Aggression Against Health Care Professionals, a Systematic Review

by Tom De Keyser1,2*, Paul Boon2,1

1Division of Head, Movement & Senses, Ghent University Hospital, Belgium

24Brain Research Group, Ghent University, Belgium

*Corresponding author: Tom De Keyser, Division of Head, Movement & Senses, Ghent University Hospital, Belgium

Received Date: 28 November, 2024

Accepted Date: 09 December, 2024

Published Date: 13 December, 2024

Citation: De Keyser T and Boon P (2024) Aggression Against Health Care Professionals, a Systematic Review. Int J Nurs Health Care Res 7:1607. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-9501.101607

Abstract

Introduction: Aggression against Health Care Professionals (HCP) is a common occurrence both in psychiatric or non-psychiatric inpatient and outpatient settings. The overall prevalence of patient perpetrated violence (workplace violence - type 2 (WPV2)) ranges from 9.5 to 74.6%, depending on the studied population, with verbal abuse as the most commonly reported form. Aim: A retrospective analysis of the literature for the last 13 years for workplace violence and aggressive behaviour against HCP, nurses in particular, including identification of evidence-based interventions to manage and prevent workplace violence or aggressive behaviour against HCP. Materials and methods: 6283 studies were identified by searching online databases (PubMed, Cochrane and CINAHL) using a variety of keyword combinations (aggression, workplace violence, health care professional, nurse, management and intervention). After screening on methodology (systematic reviews, meta-analysis, RCT) and screening in- and exclusion criteria 31 studies were eligible. 21 studies were finally included for this review after reading full text and verifying the specific aim of this review. 11 studies were descriptive, 10 had an interventional focus. Results: HCP are at high risk for experiencing violence. To be confronted with violence leads to serious emotional consequences such as depression (28.1%), anxiety, fear or helplessness (17.4% to 50.3%), reduced job satisfaction (69.2%) and lower work performance (30.1% to 31.1%).Overall, the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions was weak. The number of aggressive incidents (relative risk reduction -68%) and the number of patients engaged in aggression (relative risk reduction -50%) were significantly lower in groups systematically screened by risk assessment. Conclusion: WPV towards HCP is a frequent occurrence and has serious professional and personal consequences for HCP. Further research on the development of (more) effective interventions against aggression is highly needed.

Keywords: Workplace violence; Aggression; Health care professionals; Nurse; Management and Intervention

List of Abbreviations

WPV: Workplace Violence, HCW: Health Care Worker, SR: Systematic Review, MA: Meta-Analysis, ED: Emergency department, VA: Verbal aggression, PA: Physical Assault, MH: Mental Health, MHW: Mental Health Worker, CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Program, PVV: Patient and Visitor Violence, BO: Burn out, SIGN: Scottish intercollegiate guidelines network, ROBIS: Risk of bias in systematic review, RCT: Randomized Control Trial, GRADE: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation, GRADE-cerqual: GRADE-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research, EPOC: Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care group, RFC: Recovery Focused Care, CEP: Center for Evidence-Based Practice, AMSTAR: Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews, HCP: Health Care Professional

Introduction

Aggression against Health Care Professionals (HCP) is a common occurrence both in psychiatric or non-psychiatric inpatient and outpatient settings. In the previously published literature several definitions have been described. Odes et al. (2021) [1] describes violent events as physical or psychological acts perpetrated against an HCP by a patient, a visitor, an employee or a stranger. Simultaneously aggression at work is defined as Workplace Violence (WPV). WPV is any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation or other threatening disruptive behaviour that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide [2]. In this review, we will use the definition of the WHO, in particular WPV type 2: WPV by a customer or client. The perpetrator has a legitimate relationship with the business and becomes violent while being served by the business [2]. It is believed that a large portion of customer/ client incidents occur in the health care industry in settings such as nursing homes or psychiatric facilities; the victims are often caregivers.

Aggression Against Health Care Professionals, Nurses in Particular

Many studies related to WPV have observed that the risk of exposure to WPV type 2 is very high in the nursing and medical profession [3]. When nurses and physicians are compared in relation to exposure to WPV, the nursing profession faces the highest risk. This is due to the fact that they are most directly in contact with patients. There is a consensus in the international literature that nurses are the primary victim of WPV against HCP and at a higher risk of violence than any other type of healthcare staff [4,5]. This is because, compared with other healthcare professionals who only spent limited time with patients, nurses provide 24-hour and direct care for patients. They are exposed on the frontline to complicated situations that require a lot of control and that generate great emotional wear. They are therefore more likely to become the target of patient assault and offensive behaviour [6]. Various studies have shown that nurses, as a result of exposure to violence show the highest levels of burnout and emotional damage, translating into high levels of anxiety, lack of self-esteem, insomnia, depression or even physical distress [3].

The overall prevalence of patient perpetrated violence (WPV type 2) is highly variable. Numbers range from 9.5% to 74.6%, depending on the studied population, with verbal abuse being the most commonly reported form. Pompeii L, et al. (2020) and Liu J et al. (2019) [7,8] report that 61.9% of the participants were exposed to any form of WPV, 42.5% reported exposure to non-physical violence and 24.4% reported experiencing physical violence in the last year. Verbal abuse was also reported in this study as the most common form of non-physical violence (57.6%), followed by threats (33.2%) and sexual harassment (12.4%).

One of the most significant effects of WPV is a higher risk of burnout in exposed HCP. Giménez Lozano JM, et al. (2021) [3] concluded that there is a significant correlation between burnout symptoms and physical violence at work. On one hand, the risk factors that moderate this correlation were structural or organizational factors (social support, quality of the working environment and lack of autonomy) and personal factors (age, gender or academic degree). On the other hand, protective factors were the positive quality of the working environment and the presence of mutual support networks or coping strategies.

Focusing on individual factors, Giménez Lozano JM, et al. (2021) [3] showed that emotional demands, job satisfaction, and personal resilience had a direct influence on WPV. Consequences generated by violence at work are related to the high levels of stress experienced. A majority of studies have shown that HCP who have repeatedly been exposed to any type of WPV present high levels of anxiety, depression, generalized fear, insomnia or emotional problems that lead to more serious disorders such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or burnout.

Aims

The aim of this systematic review was twofold. Firstly, we intended to perform an analysis of the literature in the last 13 years (20112023) for WPV and aggressive behaviour against HCP, nurses in particular. Secondly, we identified evidence-based interventions to manage and prevent WPV or aggressive behaviour against HCP.

Materials and Methods Design

A systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) [9]. Databases were searched for relevant reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in English from January 2011 up to August 2023.

Search Methods

A search was carried out in August 2023 using the databases PubMed, Cochrane and CINAHL, searching for the following keywords: ‘Aggressive Behaviour’, ‘Workplace Violence’, ‘Health Care Professional’, ‘Nurse’, ‘Management’ and ‘Intervention’ or a combination of this terms.

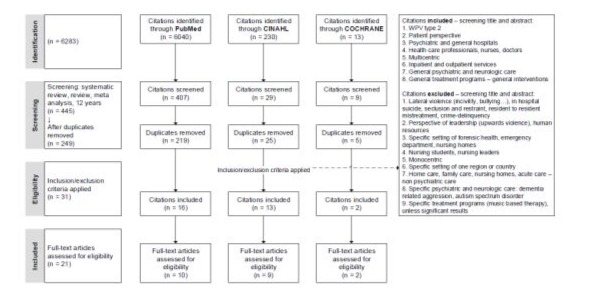

A first screening identified 6283 papers. In a second step, these manuscripts were screened on methodological requirements. Additionally, we screened on systematic reviews, reviews and meta-analyses from the last 13 years (January 2011- August 2023). This identified 445 single papers and after removing duplicates, still 249 were listed.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

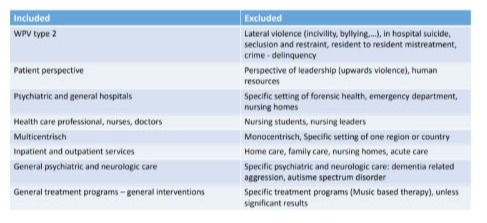

In a third step we applied additional inclusion and exclusion criteria as described in Table 1.

Table 1: Search strategy-in-and exclusion criteria for screening papers.

Search Outcome

After application of these additional criteria, 31 papers remained eligible. In a final step of the selection process, we studied these full text articles for congruency with the objectives of the current review and finally included 21 papers: 11 of them were descriptive, 10 had an interventional focus (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of paper screening and inclusion.

Quality Appraisal

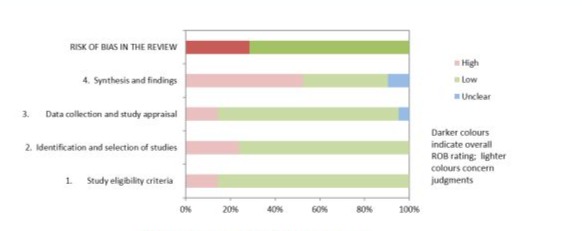

All of the included studies were systematic or scoping reviews, umbrella reviews, meta-analysis or a combination of these methods. The risk of bias of all studies was assessed using a tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews (ROBIS) [10]. Each paper was screened on four items and overall risk of bias was determined. Six papers showed a high risk of bias, 15 papers had a low risk. There was consensus of both authors for each paper. Results of this screening were presented in Table 2 (overall screening) and Table 3 (screening for each review).

Table 2: Overall ROBIS Screening.

|

Review |

Phase 2 |

Phase 3 |

||||

|

1. Study eligibility criteria |

2. Identification and selection of studies |

3. Data collection and study appraisal |

4. Synthesis and findings |

RISK OF BIAS IN THE REVIEW |

||

|

Pompei ea - 2020 |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

|

Dack ea - 2013 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Edward ea - 2014 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Edward ea - 2016 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Folgo ea - 2020 |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|

|

Odes ea - 2021 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

|

|

Zhang ea - 2021 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

|

Giménez Lozano ea- 2021 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Al-Qadi ea - 2021 |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|

|

Spencer ea - 2023 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

|

|

Rossi ea - 2023 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Tölli ea - 2017 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Raveel ea - 2019 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Martinez ea - 2016 |

High |

Low |

High |

High |

High |

|

|

Price ea - 2015 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Heckemann - 2015 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Lim ea - 2017 |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

High |

|

|

Geoffrion ea - 2020 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Spelten ea - 2020 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Kumari ea - 2022 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Fricke ea - 2023 |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Table 3: ROBIS Screening for Each Review.

Results-Descriptive Findings

This review only reports on patient-related violence (WPV type 2) and focuses on the frequency of aggressive acts, patient and HCP characteristics, risk and protective factors, the consequences of being confronted with patient aggression, the personal experience of HCP and the need of support.

Frequency

Overall Data

Overall data from an inpatient US-based psychiatric hospital indicate that assaults occur at a rate of between 2 and 7 assaults per 100.000 employee hours per year [1]. Between 25% to 85% of HCP had experienced an incident of violence during the past year. This research provides support for the widespread belief that such incidents happen frequently and rates are high in a range of treatment settings from small private units to large forensic facilities. A large survey of HCP working in mental health treatment wards in the UK showed that 78% of nursing staff had experienced aggression or threats at work. An additional study found that 76% of psychiatric nursing staff had experienced at least mild physical violence and 22% had taken days off work due to WPV during the last year. The systematic review of Liu et al. (2019) [8] demonstrates that the prevalence of WPV against HCP is high, especially in psychiatric and emergency departments and among nurses and physicians.

Verbal Abuse Versus Physical Abuse

Verbal abuse is the most frequently encountered experience of aggression in any setting. Nurses were more exposed to verbal aggression than physicians. The rates of verbal abuse reported by nurses ranged from 17% to 94% [11]. Violent episodes and physical assaults were identified as more prevalent in mental health settings than in general clinical environments. Working under time pressure, feelings of burnout in the caring role and young age all increased the risk for physical assault. Physical violence was more likely with patients with a history of alcohol use or having an acute intoxication and in case of miscommunication between nurses and patients [11]. Giménez Lozano JM, et al. (2021) [3] reported that in 90.2 % of the incidents the causal agent was the patient (N= 72, 65 were patients) and all of the participants (100%) reported verbal abuse, 79.1% just physical abuse. Liu J, et al. (2019) [8] reported that 61.9% of HCP were confronted to any form of WPV, 42.5% reported exposure to non-physical violence and 24.4% reported experiencing physical violence in the past year. Verbal abuse was the most common form of non-physical violence (57.6%), followed by threats (33.2%) and sexual harassment (12.4%).

Particular Setting of Nurses

The higher incidence of violence or aggression towards nurses when compared with physicians may be attributed to a number of factors: the length of time spent with the patient, perceived senior authority of physicians by patients, differences in communication style between nurses and physicians and miscommunication and misinformation [11].

Patient Characteristics

A meta-analysis [12] of 34 studies in an inpatient setting showed significant results by comparison of aggressive versus non aggressive groups for age (the younger the more aggressive), gender (males have a higher probability of being in the aggressive group), marital status (married patients are more likely to be in the non-aggressive group), psychopathology (a higher level of prevalence of schizophrenia in the aggressive group), type of admission (significantly higher numbers of aggressive patients were reported among those admitted involuntarily), number of previous admissions (aggressive patients had significantly more previous admissions), history of violence (aggressive patients were significantly more likely to have a history of previous violence), self-destructive behaviour (patients with a history of self-destructive behaviour were more likely to be in the aggressive group), and a history of substance abuse (patients with a history of substance abuse were more likely to be in the aggressive group).

Worker Characteristics

Edward et al. (2014) [11] reported that younger and less experienced nurses were more at risk of being exposed to violence in the workplace when compared with older and more experienced nurses. At the same time, male nurses were more likely to encounter physical assaults (which was more explicit in a mental health setting). This was confirmed by Edward et al. (2016) [13]. In 7 (of 10) studies male HCP were reported to suffer higher proportions of physical assault than female HCP. In this meta-analysis, the synthesized estimate for the difference in reported rates of physical assault between male and female staff indicated evidence for a significantly higher proportion of male staff experiencing physical assaults than female staff.

With regard to night and weekend work, nurses were more at risk of violence during night and weekend shifts [11]. This was attributed to the relative isolation in which these nurses work and lower staffing levels during these times. Finally, a history of verbal or physical assault in the personal life of a HCP increased the likelihood of experiencing such acts in the workplace.

For physicians, Pompeii L, et al. (2020) [7] reported a range in WPV prevalence from 24.4% to 59.3%, for nurses 9.5% to 62.1% and for receptionists 15.1% to 68.4%. With regard to years of work experience, the findings were mixed; some papers reported a direct relationship between those who had fewer years of work experience and the occurrence of WPV. Other papers reported opposite findings.

Edward et al. (2016) [13] described differences in physical assaults between non-mental health and mental health nurses in a metaanalytical study. The synthesized estimate for the difference in reported rates of physical abuse between mental health nurses and non-mental health nurses indicated evidence for a significantly higher proportion of mental health nurses experiencing physical assaults than non-mental health nurses. Psychiatric nurses have about three times the odds of experiencing physical assault from patients/relatives or staff than nurses in non-psychiatric settings. This difference was statistically significant and was based on a total sample size of over 900. Rossi et al. (2023) [14] confirmed these findings and found that the overall prevalence of WPV among HCP was reported to be as high as 78.9% and that nurses working in psychiatric wards were the professionals that were most impacted.

Risk and Protective Factors

In this review, numerous risk and protective factors appear to be strong determinants for WPV. Giménez Lozano JM, et al. (2021) [3] accomplished a systematic review of risk and protective factors for WPV to physicians and nurses. Regarding risk and protective factors, any action contrary to a risk factor, or in the opposite direction, is understood as a protective factor. They classified risk and protective factors into two series of categories, the structural/ organizational type, and the personal type.

Their review showed in the vast majority of the studies that the most frequent causal agent for WPV against HCP is the patient (90.2%; N=65); to a lesser extent, family members or partners (36.1%; N=26); and finally, co-workers (15.2%; N=11).

This was confirmed in the study of Odes et al. (2021) [1]. Researchers found that HCP who spend the most time providing direct care to patients in an inpatient psychiatric setting are most likely to experience WPV.

Logically, this is related to the type of contract HCP have, full-time (66.6%, N = 48) versus part-time (52%, N = 36). Giménez Lozano JM, et al. (2021) [3] indicated the higher the employment rate, the higher the exposure to aggression. In an outpatient setting. Pompeii L, et al. (2020) [7] found that if the perpetrator was a patient, there was a prevalence of 76.8% to 71.5%, if it was a companion or a relative from the patient prevalence ranged from 20.3% to 28.1%.

In addition, contextual factors for WPV were described in this review. On the level of patient care, misunderstanding between HCP and patients, unmet service needs and communication barriers increased the risk of WPV. The same effect was described on clinical factors; overcrowding of the clinic and long waiting times lead to high percentages of aggression incidents.

As normal, also security factors have their impact: lack of security, lack of protective measures and lack of penalty for the perpetrator when they were violent, had negative consequences on aggression rates.

Finally, additional determining factors were situated on the patient’s level. A lack of knowledge about their own health condition, being mentally ill, use of drugs, failure to receive a request for work leave or a sick note were factors that could lead to WPV.

Consequences

The most commonly reported consequences of WPV are burnout, emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and Loss of Personal Accomplishment (LPA) [3]. Women in the health care sector appear to suffer from higher burnout levels than men, women seem to have higher levels of EE and DP compared to men. The LPA subcategory is the only variable in which men have a higher risk than women. Nurses display higher levels of EE and LPA and have a higher risk of burnout compared to physicians.

Pompeii et al. (2020) [7] described the consequences of being exposed to WPV for HCP in an outpatient setting. Anxiety, fear or helplessness were commonly reported (17.4% to 50.3%), as well as reduced job satisfaction (69.2%), reduced work performance (30.1% to 31.1%), feeling depressed (28.1%) or angry (69.2%). In the most serious cases, HCP needed psychological support (3.0% to 5.8%). In the same systematic review, coping strategies for workplace violent events were described. Almost half of the victims (40.7%) indicated that they pretended as if the violent event did not happen. It was common for victims to report they did not take part in any form of coping mechanism (32.1% to 48.0%) or they coped by themselves (53.3%), while only a small proportion took time off (5.3% to 7.0%) or sought counselling (3.0%).

Personal Experience

Zhang et al. (2021) [6] identified four themes regarding the personal experience of nurses confronted with WPV. Firstly, many nurses experienced an inevitable and unpredictable trauma in their career. Nearly all participants expressed fear and they were particularly concerned about being attacked again. This experience left nurses frustrated and feeling powerless. All participants considered the verbal violence they encountered as routine and some of them regarded it as a natural daily occurrence rather than actual violence.

Secondly, a higher tolerance and understanding of unintentional violence was reported. If the acts of violence could be attributed to some underlying illness of their patients, nurses showed a higher level of tolerance and understanding. Unintentional violence was often viewed less negatively and closely related to resistance to care.

Thirdly, a positive relearning or passive adjustment coping strategy was displayed by many. Positive relearning is a coping strategy that reflects or refocuses on the event and adjusts the way nurses interact with the patient as a new learning experience. In this process, skills are relearned and good practices and expertise are reinforced. A small number of participants even reported that patient violence provided them with beneficial experiences and increased their confidence in their ability to intervene to prevent or manage patient violence. Passive adjustment is the use of alcohol or cigarettes as a coping strategy. Nurses had a drink or a cigarette at the end of the day or a chat during the break, which made it easier to endure these negative experiences.

Finally, Zhang et al. (2021) [6] described a struggle with their role and behaviour conflict after a violent incident. Nurses have to continue to care for and connect with violent patients, although they have not yet fully recovered from the psychological trauma after a violent incident. Sometimes, participants comforted themselves by rationalizing the violent behaviour of the patient in order to be able to continue caring for the perpetrators as usual, without any negative feelings or attitudes.

In the other case, patient violence affected the ability of nurses to perform professional nursing duties: although necessary care demands were met, nurses indicated that they lacked empathy for violent patients and they changed their attitudes towards the abuser. The interaction of some nurses with patients resulted in a less patient-centered and a more task-oriented relationship, which may represent a self-protective strategy for nurses.

These results were confirmed by Edward et al. (2014) [11]. In this review nurses reported sadness, shock, confusion, anger and embarrassment following an aggressive incident. The long-term effects of experiencing WPV were loss of confidence, absence from work, loss of good working relationships with colleagues and avoidance of the workplace, self-medication (including drugs and alcohol) and leaving the organization or even the profession.

Support Need

Two key themes concerning the support needs of nurses were identified. Zhang J, et al. (2021) [6] distinguished two different forms of support: informal and formal support needs.

Informal support needs were described as moments of informal contact such as interactions of encouragement with family and friends. In addition, colleagues play an important role from whom nurses expect empathic understanding. A supportive team can significantly mitigate the negative impact of abuse because this empathetic understanding of colleagues can provide immediate emotional support. A last informal factor was cooperation with their medical team. Nurses believed that physicians and nurses should cooperate under the same framework in dealing with aggressive patients. If physicians treat patients differently from nurses, patients may believe that physicians are ‘good’ and the nurses are ‘teasing’ them, prompting patients to target the nurses with violence.

Formal support needs were associated with the expectation of support from managers and legislation. Nurses need personal support and emotional input from managers after any violent incident. A lack of personal emotional support makes nurses feel uncomfortable and an open and blame-free context is significant in making nurses feel comfortable about reporting violence. Nurses need managers to be concerned about them from the perspective of being a victim, rather than the adverse impact of events on hospitals.

Finally, Zhang et al. (2021) [6] underlined the importance of postincident actions such as debriefing and reporting. Reporting was found to be the most common management strategy. Inefficient reporting methods could lead to adverse reactions such as distrust of management, damage to reputation or even punishment.

Results - Interventions

In this part, we focus on the effectiveness of different interventions to manage WPV.

Based on the results of all available studies, interventions can be clustered in four groups:

- The pre-event interventions such as violence prevention programs, risk assessment and risk control measures.

- The during-event interventions such as de-escalation techniques, a ‘code green’ response team or the ‘Safewards’ model.

- Post-event interventions, for example organizational support actions.

- Specific education and training programs having an effect on the pre-, the during- and the post-event phase.

Pre-Event Interventions

In a Cochrane review, Spelten E, et al. (2020) [15] focused on organizational interventions to prevent and minimize verbal or physical aggression against HCP and their peers in the workplace from patients or their relatives. Possible types of intervention focused on job design, incident reporting, procedures for raising an alarm or seeking assistance, organizational policies and procedures, physical restraint use and ensuring patients are kept informed. These interventions were categorized at three different levels; the level of the victim/HCP, the level of the perpetrator or their advocate and the level of social environment.

Combining these levels with the different types of intervention (pre-, per-, post-event) may lead to different comparisons.

- Patient-directed interventions at pre-event phase versus practice as usual. One study found that a short-term risk assessment decreased the number of incidents (risk ratio (RR) 0.36, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.78) with low-quality evidence.

- Patient directed interventions pre-event/during-event versus practice as usual. An intervention with the aim of changing culture by 7 different actions; a decreased number of physical aggressive events (MD 0.51, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.91) was described, with very low-quality evidence. There was no clear evidence for a decrease in verbal aggression (MD 0.76, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.54).

- Multicomponent intervention versus practice as usual. This intervention (multicomponent directed on the patient and the victim, and focused on the pre-event, event phase and the environment) did not result in a statistically significant effect on the occurrence of violent incidents.

Violence Prevention Programs

Martinez AJ (2016) and Lanza, et al. (2009) [16,17] described a ‘violence prevention community meeting’. The major intervention was a 30-minute meeting focused on violence prevention topics in psychiatric settings, which was conducted twice a week by nursing staff during the day shift and attended by patients. Topics of the community meeting led by nursing staff were (1) explaining unit rules, (2) stressing the importance of safety in the unit, (3) explaining what to do if losing control, (4) modelling problem solving, (5) discussing violence reduction measures, (6) discussing reactions regarding assaults and (7) discussing more acceptable alternatives to violence.

This study reported reduced incidents of violence by 85% among all shifts throughout the duration of the study and concluded that violence prevention community meetings are effective. This intervention was presented as a validated evidence-based intervention with promising results to manage WPV that can be implemented in inpatient psychiatric settings.

Risk Assessment and Risk Control Measures

As described in part one, there are many risk factors, which can provoke aggression. Measures of risk assessment and risk control may be meaningful. Raveel A, et al. (2019) [18] described the process of making risk assessment to develop risk control measures.

They categorized risk factors in five groups based on their origin: workplace design, work organization, patient factors, physician factors and social context. These authors also describe the following items as main risks for aggression: long waiting times, discrepancy between patient expectations and the services offered alcohol and drug abuse and psychiatric conditions. Subsequently, two types of risk control interventions were reviewed. First, changes to the physical environment such as effective indoor and outdoor lightening, sufficient exit routes, physical barriers, automatic door locks, video cameras, panic buttons, portable alarms and comfortable waiting areas. No evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions was found.

Secondly, changes in work policies were examined, such as a zero tolerance policy, training of staff and the implementation of a risk assessment. A zero tolerance policy typically includes a restriction or withdrawing of access to general care after episodes of aggression. No evidence on the impact of this measure on violence reduction was found. There is currently limited evidence that training of staff had a positive impact on the occurrence of violence (see education and training programs). Risk assessment tools focusing on patient aggression have shown to be effective as a predictor for short-term violence. Raveel A, et al. (2019) [18] reported from a Swiss study that the use of a short-term risk assessment tool in 14 acute psychiatric wards showed a significant reduction of severe violent events and a significantly reduced need for coercive measures. The intervention consisted of structured risk assessment twice a day, followed by communication of risk scores and recommendation for actions tailored to the risk level.

During-Event Interventions

During an aggressive incident, almost all studies recommend the same basic principles: attention to own safety and self-defense of the HCP, activation of an emergency procedure and use of restrictive interventions for patient safety. In addition, four different types of interventions during an aggressive episode can be distinguished.

Firstly, the non-coercive use of medication. This item is not included in this review given its specificity.

Secondly, interventions of a crisis response team. Martinez AJ (2016) [16] described the introduction of a code green response team (CGRT). The major functions of the CGRT typically include using the least restrictive measures, such as verbal de-escalation skills and non-coercive use of medication to control violent or escalating situations.

The results demonstrated that 85% of code green calls resulted in successful resolution of the violent incidents using verbal deescalation skills and non-coercive medication and a decrease of the application of restraints by 11%. Also Fricke J, et al. (2023) [19] reported about the effectiveness of a response team. While interventions such as staff education, de-escalation training and multidisciplinary violence rapid response teams, may be more beneficial when they are part of a multimodal strategy and not adopted in isolation, in general, there is a clear lack of high-quality evidence to evaluate effectiveness of these interventions.

Thirdly, de-escalation techniques. These techniques are a highly recommended component of violence prevention and a first choice intervention. De-escalation is executed in a three-step approach: the patient is verbally engaged, a collaborative relationship is established and the patient is verbally de-escalated out of the agitated state. It takes the form of a verbal loop in which the HCP listens to the patient, finds a way to respond the patient’s position and then states what he wants the patient to do [18].

Lavelle et al. (2016) [20] described de-escalation as the use of verbal and non-verbal communication to reduce or eliminate aggression and violence during the escalation phase of an aggressive incident. De-escalation is a first-line intervention in aggression management in (acute) psychiatric settings and a less coercive alternative to traditional containment methods. From the 784 sequences involving de-escalation, 61% were successful (ending after de-escalation), 35% unsuccessful (the sequence continued with conflict and containment events after de-escalation attempts), 4% ended after repeated de-escalation.

Overall, when implemented, de-escalation was successful in ending the sequence of conflict or containment in the majority of cases. Successful attempts had fewer and less aggressive, precursor events, compared with unsuccessful events. De-escalation was most effective when implemented early in the sequence of conflict and containment events.

Price et al. (2015) [21] described learning and performance outcomes of mental health staff training in de-escalation techniques for the management of violence and aggression. The strongest impact of training was on de-escalation knowledge and participant confidence to manage aggressive behaviour. There was evidence that confidence alone may not be particular useful in terms of predicting improvements in actual behaviour when faced with aggression.

Overall, in the published literature, no strong conclusions about the impact of de-escalation training on assaults, injuries, containment and organizational outcomes could be drawn owing to the low quality of evidence and conflicting results. Raveel A, et al. (2019) [18] described it most sharply: de-escalation is a highly specialized intervention requiring specific skills and this might explain the limited effectiveness of the training program.

The fourth group of during-event interventions includes the implementation of the Safewards model.

The Safewards model facilitates the implementation of a 10-point intervention program to reduce the occurrence of conflicts and the use of containment. Conflicts are situations which must be managed by HCP when actions of patients threaten the safety. Containment is defined as actions by HCP to avert or minimize harm.

The interventions include actions such as standards of behaviour made well know and displayed in the nursing ward, requirements to say something good about each patient at nursing shift handover, scanning for the potential bad news a patient might receive and intervening promptly to talk it through, a regular patient meeting to bolster, formalize and intensify inter-patient support, a crate of distraction and sensory modulation tools to use with agitated patients or a display of positive messages about the ward from discharged patients.

Bowers et al. (2015) [22] described the implementation of this model in an acute psychiatric ward. They observed that when conflicts occurred, the Safewards intervention reduced the rate of conflict by 15.0% (95% CI 5.6 to 23.7%). Similarly, the number of events leading to containment was reduced by 26.4% (95% CI 9.9 to 34.3%).

Post-Event Interventions

Post-event interventions focus on the impact of violent incidents on the emotional wellbeing and somatic health of HCP.

Raveel et al. (2019) [18] warned against the experience of violence as being ‘a part of the job’. Individual and organizational factors can lead to trivialization of WPV or a culture of silence and under-reporting. They described two factors playing a role in this trivialization. Firstly, normalization of violent behaviour of patients and their relatives, viewing this behaviour as just being ‘part of the job’. Secondly, taboo by avoiding an open discussion out of fear of being stigmatized as incompetent.

Colleague and employer support, training on violence and zero tolerance policies may contribute to normalization of violence. At the same time, these interventions decrease the likelihood of taboo. Organizations should be aware of this paradox implicitly arisen by sending the message that violence is to be expected. Also Schat et al. (2003) [23] focused on this item. Their study was formally excluded from this review because of an expired publication date but their findings are still relevant. They hypothesized that two types of organizational support (instrumental and informational) would interact with three dimensions of WPV (physical violence, psychological aggression and vicarious violence) to predict fear of future WPV, emotional well-being, somatic health, job-related affect and job neglect.

Instrumental support is defined as involving instrumental behaviours that directly helps the person in need, which might include taking care of or helping people, the involvement of coworkers, supervisors or management.

Informational support involves providing a person with information that the person can use in coping with personal and environmental problems. This could be informal (talking to colleagues) or more formal (training). The key distinction between instrumental and informational support is that instrumental support involves providing direct help or assistance, whereas informational support is a more indirect source of support that involves providing people with resources they can use to help themselves.

Instrumental support was found to significantly moderate the negative effects of WPV on emotional wellbeing, somatic health, and job-related affect, but not on fear of future WPV or job neglect.

Informational support significantly moderated the effects of WPV on emotional wellbeing but not the other four criteria.

Education And Training Programs

Education and training programs exceed the aforementioned distribution of the pre-, during- and post-interventions because they have effects on each phase of a violent incident. Education is defined as “the process of imparting knowledge and understanding of organizational policies and procedures, legal responsibilities and risk assessment and control strategies, including in relation to specific techniques that may be employed in one’s work environment, to prevent and mitigate the likelihood and consequences of exposure to WPV”. Training is defined as “the process of education about, and rehearsal and simulation or in vivo practice of, cognitive and behavioral skills that may be implemented in one’s work to prevent and minimize the likelihood and consequences of exposure to WPV” (Geoffrion et al., 2020) [24].

Thus, HCP should acquire a combination of knowledge, attitudes and skills that aim to prevent aggression in several ways such as de-escalation techniques, effective communication, conflict management, self-defense and evasion methods (Geoffrion et al., 2020) [24].

All studies in the Cochrane review [24] provided education in combination with training, 4 studies evaluated online programs and 5 studies evaluated face-to-face programs. Online programs were indicated as short or long duration or were self-paced. Faceto-face programs were subdivided in short, long and extended duration programs. In terms of reduction of the number of episodes of aggression, this review showed no statistically significant effect of training and education programs on the number of episodes of aggression. With regard to the effect of personal knowledge this review reported mixed findings. On short-term follow-up, there was low-quality evidence suggesting that education and training interventions improved knowledge about aggression. For longterm follow-up, low-quality evidence suggests that education and training interventions did not improve knowledge about aggression.

For attitudes toward patient aggression this review reported very low-quality evidence that education/training interventions improved attitudes among HCP at short-term follow-up. Two CRCTs and 3 RCTs measured effects of education interventions on the attitudes of participants toward patient aggression in shortterm follow-up. Results of the meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant effect on attitudes favouring the education group (SMD 0.59, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.94).

Regarding skills related to WPV, short-term follow-up suggests very low-quality evidence for HCP who underwent education interventions. They did not show more empathy than those in the control group at follow-up. Short-term follow-up of the adverse personal outcomes shows very low-quality evidence for a positive effect of education and training interventions. This training did not help mitigate the adverse outcomes of patient aggression for HCP. Overall, the conclusion of this Cochrane review [24] casted doubts on the effects of education and training interventions of reduction of episodes of aggression, compared to no intervention.

In terms of secondary outcomes, education may result in increased personal knowledge about WPV at short-term follow-up but may not be effective at long-term follow-up. Education may improve attitudes among HCP but the evidence is weak. In addition, the evidence for positive effects on skills related to WPV or on adverse personal outcomes is thin.

In addition to the Cochrane review, Heckemann B, et al. (2015) [25] discussed the effects of training in an acute hospital setting. They described effects on four levels; effects of training on attitude, confidence, knowledge/skills and the incidence rate of aggressive incidents. There was no unambiguous evidence that training enhances the management of aggression and changes staff attitudes. The overall ratings of attitude of the participants were higher post-training but the majority of changes were not statistically significant. The overall effect of the training on confidence of HCP was positive, with significant increases in confidence reported in 3 studies. Feelings varied depending on the situation, yet overall, staff members reported feeling safer in their workplace after a training.

In two studies, the effect of training on knowledge and skills was confirmed by an increase in risk factor detection in short-term and even a further improvement at 3-month follow-up. Finally, the effect of training on incidence rate of aggression showed a significant decrease in verbal aggression and an initial decrease in physical aggression after the training. Overall, all of nine studies reported positive effects relating to one or more of 3 levels: individual attitude and confidence, incidence of aggression and individual competence. Seven out of the nine studies assessed either changes in confidence, attitude, or both, and concluded that the training had positively influenced staff members. These multiple sources indicate that training interventions truly have a positive effect on attitude and confidence regarding management of aggression.

In another systematic review, Tölli S, et al. (2017) [26] described four types of training interventions for managing aggressive behaviour. Disengagement skills, communication skills, controlling behaviour symptoms and restrictive measures. The effect on competences and evaluation measurement, were described in 3 elements: staff attitudes and perceptions of violence and what caused it, the confidence to cope with aggressive behaviour and the knowledge of good practice in managing aggressive behaviour.

They concluded that the most effective training interventions fell into the communication category and most of these had a significantly positive impact on confidence. Confidence increased significantly after training for both qualified and unqualified staff members. A significant increase was also detected in the subjects ability to cope with adverse working situations before and after the intervention.

The interventions in the disengagement category also showed statistically significant increases in confidence and safety levels. Weak evidence was found for two interventions in the communication group which showed reduced violent incident rates. For the use of restraint, one study reported in a 7-month follow-up that the use of restraint was significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the control group after a staff training. Overall, training interventions were more likely to increase staff confidence than change staff attitudes or increase their knowledge. However, generally the published evidence was mostly weak.

Discussion

The present review had a double purpose.

Firstly, we intended to perform an analysis of the literature in the last 13 years for WPV and aggressive behaviour against HCP, nurses in particular.

This review demonstrated that WPV has a high prevalence. Mental HCP, specifically nurses are regularly exposed to challenging and potentially hazardous situations, increasing their susceptibility to WPV [3,6] Several studies have consistently shown that mental HCP experience higher rates of verbal abuse [3,7,8,11], threats [8], physical assaults [11,13] and other forms of violence compared to HCP in other sectors. Reported aggression is often related to dynamic factors and is highly context-related [7].

Being confronted with violence leads to serious emotional consequences for HCP, including depressed feelings (28.1%), anxiety, fear, or helplessness (ranging from 17.4% to 50.3%) [3,7] Additionally, incidents of violence are associated with reduced job satisfaction (69.2%) and lower work performance (ranging from 30.1% to 31.1%) [3,7]. These statistics underscore the profound impact of WPV on the psychological well-being and professional satisfaction of mental HCP, highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions to mitigate this pervasive issue, protect HCP and ensure the continuity of quality care.

Secondly, we have identified evidence-based interventions to manage and prevent WPV or aggressive behaviour against HCP.

Training and education programs represent interventions for preventing and managing WPV in mental health care settings. Comprehensive training initiatives equip HCP with the necessary knowledge and skills to identify warning signs, de-escalate aggressive situations, and implement effective safety protocols. The evidence was rather weak; nevertheless, educational interventions foster a culture of awareness and accountability, empowering mental HCP to advocate for their safety and support colleagues in distress [24]. Investments in training and education result in improvements in personal knowledge, attitudes and confidence levels.

Risk assessment tools serve as valuable instruments for predicting and mitigating WPV in mental health care settings. By systematically evaluating individual and environmental risk factors, these tools enable HCP to proactively identify potential threats and implement targeted interventions [15,18].

Finally, the Safewards model offers a comprehensive framework for promoting safety and reducing conflict in mental health care settings. Grounded in principles of relational security, this model emphasizes collaboration, empowerment, and deescalation techniques to foster a therapeutic environment conducive to recovery. This review suggests that implementation of the Safewards model leads to significant reductions in WPV incidents, improvements in staff morale, and enhanced service user experiences [22]. By addressing underlying environmental stressors and enhancing staff-patient relationships, the Safewards model represents a promising approach to WPV prevention and intervention in mental health care settings [22].

Limitations of the Work

This systematic review was conducted from the perspective of psychiatric and neurological practice, which may have introduced biases or overlooked certain perspectives.

The review was restricted to articles published in English only, potentially excluding relevant research conducted in other languages, leading to the possibility of language bias and missing out valuable insights from non-English literature. The search was confined to only three databases without manual searches or other literature sources. This may have resulted in overlooking relevant studies that are not indexed in the selected databases, potentially leading to incomplete evidence synthesis.

The study limited the search to publications within a 13-year period, which may have excluded older but still relevant studies in the field of WPV, potentially compromising the comprehensiveness of the review. There is a methodological restriction. The systematic review focused only on reviews, systematic reviews (SR), and meta-analyses (MA), potentially omitting other types of studies that could provide valuable insights or perspectives relevant to the research question.

The majority of the research showed a weak evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions that were assessed.

Recommendations for Further Research

Considering the limitations of the methodology of published research and the low evidence for positive outcomes of existing interventions, further research with a more rigorous methodology and the development of (more) effective interventions against aggression is highly needed. This systematic review will be followed by analysis of a large prospectively collected data set at Ghent University Hospital during the past 5 years. The data will be analysed and benchmarked to the conclusions of this review. At a later stage an interventional study will be setup in which newly developed interventions will be designed and tested for effectiveness.

Implications for policy and practice of the currently available research

To effectively address WPV in mental health care settings, policymakers and stakeholders must prioritize the following actions:

- Implement comprehensive training and education programs that equip mental HCP with the necessary skills to prevent and manage WPV incidents.

- Incorporate evidence-based risk assessment tools into routine practice to identify and mitigate potential threats proactively.

- Promote the Safewards model as a holistic approach to WPV prevention, emphasizing collaboration, empowerment and relational security.

- Allocate sufficient resources and support for mental HCP or organizations to implement and sustain effective WPV interventions.

Conclusion

Health care professionals are at high risk for experiencing work place violence. The overall prevalence of WPV type 2 ranges from 9.5% to 74.6% depending on the studied population, with verbal abuse as the most commonly reported form. Reported aggression is related to dynamic factors which makes it unpredictable and highly context-related. A patient history of violence and psychiatric conditions, such as alcohol abuse and addiction, are risk factors which increase the probability of WPV. The higher incidence of WPV towards nurses when compared to physicians may be attributed to the length of time spent with the patient or differences in communication style between nurses and physicians.

To be confronted with violence leads to serious emotional consequences such as depressed feelings, anxiety, fear or helplessness, as well as reduced job satisfaction and lower work performance.

Because of the high prevalence of WPV and the impact on the HCP, it is important to rely on evidence-based interventions for the prevention of WPV and the protection of the HCP. However, the methodology of the included studies, investigating one or more interventions to manage aggression and the published evidence level, was overall weak. None of the studies reported interventions that are unequivocally and highly effective. A risk assessment seems to lead to a distinct reduction of aggression events. The number of aggression incidents and number of patients engaged in aggression were significantly lower in the groups systematically screened by a risk assessment. There is moderate evidence that an integrated violence prevention programme can decrease the risk of WPV. The use of de-escalation techniques during an event of aggression is highly recommended.

Implementing the interventions of the Safewards model could reduce both the rate of conflict and containment events. Considering the weak methodology of the published research and the low evidence level for positive outcome of existing interventions, further research with a more rigorous methodology and the development of (more) effective interventions against aggression is highly needed.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Ethical Guidelines

This research does not require ethical approval.

Conflict of interest

With regard to the content of this manuscript, Tom De Keyser and prof. dr. P. Boon report no potential conflict of interest. There is no patient or public contribution. Funding for open access publication was provided by 4Brain at Ghent University.

References

- Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, Ackerman S, Hong O (2021) Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States’ inpatient psychiatric hospitals: A systematic review of literature. International journal of mental health nursing. 30: 27-46.

- Richards, J (2003) Management of workplace violence victims.

- Giménez Lozano JM, Martínez Ramón JP, Morales Rodríguez FM (2021) Doctors and Nurses: A Systematic Review of the Risk and Protective Factors in Workplace Violence and Burnout. International journal of environmental research and public health. 18: 3280.

- Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, Luborsky M, Upfal MJ, et al. (2015) Underreporting of Workplace Violence: Comparison of Self-Report and Actual Documentation of Hospital Incidents. Workplace health & safety. 63: 200-210.

- Chapman R, Styles I, Perry L, Combs S (2010) Examining the characteristics of workplace violence in one non-tertiary hospital. Journal of clinical nursing. 19: 479-488.

- Zhang J, Zheng J, Cai Y, Zheng K, Liu X (2021) Nurses’ experiences and support needs following workplace violence: A qualitative systematic review. Journal of clinical nursing. 30: 28-43.

- Pompeii L, Benavides E, Pop O, Rojas Y, Emery R (2020) Workplace Violence in Outpatient Physician Clinics: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 17: 6587.

- Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, et al. (2019) Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and environmental medicine.76: 927-937.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 29: 372:n71.

- Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, et al. (2016) ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 69: 225-234.

- Edward KL, Ousey K, Warelow P, Lui S (2014) Nursing and aggression in the workplace: a systematic review. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 23: 653-659.

- Dack C, Ross J, Papadopoulos C, Stewart D, Bowers L (2013) A review and meta-analysis of the patient factors associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 127: 255-268.

- Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, Lui S, Warelow P, et al. (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. Journal of clinical nursing. 25: 289-299.

- Rossi MF, Beccia F, Cittadini F, Amantea C, Aulino G, et al. (2023) Workplace violence against healthcare workers: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Public health. 221: 50-59.

- Spelten E, Thomas B, O‘Meara PF, Maguire BJ, FitzGerald D, et al. (2020) Organisational interventions for preventing and minimising aggression directed towards healthcare workers by patients and patient advocates. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 4: CD012662.

- Martinez AJ (2016) Managing Workplace Violence With EvidenceBased Interventions: A Literature Review. Journal of psychosocial nursing and mental health services. 54: 31-36.

- Lanza ML, Rierdan J, Forester L, Zeiss RA (2009) Reducing violence against nurses: the violence prevention community meeting. Issues in mental health nursing. 30: 745-750.

- Raveel A, Schoenmakers B (2019) Interventions to prevent aggression against doctors: a systematic review. BMJ open. 9: e028465.

- Fricke J, Siddique SM, Douma C, Ladak A, Burchill CN, et al. (2023) Workplace Violence in Healthcare Settings: A Scoping Review of Guidelines and Systematic Reviews. Trauma violence abuse. 24: 3363-3383.

- Lavelle M, Stewart D, James K, Richardson M, Renwick L, et al. (2016) Predictors of effective de-escalation in acute inpatient psychiatric settings. Journal of clinical nursing. 25: 2180-2188.

- Price O, Baker J, Bee P, Lovell K (2015) Learning and performance outcomes of mental health staff training in de-escalation techniques for the management of violence and aggression. The British journal of psychiatry. 206: 447-455.

- Bowers L, James K, Quirk A, Simpson A, Hodsoll J (2015) Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: The Safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. International journal of nursing studies. 52:1412-1422.

- Schat AC, Kelloway EK (2003) Reducing the adverse consequences of workplace aggression and violence: the buffering effects of organizational support. Journal of occupational health psychology. 8: 110-122.

- Geoffrion S, Hills DJ, Ross HM, Pich J, Hill AT, et al. (2020) Education and training for preventing and minimizing workplace aggression directed toward healthcare workers. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD011860.

- Heckemann B, Zeller A, Hahn S, Dassen T, Schols JM, et al. (2015) The effect of aggression management training programmes for nursing staff and students working in an acute hospital setting. A narrative review of current literature. Nurse education today. 35: 212-219.

- Tölli S, Partanen P, Kontio R, Häggman-Laitila A (2017) A quantitative systematic review of the effects of training interventions on enhancing the competence of nursing staff in managing challenging patient behaviour. Journal of advanced nursing. 73: 2817-2831.

- Al-Qadi MM (2021) Workplace violence in nursing: A concept analysis. Journal of occupational health. 63: e12226.

- Anderson L, FitzGerald M, Luck L (2010) An integrative literature review of interventions to reduce violence against emergency department nurses. Journal of clinical nursing. 19: 2520-2530.

- Azami M, Moslemirad M, YektaKooshali MH, Rahmati S, Soleymani A, et al. (2018) Workplace Violence Against Iranian Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.Violence and victims. 33: 1148-1175.

- Caruso R, Toffanin T, Folesani F, Biancosino B, Romagnolo F, et al. (2022) Violence Against Physicians in the Workplace: Trends, Causes, Consequences, and Strategies for Intervention. Current psychiatry reports. 24: 911-924.

- Cornaggia CM, Beghi M, Pavone F, Barale F (2011) Aggression in psychiatry wards: a systematic review. Psychiatry research. 189: 1020.

- Flannery RB, Flannery GJ (2023) Characteristics of International Staff Victims of Psychiatric Patient Assaults: Review of Published Findings, 2017-2022. The Psychiatric quarterly. 94: 79-88.

- Folgo AR, Iennaco JD (2020) Staff perceptions of risk factors for violence and aggression in ambulatory care. Work (Reading, Mass.). 65: 435-445.

- Gaynes BN, Brown CL, Lux LJ, Brownley KA, Van Dorn RA, et al. (2017) Preventing and De-escalating Aggressive Behavior Among Adult Psychiatric Patients: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.). 68: 819-831.

- Higgins N, Meehan T, Dart N, Kilshaw M, Fawcett L (2018) Implementation of the Safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. International journal of nursing studies. 88: 114-120.

- Kumari A, Sarkar S, Ranjan P, Chopra S, Kaur T, et al. (2022) Interventions for workplace violence against health-care professionals: A systematic review. Work (Reading, Mass.). 73: 415-427.

- Kynoch K, Wu CJ, Chang AM (2011) Interventions for preventing and managing aggressive patients admitted to an acute hospital setting: a systematic review. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing. 8: 76-86.

- Lamont S, Brunero S (2018) The effect of a workplace violence training program for generalist nurses in the acute hospital setting: A quasiexperimental study. Nurse education today. 68: 45-52.

- Lim E, Wynaden D, Heslop K (2017) Recovery-focussed care: How it can be utilized to reduce aggression in the acute mental health setting. International journal of mental health nursing. 26: 445-460.

- Muir-Cochrane E, Oster C, Gerace A, Dawson S, Damarell R, et al. (2020) The effectiveness of chemical restraint in managing acute agitation and aggression: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. International journal of mental health nursing. 29: 110-126.

- Nikathil S, Olaussen A, Gocentas RA, Symons E, Mitra B (2017) Review article: Workplace violence in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta analysis. Emergency medicine Australasia : EMA. 29: 265-275.

- Pagnucci N, Ottonello G, Capponi D, Catania G, Zanini M, et al. (2022) Predictors of events of violence or aggression against nurses in the workplace: A scoping review. Journal of nursing management. 30: 1724-1749.

- Pompili E, Carlone C, Silvestrini C, Nicolò G (2017) Focus on aggressive behaviour in mental illness. Focus on aggressive behaviour in mental illness. Rivista di psichiatria. 52: 175-179.

- Ridenour M, Lanza M, Hendricks S, Hartley D, Rierdan J, et al. (2015) Incidence and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric staff. Work (Reading, Mass.). 51: 19-28.

- Spector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX (2014) Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. International journal of nursing studies. 51: 72-84.

- Spencer C, Sitarz J, Fouse J, DeSanto K (2023) Nurses‘ rationale for underreporting of patient and visitor perpetrated workplace violence: a systematic review. BMC nursing. 22: 134.

- Tuominen J, Tölli S, Häggman-Laitila A (2023) Violence by clients and patients against social and healthcare staff - An integrative review of staff‘s well-being at work, implementation of work and leaders‘ activities. Journal of clinical nursing. 32: 3173-3184.

- van de Sande R, Nijman HL, Noorthoorn EO, Wierdsma AI, Hellendoorn E, et al. (2011) Aggression and seclusion on acute psychiatric wards: effect of short-term risk assessment. The British journal of psychiatry.199: 473-478.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.