Transient Global Amnesia and Verbiage as First Symptoms of Takayasu Arteritis/Giant Cell Arteritis in a 75-Year-Old Woman

by Antonio Bechara Ghobril1, Wenceslao M Calonge1*, Drahoslava Lesbros-Pantoflickova1, Elena Rizzo2, Vitali Verin3, Antonio Carota4, Jean-Michel Zabot5

1Department of Internal Medicine, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

2Department of Radiology, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

3Department of Cardiology, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

4Department of Neurology, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

5Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

*Corresponding Author: Wenceslao M Calonge, Department of Internal Medicine, Clinique de Genolier, Genolier, Switzerland

Received Date: 16 January 2026

Accepted Date: 21 January 2026

Published Date: 23 January 2026

Citation: Bechara Ghobril A, Calonge WM, Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Rizzo E, Verin V, et al. (2026). Transient Global Amnesia and Verbiage as First Symptoms of Takayasu Arteritis/Giant Cell Arteritis in a 75-Year-Old Woman. Ann Case Report. 11: 2511. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102511

Abstract

The age at onset in most patients of Takayasu arteritis is less than 40 years while classical giant cell arteritis features a later diagnosis. We report a 75-years-old woman who presented a temporary memory loss, disorientation and verbal agitation for a couple of hours. Detailed work-up one week after the initial event included cardiologic assessment, ultrasonography, angio-MRI and PET-scan.

Keywords: Takayasu Arteritis; Giant Cell Arteritis; Acute Ischemic Stroke; Transient Amnesia; Verbiage.

Case Presentation

While talking on the phone to her relatives, a 75-year-old Swedish woman showed a memory loss about recent, family events. According to her acquaintances, disorientation and verbiage persisted for 3 hours without any ataxia or paresis or sensory disturbances.

On arriving to the nearest emergency room, these warning symptoms had wiped out without any remnant manifestation. She had an ongoing treatment of Coveram ® (perindopril 5 mg and amlodipine 10 mg) for hypertension and pantoprazole 40 mg for gastric reflux. Her medical history included a hysterectomy after diagnosis of myoma 15 years ago and an operation for a cataract in her left eye 2 months before this episode. The patient had a very slight alcohol and tobacco consumption. Family health history included a sister with a TIA event the previous year. An initial CT showed no stroke signs but a 2-cm-wide mass suggested a left frontal meningioma. Though TIA could not be completely ruled out, she returned to her home next morning with an initial prescription of 75 mg acetylsalicylic acid daily.

On deeper cardiologic exam the following week in another Clinic (and another country), the patient also complained about “tired arms” whenever she had to hold both upper limbs in anteversion. Blood pressure on her right arm revealed 165/95 mmHg values.

She also referred that her home device to measure blood pressure was unreliable since 3 months ago. She had not any visual problems nor temporal headaches nor jaw pain. On cardiologic exam, radial and humeral pulses were not found on her left upper limb. Pulses on the right side were difficult to measure.

An echocardiography displayed a dilation of the ascending aorta (more than 45 mm than expected as normal for her age and weight,) left subclavian occlusion and severe stenosis of the right subclavian artery. Cardiac stress test was considered as negative with a good evolution of heart rate and blood pressure along the test.

Laboratory tests presented a mild inflammatory response: CRP 8.8 mg/l; ESR 24 mm/h; Thrombocytosis 462 G/l, HbA1c 5.6%. Liver function tests, kidney function tests and random blood sugar were normal.

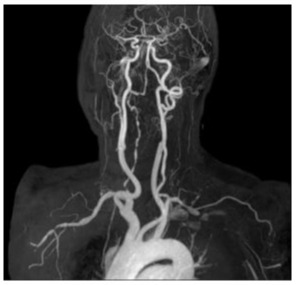

Angio-MRI with Dotarem® (meglumine gadoterate) showed strong acquisition of contrast on the walls of brachyocephalic trunk, both subclavian arteries and right vertebral artery. (Figure 1A, Figure 1B).

Figure 1A: Angio-MRI (21.3.2018) of the supraaortic vessels that shows irregularity of the right subclavian artery with subocclusion, irregular appearance of the right vertebral artery.

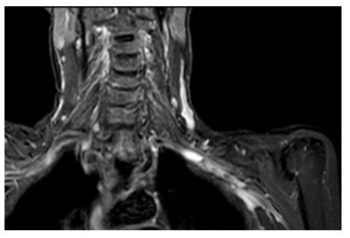

Figure 1B: STIR MRI coronal plane: hypersignal of the wall of the right subclavian artery.

A PET Computed Tomography Angiography (Figure 2) confirmed inflammatory features on both aortic branches.

Figure 2: PET CTA (23.3.2018) showing hypercaptation in vascular structures (subclavian artery).

First specific treatment consisted of prednisone 60 mg /d p.o. that was progressively decreased to 7.5 mg/d p.o. along the next six months. It was substituted by Actemra® (tocilizumab) s.c. every week but this frequency had to be decreased to one injection every two weeks to prevent neutropenia.

As a result of an accidental fall, four months after the onset of treatment the patient suffered a fracture of her right tibial medial plateau that required osteosynthesis.

Fosamax® (alendronate) 70 mg was administered weekly and substituted by Prolia® 60 mg (denosumab) every 6 months. Adjuvant treatments involved calcium, magnesium and vitamin D3 oral supplements as well as acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg on a daily basis.

Discussion

Typical onset of Takayasu arteritis happens before 40 years of age and less than 10% of patients have a later diagnosis [1-3]. Classical criteria for the diagnosis of the condition list an age less than 40 years in first place, with clinical signs (attenuation or disappearance of brachial pulse, limb claudication, subclavian murmur or abdominal aortic murmur) prominently featuring in the score. Hypertension is a characteristic feature. There seems to be an association between hypertensive episodes and arteritis aggravation. Weight loss, fever and asthenia are frequently observed [4-8]. Distribution of lesions in Takayasu arteritis usually involves the aorta and its major branches (mostly subclavian branches). There is some difficulty to tell apart Takayasu arteritis and other kinds of giant-cell arteritis [9-11]. Giant cell arteritis usually affects older adults after 50 years of age and it touches the cranial branches of the aorta such as the temporal arteries. It usually shows with fatigue, chronic headache, and scalp tenderness, fever and vision loss in its most alarming presentations. Giant cell arteritis seems more prevalent in Northern European populations (this patient) while Takayasu arteritis appear to prevail in people of East Asian descent.

As their features overlap, there is a somewhat arbitrary boundary for diagnostic labelling; the two conditions may be different manifestations in a continuum awaiting a precise, molecular characterisation. Takayasu arteritis is caused by chronic granulomatous inflammation of major vessels. It is mediated by Th1 CD4+ lymphocytes and macrophages. It involves a thick adventitial layer, infiltration of median muscular layer and endothelial hyperplasia [12-14]. On the other hand, giant cell arteritis shows less adventitial scarring and more damage on the inner layers.

Arteriography is still the landmark image technique in the criteria though other available diagnostic options include Doppler ultrasonography, MRI and PET-scan. These techniques may identify thickening of the vessel walls as well as stenosis, collateral circulation and aneurysms. PET-scan provides information about inflammatory activity even before the establishment of morphological features. However, MRI is recommended as main technique by EULAR Task Force [15-16].

Options in case of refractory arteritis despite first-line treatment with corticoids include immunosuppressive agents that were not necessary in this patient [17].

References

- Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Gordano J, Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, et al. (1994). Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 120: 919-929.

- Antón E. (2005). Large vessel arteritis: a diagnostic challenge in the elderly. J Clin Pathol. 58: 782.

- Lalhmachhuani PC, Daimei SL, Ralte RL, Manpang NN, Jaleel M. (2017). A case of Takayasu arteritis in elderly male patient. Indian Journal of Medical Research and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 4: 34-38.

- Johnston SL, Lock RJ, Gompels MM. (2002). Takayasu arteritis: a review. J Clin Pathol. 55: 481-486.

- Maffei S, Di Renzo M, Bova G, Auteri A, Pasqui AL. (2006). Takayasu’s arteritis: a review of the literature. Intern Emerg Med. 1: 105-112.

- Quéméneur T, Hachulla E, Lambert M, Perez-Cousin M, Queyrel V, et al. (2006). Takayasu arteritis. Presse Med. 35: 847-856.

- Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Calabrese LH, et al. (1990). The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 33: 1129-1134.

- Fiessinger JN, Tawfik-Taher S, Capron L, Laurian C, Cormier JM, et al. (1982). Takayasu’s disease: diagnostic criteria. Nouv Presse Med. 11: 583-586.

- Michel BA, Arend WP, Hunder GG. (1996). Clinical differentiation between giant cell (temporal) arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis. J Rheumatol. 23: 106-111.

- Brack A, Martinez-Taboada V, Stanson A, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. (1999). Disease pattern in cranial and large-vessel giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 42: 311-317.

- Watanabe R, Berry GJ, Liang DH, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. (2020). Pathogenesis of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis: similarities and differences. Current Rheumatology Reports. 22: 1-11.

- Singh K, Rathore U, Rai MK, Behera MR, Jain N, et al. (2022). Novel Th17 lymphocyte populations, Th17.1 and PD1+ Th17 are increased in Takayasu arteritis, and associate with active disease. Journal of Inflammation Research. 15: 1521-1541.

- Kong X, Xu M, Cui X, Ma L, Cheng H, et al. (2021). Potential role of macrophage phenotypes and CCL2 in the pathogenesis of Takayasu arteritis. Frontiers in Immunology. 12: 646516.

- Paroli M, Caccavale R, Accapezzato D. (2024). Giant cell arteritis: advances in understanding pathogenesis and implications for clinical practice. Cells. 13: 267.

- Ma LY, Wu B, Jin XJ, Sun Y, Kong XF, et al. (2022). A novel model to assess disease activity in Takayasu arteritis based on 18F-FDG-PET/ CT: a Chinese cohort study. Rheumatology. 61: SI14-SI22.

- Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Bond M, Bosch P, Ponte C, et al. (2024). EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice: 2023 update. Ann Rheumatic Diseases. 83: 741-751.

- Yoshida S, Suzuki E, Matsumoto H, Yokose K, Fujita Y, et al. (2023). Effectiveness of combination tocilizumab and glucocorticoids as an induction therapy in patients with Takayasu arteritis: an observational study. Modern Rheumatology. 33: 360-366.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.