Why not Silicon? Using Computational Chemistry to Probe why Nature did not Select Silicon for Biomolecules

by Jason C. Cooper, Joshua A. Robertson, Chasity M. Ward, Maureen Kendrick Murphy*

Huntingdon College, Montgomery, AL 36106 USA

*Corresponding author: Maureen Kendrick Murphy, Huntingdon College, Montgomery, AL 36106, USA

Received Date: 01 December 2025

Accepted Date: 05 December 2025

Published Date: 08 December 2025

Citation: Cooper JC, Robertson JA, Ward CM, Murphy MK (2025) Why not Silicon? Using Computational Chemistry to Probe why Nature did not Select Silicon for Biomolecules. Adv Biochem Biotechnol 10: 10136 https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7258.010136

Abstract

While the versatility of carbon bonding allows structures containing chains, rings, and nanotubes, the analogous silicon structures are comparatively unstable and often highly reactive. Carbon chemistry exhibits a rich variety in bonding patterns, with homo- or heteronuclear multiple bonds involving sp-hybridized carbon atoms as found in molecules such as acetylenes, nitriles, allenes and carbon dioxide. The heavier homologues of carbon in Group 14 (Si, Ge, and Sn) of the periodic table were thought incapable of forming multiple bonds because of the less effective pπ-pπ orbital overlap involved in the multiple bonds. Previous molecular mechanics calculations have demonstrated that the lowest energy isomer of Si2H2, disilyne, (the silicon analogue of acetylene) is a hydrogen-bridged non-linear structure, while its carbon analogue acetylene (C2H2) is linear [1]. Although silicon-based life has been the topic of science fiction and astrobiological studies, there are few systematic computational studies of the energies, geometries, and steric constraints exhibited by silicon-substituted molecules of biological interest. We studied fifteen molecules including: methane, ethene, ethyne (acetylene), ethane, benzene, cyclohexane, ATP, caffeine, glucose, Fe+2-protoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester, oxytocin (a small polypeptide),Fe+2-tetraphenylporphyrin, propofol, acetaminophen, and cocaine. The molecules were constructed using molecular modeling and molecular mechanics software including HyperChem 8.0.10 and Spartan ‘06 molecular modeling and computational chemistry software.

Molecular mechanics calculations were performed including minimized energy, bond angles, bond lengths, and lowest vibrational frequency. The molecules studied were constructed by building each molecule in HyperChem and Spartan with carbon atoms and rebuilding each molecule separately again with silicon substituted for each carbon. Comparisons of the relative minimized energies and the bond angles in carbon-based versus the silicon-based molecules were made to provide quantitative data to help describe why nature did not select silicon for biological molecules. Why, at a molecular and structural level, did natural selection favor carbon over silicon for the complex chemistry of life? Could the inability to form strong p(π)-p(π) bonds to create multiple bonds needed in planar geometries that are structurally and mechanistically required in biological systems (heme proteins, DNA bases, and peptide bonds) be one of the many contributing reasons silicon is unable to substitute for carbon in some important biomolecules? This paper will utilize computational chemistry methods (e.g., ab initio calculations, density functional theory, minimized energy and bond angle calculations) to compare the fundamental energetics, bonding, and steric characteristics of analogous carbon and silicon molecules, demonstrating that steric, along with well-known thermodynamic, and kinetic factors likely play a role in why silicon is unsuitable for the high-specificity, rapid metabolic processes required for life on Earth. This paper presents a computational approach to the implications of silicon on conformational structures and the possible use of silicon as a bioisostere in the pharmaceutical industry when it is incorporated into potential new drugs. The challenges, limitations, and future directions in these computational methods are presented.

Introduction

Although there are drawbacks to invoking silicon as the basis for life, some silicon-based chemicals have been found to be more stable than the equivalent hydrocarbons in sulfuric acid-rich and sulfur-rich environments [1-11]. The idea that life could be based on silicon rather than carbon was first proposed in 1891 by the German astrophysicist Julius Scheiner [12]. There are diatoms which exist in nature and contain silicon for structural integrity [10]. Of the molecules identified in interstellar space, 84 are carbon-based and 8 are silicon-based [5]. In addition, the ratio of abundance of silicon to carbon in the earth’s crust is 925 to one, whereas the cosmic ratio of carbon to silicon is 10 to one [5]. Silicon has a larger atomic radius and larger mass than carbon. Currently, silicon lacks the chemical versatility in forming stable bonds required for known biochemical metabolism on earth. Long chain silanes spontaneously decompose and are often highly reactive with water. Silicones (containing Si-O-Si) however, are very stable. No one has yet isolated a stable silicon analogue of a pure protein amide bond, although attempts to isolate a silicon-based polypeptide are in progress [6,7]. The unusual structure of disilyne (Si2H2) predicted theoretically, showed the ability of silicon-hydrides to adopt unique structures [1,2,13]. We examined a series of silicon analogues of carbon-based molecules of biochemical interest and compared the relative minimized energies and structures of our selected molecules with their carbon counterparts. Our results present some silicon structures that although may offer alternatives to carbon-based life (extremophiles) in extreme environments, non-aqueous solvents, and interstellar space, these computergenerated structures demonstrate the innate difficulty of silicon in forming strong pπ-pπ bonds required for many required functional biomolecules on Earth.

Background-A Comparison of Carbon and Silicon Properties

An excellent and comprehensive 2020 paper on the topic of silicon by Petkowski, Bains, and Seager [11] concluded that purely silicon-based life is highly unlikely in most planetary environments, particularly those with water, suggesting silicon may serve as a minor structural component in extreme conditions. The study systematically explored the possibility of silicon serving as a building block of life and evaluated the potential of silicon as a biological scaffold in various solvents using a combinatorial approach [14]. Our studies herein are based upon the theoretical study of silicon-substituted biomolecules with respect to steric, geometric, and energetic considerations. Silicon is the closest analogue of carbon. Silicon and carbon are tetravalent atoms that form primarily covalent compounds. However, from a chemical and biochemical perspective, there is little similarity between Si and C that goes beyond the statement learned in organic chemistry that both elements “can form four covalent bonds” [11]. The covalent radius of a silicon atom is larger than that of carbon which results in generally longer bond lengths and different bond angles (Table 1).

|

Property |

Carbon (C) |

Silicon (Si) |

|

Electron Configuration |

1s22s22p2 |

1s22s22p23s23p6 |

|

Covalent Radius |

77 pm |

117 pm |

|

Electronegativity (Pauling Scale) |

2.50 [Cδ-←Hδ+] |

1.8 [Siδ+→Hδ-] |

|

Coordination Number (stable compounds) |

1, 2, 3, 4 |

3,4,5,6 |

|

Bond Dissociation Energies |

C-O: 358 kJ/mol C-Si: 318 kJ/mol C-H: 411 kJ/mol C-C: 347 kJ/mol |

Si-O: 452 kJ/mol Si-C: 316 kJ/mol Si-H: 318 kJ/mol Si-Si: 300 kJ/mol |

|

Bond Lengths |

C-O:143 pm C-Si:185 pm * C-H:109 pm C-C:154 pm C=C:134 pm C≡ C:120 pm *(longer and slightly weaker than C-C) |

Si-O:163 pm Si-C: 185 pm * Si-H:148 pm Si-Si:234 pm, depends on substituents Si=Si:214-229 pm Si≡Si:206 pm

|

|

Multiple Bonds |

C=C, C≡C, aromatic C |

Si=Si, Si≡Si, aromatic Si |

|

Hexacoordinate and Pentacoordinate

Systems |

Unstable |

Known and stable (in some cases even in

aqueous solution) as charged and uncharged species |

Table 1: Comparative Physical and Chemical Properties of Carbon and Silicon.

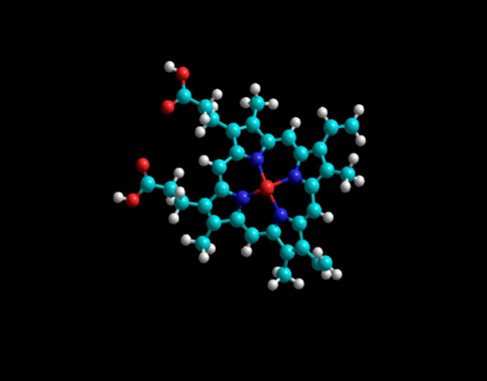

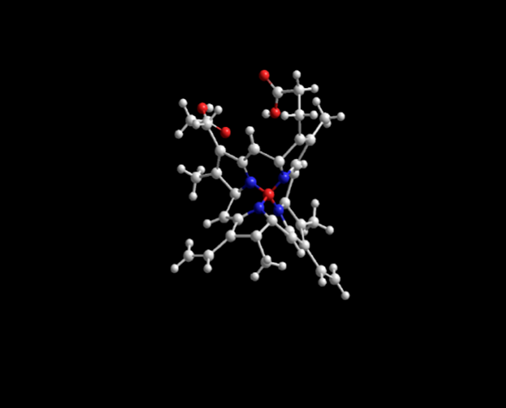

Different bond lengths and angles have especially large effects in ring structures containing silicon atoms, resulting in distinct ring conformation as compared to their carbon-containing analogues. In our computational research, these large effects in ring structures and distinct ring conformations containing silicon atoms were seen in the comparison of the energy-minimized structures of Fe+2protoporphyrin IX containing carbon versus silicon atoms in the molecule See (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Lowest energy geometry for Fe+2-protophoryin IX with carbon atoms in light blue. Note the planar porphyrin ligand with four planar pyrrole rings. Emin=5726.124 kJ/mol.

Figure 2: Lowest energy geometry for Fe+2-protophoryin IX with silicon atoms (grey) substituted for carbon atoms. Note the non-planar porphyrin ligand with four twisted pyrrole rings. Emin=11209.94 kJ/mol.

From a bonding perspective, silicon has the availability of lowlying 3d orbitals that allow silicon to form compounds with five- or six-coordinated silicon atoms that carbon is unable to achieve [15-17]. Silicon is more electropositive (and less electronegative) as compared to C, N, O, and H. The higher electropositivity (and lower electronegativity) of Si creates an electron-deficient center in silicon and results in a stronger bond polarization as compared to analogous carbon bonds, or in a reversed bond polarization of the C-H and Si-H bonds (Table 1). As a result of those differences, most bonds that silicon forms with non-metals are more strongly polarized than their carbon counterparts and thus more susceptible to electrophilic and nucleophilic attack. For example, silicon tetrachloride (SiCl4) is hydrolyzed almost instantly in water, whereas carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), is stable for years in the presence of water. Silanes (SiH4, Si2H6, etc.) are stable as pure chemicals for years but are very sensitive to water in the presence of trace alkali. Reactions of disilane (Si2H6) and ethane (C2H6) with oxygen are exothermic, but ethane (C2H6) can mix with oxygen at 200 °C without reacting, whereas disilane (Si2H6) spontaneously combusts in air at 0 °C [17]. An extensive overview of the physical and chemical properties of carbon and silicon, including their respective bond and common functional group reactivity can be found at: Petkowski, JJ, Bains, W, and Seager, S. (2020) On the Potential of Silicon as a Building Block for Life, Life (Basel)2020 Jun 10;10(6):84.

Experimental Methods

The method of investigation used HyperChem 8.0.10 and Spartan ’06 molecular mechanics software to build carbon-based biomolecules commonly found in nature, and then calculate minimized energies, necessary bond lengths, dipole moments, and bond angles. Each molecule being investigated was built from scratch, replacing the carbon atoms with silicon atoms. The same calculations were carried out, and the results compared. Additionally, a comparison of methane and silane was carried out to assess our methods. Geometric optimization, minimized energies, bond angles and vibrational analysis were performed on each molecule.

Selection of Molecules for Study

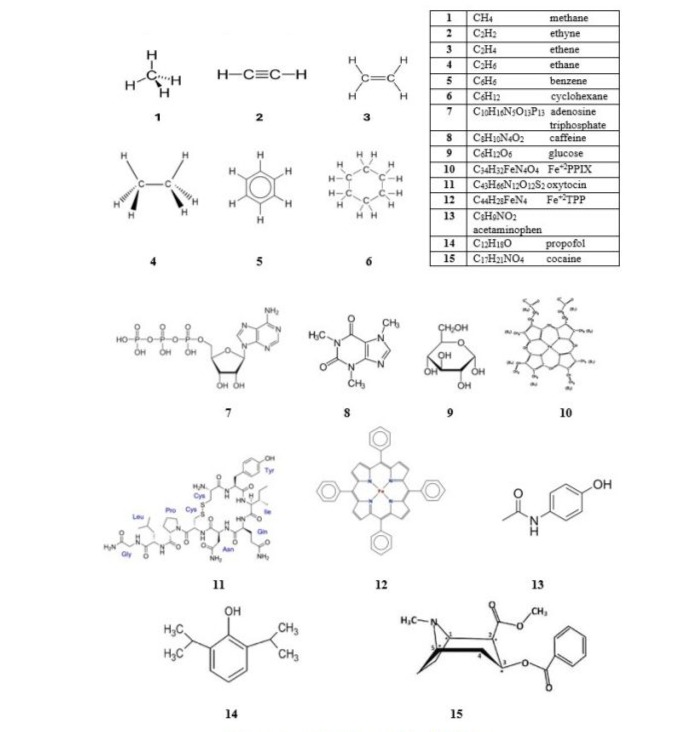

(Figure 3) lists and depicts the fifteen (15) carbon molecules selected for our study. These molecules were selected based upon their representation in chemistry and biochemistry and pharmacology as important biomolecules. Fifteen (15) additional molecules were studied, each of which was the silicon analogue of the corresponding carbon molecule. Molecules 1-6 are classical organic molecules, which also have accessible silicon analogues, either experimentally and/or theoretically for comparison. Molecules 7-15 were selected for the following reasons:

Molecule 7-Adenosine triphosphate is a molecule that carries energy for cellular processes and is often called the “energy currency” of the cell. It is generated through cellular respiration and provides energy for essential functions like muscle contraction, nerve impulses, and chemical synthesis.

Molecules 8 and 9-Caffeine and glucose are chemicals that play important roles in the human body. Glucose is a simple sugar and a primary source of energy for the body’s cells, produced from the carbohydrates in food. It is transported to cells via the bloodstream, and its levels are regulated by hormones like insulin. Caffeine is a central nervous stimulant and acts by blocking the binding of adenosine at a number of adenosine receptor types, inhibiting the centrally depressant effects of adenosine and enhancing the release of acetylcholine. Caffeine has a three-dimensional structure similar to that of adenosine, which allows it to bind and block its receptors.

Molecules 10-12: Fe+2-protoporphyrin IX serves as an active site for many heme proteins. Oxytocin is a natural hormone and polypeptide composed of nine amino acids connected by peptide bonds. It stimulates uterine contractions in childbirth and lactation after infant birth. It also affects aspects of human behavior and the male and female reproductive systems. Fe+2-tetraphenylporphyrin serves as a model compound for hemeproteins and is used widely in porphyrin chemistry.

Molecules 13-15: These molecules (acetaminophen, propofol, and cocaine) were selected as representatives of drugs used by humans. Acetaminophen is a popular pain killer. Propofol is a short-acting intravenous anesthetic used for general anesthesia and sedation in medical procedures and intensive care. It works by enhancing the inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter GABA in the central nervous system, leading to a rapid onset and recovery from its effects. Cocaine is a central nervous system stimulant and tropane alkaloid derived primarily from the leaves of two coca species native to South America.

Figure 3: Carbon Molecules Selected for Study.

Results and Discussion

Our computational study of fifteen silicon analogues of selected carbon molecules resulted in comparative minimized energies and global minima geometries of thirty different molecules. Out of the 30 molecules studied, seven of the fifteen silicon analogues exhibited higher minimized energies than the parent carbon molecules. These molecules are highlighted in yellow on (Table 2).

|

No. |

Carbon Molecule |

Energy of Carbon Molecule, kJ/ mol |

Silicon Analogue |

Energy of Silicon Analogue, kJ/ mol |

Difference in Energy (C Molecule-Si Analogue), kJ/mol |

|

1 |

CH4 methane |

493.8053 |

SiH4 silane |

489.6991 |

4.106174 |

|

2 |

C2H2 ethyne |

5.61534 |

Si2H2 disilyne |

149.8763 |

-144.2609 |

|

3 |

C2H4 ethene |

0.570121 |

Si2H4 disilene |

0.090793 |

0.479328 |

|

4 |

C2H6 ethane |

1079.541 |

Si2H6 disilane |

1032.335 |

47.20554 |

|

5 |

C6H6 benzene |

11.70782 |

Si6H6 silabenzene |

4.453335 |

7.254485 |

|

6 |

C6H12 cyclohexane |

3353.882 |

Si6H12 |

3457.917 |

-104.035 |

|

7 |

C10H16N5O13P13 adenosine triphosphate (ATP) |

7344.6137 |

Si10H16N5O13P13 (Si-ATP) |

8090.587 |

-745.9733 |

|

8 |

C8H10N4O2 caffeine |

1772.385 |

Si8H10N4O2 |

1686.842 |

85.543 |

|

9 |

C6H12O6 glucose |

3709.698 |

Si6H12O6 |

3363.156 |

346.542 |

|

10 |

C34H32FeN4O4 Fe+2PPIX |

5726.124 |

Si34H34FeN4O4 |

11209.94 |

-5483.816 |

|

11 |

C43H66N12O12S2 oxytocin |

19329.79 |

Si43H66N12O12S2 |

17437.68 |

1892.11 |

|

12 |

C44H28FeN4 Fe+2TPP |

2834.213 |

Si44H28FeN4 |

5181.72 |

-2347.507 |

|

13 |

C8H9NO2 acetaminophen |

1517.729 |

Si8H9NO2 |

1325.425 |

192.304 |

|

14 |

C12H18O propofol |

1089.732 |

Si12H18O |

3680.409 |

-2590.677 |

|

15 |

C17H21NO4 cocaine |

8979.11 |

Si17H21NO4 |

9300.797 |

-321.687 |

Table 2: Minimized energies of carbon and silicon molecules studied and energy differences calculated using HyperChem 8.0.10 and Spartan ’06.

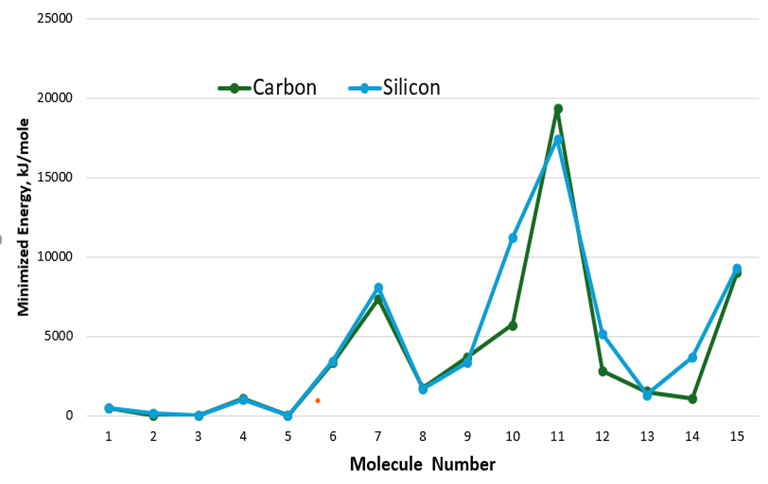

These seven molecules include Si2H2 (disilyne), Si6H12, Si10H16N5O13P13 (Si-ATP), Si34H34FeN4O4 (Fe-SiPPIX), Si44H28FeN4 (FeSiTPP), Si12H18O (Si-propofol), and Si17H21NO (Si-cocaine). These all had nonplanar and sometimes twisted geometries See (Figure 3). Especially in cases in which the parent carbon molecule was aromatic or had aromatic or planar functional groups, the lowest energy geometry of each of the silicon analogues was not planar. A planar “silicon-based peptide bond” does not exist in nature, but scientists have engineered synthetic molecules called silicon-containing amino acids and peptides or used silicon compounds as catalysts to form peptide bonds. (Figure 4) depicts a graph of the minimized energies of the carbon parent molecules and the silicon analogues. On this graph are seven places where the minimized energy of the silicon analogue is larger than that of its carbon counterpart.

Figure 4: Minimized Energy Comparison Between Carbon and Silicon Analogues, (Kj/mole).

(Table 2) emphasizes the large, minimized energy difference between these seven silicon analogues and the parent carbon molecule. In the most extreme case, in which Si was substituted for C in Fe+2-protoporphyrin IX, found in heme proteins, the Si PPIX conformer had a minimized energy of 11,209.94 kJ/mole compared to that of the C PPIX conformer with a calculated minimized energy of 5,726.124 kJ/mole. (Figures 1 and 2) depict the dramatic differences in the geometry of the C-PPIX and the Si-PPIX. Just as silabenzene has been predicted to have a non-planar chair geometry see (Figure 5) below, we observed the same non-planarity in the porphyrin analogues (Molecules 10 and 12) as well as in other molecules studied that required a ring structure or planar geometry.

Figure 5: Comparison of aromaticity in nonplanar silabenzene (top) and planar benzene (bottom) [8].

Based upon our current studies presented herein, we propose the inability of Si to form strong p(π)-p(π) orbital overlap compared to that of carbon is one of the many contributing reasons silicon is unable to substitute for carbon in some important biomolecules. The ability to form strong p(π)-p(π) bonds is essential for the creation of multiple bonds in planar geometries that are structurally and mechanistically required in biological systems such as heme proteins, DNA bases, and peptide bonds. A comparison of p(π)-p(π) bond overlap in carbon and silicon is explained below.

Comparison of C-C vs. Si-Si p(π)-p(π) Orbital Overlap

The key difference in p(π)-p(π) bond formation between carbon and silicon is the effectiveness of the orbital overlap, which is dictated by atomic size.

- Carbon (C-C): Carbon atoms are small, and their 2p orbitals are compact. When they form a pi (π) bond through lateral (side-on) overlap, the orbitals can get very close to each other, resulting in significant and effective overlap. This strong overlap creates stable C=C double bonds, which is why carbon is the backbone of organic chemistry.

- Silicon (Si-Si): Silicon atoms are larger than carbon atoms. Their 3p orbitals are more diffuse and extended further from the nucleus. When two silicon atoms attempt to form a pi (π) bond, the increased atomic size means the parallel p-orbitals are further apart in the resulting sigma-bonded framework. This leads to poor, weak, and less effective lateral overlap.

- In essence, while the type of orbital interaction (side-on p-p overlap) is the same in theory, the extent and strength of the overlap are vastly different due to the larger size of the silicon atom, which makes Si-Si pi (π) bonds much less stable than C-C pi (π ) bonds.

Thermodynamic Considerations

The thermodynamic calculations of Petkowski et al [11]. Showed that the standard energies of formation of Si-containing compounds are generally much higher, and therefore less favorable, than their carbon counterparts (Table 3).

|

Silicon Compound |

Carbon Analogue |

ΔG° Formation kJ/mol (298 K) |

|

|

Silicon |

Carbon |

||

|

Silane SiH4 |

Methane CH4 |

57.2 |

−51.12 |

|

Disilane Si2H6 |

Ethane C2H6 |

127.07 |

−32.25 |

|

Trisilane Si3H8 |

Propane C3H8 |

185.18 |

−23.84 |

Table 3: Some standard energies of formation of Si-containing compounds and comparison with their carbon analogues [11].

From extensive calculations of the energies of formation of many silicon-containing molecules and their carbon analogues, the authors concluded that “Such a high thermodynamic cost of the synthesis of silicon compounds could contribute to the scarcity of silicon in biochemistry; it is not, however, an absolute limitation.” [10].

Conclusions

Our computational studies show that silicon analogues of biological molecules with opportunities for extensive pπ- pπ bonding can adopt unusual structures when compared to the analogous carbon analogues, because Si is unable to form strong p(π)-p(π) orbital overlap compared to carbon. The minimized energy of seven of the fifteen silicon-based biological molecules studied is larger than that of the carbon-based biological molecules. We are extending our computational and energy studies to: (a) include silicon-based polypeptides, carotenoids, and proteins, and (b) incorporate other Group 14 atoms into future models.

References

- Colegrove BT, Schaefer HF III (1990) Disilyne (Si2H2) revisited. Journal of Physical Chemistry 94: 5593.

- DeLeeuw BJ, Grev RS, Schaefer HF III (1992) A comparison and contrast of selected saturated and unsaturated hydrides of group 14 elements. Journal of Chemical Education 69: 441.

- Reynolds, J.E.(1893) Nature 48: 477.

- Wakita K, Tokitoh N, Okazaki R, Takagi N, Nagare S (2000) J. Am. Chem. Soc 23: 5648.

- Bains W (2004) Many Chemistries Could Be Used to Build Living Systems. Astrobiology 4: 137-167.

- Remond E, Charlotte M, Jean M, Florine C (2016) Silicon-Containing Amino Acids: Synthetic Aspects, Conformational Studies, and Applications to Bioactive Peptides. Chem. Rev 116: 11654-11684.

- Benner SA (2004) Is there a common chemical model for life in the universe? Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 8: 676-680.

- Abersfelder K, et al. (2010) A Tricyclic Aromatic Isomer of Hexasilabenzene. Science 327:564.

- Alison A (1968) Journal of British Interplanetary Society 21:48.

- Pace NR (2001) The universal nature of biochemistry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98: 805-808.

- Petkowski JJ, Bains W, Seager S (2020) On the Potential of Silicon as a Building Block for Life. Life 10: 84.

- Darling D, Schulze-Makuch D (2016) The Extraterrestrial Encyclopedia. First Edition Design eBook Publishing; Sarasota, FL, USA: 2016.

- Sekiguchi A, Kinjo R, Ichinohe M (2004) A stable compound containing a silicon-silicon triple bond. Science 305: 1755-1757.

- Bains W, Seager S (2012) A combinatorial approach to biochemical space: Description and application to the redox distribution of metabolism. Astrobiology 12: 271-281.

- Metz S, Burschka C, Platte D, Tacke R (2007) Pentacoordination of Silicon by Five Different Ligand Atoms: Neutral Silicon (IV) Complexes with SiClSONC and SiISONC Skeletons. (2007) Angew. Chem 119: 7136-7139.

- Junold K, Baus JA, Burschka C, Vent-Schmidt T, Riedel S, et al. (2013) Five-coordinate silicon (II) compounds with Si-M bonds (M = Cr, Mo, W, Fe): Bis [N, N′-diisopropylbenzamidinato (−)] silicon (II) as a ligand in transition-metal complexes. Inorg. Chem 52: 11593-11599.

- Stock A (1933) Hydrides of Boron and Silicon. Cornell University Press; Tucson, AZ, USA: 1933.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.