. Future randomized controlled trials with larger samples, longer follow-up periods, and comparative intervention arms are needed to confirm and extend the present findings. Future research should also explore the long-term sustainability of these effects and their applicability in diverse patient populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this exploratory study suggest that a holistic stress management intervention based on the Pythagorean Self-Awareness Technique appeared to be associated with improvements in stress regulation, sleep quality, emotional wellbeing, cognitive performance, health-related behaviors, and specific physiological biomarkers in patients with psoriasis receiving biologic therapy. While these results are preliminary, they support the feasibility and potential value of integrating holistic, lifestyleoriented stress management strategies as adjunctive approaches in psoriasis care. Future controlled studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and determine the clinical relevance of these effects.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all patients for participating in the study. Their contribution was essential to the successful completion of this study. Also, we are grateful to Clinical Chemist Mantzou Α. for her assistance with hair cortisol analysis. The authors would like to thank Tamiolaki E. and Giannakopoulou M. for their valuable assistance with data collection and participant assessments.

Clinical Trials Registry Site and Number

Clinicaltrial.gov, NCT06691763. The study protocol was approved by the hospital’s Scientific and Ethics Committee (Protocol number:472/07-12-2023) and was consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Schäfer T (2006) Epidemiology of psoriasis: review and the German perspective. Dermatology 212: 327-337.

- Christophers E (2001) Psoriasis- epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin Exp Dermatol 26: 314-320.

- Langley RGB, Krueger GG, Griffiths C (2005) Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis 64: ii18-ii23.

- Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT (2007) Psoriasis: epidemiology. Clin Dermatol 25: 535-546.

- Zieciak T, Rzepa T, Król J, Zaba R (2017) Stigmatization feelings and depressions symptoms in psoriasis patients. Psychiatr Pol 51: 11531163.

- Innamorati M, Quinto RM, Lester D, Iani L, Graceffa D, et al. (2018) Cognitive impairment in patients with psoriasis: a matched casecontrol study. J Psychosom Res 105: 99-105.

- Colgecen E, Celikbilek A, Keskin DT (2016) Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Psoriasis: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Am J Clin Dermatol 17: 413-419.

- Padma K, Nanaware S, Yadiyal A, Mathai PJ (2020) Cognitive impairment in patients with psoriasis: A clinical study in teaching hospital. J Fam Med Prim Care 9: 4001-4004.

- Yen H, Yen H, Chi CC (2021) Is psoriasis associated with dementia or cognitive impairment? A Critically Appraised Topic. Br J Dermatol 184: 34-42.

- Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R (2011) Stress and quality of life in psoriasis: an update. Int J Dermatol 50: 783-792.

- Amin M, Lee E, Tsai T, Wu J (2020) Psoriasis and Co-morbidity. Acta Derm Venereol 100: 81-87.

- Yuksel EP, Durmus D, Sarisoy G (2019) Perceived stress, life events, fatigue and temperament in patients with psoriasis. J Int Med Res 47: 4284-4291.

- Roszkiewicz M, Dopytalska K, Szymanska E, Jakimiuk A, Walecka I (2020) Environmental risk factors and epigenetic alternations in psoriasis. Ann Agric Environ Med 27: 335-342.

- Kaaz K, Szepietowski J, Matusiak L (2019) Influence of Itch and Pain on Sleep Quality in Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 99: 175-180.

- Krajewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W (2018) Sleep disorders in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Reumatologia 56: 301-306.

- Tas B, Kabeloglu V, Soysal A, Atakli D (2020) Sleep quality in psoriasis patients and its relations with possible affecting factors. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul 54: 181-187.

- Salihbegovic E, Kurtalic N, Omerk E (2021) Smoking Cigarettes and Consuming Alcohol in Patients with Psoriasis. Mater Sociomed 33: 30.

- Hunter HJA, Griffiths CEM, Kleyn CE (2013) Does psychosocial stress play a role in the exacerbation of psoriasis? Br J Dermatol 169: 965974.

- Gisondi P, Geat D, Bellinato F, Spiazzi L, Danese E, et al. (2021) Psychological Stress and Salivary Cortisol Levels in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis. J Pers Med 11: 1069.

- Bulat V, Šitum M, Delaš Aždajic M, Lovric I, Dediol I (2020) Study on the Impact of Psoriasis on Quality of Life: Psychological, Social and Financial Implications. Psychiatr Danub 32: 553-561.

- Brunoni AR, Santos IS, Sabbag C, Lotufo PA, Benseñor IM (2014) Psoriasis severity and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function: results from the CALIPSO study. Braz J Med Biol Res 47: 1102-1106.

- Marek-Jozefowicz L, Czajkowski R, Borkowska A, Nedoszytko B, Zmijewski MA, et al. (2022) The Brain–Skin Axis in Psoriasis— Psychological, Psychiatric, Hormonal, and Dermatological Aspects. Int J Mol Sci 23: 669.

- Rousset L, Halioua B (2018) Stress and psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 57: 1165-1172.

- Wozniak E, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W (2021) Psychological Stress, Mast Cells, and Psoriasis—Is There Any Relationship? Int J Mol Sci 22: 13252.

- Timis TL, Florian IA, Mitrea DR, Orasan R (2021) Mind -body interventions as alternative and complementary therapies for psoriasis: a systematic review of the English literature. Medicina 57: 410.

- Maddock A, Hevey D, D’Alton P, Kirby B (2019) A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with psoriasis patients. Mindfulness 10: 2606-2619.

- Van Acht MR, Van den Reek JM, De Jong EM, Seyger MM (2022) The effect of lifestyle changes on disease severity and quality of life in patients with plaque psoriasis: A narrative review. Psoriasis 12: 35-51.

- Yeroushalmi S, Hakimi M, Chung M, Bartholomew E, Bhutani T, et al. (2022) Psoriasis and exercise: a review. Psoriasis 12: 189-197.

- Burke J, Dunne PJ (2022) Lifestyle medicine pillars as predictors of psychological flourishing. Front Psychol 13: 963806.

- Charalampopoulou M, Bacopoulou F, Syrigos KN, Filopoulos E, Chrousos GP, et al. (2020) The effects of Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention on breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant therapy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Breast 49: 210-218.

- Athanasopoulou S, Simos D, Charalampopoulou M, Tentolouris N, Kokkinos A, et al. (2021) Significant improvement of stress and aging biomarkers using a novel stress management program with the cognitive restructuring method “Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention” in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and healthy adults. Mech Ageing Dev 198: 111538.

- Gorgili K, Artemiadis A, Bacopoulou F, Karatzas P, Tigani X, et al. (2021) The Effects of Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention on Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients: A Non-randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Exp Med Biol 1337: 345-354.

- Psarraki EE, Bacopoulou F, Panagoulias E, Michou M, Pelekasis P, et al. (2021) The effects of Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention on patients with major depressive disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res 138: 326-334.

- Panagopoulou Z, Artemiadis A, Chrousos GP, Darviri C, Anagnostouli MC (2022) Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention for Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Quasi- Experimental Pragmatic Trial. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 37: 125-132.

- Knapp TR (2016) Why is the one-group pretest–posttest design still used? Clin Nurs Res 25: 467-472.

- Darviri C, Alexopoulos EC, Artemiadis AK, Tigani X, Kraniotou C, et al. (2014) The Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ): a novel tool for assessing self-empowerment through a constellation of daily activities. BMC Public Health 14: 995.

- Wallston BS, Wallston KA, Kaplan GD, Maides SA (1976) Development and validation of the Health Locus of Control (HLC) Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 44: 580-585.

- Christaki E, Kokkinos A, Costarelli V, Alexopoulos EC, Chrousos GP, et al. (2013) Stress management can facilitate weight loss in G reek overweight and obese women: a pilot study. J Hum Nutr Diet 26: 132139.

- Tigani X, Artemiadis AK, Alexopoulos EC, Chrousos GP, Darviri C (2011) Gender differences in Greek centenarians. A cross-sectional nation-wide study, examining multiple socio-demographic and personality factors and health locus of control. BMC Geriatr 11: 1-8.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24: 385-396.

- Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, et al. (2011) Perceived stress scale: Reliability and validity study in Greece. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8: 3287-3298.

- Fabbri M, Beracci A, Martoni M, Meneo D, Tonetti L, et al. (2021) Measuring subjective sleep quality: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18: 1082.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28: 193-213.

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C (2007) Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med 44: 335340.

- Cavalera C, Pepe A, Zurloni V, Diana B, Realdon O (2017) A short version of the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS-8). TPM 24: 99106.

- Tzelepi I, Sotiropoulou L, Bacopoulou F, Charalampopoulou M, Zigkiri E, et al. (2023) Validation of the Greek Version of the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS). Adv Exp Med Biol 1425: 79-91.

- Benedict RH, Amato MP, Boringa J, Brochet B, Foley F, et al. (2012) Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS): international standards for validation. BMC Neurol 12: 55.

- Polychroniadou E, Bakirtzis C, Langdon D, Lagoudaki R, Kesidou E, et al. (2016) Validation of the Brief International Cognitive Assessment for Multiple Sclerosis (BICAMS) in Greek population with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 9: 68-72.

- Spielberger CD (1985) Emotional reactions to stress: Anxiety and Anger. How to define and research stress 65-70.

- Anagnostopoulou T, Kioseoglou G (2012) State–trait anger expression inventory. In: Stalikas A, Triliva S and Roussi P(eds). The Psychometric Instruments in Greece: A Comprehensive Collection and Presentation of Questionnaires, Tests, Instruments and Assessments Kits in Greece. Athens: Topos, p. 576.

- van Dijk W, Huizink AC, Oosterman M, Lemmers-Jansen ILJ, de Vente W (2023) Validation of Photoplethysmography Using a Mobile Phone Application for the Assessment of Heart Rate Variability in the Context of Heart Rate Variability-Biofeedback. Psychosom Med 85: 568-576.

- Wester VL, van Rossum EF (2015) Clinical applications of cortisol measurements in hair. Eur J Endocrinol 173: M1-M10.

- Strüven A, Holzapfel C, Stremmel C, Brunner S (2021) Obesity, nutrition and heart rate variability. Int J Mol Sci 22: 4215.

- Kim HG, Cheon EJ, Bai DS, Lee YH, Koo BH (2018). Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig 15: 235.

- Meina M, Ratajczak E, Sadowska M, Rykaczewski K, Dreszer J, et al. (2020) Heart rate variability and accelerometry as classification tools for monitoring perceived stress levels—a pilot study on firefighters. Sensors 20: 2834.

- Seipäjärvi SM, Tuomola A, Juurakko J, Rottensteiner M, Rissanen APE, et al. (2022) Measuring psychosocial stress with heart rate variability- based methods in different health and age groups. Physiol Meas 43: 055002.

- Angelopoulou K, Zaverdinou E, Bacopoulou F, Chrousos GP, Giannakakis G, et al. (2022) The effect of pythagorean self-awareness on heart rate variability, perceived stress and behavior of preschool children. Children (Basel) 9: 1529.

- Priftis KN, Papadimitriou A, Nicolaidou P, Chrousos GP (2008) The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in asthmatic children. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19: 32-38.

- Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak L (2019) Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 99: 175-180.

- Krajewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W (2018) Sleep disorders in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Reumatologia 56: 301.

- Melikoglu M (2017) Sleep quality and its association with disease severity in psoriasis. Eurasian J Med 49: 124-127.

- Rendon A, Schäkel K (2019) Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci 20: 1475.

- Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R (2011) Stress and quality of life in psoriasis: an update. Int J Dermatol 50: 783-792.

- Darviri C, Zavitsanou C, Delikou A, Giotaki A, Artemiadis A, et al. (2016) Pythagorean self-awareness serves successfully as a new cognitive behavioral-based technique in multiple sclerosis physical and psychosocial well- being and quality of life. Psychology 7: 572.

- Zigkiri ES, Nicolaides NC, Bacopoulou F, Simos D, Vlachakis D, et al. (2020) The effect of the pythagorean self-awareness intervention on psychological, lifestyle and cognitive measures of a community sample. J Mol Biochem 9: 32.

- Pipelias P, Bacopoulou F, Chrousos G, Tentolouris N, Bonakis A, et al. (2025) Impact of a novel, non-pharmaceutical, cognitive- behavioral stress management technique “Pythagorean selfawareness intervention” on the stress levels of adult patients with non-communicable diseases: A systematic review. Research Square.

- Georgopoulou A, Laskaridou GE, Charalampopoulou M, Anastasiou IA, Mantikas V, et al. (2025) Significant Improvement of Oxidative Stress and the Fear of Recurrence in Women with Breast Cancer, Using a Novel Stress Management Program with the Cognitive Restructuring Method “Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention”. J Oncol Res Ther 10: 10320.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.