Treatment of a Traumatic Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis in a 10 Month Old Infant-Never Forget to Think About Child Abuse

by Katharina S Gather1-2*, Sebastien Hagmann1-3

1Clinic for Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, Center for Orthopedics, Trauma Surgery and Spinal Cord Injury, Heidelberg University Hospital, Schlierbacher Landstrasse 200a, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany

2Departement for Pediatric Orthopedics, University Hospital Mannheim, Theodor-Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, 68167 Mannheim, Germany

3German Joint Center Heidelberg, ATOS Clinic, Bismarckstrasse 9-15, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany

*Corresponding author: Katharina Susanne Gather, Clinic for Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, Center for Orthopedics, Trauma Surgery and Spinal Cord Injury, Heidelberg University Hospital, Schlierbacher Landstrasse 200a, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany

Received Date: 07 November 2024

Accepted Date: 12 November 2024

Published Date: 14 November 2024

Citation: Gather KS, Hagmann S (2024) Treatment of a Traumatic Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis in a 10 Month Old InfantNever Forget to Think About Child Abuse. Ann Case Report. 9: 2062. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102062

Abstract

A 10-month-old infant with a slipped capital femoral epiphysis presented to our outpatient clinic. The cause remained unclear. Despite the lack of blood supply as seen in MRI, surgical treatment was performed with open reduction and screw and K-wire osteosynthesis. A report of suspected child abuse was made to the Youth Welfare Office, which was confirmed in the long term. Despite the lack of blood supply to the femoral head on imaging and intraoperatively, there was good remodelling with coxa magna and mild dysplasia within the next 2.5 years.

Keywords: SCFE; Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis; Child Abuse.

Abbreviations: MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Introduction

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in infants is extremely rare and usually associated with severe trauma (citation). Except in the case of endocrine disorders, they occur in adolescence [1]. Few cases are described in the context of caesarean section often in association with difficult delivery and a twisting movement of the femur during breech deliveries [2,3]. Here we report a severe case in a 10-month-old infant as a consequence of domestic violence and its medical therapy.

Case Presentation

A mother with a 10-month-old baby presented to our Orthopaedic Trauma Emergency Department. She had not been able to put any weight on her right leg for two weeks and was very tearful. She had previously been able to walk a few steps. She had no memory of an accident or similar event. However, the mother of two children, whose brother is 20 months old, could not rule out the possibility of trauma, as the children were sometimes left unattended for short periods of time.

The girl was born spontaneously after an unremarkable pregnancy with a birth weight of 3700g. The obligatory ultrasound examination of the hips at the age of 4-6 weeks (U3 examination) was unremarkable.

The mother first went to the paediatrician. He treated her for an infection. At the second visit, however, he noticed a bump on the hip and arranged for her to see a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon. This led to the presentation at our clinic in August 2021. At the first presentation, the girl was in good general and nutritional condition. There was no evidence of infection, either local or systemic. The infant refused to bear weight on both legs. The range of motion of both hips for extension/flexion was 0-0-150 degrees. Abduction was asymmetric with 70 degrees on the right and 80 degrees on the left.

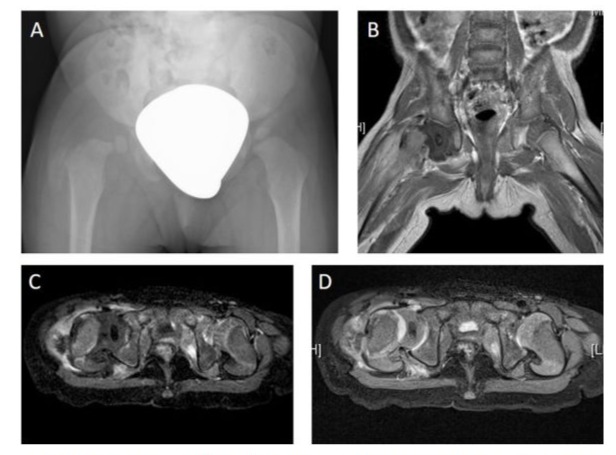

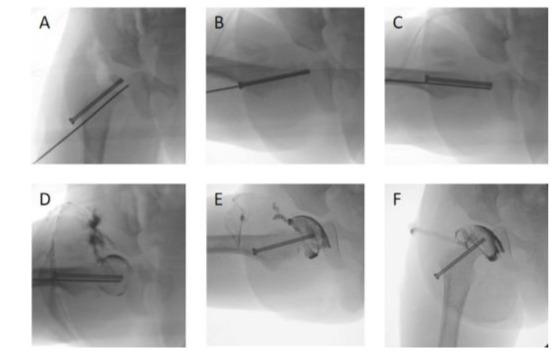

Radiographs (Figure 1) showed the slipped epiphysis of the greater trochanter and caput femoris. The subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Figure 1) showed a complete epiphysiolysis of the caput femoris with preserved contact to the acetabulum. There was no evidence of blood supply to the femoral head, with extensive oedema in the cartilaginous tissue and greatly reduced contrast uptake in the epiphysis and epiphyseal cartilage. Surgical management of the injury was undertaken one day after presentation to our emergency department and completion of the diagnostic work up. Initially, a closed reduction of the femoral head was attempted using various combinations of flexion, abduction and internal rotation maneuvers. This was unsuccessful and after 3 attempts an open reduction was performed. The incision was opened from the anterior superior iliac spine towards the groin. The joint capsule was opened in a crosswise manner and joint fluid was aspirated for microbiology. The femoral head was left in the socket and ossifications were noted and removed. An anatomical reduction was achieved with a Kirschner wire in the femoral head in the form of a joystick. After placing 2 threaded wires across the femoral neck, a 3.5mm cannulated screw was inserted through the central bone core (Figure 2).

The thread was shortened beforehand so that it would not come to rest in the epiphyseal groove. The femoral head was extremely soft and no blood came out of the head even after the joystick wire was removed. Arthrography was also used to confirm the reduction result and the correct implant position. After closure of the situs, a Spica cast was applied intraoperatively for 3 weeks in flexion, abduction and slight internal rotation on both sides with a small wound window on the right.

Immediately post-operatively, a forensic examination was initiated in the recovery room. This included a radiological examination of the skull and extremities. There was no evidence of previous or concomitant injuries. The Youth Welfare Office was also informed, and there was no indication of a problem with domestic care.

After 3 weeks, we switched to a foam splint in 40 degrees of abduction for night use.

The mother always attended the follow-up appointments, even though, according to the mother, they were repeatedly postponed due to colds. For this reason, the Kirschner wire was not removed until 2.5 months later. In the intraoperative arthrogram (Figure 2), the head was present and showed no mobility during movement. On outpatient follow-up, the patient presented with a non-displaced humeral shaft fracture, which was treated conservatively. We arranged for the patient to be admitted to the paediatric clinic for further injury assessment, including an MRI of the skull, and to rule out endocrinological or similar underlying conditions. A new report was made to the Youth Welfare Office, resulting in two-day appointments with the responsible paediatrician.

The screw was removed without complication after 6 months. Unfortunately, on the day of surgery, the patient presented with multiple haematomas around her eyes and armpit. She was again reported to the Youth Welfare Office.

In subsequent follow-ups, the mother told us that she had taken her children to a Youth Welfare Office-sponsored facility to get help with their care. In this case, the father turned out to be the cause of the injuries.

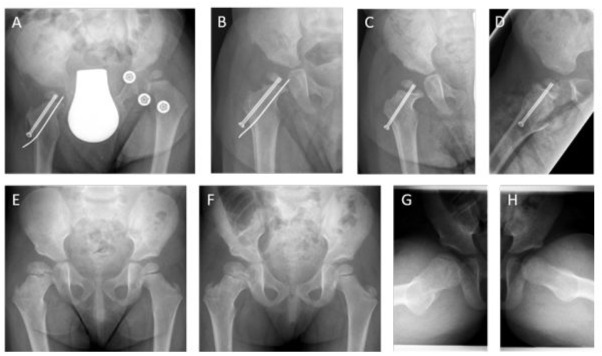

As far as the hip is concerned, fortunately the femoral head has recovered. Mobility is 0-0-120 degrees for extension/flexion of the hip and 50-0-50 degrees for internal/external rotation. There was a coxa magna and mild dysplasia of the acetabulum (Figure 3). However, the course of the disease was positive and no further intervention is planned at this time.

Figure 1: Initial imaging showing right-sided epiphysiolysis of the femoral head. A Pelvic view with right-sided tilted femoral head. B Coronary T1 sequence on contrast-enhanced MRI. The markedly reduced blood flow in the right proximal femoral epiphysis is clearly visible. C Transverse T1 sequence on contrast-enhanced MRI. Again, there is clearly reduced blood flow in the right proximal femoral epiphysis. D Transverse PD MRI image.

Figure 2: Intraoperative images of initial treatment (A-D) and K-wire removal (E-F). A-C Illustration of the implant position with a 3.5 partially threaded screw and a K-wire. A well reduced femoral head epiphysis is shown in 3 planes. D Arthrography to confirm the position of the implant in the femoral head and the reduction of the head in the acetabulum. E-F Arthrography after K-wire removal (after 2.5 month) to show the fixed femoral head epiphysis.

Figure 3: Postoperative course after initial treatment A 1-month postoperative B 2 months postoperative C-D 6 months postoperative ap and axial. E 1.5 years later F-H 2.5 years after surgery. Mild hip dysplasia with coxa magna on the right side. No coxa vara or premature closure of the growth-plate at present.

Discussion

Due to our knowledge, no such case of an infant has been described to date. Isolated cases have been reported in connection with osseous dysplasia or other musculoskeletal or endocrinological diseases [4,5] or through massive violence during labour or through accidents [2,3,6]. No case of domestic violence in an infant has yet been reported.

In the case of an infant who has already learnt to walk and now refuses to put weight on one leg, the attending physician should be alert. Imaging is necessary, at least by ultrasound. Early diagnosis and investigation of the underlying pathology is necessary to avoid complications such as varus deformity, avascular necrosis, heterotopic new bone formation, non-union and premature closure of the growth plate [6]. Fortunately, these have not occurred in our patient.

What is the correct treatment for slipped capital femoral epiphysis in an infant? In cases of obstetric trauma, spica casts with traction are often used and, in individual cases, pin osteosynthesis [3]. For children under 3 years of age, reduction and appropriate fixation is recommended [6]. Due to the massive instability of the head, we chose a 3.5 partially threaded screw and an additional K-wire for rotational stability. Overall, the great healing potential of the femoral head at this age should be emphasised. Despite the lack of blood flow on MRI and intraoperatively, the hip developed well over the next 2.5 years.

In everyday medical practice, however, it is important to consider domestic violence in the case of injuries that are not age-related. In our case, this possible cause was always openly discussed with the mother. She was also always cooperative and agreed to open communication with the youth welfare office. In the best interests of the child, a report should also be made repeatedly to the youth welfare office. In this case, three times, until the mother was finally able or willing to leave the environment that was endangering the child’s welfare.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures): The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: No funding was secured for this study.

Role of Funder/Sponsor (if any): none.

Clinical Trial Registration (if any): none.

Informed consent: As part of the inpatient treatment contract, patients also agree to a pseudonymised scientific publication of their case.

Contributor’s statement page: Katharina Susanne Gather: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing original draft, Project administration. Sebastien Hagmann: Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing review & editing. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- Cotton EV, Fowler SC, Maday KR. (2022) A review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. JAAPA. 35:39-43.

- Denes J, Weil S. (1964) Proximal Epiphysiolysis of the Femur during Caesarean Section. Lancet. 1:906-7.

- Prevot J, Lascombes P, Blanquart D, Gagneux E. (1989) [Labor trauma-induced epiphysiolysis of the proximal femur. 4 cases]. Z Kinderchir. 44:289-92.

- Kozlowski K, Braune M, Scougall JS. (1980) Multiple fractures in early infancy: report of two unusual cases. Rofo. 133:312-6.

- Shaw KA, Shiver AL, Oakes T, Fletcher ND. (2022) Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis Associated with Endocrinopathy: A Narrative Review. JBJS Rev. 10.

- Milgram JW, Lyne ED. (1975) Epiphysiolysis of the proximal femur in very young children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975:146-53.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.