The Role of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Oligometastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Narrative Review with Emphasis on EGFR-Mutant Tumors

by Ioannis Georgakopoulos1*, Georgios Nikiforos Ntoumas1, Pantelis Skarlos2, Georgia Lymperopoulou1, Alexia Sidiropoulou1, Manolis Verigos1, Dimitra Desse1, Ioannis Aletras3, Areti Gkantaifi4, Andrianni Charpidou5, Maria Tolia3

1Radiation Oncology Unit, 1st Department of Radiology, Medical School, Aretaieion Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Vas. Sofias 76, 115 28 Athens, Greece.

2Radiation Oncology Department, General University Hospital of Larissa, Greece.

3Department of Radiotherapy, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece.

4Laboratory of Oncological Radiotherapy, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece.

5Third Department of Internal Medicine and Laboratory, Athens Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Sotiria General Hospital.

*Corresponding author: Georgakopoulos I, Radiation Oncology Unit, 1st Department of Radiology, Medical School, Aretaieion Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Vas. Sofias 76, 115 28 Athens, Greece.

Received Date: 19 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 26 January, 2026

Published Date: 29 January, 2026

Citation: Georgakopoulos I, Ntoumas GN, Skarlos P, Lymperopoulou G, Sidiropoulou A, et al. (2026) The Role of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Oligometastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Narrative Review with Emphasis on EGFR-Mutant Tumors. J Oncol Res Ther 11:10326. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10326

Abstract

The concept of oligometastatic disease has evolved into a clinically relevant entity, particularly in non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), where a subset of patients with limited metastatic burden may benefit from aggressive local treatment. Radiotherapy, and especially stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), allows delivery of ablative doses with high precision and acceptable toxicity, making it a central modality in this setting. This review evaluates the available evidence supporting the use of radical radiotherapy in oligometastatic NSCLC, with particular emphasis on tumors harboring targetable mutations, especially epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) alterations. A comprehensive review of the published literature and ongoing clinical trials was performed, focusing on synchronous oligometastatic, oligopersistent, and oligoprogressive disease states. In unselected NSCLC populations, randomized data demonstrate heterogeneous results, with benefits highly dependent on patient selection, disease biology, and treatment context, particularly in the immunotherapy era. In contrast, evidence in EGFR-mutant NSCLC is more consistent. Multiple prospective and randomized studies indicate that local ablative therapy can significantly prolong progression-free survival and, in several settings, overall survival when combined with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Benefit has been observed in oligoresidual, oligoprogressive, and upfront treatment strategies, with increasing support for inclusion of the primary tumor in the radiotherapy field. Ongoing trials are expected to further define optimal timing, patient selection, and integration with contemporary systemic therapies.

Keywords: Lung Cancer; Oligometastatic; Stereotactic Radiotherapy; Epidermal-Growth-Factor-Receptor.

Introduction

Since the introduction of the term oligometastatic disease by Weichselbaum and Hellman, much has been written on the subject. Although a clear and universally accepted definition of oligometastatic disease in solid tumors has not yet been established, it appears that it indeed represents a distinct clinical entity, characterizing the intermediate stage between localized and widely disseminated systemic disease, for which there is clear therapeutic benefit from the application of local ablative treatment, mainly surgery or radiotherapy.

Among malignancies in which the concept of oligometastatic disease is highly relevant is non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In both squamous cell carcinoma and, more commonly, lung adenocarcinoma diagnosed at an oligometastatic or oligoprogressive stage, extensive international literature demonstrates a clear benefit from the application of local ablative therapy, mainly surgical metastasectomy or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT).

The aim of this article is to review the relevant literature in order to assess whether mature data now exist supporting the application of radical radiotherapy in the context of oligometastatic disease, both for NSCLC in general and more specifically for cancers harboring oncogenic driver mutations, particularly mutations of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR).

Materials and Methods

A search of the published literature was conducted across the PubMed database, employing the keywords “oligometastases”, “oligoprogression”, “non-small cell lung cancer”, “stereotactic body radiotherapy or SBRT”, “stereotactic ablative radiotherapy or SABR”, “local ablative therapy or LAT” and “local consolidative therapy or LCT” in order to identify studies relevant to the use of local ablative treatment strategies. Only articles published in English were included, and no filters regarding study design or country of origin were applied. In addition, the ClinicalTrials.gov database was reviewed to identify ongoing relevant studies.

Results

Definitions

Biologic Effective Dose

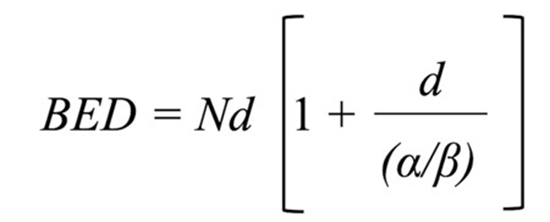

A fundamental parameter in radiation oncology is the Biologic Effective Dose (BED), which is primarily determined by the intrinsic radiosensitivity of tissues, indicating tissue and tumor sensitivity to fraction size in radiotherapy. BED is calculated using a specific mathematical formula and depends on the number of radiation fractions, the dose per fraction, and most importantly on the radiosensitivity of the tissue, expressed as the α/β ratio (Figure 1).

Without delving into radiobiological details beyond the scope of this article, it should be noted that BED differs for each tissue type, whether malignant or normal, and also varies depending on whether the total dose is delivered in a small number of fractions with a high dose per fraction or in many fractions with a lower dose per fraction [1, 2].

A characteristic example is NSCLC, for which the α/β ratio is generally assumed to be approximately 10 Gy. If the conventional dose for radical radiotherapy of 64 Gy is delivered in 32 fractions, the biologically effective dose is 76.8 Gy. If almost the same total dose of 60 Gy is delivered stereotactically in 3 fractions of 20 Gy each, the resulting BED is 180 Gy. This increase in biologically effective dose confers a clear therapeutic advantage, as demonstrated in multiple studies. Indicatively, in the study by Onishi et al., patients with stage I NSCLC treated with stereotactic radiotherapy, a BED greater than 100 Gy was associated with statistically significant improvements in both local control and survival [3].

Figure 1: Biologic Effective Dose (BED); N: number of fractions; d: daily dose, α/β: ratio of radiosensitivity index Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy or Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy.

A widely accepted definition of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) is that it involves the delivery of a high radiation dose with stereotactic precision over a small number of fractions. More specifically, stereotactic radiotherapy refers to external beam radiotherapy that delivers a very high radiation dose with high precision in one or very few fractions [4-7].

Technically, treatment is considered stereotactic when the BED exceeds 100 Gy, with a high radiation dose and a steep dose gradient beyond the target volume. The goal is to treat the entire tumor volume with an extremely efficient and biologically destructive therapy while simultaneously sparing the surrounding normal tissues, achieving high local tumor control with minimal severe toxicity.

Oligometastatic NSCLC

According to the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC is defined as disease with a maximum of five (5) metastatic lesions in a maximum of three (3) involved organs, provided that all lesions are amenable to radical ablative treatment with acceptable minimal toxicity [8].

A more detailed definition is provided by the joint consensus of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) and the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO), which also describes the various subtypes of oligometastatic disease. In general, oligometastatic disease refers to patients with up to five (5) metastases detected by appropriate imaging, all of which can be treated with curative intent, provided that this is technically feasible and clinically safe. The consensus further specifies that in cases of synchronous, metachronous, or oligopersistent oligometastatic disease, definitive ablative therapy should be applied to all disease sites in addition to standard-ofcare systemic therapy, whereas in oligoprogressive disease, the application of local stereotactic therapy to all progressing sites allows continuation of the current line of systemic therapy [9].

Oligometastatic NSCLC In General

Synchronous Oligometastatic Disease

The rationale for upfront definitive local therapy in synchronous oligometastatic disease is that even combination systemic therapy with optimal targeted agents or immunotherapy remains imperfect. Positive trials such as KEYNOTE-189 have demonstrated that the addition of immunotherapy, specifically pembrolizumab, to chemotherapy provides statistically significant benefits in disease progression and overall survival; however, there remains considerable room for improvement in therapeutic outcomes [10].

When this is combined with the increased detection of oligometastatic disease due to modern imaging modalities such as PET/CT, the question arises as to whether there exists a subset of patients with NSCLC who may benefit from upfront or early definitive local therapy in addition to contemporary standard-ofcare systemic therapy.

The well-known SABR-COMET trial by Palma et al., including updated results published in 2020, demonstrated a clear benefit from the addition of stereotactic radiotherapy to standard systemic therapy. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate was 17.7% with standard-of-care therapy alone versus 42.3% with the addition of definitive local therapy (arm 2) (95% CI, 28%–56%; stratified logrank P = .006). No new grade 2–5 adverse events were observed, and there were no differences in quality of life between treatment arms. Despite the relatively small patient cohort, extended followup confirmed that the impact of SBRT on OS was clear and durable over time [11].

This critical question has prompted the development of trials specifically addressing synchronous oligometastatic NSCLC, such as the SARON trial, which examines the combination of chemotherapy with SABR, and the TRAP-OLIGO study, which evaluates the combination of local ablative therapy (LAT), stereotactic radiotherapy or surgery with chemotherapy and immunotherapy [12, 13].

Oligopersistent Disease

In the contemporary era of optimal systemic therapy, especially with the addition of immunotherapy, most patients with stage IV NSCLC achieve either a response or stable disease. Multiple studies have demonstrated that, following initial response, disease progression often occurs at sites present prior to the initiation of first-line systemic therapy [14, 15]. This observation raises the question of whether the application of LAT to oligometastatic lesions as consolidation after initial response could enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Iyengar et al., in a well-designed prospective phase II study involving a small patient cohort, investigated the application of SABR prior to maintenance therapy versus maintenance therapy alone in patients with limited metastatic NSCLC. Consolidative SABR demonstrated a clear benefit by tripling PFS, with no significant difference in toxicity. The investigators concluded that irradiation prevented local failures at original disease sites, which are the most likely locations of first recurrence [16].

Similarly, in a study by Gomez et al., patients with three or fewer metastases and no disease progression after at least three months of front-line systemic therapy were randomized to either local consolidative therapy (LCT), radiotherapy or surgery followed by standard maintenance or observation (LCT arm) or to standard maintenance or observation alone (MT/O arm). The trial was terminated early due to impressive results, demonstrating a clear PFS benefit in the LCT arm. With a median follow-up of nearly 40 months, the PFS benefit remained durable (14.2 months versus 4.4 months), and an OS benefit was also observed, without additional grade ≥3 toxicities [17].

To date, the only randomized phase III data come from the NRG-LU002 trial, which presented preliminary results in 2024. This trial represents one of the largest prospective randomized studies in oligometastatic NSCLC assessing the value of adding LCT (radiotherapy or surgery) after initial systemic therapy in the immunotherapy era. Patients with oligometastatic NSCLC (≤3 extracranial metastases) who achieved at least stable disease after four cycles of first-line systemic therapy (chemotherapy and/ or immunotherapy) were randomized to maintenance systemic therapy alone versus LCT plus maintenance systemic therapy. Contrary to earlier studies, the addition of LCT did not confer a benefit in either PFS or OS (reported hazard ratios 0.93 and 1.05, respectively), while an increased incidence of significant (grade ≥3) pneumonitis was also observed in the LCT arm [18].

Oligoprogressive Disease

Oligoprogressive disease represents another distinct clinical entity within the spectrum of oligometastatic disease. After an initial response to systemic therapy, which is now a frequent occurrence in the immunotherapy era, patients may eventually develop progression in a limited number of sites. The key clinical question is whether to continue the same line of therapy, switch to the next line, add another systemic agent, or apply LAT to the progressing lesions.

The STOP trial investigated the benefit of adding SABR to standard-of-care systemic therapy in patients with ≤5 sites of oligoprogression. Initially limited to NSCLC, the trial was later expanded to include other malignancies meeting accrual criteria. Ninety patients with 127 oligoprogressive metastases (44% of cases NSCLC) were randomized to SABR plus continuation of the same systemic therapy versus standard of care, which included continuation of the same agent, switching to a new agent, or observation. After a median follow-up of 31 months, no difference in PFS or OS was observed. SABR was well tolerated, with excellent toxicity profiles (no grade 4–5 adverse events), and clearly improved lesional control, but with PFS or OS benefit [19].

Another recent trial is the CURB study, which included patients with oligoprogressive disease with up to five extracranial metastases from NSCLC or breast cancer. Patients were randomized to continuation or change of systemic therapy versus SBRT to all oligoprogressive lesions with continuation of the same systemic therapy. While no benefit was observed in breast cancer patients, NSCLC patients demonstrated a clear benefit from SBRT, with a median PFS of 10 months versus 2.2 months in the control arm (p = 0.0039). Investigators concluded that oligoprogression in metastatic NSCLC can be effectively treated with SBRT plus standard-of-care systemic therapy, leading to more than a four-fold increase in progression-free survival [20].

Oligometastatic NSCLC with Oncogenic Driver Mutations

Since the early 2000s, it has become evident that specific oncogenic mutations play a crucial role in NSCLC biology and progression. The most clinically relevant involve genes encoding the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK). A major therapeutic breakthrough was achieved with the development of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), which resulted in significant clinical responses and generally lower toxicity compared with platinum-based chemotherapy [21].

A well-recognized clinical challenge in TKI therapy is the gradual development of resistance, which may arise from EGFR-dependent or EGFR-independent mechanisms [22]. In order to delay or prevent resistance and prolong clinical benefit, combination strategies have been explored, including mainly combinations with chemotherapy, other targeted agents, and ionizing radiation [23].

Numerous preclinical studies have investigated the combination of TKIs with radiotherapy and have demonstrated a clear benefit, suggesting a synergistic effect mediated through multiple mechanisms that enhance radiobiological response [24-27]. Baumann described the key mechanisms including direct killing of cancer stem cells, cellular radiosensitization, inhibition of DNA damage repair, reduced tumor repopulation, and improved tumor reoxygenation [28].

These findings prompted clinical studies evaluating combined TKI and radiotherapy in NSCLC. A critical issue in this context is the optimal timing of radiotherapy, which has been explored mainly in oligoprogressive and oligoresidual disease, with emerging data supporting upfront radiotherapy in EGFR-mutant oligometastatic NSCLC.

SBRT for oligoprogressive metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC

In a retrospective analysis, Schuler et al. examined progression patterns in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients treated with first-line TKIs, specifically osimertinib. Up to 47% of patients developed oligoprogressive disease. Compared with patients experiencing systemic progression, oligoprogressive patients had significantly longer median time to treatment failure (23 vs 11 months; p < 0.001) and better OS (52 vs 26 months; p = 0.004). Notably, approximately 40% of oligoprogressive patients had disease amenable to SBRT. This raises the question of whether SBRT to oligoprogressive lesions could enhance treatment outcomes apart from continuation of same TKI [29].

Although mature data are still limited, most studies evaluating SBRT in oligoprogressive disease with driver mutations have demonstrated a clear benefit [30-34]. A 2024 review study including these relevant data, confirmed that LAT for oligoprogressive disease provides clear therapeutic benefit by prolonging continuation of the same TKI by 6 to 14 months [35]. Results from the HALT trial, a randomized phase II/III study evaluating SBRT to ≤3 oligoprogressive sites in combination with continued TKI therapy, are expected to clarify whether this approach improves PFS [36].

SBRT for Oligoresidual Metastatic EGFR-Mutant NSCLC

Miyawaki et al. in a retrospective analysis of 207 patients investigated the association between oligoresidual disease and patterns of failure in EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients. Oligoresidual disease was defined as the presence of 1–4 lesions (including the primary tumor) at three months after treatment initiation. In 73% of patients with oligoresidual disease, progression occurred predominantly at residual sites, providing a strong rationale for LAT to all residual lesions [37].

Data are mostly limited to small series or single-arm studies, such as the recent phase II trial by Sabath et al., which demonstrated that consolidative SBRT plus TKIs is safe, effective, and prolongs clinical benefit. With a median follow-up of 35.7 months, median PFS was 32.3 months, median OS 45 months, and median duration of osimertinib administration 32.4 months [38].

Randomized data are provided by the phase II trial of Peng et al., in which patients with EGFR-mutant metastatic NSCLC with up to five metastases who achieved stable disease or partial response after three months of TKI therapy were randomized to SBRT plus TKI versus TKI alone. After a median follow-up of nearly 30 months, PFS was 17.3 months in the SBRT arm versus 9 months in the TKI-alone arm (p = 0.015), and OS was 33.6 versus 23.2 months, respectively (p = 0.033). The investigators concluded that SBRT significantly prolonged both PFS and OS [39].

Early or upfront SBRT for EGFR-mutant oligometastatic NSCLC

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Seong et al. evaluated the efficacy and safety of LAT in combination with first-line EGFR-TKIs prior to disease progression. Local therapies included radiotherapy, surgery, and ablation, with SBRT accounting for 91% of included studies. The combination of LAT with TKIs resulted in statistically significant improvement in both PFS and OS, without an increase in grade ≥3 toxicity. The authors concluded that early application of LAT during first-line TKI therapy and prior to progression is clearly meaningful in EGFRmutant NSCLC [40].

The most well-known randomized study included in the above mentioned meta-analysis is the SINDAS trial. EGFR-mutant NSCLC patients receiving first-line TKI were randomized to upfront radiotherapy versus no radiotherapy. Eligibility criteria included treatment-naïve synchronous oligometastatic disease with ≤5 metastases in ≤2 lesions per organ. Interim analysis published in 2023 demonstrated significant benefits in both PFS (20 vs 12.5 months, p < .001) and OS (25.5 vs 17.4 months, p < .001). The combination was well tolerated, with no grade 5 toxicity and symptomatic pneumonitis observed in only 6%. Based on these clear results, the trial’s ethics committee recommended early termination [41].

Another highly relevant study is the NORTHSTAR trial. Patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC, TKInaïve or with acquired T790M mutation but without prior thirdgeneration TKI therapy, were randomized after 6–12 weeks of osimertinib and absence of progression to either continuation of osimertinib alone or osimertinib combined with local therapy (surgery or SBRT). Early results presented at ESMO 2025 demonstrated a clear benefit in median PFS (17.5 vs 25.3 months; hazard ratio 0.66), corresponding to a 34% reduction in progression risk. Subgroup analyses showed benefit across mutation subtypes (exon 19 deletion, L858R) and in patients with multiple metastatic sites. Notably, patients receiving comprehensive LCT targeting all detectable disease exhibited particularly strong PFS benefit [42, 43].

The provocative issue of treating the primary tumor in oligometastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC

Important insights regarding the value of irradiating the primary tumor even in the oligometastatic setting emerged from the SINDAS trial. A critical feature of this study was that SBRT was mandated to all disease sites, explicitly including both the primary lung tumor and all synchronous oligometastatic lesions (≤5). Therefore, the observed PFS and OS benefit cannot be attributed solely to metastasis-only ablation [41].

Although SINDAS did not publish a failure-pattern subanalysis, its results are biologically consistent with multiple observations indicating that the primary tumor is often the largest and most heterogeneous lesion, harboring resistant subclones. Even under TKI therapy, the primary tumor frequently becomes the dominant site of first progression if left untreated. In this context, an uncontrolled primary tumor may reseed metastatic sites [44, 45].

Other randomized data also support the value of treating the primary tumor. In the aforementioned study by Peng et al., a subgroup analysis of patients receiving treatment to the primary tumor demonstrated clear benefit in both median PFS and OS [39].

Finally, results from the phase III NROG China-002 trial were recently published. Patients with oligo-organ metastatic EGFRmutant NSCLC were randomized to TKI therapy alone with icotinib versus TKI plus radiotherapy to the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes. Compared with TKI alone, the TKI plus thoracic radiotherapy group achieved significantly improved PFS (hazard ratio 0.57; p = .004) and OS (hazard ratio 0.62; p = .029). Median PFS was 10.6 months versus 17.1 months, and median OS was 26.2 versus 34.4 months, respectively [46].

|

Clinical Setting |

Population |

Study / Trial |

Study Design |

Local Therapy |

Key Outcome(s) |

Interpretation |

|

Synchronous oligometastatic disease |

Mixed solid tumors (incl. NSCLC) |

SABR- COMET [11] |

Randomized phase II |

SABR added to SOC |

OS benefit (5year OS 42.3% vs 17.7%); no QoL detriment |

Proof-of-concept for survival benefit of SABR |

|

NSCLC |

SARON [12] |

Phase III (ongoing) |

Chemotherapy ± SABR |

OS (pending) |

Definitive evidence awaited |

|

|

NSCLC |

TRAP-OLIGO [13] |

Phase II (ongoing) |

Surgery/SBRT + chemo–IO |

PFS/OS (pending) |

Multimodal intensification under evaluation |

|

|

Oligopersistent disease after response |

Limited metastatic NSCLC |

Iyengar et al. [16] |

Randomized phase II |

Consolidative SABR + maintenance vs maintenance |

PFS improvement |

Supports consolidative SABR in selected responders |

|

NSCLC (≤3 metastases) |

Gomez et al. [17] |

Randomized phase II |

LCT (RT or surgery) |

Durable PFS benefit; OS benefit |

Strong signal favoring LCT |

|

|

NSCLC (IO era; ≤3 extracranial metastases) |

NRG-LU002 [18] |

Randomized phase III |

LCT + maintenance vs maintenance |

No PFS/OS benefit; ↑ grade ≥3 pneumonitis |

Argues against routine LCT for all patients |

|

|

Oligoprogressive disease |

Mixed tumors (44% NSCLC) |

STOP [19] |

Randomized phase II |

SABR to OPD sites |

No PFS/ OS benefit; excellent lesional control |

Local control without clear survival gain |

|

NSCLC & breast cancer |

CURB [20] |

Randomized phase II |

SBRT to all OPD sites + SOC vs SOC |

PFS benefit in NSCLC subgroup |

Suggests disease-specific benefit in NSCLC |

|

|

Abbreviations: IO: immunotherapy; LCT: local consolidative therapy; OPD: oligoprogressive disease; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; QoL: quality of life; SABR/SBRT: stereotactic ablative/body radiotherapy; SOC: standard of care. |

||||||

Table 1: Clinical Evidence for Local Ablative Therapy in Oligometastatic NSCLC.

|

Clinical Setting |

Population |

Study / Trial |

Study Design |

Local Therapy Strategy |

Key Outcome(s) |

Interpretation |

|

Oligoprogressive disease on EGFR-TKI |

EGFR-mutant NSCLC (on osimertinib) |

Schuler et al. [29] |

Retrospective |

Patterns of progression; SBRT-amenable OPD subset |

OPD frequent; subset eligible for SBRT |

Identifies target population for LAT on TKI |

|

EGFR/drivermutant NSCLC |

Georgakopoulos et al. [35] |

Review of clinical series |

LAT to OPD sites while continuing same TKI |

Prolongs TKI continuation ~6–14 months |

Consistent clinical signal |

|

|

Mutationpositive advanced NSCLC |

HALT [36] |

Randomized phase II/III (ongoing) |

SBRT to ≤3 OPD sites + continue TKI vs TKI alone |

PFS (pending) |

Prospective validation awaited |

|

|

Oligoresidual disease after initial TKI response |

EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

Miyawaki et al. [37] |

Retrospective |

Defines oligoresidual disease; failure patterns |

Progression predominantly at residual sites |

Clinical rationale supporting LAT to residual sites |

|

EGFR-mutant NSCLC on osimertinib |

Sabath et al. [38] |

Phase II, single- arm |

Consolidative SRT + TKI |

Promising PFS/OS; prolonged osimertinib duration |

Supports feasibility/safety; nonrandomized |

|

|

EGFR-mutant NSCLC (≤5 metastases) |

Peng et al. [39] |

Randomized phase II |

SBRT + continue TKI vs TKI alone |

Improved PFS and OS |

Randomized evidence supporting consolidation |

|

|

Early or upfront LAT before progression |

EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

Seong et al. [40] |

Systematic review/ meta-analysis (clinical studies) |

LAT (mostly SBRT) + 1L EGFR-TKI before PD |

Significant PFS and OS benefit; no excess grade ≥3 toxicity |

High-level summary evidence |

|

Treatmentnaïve synchronous oligometastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC |

SINDAS [41] |

Randomized trial (interim analysis; stopped early) |

Upfront SBRT to all sites incl. primary + TKI vs TKI alone |

Improved PFS and OS; low severe toxicity |

Strong clinical signal for comprehensive LAT |

|

|

EGFR-mutant NSCLC on osimertinib |

NORTHSTAR [42,43] |

Randomized phase II |

Osimertinib ± LCT (surgery/SBRT) |

PFS benefit (HR ~0.66); greater benefit with comprehensive LCT |

Supports “treat-allsites” approach |

|

|

Treating the primary tumor (thoracic RT) |

EGFR-mutant oligo-organ metastatic NSCLC |

NROG China-002 [46] |

Randomized phase III |

TKI ± thoracic RT |

Improved PFS and OS |

High-level evidence for thoracic/primary control |

|

Abbreviations: 1L: first-line; LAT: local ablative therapy; LCT: local consolidative therapy; OPD: oligoprogressive disease; PD: progression of disease; PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; RT: radiotherapy; SRT/SBRT: stereotactic radiotherapy/body radiotherapy; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

||||||

Table 2: Clinical Evidence for Local Ablative Radiotherapy in EGFR-Mutant Oligometastatic NSCLC.

Discussion

The concept of oligometastatic disease has progressively evolved from a theoretical issue to a clinically true state, particularly in NSCLC. Accumulating evidence supports the concept that a subset of patients with limited metastatic burden may derive meaningful benefit from aggressive local therapy in addition to systemic treatment. Radiotherapy, and especially stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT/SABR), has emerged as a central modality in this setting due to its ability to deliver ablative doses with high precision and acceptable toxicity (Table 1).

Evidence supporting local consolidative radiotherapy is heterogeneous. Early randomized phase II trials demonstrated substantial improvements in PFS and, in some cases, OS when LAT was added after initial response to systemic treatment. However, these encouraging results were largely generated before the widespread incorporation of immune checkpoint inhibitors. The negative findings of the NRG-LU002 trial in the immunotherapy era highlight the complexity of integrating local therapies with modern systemic regimens and underscore the importance of appropriate patient selection, careful assessment of disease biology, and treatment-related toxicity. These discrepancies suggest that oligometastatic NSCLC is not a uniform entity and that radiotherapy benefit is likely confined to biologically favorable subgroups.

As far as oligoprogressive disease it represents a more refined clinical scenario in which radiotherapy appears particularly attractive. The ability to ablate a limited number of progressing lesions while maintaining effective systemic therapy aligns with the biological rationale of delaying widespread resistance. Although not all randomized trials have demonstrated survival benefits, consistent improvements in lesion control and PFS in NSCLC support the clinical relevance of this strategy, especially when progression is limited and systemic disease remains controlled.

The strongest and most consistent evidence for the integration of radiotherapy comes from studies in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. In this population, multiple randomized and prospective studies demonstrate that LAT can significantly prolong PFS and, in several trials, OS (Table 2). Importantly, benefit has been observed across different clinical scenarios, including oligoresidual disease after initial TKI response, oligoprogressive disease during TKI therapy, and even upfront treatment in synchronous oligometastatic disease. These findings suggest that radiotherapy may delay the emergence of resistant clones, extend the duration of effective targeted therapy, and favorably alter the natural history of the disease.

A particularly relevant and increasingly supported concept is the treatment of the primary tumor in the metastatic setting. Data from randomized trials indicate that inclusion of the primary lesion within the radiotherapy field contributes to improved outcomes, supporting biological models of intratumoral heterogeneity and tumor self-seeding. In EGFR-mutant disease, where long-term disease control is achievable with targeted agents, uncontrolled primary tumors may represent a critical source of resistance and subsequent dissemination.

Despite these advances, several questions remain unresolved. Optimal timing of radiotherapy, selection of appropriate candidates, integration with third-generation TKIs and immunotherapy, and long-term safety—particularly pulmonary toxicity—require further clarification. Ongoing randomized trials and translational studies are expected to refine patient stratification and define standardized treatment algorithms.

Conclusion

Radiotherapy plays an increasingly important role in the management of oligometastatic NSCLC, with its strongest and most consistent benefit observed in EGFR-mutant disease. While evidence in unselected NSCLC remains heterogeneous, carefully selected patients—particularly those with limited, biologically favorable disease—may derive meaningful benefit from local ablative treatment. In EGFR-mutant NSCLC, integration of radiotherapy with targeted therapy can prolong disease control and survival, supporting a paradigm shift toward combined systemic and definitive local treatment in appropriately selected patients.

Author Contribution Statement

Designed research: I.G., G.L., A.C., M.T., P.S., G.N.N.; performed research : A.S., I.G., M.V., D.D., I.A., A.G., G.L.; analyzed data : I.G., M.T., G.N.N.; data acquisition : P.S., D.D.; Writing original draft: I.G.; review & editing: All. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval Statement: Not applicable.

Acknowledgments: None.

Funding: This work received no funding.

Data Availability Statement: Data generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones B, Dale RG, Deehan C, Hopkins KI, Morgan DAL (2001) The Role of Biologically Effective Dose (BED) in Clinical Oncology. Clin Oncol 13: 71-81.

- Moreno AC, Fellman B, Hobbs BP, Liao Z, Gomez DR, et al. (2020) Biologically Effective Dose in Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy and Survival for Patients With Early-Stage NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 15: 101-109.

- Onishi H, Shirato H, Nagata Y, Hiraoka M, Fujino M, et al. (2007) Hypofractionated Stereotactic Radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Updated Results of 257 Patients in a Japanese Multi-institutional Study. J Thorac Oncol 2: S94-100.

- Guckenberger M, Andratschke N, Alheit H, Holy R, Moustakis C, et al. (2014) Definition of stereotactic body radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 190: 26-33.

- Kirkbride P, Cooper T (2011) Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Guidelines for Commissioners, Providers and Clinicians: a National Report. Clin Oncol 23: 163-164.

- Potters L, Kavanagh B, Galvin JM, Hevezi JM, Janjan NA, et al. (2010) American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) and American College of Radiology (ACR) Practice Guideline for the Performance of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat OncolBiolPhys 76: 326-332.

- Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, Galvin JM, Hinson W, et al. (2010) Stereotactic body radiation therapy: The report of AAPM Task Group 101. Méd Phys 37: 4078-4101.

- Dingemans A-MC, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T, Levy A, Hasan B, et al. (2019) Definition of Synchronous Oligometastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer—A Consensus Report. J Thorac Oncol 14:2109-2119.

- Iyengar P, All S, Berry MF, Boike TP, Bradfield L, et al. (2023) Treatment of Oligometastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: An ASTRO/ESTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pr Radiat Oncol 13: 393-412.

- Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, et al. (2018) Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non–SmallCell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 378: 2078-2092.

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, Gaede S, Louie AV, et al. (2020) Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy for the Comprehensive Treatment of Oligometastatic Cancers: Long-Term Results of the SABR-COMET Phase II Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol 38: 2830-2838.

- Conibear J, Chia B, Ngai Y, Bates AT, Counsell N, et al. (2018) Study protocol for the SARON trial: a multicentre, randomised controlled phase III trial comparing the addition of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy and radical radiotherapy with standard chemotherapy alone for oligometastatic non-small cell lung cancer. BMJ Open 8: e020690.

- Miyawaki T, Kenmotsu H, Harada H, Ohde Y, Chiba Y, et al. (2024) Phase II study of multidisciplinary therapy combined with pembrolizumab for patients with synchronous oligometastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer TRAP-OLIGO study (WJOG11118L): Feasibility analysis of induction therapy and local ablative therapy. J Clin Oncol 42: 8564-8564.

- Mehta N, Mauer AM, Hellman S, Haraf DJ, Cohen EEW, et al. (2004) Analysis of further disease progression in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: implications for locoregional treatment. Int J Oncol 25: 1677-1683.

- Rusthoven CG, Yeh N, Gaspar LE (2015) Radiation Therapy for Oligometastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer J 21: 404-412.

- Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, Tumati V, Ahn C, et al. (2017) Consolidative Radiotherapy for Limited Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 4: e173501–e173501.

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, Blumenschein GR, Hernandez M, et al. (2019) Local Consolidative Therapy Vs. Maintenance Therapy or Observation for Patients With Oligometastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Long-Term Results of a Multi-Institutional, Phase II, Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol : Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 37: 15581565.

- Iyengar P, Hu C, Gomez DR, Timmerman RD, Simone CB, et al. (2024) NRG-LU002: Randomized phase II/III trial of maintenance systemic therapy versus local consolidative therapy (LCT) plus maintenance systemic therapy for limited metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 42: 8506-8506.

- Schellenberg D, Gabos Z, Duimering A, Debenham B, Fairchild A, et al. (2025) Stereotactic Ablative Radiation for Oligoprogressive Cancers: Results of the Randomized Phase 2 STOP Trial. Int J Radiat OncolBiolPhys 121: 28-38.

- Tsai CJ, Yang JT, Shaverdian N, Patel J, Shepherd AF, et al. (2024) Standard-of-care systemic therapy with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with oligoprogressive breast cancer or nonsmall-cell lung cancer (Consolidative Use of Radiotherapy to Block [CURB] oligoprogression): an open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet 403:171-182.

- Zhao J, Xu W, Zhou F, Zhang X, Zhou M, et al. (2026) Navigating the landscape of EGFR TKI resistance in EGFR-mutant NSCLC - mechanisms and evolving treatment approaches. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 23: 63-83.

- Minari R, Bordi P, Tiseo M (2016) Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer: review on emerged mechanisms of resistance. Transl Lung Cancer Res 5: 695-708.

- Papini F, Sundaresan J, Leonetti A, Tiseo M, Rolfo C, et al. (2021) Hype or hope – Can combination therapies with third-generation EGFR-TKIs help overcome acquired resistance and improve outcomes in EGFRmutant advanced/metastatic NSCLC? Crit Rev OncolHematol 166: 103454.

- Steel GG, McMillan TJ, Peacock JH (1989) The 5Rs of Radiobiology. Int J Radiat Biol 56: 1045-1048.

- Zhuang H, Sun J, Yuan Z, Wang J, Zhao L, et al. (2009) Radiosensitizing effects of gefitinib at different administration times in vitro. Cancer Sci 100: 1520-1525.

- Tanaka T, Munshi A, Brooks C, Liu J, Hobbs ML, et al. (2008) Gefitinib Radiosensitizes Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells by Suppressing Cellular DNA Repair Capacity. Clin Cancer Res 14: 1266-1273.

- Wang N, Wang L, Meng X, Wang J, Zhu L, et al. (2019) Osimertinib (AZD9291) increases radio-sensitivity in EGFR T790M non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 41:77-86.

- Baumann M, Krause M, Dikomey E, Dittmann K, Dörr W, et al. (2007) EGFR-targeted anti-cancer drugs in radiotherapy: Preclinical evaluation of mechanisms. Radiother Oncol 83: 238-248.

- Schuler A, Huser J, Schmid S, Schär S, Scherz A, et al. (2024) Patterns of progression on first line osimertinib in patients with EGFR mutationpositive advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A Swiss cohort study. Lung Cancer 187: 107427.

- Shukuya T, Takahashi T, Naito T, Kaira R, Ono A, et al. (2011) Continuous EGFR-TKI administration following radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer patients with isolated CNS failure. Lung Cancer 74:457-461.

- Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, Gan G, Lu X, et al. (2012) Local Ablative Therapy of Oligoprogressive Disease Prolongs Disease Control by Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Oncogene-Addicted Non– Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 7: 1807-1814.

- Iyengar P, Kavanagh BD, Wardak Z, Smith I, Ahn C, et al. (2014) Phase II Trial of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy Combined With Erlotinib for Patients With Limited but Progressive Metastatic Non– Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 32: 3824-3830.

- Chan OSH, Lee VHF, Mok TSK, Mo F, Chang ATY, et al. (2017) The Role of Radiotherapy in Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutationpositive Patients with Oligoprogression: A Matched-cohort Analysis. Clin Oncol 29: 568-575.

- Weiss J, Kavanagh B, Deal A, Villaruz L, Stevenson J, et al. (2019) Phase II study of stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of patients with oligoprogression on erlotinib. Cancer Treat Res Commun 19: 100126.

- Georgakopoulos I, Kouloulias V, Ntoumas G, Desse D, Koukourakis I, et al. (2024) Combined use of radiotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the management of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A literature review. Crit Rev OncolHematol 204: 104520.

- McDonald F, Guckenberger M, Popat S, Faivre-Finn C, Andratschke N, et al. (2022) EP08.03-005 HALT - Targeted Therapy with or without Dose-Intensified Radiotherapy in Oligo-Progressive Disease in Oncogene Addicted Lung Tumours. J Thorac Oncol 17: S492.

- Miyawaki T, Kenmotsu H, Kodama H, Nishioka N, Miyawaki E, et al. (2021) Association between oligo-residual disease and patterns of failure during EGFR-TKI treatment in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 21: 1247.

- Sampath S, Rashdan S, Iyengar P, Mickel TA, Zhang S, et al. (2025) Osimertinib plus consolidative radiotherapy for advanced EGFR mutant non–small cell lung cancer: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. eClinicalMedicine 87: 103435.

- Peng P, Gong J, Zhang Y, Zhou S, Li Y, et al. (2023) EGFR-TKIs plus stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for stage IV Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled phase II study. Radiother Oncol 184: 109681.

- Seong H, Kim SH, Kim MH, Kim J, Eom JS (2024) Additional local therapy before disease progression for EGFR-mutated advanced lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res 3: 491-502.

- Wang X-S, Bai Y-F, Verma V, Yu R-L, Tian W, et al. (2022) Randomized Trial of First-Line Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor With or Without Radiotherapy for Synchronous Oligometastatic EGFR-Mutated NonSmall Cell Lung Cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 115: 742-748.

- Khan TM, Verbus EA, Gandhi S, Heymach JV, Hernandez JM, et al. (2022) Osimertinib, Surgery, and Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients with Stage IIIB or IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with EGFR Mutations (NORTHSTAR). Ann Surg Oncol 29: 4688-4689.

- Elamin YY, Gandhi S, Antonoff M, Gibbons D, Negrao MV, et al. (2025) LBA72 NorthStar: A phase II randomized study of osimertinib (OSI) with or without local consolidative therapy (LCT) for metastatic EGFRmutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 36: S1729.

- Kim M-Y, Oskarsson T, Acharyya S, Nguyen DX, Zhang XH-F, et al. (2009) Tumor Self-Seeding by Circulating Cancer Cells. Cell 139: 1315-1326.

- Comen E, Norton L, Massagué J (2011) Clinical implications of cancer self-seeding. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8: 369-377.

- Sun H, Li M, Huang W, Zhang J, Wei S, et al. (2025) Thoracic Radiotherapy Improves the Survival in Patients With EGFR-Mutated Oligo-Organ Metastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol 43: 412-421.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.