Exploring the Relationship between Dementia Literacy, Acculturation, Social Networks, and Help-Seeking Behaviour: A Cross-Sectional Study

by Koduah Adwoa Owusuaa1, Leung Angela Yee Man1,2*, Leung Sau Fong¹, Cheung Teris¹

¹School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

²Research Institute of Smart Ageing (RISA), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China

*Corresponding author: Leung Angela Yee Man, School of Nursing, Research Institute of Smart Ageing (RISA), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China

Received Date: 19 August, 2025

Accepted Date: 25 August, 2025

Published Date: 30 August, 2025

Citation: Owusuaa KA, Yee Man LA, Fong LS, Teris C (2025) Exploring the Relationship between Dementia Literacy, Acculturation, Social Networks, and Help-Seeking Behaviour: A Cross-Sectional Study. Advs Prev Med Health Care 8: 1079. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-996X.001079

Abstract

Objective: Delays in seeking dementia care hinder early diagnosis and management, especially among migrant populations. Factors such as limited dementia literacy, restricted social networks, and acculturation challenges may influence help-seeking behaviours, but their precise relationships remain unclear. This study examines the associations between dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia among Africans living in Hong Kong. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted using purposive and snowball sampling to recruit participants between October and December 2021. Descriptive statistics, Spearman correlation analyses, and structural equation modelling were used to analyse the data. Results: A total of 461 Africans (mean age 33.5 years) participated. Significant associations were found between intention to seek help and social networks (β = 0.09, p = 0.021), assimilation (β = 0.16, p < 0.001), and dementia literacy (knowledge of how to access dementia information; β = -0.16, p < 0.001). Knowledge of how to access dementia information partially mediated the relationships between social networks and help-seeking intention, as well as between acculturation and help-seeking intention. Conclusion: These findings highlight the need to strengthen social networks and improve awareness of dementia resources within the community. Enhancing access to dementia in-formation and supporting effective assimilation strategies may encourage proactive help seeking among Africans in Hong Kong. Future interventions should focus on these areas to better support this population in navigating dementia care.

Keywords: Acculturation; Dementia literacy; Ethnic minority groups; Help-seeking behaviour; Social network.

Introduction

The influx of thousands of Africans into China has added a new cohort to healthcare and medical services. Recent research confirms this in places such as Hong Kong [1,2]. The number of older adults in the African migrant population in China’s megacities such as Hong Kong is expected to rise, and many of them are likely to develop dementia (Television Broadcast Ltd (2012). Recent studies have shown that the prevalence of dementia among people of African descent is greater than that among people of any other ethnic group and that this group experiences a much earlier onset of dementia [3,4]. Timely diagnosis of dementia is imperative among this population. According to the World Health Organisation, an estimated 55 million people were living with dementia in 2022, and dementia was the 7th leading cause of dependency, disability and mortality globally (World Health Organization, 2022). Dementia burdens the sufferer and considerably burdens caregivers, family members, and society [5]. However, people of African descent have been reported to present late for dementia diagnosis for various reasons [6]. These include inadequate dementia literacy (i.e., normalisation of memory problems, the belief that families rather than services are the appropriate resource, dementia-related stigma), experiences with health services, language barriers, and cultural factors, which include social network and acculturation issues [7, 8]. Low and Anstey [9] defined dementia literacy (DL) as “knowledge and beliefs regarding dementia that aid recognition, management, and prevention of the condition.” Recently, Nguyen et al. [5] suggested expanding this definition to encompass descriptive dimensions such as the nature of the condition; its causes; risk factors; symptoms; and the processes of recognition, management, and prevention.

In this study, dementia literacy is operationalised as the knowledge of symptoms, causes, risk factors, and available services that facilitate the recognition, management, and prevention of dementia. An adequate level of dementia literacy includes early diagnosis, improved understanding of the disease’s trajectory, and effectiveness in addressing dementia-related issues, such as early helpseeking, diagnosis, and advance care planning [5,10]. Despite this relatively attainable list of responses to the disease, there is an inadequate level of dementia literacy among the general population and even health professionals in both developed and developing countries [11,12]. Moreover, inadequate dementia literacy among the public has been found to lead to social discomfort, negative attitudes, stigmatisation, a lack of help seeking and the abuse of persons with dementia.

This attitude was found to prevail even among family members, who often feel obliged to care for patients with dementia openly [13,14]. Beliefs about dementia among people of African descent and other minority groups often encompass several perceptions, including the notion that dementia is primarily a condition associated with white populations [7,15]. Additionally, there is a tendency to view dementia as a normal aspect of aging [13]. Furthermore, some individuals may attribute the onset of dementia to spiritual factors, such as the ‘evil eye,’ curses, or witchcraft [13]. These beliefs can significantly influence help-seeking behaviour and the overall understanding of dementia within various African communities [7].

In addition to the factors that directly influence the decision to seek dementia care, migration presents its own set of challenges. Migration often leads to the disruption of family and social ties, resulting in limited social interactions and increased social isolation for migrants in their new environments [8]. This issue is particularly concerning for people of African descent, who typically rely on their social networks for health information, care, and decision-making. Mental health conditions, including dementia, are frequently stigmatised in various African cultures. Consequently, many African families may hesitate to seek help, often concealing or delaying assistance for relatives with dementia due to concerns about discrimination, familial obligations to care for older adults, and the fear of stigma [7,13].

Numerous studies have established a relationship between social support and help-seeking behaviour [16,17,18]. However, there remains a gap in the literature regarding how family dynamics specifically influence dementia care and help-seeking behaviours among migrant Africans. Furthermore, alongside the disruptions in social ties, migrants must navigate the significant challenge of acculturating to their new society, which can further complicate their access to necessary care and support. Acculturation has been defined as a complex process by which an individual incorporates a host group’s cultural patterns through immigration [19,20].

The level of acculturation has been associated with various health beliefs and practices among ethnic minorities and people from low- and middle-income countries [19,21]. Studies have suggested that the greater an individual’s acculturation level is, the greater his or her exposure to biomedical or Western ideologies about various health conditions, as well as his or her awareness of health services and the likelihood of receiving accurate health information [8]. Among Asian Americans, a lower level of acculturation is associated with less exposure and poorer knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and delayed diagnosis [21]. However, none of these studies focused on acculturation and dementia-related issues among African migrants or people of African descent living in Western or Eastern societies.

The studies that do examine acculturation and health issues focus only on health literacy as a whole, with few studies focused on dementia literacy, with the majority of these studies from Western societies. No study has focused solely on acculturation and dementia help-seeking behaviour or dementia literacy. Little is known about how acculturation to Eastern cultures such as Hong Kong may impact dementia literacy. According to the sociocultural health belief model (SHBM), dementia knowledge, acculturation, and family-centered cultural values directly affect the decision to seek dementia care [21]. However, no study has examined the relationships among dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia among Africans living in Eastern society. This study is the first to explore the relationships between these factors and the intentions of African migrants in Hong Kong to seek help for dementia. To this end, this study has examined the relationships among dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia among Africans living in Hong Kong. The specific questions for this study were as follows:

- What is the preferred source of help for dementia among Africans living in Hong Kong?

- Do dementia literacy, acculturation, and social networks affect Africans’ intentions to seek help for dementia?

- Does dementia literacy mediate the relationship between acculturation and the intention to seek help for dementia or the relationship between social networks and the intention to seek help?

Methods

This is a cross-sectional survey that uses convenient and snowball sampling techniques. The study was approved by the Human Subject Ethics Subcommittee of Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Reference Number: HSEARS20200907003).

Setting

The study was conducted in Hong Kong, and participants were recruited from various places within and around Central China, Tsim Sha Shui (Chungking & Mirador Mansions), Sham Shui Po, Yuen Long, Long Ping, Tuen Mun, Wan Chai, and East Tsim Sha Tsui. These recruitment sites were selected because previous studies reported that these were the places where most Africans carried out their daily lives and ran their trading businesses [1,22, 23].

Sample and Sample Size

Africans who were actually living in Hong Kong between October and December 2021 were recruited as part of the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adults aged 18 years and above; (2) African who had lived in Hong Kong for at least two years; and (3) could speak and read English. The exclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) had severe difficulty communicating; (2) had visual or hearing impairments. The sample for the study was calculated via the sample size calculator.net, which is based on a confidence level of 95%, a ±5% margin of error, a population proportion of 50% and a population size of 4000. The calculated results indicated that a minimum total sample size of 351 was needed. Considering an attrition rate of 20%, the total sample size was increased to 421.

Data Collection

A purposive and snowball sampling approach was employed to recruit Africans living in Hong Kong. Given that this population is often considered hard to reach, the snowball sampling technique facilitated the recruitment process by leveraging the social networks of initial participants to identify and engage additional respondents across various locations in Hong Kong. To streamline access to the study, a QR code linked to the questionnaire hosted on Qualtrics was generated and included on the registration poster for the study. Additionally, recruitment was conducted through WhatsApp and Facebook pages dedicated to various African communities, further enhancing outreach efforts. Face-to-face recruitment also occurred, during which participants were invited to scan the QR code to access the questionnaire directly.

An initial set of screening questions was incorporated into the questionnaire to ensure the eligibility of the participants. Upon the commencement of the survey, the participants were required to sign a consent form; only those who agreed to participate were granted access to the full questionnaire. The purpose of the study and the procedures involved were clearly articulated at the beginning of the survey, with written consent obtained on the first page. In instances where participants chose not to complete the survey, they logged out of the system to maintain data integrity.

Theoretical Framework

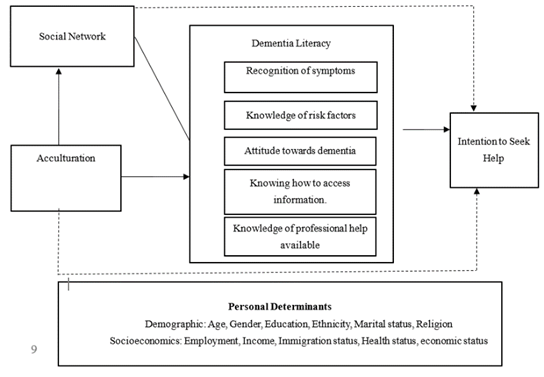

The Sociocultural Health Belief Model (SHBM) and the Integrated Health Literacy Model serve as the theoretical frameworks for this study. The SHBM is an adaptation of the health belief model (HBM), originally developed by Sayegh and Knight [21]. The HBM is widely recognised as the predominant model for assessing factors that facilitate or hinder help-seeking behaviour for dementia-related issues. While the HBM has proven effective in identifying determinants that influence dementia care-seeking behaviour, it initially lacked explicit consideration of various sociocultural factors that may play a critical role in this context.

To address this limitation, Sayegh and Knight [21] revised the HBM by incorporating essential social determinants, including acculturation, cultural beliefs, knowledge about dementia, and family-centered cultural values. This revision enhances the model’s explanatory power by recognising that help-seeking behaviour is not solely an individual decision but is significantly influenced by sociocultural context.

In parallel, Sorensen et al. [24] developed the Integrated Health Literacy Model following a comprehensive review of existing health literacy frameworks. This model encompasses four key competencies: accessing, appraising, understanding, and applying health information. Furthermore, it identifies various factors that influence health literacy, categorising them into personal, situational, and societal/environmental determinants. Within this framework, acculturation is conceptualised as an environmental determinant, whereas the social network serves as a situational determinant. The personal determinants include age, gender, ethnicity (race), occupation, income, employment status, socioeconomic status, length of stay in Hong Kong, and immigration status. The acculturation and social network of Africans reflect the broader cultural context in which they navigate their help-seeking behaviours.

Study Hypotheses

On the basis of the sociocultural help-belief model, the mental health literacy model, and empirical studies, the following hypotheses were tested:

- Higher levels of dementia literacy, acculturation, and social networks are positively associated with the intention to seek help for dementia.

- Dementia literacy mediates the relationship between acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia

Measures

Dependent Variable

The intention to seek help was measured via the General HelpSeeking Questionnaire (GHSQ) [25]. The GHSQ consists of eight items, with six items describing different sources of help-seeking, such as spouses, friends, parents, phone helplines, religious leaders (pastors, imams, and traditional healers), and health professionals (including general practitioners, psychiatrists, social workers, and nurses). The last two items, “I would not seek help from anyone” and “I would delay help seeking for as long as possible”, were reverse scored.

Figure 1: Hypothesised model of the relationship between dementia literacy, social network, acculturation, and help-seeking behaviour.

The GHSQ is measured with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely unlikely” to “extremely likely”. Total scores were computed by summing all the responses from each item, with higher scores indicating the intention to seek help. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.68 in this study.

Independent Variables

The Dementia Literacy Scale (DLS) is a 37-item questionnaire developed by the project team with reference to the mental health literacy scale to assess levels of dementia literacy. It comprises five subscales, including recognition of symptoms (8 items), knowledge of risk factors (8 items), knowing how to access information (4 items), knowledge of professional help available (5 items) and attitudes towards dementia (12 items). Responses to the scale were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “5 being strongly agree” to “1 being strongly disagree”. Eight items (items 1, 16, 17, 30, 31, 32, 33 and 37) were reverse scored. The total score is a summation of all the items on the scale. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the DLS scale was 0.96. The complete questionnaire is shown in the supplementary file.

Acculturation was measured via the eight-item brief acculturation orientation scale (BAOS) [26]. The questionnaire consisted of two independent subscales (orientation to home and host cultures). This study adapted the host culture subscale to refer to Hong Kong culture. The central indicators (friendships, traditions, actions, and characteristics) of acculturation were presented twice (e.g., “It is important for me to have [Hong Kong] [African] friends”). Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Extremely important (5)” to “Not at all important (1)”. Total scores were computed by summing all the responses from each item. The scale had acceptable internal consistency reliability, with α= 0.90 (African culture) and α= 0.91 (Hong Kong culture). The total score was computed by summing positive-scored items (assimilation and integration) and reversed negative items (separation and marginalisation).

The social network score of the participants was measured via the short version of the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) [27]. The LSNS-6 consists of six items rated on a 6-point Likert scale with none= 0, one = 1, two = 2, three or four = 3, five through eight = 4, and nine or more = 5. The LSNS-6 was conceptualised as having two dimensions: family and friends. Scores ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores (> 12) indicating high social networks and lower scores (< 12) indicating social isolation. In this study, the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.69, indicating acceptable internal consistency reliability.

Covariates

Sociodemographic data collected included age, gender, education, employment status, immigration status (Hong Kong resident, permanent resident, asylum seeker, refugee, and diplomat), marital status, religion, health status (physical and mental status), economic status, and length of stay in Hong Kong. The average time for completing all questionnaires was 10 minutes.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to describe the participants’ characteristics and the main variables. Spearman correlation analyses were conducted to determine the relationships between intentions to seek help for dementia, dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and covariates (gender, age, education, marital status, employment, duration of stay, immigration status, religion, physical health status and mental health status).Structural equation models were constructed to estimate the relationships among dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia. The model used the significant predictors identified from the correlation analysis. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the model parameters. Standardised regression coefficients were utilised to evaluate the effects of dementia literacy, acculturation, and social networks on help-seeking behaviour. The overall fitness of the model was assessed via the chi-square ratio to the degree of freedom (χ2/df), the root means square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis index (TLI), the normed fit index (NFI), the model chi-square (p) and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). For goodness-offit indices, the following values were considered acceptable: χ2/df ≤ 2, RMSEA < .08, p> 0.05 and SRMR < .08, and the CFI, IFI, and TLI cut-off scores should be above 0.9 (Meyers et al., 2016; Thakkar, 2020). Statistical analyses were performed via IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, 2013) and AMOS [28].

Results

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

A total of 461 participants completed the survey. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants. The majority of the participants were males (71.8%), were born in Africa (95.2%), had a bachelor’s degree (61%), and were Christians (72.5%). More than half were employed (57.5%). With respect to immigration status, more than half of the participants were Hong Kong residents (working or student visas) from October to December 2021 (60.7%) and had lived there for an average of 6.6 years (SD=5.42). Except for Morocco, Algeria and Egypt, there was at least one participant from the remaining African countries. Most participants rated their physical health status as good (86.3%) but reported poor mental health status (58.4%).

|

Demographic

characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

331 |

71.8 |

|

Female |

130 |

28.2 |

|

|

Age |

18 - 24 years |

52 |

11.3 |

|

25 – 34 years |

22 |

48.2 |

|

|

35 – 44 years |

134 |

29.1 |

|

|

45 - 59 years |

52 |

11.3 |

|

|

60 years and above |

1 |

0.2 |

|

|

Education |

Primary school |

3 |

0.7 |

|

Junior Secondary School |

12 |

2.6 |

|

|

Senior Secondary School + Vocational Training |

61 |

13.2 |

|

|

Diploma/Associate |

55 |

11.9 |

|

|

Degree |

|||

|

Bachelor's degree |

281 |

61 |

|

|

Doctoral Degree |

49 |

10.6 |

|

|

Marital status |

Married |

228 |

49.5 |

|

Divorced |

24 |

5.2 |

|

|

Single/Never married |

209 |

45.3 |

|

|

Employment |

Employed |

265 |

57.5 |

|

Unemployed |

46 |

10 |

|

|

Students |

150 |

32.5 |

|

|

Duration of stay |

2 – 5 years |

275 |

59.7 |

|

6 – 10 years |

110 |

23.9 |

|

|

11 – 15 years |

30 |

6.5 |

|

|

16 – 20 years |

33 |

7.2 |

|

|

21 years and above |

13 |

2.8 |

|

|

Immigration status |

Permanent resident |

134 |

29.1 |

|

Hong Kong residents |

280 |

60.7 |

|

|

Asylum seekers |

28 |

6.1 |

|

|

Refugees |

17 |

3.7 |

|

|

Diplomatic Visa |

2 |

0.4 |

|

|

Religion |

Christian |

334 |

72.5 |

|

Muslim/Islam |

105 |

22.8 |

|

|

No religion |

22 |

4.8 |

|

|

Physical Health |

Poor (1-5) |

63 |

13.7 |

|

Good (6-10) |

398 |

86.3 |

|

|

Mental health |

Poor (1-5) |

269 |

58.4 |

|

Good (6-10) |

192 |

41.6 |

|

|

Economic status |

Low (scale 1-5) |

293 |

63.6 |

|

High (6-10) |

168 |

36.4 |

|

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the participants.

Descriptive Statistics for the Main Variables

The mean score for the intention to seek help for dementia was 32.25 (SD=4.03), which indicated that participants were likely to seek help if they thought they were experiencing early signs and symptoms of dementia. A majority of the participants preferred to seek help from health professionals (M=4.57, SD=.93) and parents (M=4.54, SD=.87), with fewer preferring to seek help from a friend (M=3.16, SD=1.35) or a religious leader (M=3.57, SD=1.44). The dementia literacy (M = 87.27, SD= 36.14) of the participants was generally inadequate. There were lower scores on all five subscales of the dementia literacy questionnaire. On the other hand, the total mean score for acculturation was 20.58 (SD= 5.69), and there was no significant difference in acculturation strategies: integration (29.7%), assimilation (26.7%), separation (22.1%) and marginalisation (21.5%). The mean total score for social networks was 14.59 (SD=4.45), the mean score for friends’ networks was 6.26 (SD=3.2), and that for the family network was 8.33 (SD=2.7).

Factors Associated with the Intention to Seek Help for Dementia

Table 2 shows the relationships between intentions to seek help, dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and sociodemographic variables. None of the covariates in this study correlated with help-seeking behaviour. The intention to seek help was positively associated with a social network (total score) (r = .114, p = 0.014) but was not significantly related to dementia literacy (r = .024, p = 0.609) or acculturation (r=.023, p=0.621). Assimilation orientation strategy (r = .13, p = 0.007), friends’ subscale (social network) (r = .11, p = 0.016) and knowledge of how to access information (dementia literacy subscale) (r = -.13, p = 0.007) were associated with the intention to seek help. The remaining subscales showed no significant relationship with the intention to seek help for dementia.

Path analysis was conducted to assess the mediating effect of dementia literacy on the relationships among acculturation, social networks, and the intention to seek help for dementia.

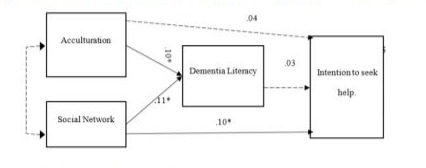

Figure 2 shows that only social networks (β = 0.10, p = 0.029) were positively correlated with the intention to seek help. Dementia literacy (β = 0.03, p=0.472) and acculturation (β = 0.04, p=0.429) were not correlated with the intention to seek help. The analysis revealed that dementia literacy does not mediate the relationships among social networks, acculturation, or the intention to seek help. Nonetheless, social network (β = 0.11, p=0.021) and acculturation (β = 0.10, p=0.027) have a significantly positive connection with dementia literacy. The hypothesised model (Figure 2) demonstrated a moderate model fit (CMIN= .120; NFI= 0.99; TLI=1.51; CFI=1.00; RMSEA ≤ 0.001, X²/df=.120; P=0.729; df=1.).

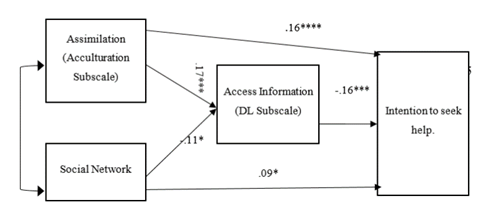

Figure 3 shows the final model. Assimilation (β = 0.16, p<0.001) and social networks (β = 0.09, p=0.021) show that there is a significant positive relationship between assimilation and social work with the intention to seek help, whereas knowledge of how to access dementia information (β = -0.16, p<.001) has a significantly negative relationship with the intention to seek help. Assimilation (β = 0.17, p<.001) (which is a subscale of acculturation) and social networks (β = -0.11, p<.014) demonstrate a significantly positive and adverse relationship between these two variables and knowing how to access information, respectively. The model demonstrated good model fit (CMIN= .723; NFI= 0.99; TLI=1.00; CFI=1.00; RMSEA=0.001, X²/df=.723; P=0.395; df=1.) and explained 4% and 5% of the variance in access to information and the intention to seek help, respectively.

|

HS |

DL |

DL1 |

DL2 |

DL3 |

DL4 |

DL5 |

SN |

SN1 |

SN 2 |

ACC |

ACC1 |

ACC2 |

ACC3 |

ACC4 |

|

|

HS |

1 |

0.024 |

0.054 |

0.029 |

-.126** |

0.042 |

0.059 |

.114* |

0.045 |

.112* |

0.023 |

-0.028 |

.125** |

-0.041 |

-0.062 |

|

DL |

1 |

.885** |

.901** |

0.033 |

.588** |

.878** |

0.043 |

-0.037 |

.121** |

.092* |

.130** |

.156** |

-.232** |

-0.079 |

|

|

DL1 |

1 |

.823** |

-.131** |

.469** |

.788** |

.163** |

0.076 |

.203** |

.117* |

.151** |

0.088 |

-.193** |

-0.067 |

||

|

DL2 |

1 |

-.121** |

.538** |

.786** |

0.055 |

-0.006 |

.104* |

0.075 |

.112* |

.143** |

-.201** |

-0.075 |

|||

|

DL3 |

1 |

-.307** |

-0.08 |

-.140** |

-.155** |

-0.05 |

-0.027 |

0.033 |

.184** |

-.208** |

-0.025 |

||||

|

DL4 |

1 |

.439** |

-0.002 |

-0.011 |

0.001 |

.105* |

.094* |

-0.019 |

-0.034 |

-0.05 |

|||||

|

DL5 |

1 |

.096* |

0.006 |

.158** |

.101* |

.153** |

.134** |

-.239** |

-0.073 |

||||||

|

SN |

1 |

.701** |

.806** |

-0.02 |

-0.002 |

-0.022 |

0.028 |

-0.001 |

|||||||

|

SN1 |

1 |

.195** |

-0.025 |

-0.029 |

-0.035 |

0.071 |

-0.002 |

||||||||

|

SN2 |

1 |

0.023 |

0.053 |

-0.005 |

-0.036 |

-0.017 |

|||||||||

|

ACC |

1 |

.655** |

-0.011 |

-0.032 |

-.685** |

||||||||||

|

ACC1 |

1 |

-.392** |

-.347** |

-.340** |

|||||||||||

|

ACC2 |

1 |

-.322** |

-.315** |

||||||||||||

|

ACC3 |

1 |

-.279** |

|||||||||||||

|

ACC4 |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

** p value < 0.01, * p value < 0.05 level. Abbreviations: HS=Help seeking, DL= Dementia literacy; SN= Social network, ACC = Acculturation. The subscales of DL include D1= recognition, D2= risk factors, D3= knowledge of how to access information, D4= professional help, and D5= attitudes. The SN subscales include SN1= Family Network and SN2= Friends Network. The subscales of the ACC include ACC1= integration, ACC2= assimilation, ACC3= separation, and ACC4= marginalisation. |

|||||||||||||||

Table 2: Spearman’s correlation analysis between help-seeking behaviour and dementia literacy, acculturation, and social networks.

Figure 2: The hypothesised model for the study.

Figure 3: Final Model for the study.

Note: Estimates are standardised estimates. *p<.001, ** p< 0.01, * p< 0.05.

The Mediating Effect of Knowledge of How to Access Information

The mediating effect of “knowledge of how to access information” (dementia literacy subscale) is presented in Table 3. Knowledge of how to access information has a significantly partial negative effect (β =- 0.03, p = 0.009) on the relationship between assimilation and help-seeking behaviour.

|

Model Pathway |

Effect |

β |

SE. |

p |

|

Social Network--> Intention to seek help |

Total |

0.11 |

0.05 |

0.033 |

|

Direct |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

|

|

Indirect |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.009 |

|

|

Assimilation--> Intention to seek help |

Total |

0.13 |

0.05 |

0.004 |

|

Direct |

0.16 |

0.05 |

0.001 |

|

|

Indirect |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

0.003 |

|

|

Note: Coefficients are standardised; S.E.= standard error. |

||||

Table 3: Mediating effect of knowledge on how to access information on the relationship between social network assimilation and help-seeking behaviour.

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the factors that influence dementia help-seeking behaviour among ethnic minorities (Africans) living in Hong Kong. These factors included dementia literacy, acculturation (adaptation to Hong Kong culture) and support they receive through their social network while living in Hong Kong.

Help seeking is a complex and dynamic process that is influenced by numerous factors, including quality of life, access to and cost of healthcare services, health and understanding of health behaviour Persons with dementia more often depend solely on caregivers for physical, psychological, and financial support and for decision making, causing an enormous burden on informal caregivers [29]. To ease this burden, most researchers and health professionals have advocated for early help seeking, diagnosis and support. Research into the barriers to help-seeking for patients with dementia has recommended improving dementia literacy (knowledge, awareness, attitudes and access to services) among health professionals and the public as a means to mitigate delays in help-seeking and facilitate early diagnosis [30].

However, the findings from this study prove that the possession of dementia literacy does not imply that one may seek help for dementia. In this study, while access to dementia information is generally perceived as beneficial, among Africans living in Hong Kong, it can negatively predict their help-seeking behaviour. A plausible explanation may be found in studies among Black Africans and Caribbeans in the United Kingdom, which identified that, among this population, fear of negative consequences (stigma, hospitalisation and anticipated discrimination) and the perception that seeking medical care/help for dementia from health professionals is a waste of clinician time were factors that hinder help-seeking or the intention to seek help for dementia even in the case of access to dementia services [7,15,31]. Improving access to dementia information should be considered on a contextual basis, as it could negatively impact help-seeking behaviour through factors such as cultural influences, health system-related factors and misalignment of information. Therefore, an understanding of these dynamics can inform strategies to encourage more proactive helpseeking behaviours.

Similar to previous studies, African families’ and friends’ social networks facilitated help seeking for dementia [30,31].Families play crucial roles in help-seeking and healthcare decision making among people of African descent [32]. There is a shared strong family value of taking responsibility for the care, respect and protection of older family members and keeping secrecy with respect to illnesses in the family within various African cultures. Research has shown that in situations where access to formal services is limited, most Africans living in the diaspora often rely on social networks (friends, family and community) for immediate support [31]. This practice of familism may serve as a deterrent to accessing services for dementia within the community. Therefore, this study recommends that fostering strong, supportive relationships within a community can play an integral role in encouraging minority groups to pursue care and treatment. This highlights the importance of community engagement with ethnic groups and support systems to promote proactive help-seeking behaviours [33-36].

In contrast to previous studies, our research revealed that overall acculturation was not significantly associated with help-seeking behaviour for dementia [21]. However, further analysis revealed that Africans who maintain their cultural heritage while adopting the cultural beliefs and norms of their host society-an assimilation strategy-exhibit a greater intention to seek help for dementia than do those who do not [37,38]. As Africans assimilate Hong Kong society, they may become more familiar with local customs, dementia care practices, and available resources and services. This increased familiarity can enhance their understanding and awareness of dementia care options, ultimately facilitating a greater intention to seek help. These findings suggest that while general acculturation may not directly influence help-seeking behaviour, a strategic approach to assimilation that incorporates both cultural heritage and host society norms can positively impact individuals’ willingness to seek necessary care [40-43]. Future studies should investigate how cultural assimilation impacts help-seeking behaviours across diverse populations. An understanding of the nuances of cultural identity and its relationship with dementia care and services can inform nursing education and practice.

Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

The cross-sectional design restricted the ability to infer causal relationships among dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and help-seeking behaviour. Therefore, a longitudinal study is recommended for investigating causality [44,45]. Caution should be taken in making conclusive associations regarding some findings from the survey. In addition, this study assessed only the intention to seek help for dementia patients and did not assess actual helpseeking behaviour. Further studies are needed to examine the associations among dementia literacy, acculturation, social networks, and active help-seeking behaviour. The study’s focus on Hong Kong may limit the applicability of the findings to other countries where cultural, social and healthcare dynamics may differ significantly [46]. The unique cultural context of Hong Kong may influence help-seeking behaviours in ways that are not applicable to other multicultural environments.

Implications of the Study

Policy makers should promote interventions/initiatives that facilitate the integration of ethnic minorities into healthcare systems [47-49]. This may include funding for community-based outreach programs that foster networks and encourage help-seeking behaviours. Health professionals should actively engage with communities to build trust and strengthen social networks. By understanding the cultural backgrounds of their patients, health professionals can provide more personalised care and encourage proactive helpseeking behaviours. Nursing education programs should emphasise the importance of cultural competence, focusing on how to address the unique needs of diverse populations regarding dementia care.

Conclusion

This study revealed significant relationships among access to information (dementia literacy subscale), assimilation, social networks, and help-seeking behaviour among Africans living in Hong Kong [50]. The findings emphasise that merely improving dementia literacy may not sufficiently address delays or the lack of help-seeking behaviour. It is crucial to consider contextual factors such as social networks and acculturation in these efforts. Integrating Africans into Hong Kong society is imperative, yet evidence indicates that many Africans face racism, discrimination, and stereotyping during their acculturation process. Sensational media portrayals have contributed to the perception that Africans are inferior to Hong Kong residents [22,23]. Consequently, the Hong Kong government has a moral and ethical obligation to combat intolerance, foster respect for diversity, and establish social and community support systems that facilitate better integration for Africans [51]. This approach is essential for enhancing the process of acculturation and improving overall help-seeking behaviour for dementia care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, AOK, AYML and TC; methodology, AOK, AYML and TC; formal analysis, AOK, AYML and TC; investigation, AOK; data curation, AOK; writing-original draft preparation, AOK, AYML, TC and SFL; writing-review and editing, AOK, AYML, TC and SFL; supervision, AYML, TC and SFL All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the PolyU Research Postgraduate Scholarship and Teaching Postgraduate Studentship (TPS) Scheme. However, this study received no external funding from any public funding agency.

Acknowledgements

The authors are highly grateful to the leaders of the African Community and participants for their support and willingness to participate in the study.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Availability of Data and Materials

The dataset from this study will be made available by request from corresponding author.

References

- Amoah PA, Koduah AO, Anaduaka U, Adage EA, Gwenzi GD, et al. (2020a) Psychological Wellbeing in Diaspora Space: A Study of African Economic Migrants in Hong Kong. Asian Ethnicity. 21: 1-18.

- Hall BJ, Chen W, Latkin C, Ling L, Tucker JD (2014) Africans in South China Face Social and Health Barriers. The Lancet. 383: 1291-1292.

- World Health Organisation (2019) Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines.

- World Health Organisation (2021b) Towards A Dementia-Inclusive Society: WHO Toolkit for Dementia-Friendly Initiatives (Dfis).

- Nguyen H, Phan HT, Terry D, Doherty K, Mcinerney F (2022) Impact of Dementia Literacy Interventions for Non-Health-Professionals: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging & Mental Health. 26: 442456.

- Mukadam N, Cooper C, Basit B, Livingston G (2011) Why Do Ethnic Elders Present Later to UK Dementia Services? A Qualitative Study. International Psychogeriatrics. 23: 1070-1077.

- Berwald S, Roche M, Adelman S, Mukadam N, Livingston G (2016) Black African and Caribbean British Communities’ Perceptions of Memory Problems: “We Don’t Do Dementia”. Plos One. 11: e0151878.

- Kovaleva M, Jones A, Maxwell CA (2021) Immigrants and Dementia: Literature Update. Geriatric Nursing. 42: 1218-1221.

- Low LF, Anstey KJ (2009) Dementia Literacy: Recognition and Beliefs on Dementia of the Australian Public. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 5: 4349.

- Leung AYM, Molassiotis A, Zhang J, Deng R, Liu M, et al. (2020) Dementia Literacy in The Greater Bay Area, China: Identifying the At-Risk Population and the Preferred Types of Mass Media for receiving Dementia Information. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17: 2511.

- Smith GD, Ho KHM, Lee A, Lam L, Chan SWC (2022) Dementia Literacy in an Ageing World. Journal Of Advanced Nursing. 76: 2167-2174.

- Zhao W, Jones C, Wu MLW, Moyle W (2022) Healthcare Professionals‘ Dementia Knowledge and Attitudes towards Dementia Care and Family Carers‘ Perceptions of Dementia Care in China: An Integrative Review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 31: 1753-1775.

- Brooke J, Ojo O (2020) Contemporary Views on Dementia as Witchcraft in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 29: 20-30.

- Leung AYM, Leung SF, Ho GWK, Bressington D, Molassiotis A, et al. (2019) Dementia Literacy in Western Pacific Countries: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 34: 18151825.

- Roche M, Mukadam N, Adelman S, Livingston G (2018) The Idemcare Study-Improving Dementia Care in Black African and Caribbean Groups: A Feasibility Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 33: 1048-1056.

- Barker G (2007) Adolescents, Social Support and Help-Seeking Behaviour: An International Literature Review and Programme Consultation with Recommendations for Action.

- Jones N, Greenberg N, Phillips A, Simms A, Wessely S (2019) Mental Health, Help-Seeking Behaviour and Social Support in The UK Armed Forces by Gender. Psychiatry. 82: 256-271.

- Maiuolo M, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J (2019) Parental Authoritativeness, Social Support and Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems in Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 48: 1056-1067.

- Berry JW (2005) Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 29: 697-712.

- Satia-Abouta J, Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Elder J (2002) Dietary Acculturation: Applications to Nutrition Research and Dietetics. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 102: 1105-1118.

- Sayegh P, Knight BG (2013) Cross-Cultural Differences in Dementia: The Sociocultural Health Belief Model. International Psychogeriatrics. 25: 517-530.

- Chow-Quesada S, Tesfaye F (2020) (Re) Mediating ‚Blackness‘ in Hong Kong Chinese Medium Newspapers: Representations of African Cultures in Relation To Hong Kong. Asian Ethnicity. 21: 384-406.

- Zheng M, Leung R (2018) Is Hong Kong Racist? Prejudice against Ethnic Minorities, especially Africans, Undermines City’s Claim to be Truly International. South China Morning Post. 21.

- Sorensen K, Broucke SVD, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, et al. (2012) Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health.

- Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, Rickwood D (2005) Measuring Help Seeking Intentions: Properties of The General Help Seeking Questionnaire.

- Demes KA, Geeraert N (2014) Measures Matter: Scales for Adaptation, Cultural Distance, and Acculturation Orientation Revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 45: 91-109.

- Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, Kruse WVR, et al. (2006) Performance of an Abbreviated Version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among Three European Community-Dwelling Older Adult Populations. The Gerontologist. 46: 503-513.

- Arbuckle JL (2012) IBM SPSS Amos (Windows Version 21) Computer Program. IBM Corporation

- Yiu HC, Zang Y, Chau JPC (2020) Barriers and Facilitators in the Use of Formal Dementia Care for Dementia Sufferers: A Qualitative Study with Chinese Family Caregivers in Hong Kong. Geriatric Nursing. 41: 885-890.

- Mukadam N, Cooper C, Livingston G (2011) A Systematic Review of Ethnicity and Pathways to Care in Dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 26: 12-20.

- Roche M, Higgs P, Aworinde J, Cooper C (2021) A Review Of Qualitative Research of Perception and Experiences of Dementia among Adults from Black, African, and Caribbean Background: What and Whom Are We Researching? The Gerontologist. 61: E195-E208.

- Mkhonto F, Hanssen I (2018) When People with Dementia are Perceived as Witches. Consequences for Patients and Nurse Education in South Africa. Journal Of Clinical Nursing. 27: E169-E176.

- Au A, Shardlow SM, Teng Y, Tsien T, Chan C (2012) Coping Strategies and Social Support-Seeking Behaviour Among Chinese Caring for Older People with Dementia. Ageing & Society. 33: 1422-1441.

- Doherty KV, Nguyen H, Eccleston CEA, Tierney L, Mason RL, et al. (2020) Measuring Consumer Access, Appraisal and Application of Services and Information for Dementia (CAAASI-Dem): A Key Component of Dementia Literacy. BMC Geriatrics. 20: 1-10.

- Gorczynski P, Sims-Schouten W, Hill D, Wilson JC (2017) Examining Mental Health Literacy, Help Seeking Behaviours, and Mental Health Outcomes in UK University Students. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice. 12: 111-120.

- Lee E (2022) Perceptions of Caregiving for People Living with Dementia and Help‐Seeking Patterns among Prospective Korean Caregivers in Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community. 30: e4885-e4893.

- Lee SYD, Stucky BD, Lee JY, Rozier RG, Bender DE (2010) Short Assessment of Health Literacy—Spanish and English: A Comparable Test of Health Literacy for Spanish and English Speakers. Health Research and Educational Trust. 45:1105-1120.

- Lee SE, Lee HY, Diwan S (2010) What Do Korean American Immigrants Know about Alzheimer‘s Disease (AD)? The Impact of Acculturation and Exposure to The Disease on AD Knowledge. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 25: 66-73.

- Lindsey MA, Joe S, Nebbitt V (2010) Family Matters: The Role of Mental Health Stigma and Social Support on Depressive Symptoms and Subsequent Help Seeking among African American Boys. Journal Of Black Psychology. 36: 458-482.

- Markova V, Sandal GM, Pallesen S (2020) Immigration, Acculturation, and Preferred Help-Seeking Sources for Depression: Comparison of Five Ethnic Groups. BMC Health Services Research. 20: 1-11.

- Meyers LS, Gamst G, Guarino AJ (2016) Applied Multivariate Research: Design And Interpretation. Sage Publications.

- Nutbeam D, Mcgill B, Premkumar P (2017) Improving Health Literacy in Community Populations: A Review of Progress. Health Promotion International. 1-11.

- Odewale O (2017) Social Network and Health Seeking Behaviour of Men of West African Descent Walden University.

- Parial LLB, Amoah PA, Chan KCH, Lai DWL, Leung A (2022) Dementia Literacy of Racially Minoritised People in A Chinese Society: A Qualitative Study among South Asian Migrants in Hong Kong. Ethnicity and Health. 28: 1-24.

- Park SY, Lee H, Kang M (2018) Factors Affecting Health Literacy among Immigrants-Systematic Review. European Journal of Public Health. 28(Suppl_4), Cky214. 283.

- Pretorius C, Mccashin D, Coyle D (2022) Supporting Personal Preferences and Different Levels of Need in Online Help-Seeking: A Comparative Study of Help-Seeking Technologies for Mental Health. Human–Computer Interaction. 39: 1-22.

- Sagong H, Yoon JY (2021) Pathways among Frailty, Health Literacy, Acculturation, and Social Support of Middle-Aged and Older Korean Immigrants in the USA. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18: 1245.

- Thakkar JJ (2020). Applications of Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS 21, IBM SPSS. Structural Equation Modelling. (Pp. 35-89).

- Tuliao AP, Velasquez PA (2014) Revisiting the General Help Seeking Questionnaire: Adaptation, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Further Validation in A Filipino College Student Sample.

- World Health Organisation. (2021a) Global Status Report on The Public Health Response to Dementia.

- Wu CY, Stewart R, Huang HC, Prince M, Liu SI (2011) The Impact of Quality and Quantity of Social Support on Help-Seeking Behaviour Prior to Deliberate Self-Harm. General Hospital Psychiatry. 33: 37-44.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.