Understanding Shoulder Kinematics During the Season: A Functional Analysis of Elite Female Volleyball Athletes

by Mantovani M1*, Cencini S2, Antonini G2, Varini A1, Sciascia A3, R Garofalo4

1NCS lab srl, Modena, Italy

2Savino del Bene volley Scandicci, Florence, Italy

3Lexington Clinic, Lexington, USA

4F. Miulli Hospital, Lum University, Italy

*Corresponding author: Matteo Mantovani, NCS lab Via Pola esterna 4-13, 41012, Carpi, Modena, Italy

Received Date: 02 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 12 Janaury 2026

Published Date: 15 January 2026

Citation: Mantovani M, Cencini S, Antonini G, Varini A, Sciascia A, et al. (2026) Understanding Shoulder Kinematics During the Season: A Functional Analysis of Elite Female Volleyball Athletes. J Orthop Res Ther 11: 1414. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-8241.001414

Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate and assess the three-dimensional humero-scapulo-thoracic kinematics using wearable technology in a group of professional female volleyball players along the season. Methods: The Showmotion three-dimensional kinematic tracking system is a motion analysis system that uses wireless, wearable inertial-magnetic sensors to assess the three-dimensional kinematics of the shoulder girdle. The system was used to measure the scapular angular motions in three planes (upward/downward rotation, internal/external rotation and anterior/posterior tilt) during two shoulder full-range movements (flexion/extension and abduction/ abduction) in both shoulders of 39 female volleyball professional players, mean age: 28.5 ±6.1 years). The measurement campaign involved 39 subjects, of whom 14 were evaluated throughout the season. Results: The study aggregated data from all participants (39 elite female players) and utilized a segmentation algorithm to analyze individual sessions. For each DOF, mean and standard deviation calculations were performed at one-degree increments, establishing confidence bands compared against normative literature. The graphical representation showed distinct differences between the professional volleyball players and the normal population. Key findings included a temporal comparison of bands at two time-points during the season, identifying significant differences in scapular tilt by season’s end (p =0.024 and p = 0.043, respectively for flexion and abduction). Additionally, static protraction angles were measured, showing a significant increase on the dominant side at different time points (p < 0.001). Conclusion: Kinematic evaluation offers a valuable method for monitoring upper limb function throughout the season, easily integrating into team routines. This dynamic assessment enables early detection of dysfunction and allows for precise tracking of parameters such as coordination, proprioception, and scapulohumeral rhythm. In this group, season load resulted in reduced tilting at the onset of flexion and abduction, with a general trend towards tilt inversion (anterior tilt in the overhead position). Additionally, a significant increase in the protraction angle at rest was observed. Level of evidence: Prospective observational, Level II

Keywords: Scapula; Kinematics; Volleyball; Scapulohumeral rhythm

Highlights

A quantitative functional evaluation is a useful tool to track an athlete in season The season load can be evidenced by the method and drift from normal can be addressed at an early stage

Introduction

The shoulder joint is a complex and highly mobile structure that plays a critical role in the performance of overhead athletes, particularly professional volleyball players, where powerful and repetitive movements are essential [24]. The integrity of the shoulder directly affects key performance metrics, including serving velocity and spiking accuracy, as well as injury prevention [8]. Volleyball, requires physical activities such as jumping, landing, and rapid movements, which can place significant stress on the musculoskeletal system and increase the risk of injuries [7]. Elite volleyball players can execute between 30,000 and 40,000 spiking movements annually, resulting in substantial cumulative stress on the shoulder, underscoring the importance of robust shoulder function for sustaining athletic careers [14].

The overhead throwing motion, intrinsic to volleyball, imposes considerable demands on the entire shoulder joint complex. This motion requires an optimal balance of flexibility, strength, and neuromuscular control to maintain dynamic functional stability [34].

The scapula acts as a vital link within the upper body kinetic chain, facilitating the transmission of forces generated from the lower body to the arm and hand, ultimately influencing the speed and accuracy of ball release [34]. Given the high levels of force generated and absorbed during volleyball, the risk of injury is significant, making shoulder integrity crucial for both performance optimization and injury prevention [5]. A comprehensive understanding of the biomechanical stresses experienced by the shoulder during volleyball-specific movements is essential for developing effective training and injury prevention strategies.

Scapulohumeral rhythm refers to the coordinated movement between the scapula and the humerus during arm elevation, optimizing range of motion and minimizing stress on the glenohumeral joint. The scapula’s movements, including upward/ downward rotation, internal/external rotation, and anterior/ posterior tilting, are orchestrated by a complex interplay of muscles, each contributing uniquely to the overall function [36]. Proper shoulder function relies on the synchronization of multiple body parts to maximize force generation, minimize joint load, and efficiently transfer force to distal segments, forming a kinetic chain [36]. The normal muscle activation pattern during scapulothoracic motion involves a precise sequence and magnitude of muscle contractions to achieve desired movements. The trapezius muscle, composed of upper, middle, and lower fibers, plays a crucial role in scapular kinematics. The transverse orientation of the upper and middle fibers of trapezius precludes any action as elevators of the scapula as commonly depicted. Rather, the action of these fibers is to draw the scapula and clavicle backwards or to raise the scapula by rotating the clavicle about the sternoclavicular joint [37]. The serratus anterior muscle pulls the scapula forward around the thorax, allowing for the arm’s anteversion and protraction. Also, the serratus anterior inferior is responsible for the anterolateral motion of the scapula, which allows for arm elevation. When the shoulder girdle is fixed, all three parts of the serratus anterior muscle work together to lift the ribs, assisting with respiration. Furthermore, the serratus anterior acts with the upper and lower fibers of the trapezius muscle to sustain upward rotation of the scapula, which allows for overhead lifting [38].

Repetitive microtraumatic stresses can lead to adaptations in shoulder range of motion, strength imbalances, and altered scapular kinematics, all of which may predispose athletes to injury [20]. The capsuloligamentous complex in the overhead athletes could be stretched with the time because of repetitive gesture, and the dynamic stabilizers are very important to prevent injuries of the gleno-humeral joint. With the onset of fatigue, the stabilizing structures of the shoulder, including the rotator cuff musculature, may become inadequate in preventing excessive joint translation, thereby elevating the risk of injury. To the best of our knowledge, the influence of the aforementioned factors has not been quantified through kinematic evaluation by many authors, and limited research has been conducted to describe the adaptations in terms of kinematic variables. In previous research on scapular kinematics, the impact of fatigue on this kinematics was evaluated. The authors discovered that fatigue in the intra- and extra-rotators of the upper limb altered the scapulohumeral rhythm and the range of motion in movements outside the scapular plane. Conversely, movements occurring near the scapular plane were less susceptible to alterations caused by fatigue [39].The purpose of this study was to make an objective kinematic evaluation of the shoulder complex. A cohort of 39 professional female volleyball players underwent kinematic evaluation to determine how the scapulohumeral rhythm (SHR) in female professional volleyball players differs from that measured in a normal population.

The hypothesis of the study is that sport-specific adaptations can result in statistically significant differences in shoulder kinematics. Additionally, muscular fatigue was supposed as a further influencing factor that may alter these specific movement patterns.

Materials and Methods

Instrumentation

The Showmotion three-dimensional Kinematic Tracking System (NCS Lab, Carpi, Italy) is a portable tool designed to employ motion tracking technology for monitoring shoulder movement patterns. The adopted set up consists of five wireless inertial measurement units (MIMUs) (Figure 1). Each MIMU provides both raw sensor data, which includes inputs from accelerometers, magnetometers, and gyroscopes, as well as an orientation matrix that delineates the orientation of the local System of Reference (SoR) in relation to a fixed SoR. Data from each MIMU are sampled and transmitted wirelessly to a laptop equipped with proprietary software that processes the data providing a biomechanical reconstruction immediately readable in the clinics.

Figure 1: The adopted measuring protocol is visible in the photo. Two sensors are on each shoulder, two on the humerus and 1 (not visible) on the thorax.

To commence the assessment, sensors are positioned on the standing participant in accordance with a standardized protocol, as previously outlined in other studies [4,12,13,18,23]. Placement points include one sensor at the manubrium sterni, two aligned with the scapular spine (inferior to the spine), and two on the lateral aspect of each humerus below the deltoid tuberosity.

Anatomical coordinate systems are established by obtaining static reference measurements with the subject standing upright, ensuring that the humerus is aligned alongside the body. Subsequently, the subject is instructed to adopt a standing resting position with arms at their sides and thumbs facing upward. During this calibration phase, the static position of the scapula is measured and recorded.

The participant is then directed to flex (or abduct) the shoulder to its maximum attainable elevation before returning to the resting position. Following this initial measurement, a series of abduction movements in the frontal plane is performed. This movement sequence is repeated consecutively seven times to account for variability during repetitions and to evaluate consistency and potential drift (pace was set by the operator).

The dynamic visualization of scapular angular kinematics (SAK) is presented in three angle-angle plots corresponding to each plane of humeral motion (flexion or abduction). These plots display the three scapulothoracic angular motions (internal-external rotation, upward-downward, tilt anterior/posterior) against humerothoracic elevation or abduction. A single measurement session, encompassing the entire process from sensor placement to the assessment of humero-scapulo-thoracic kinematics in three planes during flexion/extension (FL-EX) and abduction/adduction (AB-AD) movements, can be conducted by a trained operator in less than five minutes.

Subjects

A cohort of 39 professional female volleyball players underwent kinematic evaluation. None of the players had a history of previous shoulder surgery, and no participant reported experiencing shoulder pain in the six months preceding the measurements. All participants were regularly engaged in professional-level training and competition, following a consistent routine. A subgroup of players was longitudinally assessed at two distinct points during the season: at the beginning and subsequently towards the end. Before being measured, each participant underwent a practice session to familiarize themselves with the experimental procedure. All athletes were in optimal physical condition, with no reported symptoms that would impede their participation in the sport. Every measurement was taken in the morning in a resting condition and at least 48 hours from the latest game. Every measured athlete has a minimum of 4 years of experience in a professional team. The average age of the players was 28.5±6.1 years.

For the measurement of SAK, each movement, encompassing FLEX and AB–AD, was divided into upward and downward phases, spanning from 0° to 120°. We specifically analyzed the SAK for shoulder flexion and abduction within this range to minimize data dispersion at higher humeral elevations, as previously documented [23]. Each curve was resampled to 241 equally spaced points spanning from 0° to 120°.

Statistical analysis

Python 3.11.3 was used to perform statistical data analysis. The normality of the data was assessed using the Lilliefors test, which confirmed that the distribution was normal.

The kinematic evaluation encompassed: (1) the total range of scapular motion; (2) the consistency of movement, assessed as the dispersion across various repetitions; (3) the overlap between the elevation and depression phases of arm movement, noting that in a healthy individual, these lines should coincide in the graph, and any deviation may indicate microinstability (the curve in each plane represents the recruitment sequence utilized to perform the movement); (4) a comparison of the average curve shape with normative data to identify any deviations.

The sample size was calculated to achieve a statistical power (beta) of 0.8 for the analysis of range of motion (ROM) data, with a significance level (alpha) set at 0.05. The minimum clinically relevant difference was defined as one standard deviation, based on findings from previous studies [4,18]. This calculation yielded a minimum required sample size of 11 subjects. Comparisons across various intervals of the range of motion were conducted using the t-test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis also involved a temporal comparison of the bands at two distinct time points (Table 1). the beginning and the end of the season. After extracting the values for each subject at 30°, 60°, 90°, and 120° of elevation for both anterior flexion and abduction, we calculated the average and standard deviation for each degree of freedom at these intervals.

| T0 | T1 |

Abd |

| |

Abd | ||

Abd | ||

Flex | ||

Flex | ||

Flex |

Table 1: Kinematic evaluation and data aggregation at two subsequent time steps in flexion and abduction (T0 = beginning of the season; T1 = end of the season). (blue line = average from the population, Orange area = CI 95%; black line = average normal, green area = CI 95%)

Results

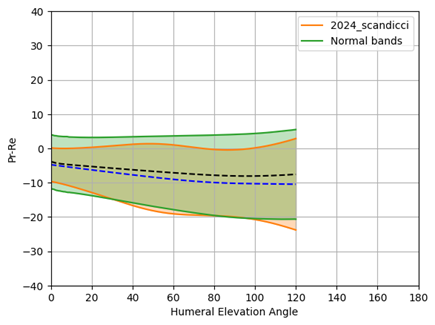

The data from all participants were aggregated for analysis. A specifically designed segmentation algorithm was employed to analyze individual sessions. For each degree of freedom, the data from all subjects were compiled, and the mean and standard deviation were calculated at every one-degree increment, establishing confidence bands for each exercise and rotational degree of freedom. (Table 2) provides a comparison of these averages and confidence bands against the normative data reported in the literature [4,12,13,18,23]. In the graphical representation, green areas denote the normality bands as defined in previous studies, the black line indicates the group average, the orange area instead illustrates the dispersion within this group (professional volleyball players), and the blue lines represent the average values

|

|

Abduction |

Flexion |

|

Pr-Re |

|

|

|

Up-Down |

|

|

|

Tilt |

|

|

Table 2: Data aggregation from 39 pro players (blue line = average from the population, Orange area = CI 95%) vs normal population (black line = average normal, green area = CI 95%)

Differences between the data from this group of professional volleyball players and a normal population are immediately apparent. Key variances includeDifferent use of tilt (less active and with the tendency to invert its value, anterior tilt).

- Increase in the scapulo-thoracic contribution in upward (in the overhead position)

- Increased protraction and reduced retraction (increased imbalance between scapular intra rotators and extra)

A t-test was performed to compare the kinematics at these discrete points across the two time-points. (Table 3) details the aforementioned values, with green cells highlighting the degrees of freedom and corresponding range of motion where statistically significant differences were observed. Notably, the only significant difference was found in scapular tilt, which demonstrated a reduced ability to posteriorly tilt by the end of the season. The values are respectively for flexion and abduction: 2.5°±2.3° (p<0.001) at 30° of flexion, 5.3°±2.9° (p=0.043) at 30° of abduction, 10.2°±3.8° (p=0.034) at 60° of abduction. Moreover, static protraction angles at rest were measured for both the dominant and contralateral sides.

|

First session (September 2024) |

S |

econd session (March 2025) |

|||||||

|

L = left, R = right |

Angle (°) |

30° |

60° |

90° |

120° |

30° |

60° |

90° |

120° |

|

L Flex Pr-Re |

avg |

4.6 |

8.6 |

8.8 |

4.2 |

2.8 |

5.2 |

5.7 |

3.9 |

|

std |

7.3 |

8.1 |

8.5 |

8.6 |

3.7 |

4 |

4.4 |

5.6 |

|

|

t-test |

0.284 |

0.057 |

0.098 |

0.85 |

|||||

|

L Flex Up-Down |

avg |

2.7 |

9.1 |

18.6 |

26.6 |

3.4 |

9.8 |

18.6 |

26.3 |

|

std |

3.2 |

4.1 |

4.8 |

5.5 |

2.5 |

3 |

3.7 |

4.4 |

|

|

t-test |

0.403 |

0.512 |

0.99 |

0.818 |

|||||

|

L Flex Tilt |

avg |

2.7 |

5.5 |

5.4 |

6.1 |

1.3 |

3.5 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

|

std |

3.1 |

3.7 |

4.7 |

5.5 |

1.3 |

3.6 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

|

|

t-test |

0.14 |

0.237 |

0.203 |

0.135 |

|||||

|

R Flex Pr-Re |

avg |

5.5 |

7.7 |

8.7 |

6.9 |

3.7 |

7.8 |

9.2 |

7 |

|

std |

5.7 |

6.2 |

6.5 |

6.9 |

3.1 |

5.2 |

6.6 |

8.8 |

|

|

t-test |

0.291 |

0.902 |

0.987 |

0.874 |

|||||

|

R Flex Up-Down |

avg |

3.9 |

11.1 |

21.6 |

31.5 |

3.6 |

10.1 |

19.9 |

28.2 |

|

std |

3.4 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

2.8 |

4.5 |

5.8 |

6 |

|

|

t-test |

0.727 |

0.452 |

0.294 |

0.068 |

|||||

|

R Flex Tilt |

avg |

2.6 |

3.9 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

1 |

-1.1 |

-2.4 |

|

std |

2.3 |

4.3 |

8.5 |

10 |

2 |

3.1 |

4.7 |

6.1 |

|

|

t-test |

0.024 |

0.062 |

0.217 |

0.135 |

|||||

|

First session |

Second session |

||||||||

|

Val_30 |

Val_60 |

Val_90 |

Val_120 |

Val_30 |

Val_60 |

Val_90 |

Val_120 |

||

|

L Abd Pr-Re |

avg |

-5.3 |

-7.2 |

-9.8 |

-11.7 |

-5 |

-6.3 |

-9.1 |

-10.4 |

|

std |

5.5 |

7 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

3.4 |

4.5 |

6.4 |

7.6 |

|

|

t-test |

0.829 |

0.662 |

0.752 |

0.571 |

|||||

|

L Abd Up-Down |

avg |

2.4 |

10.9 |

19.1 |

25.7 |

1.8 |

10.7 |

19.3 |

25.6 |

|

std |

2.2 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

3.5 |

2.3 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

5.1 |

|

|

t-test |

0.159 |

0.843 |

0.854 |

0.937 |

|||||

|

L Abd Tilt |

avg |

5.5 |

11.1 |

14 |

14.9 |

4.4 |

9.1 |

11.7 |

12.1 |

|

std |

2.2 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

3.8 |

3.2 |

4.5 |

5.2 |

6.3 |

|

|

t-test |

0.152 |

0.189 |

0.274 |

0.274 |

|||||

|

R Abd Pr-Re |

avg |

-7 |

-9.1 |

-10.2 |

-10.5 |

-7.7 |

-11.2 |

-11.5 |

-11.3 |

|

std |

4.1 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

7 |

4.9 |

6.2 |

6.6 |

8.2 |

|

|

t-test |

0.554 |

0.211 |

0.463 |

0.703 |

|||||

|

R Abd Up-Down |

avg |

2.3 |

11.1 |

21.3 |

31 |

1.1 |

10.4 |

20.6 |

29.1 |

|

std |

2.4 |

2.7 |

3.2 |

4.2 |

2.5 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

3.3 |

|

|

t-test |

0.165 |

0.478 |

0.437 |

0.185 |

|||||

|

R Abd Tilt |

avg |

5.3 |

10.2 |

12.7 |

12.9 |

4.2 |

7.8 |

10 |

10 |

|

std |

2.9 |

3.8 |

5.7 |

9.1 |

2.5 |

3.6 |

4.7 |

6.8 |

|

|

t-test |

0.043 |

0.034 |

0.133 |

0.299 |

|||||

Table 3: Comparison of the rotational degrees of freedom at discrete points across two different time points, with statistically significant values highlighted in green.(R=right; L= left; ABD = abduction; FLEX = anterior flexion; PR-RE = scapula protraction/retraction or internal/external; UP-DOWN = scapula upward/downward rotation; TILT = scapula tilt). The unit of measurement for the reported values is degree (°).

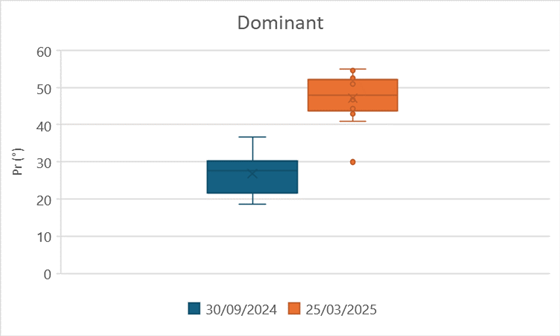

A t-test was conducted to compare protraction angles between the two sides at different time points, revealing a statistically significant increase in the protraction angle on the dominant side at the follow-up measurement p<0.001 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Scapular protraction angles on the dominant sides at two different time points. The values show a statistically significant difference.

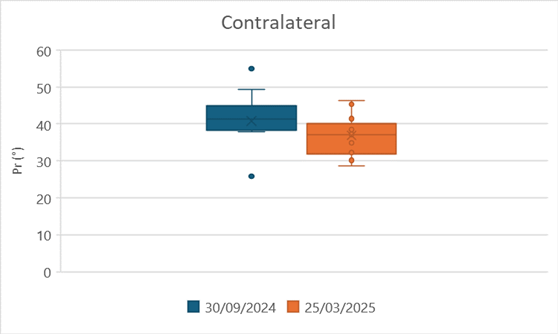

Non statistically significant difference was found on the contralateral, p=0.196 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Scapular protraction angles on the contralateral sides at two different time points. The values don’t show a statistically significant difference.

Discussion

The results of this study illustrate the adaptation patterns observed in a group of female professional volleyball players. Notably, the most significant differences were evident during flexion movements, where excessive internal rotation (protraction) and upward rotation were pronounced. These changes are attributed to an increased imbalance between the internal and external rotators, as well as a heightened contribution of the scapula during arm elevation.

Furthermore, the efficiency of scapular tilting is reduced, particularly in the overhead position. As the working load progressively increases throughout the season, there is also an observed elevation in the protraction (internal rotation) angle of the scapula at rest on the dominant side by the end of the season. This combination of increased protraction and reduced efficiency in scapular tilt may heighten the risk of injury.

Volleyball, characterized by repetitive overhead movements such as serving, spiking, and blocking, places substantial demands on the shoulder joint, predisposing athletes to a heightened risk of injury. The overhead-throwing athlete, a category encompassing volleyball players, presents a unique challenge in sports medicine due to the repetitive stresses imposed on the shoulder joint complex [21]. These stresses can lead to affecting performance or to different injuries, and potentially leading to long-term complications [22].

A foundational understanding of the biomechanics involved in volleyball-specific actions like serving and spiking is crucial for devising effective training and rehabilitation strategies, acknowledging the significant unilateral strain placed on the dominant shoulder [8]. Understanding the role of weightlifting in volleyball is paramount, as it serves as a primary means to enhance performance-related attributes and, concurrently, diminish the likelihood of injuries [5]. It is also important to understand the effects of weightlifting on both static posture and kinematics, particularly in determining whether it promotes an imbalance of intra- and extrinsic forces. However, as demonstrated in the current paper, it is equally important to monitor potential deviations an athlete may experience throughout the season due to various factors, including imbalanced workload, fatigue, and progressive dysfunction associated with nonspecific pain.

As evidenced in this research, the SHR of this population of female professional players differs from normal and shows a specific adaptation pattern mainly related to an increase of scapular internal rotation, a reduction of tilt in the horizon position, and an increased contribution of the scapulo-thoracic joint in upward rotation. The incidence of shoulder injuries in volleyball is a significant concern, with these injuries frequently leading to lost playing time and potential long-term complications. While specific epidemiological data on shoulder injuries in high-level volleyball athletes may be limited, studies on overhead athletes in general, including baseball players, swimmers, and tennis players, provide valuable insights [27]. There is also a paucity of data from female professional volleyball. The most frequent types of shoulder injuries observed in volleyball athletes include rotator cuff tendinopathies, shoulder impingement syndrome, glenohumeral instability, and labral tears [2]. Nevertheless, we know from different studies how important is normal scapular biomechanics to obtain a correct gesture of the arm in space. Most authors agree that abnormality in the patterns of scapular movements (STAM) [40] could predispose to above mentioned shoulder injuries, particularly in overhead athletes.

This altered scapular motion can disrupt the normal biomechanics of the shoulder joint, leading to increased stress on the rotator cuff tendons, labrum, and other structures. The evaluation protocol adopted in this study, helps in describing the SD and provides an objective and formal approach to its evaluation. In volleyball, scapular dyskinesis can arise from muscle imbalances, such as weakness of the serratus anterior or lower trapezius muscles, or from altered neuromuscular control. Exercises targeting scapular stabilization, including scapular retractions, protractions, upward rotations, and downward rotations, are essential for restoring normal scapular mechanics and preventing shoulder injuries. More recently, new devices have been introduced that are able to condition the scapular kinematic to a more normal pattern by using the concept of the motion-activated stimulation [35].

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the relatively small number of subjects monitored throughout the season. A larger cohort will be included in the continuation of this research, and additional measurements will be incorporated, such as intra- and external rotation of the humerus.

Conclusion

The shoulder of a high-performing professional volleyball player displays an adaptation that differentiates from a “normal” shoulder. The most significant differences consist in a reduced dispersion (indicating a better control) with the exception of the scapular tilt in overhead position. Additionally, the season load in this group reflected into a less active tilt since the beginning of the flexion and abduction and the general tendency to a tilt inversion (posterior tilt in the overhead position). The kinematic evaluation can be a valuable tool for tracking upper limb function during the season and be easily implemented into the team routine. The dynamic evaluation permits to assess the dysfunction at an early stage and it further permits to track and objectify parameters such as coordination, proprioception and scapula humeral rhythm that could help to retrain muscle better to prevent shoulder injuries.

References

- Bartlett R, Robins M (2008) Biomechanics of throwing.

- Brandsema CJ, Mehrab M, Mathijssen NMC (2022) Most Common Injuries in Crossfit Training: A Systematic Review [Review of Most Common Injuries in Crossfit Training: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Sports and Exercise Medicine 8(4).

- Hemecourt PA, Luke A (2012) Sport-specific biomechanics of spinal injuries in aesthetic athletes (dancers, gymnasts, and figure skaters). Clinics in Sports Medicine 31(3): 397.

- Galasso O, Mercurio M, Mancuso C, De Gregorio D, Mantovani M, et al. (2024) Kinematic stabilization after the Latarjet procedure: beyond the triple blocking effect. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 33(10): e547-e558.

- Holmberg PM (2013) Weightlifting to improve volleyball performance. Strength and Conditioning Journal 35(2): 79.

- Hurley JA, Anderson TE, Dear W, Andrish JT, Bergfeld J, et al. (1992) Posterior shoulder instability. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 20(4): 396.

- Keoliya A, Ramteke SU, Boob MA, Somaiya KJ (2024) Enhancing volleyball athlete performance: A comprehensive review of training interventions and their impact on agility, explosive power, and strength. Cureus 16(1): e53273.

- Khan AM, Guillet MA, Fanton G (2001) Volleyball: Rehabilitation and training tips. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 9(2): 137.

- Kibler WB, McMullen J, Uhl TL (2001) Shoulder Rehabilitation Strategies, Guidelines, and Practice. Orthopedic Clinics of North America 32(3): 527.

- Lidor R Ziv G (2010) Physical and physiological attributes of female volleyball players-a review. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 24(7): 1963-73.

- Ludewig PM, Braman JP (2010) Shoulder Impingement: Biomechanical Considerations in Rehabilitation. Manual Therapy 16(1): 33.

- Manceron A, Jawa A, Mantovani M, Werthel JD (2025) Involvement of the scapulothoracic articulation after well-functioning reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 34(9): S2258-2268.

- Mantovani M, Sciascia A, Varini A, Muraccini M, Nardini F, et al. Accuracy of measuring scapular position and motion with a novel motion capture system. JSES Rev Rep Tech 3(3): 303-311.

- Martinez D (2017) Consideration for power and capacity in volleyball vertical jump performance. Strength and Conditioning Journal 39(4): 36.

- Millett PJ, Gobezie R, Boykin RE (2008) Shoulder Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Management 78(5): 605.

- Mohammed K, Cadogan A, Robinson D, Roche J (2015) The shoulder in the collision athlete Orthopaedics and Trauma 29(3).

- Pepe M, Rodosky MW (2001) Nonoperative Treatment of Common Shoulder Injuries in Athletes. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 9(1): 96.

- Reina M, Fiumana G, Mantovani M, Antonio DL, Porcellini G (2023) Scapulohumeral rhythm in shoulders with reverse shoulder arthroplasty measured with a new portable three-dimensional scapular kinematics assessment system. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 32(4): 729-737.

- Reinold M, Gill T (2009) The overhead-throwing athlete: Classification of injury patterns. Sports Medicine 2(1): 39-50.

- Reinold MM, Gill TJ (2009) Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder in Overhead-Throwing Athletes, Part 1. Sports Health 2(1): 39.

- Reinold MM, Gill TJ, Wilk KE, Andrews JR (2010) Current Concepts in the Evaluation and Treatment of the Shoulder in Overhead Throwing Athletes, Part 2: Injury Prevention and Treatment. Sports Health 2(2): 101.

- Reinold M, Wilk K, Fleisig G, Andrews J (2010) Biomechanics and injury risk assessment in the overhead-throwing athlete. American Journal of Sports Medicine.

- Ruiz Ibán MA, Gonzalez AP, Muraccini M, Asenjo Gismero CA, Varini A, (2020) Evaluation of a novel portable three-dimensional scapular kinematics assessment system with inter and intraobserver reproducibility and normative data for healthy adults. J Exp Orthop 7(1): 31.

- Schenkman M, Cartaya VR (1987) Kinesiology of the Shoulder Complex. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 8(9): 438.

- Schultz J (2004) Clinical Evaluation of the Shoulder. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America 15(2): 351.

- Seitz WH, Michaud EJ (2012) Rehabilitation After Shoulder Replacement: Be All You Can Be! Seminars in Arthroplasty JSES 23(2): 106.

- Summitt RJ, Cotton RA, Kays AC, Slaven EJ (2016) Shoulder Injuries in Individuals Who Participate in CrossFit Training. Sports Health 8(6): 541.

- Summitt R, Taber CB, Smith MD, Schoenfeld BJ (2016) Shoulder injuries in overhead athletes: Incidence, risk factors, and prevention. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine.

- Sung JH, Jung W, Wang J, Kim JH (2023) The Effects of Body Positions and Abduction Angles on Shoulder Muscle Activity Patterns during External Rotation Exercises. Healthcare 11(14): 1977.

- Szabo DA, Filep BA, Banceu C, Neagu N (2022) The Frequency of Injuries among CrossFit Athletes: A Systematic Review. Health Sports & Rehabilitation Medicine 23(3): 130.

- Szabo RM, Marder RA, McMahon PJ (2022) Shoulder impingement syndrome: Diagnosis and treatment. Sports Health.

- Weber AE, Kontaxis A, Brien SJO, Bedi A (2014) The Biomechanics of Throwing. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 22(2): 72.

- Welbeck AN, Amilo NR, Le DT, Killelea CM, Kirschn AN (2019) Examining the Link between Thoracic Rotation and Scapular Dyskinesis and Shoulder Pain amongst College Swimmers. Physical Therapy in Sport 40: 78-84.

- Wilk KE, Meister K, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR (2000) Biomechanics of the Overhead Throwing Motion. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 8(2): 124.

- Moroder P, Karpinski K, Akgün D, Danzinger V, Gerhardt C, et al. (2024) Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation-Enhanced Physical Therapist Intervention for Functional Posterior Shoulder Instability (Type B1): A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Physical Therapy 104(1): 145.

- Provencher CMT, Makani A, McNeil JW, Pomerantz ML, Golijanin P et al. (2014) The Role of the Scapula in Throwing Disorders Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 22(2): 80.

- Johnson G, Bogduk N, Nowitzke A (1994) House D Anatomy and actions of the trapezius muscle. Clin Biomech 9(1): 44-50.

- Lung K, Lucia KS, Lui F (2025) Anatomy, Thorax, Serratus Anterior Muscles. StatPearls.

- Zago M, Kawczyński A, Klich S, Pietraszewski B, Galli M et al. (2020) Fatigue-Induced Scapular Dyskinesis in Healthy Overhead Athletes. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8(1).

- Gedik CC, Eren İ, Demirhan M, Elhassan B (2024) A comprehensive review of scapulothoracic abnormal motion (STAM): evaluation, classification, and treatment strategies. In Acta orthopaedica et traumatologica turcica 58(4): 187-195.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.