Significant Improvement of Oxidative Stress and the Fear of Recurrence in Women with Breast Cancer, Using a Novel Stress Management Program with the Cognitive Restructuring Method

by Alexia Georgopoulou1, Georgia E. Laskaridou1, Maria Charalampopoulou1,2*, Ioanna A. Anastasiou3, Vasileios Mantikas4, Panagiotis Sideris5, Michalis Mykoniatis1, Aimilia Mantzou6, Annezo

Marinatou7, Panagiotis Daskalakis7, George P. Chrousos8, Christina Darviri1

1Postgraduate Course of Stress Management and Health Promotion, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

2Breast Unit, First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

3First Department of Propaedeutic Internal Medicine, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laiko General Hospital, Athens, Greece

4Department of Geriatrics, Gesundheitszentrum Dielsdorf, Dielsdorf, Switzerland.

5Internal Medicine Department,417 Share Fund Hospital, Athens, Greece

6Laboratory of the Clinical and Translational Research Unit in Endocrinology, Athens, Greece

7Breast Unit, Elena Venizelou General Hospital, Athens, Greece

8First Department of Paediatrics, Aghia Sophia Children’s Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

*Corresponding author: Maria Charalampopoulou, Breast Unit, First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Hippokratio Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Athens, Greece.

Received Date: 14 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 27 December, 2025

Published Date: 31 December, 2025

Citation: Georgopoulou A, Laskaridou GE, Charalampopoulou M, Anastasiou IA, Mantikas V, et al. (2025) Significant Improvement of Oxidative Stress and the Fear of Recurrence in Women with Breast Cancer, Using a Novel Stress Management Program with the Cognitive Restructuring Method “Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention”. J Oncol Res Ther 10:10320. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10320

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer survivors frequently experience psychological distress, including fear of cancer recurrence, which may be influenced by oxidative stress and lifestyle factors. Although holistic stress-management interventions show promise, evidence remains limited. Aim: To evaluate whether a six-week stress-management intervention improves fear of recurrence, oxidative stress status, and lifestyle, psychological, and biological parameters in breast cancer survivors. Methods: In this non-blinded randomized study, 70 women were allocated to either an intervention group receiving the Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention (PSAI) or a control group receiving brief lifestyle advice and diaphragmatic breathing instruction. Assessments at baseline and post-intervention included lifestyle behaviors, sleep quality, perceived stress, depression, anxiety, stress, self-efficacy, fear of recurrence, oxidative stress, antioxidant capacity, hair cortisol, and BMI. Results: Sixty-eight participants completed the study (intervention n = 35; control n = 33). Compared with controls, the intervention group showed greater improvements in oxidative stress (p = 0.018), antioxidant capacity (p < 0.001), and recurrence worries (p = 0.034). Significant between-group differences were also observed in lifestyle behaviors, sleep quality, perceived stress, depression, stress, self-efficacy, and BMI (all p < 0.05). Anxiety and hair cortisol did not change significantly. No adverse events were reported. Conclusions: The PSAI appears to be a safe and effective brief stress-management intervention that may improve psychological functioning, lifestyle behaviors, and redox balance in breast cancer survivors. Larger long-term studies are warranted.

Keywords: Breast Cancer Survivors; Stress Management; Oxidative Stress; Fear of Recurrence; Lifestyle Medicine; Randomized Controlled Trial;

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and survival rates continue to improve due to early detection and advances in treatment [1]. Despite treatment success, many survivors experience persistent physical and psychosocial difficulties that impair quality of life. Fear recurrence of cancer is particularly common, regardless of prognosis [2, 3] and is defined as the fear or worry that cancer will return or progress in the same or another part of the body [4]. This fear ranges from an adaptive response to a clinically significant condition and, when severe, is associated with psychological dysfunction, including anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and somatic complaints [5-7]. High levels of the fear of recurrence is associated with increased perceived stress and elevated hair cortisol, a biomarker of chronic stress [7-10]. Conversely, high life stress may predict greater fear of recurrence [11]. Psychological stress also contributes to increased production of reactive oxygen species [12], and perceived stress and cortisol have been positively associated with oxidative status [13].

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses, leading to cellular damage [14]. Chronic oxidative stress promotes cellular injury and contributes to breast carcinogenesis through mechanisms such as telomere shortening and DNA damage [15, 16]. Breast cancer cells also exhibit higher ROS levels than normal cells [17, 18].

Recent stress-management interventions, including MindfulnessBased Stress Reduction, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and relaxation techniques, have shown beneficial psychological and physical effects in breast cancer populations, although evidence remains limited [19, 20]. Only a few holistic programs integrating lifestyle medicine have been implemented, with encouraging results [21-23]. While mindfulness-based and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy interventions reduce fear of recurrence, no psychological intervention has yet specifically targeted oxidative stress [24].

The holistic program examined in this study is the Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention (PSAI), a structured cognitive– contemplative approach previously shown to improve psychological well-being and health-related behaviors [22], but not previously examined in relation to fear of cancer recurrence or oxidative stress. Based on the links between stress, oxidative status, and fear of recurrence, we examined whether the PSAI could simultaneously improve psychological and biological outcomes during survivorship.

Accordingly, this intervention study aimed to evaluate the effects of a holistic stress-management program on fear of cancer recurrence and oxidative stress (primary outcomes), as well as on lifestyle behaviors, perceived stress, depression, anxiety, sleep quality, selfefficacy, hair cortisol, and body mass index (secondary outcomes) in breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This non-blinded, randomized clinical study was conducted at the Interdepartmental Breast Unit of the General Hospital Elena Venizelou in Athens, Greece, between February and May 2025. Ethical approval was obtained from the institution’s Scientific and Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 1640/23-1-25), and all procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were recruited after receiving oral and written explanations regarding the study aims and procedures, and enrollment required signed informed consent.

Eligible women were required to have a histologically confirmed diagnosis of primary invasive breast cancer Stage I–III, to have completed all adjuvant treatments at least three months prior to participation (with the exception of ongoing hormonal therapy), to be aged 18 years or older at study entry, and to have been diagnosed within the previous five years. Exclusion criteria consisted of current psychiatric medication use, presence or history of metastatic disease, previous participation in stress-management or lifestyle-modification interventions, and inadequate Greeklanguage comprehension that would impede questionnaire completion and program engagement.

Participant Allocation

Potentially eligible individuals were identified through hospital medical records and contacted either during clinical visits or by telephone. After informed consent was obtained, participants were randomized to the intervention or control group using a computergenerated sequence (www.random.org). Due to the nature of behavioral intervention, blinding was not feasible for either researchers or participants.

Measurements

Sociodemographic, Health and Disease-Related Characteristics

Baseline information on age, parental status, educational attainment, employment status and perceived financial sufficiency was collected through self-report. Smoking and alcohol consumption, menopausal status, years since diagnosis, tumor stage, type of surgery, and history of adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormonal therapy were obtained through participant report and verified via medical records.

Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ)

Lifestyle behavior was assessed using the 26-item HLPCQ [25], scored on a four-point frequency scale from “never or rarely” to “always.” The instrument evaluates dietary choices, dietary harmavoidance behaviors, daily routine stability, structured physical exercise and social/mental balance. Higher scores reflect greater lifestyle-related self-empowerment. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.82 at baseline and 0.89 at post-intervention.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

Sleep quality was measured with the Greek-validated PSQI [26, 27]. The index includes 19 items addressing sleep duration, latency, efficiency, nocturnal disturbances, sleep medication use and daytime functioning. Higher global scores indicate poorer sleep. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83 at baseline and 0.77 following intervention.

Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS)

Fear of cancer recurrence was assessed using the Greek version of the CARS [28]. Four items quantify global recurrence fear on a sixpoint scale, and 26 items assess domain-specific worries relating to health, role functioning, womanhood and death on a five-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater concern. Internal consistency in this sample was 0.96 at baseline and 0.97 post-intervention.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)

Stress perception during the preceding month was evaluated using the 14-item PSS [29], validated for Greek populations by [30]. Seven positively worded items were reverse-scored and summed with negative items to yield a total score, where higher values represent greater perceived stress. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 at baseline and 0.87 post-intervention.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21)

Depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms were measured with the DASS-21 [31, 32]. Respondents rated experiences over the preceding week on a four-point severity scale. Higher subscale scores reflect greater symptom severity. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.80 to 0.87 across dimensions and timepoints.

General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)

Self-efficacy was measured using the Greek-validated GSES [33, 34]. The scale consists of ten items rated from 1 (“not at all true”) to 4 (“exactly true”). Higher scores denote stronger perceived selfefficacy. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 at baseline and 0.91 at study completion.

Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Capacity

Venous blood was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes, and serum aliquots were stored at −80°C. All samples were analyzed in duplicate. Oxidative stress was quantified using a commercial TOS ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) calibrated with internal standard curves. Antioxidant capacity was assessed via DPPH radical-scavenging activity following deproteinization with Proteinase K, methanolic dilution and spectrophotometric detection at 517 nm, standardized against Trolox equivalents.

Hair Cortisol

Hair was sampled from the posterior vertex, with the proximal 3 cm reflecting approximately three months of integrated cortisol secretion. Samples (20–40 mg) were homogenized at 5,000 rpm, extracted for 16 hours in methanol, dried at room temperature, reconstituted in PBS and analyzed using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Cobas e411). The assay detection limit was 0.054 µg/dL.

Intervention Group

The intervention group participated in a structured Pythagorean Self-Awareness Intervention (PSAI) program designed to enhance stress management and self-regulation through systematic cognitive and introspective training. The PSAI is a mental stressmanagement technique designed to cultivate self-awareness, cognitive reconstruction, and self-improvement, grounded in the moral framework of the Golden Verses of the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras. The intervention was structured as a contemplative–cognitive training method aiming to enhance selfregulation through systematic self-observation, memory recall, and ethical self-appraisal. By engaging participants in a twicedaily structured introspective exercise, PSAI promotes conscious awareness of behaviors, emotions, and cognitive patterns related to health and daily functioning. The repeated activation of autobiographical memory and evaluative self-processing is hypothesized to strengthen metacognitive control mechanisms and facilitate adaptive behavioral regulation. The neurophysiological substrate of the technique is the activation of the Default Mode Network, which supports self-referential processing, memory retrieval, and introspective cognition. Through cognitively guided self-evaluation, participants are encouraged to detect maladaptive choices and unhealthy behaviors and to initiate self-correction toward improved quality of life. Through its morally guided reflective process, PSAI supports intentional lifestyle modification, emotional self-regulation, and stress reduction, thereby fostering psychophysiological resilience. The intervention integrates ancient ethical principles with contemporary neurocognitive models of self-referential processing, offering a theoretically grounded approach to sustained behavioral change and psychological wellbeing. For a detailed description of the theoretical framework and practical implementation of PSAI, see Charalampopoulou et al., 2020.

Control Group

Control participants completed baseline and follow-up assessments one month apart. They attended an individual instructional session introducing diaphragmatic breathing and received brief lifestyle guidance. They were asked to perform breathing exercises twice daily but received no further coaching or structured behavioral support.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline comparisons were performed with Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables, and with Student’s t-tests or Mann– Whitney U tests for continuous data. Normality of distributions was assessed prior to test selection using the Shapiro–Wilk criterion and inspection of Q–Q plots. Between-group effects were determined by comparing change scores (post-intervention minus baseline). Effect sizes were calculated through SPSS for parametric tests and as rho=(Z/√N) for non-parametric analyses, interpreted as small (<0.30), moderate (0.30–0.50) or large (>0.50). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. BMI was calculated as kg/m². All analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0.

Results

Study Participants’ Characteristics

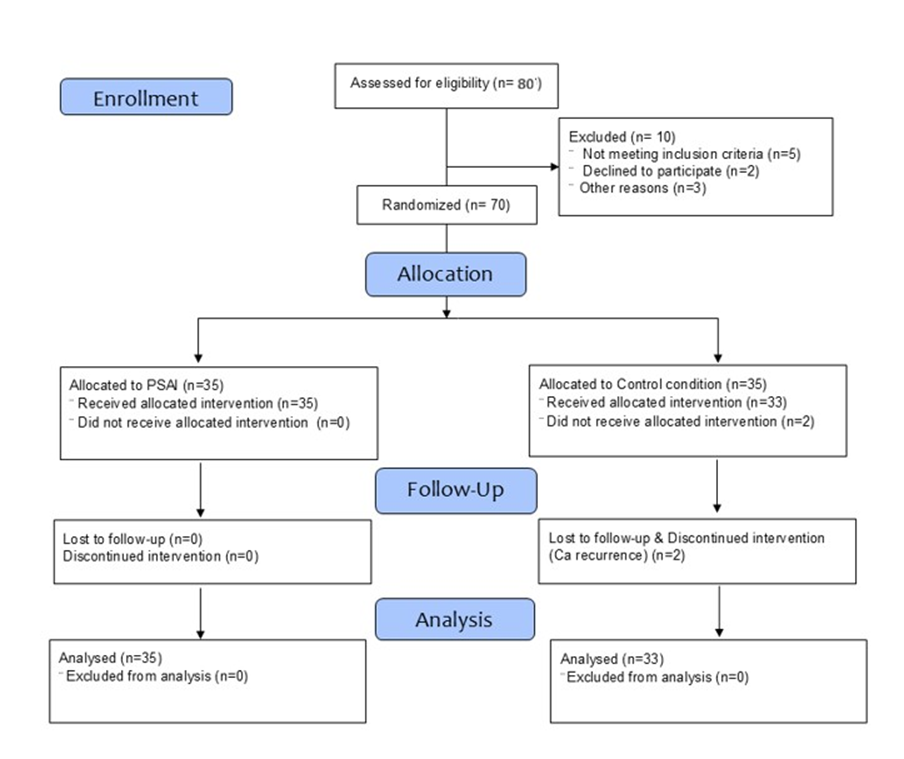

Seventy women were initially enrolled and randomized in a 1:1 allocation ratio, with 35 assigned to the intervention group and 35 to the control group. Two participants in the control group discontinued before follow-up assessment, resulting in 68 participants included in the final analysis (intervention: n=35; control: n=33). The study flow is illustrated in Figure 1. Adherence among intervention participants was complete, confirmed through session attendance and weekly practice logs. No adverse events were reported during the intervention period.

Figure 1: Flow-diagram of the study.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. No statistically significant group differences were observed at baseline. Participants were predominantly middle-aged (mean ± SD: 52.81 ± 8.46 years), the majority were parents (83.8%), had completed 6–12 years of education (57.4%), were employed (77.9%), and reported moderate income satisfaction (54.4%). More than half were non-smokers (57.4%) and abstained from alcohol (55.9%). With respect to disease status, most women were pre-menopausal (66.2%), identified as extended survivors two to five years post-diagnosis (61.8%), and had undergone lumpectomy (64.7%), radiotherapy (85.3%) and chemotherapy (57.4%). Hormonal therapy was ongoing in 73.5% of the sample. At baseline, no significant differences between groups were detected in lifestyle variables, psychological measurements or biological indices, apart from antioxidant capacity, which was significantly higher in the intervention group (p=0.02) as shown in Table 2.

|

Variables |

Intervention group (N=35) |

Control group (N=33) |

p value |

|

|

Age (mean ± SD) |

52.60±8.11 |

53.03±8.94 |

0.84 |

|

|

Parity, n (%) |

Yes |

27 (77.1) |

30 (90.9) |

0.12 |

|

No |

8 (22.9) |

3 (9.1) |

||

|

Educational level, n (%) |

Primary school-High school (6- 12 years) |

23 (65.7) |

16 (48.5) |

0.15 |

|

Higher education (≥14 years) |

12 (34.3) |

17 (51.5) |

||

|

Employment status, n (%) |

Yes |

29 (82.9) |

24 (72.7) |

0.31 |

|

No |

6 (17.1) |

9 (27.3) |

||

|

Income satisfaction, n (%) |

Low |

7 (20.0) |

12 (36.4) |

0.32 |

|

Medium |

21 (60.0) |

16 (48.5) |

||

|

High |

7 (20.0) |

5 (15.2) |

||

|

Smoking behavior, n (%) |

Yes |

15 (42.9) |

14 (42.4) |

0.97 |

|

No |

20 (57.1) |

19 (57.6) |

||

|

Alcohol consumption, n (%) |

Yes |

16 (45.7) |

14 (42.4) |

0.79 |

|

No |

19 (54.3) |

19 (57.6) |

||

|

Menopausal status, n (%) |

Pre-menopausal |

25 (73.5) |

20 (60.6) |

0.26 |

|

Post-menopausal |

9 (26.5) |

13 (39.4) |

||

|

Survivor status, n (%) |

Acute survivors (0-1 years) |

13 (37.1) |

13 (39.4) |

0.85 |

|

Extended survivors (2-5 years) |

22 (62.9) |

20 (60.6) |

||

|

Breast cancer stage, n (%) |

In situ |

2 (5.7) |

0 (0.0) |

0.64 |

|

IA |

13 (37.1) |

13 (39.4) |

||

|

IB |

3 (8.6) |

1 (3.0) |

||

|

IIA |

7 (20.0) |

7 (21.2) |

||

|

IIB |

7 (20.0) |

6 (18.2) |

||

|

IIIA |

1 (2.9) |

1 (3.0) |

||

|

Unknown |

2 (5.7) |

5 (15.2) |

||

|

Surgery type, n (%) |

Lumpectomy |

24 (70.6) |

20 (62.5) |

0.49 |

|

Mastectomy (single/double) |

10 (29.4) |

12 (37.5) |

||

|

Hormonal therapy, n (%) |

Yes |

28 (80.0) |

22 (66.7) |

0.21 |

|

No |

7 (20.0) |

11 (33.3) |

||

|

Radiation therapy, n (%) |

Yes |

31 (88.6) |

27 (81.8) |

0.43 |

|

No |

4 (11.4) |

6 (18.2) |

||

|

Chemotherapy, n (%) |

Yes |

18 (51.4) |

21 (63.6) |

0.31 |

|

No |

17 (48.6) |

12 (36.4) |

||

|

Between-group differences were analyzed by parametric Students’ t-test (categorical by quantitative comparisons) and by Pearson’s chi-square (categorical by categorical comparisons). |

||||

Table 1: Socio-demographic, Health and Disease-related Characteristics of Study Groups.

|

Variables |

Intervention group (N=35) |

Control group (N=33) |

p value |

|

Lifestyle parameters |

|||

|

HLPCQ Total scorea (mean ± SD) |

69.51 ± 9.20 |

68.76 ± 11.68 |

0.77 |

|

PSQI |

5.00 ± 5.00 |

3.00 ± 7.00 |

0.12 |

|

Psychometric parameters |

|||

|

CARS Total score |

61.00 ± 31.00 |

57.00 ± 30.50 |

0.28 |

|

CARS Health worries |

29.00 ± 12.00 |

28.00 ± 14.50 |

0.55 |

|

CARS Role worries |

14.00 ± 11.00 |

13.00 ± 7.50 |

0.15 |

|

CARS Womanhood worriesa (mean ± SD) |

11.80 ± 8.64 |

10.00 ± 8.31 |

0.39 |

|

CARS Death worries |

6.00 ± 5.00 |

6.00 ± 5.00 |

0.58 |

|

PSSa (mean ± SD) |

23.09 ± 8.47 |

22.09 ± 9.06 |

0.64 |

|

DASS Depression |

4.00 ± 5.00 |

3.00 ± 5.00 |

0.56 |

|

DASS Anxiety |

1.00 ± 4.00 |

1.00 ± 2.50 |

0.36 |

|

DASS Stressa (mean ± SD) |

6.17 ± 4.72 |

5.27 ± 3.45 |

0.38 |

|

GSES |

30.00 ± 8.00 |

30.00 ± 8.50 |

0.9 |

|

Biological indexes |

|||

|

Oxidative stress |

67.80 ± 57.10 |

77.77 ± 67.34 |

0.45 |

|

Antioxidant capacity |

312.00 ± 181.00 |

186.00 ± 193.00 |

0.02* |

|

Hair cortisol |

7.96 ± 4.14 |

8.98 ± 5.53 |

0.16 |

|

BMI |

25.20 ± 7.40 |

25.40 ± 5.46 |

0.64 |

|

HLPCQ: Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire, PSQI: Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, CARS: Concerns About Recurrence Scale, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale, DASS: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale, GSES: General Self-Efficacy Scale, BMI: Body Mass Index. Level of significance *p < 0.05. Between-group differences were analyzed by non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (categorical by quantitative comparisons). aBetween-group differences were analyzed by parametric Students’ t-test (categorical by quantitative comparisons). |

|||

Table 2: Baseline Lifestyle, Psychometric and Biological Measurements of Study groups.

Primary Outcomes

Between-group change comparisons are presented in Table 3. A reduction in total fear of cancer recurrence was greater in the intervention group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.104). A similar pattern was observed for Role-related worries (p=0.088) and Death-related worries (p=0.069). A significant improvement was found specifically in Health-related worries, with a larger reduction in the intervention group relative to controls (p=0.034). Womanhood-related worries decreased significantly over time in both groups, but without significant between-group differences (p=0.34).

|

Variables |

Intervention group (N=35) |

Control group (N=33) |

95% CI |

p value |

Effect size |

|

Lifestyle |

|||||

|

ΔHLPCQ Total scorea (mean ± SD) |

12.09 ± 8.53 |

2.09 ± 6.68 |

6.27, 13.72 |

<.001* |

1.3 |

|

ΔPSQIa (mean ± SD) |

-2.54 ± 2.76 |

-0.79 ± 2.62 |

-3.06, -0.45 |

0.009* |

0.65 |

|

Psychometric |

|||||

|

ΔCARS Total score |

-8.00 ± 29.00 |

-4.00 ± 19.50 |

-16.00, 1.00 |

0.104 |

0.2 |

|

ΔCARS Health worries |

-3.00 ± 14.00 |

-1.00 ± 11.0 |

-7.00, 0.00 |

0.034* |

0.26 |

|

ΔCARS Role worries |

-2.00 ± 9.00 |

-0.76 ± 3,94 |

-5.00, 0.00 |

0.088 |

0.21 |

|

ΔCARS Womanhood worries |

-1.00 ± 7.00 |

-1.00 ± 4.50 |

-4.00, 1.00 |

0.034* |

0.08 |

|

ΔCARS Death worries |

-1.00 ± 3.00 |

0.00 ± 1.50 |

-2.00, 0.00 |

0.069 |

0.2 |

|

ΔPSSa (mean ± SD) |

-7.86 ± 6.60 |

-1.82 ± 7.31 |

-9.41, -2.67 |

<.001* |

0.87 |

|

ΔDASS Depression |

-2.00 ± 4.00 |

0.00 ± 3.00 |

-3.00, 0.00 |

0.035* |

0.26 |

|

ΔDASS Anxiety |

0.00 ± 2.00 |

0.00 ± 1.00 |

-1.00, 0.00 |

0.231 |

0.15 |

|

ΔDASS Stress |

-1.00 ± 5.00 |

0.00 ± 4.00 |

-4.00, -1.00 |

0.006* |

0.33 |

|

ΔGSESa (mean ± SD) |

3.66 ± 4.10 |

0.30 ± 4.08 |

1.37, 5.34 |

0.001* |

0.82 |

|

Biological |

|||||

|

ΔOxidative stress |

-11.72 ± 7.06 |

-7.38 ± 12.24 |

-8.09, -0.17 |

0.018* |

0.29 |

|

ΔAntioxidant capacitya (mean ± SD) |

154.57 ± 70.72 |

32.22 ± 49.28 |

92.34, 152.36 |

<.001* |

1.99 |

|

ΔHair cortisol |

-0.52 ± 3.25 |

0.05 ± 3.23 |

-1.05, 1.33 |

0.895 |

0.02 |

|

ΔBMI |

-0.42 ± 0. 74 |

0.15 ± 0.59 |

-0.89, -0.24 |

<.001* |

0.85 |

|

HLPCQ: Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire, PSQI: Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, CARS: Concerns About Recurrence Scale, PSS: Perceived Stress Scale, DASS: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale, GSES: General Self-Efficacy Scale, BMI: Body Mass Index. Level of significance *p < 0.05. Between-group differences were analyzed by non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test (categorical by quantitative comparisons). aBetween-group differences were analyzed by parametric Students’ t-test (categorical by quantitative comparisons). |

|||||

Table 3: Comparisons of Outcomes’ Differences Across Study Groups.

Biologically, oxidative stress decreased significantly more in the intervention group compared with controls (p=0.018), and antioxidant capacity increased substantially in the intervention group (p<0.001). These findings indicate a favorable shift in redox balance following the intervention.

Secondary Outcomes

Significant improvements in lifestyle behavior were observed in the intervention group compared with controls, reflected by increases in total HLPCQ scores (p<0.001) and better sleep quality (p=0.009). Psychological outcomes also demonstrated favorable response to the intervention, with significantly greater reductions in perceived stress (p<0.001), depressive symptoms (p=0.035) and stress scores (p=0.006), alongside increased self-efficacy (p=0.001). Anxiety symptoms did not differ significantly between groups (p=0.23).

Hair cortisol and BMI both decreased in the intervention group only. Between-group comparison revealed a significant reduction in BMI (p<0.001), whereas the decline in hair cortisol did not reach statistical significance (p=0.895).

Discussion

This trial examined the effects of a six-week holistic stressmanagement program incorporating Pythagorean Self-Awareness, lifestyle counselling based on the pillars of Lifestyle Medicine, and relaxation techniques in breast cancer survivors. The intervention produced improvements across psychological, lifestyle, and biological domains, partially confirming our hypotheses and supporting the value of multimodal, integrated approaches during survivorship.

Fear of cancer recurrence declined overall; however, statistically significant between-group differences were observed only in the health-related worry dimension, while womanhood-related concerns decreased similarly in both groups. This pattern suggests that the intervention may have exerted a more targeted effect on health-related cognitive appraisals, potentially through enhanced metacognitive monitoring, self-regulation, and reinterpretation of bodily sensations. The parallel decrease in womanhood-related concerns across both groups may reflect nonspecific therapeutic factors, such as study participation, increased health awareness, or the supportive context of care. Although selective, these effects remain clinically meaningful, given the association between womanhood-related concerns and depressive symptoms [35], as well as the established links between fear of recurrence and maladaptive behavioral patterns including smoking and sleep disruption [36, 37].

Reductions in oxidative stress accompanied by increases in antioxidant capacity were consistent with findings from previous lifestyle-based interventions in breast cancer survivors [38], suggesting that integrated behavioral modification may favorably influence redox homeostasis. These biological changes likely reflect the combined effects of stress reduction, improved sleep, enhanced physical activity, and dietary optimization, all of which are known to modulate reactive oxygen species production and antioxidant defense systems. Interpretation should remain cautious due to baseline differences in antioxidant capacity; nevertheless, the observed pattern supports the concept that psychological stress regulation may translate into downstream biological effects, reinforcing the relevance of lifestyle-oriented interventions as tools for metabolic recovery following treatment [39].

Secondary outcomes further reinforced the global impact of the intervention. Meaningful improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors and sleep quality suggest successful behavioral internalization, an essential prerequisite for sustained health benefits. The observed psychological improvements—namely, reductions in perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and stress reactivity alongside increased self-efficacy—indicate enhanced emotional regulation and coping capacity. These changes are mechanistically relevant, as perceived stress and self-efficacy are key determinants of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activation and long-term physiological stress adaptation. Anxiety remained unchanged, which may reflect the relatively short intervention duration, low baseline anxiety levels, or limited sensitivity of the self-report measures.

The significant reduction in BMI further indicates that cognitive– behavioral restructuring and motivational reinforcement may translate into measurable metabolic changes within a short timeframe. Hair cortisol declined only within the intervention group and did not differ significantly between groups; this is not unexpected, given that hair cortisol reflects cumulative HPAaxis activity over extended time periods and may require longer intervention duration and follow-up to capture robust betweengroup effects [40]. Together, these findings highlight a partial biological embedding of the psychological and behavioral changes induced by the intervention.

Several limitations warrant consideration. The study was not blinded, the sample size was modest, and participants were drawn from a single clinical setting, limiting generalizability. The absence of follow-up assessments precludes conclusions regarding the durability of the observed effects, and reliance on selfreported measures may introduce response bias. Nevertheless, the convergence of improvements across psychological, behavioral, and redox-related outcomes strengthens the interpretation of a genuine intervention effect.

In summary, the findings suggest that a brief, holistic stressmanagement intervention integrating Pythagorean SelfAwareness, lifestyle counseling, and relaxation techniques may exert coordinated effects across emotional, behavioral, and biological stress-regulation pathways in breast cancer survivors. By simultaneously targeting cognitive appraisal, perceived control, health behaviors, and physiological stress systems, such programs may represent a promising complementary strategy within comprehensive survivorship care.

Conclusions

This six-week holistic stress-management intervention, combining Pythagorean Self-Awareness, lifestyle guidance and relaxation techniques, produced improvements in lifestyle behaviours, stress-related psychological outcomes and biological markers of oxidative balance among breast cancer survivors. While effects on overall fear of recurrence were modest, reductions in healthrelated worry, gains in self-efficacy and favourable metabolic shifts suggest that such approaches may enhance well-being during survivorship. Further research using larger randomized cohorts, longer follow-up periods and more rigorous control conditions is needed to validate these findings and determine long-term clinical applicability.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study received no specific funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit agencies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all the women who participated in this study, as well as the nurses and surgeons of the Interdepartmental Breast Unit at the General Hospital “Elena Venizelou” in Athens, Greece.

References

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, et al. (2019) Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 69: 438-451.

- Ciria-Suarez L, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Palacín-Lois M, AntoñanzasBasa M, Fernández-Montes A, et al. (2021) Breast cancer patient experiences through a journey map: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE 16: e0257680.

- Emery J, Butow P, Lai-Kwon J, Nekhlyudov L, Rynderman M, et al. (2022) Management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer. The Lancet 399:1537-1550.

- Simard S, Savard J, Ivers H (2010) Fear of cancer recurrence: specific profiles and nature of intrusive thoughts. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 4: 361-371.

- Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Mutsaers B, Thewes B, et al. (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24: 3265-3268

- Kuswanto CN, Sharp J, Stafford L, Schofield P (2023). Fear of cancer recurrence as a pathway from fatigue to psychological distress in mothers who are breast cancer survivors. Stress Health 39: 197-208.

- Hall DL, Lennes IT, Pirl WF, Friedman ER, Park ER (2016) Fear of recurrence or progression as a link between somatic symptoms and perceived stress among cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 25: 1401-1407.

- Morrissey C, Szuhany K, Malgaroli M, Jennings E, Meyers MI, et al. (2023) Fear of cancer recurrence inventory scores and their correlation with quality of life and stress levels in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 41: e24073–e24073.

- Fenech AL, Soriano EC, Asok A, Siegel SD, Morreale M, et al. (2024) Fear of cancer recurrence and change in hair cortisol concentrations in partners of breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

- Xiong M, Cheng Y, Luo Y, Fang C, Yao H, et al. (2024) The impact of fear of cancer recurrence on the quality of life of breast cancer patients: A longitudinal study of the mediation effect of cortisol and hope. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 70: 102600.

- Yang H, Liu L, Zhang X (2023) Exercise interventions on body composition and quality of life of overweight/obese breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 23.

- Salim S (2014) Oxidative Stress and Psychological Disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol 12: 140-147.

- Ozyurek P, Cevik, C, Kili I, Aslan A (2021). Effects of Day and Night Shifts on Stress, Anxiety, Quality of Life, and Oxidative Stress Parameters in Nurses. Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing 29: 81-92.

- Czerska M, Mikołajewska K, Zieliński M, Gromadzińska J, Wąsowicz W (2015) Today’s oxidative stress markers. Medycyna Pracy 66: 393405.

- Burton GJ, Jauniaux E (2011) Oxidative stress. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 25: 287-299.

- Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Kip KE, Barta M, Ramesar S, et al. (2014) Influence of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Telomerase Activity in Women with Breast Cancer (BC). Biological Research for Nursing 16: 438-447.

- Gurer-Orhan H, Ince E, Konyar D, Saso L, Suzen S (2018). The Role of Oxidative Stress Modulators in Breast Cancer. Current Medicinal Chemistry 25: 4084-4101.

- Nourazarian AR, Kangari P, Salmaninejad A (2014) Roles of Oxidative Stress in the Development and Progression of Breast Cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 15: 4745–4751.

- Gosain R, Gage-Bouchard E, Ambrosone C, Repasky E, Gandhi S (2020) Stress reduction strategies in breast cancer: review of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic based strategies. Semin Immunopathol 42: 719-734.

- Ream, M, Saez-Clarke E, Taub C, Diaz A, Frasca D, et al. (2022). Brief Post-Surgical Stress Management Reduces Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Overweight and Obese Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Primary Treatment. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 27:148.

- Seliniotaki T, Bacopoulou F, Vlachakis D, Artemiadis A, Kampoli K, et al. (2021). Effects of an 8-week stress management program in women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. In P. Vlamos (Ed.), GeNeDis 2020: Adv Exp Med Biol 2021:1339:85-95.

- Charalampopoulou M, Bacopoulou F, Syrigos KN, Filopoulos E, Chrousos GP, et al. (2020) The effects of Pythagorean self-awareness intervention on breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant therapy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. The Breast 49: 210-218.

- Nápoles AM, Santoyo‐Olsson J, Stewart AL, Ortiz C, Samayoa C, et al. (2020) Nuevo Amanecer‐II: Results of a randomized controlled trial of a community‐based participatory, peer‐delivered stress management intervention for rural Latina breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology,29: 1802-1814.

- Lyu M, Siah RC, Lam ASL, Cheng KKF (2022) The effect of psychological interventions on fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Adv Nurs 78: 3069-3082.

- Darviri C, Alexopoulos EC, Artemiadis AK, Tigani X, Kraniotou C, et al. (2014) The Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ): a novel tool for assessing self-empowerment through a constellation of daily activities. BMC Public Health 14: 995.

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research 28: 193-213.

- Kotronoulas GC, Papadopoulou CN, Papapetrou A, Patiraki E (2010). Psychometric evaluation and feasibility of the Greek Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (GR-PSQI) in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 19: 1831-1840.

- Charalampopoulou M, Mantikas V, Laskaridou GE, Georgopoulou A, Daskalakis P, Tryfonopoulos D, Batsis C, Manettas AI, Anastasiou IA, Sideris P, Bacopoulou F, Zagouri F, Zografos GC, Darviri C (2025) Psychometric validation of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS) in a sample of Greek breast cancer survivors. Journal of Oncology Research and Therapy 10:10319. DOI: 10.29011/2574710X.10319.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1995) Perceived stress scale. In S. Cohen, R. C. Kessler, & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford University Press.

- Andreou E, Alexopoulos EC, Lionis C, Varvogli L, Gnardellis C, et al. (2011) Perceived Stress Scale: Reliability and Validity Study in Greece. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8: 3287-3298.

- Lovibond, SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney Psychology Foundation.

- Lyrakos GN, Arvaniti C, Smyrnioti M, Kostopanagiotou G (2011) Translation and validation study of the depression anxiety stress scale in the Greek general population and in a psychiatric patient’s sample. European Psychiatry 26: 1731-1731.

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M, Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M (1995) Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs 35-37.

- Mystakidou K, Parpa E, Tsilika E, Galanos A, Vlahos L (2008) General perceived self-efficacy: validation analysis in Greek cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer 16: 1317-1322.

- Al Harrasi SM, Al-Awaisi H, Al Balushi M, Al Balushi L, Al Kharusi S (2025) Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Its Association with Depressive Symptoms among Adult Omani Female Breast Cancer Survivors. International Journal of Women’s Health 17: 2625-2635.

- Reed SC, Berrett-Abebe J, Whitney RL, Sarkar S, Bell JF (2021) Relationships between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety and worry, and health behaviors and health service use: a systematic review. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology Research and Practice 3: e064.

- Perndorfer C, Soriano EC, Siegel SD, Spencer RMC, Otto AK, et al. (2022). Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Sleep in Couples Coping With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Ann Behav Med 56: 1131-1143.

- Brown JC, Sturgeon K, Sarwer DB, Troxel AB, DeMichele AM, et al. (2023) The effects of exercise and diet on oxidative stress and telomere length in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 199: 109-117.

- Sri Phani Tejaswi P (2022) Oxidative stress in breast cancer after chemotherapy. Bioinformation 18: 1141-1145.

- Stalder T, Kirschbaum Cn(2012) Analysis of cortisol in hair – State of the art and future directions. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 26: 10191029.

- Hauner D, Günther J, Schederecker F, Donik L, Meyer D, et al. (2024) Effect of a comprehensive lifestyle intervention program on body weight and health behavior in women with breast cancer: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr 43:1937-1951.

- Kwak A, Jacobs J, Haggett D, Jimenez R, Peppercorn J (2020) Evaluation and management of insomnia in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 181: 269-277.

- Wang S, Yang T, Qiang W, Zhao Z, Shen A, et al. (2022) Benefits of weight loss programs for breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Supportive Care in Cancer 30: 3745-3760.

- Wright LE, Sudheendra PK (2024) Evidence for the benefits of lifestyle medicine interventions in breast cancer survivorship. The Oncologist 30.

- Yang Y, Qi H, Li W, Liu T, Xu W, et al. (2023) Predictors and trajectories of fear of cancer recurrence in Chinese breast cancer patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 166: 111177.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.