World-first Custom-made Facial Skeleton Replacement: Integrating Surgical Innovation, Engineering Optimization, and Biomechanical Precision

by Hendrik Koops1, Symon Guthua2, Margaret N. Mwasha3, Vincent Nevelsteen4, Joan Aluoch Melissa5, Michael Mwambi6, Maurice Y Mommaerts7*

1CADskills bv, 9051 Gent, Belgium

2Department of Dental Sciences, Unit of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine, University of Nairobi, Kenya

3Department of Dental Sciences, Division of Prosthodontics, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya 1CADskills bv, 9051 Gent, Belgium

5Engineering, Additive Tech on Anatomy Ltd P.O Box 97-00202, Nairobi, Kenya and University of Global Health Equity, P.O. Box 6955 Kigali, Rwanda

6Engineering. Additive Tech on Anatomy Ltd. P.O Box 97-00202, Nairobi, Kenya

7Face Ahead Surgicentre and ZAS Vincentius, Antwerp, Belgium

*Corresponding author: Maurice Y Mommaerts, Face Ahead Surgicentre and ZAS Vincentius, Antwerp, Belgium

Received Date: 08 December 2025

Accepted Date: 12 December 2025

Published Date: 15 December 2025

Citation: Koops H, Guthua S, Mwasha MN, Nevelsteen V, Melissa JA, et al. (2025) World-first Custom-made Facial Skeleton Replacement: Integrating Surgical Innovation, Engineering Optimization, and Biomechanical Precision. J Surg 10:11512 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011512

Abstract

Background: Polyostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the mandible, maxilla, and zygomatic complexes presents profound functional and reconstructive challenges. Conventional approaches fail to address the combined requirements of structural support, musculofascial reintegration, Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) biomechanics, and midfacial aesthetics. This report details the engineering, design, and implementation of a comprehensive, custom-made alloplastic reconstruction tailored to a young adult with extensive disease. Methods: A 28-year-old patient with widespread craniofacial involvement underwent virtual surgical planning using mirrored CTderived anatomical modeling. Titanium Grade 23 ELI and tocopherol-enriched highly cross-linked ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (AO-HXPE) were selected for their biomechanical compatibility and stability. The design incorporated a three-part facial implant system recreating the mandible, maxilla, zygomatic structures, orbital floor, and dentition. Engineering features included a lightweight mandibular scaffold, expanded enthesis surfaces, and a Condyle-in-a-Box TMJ mechanism enabling physiological rotational and translational movement. Surface treatments—polishing, sandblasting, and HadSat coating—were applied to enhance biological performance. Surgery proceeded with resection, removal of a prior orbital mesh, staged implant placement, and muscle reattachment.

Results: The final mandibular prosthesis achieved a mass reduction from 112 g to 69 g (112 g with dental prosthesis) through strategic perforation and scaffold optimization while maintaining structural integrity. Muscle reattachment zones were expanded, and implant geometry preserved airway access, nasolacrimal anatomy, and orbital support. The multicomponent design and engineered impactor indentations facilitated accurate intraoperative alignment, allowing successful reconstruction of form, occlusion, and function. Conclusion: This case demonstrates how interdisciplinary collaboration, computational engineering, and optimized biomaterials enable anatomically precise and functionally robust reconstruction of massive craniofacial defects. The methodology establishes a reproducible framework for future applications requiring integration of biomechanics, surgical workflow, and advanced implant manufacturing.

Keywords: Craniofacial Reconstruction; Fibrous Dysplasia of Bone; Patient-Specific Implants; Temporomandibular Joint; Titanium; Virtual Surgical Planning

Introduction

Fibrous Dysplasia (FD) is a benign fibro-osseous disorder characterized by replacement of normal bone with fibrous stroma and immature woven bone. Craniofacial involvement may cause facial asymmetry, visual compromise, feeding problems, and airway dysfunction. Clinical series emphasize that disease extent dictates treatment strategy, with conservative contouring reserved for stable lesions and radical resection considered for functional or aesthetic deterioration [1]. Recent advancements have improved the precision of craniofacial FD correction. Navigation-assisted osteotomies and mirroring-based virtual planning permit recontouring with greater accuracy and reduced risk near the skull base and orbit [2-4]. For extensive orbitocranial disease, radical resection with titanium reconstruction may restore symmetry and reduce recurrence risk [5]. Nevertheless, cases of FD invading pre-existing titanium mesh highlight the unpredictable biological behavior of recurrent disease [6]. Pharmacologic therapies, including bisphosphonates, may reduce pain but have limited impact on lesion progression [7]. Parallel innovations in patient-specific implant design have expanded reconstructive possibilities. Systematic reviews describe the evolution of alloplastic TMJ prostheses, highlighting biomaterial considerations, joint biomechanics, and surgical integration [8,9]. Additively Manufactured Sub-Periosteal Jaw Implants (AMSJI) represent a prosthesis-driven solution for severe maxillary atrophy and resection defects, avoiding bone grafts while restoring dental function [10]. Iterative refinements in framework geometry, surface treatment, and finite element modeling have improved osseous interaction and long-term stability [11]. Clinical studies on AMSJI demonstrate low bone resorption, high patient satisfaction, and predictable remodeling patterns in severely atrophic jaws [12-16]. Guidelines emphasize attention to flap design, soft-tissue management, and component segmentation to minimize recession and exposure [12,17]. The present case extends these principles beyond maxillary or TMJ-specific applications. It describes the reconstruction of a patient with extensive polyostotic FD requiring resection and replacement of the mandible, maxilla, zygoma, orbital floor, palate, and TMJ. A fully integrated, multi-component alloplastic reconstruction was engineered to restore both form and function-representing a rare application of combined TMJ, sub-periosteal, and midface implant technologies in a single craniofacial framework.

Materials and Methods

Preoperative Assessment

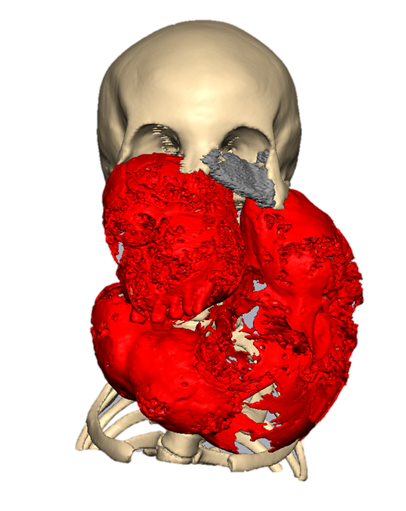

The patient presented with extensive polyostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the mandible, maxilla, and large portions of the zygomatic complexes (Figure 1). This condition, characterized by the replacement of normal bone with fibro-osseous tissue, leads to deformity, compromised functionality, and chronic pain, as documented in clinical studies [18]. The patient, estimated to be 28 years old and standing approximately 1.50 meters tall with a weight of 35 kg, had undergone a surgical intervention in 2015 during which a titanium mesh plate was placed in the left orbital floor. The planned reconstruction includes the removal of this preexisting mesh. Additionally, a tracheostomy was planned to ensure airway stability during the surgical procedure. The condition of the associated musculature remained unknown, complicating the surgical and rehabilitative approaches. The reconstruction aimed to restore essential functions compromised by the disease. Airway function must be restored, with the mandibular component designed to preserve access to the trachea. Restoring speech function requires the mobility of the mandible and associated structures to facilitate articulation. Jaw mobility is also critical for masticatory function, ensuring proper occlusion and chewing ability. Vision restoration involves reestablishing orbital support to provide binocular alignment and maintain ocular health.

Figure 1: Preoperative imaging showing extensive fibrous dysplasia of the mandible, maxilla, and bilateral zygomatic complexes (red), the pre-existing orbital mesh (grey) and the remaining healthy bone (beige).

Material Science Considerations

The reconstruction demands materials and designs that meet several critical functional criteria. Biocompatibility is paramount, ensuring that the materials do not elicit an inflammatory or foreign body response. Therefore, titanium Gr23 ELI and UltraHigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) enriched with tocopherol were chosen. These materials are well-documented for their favorable outcomes in craniofacial applications [19]. Biostability is essential for maintaining structural integrity in the corrosive environment of the human body. Mechanocompatibility is equally important to prevent stress shielding, which can compromise bone integrity adjacent to the implant. This phenomenon is minimized through careful load distribution. The implants must also be capable of enduring high-temperature sterilization and prolonged storage without degrading, ensuring their readiness for surgical use. Manufacturing considerations, including the machining and additive production of large and intricate components, further informed the design process. To enhance performance and integration, the implants underwent specialized surface treatments. Polishing was applied to areas in contact with dynamic tissues, such as eye muscles, and to surfaces within the oral cavity to prevent plaque accumulation and facilitate cleaning. A HadSat (diamond-like carbon) coating was applied to the condylar surfaces to promote biocompatibility and reduce friction. Sandblasting ensured optimal surface roughness for osseointegration and soft tissue integration, enhancing the stability and functionality of the reconstruction.

Virtual Surgical Planning

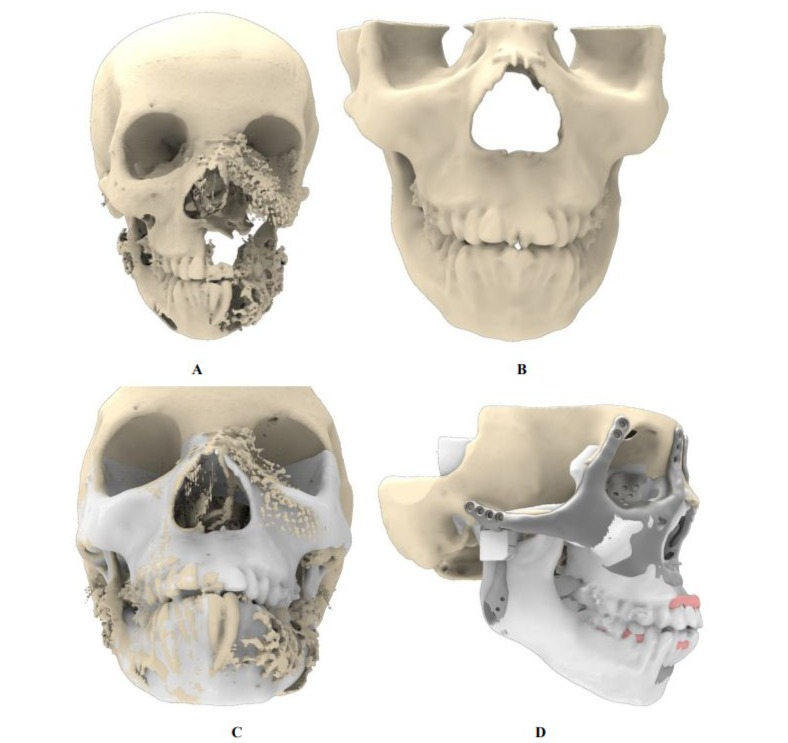

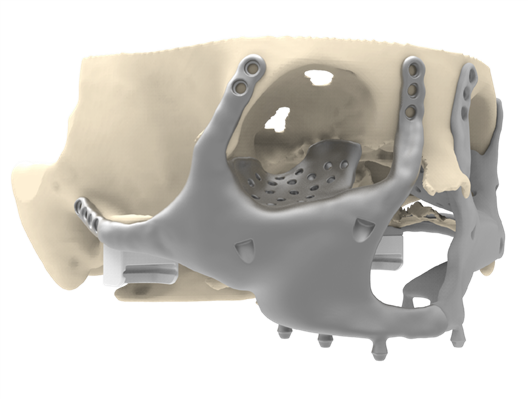

The reconstruction encompasses the re-creation of multiple craniofacial structures, including the zygomatic bone, maxilla, orbital floor, upper and lower dentition, TMJ, mandible, and palatal bone. The design incorporates plans for the reattachment of key muscles, including the buccinator, genioglossus, geniohyoid, and temporalis. Reattaching these muscles ensures that facial mobility and function are preserved, enabling both functional and aesthetic recovery. The aesthetic reconstruction relied on pre-existing CT scan data of 2015 to create a natural and symmetrical design. The relatively intact right side of the patient’s face was mirrored around the midsagittal plane through nasion, basion and the dental midline. This mirroring made the reconstruction of the left side possible. The mirrored reconstruction was adjusted to fit the current craniofacial anatomy, ensuring alignment with key anatomical landmarks such as jaw angles, maxillary and mandibular dentition, orbital and nasal structures. This foundational design served as a blueprint for both surgical and implant planning, ensuring a harmonious blend of functionality and aesthetics (Figures 2, A-D).

Figure 2: Creation of the reference skull based on the 2015 CT scan. (A) Craniofacial defect as documented in 2015. (B) Reference skull used as design blueprint, constructed through mirroring and targeted smoothing techniques. (C) Superimposition of reference skull onto the 2015 skull, demonstrating preservation of key anatomical structures including the gonial angle, occlusion, chin, nasal contour, and orbital volumes. (D) Final implant design overlaid on the reference skull, highlighting adherence to the original anatomical features.

Implant Design Principles

The implant design process balanced the advantages and limitations of using large versus small components. Larger implants reduced the number of connections and potential misalignments, enhancing long-term stability. However, their manufacture and

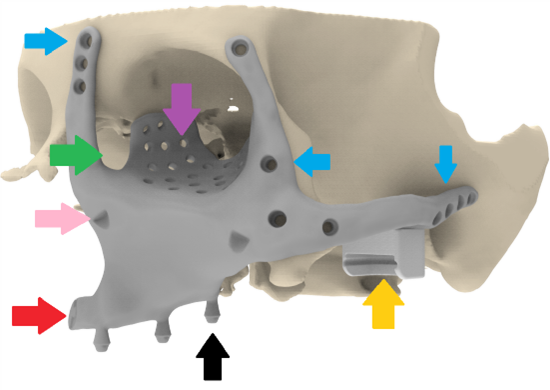

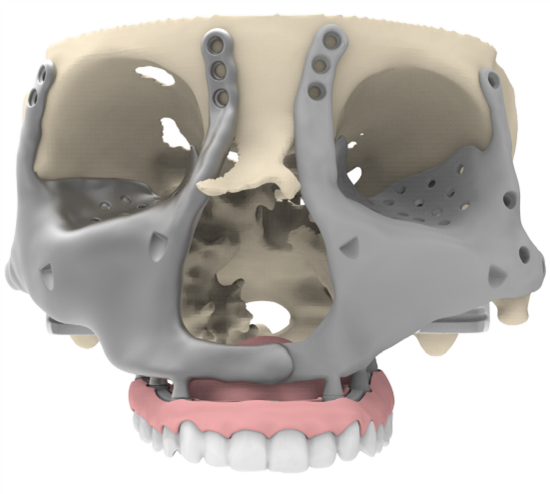

surgical placement were more challenging. Smaller components simplified production but increased operative complexity and alignment challenges. Ultimately, a three-part design was selected, optimizing manufacturability, surgical ease, and long-term implant stability. Additive manufacturing constraints, such as build volume and orientation, were carefully managed during the design phase. The orbital cavity volume was determined from the patient’s previous CT scan to ensure accurate anatomical reconstruction. Drainage openings were incorporated into the design to facilitate the efficient outflow of exudate. An additional recess was included to accommodate the nasolacrimal duct, preserving its function (Figure 3). The implant design carefully maintains a safe distance from the optic nerve to avoid any potential compromise of visual function. Furthermore, the transition between the implant and the remaining bone is smoothed to ensure seamless integration and reduce the risk of irritation or structural complications. Surgical planning must prioritize infection mitigation strategies and ensure precise implant fitment, including the sequencing of placement, incision planning, fixation techniques, and multi-piece assembly where necessary. Functional restoration of dentition, palatal integrity, and surface treatment of the implant to reduce fibrosis and exposure risks must be considered. Additionally, the implant should facilitate soft tissue adhesion to prevent upper lip retraction and optimize postoperative outcomes. A puzzle structure has been implemented at the nose as an intraoperative reference between the two midfacial components.

For an easy placement of the midface components impactor indentations have been added (Figure 3). Attention to these details ensures a comprehensive approach, balancing mechanical reliability, anatomical restoration, and functional optimization in mandibular reconstruction Enthesis reconstruction needs scaffolded areas in the prosthetic components. Attaching a muscle or tendon (or enthesis) to a metallic implant is much more difficult than simply anchoring a tendon to native bone. The “bone-to-tendon” (or muscle-to-implant) interface must deal with differences in mechanical stiffness, stress distributions, micromotion, and biological integration (fibrous vs direct bone attachment). 3D-printed titanium (for example Ti6Al4V alloy) allows tailoring of porosity, lattice structure, surface topography. This can enhance osseointegration (bone ingrowth) and potentially support more robust enthesis/muscle attachments. For instance, larger pores, interconnected structure, rough surfaces all help bone ingrowth. Studies show porous titanium scaffolds can mimic trabecular bone structure and support osteoblast activity [20,21]. The concept of incorporating a porous lattice/cage within the titanium implant, loading it with autologous bone/ stem cells and then suturing the tendon/enthesis element to that scaffold (before full bone union) is a clever hybrid engineering/ biologic strategy. Clinically, if successful, this opens the door to muscle re-attachment to prosthetic components (not just in TMJ but potentially other joints/orthopaedic reconstructions) which may improve functional outcomes (not just passive motion, but active muscle force transfer). Mommaerts mentions “technique has potential applications in orthopedic alloplastic reconstruction” [20,21].

Figure 3: Placement of the left midface component. The implant is shaped according to the reference skull geometry reconstructed from a 2015 CT scan. Key design features include: three multi-unit interfaces for connection to the dental prosthesis (black arrow); fixation screw holes positioned in regions of highest bone quality (blue arrows); orbital support incorporating drainage holes (purple arrow) and dedicated space for the lacrimal duct (green arrow); impaction platform to facilitate accurate intraoperative seating (pink arrow); a puzzle-type structure beneath the nasal aperture for intraoperative alignment (red arrow); and a Condyle-in-a-Box enabling subsequent TMJ reconstruction (yellow arrow).

Prosthetic Joint Geometry

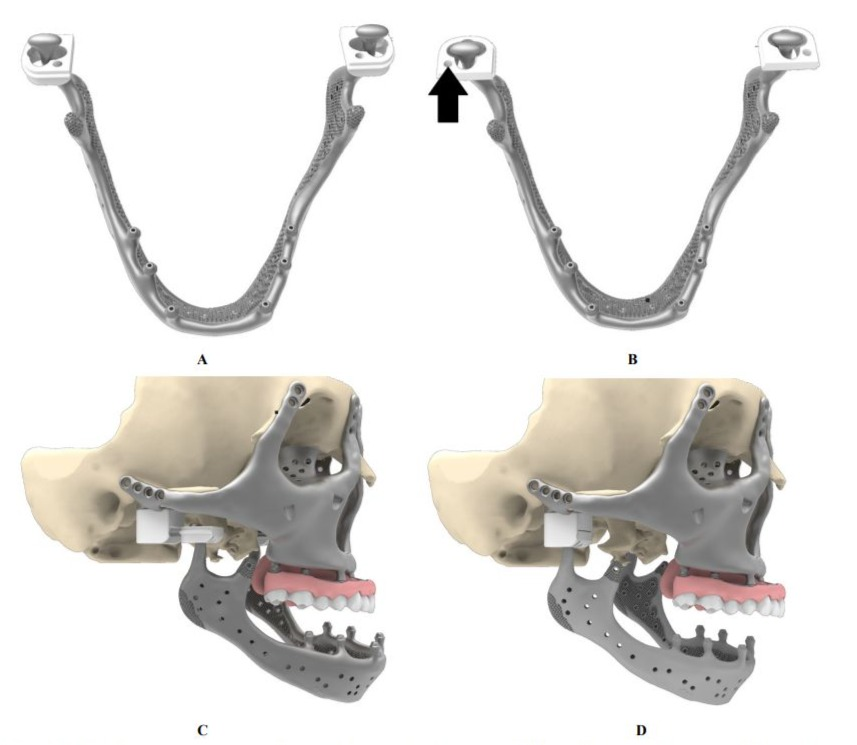

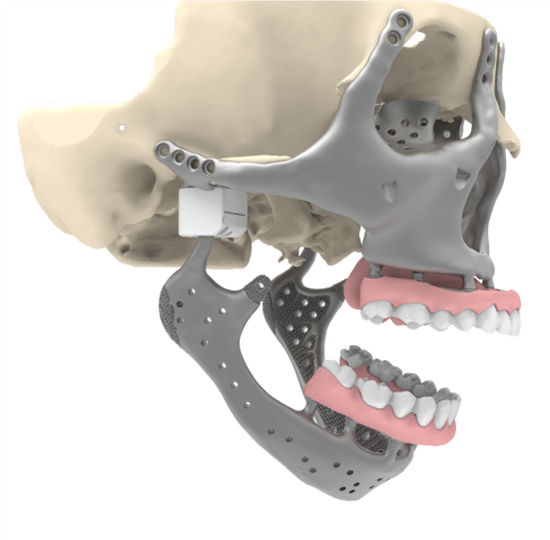

The reconstruction of the mandible required careful integration of biomechanical, surgical, and functional principles. Designing an effective mandibular suspension system was of particular importance. The implant must be lightweight yet mechanically robust, capable of withstanding physiological loading while maintaining minimal thickness to respect both aesthetic and anatomical constraints. Given that the average human mandible weighs approximately 108 g [22], weight-reducing perforations were incorporated to decrease mass without compromising structural strength. For comparison, the first prototype had a weight of 112gr (160gr including the dental prosthesis). The finally implanted mandible had a weight of 69gr (112gr including the dental prosthesis). Figure (4. A,B). The final mandible design incorporated three suspension mechanisms: at the condyles, at

the coronoid processes with enthesis reconstruction of the temporalis muscles, and at the dental prosthesis using elastic stabilization with rubber bands. For condylar suspension, three concepts were evaluated. Suture suspension, commonly used in extended temporomandibular joint reconstruction provides a simple and reliable solution, particularly in unilateral cases [23]. The fixed hinge principle establishes a controlled pivot that prioritizes rotational motion but restricts translational mobility and limits intraoperative maneuverability. The Condyle-in-a-Box principle (Figure 5, A-D) secures the condyle within a structured housing, maintaining stability while preserving rotational and translational joint mechanics, including protrusive and laterotrusive movements. By closely emulating natural temporomandibular joint function, it minimizes displacement risk and improves articulation reliability. The improved freedom of movement also enhances surgical tolerance during placement. Surgical implementation of the Condyle-in-a-Box system proceeds in four coordinated steps. First, the lids of the boxes are slid over both condyles. Next, they are rotated and elevated in one movement to prepare for mandibular positioning. Afterward, the lids are repositioned within their respective boxes, and final closure is achieved with a screw that provides additional retention (Figure 5, A-D). To restore masticatory, respiratory, and phonatory functions, reattachment of essential muscular structures—including the temporalis, buccinator, pterygo-masseteric sling, mylohyoid, genioglossal, geniohyoid, and digastric muscles—must be facilitated. The first mandibular design, with dimensions of approximately 12 mm in height and 8 mm in width, provides sufficient surface area for this muscular reattachment.

A

B

Figure 4: Photographs of two produced patient-specific mandible implants featuring HadSat diamond-like coating on the condylar surfaces (red arrow), sandblasted regions for enhanced soft-tissue and bone integration (orange arrow), and polished zones to accommodate dynamic soft-tissue movement while minimizing plaque accumulation (black arrow). (A) First-generation mandible design with robust, bulky geometry and scaffolding located at anatomical muscle insertion sites, including the medial pterygoid, temporalis, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, digastric, and masseter (112 gr); (B) Redesigned mandible with expanded scaffolding areas to improve surgical manoeuvrability, reduced overall thickness, and integrated strut-based reinforcement, resulting in a lower weight (69gr).

Figure 5: Mandibular suspension by Condyle-in-a-Box principle. A) Placement of lids over the condyles B) Twisting lids upwards placing condyles in position (black arrow indicates space for assembly screw). C) and D) Sliding lids in the box before closure with an assembly screw.

These dimensions further supported the creation of an aesthetically pleasing and symmetrical mandibular contour while ensuring adequate structural integrity for grown healthy adults. When the first mandible was delivered, it was deemed too heavy and a reduction in weight was requested. Paradoxically, the initial design weight had been determined based on FEA simulations of mandibular segment replacements, which indicated that higher mass and thickness were required to withstand expected physiological loads. These contradictory requirements—clinical demand for a lighter construct versus biomechanical evidence supporting a heavier one—

complicated the engineering process and necessitated prioritization of one over the other. Following careful evaluation, the decision was made to further reduce the implant weight to 69 g. This was achieved by substantially decreasing the overall thickness of the construct and incorporating a markedly larger number of scaffolding regions while preserving structural integrity through strategically oriented strut structures. Several considerations justified this choice. First, additional scaffolding areas increased surgical flexibility by providing more opportunities for effective muscular reattachment. Second, the patient’s exceptionally low body weight (35 kg at the time), far below the European average, implied reduced absolute masticatory forces compared with those assumed in standard FEA models. Third, the anticipated muscle damage suggested that maximal bite forces would be considerably lower than in a healthy mandible, reducing the mechanical demands on the implant. An additional advantage of this redesign was the enlargement of the suture holes, which facilitated more accessible and reliable intraoperative suturing. Implant design should account for the spatial requirements of the auditory canal, ensuring a compact profile without compromising mandibular functionality or aesthetics. Superior support beneath the orbital region is essential for preserving visual alignment and minimizing enophthalmos risks.

Surgical Workflow

The surgical procedure followed a systematic approach. The initial step involved the resection of the affected mandible, maxilla, and titanium mesh. The skull base was then prepared for the fixation of the implants. Sequential placement of midface components (Figure 3, Figure 6 ), upper denture (Figure 7), condyle boxes (Figure 5D), and the mandibular reconstruction followed. (Figure 8), The procedure is concluded with the closure of the condyle boxes and final adjustments to ensure proper articulation and implant fit. The manufactured result is shown in Figure 9 on a demonstration skull.

Figure 6: Placement of the right midface component. With identical features as the left midface component (See Figure 3).

Figure 7: Placement of the maxillary dental prosthesis. It restores the upper dentition, guides accurate midface positioning as an external reference, and provides anchorage points for elastic support between upper and lower dentition (not depicted).

Figure 8: Placement of the mandibular dental prosthesis. Including anchorage points for elastic support at dentition (not depicted).

Figure 9: Manufactured implants with the prototype mandible of 112 gr. Anchorage point for elastic suspension at dentition have been added later on.

Discussion

The reconstruction presented here demonstrates the capacity of advanced implant engineering to address severe craniofacial deformities caused by polyostotic FD. Traditional management of FD varies from conservative recontouring to radical excision, depending on lesion extent and functional impairment. Valentini et al. noted that conservative approaches may suffice for localized disease but reported that radical surgery is justified when deformity compromises vital structures or produces significant aesthetic disturbance [1]. Given the extensive involvement spanning the mandible, maxilla, and zygomatic complexes in our patient, a conservative approach would have been inadequate. Several groups have demonstrated the benefits of computerassisted planning for FD recontouring. Wang et al. used surgical navigation to improve precision in maxillofacial FD correction [2], while Matsuo et al., and Guatta and Scolozzi highlighted the use of mirrored virtual models in Le Fort osteotomies and fronto-orbital asymmetry correction respectively [3,4]. In contrast to these bonepreserving strategies, our reconstruction required a comprehensive resection approach followed by full prosthetic replacement of multiple craniofacial units. Radical excision of orbito-cranial FD with titanium reconstruction, as reported by Fadle et al., achieved stable aesthetic and functional outcomes with low recurrence [5]. However, re-growth into titanium occurs, as documented by Wu et al., who described FD invasive proliferation through orbital mesh [6]. These findings reinforce the necessity for durable design principles in long-term craniofacial reconstructions and underscore the unpredictability of FD behavior. In reconstructing the mandible and TMJ, we drew on established principles from alloplastic joint replacement. De Meurechy and Mommaerts have shown that modern TMJ prostheses rely on predictable materials and kinematics that mimic rotational and translational joint motion [8]. Their review emphasized the importance of UHMWPE– titanium couples in minimizing wear and maintaining long-term function [9]. Our Condyle-in-a-Box mechanism extends this concept by embedding the condylar head within a guided housing, facilitating controlled articulation and mitigating risk of mechanical displacement. Additionally, the reconstruction incorporated design principles derived from AMSJI frameworks.

Mommaerts demonstrated that additively manufactured titanium implants could restore dental support without bone grafting in severely atrophic maxillae [10], later refining implant geometry through finite element analysis to reduce stress shielding while improving osseous stability [11]. Subsequent multicenter evaluations by Van den Borre et al. revealed minimal bone remodeling around AMSJI devices [12], favorable clinician- and patient-reported outcomes [13], and sustained improvement in oral health quality-of-life measures [14]. These results justify the use of perforated, lightweight frameworks for large-scale craniofacial reconstruction. Soft tissue response is equally critical. Several studies reported mucosal recession risk associated with AMSJI devices, especially in thin mucosal biotypes [15,16]. Rinaldi et al. and Mommaerts emphasized the importance of optimized suturing, flap management, and multi-component segmentation to reduce soft tissue strain and promote healing [12,17]. These principles influenced our final implant design, including polished intraoral surfaces, sandblasted bone-contact areas, and interlocking segments for precise intraoperative alignment. In the clinical evaluation of soft tissue dynamics, attention has predominantly focused on the upper lip, whereas comparatively less emphasis has been placed on the lower lip, where excess skin redundancy was anticipated due to extensive soft tissue stretching. Postoperatively, the upper lip demonstrated a remarkably favorable outcome; however, the lower lip exhibited insufficient tissue coverage, ultimately resulting in persistent lip incompetence. This observation suggests that, in most cases, a slight downsizing of the device is advisable to facilitate reliable soft-tissue coverage. Excess tissue can be safely trimmed postoperatively, whereas augmenting deficient tissue or harvesting from donor sites is considerably more complex and associated with additional morbidity. The present case combines methodologies typically applied in isolated regions—TMJ arthroplasty, zygomatic reconstruction, orbital floor repair, and sub-periosteal dental restoration—into a single panfacial prosthetic system. This degree of integration is rare, as most TMJ prostheses assume a preserved mandibular body, and most sub-periosteal implants assume preserved midfacial support. Our reconstruction required a unified biomechanical framework that allowed the reattachment of essential muscles, restored load transfer through the midface, and simultaneously preserved airway function, ocular support, and dental occlusion.This case highlights the importance of interdisciplinary cooperation and demonstrates that modern additive manufacturing, integrated virtual planning, and personalized biomaterials can provide safe, stable, and functional outcomes even for extreme craniofacial deformities.

Conclusion

This case exemplifies the successful integration of surgical innovation, advanced material science, and engineering precision in addressing a complex craniofacial reconstruction. The process highlights the importance of balancing material properties, biomechanical considerations, surgical maneuverability, and manufacturing constraints to achieve both functional and aesthetic outcomes. This approach demonstrates the necessity of interdisciplinary collaboration between surgical, dental, and engineering experts, setting a benchmark for future alloplastic craniofacial reconstructions.

Funding: Orthoface bv, Prof Mommaerts

Competing interest: Ir Koops and Ir Nevelsteen are biomedical engineers at CADskills bv. Prof Mommaerts is innovation manager and CEO at CADskills bv.

Ethical committee approval: not applicable

Patient informed consent: present

The operation was performed on April 18, 2025. At the time of manuscript submission, eight months postoperatively, the patient was in good clinical condition. The detailed clinical report of the intervention is currently in press in the International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery.

References

- Valentini V, Cassoni A, Marianetti TM (2009) Craniomaxillofacial fibrous dysplasia: conservative treatment or radical surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg 123: 653-660.

- Wang Y, Lin Y, Yu H (2015) Surgical management of maxillofacial fibrous dysplasia with surgical navigation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53: 816-821.

- Matsuo A, Kono M, Toyoda J, Nakai T, Tsuzuki M, et al. (2010) Navigation surgery for Le Fort 1 osteotomy in a fibrous dysplasia patient. Odontology 98: 181-184.

- Guatta R, Scolozzi P (2018) Guided navigation with mirroring for fronto-orbital fibrous dysplasia. J Neurol Surg A 79: 181-185.

- Fadle KN, Hassanein AG, Kasim AK (2016) Orbitocranial fibrous dysplasia: radical resection and titanium mesh reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg 27: e719–e723.

- Wu H, Li J, Xu J, You C, Huang S (2014) Recurring craniofacial fibrous dysplasia invading titanium mesh. J Craniofac Surg 25: 697–699.

- Corsi A, Ippolito E, Robey PG (2017) Bisphosphonate-induced zebra lines in fibrous dysplasia. Skeletal Radiol 46: 1435-1439.

- De Meurechy N, Mommaerts MY (2018) Alloplastic TMJ replacement systems: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47: 743-754.

- De Meurechy N, Braem A, Mommaerts MY (2018) Biomaterials in TMJ replacement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47: 518-533.

- Mommaerts MY (2017) Additively manufactured sub-periosteal jaw implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46: 938-940.

- Mommaerts MY (2019) Evolution of AMSJI design and biofunctionalization. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 48: 108-114.

- Rinaldi M, Van den Borre C, De Neef B (2020) Guidelines on resection guides and personalized sub-periosteal implants. Ann Maxillofac Surg 10: 467-471.

- Van den Borre C, Rinaldi M, De Neef B (2021) Bone remodeling after AMSJI implantation. Biomed Res Int 2021: 6699094.

- Van den Borre C, Rinaldi M, De Neef B (2022) Clinician- and patientreported outcomes after AMSJI. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51: 243250.

- Van den Borre C, De Neef B, Loomans NAJ (2023) Patient satisfaction following AMSJI rehabilitation. J Pers Med 13: 297.

- Van den Borre C, De Neef B, Loomans NAJ (2024) Soft tissue response and recession risk after AMSJI. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 39: 302-309.

- Mommaerts MY (2025) Management of adverse effects after AMSJI. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 126: 102206.

- DiCaprio MR, Enneking WF (2005) Fibrous dysplasia. Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87: 1848-1864.

- Buser D, Schenk RK, Steinemann S, Fiorellini JP, Fox CH, et al. (1991) Influence of surface characteristics on bone integration of titanium implants. A histomorphometric study in miniature pigs. J Biomed Mater Res 25: 889-902.

- De Meurechy N, Verwilghen D, De Brucker Y, Van Thielen B, Mommaerts MY (2021) Lateral pterygoid muscle enthesis reconstruction in total temporomandibular joint replacement: An animal experiment with radiological correlation. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 49: 256-268.

- Mommaerts MY, Deman F, Verwilghen D, De Meurechy N (2025) Lateral pterygoid muscle enthesis reconstruction in alloplastic total temporomandibular joint replacement: An animal experiment with histological verification. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 53: 476-483.

- Korioth TW, Hannam AG (1994) Deformation of the human mandible during simulated tooth clenching. J Dent Res 73: 56-66.

- Gerbino G, Sobrero F, Poelaert R, Borbon C, Ramieri G, et al. (2025) Extended temporomandibular joint prostheses: a retrospective analysis of feasibility, outcomes, and complications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54: 438-447.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.