When Love and Lust Collide, Brain Becomes Confused: A Rare Case of Atrio-Oesophageal Fistula Following Cardiac Ablation and Literature Review

by Rachid Attou1, Leticia Al-Kai1, Angela Brunetti1, Ikram Boutrika1, Ahmed Sanoussi2, Andrea Gallerani1, Sohaïb Mansour1, Ayoub Jaafari1*

1Intensive Care Unit Department, C.H.U Brugmann, Belgium

2Cardiac Surgery Department, C.H.U Brugmann, Belgium

*Corresponding author: Ayoub Jaafari, Intensive Care Unit Department, C.H.U Brugmann, Belgium

Received Date: 02 August 2024

Accepted Date: 06 August 2024

Published Date: 08 August 2024

Citation: Attou R, Al-Kai L, Brunetti A, Boutrika I, Sanoussi A, et al (2024) When Love and Lust Collide, Brain Becomes Confused: A Rare Case of Atrio-Oesophageal Fistula Following Cardiac Ablation and Literature Review. Ann Case Report. 9: 1923. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.101923

Abstract

Traditionally, atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment has been based on heart rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation. Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) is now a mainstream therapeutic option for patients who have failed or been refused medical treatment. While recent trials have shown some decrease in mortality after catheter ablation (CA) compared to medication, the procedure still incurs significant complications and mortality rates. Atrio-oesophageal fistula (AOF) is a scarce but tragic complication usually present 1-4 weeks post-RFCA that may threaten a patient’s life if diagnosed late. In this paper, we report a rare case of atrio-oesophageal fistula manifested by persistent chest pain and loss of consciousness and a literature review.

Keywords: Atrio-Oesophageal Fistula; Atrial Fistula; Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation.

Introduction

Over the last few years, substantial improvements have been achieved in atrial fibrillation (AF) detection and management. AF represents one of the most widespread arrhythmias and is often successfully managed with medical treatment [1,2]. In certain cases, patients may require an interventional approach of isolating the pulmonary veins around their ostia by catheter ablation (cryoablation or radiofrequency) [3]. The procedure generally has a low complication rate, with some including tamponade/pericardial effusion, vascular lesions, stroke, pulmonary vein stenosis, and less commonly, atrio-oesophageal fistula (AOF) [3]. AOF is an infrequent but dramatic complication that can be life-threatening if diagnosed late. First described in 1970, it typically arises after radiofrequency ablation (RFA) through the atrial wall and into adjacent oesophageal tissue alongside the posterior left atrium, both in open-heart surgery and in percutaneous catheter ablation (PCA) procedures [4,5]. In our view, the incidence of AOF after PCA fluctuates between 0.01% and 0.2%, whilst it reaches 1% to 1.5% in patients undergoing surgical ablation [2-5]. Given the extremely high morbidity and mortality rates of this entity, it requires prompt medical and surgical treatment once diagnosed. Herein we report a scarce case of atrio-oesophageal fistula manifested by persistent chest pain and rapid loss of consciousness and its therapeutic management. We also have provided an overview of the literature covering the clinical presentation of AOF, diagnostic investigations, underlying pathophysiology, and associated medical and surgical approaches.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old patient was admitted to emergency with central thoracic pain, constrictive and radiating to the jaw. On history, the patient explained that since this morning, the pain had appeared suddenly and had never stopped. No other complaints were noted. His notable medical and surgical history included persistent atrial fibrillation, which had been ablated by radiofrequency 2 weeks previously and treated with a flecainide-type anti-arrhythmic agent and anticoagulated with novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC), arterial hypertension treated with an anti-calcium agent, and dyslipidaemia treated with a statin. On admission, the parameters were as follows: blood pressure of 149/100mm Hg, heart rate of 98 beam per rate, sub-pyretic at 37.1°C and sweating, ambient O2 saturation of 92%, Glasgow score of 15/15 and normal blood glucose of 98mg/dL. Cardiopulmonary auscultation, as did the abdominal and neurological clinical examinations, revealed no abnormalities.

Bearing in mind the patient’s condition at the time of consultation, complementary exams were carried out. An electrocardiogram revealed no abnormalities in atrioventricular conduction. Biological tests conducted in the emergency department showed a reassuring haemogram, normal white blood cells, no inflammatory syndrome, D-dimer levels at 1100, normal renal and liver function, and troponins measured at 13.8ng/L (N<14.0) but rechecked at 1 and 3 hours to 54ng/L and 72ng/L respectively. Bacteriological mapping was also performed, with blood cultures returning negative, a reassuring urine examination, and a chest X-ray showing no infectious sites. Given the persistent painful symptoms despite analgesics and the partial benefit of nitrate, as well as positive troponin kinetics, the final diagnosis of NSTEMI-type acute coronary syndrome was made and the patient was admitted to the hospital.

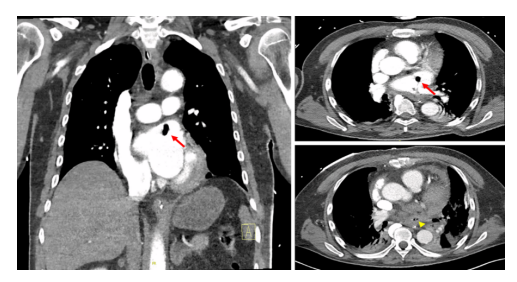

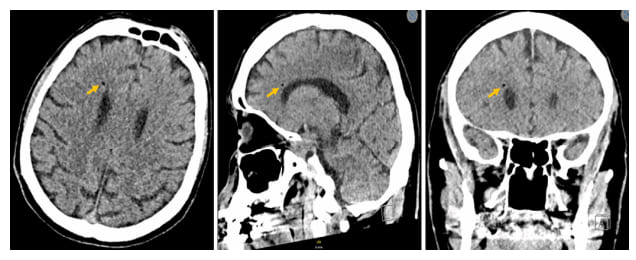

One day after admission, the patient deteriorated. He became comatose with a Glasgow score of 3/15 (E1M1V1). His clinical parameters showed a blood pressure of 98/74mm Hg (mean 63mm Hg), a heart rate of 122 beats per minute, a temperature of 38.2°C, and a tachypnoea of 36 per minute. The clinical examination provided no more information than the day before. The patient was rapidly transferred to the intensive care unit, where he was intubated and put on mechanical ventilation, as well as vasopressor support. A new blood test and bacteriological mapping were carried out immediately, revealing normocytic normochromic regenerative anaemia at 8.8g/dL, hyperleukocytosis at 21,700/µL (N 3,50011,000), inflammatory syndrome at 268.7g/dL (N <5.0), slightly disturbed coagulation, AKIN I acute renal failure, troponins at 2434ng/dL and cytolysis and cholestasis at 3x normal. A chest CT scan revealed a hyper dense image with an aeric centre in the left atrium and the presence of air bubbles in the lower third of the oesophagus (Figure 1). A brain CT scan showed the presence of gaseous emboli scattered throughout the cerebral parenchyma (Figure 2). Lumbar puncture revealed no underlying infection. The diagnosis of atrio-oesophageal fistula complicated by massive septic shock was retained. The patient was treated with broadspectrum antibiotics. Surgical management was performed with the cardiovascular and gastroenterology teams. During the surgery, extensive vegetation associated with a necrotic fistulous orifice approximately 1.5 cm in diameter was found in the posterior wall of the left atrium close to the oesophagus. The atrium was closed and an oesophageal prosthesis was inserted.

Figure 1: Thoracic angio-scan revealed a hyperdense image with an aeric centre in the left atrium measuring 8 x 10 mm (red arrow) and the presence of air bubbles in the lower third of the oesophagus (yellow head arrow), suggesting an atrio-oesophageal fistula.

Figure 2: CT scan of the skull shows the presence of air bubbles in the right paraventricular region suggestive of gas embolism.

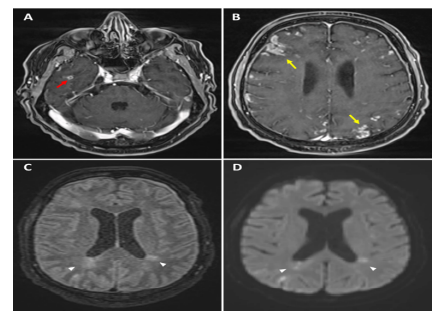

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (RMN) revealed a micro-abscess in the right temporal region after injection of contrast medium (A, red arrow), associated with multiple cortical and parenchymal enhancement (B, yellow arrows) and multiple recent/ semi-recent ischaemic lesions in diffusion and FLAIR sequences (C, D, white head arrows).

Discussion

Atrio-oesophageal fistula (AOF) is a scarce but serious complication of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation. Despite a rise in operators’ experience of radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA), the mortality rate remains very high [6]. Symptoms most commonly experienced include fever, chest pain, melena and/or haematemesis, and more critically, septic shock and neurological deficits (as the fistula often acts as a one-way valve for gas or septic emboli) as in our patient (Figures 2-3) [7]. Unfortunately, the delayed onset of symptoms (up to 3-5 weeks after ablation) and their lack of specificity often delay diagnosis. Our case is unique considering that AOF is an infrequent entity, and the patient’s a-specific clinical presentation and rapid deterioration.

Ablation of AF involves the creation of radiofrequency lesions around the ostia of the pulmonary veins. Oesophageal complications may reach an average of 44-47%, regardless of the type of procedure (surgical or percutaneous ablation) [8]. Nonetheless, the type of energy delivered and its impact on oesophageal lesions are contentious. Several studies have reported on the occurrence of AOF after RFA and cryoablation, without showing an advantage of one technique over the other [5]. The oesophagus is situated at the posterior part of the left atrium wall (0.9 ± 0.2 mm) and the pulmonary veins. According to the literature, the aetiology of AOF has been attributed to the high sensitivity of the intestinal mucosa to thermal injury as opposed to the relative resistance of the cardiac muscle, with tissue damage originating in the oesophagus and progressing to the left atrium [9,10]. Consequently, the proximity between both explains the risk of thermal injury during the procedure. Moreover, other mechanisms may play a role in the development of AOF as follows; luminal infection, ablationinduced or aggravated acid reflux, and ischaemic injury by thermal occlusion of the terminal arterioles [11]. Damage may occur to the left atrium and oesophagus, but the mechanism of the fistula appears to be from the oesophagus to the atrium. To date, no isolated injury to the left atrium without AOF has been reported, whereas oesophageal perforation alone is a rare but well-known complication [12].

An early diagnosis and a detailed history are essential if AOF is suspected. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is the best diagnostic modality for identifying a fistula or the presence of air in this area (Figure 1) [7-9]. Moreover, if neurological symptoms occur, CT and/or MRI scans of the brain are necessary to rule out the presence of septic or gas emboli, as was the case in our patient (Figures 2-3). If AOF is suspected, procedures such as gastroscopy and transoesophageal ultrasound should be avoided at all costs, as the air insufflate into the oesophagus during the procedure may lead to massive air embolism, resulting in stroke or death [13].

Urgent surgical repair is the cornerstone of treatment and has demonstrated the best outcomes [14]. Endoprostheses must be employed in cases of oesophageal perforation with no evidence of fistula, as a prophylactic treatment for AOF, or as a temporary bridge to surgery as it has already been stated that stents are not effective in avoiding embolism when there’s a real fistula and therefore cannot be considered a permanent therapy [15]. Protective measures such as reducing energy during thermo-ablation, the preventive use of high-dose proton pump inhibitors, oesophageal temperature monitoring, and irrigated ablation catheters have improved the incidence of AOF in some studies, but given this rare entity, identifying risk and protective factors is tricky and there is currently no consensus on these techniques [16].

Conclusion

Atrio-oesophageal fistula is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. A thorough anamnesis and a raised index of suspicion are necessary to establish a rapid diagnosis. Therapeutic management is challenging, and surgery appears to be the best strategy. Isolated oesophageal stenting is associated with a higher mortality rate.

Acknowledgment: No Acknowledgments

Disclosure and Conflict Of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent Statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) to publish any potentially identifiable images or data in this article.

Data Availability Statement: The data used and analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Bizhanov KA, Аbzaliyev KB, Baimbetov AK, Sarsenbayeva AB, Lyan E. (2023) Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical complications (literature review). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 34:153165.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, et al. (2021) ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 42:373–498.

- Poole JE, Bahnson TD, Monahan KH, Johnson G, Rostani H, et al., (2020) CABANA Investigators and ECG Rhythm Core Lab. Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation After Catheter Ablation or Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy in the CABANA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 75:3105–18.

- Hojgaard K, Raaschou-Nielsen T. (1970) Oesophago-cardiac fistula. A fistula between heart and oesophagus as causative agent in the development of embolic meningo-encephalitis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl 212:114.

- Gandjbakhch E, Mandel F, Dagher Y, hidden-Lucet F, Rollin A. (2020) Maury Pl. Incidence, epidemiology, diagnosis and prognosis of atriooesophageal fistula following percutaneous catheter ablation: a French nationwide survey. Europace. 23:557–64.

- Yousuf T, Keshmiri H, Bulwa Z, Kramer J, Arshad HMS, et al. (2016) Management of atrio-esophageal fistula following left atrial ablation. Cardiol Res 7:36–45.

- Jehaludi A, Heist EK, Giveans MR, Anand R. (2018) Retrospective review of 65 atrioesophageal fistulas post atrial fibrillation ablation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 18:100–7.

- Qumseya BJ, Kusumoto F, Wolfsen H. (2012) Esophageal injury following left atrial ablation. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 8:414–6.

- Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Santinelli V. (2013) Atrio-esophageal fistula after AF ablation: pathophysiology, prevention & treatment. J Atr Fibrillation. 6:860.

- Moiroux-Sahraoui A, Manceau G, Schoell T, Combes A, Bougle´ A, et al. (2021) Atrio-oesophageal fistula following atrial fibrillation ablation: how to manage this dreaded complication? Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 33:935–40.

- Moss CE, Fernandez-Caballero S, Walker D. (2015) Atrio-oesophageal fistula after transcatheter radiofrequency ablation. BMJ Case Rep. 2015:bcr2014204998.

- Kapur S, Barbhaiya C, Deneke T, Michaud GF. (2017) Esophageal injury and atrioesophageal fistula caused by ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circulation 136:1247–55.

- Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. (2012) 2012 HRS/EHRA/ ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the heart rhythm Society (HRS) Task force on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. developed in partnership with the European heart rhythm association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of cardiology (ESC) and. Europace. 14:528–606.

- Nair GM, Nery PB, Redpath CJ, Lam B, Birnie DH. (2014) Atrioesophageal fistula in the era of atrial fibrillation ablation: a review. Can J Cardiol. 30:388–95.

- Yousuf T, Keshmiri H, Bulwa Z, Kramer J, Sharjeel Arshad HM, et al. 16. Ellis CR, Streur M, Scharf AW, Nesbitt JC. (2012) Successful treatment (2016) Management of atrio-esophageal fistula following left atrial of esophageal perforation following atrial fibrillation ablation with a fully ablation. Cardiol Res.7:36–45. covered esophageal stent: prevention of atrial-esophageal fistula. J Innov Cardiac Rhythm Manage. 3:874–8.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.