The Risk of Overweight/Obesity and Related Comorbidities among HIV-Positive Versus HIV-Negative Patients Attending Same Clinics the Same Time Period in Gaborone, Botswana

by Jose GaTshikuka1-3*, Shimeles Genna Hamda1,4, Matshwenyego Boitshwarelo1, Pyana Pati Patient2, Ngoyi Kashiba Zacharie Bukonda2, Kabyahura Nene Novi5, David Mukeba Kalala2, André Kabongo3, Faustin Ndjibu3

1Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

2Department of Nursing Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, National Pedagogical University, Kinshasa I, Democratic Republic of the Congo

3Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Mbujimayi, Eastern Kasai Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo

4Vision International Training & Consultancy Service/VITCS, P.O. Box 22046, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

5Department of Paediatrics and Midwifery, Faculty of Health Sciences, National Pedagogical University, Kinshasa I, Democratic Republic of the Congo

*Corresponding author: Jose Gaby Tshikuka, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana; Department of Nursing Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, National Pedagogical University, Kinshasa I, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Received Date: 29 May, 2025

Accepted Date: 06 June, 2025

Published Date: 29 October, 2025

Citation: Tshikuka JG, Hamda SG, Boitshwarelo M, Patient PP, NKZ Bukonda, et al. (2025) The Risk of Overweight/Obesity and Related Comorbidities among HIV-Positive Versus HIV-Negative Patients Attending Same Clinics the Same Time Period in Gaborone, Botswana. J Community Med Public Health 9: 539. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100539

Abstract

Background: Previous data showed similar overweight/obesity profiles among HIV+ versus HIV- patients. However, when looking at comorbidities commonly associated with overweight/obesity among the same patients, these profiles turned dissimilar. Therefore, rising questions to whether these comorbidities (HTN, CHD, DM) were prompted by different factors between HIV+ and HIV- patients. Answers to these questions are still missing. We sought herein to: (i) compare risks of overweight/obesity among HIV+ versus HIV- patients attending same clinics, (ii) compare risks of comorbidities associated with overweight/obesity among HIV+ versus HIV- patients.

Methods: Data were collected from 287 HIV+ and 294 HIV- patients in outpatient departments of 4 general clinics in Gaborone. Two multivariate logistic models investigated covariates that explained overweight/obesity among HIV+ versus HIV- patients and two others investigated covariates explaining comorbidities among HIV+ versus HIV- patients. Covariates investigated included patients’ sociodemographic, cultural, biomedical, lifestyle and ART components. Results: Of patients investigated, both: overweight/ obese HIV+ (287 or 48.36%) and HIV- (294 or 51.63%) patients shared similar predictive covariates with same magnitude. Aside from age group that entered both: HIV+ and HIV- morbidity models, remaining covariates entered either HIV+ or HIV- sub-model. Conclusion: While outcomes from this study reveal that variabilities of overweight/obesity from both HIV+ and HIV- patients were explained by similar predictive covariates of similar magnitude; comorbidities associated with overweight/obesity among HIV+ versus HIV- patients, did not share any other covariate aside from age group. These, had different magnitude: some were predictive while others protective; therefore, the need for tailor made control programs.

Keywords: Overweight/obesity; Comorbidities; HIV+; HIV-; ART

Abbreviations: AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; ART: Antiretroviral Therapy; AZT: Azidothymidine, also known as zidovudine; BMI: Body Mass Index; CD4: Cluster of Differentiation 4; CI: Confidence Interval; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; CHD: Coronary Heart Disease; HTN: Hypertension; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IDCC: Infectious Diseases Control Centre; ICD-10: the 10th revision of the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems; MOHW: Ministry of Health and Wellness; PLHIV: People living with HIV; SD: Standard Deviation; STH: Somatotropin Hormone; WHO: World Health Organization

Background

The risk of overweight/obesity has increased globally particularly in developing countries over the last two decades. Some experts have attributed that to the rapid urbanization [1] that has taken away families from homemade to higher calorie diet in fast-food restaurants. Likewise, urbanization has reduced sedentary lifestyle, forcing people to eat anything anywhere while on the move and thus, promoting jumble eating habit with all the consequences that comes with it, i.e., risks of overweight/obesity and related comorbidities [1-3]. However, the key to the baffling epidemics of overweight/obesity and related comorbidities cannot be so simplistic. Looking at existing diversification in sociodemographic, economic, cultural and biomedical factors amongst individuals and communities, as well as the positive/negative effects of each of such factors, there is a pressing need to address these issues. Highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) drugs, such as protease and integrase inhibitors, i.e., dolutegravir, and NRTI, particularly tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) have been pointed out liable for overweight/obesity and for related comorbidities among HAART recipients [4,5]. Indeed, since the advent of ART, new profile of people living with HIV (PLHIV) has emerged. Reason why, PLHIV formally characterized by wasting syndrome [6], are now subjugated by overweight/obesity [7,8]. Though experts have reported comparable risks of overweight/obesity as well as associated comorbidities among ART recipients versus general population [9], questions of comparability of risk magnitude in developing these undesirable health events among ART-recipients versus, non-recipients, still remains ill understood.

Studies conducted in Botswana estimated the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the country to be 41% [8]. With an adult HIV prevalence of 20.3%, Botswana ranks the fourth in the world amongst the countries most affected by HIV/AIDS, leaving behind only South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho [10]; this clearly pinpoint PLHIV as a non-negligible subpopulation. Therefore, the need for equitable and prompt attention; since ± 84% of this subgroup, is on ART [10]. Hence, it is not uncommon to see higher level of overweight/obesity and related comorbidities among PLHIV compared to the general population. Works disapproving this observation seem to be limited; nevertheless, a recent report from four Gaborone general clinics showed comparable rates of overweight/obesity between HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients; paradoxically in the same report, rates of comorbidities were higher among HIV-negative compared to HIV-positive patients [11]; an unexpected situation from the authors. Since, to date no such data has been reported in the country. Nonetheless, in the neighboring South Africa this situation was already seen before. Madogoro and colleagues investigated 11,083 households during the South African national demographic health survey in 2016 [12], they reported lower prevalence of hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM) or Coronary Heart Diseases (CHD) among HIV-positive patients with overweight/obesity compared to HIVnegative patients with overweight/obesity. Likewise, Tripathi et al [13] studied 6816 HIV-positive patients; over 80% of them on ART had lower DM incidence rates than HIV-negative patients (11.4 vs 13.6). These unexpected results in fact reflect a complex interplay among factors within individuals and/or communities, example overweight/obese-HIV-positive patients and related comorbidities versus overweight/obese-HIV-negative patients and related comorbidities. The need to systematically delineate interplaying factors within and/or between different components leading to expected/unexpected outcomes is immense in order to alleviate existing controversies for an unequivocal base for decision making.

Thus, we sought in this study to: (i) identify and compare risk factors of overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIVnegative patients attending same general clinics the same time period and, (ii) compare risk factors of comorbidities commonly associated with overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients by magnitude and direction, (that is whether they have predictive or protective effect).

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study using analytical approaches to address the study objectives.

Study site and settings

The study was conducted in Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana. Its population was estimated to be 233,135 (12%) based on the 2011 Botswana Population and Housing census.

The study was conducted in 4 different Gaborone clinics: Julia Molefe clinic, BH3 clinic, Extension 2 clinic and Gaborone West clinic as they serve the highest number of patients per day compared to all other clinics. All the clinics in Gaborone have an outpatient department (OPD) and Infectious Diseases Control Centre (IDCC) where HIV positive clients follow up for treatment and routine monitoring, IDCCs are linked online through an Integrated Patient Management System (IPMS), while general outpatient clinics have either a standalone network installed or Patient Information Management System (PIMS).

Study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria

HIV-positive and HIV-negative-participants attending local health facilities between June and July 2019 in Gaborone was the study population. Outpatient clients aged 18 years and above, non-HIV patients, HIV-patients receiving ART even for pre/post-exposure prophylaxis, or as therapy for any other disease, i.e. chronic hepatitis B virus infection, as well as HIV-positive patients not yet on ART, all met the inclusion criteria. Excluded from the study were patients below 18 years of age, patients of unknown HIV status, pregnant women and women attending clinics for a 6 weeks post-natal visit, patients that were not mobile or were wheelchair bound, not capable of standing without support and patients with decreased mental capacity.

Sample size and Sampling strategy

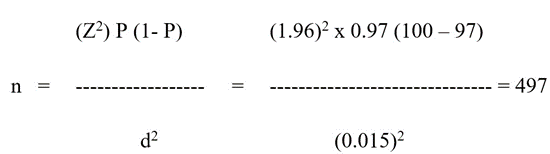

The sample size was estimated as described by Ariya and colleagues [14], using 1.96 (Z-score) as the value of the standard normal distribution corresponding to a level of alpha that was significant (<0.05) for a two-side test or margin of error of 5%; where n is the sample size, P = the expected prevalence, d = the allowable error.

Assuming that P and d, are decimal values but would hold correct if they are percentages, except that the term (1-P) will become 100-P in the numerator. P was set to 0.97 for common conditions, and d = 0.015; thus, we estimated the sample size as:

Considering respondents who will not meet inclusion criteria or withdraw from the study, this sample was increased by 17% to be 581 patients.

Selection and enrolment of both HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients were conducted in selected sites where both HIVnegative and HIV-positive were attending. Since the majorities of patients were drop-ins and did not have doctors’ appointments, it was difficult to produce a sampling frame from which potential participants could have been drawn. Nevertheless, using a systematic, every 3rd patient was selected and approached when he/she finished with his/her clinic visit of the day. Those who consented were enrolled in the study. In case of non-consent, the latter was automatically replaced by the next patient. Recruitment continued until the estimated sample size was reached. The number of patients recruited in each of the four settings was proportional to the size of patients that the clinic catered for. The study was conducted in all four clinics at the same time period.

Data collection

Data was collected by trained data collectors using a pre-tested data collection tool between, June 15 and July 31, 2019.

Data analysis

Data was analysed using IBM SPSS version 27 (Chicago, IL). Patients’ BMI were estimated as presented by Tshikuka et al., [12]; the same population was used in the current study but this time not to study the prevalence but to investigate whether what prompted outcomes were different/same between the 2 study groups and pointed to the same direction with the same magnitude. Thus, the primary outcome of the study was overweight/obesity and the secondary outcome was comorbidity (comorbidities: HTN, DM and CHD). Being HIV-positive on ART and HIV-negative were the main exposure variables. Other exposure variables are provided in Tables 1-3.

For simplicity of analysis, overweight and obesity were aggregated as a single variable “overweight/obesity”; likewise, HTN, DM and CHD were aggregated as “comorbidity”. We estimated the duration of exposure to ART among HIV-positive patients by subtracting the date of ART initiation from the date of data collection expressed in years. We used major mode of commuting as the indicator of socioeconomic status (SES) [11]. Thus, participants whose major mode of commuting was walking were considered as having a low socioeconomic status (LSES), those who used public transportation had a middle-income socioeconomic status (MSES) and those who used private cars as mode of transportation were categorized as having a high socioeconomic status (HSES). Patients with HIV/AIDS and comorbidities were identified based on the attending physician diagnosis and in line with International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10). The risk of overweight/obesity and of comorbidity was estimated using odds ratio as a proxy. To identify and compare the risk of overweight/ obesity between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, potential exposure factors were investigated in series of bivariate analyses using simultaneously overweight/obesity and comorbidity as dependent variables. Unadjusted odds ratios (UOR) and their 95% CI were estimated for each covariate. Those that achieved UOR with a p ≤ 0.90 were further investigated in multivariate logistic sub-models.

Four logistic regression models were run, two examined the risk of overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients and, two other explored the risk of comorbidity (this is because overweight/obesity and comorbidities associated to them may be prompted by different factors) among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients using the following as independent factors: (i) patients’ sociodemographic, economic and cultural factors, (ii) patient and parent biomedical factors and, (iii) patient lifestyle related factors or type of activities practiced. The model-A included only HIV-positive-patients or ART recipients; overweight/obesity was the model-A dependent variable. Independent variables were: the duration of exposure to ART, expressed as a continued variable in years and as categorical variable inclosing patients exposed to ART for >4 years and, patients exposed to ART for ≤ 4 years. Other independent variables are as presented in Tables 1-3. Model-B included only HIV-negative-patients or those who never been exposed to ART, the dependent variable was “overweight/ obesity”. Independent variables were as presented in Tables 1-3, while omitting the duration of exposure, as none of the patients directly/indirectly was on ART. Model-C included only HIVpositive patients; likewise, model-D included only HIV-negative patients. Both models had Comorbidity as dependent variable. Independent variables were as presented in Tables 1-3.

From each model, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were computed. Using backward elimination, variables kept in the models were considered as having independent effects on overweight/obesity when they achieved p <0.05 or if they had established recognition within the relationship under study; how well the models fitted the data was estimated using Cox and Snell R2 tests. Similarity between model-A (for HIV-positive) and model-B (for HIV-negativepatients) was established when the two models shared the same covariates independently of their contribution to the outcome of interest. A covariate was considered to have a predictive effect on the outcome when it had a positive β and a non-decimal 95% CI; it had a protective effect on the outcome when it had a negative β and a decimal 95% CI. The magnitude of covariate effects on the outcome, was function of the size of the AOR at p <0.05.

Results

Of the 581 participants enrolled in the study, 294 (51.63%) were

HIV negative and 287 (48.36%) were HIV positive. Of those, 136 (47.4 %) were on first line ART regimen (TDF-FTC-EFV), 61 (21.3%) were on second line (TDF-3TC-DTG), 44 (15.3%) on third line ART regimen (TDF-FTC-DTG) and 46 (16.0%) on other ART combinations. More details on HIV positive patients by ART regimen are described in Tshikuka et al [11]; Thirty-nine (7,0%) of the participants were underweight, two hundred seventy-three 273 (47%) had normal BMI. Hundred and ten patients, 110 (18.9%) were obese and 269 (46%) were overweight/obese.

Details on overweight/obesity by sociodemographic, economic and cultural factors as well as by biomedical and physical activities among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients are provided in Table 1-3.

The bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by sociodemographic and cultural factors revealed that of all examined covariate, only SES did not meet our arbitrary requirement of (¥P ≤ 0.90) for re-evaluation in multivariate models. But given the established association of SES with overweight/obesity and other health conditions it was kept for multivariate analysis. More details are provided in Table 1.

|

Dependent variable: Overweight/obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) |

||||||

|

Covariate |

HIV Positive (n=287) |

HIV Negative (n=294) |

||||

|

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

|

|

Age in years |

1.03 |

1.01 - 1.05 |

0.012* |

1.06 |

1.03 – 1.09 |

0.001* |

|

Age groups |

||||||

|

18 – 24 Years |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

25 – 34 years |

1.82 |

0.67 - 4.91 |

0.238© |

1.77 |

0.94 – 3.36 |

0.079¥ |

|

35 -44 years |

2.73 |

1.04 - 7.21 |

0.042* |

4.72 |

2.18 – 10.22 |

0.001* |

|

>45 years |

2.90 |

1.08 – 7.79 |

0.034* |

3.47 |

1.48 – 8.12 |

0.004* |

|

Gender |

||||||

|

Male |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Female |

3.61 |

2.17 – 6.00 |

<0.001* |

3.86 |

2.35 – 6.33 |

0.001* |

|

Marital Status |

||||||

|

Single |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Married |

1.32 |

0.68 – 2.57 |

0.414© |

1.92 |

0.87- 4.22 |

0.104© |

|

Area of residence |

||||||

|

Rural |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Semi Urban |

2.18 |

0.92 – 5.22 |

0.080¥ |

1.29 |

0.43 – 3.88 |

0.652© |

|

Urban |

1.14 |

0.57 – 2.29 |

0.710© |

1.77 |

0.65 – 44.82 |

0.267© |

|

Education |

||||||

|

Tertiary |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Secondary |

1.73 |

0.81 – 3.70 |

0.155© |

1.05 |

0.64 – 1.70 |

0.857© |

|

Primary |

1.44 |

0.78 – 2.63 |

0.237© |

3.57 |

1.18 – 10.81 |

0.024* |

|

Socioeconomic status |

||||||

|

High SES |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Midclass SES |

1.32 |

0.71 – 2.48 |

0.932© |

1.87 |

0.98 – 3.56 |

0.057¥ |

|

Low SES |

0.97 |

0.51 – 1.86 |

0.379© |

1.06 |

0.62 – 1.82 |

0.823© |

|

Cultural, Religion |

||||||

|

Christianity |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

ATR & Other |

1.16 |

0.51 – 2.60 |

0.638© |

1.79 |

0.72 – 4.48 |

0.212© |

|

None |

0.93 |

0.30 – 2.08 |

0.724 |

1.79 |

0.72 – 4.48 |

0.212© |

|

Legend: BMI: Body Mass Index, CI: Confidence Interval, HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, SES: Socioeconomic Status, UOR: Unadjusted Odds ratios, *p<0.05, ¥P: borderline p: ©p ≤0.90: arbitrary p value for further investigation in multivariate sub-models, ATR & Other: association of traditional religions. |

||||||

Table 1: Bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by sociodemographic, economic and cultural factors among HIV-positive versus HIVnegative patients attending general clinics in Gaborone, Botswana in 2019.

Bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by biomedical factors revealed that HIV-positive patients whose parents had HTN were more likely (p<0.05) to be overweight/obese compared to those whose parents were free of HTN. Similarly, HIV-negative patients whose parents had HTN were more likely to be overweight/obese compared to HIV-negative whose parents did not have HTN. HIV-negative patients who had HTN were more likely (p<0.05) to be overweight/obese compared HIV-negative patient free of HTN. HIV-negative patients who were free of HTN were not associated with overweight/obesity. More details are given bellow in Table 2.

|

Dependent variable: Overweight/obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) |

||||||

|

Covariate |

HIV-Positive (n=287) |

HIV-Negative (n=294) |

||||

|

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

|

|

Reason of clinic visit |

||||||

|

Follow Up |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Sick Visit |

1.08 |

0.47-2.44 |

0.863© |

0.63 |

0.36-1.08 |

0.096© |

|

Other |

- |

- |

- |

0.55 |

0.24 – 1.23 |

0.146© |

|

Types of ART |

||||||

|

2NRTIs + NNRTI |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

||

|

2NRTIs + II |

1.66 |

1.02-2.71 |

0.042* |

- |

- |

|

|

2NNRTIs + PI |

0.67 |

0.19-2.39 |

0.541© |

|||

|

Duration on ART in years |

||||||

|

More than 4 years |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

≤ 4 years |

1.68 |

1.05-2.68 |

0.029* |

- |

- |

- |

|

Parent with HTN |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.77 |

1.06-2.98 |

0.030* |

1.64 |

1.01 – 2.67 |

0.046* |

|

Parent with DM |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Yes |

1.35 |

0.55-3.32 |

0.508© |

0.72 |

0.33 – 1.56 |

0.401© |

|

Parent with CHD |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

0.49 |

0.44-5.50 |

0.508© |

0.90 |

0.12 – 5.47 |

0.909 |

|

Patient has comorbidity |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

|

|

HTN |

3.12 |

0.32-30.34 |

0.328© |

11.88 |

3.54 – 39.93 |

0.001* |

|

DM/CHD |

1.63 |

0.61-4.34 |

0.326© |

1.36 |

0.62 – 3.01 |

0.444 |

|

HTN+DM+CHD |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

|

Yes |

0.96 |

0.76-1.23 |

0.76© |

0.62 |

0.48-0.81 |

0.001* |

|

Legend: HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, BMI: Body Mass Index, CHD: Coronary Heart Disease, HTN: Hypertension, UOR: Unadjusted Odds ratios, CI: confidence interval, *P<0.05: level of significance, ©p ≤0.90: arbitrary value for further investigation in multivariate sub-models, SES: Socioeconomic status, ART: Antiretroviral Therapy, II: Integrase Inhibitor (Dolutegravir), NNRTIs: Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor (Nevirapine & Efavirenz), NRTIs: Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (a combination of either ABC or AZT with 3TC and TDF with FTC), PI: Protease Inhibitor (Lopinavir/ritonavir). |

||||||

Table 2: Bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by biomedical factors among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients attending general clinics in Gaborone, Botswana in 2019.

Bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by life style habits in Table-3 showed that smoking was strongly associated (P<0.05) with overweight/obesity for both HIV-positive and negative patients while lifestyle factor was significantly associated with overweight/ obesity among HIV-negatives patients. More details are provided bellow in Table 3.

|

Dependent variable: Overweight/obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) |

||||||

|

Covariate |

HIV-Positive (n = 287) |

HIV-Negative (n = 294) |

||||

|

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

UOR |

95% CI |

P |

|

|

Physical activities |

||||||

|

Yes |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

No |

1.41 |

0.88 – 2.28 |

0.157© |

2.42 |

1.37 – 4.29 |

0.002* |

|

Smoking status |

||||||

|

Never |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Ex-Smoker |

0.93 |

0.42 - 2.06 |

0.850© |

0.77 |

0.39 - 1.52 |

0.446© |

|

Smoker |

0.30 |

0.13 - 0.66 |

0.003* |

0.32 |

0.12 – 0.72 |

0.006* |

|

Alcohol Consumption |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Yes |

1.27 |

0.80 – 2.02 |

0.317¥ |

1.02 |

0.64 – 1.64 |

0.923 |

|

Legend: BMI: Body Mass Index, UOR: Unadjusted Odds ratios, CI: Confidence Interval, HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus, *p<0.05, ©p≤0.90: arbitrary p value for further investigation in multivariate sub-models. |

||||||

Table 3: Bivariate analysis of overweight/obesity by life style habits among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients attending general clinics in Gaborone, Botswana in 2019.

The risks of overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients attending outpatient department of general clinics in Gaborone are provided in Table 4. (i) Results indicate that the covariate gender entered with significance (p<0.05) in both sub-model A and B; female HIV-positive patients were 5.12 (AOR: 5.12, 95% CI:2.73-9.85) times more at risk of overweight/ obesity than their counterparts HIV-positive male in Sub-model A; likewise, in model B female HIV-negative patients had 4.15 (AOR: 4.15, 95% CI: 2.30-7.48) times more risk of overweight/ obesity compared to their male counterparts ; (ii) aside from HIVpositive patients aged 25-34, the rest of age groups entered both model A and B with significance (p<0.05), HIV-positive patients aged 35-44 and those aged ≥ 45 years old had respectively 4.0 (AOR: 4, 95% CI:1.31 – 12.21), and 5.42 (AOR: 5.42, 95% CI:

1.69-17.40) times the risk of overweight/obesity compared to HIV-positive patients aged 18-24 years; model B, HIV-negativepatients aged 25 to 34, 35 to 44 years and those aged ≥ 45 years old were respectively 2.38, (AOR: 2.38, 95% CI: 1.16-4.88), 5.18 (AOR: 5.18, 95% CI: 2.07-12.95) and 3.19 (AOR: 3.19, 95% CI:

1.10-9.21) times at risk of overweight/obesity compared to those aged 18-24 years. (iii) Alcohol consumption is strongly associated with overweight/obesity in both models; HIV-positive patients had

1.78 (AOR:1.78, CI: 0.98-3.23) and, HIV-negative patients had 1.79 (AOR:1.79, CI: 1.01-1.31) the risk of overweight/obesity compared to non-alcohol drinkers, HIV-positive-patients residing in semi-urban area had 3.10 (AOR: 3.10, 95% CI: 1.17 – 8.21) times the risk of overweight/obesity compared to those who resided in the rural area, more details are in Table 4; (iv) Patients with parental history of HTN, entered the model-A for HIV-positive with significance (p<0.05); they had 1.85 (AOR: 1.85, 95%, CI: 1.03 – 3.34,) more the risk of overweight/obesity compared to HIV-positive patients with no parental history of HTN; patients with HTN had 3.67 (AOR: 3,67, 95% CI: 1.18-11.42) more risk of being overweight/obese compared to HIV-negative patients with no HTN; patients with other types of comorbidities in model-A for HIV-positive and for the model-B for HIV-negative respectively did not contribute to the outcome of interest. (vi); in model-B, HIV-negative patients who did not practiced physical activities had 1.97 (AOR: 1.97, 95% CI: 1.04-3.74) times more risk of being overweight/obese compared to those who practiced physical

activities, (ix) in model-A, HIV-positive patients exposed to ART for ≤4 years had 2.50 (AOR: 2.50, 95% CI: 1.45 – 4.31) times more risk of being overweight/obesity compared HIV-positive exposed to ART for >4 years (Table 4).

|

Dependent variable: Overweight/obesity |

||||||

|

Correlate |

model-A: HIV Positive (n =287) |

model-B: HIV Negative (n = 294) |

||||

|

AOR |

95% CI |

P |

AOR |

95% CI |

P |

|

|

Gender |

||||||

|

Female, n (%) |

5.12 |

2.73 – 9.85 |

<0.001* |

4.15 |

2.30 – 7.48 |

0.001* |

|

Age groups |

||||||

|

18 – 24 Years |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

25 – 34 years |

1.58 |

0.52 – 4.81 |

0.420 |

2.38 |

1.16 – 4.88 |

0.018* |

|

35 -44 years |

4.00 |

1.31 – 12.21 |

0.015* |

5.18 |

2.07 – 12.95 |

0.001* |

|

≥45 years |

5.42 |

1.69 – 17.40 |

0.004* |

3.19 |

1.10 – 9.21 |

0.032* |

|

Area of residence |

||||||

|

Rural |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

Semi Urban |

3.10 |

1.17 – 8.21 |

0.023* |

1.51 |

0.40 – 5.65 |

0.541 |

|

Urban |

1.11 |

0.52 – 2.39 |

0.788 |

2.01 |

0.60 – 6.69 |

0.253 |

|

Parent with HTN |

||||||

|

Yes |

1.85 |

1.03 – 3.34 |

0.040* |

1.40 |

0.79 – 2.48 |

0.249 |

|

Patient with comorbidity |

||||||

|

No |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

||

|

HTN |

1.45 |

0.46 – 4.59 |

0.526 |

3.67 |

1.18 – 11.42 |

0.025* |

|

Others |

3.27 |

0.27 – 39.90 |

0.354 |

0.65 |

0.27 – 1.57 |

0.346 |

|

Physical activities |

||||||

|

No |

1.16 |

0.67 – 2.01 |

0.589 |

1.97 |

1.04 – 3.74 |

0.039* |

|

Smoking |

||||||

|

Yes |

0.43 |

0.17 – 1.09 |

0.074¥ |

0.51 |

0.20 – 1.31 |

0.164 |

|

Consume Alcohol |

||||||

|

Yes |

1.78 |

0.98 – 3.23 |

0.058¥ |

1.79 |

1.01 – 2.31 |

0.047* |

|

Duration on ART in years |

||||||

|

Above 4 years |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

≤ 4 years |

2.50 |

1.45 – 4.31 |

0.001* |

- |

- |

- |

|

Legend: AOR: Adjusted Odds ratios, ART: Antiretroviral Therapy, CI: Confidence Interval, HTN: Hypertension, BMI: Body Mass Index, *P<0.05; ¥P: borderline significance [15]. |

||||||

Table 4: Adjusted correlates of overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV negative patients attending clinics in Gaborone, Botswana in 2019.

The risk of comorbidity (HTN+DM+CHD) among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients attending same outpatient department of general clinics in Gaborone are presented in Table 5 model-C: (i) HIV-positive-patients aged ≤ 45 years old had 34% (AOR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.14-0.62) less risk of having comorbidities compared to HIV-positive patients aged > 45 years old; yet in Sub-model D, HIVnegative patients aged ≤ 45 years had only 12% (AOR; 0.12, 95% CI: 0.07 – 0.19) less risk of having comorbidity compared to patients aged > 45 years. (ii) in model C, gender among HIV-positive patients did not enter in the other; while in the model-D, females (AOR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.055-3.193) were 84% more at risk of comorbidity compared to male HIV-negative patients ; (iii) Overweight/obese HIV-positive-patients had 29% (AOR: 1.29,95% CI: 1.14-1.62) more risk of developing comorbidity compared to HIV-positive-patients who were not overweight/obese; This covariate did not enter the model-C for HIV-negative patients; (iv) in the model-C HIV-positive patients who practiced physical activities had 36% (AOR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.13-0.044) less risk of having comorbidity than HIV-positive patients who did not practice physical activity. More details in this covariate is in Table 4 model D (v) HIV-positive patients who smoked had 34% (AOR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.17- 0.66) less risk of having comorbidity compared to HIV-positive patients who were not smokers; again, more details on this covariate and the rest are in Table 4.

|

Dependent variable: Comorbidity (HTN+DM+CHD) |

||||||

|

Correlate |

model-C: HIV-Positive (n =287) |

model-D: HIV-Negative (n = 294) |

||||

|

AOR |

95% CI |

P |

AOR |

95% CI |

P |

|

|

Age groups |

||||||

|

>45 Years old |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

|

≤45 years old |

0.34 |

0.14-0.81 |

0.015* |

0.12 |

0.070-0.193 |

0.001* |

|

Parent with HTN |

||||||

|

Yes |

0.29 |

0.14-0.62 |

0.001* |

- |

- |

- |

|

Physical activities |

||||||

|

Yes |

0.36 |

0.13-0.97 |

0.044* |

- |

- |

- |

|

Smoking |

||||||

|

Yes |

0.34 |

0.17-0.66 |

0.001* |

- |

- |

- |

|

Gender |

||||||

|

Female |

- |

- |

- |

1.84 |

1.058-3.193 |

0.031* |

|

Quality of food consumed |

||||||

|

Junk food |

- |

- |

- |

1.510 |

0.698-3.263 |

0.295¥ |

|

Legend: AOR: Adjusted Odds ratios, ART: Antiretroviral Therapy, CI: Confidence Interval, HTN: Hypertension, BMI: Body Mass Index, *P<0.05; ¥P: borderline significance |

||||||

Table 5: Adjusted correlates of Comorbidity (HTN+DM+CHD) among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients attending clinics in Gaborone, Botswana in 2019.

Discussion

The current epidemic of overweight/obesity among ART recipients has prompted polemics among scientists as indicated herein by the number of conflicting reports [9, 11-13,16-21]. Some experts claiming the epidemic as an aftermath of ART [17-20] while others are maintaining that it is part of the current overweight/obesity epidemic in the general population [11, 15]. On the other-hand there is literature that even pinpoint specific ARTs, i.e., protease [15] and integrase inhibitors [18,22-24], as factors explaining most variabilities of overweight/obesity among the recipients. A narrative review of critical appraisal of articles published until year 2024 in the field, by Konstatinos Markakis and colleagues [25] indicate challenges of assessing the role of HAART on weight gain as an interplay of different factors needing cautious investigation.

Weight gain, for example, depends on the stage of HIV and preART profiles of the patients or changes in the composition of gut microbiota [25]. Weight gain may reflect immune reconstitution in patients with advanced disease and are linked with increased CHD and DM among those who are obese. ART associated with significant weight gain promotes the fibrosis of adipose tissue and the accumulation of lipids in adipocytes, one of the mechanisms mentioned for weight gain among patients on HAART [24]. In addition, factors such as sociodemographic, SES [26], biomedical, nutritional and cultural [8, 21] are also incriminated as potential risk factors thus, so far continue to cloud trustworthy sources of overweight/obesity among PLHIV.

The present study brings in some new insights to global efforts to alleviate disparities around ART, overweight/obesity and related comorbidities. Exposure to HAARTs, as risk factors of overweight/ obesity and, related comorbidities have been investigated among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients attending same clinics at the same time period to exclude site and time effects. Findings were eye-catching; all significant covariates that entered submodel A for HIV-positive were identical to those that entered submodel B for HIV-negative patients (ART naïve patients). Within HIV-positive or model A, patients exposed to ART for ≤ 4 years were more at risk of overweight/obesity than those exposed for > 4 years which, somewhat was contradictory to our expectations. But, the rest of covariates were generally similar in both, models. Aside from the duration of exposure to ART in model-B which had no meaning due to lack of exposure to ART, the rest of covariates had predictive effects on the outcome with comparable magnitude. For example, HIV-positive females’ patients in model-A were 5.12 times more at risk of overweight/obesity compared to HIVpositive males. Similarly, HIV-negative-females in model-B were 4.15 times more at risk of overweight/obesity than HIV-negative males. Also, in model-A HIV-positive patients aged between 35-44 years old were more at risk than HIV-positive patients aged 18-24; and so were HIV-negative patients aged 35-44 years old compared HIV-negative patients aged 18-24 years old. These results are in lines with overweight/obesity observed among HIV-positive patients as they do not differ from those of the current epidemic in the general population [9]; because factors explaining variability of the outcome among HIV-positive patients in model-A, are just those explaining overweight/obesity in the model-B among HIVnegative patients yet, the latter were not on ART. Suggesting that had ART been the major causal factor of overweight/obesity, the recipients in the Sub-model A would have been much overweight/ obese compared to non-ART recipients in model B; but this wasn’t the case here. Also, the fact that effect of covariates in both models were predictive with similar magnitude, only plead for similarity between model A and B. Although in both model-A and -B, effects of age groups on overweight/obesity generally shrunk with age, the magnitude of the drop only showed trivial gaps between model-A and -B.

The absence of exposure to ART among HIV-negative patients should have resulted in normal BMI in model-B, or significantly lower the risk of the outcome, rather than yielding comparable risk with HIV-positive in model-A. Since, this was not the case, data presented here could only lend support to claims that overweight/ obesity seen among ART-recipients was part of the current epidemic in the general population [9]. Also, the fact that previous studies failed to find differences in outcomes from patients exposed to different ART regimens and durations [24] only strengthen this claim. On HIV-positive patients exposed to ART for ≤ 4 years being at risk of the outcome more than those exposed for >4 years, the profile may need further studies for clarification. Since ART per se, did not itself entered the parsimonious model A, its absence in these predictive models may be an indication of lack of direct effect on the outcome. There are reports that ART contributes only in the restoration of HIV-positive patients’ health status through suppression of viral replication resulting to normal level of CD4 [27]; hence, exposing both: HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients (the general population) to same health insults such as overweight/obesity, opportunistic infections, etc. Nevertheless, while these appear to be in line with claims that overweight/ obesity among HIV-positive patients is actually part of the current epidemic in general population, associated comorbidities are not necessarily so.

Since, models for comorbidity in this study have profiles not compatible to those of overweight/obesity. Results for comorbidity in model-C and -D differed in profiles and covariates from those in model-A and -B for overweight/obesity. Risk factors of comorbidity among HIV-positive patients in model C for HIV-positive patients are not the same and significantly differ in magnitude and direction of effect from those in model-D for HIV-negative patients. Even though reports of higher rates of HTN, CHD and DM among HIVpositive compared to HIV-negative patients abound the literature [23,24]. Ironically, findings herein do not corroborate these observations [23,24]; which, therefore, support data presented herein. We have documented in this study that HTN and DM/ CHD were less prevalent among HIV-positive compared to HIVnegative patients. At the first glimpse, it is hard to believe that HIV-negative patients to have higher level of morbidity compared to HIV-positive patients due to difference in immune systems. But the literature lends strong support to these results. Works by Madogoro and colleagues in the neighboring South Africa support our findings with no reservation [12]. The authors investigated 11,083 households during the South African national demographic health survey in 2016 and reported lower rates of HTN, DM or CHD among HIV-positive overweight/obesity among adult South Africans compared to HIV-negative patients. Likewise, Tripathi et al [13] studied 6816 HIV-positive patients; over 80% of them on ART had lower DM incidence rates than HIV-negative patients (11.4 vs 13.6). Also, Alsaeed, et.al, [28] reported a lower incidence of DM in obese PLHIV compared to their counterparts in the general population.

These reports are amenable to speculations that: (i) ART might have factors helping develop some protective mechanisms against HTN, DM, or DM/CHD in HIV-positive patients (ii) overweight/ obesity might have the capacity to induce HTN, DM and DM/ CHD in patients irrespective of their HIV status; (iii) the host, HIV+/HIV- might be harboring factors arising from changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-STH axes leading to overweight/ Obesity or associated to others outcomes i.e., hyperinsulinemia. Tshikuka and Torres-angel [6], investigated wasting syndrome in animal model through hypothalamic-pituitary-thymus axe using intracranial inoculation of distil water to control and feline Leukemia/AIDS virus to experimental animals. The animals wasted and died weeks later but, two of them survived. They plateaued, gained weight and eventually became overweight compared to their control counterparts; suggesting that the outcome was function of a complex interplay of factors. In another reports, Das et al.[29], after conducting a systematic review of association between malnutrition and malaria, they described the predictive effect of malnutrition on malaria, paradoxically they also described the protective effect of extreme malnutrition against malaria [29, 30], These observations are indicative of complex relationships from interplays of drug factors, agent factors and the host factors as well as the capacity of each of those to change the normal course of health events (morbidity). More researches are certainly warranted at both, molecular and field levels to address these enigmatic outcomes in order to settle existing conflict and help to inform decision. The lower risk of DM and HTN among HIV-positive patients on ART compared to HIV-negative (ART naïve) patients reported herein likely results from the interplay of these multitude factors. Many of which might belong to the current highly active ART (HAART) combinations, genetic, coexisting pathologies, etc. Indeed, HAART have been reported as having fewer adverse effects as demonstrated by data from the South Carolina Medicaid system and the enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System Surveillance Database [30]. These studies [30] showed little difference in DM incidence between HIV-positive and HIVnegative patients from 1994 to 2003. But, from 2004 through 2011 when HAART took over as the first-line regimen, results showed significantly lower DM incidence among HIV-positive patients compared to HIV-negative; suggesting that studies aiming to control overweight/obesity and related comorbidity (HTN, DM or DM/CHD) among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients should not only focus on approaches used in the general population.

Strategies considering factors of ART, HIV and the host are probably approaches leading to effective control of overweight/ obesity as well as related comorbidity and thus promoting health care for everyone and not for specific disease care. The complexity of factors that explained variability of overweight/obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients brought up question to whether comorbidities commonly associated with overweight/ obesity among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative had similar covariates with comparable magnitude and effect.

While outcomes from this study reveal that variabilities of overweight/obesity from both ART recipients and HIV-negative patients were explained by similar covariates, of similar predictive effects and magnitude; this profile, changed when looking at comorbidities presumably associated with overweight/obesity among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. Aside from age group the two models did not share any other covariate, they had covariates with different magnitude; some were predictive while others were protective. Smoking for example had protective effect among HIV-positive patients on ART. This was indeed an effect modification of baseline bivariate data due to interplay of multiple factors, such as those fitting to ART, HIV and specific hosts.

Studies aiming to control overweight/obesity and related comorbidity (HTN, DM or DM/CHD) among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients should not only focus on approaches used in the general population. Tailor made strategies considering factors of ART, HIV and the host might be considered for an effective control of overweight/obesity as well as related comorbidity.

Study Limitations

The absence of HIV-positive patient subgroup not on ART and, the use of a cross sectional approach to address this complex topic may stand as limitations of the study. While the use of HIV positive patients not on ART might have posed serious ethical problems, the use of a robust analytical approach, sample selection and meticulous data quality control handled the issue of a cross sectional approach well and conferred to the study an acceptable validity to inform decision making. Further studies addressing these limitations are nevertheless recommended

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data Availability

Data underlying the findings in this study are neither readily available nor publicly accessible; they are professionally managed and safeguarded to protect patient confidentiality, as they include potentially identifying demographic and clinical care information. However, the data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Before sharing the data, the latter would need first to securer clearance from the management of the HIV clinics where the study was conducted.

Funding Statement

The study Funding Institution was MSR through St. George University of London’s Phase III RIFASHORT, a multi country randomized control trial to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of high dose rifampicin at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Botswana. Amount (US $1,200,000.00), from 2017 to Dec 2019.

Authors’ Contributions

This study was designed by JG Tshikuka, M Boitshwarelo, and S Hamda. The three participated in all the stages of this study, from the preparation of the proposal to manuscript writing. NKZ Bukonda, PP Pyana, NN Kabyahura D Mukeba, A Kabongo and F Ndjibu participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation. All the authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, read and approved the final copy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Julia Molefe clinic, BH3 clinic, Extension 2 clinic and the Gaborone West clinic staff for allowing us to collect data at their facilities. We value the contribution of MGMD Magafu and ME Onokoko in reviewing the study proposal, data analyses, and writing the manuscript. Our gratitude also goes to research assistants and nurses who were instrumental in data collection. We acknowledge the scientific input from Dr Lesego Gabaitiri and thank all the respondents who consented to participate in the study.

References

- Hossain MB, Khan JR, Adhikary AC, Mehbub Anwar AHM, Raheem E, et al. (2022) Association between childhood overweight/obesity and urbanization in developing countries: evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Public Health 30: 2819-2828.

- Pirgon O, Alsan N (2015) The Role of Urbanization in Childhood Obesity. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 7: 163-167.

- Salgodo Conseco MJ (2019) Urban Development and Human Health. Good health and wellbeing 759 - 767. Encyclopedia of the United Nation of Sustainable Development Goal.

- Belete NK, Assefa DT, Gadore TF, Teshale MY, Tariku EZ (2023) Association between Overweight/Obesity and ART Drug regimen among Adult HIV Patients in Gamo Public Health Facilities Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 15: 349-360.

- Lake, JE, Trevillyan, J (2021) Impact of Integrase inhibitors and tenofovir alafenamide on weight gain in people with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 16: 148-151.

- Tshikuka JG, Torres-Anjel MJ, Blenden DC, Elliott SC (1992) The Microepidemiology of Wasting Syndrome, a common Link to Diarrheal Disease, Cancer, Rabies, Animal Model of AIDS, and HIV-AIDS (HAIDS). The Feline Leukemia Virus and Rabies Model. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 653: 274-296.

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration (2017) Survival of HIVpositive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 4: e349-e356.

- Keetile M, Navaneetham K, Letano G, Balname K, Rakgoasi SD, et al. (2019) Socioeconomic and behavioural determinants of overweight/ obesity among adults in Botswana: a crosssectional study. BMJ Open 9: e029570.

- Crum-Cianflone N, Tejidor R, Medina S, Barahona I, Ganesan A (2008) Obesity among patients with HIV: the latest epidemic. AIDS Patient Care STDS 22: 925-930.

- The Fifth Botswana AIDS Impact 2021 Report August 2023.

- Tshikuka JG, Boitshwarelo M, Hamda SG, Tapera R, Bukonda NKZ, et al. (2024) The Prevalence of Overweight/obesity and related comorbidities among HIV-positive and HIV-negative Patients attending the same clinics in Gaborone, Botswana. Advances in Infectious Diseases 14: 523-540.

- Magodoro IM, Okello S, Dungeni M, Castle AC, Mureyani S, et al. (2022) Association between HIV and prevalent hypertension and diabetes mellitus in South Africa. Analyses of a nationally representative crosssectional survey. Int J Infect Dis 121: 217-225.

- Tripathi A, Liesse AD, Jerrell VM, Zhang J, Rizvi AA, et al. (2014) Incidence of diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of HIVinfected and non-HIV-infected persons: the impact of clinical and therapeutic factors over time. Diabet Med 31: 1185-1193.

- Arya R, Antonisamy B, Kumar S (2012) Sample size estimation in prevalence studies. Indian J Pediatr 79: 1482-1488.

- Tshikuka JG, Magafu Mgaywa GMD, Molefi M, Masupe T, MatchabaHove RB, et al. (2016) Addressing the Challenge of P - Value and Sample Size when the Significance is Borderline: The Test of Random Duplication of Participants as a New Approach. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research 5: 214-218.

- Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L, Headd M, Marconi V, et al. (2010) Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS One 5: e10106.

- Bedimo R, Xilong L, Adams-Huet B, Lake JE, Taylor BS, et al. (2019) Differential BMI changes following PI- and InSTI-based ART initiation by sex and race. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, Abstract 675.

- Bourgi K, Jenkins CA, Rebeiro PF, Lake JE, Moore RD, et al. (2019) Greater weight gain among treatment-naïve persons starting integrase inhibitors. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, abstract 670.

- Kerchberger AM, Eng M, Sheth AN, Angert CD, Mehta CC, et al. (2019) Integrase strand transfer inhibitors are associated with weight gain in women. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, Abstract 672.

- Lake JE, Wu K, Bares SH, Debroy P, Godfrey C, et al. (2020) Risk Risk Factors for Weight Gain Following Switch to Integrase Inhibitor-Based Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin Infect Dis 71: e471-e477.

- Letamo G (2020) Dual burden of underweight and overweight/obesity among adults in Botswana: prevalence, trends and sociodemographic correlates: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 10: e038614.

- Hill A, Venter WF, Delaporte E, Sokhela S, Kouanfack C, et al. (2019) Progressive rises in weight and clinical obesity for TAF/FTC/DTGand TDF/FTC/DTG versus TDF/FTC/EFV: ADVANCE and NAMSAL trials. 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science, Mexico City, Abstract MOAX0102LB.

- Kerchberger AM, Sheth AN, Angert CD, Mehta CC, Summers NA, et al. (2020) Weight Gain Associated With Integrase Stand Transfer Inhibitor Use in Women. Clin Infect Dis 71: 593-600.

- Tshikuka JG, Rankgoane-Pono G, Damas Magafu MGM, Masupe T, Molefi M, et al. (2018) Relationship between combination antiretroviral therapy regimens and diabetes mellitus-related comorbidities among HIV patients in Gaborone, Botswana. BMC Public Health 18: 464.

- Markakis K, Tsachouridou O, Georgianou E, Pilalas D, Nanoudis S, et al. (2024) Weight Gain in HIV Adults Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Life 14: 1367.

- Hogg R, Lima V, Sterne JA, Grabar S, Battegay M, et al. (2008) Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in highincome countries: an analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 372: 293299.

- Phillips AN, Staszewski S, Weber R, Kirk O, Francioli P, et al. (2001) HIV viral load response to antiretroviral therapy according to the baseline CD4 cell count and viral load. JAMA 286: 2560-2567.

- Alsaeed AH, Aljanobe AH, Alhassan SH, Almulaify MS, AlKhalaf AA, et al. (2024) Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus in People Living with HIV in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 16: e63809.

- Das D, Grais RF, Okiro EA, Stepniewska K, Mansoor R, et al. (2018) Complex interactions between malaria and malnutrition: a systematic literature review. BMC Med 16: 186.

- Murray MJ, Murray AB, Murray NJ, Murray MB (1978) Diet and cerebral malaria: the effect of famine and refeeding. Am J Clin Nutr 31: 57-61.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.