Understanding Resiliency in NRMP Match Applicants Pursuing Orthopaedic Surgery Residency

by Sean McMillan1, ShelRamsey2, Brain Truong3, Manuel Pontes4, Charlie Yoo5, Efstratios Papadelis6, Elizabeth Ford7, Robert Garner8, William DiCiurcio9

1Virtua Health System, Rowan University, USA

2UPMC Central Pennsylvania Orthopedic Surgery Residency, USA

3Aultman Hospital - Orthopedic Surgery Residency, USA

4Rowan University, USA

5Resurgeons Orthopaedics, USA

6Grand Stand Medical Center, USA

7Alleghany Health Network, Sports Medicine Fellowship, USA

8Jefferson Health New Jersey Orthopedic Surgery Residency, USA

9Kansas City University Consortium – HCA, Orthopedic Surgery Residency, USA

*Corresponding author: Sean McMillan, Virtua Health System, Rowan University, 2103 Mount Holly Rd, Burlington NJ 08016, Tel: 609-747-9200, USA.

Received Date: 01 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 12 January, 2026

Published Date: 15 Janaury, 2026

Citation: McMillan S, Ramsey S, Truong B, Pontes M, Yoo C (2026) Understanding Resiliency in NRMP Match Applicants Pursuing Orthopaedic Surgery Residency. J Orthop Res Ther 11: 1413. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-8241.001413

Abstract

Objective: This prospective cohort study evaluated outcomes of osteopathic applicants’ self-perceived resiliency in the orthopedic surgery match. Design: Persons intending to apply to orthopedic surgery residency programs were surveyed before the 2024 Match to determine their degree of resiliency utilizing the Brief Resiliency Scale

(BRS). A follow-up survey after Match Day 2024 collected outcomes. The mean resiliency score from each Match outcome was analyzed using a t-test with significance of p < 0.05 level. Setting: A nationally distributed survey.

Participants: Study participants were drawn from medical students rotating at several orthopedic surgery programs and from members of the Student American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics (SAOAO), all intending to apply to orthopedic surgery in the 2024 application cycle. 124 applicants’ outcomes were established.

Results: Applicants who successfully matched into orthopedic surgery residency programs had a higher average BRS score of

4.28 compared to a mean BRS of 4.09 in participants who did not match into orthopedic surgery (p = 0.0473). Subgroup analysis revealed matched to orthopedic surgery had a higher BRS score than students who ultimately did not apply to orthopedic surgery (3.83; p = 0.038). Inversely, self-perception of high resilience (BRS = 4.5-5.0) was associated with higher rates of matching into orthopedic surgery (p = 0.040). Conclusions: Medical students who matched into orthopedic surgery training programs through the NRMP had higher levels of resiliency than students unmatched to orthopedic surgery. Higher levels of resiliency were associated with higher rates of matching into orthopedic surgery. These findings may provide another indicator for applicants to self-assess their suitability for the orthopedic surgery match. Further research includes assessment of resiliency in reapplicants and allopathic applicants.

Keywords: Resiliency, Residency, Orthopedic Surgery, Match, Medical Student

Introduction

Resiliency was identified by Zwack and Sweitzer as being a central element of physician well-being [1]. Resiliency is a psychometric property that captures a person’s ability to manage and adapt to stressors [2,3]. Physicians are regularly subject to challenges directly linked to their career, such as extensive working hours, increasing administrative duties, and the stress of providing optimal patient care [4]. Inherent personality traits such as optimism and ability to regulate emotions have been shown to make an individual resilient [5]. Additionally, one’s internal resiliency can also be modified or acquired via extrinsic factors to a degree, however in large part has been shown to remain static over time [6,7].

Challenges also exist for medical students applying into orthopedic training programs. Long work hours, travel to complete rotations at residency programs, a competitive field of applicants, and the emotional stress and strain of learning large amounts of information daily can factor into one’s level of resilience [8,9]. Overcoming these challenges may in part be due to a persons’ internal resilience level. In turn, this pre-match resiliency may play a role in future success as an orthopedic resident and attending physician. With the challenges applicants face matching into orthopedics, being able to recover from setbacks and adapt to difficulties may prove to be a significant character trait correlated with successfully matching.

To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between resiliency and outcomes of medical students applying to orthopedic surgery. We hypothesize that persons applying into orthopedic surgery residency training programs with higher degrees of resiliency will have higher match rates.

Methods

Participants

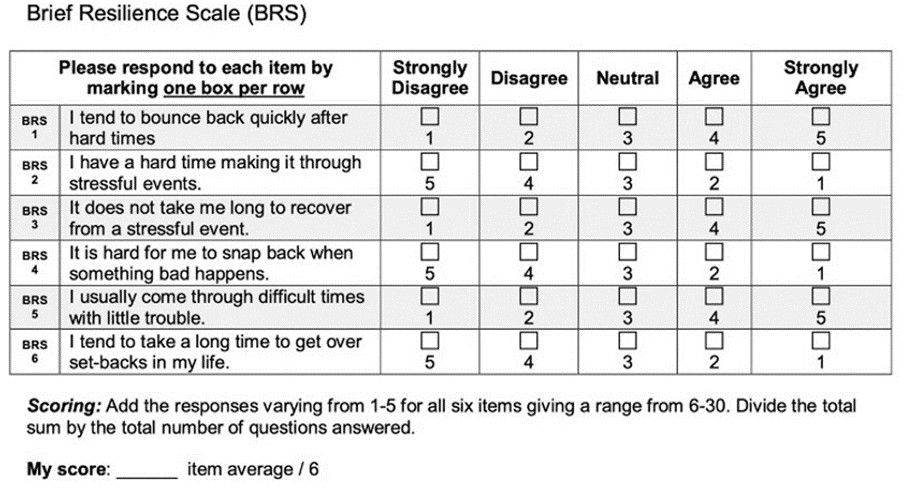

IRB approval for this cross-sectional study was obtained from the lead author’s internal Institutional Review Board (IRB). A Qualtrics survey consisting of the Brief Resiliency Scale (BRS), a six-question Likert scale that has been found to reliably assess resilience, was distributed to persons applying to orthopedic residency programs in the 2024 cycle (Figure 1) [10]. The survey (Figure 2) was distributed to students completing audition rotations at six orthopedic residency programs and via the Student American Osteopathic Academy of Orthopedics (SAOAO) to SAOAO Conference attendees and through social media. These outlets were chosen due to the target population of those applying to the National Residency Program Match (NRMP) in 2024 for orthopedic surgical training. Participants were included if they were (1) a fourth-year medical student and (2) applying to orthopedic surgery residency programs in the 2024 NRMP Match. Those that selected they did not meet inclusion criteria were contacted and included if they indicated they were reapplicants to the NRMP Match and were applying to orthopedic surgery in the 2024 Match. Exclusion criteria consisted of (1) not applying to orthopedic surgery residency training programs in the 2024 NRMP Match, (2) not fourth year medical students or reapplicants to the NRMP Match, (3) declined to fill out the questionnaire, (4) declined to provide contact information for post-Match follow-up, or (4) were unable to fill out the questionnaire. All participants acknowledged that their response was voluntary and that they would be contacted after the 2024 NRMP Match to ascertain their match status. No incentive was offered. All participants were made aware that they could voluntarily withdraw from the study at any time without any prejudice.

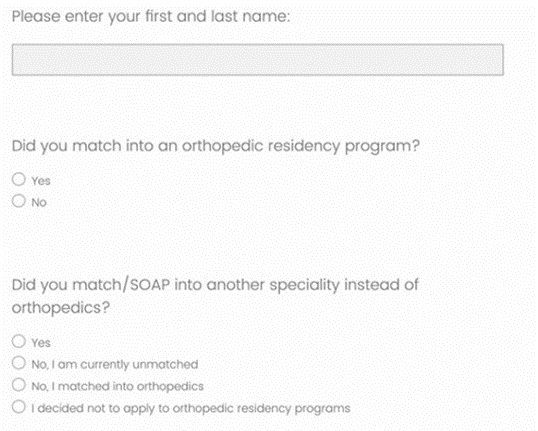

The project was divided into two separate phases. For the first phase, applicants were asked to complete the survey containing the BRS prior to March 15th, 2024 (Match Day). The first day the survey became available was July 15th, 2023. These individuals were then contacted again on March 17th, 2024, with a secondary survey to determine their match status (Figure 3).

Figure 1: The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) questionnaire, a Likert scale with 6 items that assesses the resiliency of participants.

Figure 2: Primary Survey Distributed to Orthopedic Surgery Residency Program Applicants that included participant consent, the BRS, information necessary to determine if participant met inclusion criteria, and information necessary for follow-up.

Figure 3: Secondary Survey Distributed After Match Day used to determine participants’ match status.

Additionally, public information sources available via the internet and social media were used to supplement Match outcomes information. Orthopedic residency programs that publicly released their incoming interns were assessed to verify if any persons listed were participants in the primary survey. For those that failed to respond to the follow-up survey, the participant name and “residency” was used in an internet search to seek if any residency program had announced their placement in their program.

Sampling bias was avoided in this study through distribution of the survey via multiple methods, allowing for collection from broad demographics. Non-response bias was reduced through follow-up with those that completed the primary survey via weekly emails with reminders to complete the secondary survey. A total of 5 weekly emails were sent to encourage responses.

Resiliency Classification

We utilized a categorical variable, Resiliency Levels. Respondents with a BRS score < 4 were classified as Low Resiliency, respondents with a BRS score between 4 and 4.49 inclusive were classified as Medium Resiliency and those whose BRS score was 4.5 or greater were classified as High Resiliency. The percentage of matched respondents within each category was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

JMP Pro software (version 17.1.0; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) and R (version 4.4.3; R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for data analyses. Two-way t-tests were used to evaluate whether respondents who matched had higher BRS score compared to all respondents who did not match to orthopedic surgery as well as to each subcategory of respondent not matched to orthopedic surgery. Chi-square test was used to determine whether respondents with Low Resiliency had lower match rates than respondents with Medium or High Resiliency [11,12]. The Cochran-Armitage test was performed to evaluate for a trend between higher Resiliency categorization and proportion of respondents who matched into orthopedic surgery. p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

In total, 124 match outcomes were established. In total, there were 70 matched applicants and 54 unmatched applicants (Table 1). Of the 54 unmatched applicants, 18 match outcomes were obtained from public information sources. Therefore, we were unable to determine whether these outcomes were the result of applicants participating in the SOAP, going unmatched in orthopedic surgery but matching into another specialty, going completely unmatched, or not applying to orthopedic surgery. There were 118 osteopathic participants and six allopathic participants. The seven respondents that noted their decision to not apply to orthopedic surgery programs were all associated with osteopathic medical schools.

Respondents who matched had higher resiliency scores than those who did not match (4.28 versus 4.09, p = 0.047 (Table 1). The BRS score of respondents who matched was higher than those who chose not to apply to orthopedic surgery (4.28 versus 3.83, p = 0.038) (Table 2). Respondents with High Resiliency had a significantly greater percentage of applicants that matched than respondents with Low Resiliency (56.0% versus 29.7%, p = 0.040) (Table 3). While not statistically significant, the percentage of respondents with Medium Resiliency that matched was also higher than respondents with Low Resiliency (46.8% versus 29.7%, p = 0.096). Lastly, there was a significant trend between increasingly higher resiliency category and the proportion of respondents that matched (p = 0.033).

|

Matched |

Did Not Match |

p |

|

|

Mean BRS Score (n) |

4.28 (54) |

4.09 (70) |

0.0473 |

Table 1: Difference in Mean BRS Scores (Matched versus Did Not Match). Note: n = number of respondents in group, p = probability (significance level).

Category | Mean BRS (n) | p |

Matched in Orthopedic Surgery | 4.28 (54) | |

SOAPed/matched into other specialty | 4.12 (35) | 0.306 |

Currently Unmatched | 4.09 (9) | 0.315 |

Decided not to apply to orthopedic surgery | 3.83 (7) | 0.038 |

Table 2: Mean BRS Score by Category (Matched versus Subgroups of Did Not Match). Note: n = number of respondents in group, p = probability (significance level).

Matched Percentage (n/N) | Matched Percentage Difference [95% CI] | p | |

Low Resiliency (0.00-3.99) | 29.7% (11/37) | ||

Medium Resiliency (4.00 – 4.49) | 46.8% (29/62) | 17.0% [-3.1, 35.1] | 0.096 |

High Resiliency (4.50-5.00) | 56.0% (14/25) | 26.3% [1.2, 48.7] | 0.04 |

Table 3: Percentage of Participants who Matched by Respondent’s Resiliency Level (Low Resiliency vs. Medium and High Resiliency). Note: n= number of matched respondents, N = total number of respondents with associated resiliency level, p = probability (significance level).

Discussion

We confirmed our hypothesis that persons who matched into orthopedic surgery would demonstrate a higher BRS score than those that did not match into orthopedic surgery. There are no prior studies in this field to compare outcomes with, though there is anticipation that the field of studying resilience will continue to expand and provide future data. Orthopedic residency programs may be aided by utilizing resiliency metrics to identify candidates that will be successful in residency training.

While the mean BRS score of candidates that matched successfully into orthopedic surgery and the mean BRS score of candidates that did not match successfully into orthopedic surgery both are within the “Medium Resiliency” category, their difference is still meaningful. The statistical significance between their difference highlights that orthopedic surgery candidates are not required possess the highest degree of resiliency to be successful at matching into orthopedic surgery, but instead benefit from being more resilient than the average candidate.

Orthopedic surgery continues to be one of the most competitive fields to match into [13] Applicants to orthopedic surgery residency programs face increasing pressure to apply broadly and complete visiting rotations to be competitive [8,14]. These hurdles may tease out applicants of higher levels of resiliency who have higher odds of successfully matching into orthopedics. We suspect that those students able to overcome these pressures excel in the overall facets that contribute to successfully matching, including both objective accomplishments on a candidate’s application as well as their subjective performance on audition rotations.

Conversely, applicants who decided not to apply to orthopedic surgery were found to have a lower BRS score. This may reflect self-evaluation during the audition period that the challenges of orthopedic surgery auditions and residency were not aligned with their level of resiliency. Consequently, these applicants may have chosen to pursue a better suited specialty.

During the application process, students have the option to apply to multiple specialties, often termed dual-applying, or participate in the SOAP if they receive no offers during the first round of the Match. In 2024, there was only one unfilled orthopedic surgery position, compared to Family Medicine, which had 241 unfilled positions and Surgery-Preliminary (PGY-1 only), which had 155 unfilled positions [15]. The difference in BRS scores between those that SOAPed or applied to multiple specialties was not statistically significant compared to those that did match to orthopedic surgery (p = 0.306). This implies that while resiliency may be an indicator for success in matching to orthopedic surgery, it is not in itself a causative factor.

Only three of the participants were reapplicants. While their mean resiliency score was of interest compared to first time applicants’, the small sample group underpowered our ability to determine statistical significance. A potential difference in BRS score in reapplicants may be explained by a more tenacious nature in electing to continue the pursuit of orthopedics despite having not matched initially. Future studies may include a comparison of scores between those that did not initially match in orthopedics and re-applied versus applicants that did not match and then pursued other specialties.

Limitations

A limitation to this study is sample size, which can be explained by maximum possible responses being limited by the number of persons that apply to orthopedic residency programs each year. In the NRMP Match of 2024, 256 osteopathic seniors applied to orthopedic residency programs [16]. Our study of 124 participants captures a bulk of the osteopathic applicants to orthopedic residency programs, as all but six study participants were osteopathically trained. Coordination with each historically osteopathic orthopedic residency program to administer the survey to their applicants may ensure more results. Expanding the study over several cycles would power our findings and allow us to determine resiliency trends over time. As our study concentrated on osteopathic applicants, further studies could also include a comparison of BRS scores between osteopathic and allopathic applicants.

Not all participants that completed the primary survey completed the secondary survey ascertaining their match status. This is perhaps explained by those that did not match in the NRMP 2024 Match understandably seeking privacy after receiving news of their status. Eighteen participants did not respond to the followup survey but were found by online search to have matched outside of orthopedic surgery. Because these participants did not respond to the secondary survey, their outcomes were not able to be categorized as “SOAPed/matched into other specialty” or “Decided Not to Apply to Orthopedic Surgery”. Had these outcomes been able to be further categorized, the mean BRS of these groups may have been affected to the extent that statistical significance could have been established.

While a validated instrument, the BRS score has not been widely studied in the medical education community. This is a limitation as the minimum difference between levels of resiliency to have other known effects in medical education is largely unknown. Future research into BRS scores of medical students as compared to persons not in medical school, BRS scores of medical students pursuing differing medical specialties, and BRS scores of medical students at different stages of medical school may be beneficial.

A potential limitation to this study, and utilization in the residency application process, is that applicants to orthopedic surgery residency programs may respond with a higher BRS score than what truly represents their resiliency level. This potential response bias may be due to conscious or unconscious desire to appear as a better applicant.

Conclusions

Significantly higher levels of resiliency were found amongst medical students who matched into orthopedic surgery training programs through the NRMP.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Zwack J, Schweitzer J (2013) If Every Fifth Physician Is Affected by Burnout, What About the Other Four? Resilience Strategies of Experienced Physicians. Academic Medicine 88(3): 382-389.

- Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J (2011) A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 9(1): 8.

- Drayer NJ, Wallace CS, Yu HH, Mansfield TD, Cummings DL, et al. (2020) High Resiliency Linked to Short-Term Patient Reported Outcomes and Return to Duty Following Arthroscopic Knee Surgery. Military Medicine 185(1-2): 112-116.

- McKinley N, Karayiannis PN, Convie L, Clarke M, Kirk SJ, Campbell WJ (2019) Resilience in medical doctors: a systematic review. Postgraduate Medical Journal 95(1121): 140-147.

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF (2004) Psychological Resilience and Positive Emotional Granularity: Examining the Benefits of Positive Emotions on Coping and Health. Journal of Personality 72(6): 1161-1190.

- Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R (2014) Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 5(1): 25338.

- Karaırmak Ö, Figley C (2017) Resiliency in the Face of Adversity: A Short Longitudinal Test of the Trait Hypothesis. The Journal of General Psychology 144(2):89-109.

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J (2016) The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ 16(1): 291.

- Light J, Gonzalez S, Franzetti M (2019) Unexplored Questions About Away Rotations – A Student’s Perspective. MedEdPublish 8:19.

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J (2008) The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 15(3):194-200.

- R Core Team (2023) R: A language and environment for statistical computing.

- Laud P (2025) ratesci: Confidence Intervals for Comparisons of Binomial or Poisson Rates.

- Nasser JS, Artino Jr AR, Kind T, Duan X, Mihalic AP, Chretien K. Matching into competitive surgical residencies: predictors of success. Medical Education Online 28(1): 2189558.

- Trikha R, Keswani A, Ishmael CR, Greig D, Kelley BV, Bernthal NM (2020) Current Trends in Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Applications and Match Rates. JBJS 102(6): e24.

- National Resident Matching Program (2024) Advance Data Tables: 2024 Main Residency Match.

- Holmstrom A (2018) National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). In: Patti MG, Fisichella PM, eds. The American Health Care System: A Practical Guide for Foreign Medical Graduates Who Want to Enter the System. Springer International Publishing 2018:21-31.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.