Determinants of Quiet Quitting and Turnover Intention among Nursing Staff: The Case of Five Hospitals in the 2nd Regional Health Authority of Greece

by Eleni Chrysopoulou1*, Daniela Grammatopoulou2, Alexandra Skitsou3, Georgios Charalambous4

1Frederick University, Cyprus, G.H. Asklepieio, Voulas, Greece

2Genomic Medicine, England

3Nursing Department NKUA, visiting Assistant Professor, School of Health Sciences- Frederick University, Cyprus

4Professor, School of Health Sciences - Frederick University, Cyprus

*Corresponding author: Eleni Chrysopoulou, Frederick University, Cyprus, G.H. Asklepieio, Voulas, Greece

Received Date: 29 September 2025

Accepted Date: 07 October, 2025

Published Date: 10 October, 2025

Citation: Chrysopoulou E, Grammatopoulou D, Skitsou A, Charalambous G (2025) Determinants of Quiet Quitting and Turnover Intention among Nursing Staff: The Case of Five Hospitals in the 2nd Regional Health Authority of Greece. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 8:1675. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-9501.101675

Abstract

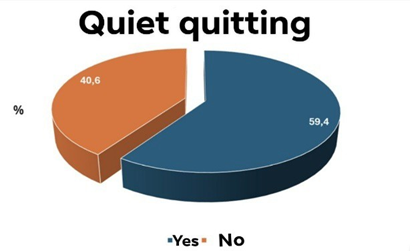

Objectives: The research examines factors that influence quiet quitting and turnover intention among nursing staff, focusing on work engagement and moral resilience. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study among nursing staff from January to March 2025 in Greece. We used the “QQS” to measure quiet quitting, a valid six-point Likert scale to measure turnover intention, the “RMRS16” to measure moral resilience, and the “UWES-9” to measure work engagement among nursing staff. We developed multivariable regression models adjusted for the socio-demographic characteristics of participants. Results: The study population included 1.012 nursing staff. The multivariable analysis identified a negative relationship between quiet quitting and turnover intention, with the determinants (moral resilience and work engagement). 59,4% of participants exhibited increased tendencies toward quiet quitting, and over 50% reported considering leaving their job with a frequency ranging from “sometimes” to “very often. Conclusions: Moral resilience and work engagement can be essential protective factors against quiet quitting and turnover intention among nursing staff.

Keywords: Quiet quitting; Turnover intention; Moral resilience; Work engagement; Nurses

Introduction

Nurses represent the largest and most critical professional group within healthcare organizations, as they spend the majority of their time providing direct patient care. Their contribution to service quality is undeniable, influencing healthcare efficiency, reducing medical errors, and ensuring positive patient outcomes [1]. Understanding the factors that affect nurses’ engagement, job satisfaction, and retention is therefore strategically important for the smooth operation and sustainability of healthcare systems.

Within this context, the phenomenon of quiet quitting has gained significant attention. It is not merely a behavioral choice but a complex psychological and organizational process. In healthcare, and particularly in nursing, quiet quitting is associated with chronic professional dissatisfaction, frustration, and psychological disengagement from work [2]. Manifestations include reduced professional initiative, lower empathy toward patients, decreased participation in interdisciplinary collaboration, and a general sense of detachment from professional growth [3]. Contributing factors, such as chronic understaffing, inadequate compensation, emotional exhaustion, and a lack of motivation, exacerbate the prevalence of this phenomenon.

Closely related to quiet quitting is turnover intention, defined as an employee’s conscious and deliberate intention to leave their current position within a specific timeframe [4]. In healthcare, turnover intention has critical implications, directly affecting organizational stability, service quality, and the sustainability of care systems. Nurses form the backbone of healthcare services, and their loss results in significant operational, social, and economic consequences [5,6].

Modern nursing roles are shaped by increasing ethical and professional challenges. Nurses face complex decisions that often extend beyond technical knowledge, including life-anddeath dilemmas, value conflicts, constraints in decision-making, and organizational pressures that may conflict with personal or professional ethics. Moral resilience has emerged as a key protective mechanism, enabling nurses to maintain professional integrity, mental well-being, and engagement. Defined by Rushton [7] as the capacity to sustain or restore moral integrity in the face of ethical challenges, moral resilience encompasses ethical competence, psychological strength, mindful reflection, and a commitment to core values such as justice, respect, empathy, and professional honesty [8].

Equally important is work engagement, a positive, motivational psychological state characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption in work [9]. High engagement levels are associated with psychological well-being, protection against burnout, increased professional responsibility, improved patient care, and reduced turnover intention [10-13]. Nurses who demonstrate strong engagement and moral resilience are better equipped to navigate the demands of modern clinical practice, ensuring both their personal well-being and the delivery of high-quality, safe healthcare.

Subjects and Methods

Study Participants

The study population included a total of 1,012 individuals, representing all levels of nursing staff (Registered and Technical Nurses, Assistant Nurses, Nursing Assistants, and Orderlies). Data were collected from five hospitals within the 2nd Regional Health Authority of Piraeus and the Aegean. Data were collected using an appropriate questionnaire from January 20 to April 20, 2025.

Statistical Methods

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 30.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences).

Categorical variables are presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies, while quantitative variables are summarized using mean, Standard Deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR), minimum, and maximum values. Normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and normality plots, with all dependent variables following a normal distribution.

Relationships between variables were examined using appropriate statistical tests: Student’s t-test for quantitative versus dichotomous variables, ANOVA for quantitative versus categorical variables with more than two groups, Spearman’s correlation for ordinal variables, and Pearson’s correlation for normally distributed quantitative variables. Variables with p<0.2 in bivariate analysis were included in multivariate linear regression using the backward stepwise method. Regression results are reported as beta coefficients (b), 95% confidence intervals, and p-values. The twotailed level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Dependent variables included scores on the three subscales of the quiet quitting questionnaire, the total quiet quitting score, and the overall turnover intention score.

Independent variables included scores on the four subscales of the moral resilience questionnaire, total moral resilience score, scores on the three subscales of the work engagement questionnaire, total work engagement score, and socio-demographic characteristics.

This analytical approach enabled a comprehensive examination of factors influencing quiet quitting and turnover intention among nursing staff, considering both moral resilience and work engagement as potential protective mechanisms.

Results

Demographic and work characteristics

The majority of participants were women (78.4%), with the largest age group being 41–50 years (39.4%). In terms of marital status, most were married (68.1%), and 71.1% reported having children. Regarding education, approximately one-third had completed secondary education (36.6%), while a similar proportion held a university or technical degree (35.9%). Employment status was predominantly permanent (81.1%), with 18.9% working under contract. The highest share of work experience fell within the 21– 30 years category (32.8%). In terms of income, over half earned €1,001–1,500 (56.3%). With respect to work departments, the majority were employed in ‘other departments’ (74.9%), though notable proportions worked in the ICU (11.3%) and Emergency Department (10.1%). Smaller shares were observed in Psychiatry (7.4%), the Emergency Department (7.0%), Outpatient Clinics (6.8%), and both the Operating Room and Surgical Department (4.5% each). Finally, the vast majority of participants (82.1%) reported working rotating shifts, while 17.9% did not.

Quiet Quitting

For the assessment of quiet quitting at work, the “Quiet Quitting Scale” (QQS) [14-16] was used. It consists of 9 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire comprises three subscales that address the following factors/dimensions: Detachment/ indifference, Lack of initiative, Lack of motivation.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was satisfactory (0.803).

|

Factor/Dimension |

Average |

SD |

M |

IQR |

Min |

Max |

|

Distancing/indifference |

1,94 |

0,74 |

1,75 |

0,75 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

|

Lack of initiative |

2,25 |

0,73 |

2,00 |

1,00 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

|

Lack of motivation |

2,82 |

0,90 |

3,00 |

1,50 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

|

Total quiet quitting score |

2,24 |

0,61 |

2,22 |

0,78 |

1,00 |

5,00 |

Table 1: Descriptive results for the overall quiet quitting score and its three dimensions.

Figure 1: Descriptive results for the overall quiet quitting score and its three dimensions (n = 1.012)

Turnover intention

The measurement of turnover intention was carried out with the question: “How often have you seriously considered leaving your job?” and was scored on a valid 6-point Likert scale, from 1 (never) to 6 (very often) [17].

|

Ν |

% |

|

|

How often have you seriously considered quitting your job? |

3,6 (1,6)a |

4,0 (2,8)b |

|

Never |

128 |

12,6 |

|

Rarely |

125 |

12,4 |

|

Sometimes |

246 |

24,3 |

|

Relatively often |

155 |

15,3 |

|

Quite often |

205 |

20,3 |

|

Very often |

153 |

15,1 |

|

a SD b IQR |

Table 2: Turnover intention (n = 1.012)

A significant proportion, nearly one in four (24.3%), reported that they consider leaving occasionally.

Moral Resilience

For the assessment of moral resilience, the Rushton Moral Resilience Scale-16 (RMRS) [18,19] was used, as it has been standardized in the Greek language. It consists of 16 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The questionnaire comprises four subscales that address the following factors/dimensions: Response to moral adversity, Personal integrity, Relational integrity, and Moral efficacy.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was acceptable (0.764).

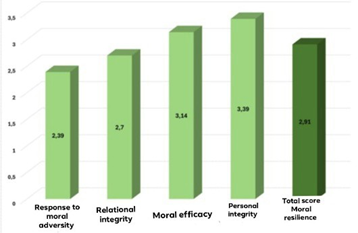

Figure 2: Mean scores for the dimensions of moral resilience and the overall moral resilience score. (n = 1.012).

Overall, personal integrity scored the highest (3.2–3.5), reflecting a strong sense of moral consistency. Response to moral adversity scored the lowest (2.2–2.7), indicating difficulty in managing the psychological effects of ethical dilemmas. Relational integrity showed moderate scores (2.2–3.4), suggesting some influence of interpersonal pressures, while moral efficacy was at a good level (3.0–3.3), demonstrating participants’ ability to understand and express their ethical positions.

Work Engagement

For the assessment of work engagement, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) [20,21] was used, as it has been standardized in the Greek language. It consists of 9 items rated on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always/every day). The questionnaire comprises three subscales addressing the following factors/dimensions: Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was excellent (0.927).

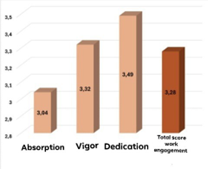

Figure 3: Mean scores for the dimensions of work engagement and the overall work engagement score. (n = 1.012)

The findings indicate that work engagement in the sample is expressed primarily through a sense of pride and dedication, and to a lesser extent through absorption in work.

Correlations between the dimensions of moral resilience and work engagement

The findings indicate that moral resilience is associated with work engagement, with stronger relationships observed between moral efficacy and the engagement dimensions, as well as between personal integrity and dedication. These results suggest that a sense of moral consistency and the ability to effectively apply ethical principles enhance vigor, dedication, and overall work engagement.|

Vigor |

Dedication |

Absorption |

Total score of work engagement |

||

|

Response to moral adversity |

Pearson |

0,151 |

0,157 |

0,077 |

0,139 |

|

p-value |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

0,014 |

<0,001 |

|

|

Personal integrity |

Pearson |

0,185 |

0,203 |

0,17 |

0,197 |

|

p-value |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

|

|

Relational integrity |

Pearson |

0,061 |

0,068 |

0,014 |

0,048 |

|

p-value |

0,054 |

0,030 |

0,654 |

0,126 |

|

|

Moral efficacy |

Pearson |

0,223 |

0,222 |

0,188 |

0,224 |

|

p-value |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

|

|

Total score of moral resilience |

Pearson |

0,238 |

0,25 |

0,17 |

0,233 |

|

p-value |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

<0,001 |

Table 3: Correlations between the dimensions of moral resilience and work engagement (including their subscales).

Dependent variable: Overall score of quiet quitting

According to the results of the multivariate linear regression, the following emerged: Men had higher overall scores of silent resignations from work compared to women (p = 0.028). An increase in years of work experience was associated with a decrease in overall silent resignation scores (p = 0.015). An increase in the overall moral resilience score was associated with a decrease in overall silent resignation scores (p < 0.001). An increase in the overall work engagement score was associated with a decrease in overall silent resignation scores (p < 0.001).

|

Independent variable |

b |

95% confidence interval |

p-value |

|

Gender |

-0,089 |

-0,169 to -0,010 |

0,028 |

|

Years of service |

-0,043 |

-0,077 to -0,008 |

0,015 |

|

Total score of moral resilience |

-0,459 |

-0,539 to -0,378 |

<0,001 |

|

Total score of work engagement |

-0,116 |

-0,140 to -0,092 |

<0,001 |

Table 4: Multivariate linear regression with the overall score of quiet quitting as the dependent variable.

Dependent variable: Turnover intention score

According to the results of the multivariate linear regression, the following emerged: Employees without children had higher turnover intention scores compared to those with children (p = 0.029). An increase in educational level was associated with a decrease in turnover intention scores (p = 0.023). Employees with rotating shifts had higher turnover intention scores compared to those not working in rotating shifts (p = 0.035). An increase in the overall moral resilience score was associated with a decrease in turnover intention scores (p = 0.001). An increase in the overall work engagement score was associated with a decrease in turnover intention scores (p < 0.001).

|

Independent variable |

b |

95% confidence interval |

p-value |

|

Existence of children |

0,230 |

-0,024 to -0,436 |

0,029 |

|

Educational level |

-0,126 |

-0,234 to -0,018 |

0,023 |

|

Working on rotating hours |

-0,267 |

-0,515 to -0,019 |

0,035 |

|

Total score of Moral resilience |

-0,390 |

-0,617 to -0,163 |

0,001 |

|

Total score of Work engagement |

-0,319 |

-0,386 to -0,251 |

<0,001 |

Table 5: Multivariate linear regression with Turnover intention as the dependent variable.

Discussion

The findings of the present study reinforce the growing concern reported in the international literature regarding the spread of quiet quitting among healthcare professionals, particularly nurses. The observation that male participants displayed higher levels of quiet quitting compared to women is consistent with the results of Moisoglou et al. (2020) [22], where greater disengagement was also recorded among men. This gender-based differentiation may reflect socio-cultural constructs regarding professional roles, as well as differences in how men and women express or internalize occupational dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the statistically significant association between years of work experience and lower levels of quiet quitting confirms the hypothesis that professional maturity and accumulated experience function as protective factors. This finding aligns with Galanis et al. (2023– 2024) [23,24], who observed a stronger intention to leave among younger and less experienced employees.

A particularly important aspect of the present study is the identification of moral resilience and work engagement as critical factors that reduce both quiet quitting and turnover intention. This finding is consistent with Antonsdottir et al. (2021) [25] and Rushton et al. (2022) [26], where moral resilience was highlighted as a protective mechanism against burnout and moral injury. The positive association found in this study between moral efficacy and the dimensions of work engagement (e.g., dedication, vigor) reinforces the role of moral resilience as a psychological resource that strengthens nurses’ ability to cope with ethical dilemmas and sustain professional identity and responsibility.

The results related to turnover intention showed that employees without children and those working rotating shifts were significantly more likely to consider leaving their jobs. This is in line with Alameddine et al. (2021) [27] and Edwards-Dandridge et al. (2020) [28], who reported high levels of turnover intention among professionals exposed to heavy workloads and low job satisfaction. The impact of rotating shifts may be attributed to disruptions in circadian rhythm, an imbalance between professional and personal life, and reduced social support often linked to irregular schedules. Conversely, the finding that having children is associated with lower turnover intention may reflect the increased need for stability and security that accompanies family responsibilities.

The present study also revealed that higher educational attainment is associated with lower turnover intention. This outcome differs from some earlier findings, which linked higher education to increased professional expectations and, consequently, a greater likelihood of dissatisfaction when these expectations are unmet (Cao & Chen, 2021) [29]. However, in certain professional contexts, higher education may provide nurses with greater autonomy, coping strategies, and a sense of control, thereby reducing their intention to leave.

In addition, the significant negative correlations observed between quiet quitting, moral resilience, and work engagement reinforce the conclusions of Poku et al. (2025) [30] and Nantsupawat et al. (2024) [31], who emphasized the protective effects of resilience and engagement against turnover intention and burnout. Our analysis indicates that nurses with greater moral consistency, capacity to manage moral adversity, and professional pride are less likely to disengage from their work or consider leaving their positions.

From a practical standpoint, the findings of this study highlight the need to develop and implement interventions that enhance nurses’ moral resilience and work engagement. Strategies such as support programs, ethics training, and professional development initiatives could play a significant role in reducing both quiet quitting and turnover intention. Furthermore, revising shift policies, improving staffing levels, and fostering supportive work environments are crucial measures to retain nursing staff.

Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. The sample was drawn from specific departments and hospital settings, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the use of self-reported questionnaires may have influenced the results due to socially desirable responses. Future research would benefit from incorporating qualitative data to capture the lived experience of quiet quitting in greater depth, as well as from longitudinal designs to examine the evolution of moral resilience and work engagement over time.

Conclusion

The present study provides valuable insights into the phenomenon of quiet quitting among nurses, highlighting its multifactorial nature and its close association with moral resilience and work engagement. The findings demonstrate that gender, years of professional experience, parental status, educational attainment, and work schedules are important determinants of both disengagement and turnover intention. In particular, rotating shifts and the absence of family responsibilities emerged as risk factors, whereas professional maturity and higher educational levels appeared to act as protective elements.

Crucially, the study confirmed the central role of moral resilience and work engagement as powerful buffers against quiet quitting and turnover intention. Nurses who maintain a strong sense of moral integrity, demonstrate efficacy in addressing ethical dilemmas, and cultivate dedication to their work are less likely to withdraw emotionally or consider leaving the profession. These results reinforce the need for healthcare organizations to invest in programs that strengthen ethical resilience, provide supportive environments, and foster professional pride.

From a practical perspective, targeted interventions such as ethics education, peer support initiatives, mentoring programs, and structural improvements in shift scheduling could significantly reduce disengagement and enhance retention. Such measures would not only safeguard the well-being of nursing staff but also ensure continuity and quality of care within healthcare systems already challenged by workforce shortages.

Although the study’s cross-sectional design and reliance on selfreported data limit the generalizability of the results, its findings open important avenues for future research. Longitudinal and qualitative approaches would allow for a deeper understanding of how quiet quitting evolves and how moral resilience can be cultivated in dynamic and complex healthcare environments.

In conclusion, addressing quiet quitting in nursing requires a dual focus: strengthening individual capacities for moral resilience and engagement, while simultaneously creating organizational conditions that support professional stability and fulfillment. By adopting this integrated approach, healthcare systems can mitigate the risks of disengagement and turnover, ultimately promoting a more resilient and committed nursing workforce.

Author Contribution Statement

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval Statement

The protocol for this research project has been approved by a suitably constituted Ethics Committee of the Institution and the Hospitals, and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Hospitals (Thriasio-General Hospital of Elefsina, Tzaneio General Hospital of Piraeus, Psychiatric Hospital of Attica, General Cancer Hospital of Piraeus “Metaxa”, and General Hospital of Nikaia, Piraeus “Agios Panteleimon”).

Data Availability Statement

Data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Al-Hamdan Z, Bani Issa H (2022) The role of organizational support and self-efficacy on work engagement among registered nurses in Jordan: A descriptive study. Journal of Nursing Management. 30: 2154-2164.

- Lee MA, Ju YH, Lim SH (2020) A study on the intent to leave and stay among hospital nurses in Korea: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Nursing Management. 28: 332-341.

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D (2021) Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 77: 3286-3302.

- Mobley WH, Griffeth RW, Hand HH, Meglino BM (1979) Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin. 86: 493-522.

- See ECW, Koh SSL, Baladram S, Shorey S (2023) Role transition of newly graduated nurses from nursing students to registered nurses: A qualitative systematic review. Nurse Education Today. 121: 105702.

- Zhong BL, Yuan MD, Li F, Sun P (2023) The Psychological Network of Loneliness Symptoms Among Chinese Residents During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16: 3767-3776.

- Rushton CH (2016) Moral Resilience: A Capacity for Navigating Moral Distress in Critical Care. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 27: 111-119.

- Young PD, Rushton CH (2017) A concept analysis of moral resilience. Nursing Outlook. 65: 579-587.

- Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-romá V, Bakker AB (2002) The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two-Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. Journal of Happiness Studies. 3: 71-92.

- Maslach C, Leiter MP (2016) Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 15: 103-111.

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2008) Towards a model of work engagement. The Career Development International. 13: 209-223.

- Hakanen JJ, Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB (2006) Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology. 43: 495513.

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, et al. (2015) Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90: 1600-1613.

- Galanis P, Katsiroumpa A, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, et al. (2023) The quiet quitting scale: Development and initial validation. AIMS Public Health. 10: 828-848.

- Petros Galanis, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, Irene Vraka et al. (2023) Quiet quitting among employees: a proposed cut-off score for the “Quiet Quitting” Scale. PREPRINT (Version 1).

- Petros Galanis, Aglaia Katsiroumpa, Irene Vraka et al. Nurses quietly quit their job more often than other healthcare workers: an alarming issue for healthcare services, 26 June 2023, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square.

- Spector PE, Dwyer DJ, Jex SM (1988) Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of Applied Psychology. 73: 11-19.

- Rushton CH, Hanson GC, Boyce D, Holtz H, Nelson KE, et al. (2024) Reliability and validity of the revised Rushton Moral Resilience Scale for healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 80: 1177-1187.

- Katsiroumpa A, Moisoglou I, Konstantakopoulou O, Tapaskou T, Gallos P, et al. (2023) Translation and validation of the revised “Rushton Moral Resilience Scale” in Greek.

- Ioannis Moisoglou RN, Aglaia Katsiroumpa RN, Antigoni Kolisiati MD (2025) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (nine items version): Translation and validation in Greek. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 18: 81-88.

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Salanova M (2006) The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 66: 701-716.

- Moisoglou I, Yfantis A, Galanis P, Pispirigou A, Chatzimargaritis E, et al. (2020) Nurses’ Work Environment and Patients’ Quality of Care.

- Galanis P, Katsiroumpa A, Vraka I, Siskou O, Konstantakopoulou O, et al. (2023) The influence of job burnout on quiet quitting among nurses: The mediating effect of job satisfaction.

- Galanis P, Moisoglou I, Malliarou M, Papathanasiou IV, Katsiroumpa A, et al. (2024) Quiet Quitting among Nurses Increases Their Turnover Intention: Evidence from Greece in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare. 12.

- Antonsdottir I, Rushton CH, Nelson KE, Heinze KE, Swoboda SM, et al. (2022) Burnout and moral resilience in interdisciplinary healthcare professionals. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 31: 196-208.

- Rushton CH, Nelson KE, Antonsdottir I, Hanson GC, Boyce D (2022) Perceived organizational effectiveness, moral injury, and moral resilience among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Management. 53: 12-22.

- Alameddine M, Clinton M, Bou-Karroum K, Richa N, Doumit MAA (2021) Factors Associated with the Resilience of Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 18: 320-331.

- Edwards-Dandridge Y, Simmons BD, Campbell DG (2020) Predictor of Turnover Intention of Registered Nurses: Job Satisfaction or Work Engagement? International Journal of Applied Management and Technology. 19.

- Cao X, Chen L (2021) Relationships between resilience, empathy, compassion fatigue, work engagement and turnover intention in haemodialysis nurses: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management. 29: 1054-1063.

- Poku CA, Bayuo J, Agyare VA, Sarkodie NK, Bam V (2025) Work engagement, resilience, and turnover intentions among nurses: A mediation analysis. BMC Health Services Research. 25: 71.

- Nantsupawat A, Kutney-Lee A, Abhicharttibutra K, Wichaikhum OA, Poghosyan L (2024). Exploring the relationships between resilience, burnout, work engagement, and intention to leave among nurses in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing. 23: 290.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.