The Minimal Impact of Additives in University of Wisconsin Solution During Organ Procurement and Cold Static Storage in Australia: Nationwide Prospective Database Analysis

by Zhong Li Titus Lim1*, Sebastian Primrose1, Eric Chung2, Jason Kim1, Angela McInnes3, Janske Reiling4, Nicholas Black5, Ai Lin Tan5, Ryan Gately6, Handoo Rhee2

1Department of Urology, Princess Alexandra Hospital. 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

2University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia, Department of Urology, Princess Alexandra Hospital

199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

3Donate Life Queensland, Organ and Tissue Donation Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

4University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia, Department of Transplant Surgery, Princess Alexandra Hospital. 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

5Department of Transplant Surgery, Princess Alexandra Hospital. 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

6Department of Nephrology and Kidney Transplantation, Princess Alexandra Hospital 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia 4102Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

2University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia, Department of Urology, Princess Alexandra Hospital, 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia 4102 Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

*Corresponding Author: Zhong Li Titus Lim, Department of Urology, Princess Alexandra Hospital. 199 Ipswich Road, Woolloongabba, Queensland, Australia

Received Date: 04 February 2026

Accepted Date: 09 February 2026

Published Date: 11 February 2026

Citation: Lim ZLT, Primrose S, Chung E, Kim J, McInnes A, et al. (2026) The Minimal Impact of Additives in University of Wisconsin Solution During Organ Procurement and Cold Static Storage in Australia: Nationwide Prospective Database Analysis. J Surg 11: 11562 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011562

Abstract

Background: The University of Wisconsin (UW) solution is the most commonly used preservation fluid for abdominal organ procurement and storage in Australia. Originally developed in the 1980s by Folker Belzer and James Southard, its initial formulation advocated the addition of antibiotics, insulin and dexamethasone to preserve abdominal organs which included the liver, kidneys and pancreas. Over the years, various jurisdictions across Australia and the world have elected not to use the additives. This study analyzes prospectively collected nationwide data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) registry to determine whether the omission of recommended additives in the UW solution, namely insulin and dexamethasone, result in any changes to the outcomes for the kidney transplant recipients.

Methods: Donor and recipient data between 2014 to 2023 were obtained from the ANZDATA national registry. Adult patients who underwent kidney transplantation during this period were included in this study. The cohort was divided into two groups according to geographical states in Australia: 1) states known to use UW solution with insulin and dexamethasone and 2) states that used UW solution alone as a routine practice. Delayed graft function, acute rejection rate and primary non-function rates were analyzed with logistic regression models. Time-to-event analyses such as time to rejection, time to graft loss were analyzed using multivariable Cox models.

Results: During the study period, 6732 patients underwent kidney transplantation in Australia. Of these, 1534 (22%) recipients received organs that did not contain additives in the UW solution. There were no significant statistical differences between these two groups in terms of baseline demographics. No statistically significance differences were observed between groups in terms of DGF, rejection or primary non-function, with odds ratio of 1.09 (95% CI: 0.94-1.27, p=0.3), 0.98 (95% CI: 0.84-1.15, p=0.8) and 1.15 (95% CI: 0.85-1.55, p=0.4) respectively. No statistical significance was noted for both groups with regards to all-cause graft loss and death-censored graft loss with a hazard ratio of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.79-1.12, p=0.5) and 1.08 (95% CI: 0.86-1.35, p=0.5) respectively.

Conclusion: In conclusion, this study does not support the routine use of insulin and dexamethasone as additives in UW solution for kidney donors. Omitting the additives may reduce procurement labour and material costs and minimize potential risks associated with the manual preparation such as contamination, without compromising transplant outcomes.

Keywords: Additives; Dexamethasone; Insulin; Kidney Transplant; University of Wisconsin Solution

Introduction

Kidney Failure (KF) is a leading cause of morbidity in Australia, affecting thousands of patients annually. In 2022, 29,000 people required renal replacement therapy, with selective patients proceeding with transplantation to improve long-term survival and quality of life. Satisfactory long term graft function following transplantation is determined by many donor factors including donor characteristics and comorbidities, donation pathways but also organ procurement and preservation methods prior to transplantation. University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, developed in the 1980s, remains the most commonly used preservation fluid for abdominal organ transplantation, both in Australia and worldwide [1,2]. Initially formulated with insulin, penicillin G, and dexamethasone, these additives were later removed to be added manually by the user, due to concerns regarding storage stability and manufacturing complexities. Many Australian centers have elected to follow the original formulae assuming potential benefits in reducing ischemia-reperfusion injury and improving graft outcomes [3].

Despite the theoretical benefits, evidence supporting the routine use of insulin and dexamethasone in UW solution remains inconclusive. While insulin was initially intended to stimulate the production of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) by glycolysis during organ storage, it may also prevent apoptosis and dampen inflammatory pathways that may trigger rejection [4]. However, paradoxically, studies in animal models suggest amplified hepatic ischaemic-reperfusion injury, and reduced ATP/energy charge/adenosine nucelotide within the graft after storage and resulted in poor graft outcomes such graft survival [5,6]. Similarly, dexamethasone has demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects that could reduce rejection and Delayed Graft Function (DGF) [7], yet its role in organ preservation remains unclear. Since the introduction of UW solution, several alternative preservation solutions, such as Celsior and Histidine-Tryptophan Ketoglutarate (HTK), have been developed without insulin or dexamethasone [8]. As transplant outcomes remain comparable across these solutions, the necessity of these additives has been called into question [9]. Currently, practices vary across Australian centers, with some continuing to use these additives while others have discontinued their use over the past decade. This study aims to take advantage of two different streams of practice in Australia and evaluate whether the addition of insulin and dexamethasone to UW solution provides any therapeutic benefit in kidney transplantation. Using prospectively collected data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) registry, we compare outcomes between centers that utilize these additives and those that do not. The findings will help determine whether maintaining this practice is justified or if simplifying preservation protocols could improve cost-effectiveness and logistical efficiency.

Methods

Study Population

All adult donor and recipient data were collected from the ANZDATA registry between 2014 and 2023. ANZDATA is a binational clinical quality registry that systematically collects data via an opt-out process, which significantly enhances the comprehensiveness of its information collection. Details regarding the method for data collection can be found at its website (http://www.anzdata.org.au). De-identified information was provided by the ANZDATA custodian team for this study to ensure that the origin of the patient information could not be found.

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years and over who had kidney transplantation between 2014 and 2023 within Australia. Exclusion criteria included en-bloc kidneys and simultaneous multi-organ transplants. The recipients' data was extracted and categorized into two groups based on whether the kidney transplant they received included additives in the UW solution. Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study HREC/2024/QMS/108359.

Data Collection

Donor characteristics recorded by the ANZDATA Registry included age, sex, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and classified according to the World Health Organization), and donor status such as Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) and Donation after Brain Death (DBD). Recipient characteristics included age, sex, body mass index, medical conditions, extended vs. standard criteria, and graft survival. Extended criteria donor kidney status was defined as donor aged ≥60 years or donor aged ≥50 years with at least 2 comorbidities of hypertension, cerebrovascular disease death, or preterminal donor serum creatinine >132 mmol/L. Immunologic characteristics included ABO incompatibility and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) mismatches.

Outcome

The primary outcomes of this study were DGF, rejection and primary non-function. DGF was defined according to the ANZDATA Registry as the requirement for dialysis within 72 hours of transplantation. Rejection was defined by either clinically-suspected or biopsy-proven rejection for which anti-rejection treatment was administered. Primary non-function was defined as return to dialysis or death with functioning graft. Secondary outcomes include time to all-cause graft loss and death-censored graft loss.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as numbers with proportions for categorical variables. Differences between categorical variables were assessed using the chi-squared test, while differences between continuous parametric variables were evaluated using the Student's t-test. For continuous non-parametric variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was employed. Time-to-event outcomes, including allograft failure, death-censored allograft failure, death, and acute rejection, were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank testing. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed for time-to-event outcomes, and multivariable logistic regression was used to examine factors associated with the use of additives. All statistical analyses and figure generation were performed in R (2025 V 4.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient Characteristics

This study included retrospective analysis of 6,732 kidney recipients, of whom 1532 (30%) received kidneys from a donation state in Australia without the use of additives in UW solution as the local published protocol and 5198 (70%) received kidneys that were procured in states that uses insulin and dexamethasone additives. No statistically significant differences in donor or recipient characteristics between the two preservation groups were found (Table 1) apart from the increased proportion of DCDD (P<0.01) and reduced proportion of extended criteria (P<0.01) donor in the states that used the additives.

|

Characteristic |

Additives N = 5,050 |

No additives N = 1,608 |

p-value |

|

Donor Sex |

0.6 |

||

|

Female |

2,138 (42%) |

692 (43%) |

|

|

Male |

2,912 (58%) |

916 (57%) |

|

|

Donor Height |

172 (165 - 180) |

171 (165, 179) |

0.4 |

|

Unknown |

4 |

0 |

|

|

Donor Weight |

80 (68, 92) |

80 (67, 91) |

0.4 |

|

Donor Age |

49 (36, 59) |

50 (36, 61) |

0.2 |

|

Unknown |

39 |

16 |

|

|

Donor Status |

<0.001 |

||

|

DCDD |

1,593 (32%) |

430 (27%) |

|

|

DBD |

3,457 (68%) |

1,178 (73%) |

|

|

Donor Status |

<0.001 |

||

|

ECD |

1,494 (30%) |

548 (34%) |

|

|

SCD |

3,556 (70%) |

1,060 (66%) |

|

|

Recipient gender |

0.7 |

||

|

Male |

3,182 (63%) |

1,022 (64%) |

|

|

Female |

1,868 (37%) |

586 (36%) |

|

|

Recipient age at transplant |

55 (44, 63) |

54 (43, 62) |

0.3 |

|

Height at time of transplant |

170 (163, 178) |

170 (162, 177) |

0.5 |

|

Unknown |

109 |

34 |

|

|

Weight at time of transplant |

79 (67, 91) |

78 (67, 92) |

>0.9 |

|

Unknown |

223 |

108 |

|

|

1 n (%); Median (Q1, Q3) |

|||

|

2 Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Wilcoxon rank sum test |

|||

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of deceased donors and kidney recipients.

Delayed Graft Function

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the odds of DGF did not differ significantly between groups (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.94-1.27). Factors independently associated with delayed graft function included the total ischemic time, more recent transplantation (2018-2023), HLA DR mismatch, female sex, obesity, the number of years on dialysis, donor age, tubulointerstitial disease, type of donation, and extended donor criteria (Table 2).

|

Multivariable logistic regression: DGF |

|||

|

Characteristic |

OR1 |

95% CI1 |

p-value |

|

Additive Status |

|||

|

Additives |

- |

- |

|

|

No additives |

1.09 |

0.94, 1.27 |

0.3 |

|

Total Ischaemia (to nearest hour) |

1.04 |

1.03, 1.06 |

<0.001 |

|

Era |

|||

|

Early |

- |

- |

|

|

Late |

1.19 |

1.03, 1.37 |

0.017 |

|

HLA a mismatch |

0.93 |

0.84, 1.04 |

0.2 |

|

HLA b mismatch |

1.11 |

0.98, 1.25 |

0.089 |

|

HLA dr mismatch |

1.17 |

1.04, 1.31 |

0.007 |

|

HLA dq mismatch |

1.04 |

0.93, 1.17 |

0.5 |

|

Age at transplant |

1 |

0.99, 1.00 |

0.4 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

|

Female |

0.7 |

0.61, 0.81 |

<0.001 |

|

BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

1.28 |

1.08, 1.52 |

0.004 |

|

Obese |

1.86 |

1.56, 2.21 |

<0.001 |

|

Years on Dialysis |

1.04 |

1.03, 1.06 |

<0.001 |

|

Primary Kidney Disease |

|||

|

Diabetic kidney disease |

- |

- |

|

|

Tubulointerstitial disease |

0.67 |

0.49, 0.94 |

0.019 |

|

Familial / hereditary kidney diseases |

0.76 |

0.56, 1.05 |

0.1 |

|

Glomerular disease |

0.78 |

0.59, 1.03 |

0.079 |

|

Other systemic diseases affecting the kidney |

0.88 |

0.49, 1.57 |

0.7 |

|

Miscellaneous kidney disorders |

0.85 |

0.59, 1.20 |

0.4 |

|

Hypertension / Renal vascular disease |

0.85 |

0.61, 1.18 |

0.3 |

|

Diabetes status at transplant |

|||

|

Diabetes |

- |

- |

|

|

No diabetes |

0.85 |

0.67, 1.07 |

0.2 |

|

Smoking status at transplant |

|||

|

Current/former |

- |

- |

|

|

Never |

1.03 |

0.90, 1.19 |

0.7 |

|

Coronary artery disease at transplant |

|||

|

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.13 |

0.95, 1.34 |

0.2 |

|

Donor age |

1.01 |

1.01, 1.02 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor sex |

|||

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

|

Male |

1.11 |

0.97, 1.29 |

0.14 |

|

Donor BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

1.24 |

1.05, 1.47 |

0.01 |

|

Obese |

1.59 |

1.33, 1.89 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor cause of death |

|||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

- |

- |

|

|

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

1.18 |

0.95, 1.48 |

0.14 |

|

Cerebral Hypoxia / Ischaemia |

1.5 |

1.22, 1.84 |

<0.001 |

|

Non-Neurological Condition |

1.54 |

0.97, 2.45 |

0.067 |

|

Cerebral Infarct |

1.16 |

0.83, 1.62 |

0.4 |

|

Other Neurological Condition |

1.04 |

0.54, 1.89 |

>0.9 |

|

Donor DCDD vs. DBD status |

|||

|

DCDD |

- |

- |

|

|

DBD |

0.24 |

0.21, 0.28 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor ECD vs SCD status |

|||

|

ECD |

- |

- |

|

|

SCD |

0.8 |

0.65, 0.98 |

0.031 |

|

1 OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval |

|||

Table 2: Multivariable logistic regression of delayed graft function (DGF).

Primary Non-Function

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the odds of primary non-function did not differ significantly between both groups, with an OR of 1.15, 95% CI 0.85-1.55. Again, the factors which were independently associated with primary non-function were dialysis vintage year, donor age and the type of donation being DBD donors (Table 3).

|

Multivariable logistic regression: Primary Non-Function |

|||

|

Characteristic |

OR1 |

95% CI1 |

p-value |

|

Additive Status |

|||

|

Additives |

- |

- |

|

|

No additives |

1.15 |

0.85, 1.55 |

0.4 |

|

Total Ischaemia (to nearest hour) |

1.02 |

0.99, 1.05 |

0.11 |

|

Era |

|||

|

Early |

- |

- |

|

|

Late |

0.91 |

0.68, 1.21 |

0.5 |

|

HLA a mismatch |

1.08 |

0.87, 1.34 |

0.5 |

|

HLA b mismatch |

0.94 |

0.74, 1.21 |

0.6 |

|

HLA dr mismatch |

1.24 |

0.98, 1.58 |

0.071 |

|

HLA dq mismatch |

1.02 |

0.81, 1.30 |

0.8 |

|

Age at transplant |

1.01 |

1.00, 1.02 |

0.2 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

|

Female |

1.04 |

0.77, 1.40 |

0.8 |

|

BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

1.32 |

0.93, 1.88 |

0.13 |

|

Obese |

1.33 |

0.92, 1.93 |

0.13 |

|

Years on Dialysis |

1.03 |

1.01, 1.05 |

0.012 |

|

Primary Kidney Disease |

|||

|

Diabetic kidney disease |

- |

- |

|

|

Tubulointerstitial disease |

1.58 |

0.85, 2.87 |

0.14 |

|

Familial / hereditary kidney diseases |

1.34 |

0.73, 2.42 |

0.3 |

|

Glomerular disease |

1.1 |

0.65, 1.85 |

0.7 |

|

Other systemic diseases affecting the kidney |

2.15 |

0.74, 5.40 |

0.13 |

|

Miscellaneous kidney disorders |

1.84 |

0.97, 3.40 |

0.056 |

|

Hypertension / Renal vascular disease |

1.25 |

0.66, 2.28 |

0.5 |

|

Diabetes status at transplant |

|||

|

Diabetes |

- |

- |

|

|

No diabetes |

0.69 |

0.46, 1.06 |

0.081 |

|

Smoking status at transplant |

|||

|

Current/former |

- |

- |

|

|

Never |

0.84 |

0.63, 1.12 |

0.2 |

|

Coronary artery disease at transplant |

|||

|

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.06 |

0.75, 1.48 |

0.7 |

|

Donor age |

1.02 |

1.01, 1.04 |

0.009 |

|

Donor sex |

|||

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

|

Male |

1.09 |

0.82, 1.47 |

0.5 |

|

Donor BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

1.05 |

0.76, 1.47 |

0.8 |

|

Obese |

1 |

0.69, 1.43 |

>0.9 |

|

Donor cause of death |

|||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

- |

- |

|

|

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

1.52 |

0.97, 2.44 |

0.073 |

|

Cerebral Hypoxia / Ischaemia |

1.1 |

0.69, 1.77 |

0.7 |

|

Non-Neurological Condition |

1.71 |

0.72, 3.77 |

0.2 |

|

Cerebral Infarct |

1.09 |

0.54, 2.11 |

0.8 |

|

Other Neurological Condition |

0.48 |

0.03, 2.35 |

0.5 |

|

Donor DCDD vs. DBD status |

|||

|

DCDD |

- |

- |

|

|

DBD |

0.58 |

0.43, 0.79 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor ECD vs SCD status |

|||

|

ECD |

- |

- |

|

|

SCD |

0.65 |

0.43, 1.00 |

0.05 |

|

1 OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval |

|||

Table 3: Multivariable logistic regression of primary non-function.

Rejection

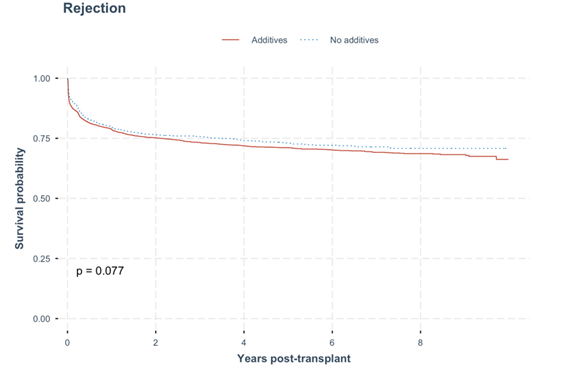

In the multivariable cox regressive analysis, the hazard ratio did not defer significantly between both groups (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84-1.15). Factors independently associated with rejection included HLA B mismatch, HLA DR mismatch, HLA DQ mismatch, age at transplant, BMI - overweight and obese, dialysis vintage year, donor age, donor cause of death being intracranial haemorrhage and type of donation being DBD donors. (Table 4) (Graph 1).

|

Multivariable Cox regression: Time to First Rejection |

|||

|

Characteristic |

HR1 |

95% CI1 |

p-value |

|

Additive Status |

|||

|

Additives |

- |

- |

|

|

No additives |

0.98 |

0.84, 1.15 |

0.8 |

|

Total Ischaemia (to nearest hour) |

1 |

0.99, 1.01 |

0.9 |

|

Era |

|||

|

Early |

- |

- |

|

|

Late |

0.82 |

0.72, 0.93 |

0.002 |

|

HLA a mismatch |

0.98 |

0.90, 1.07 |

0.6 |

|

HLA b mismatch |

1.16 |

1.04, 1.29 |

0.006 |

|

HLA dr mismatch |

1.14 |

1.04, 1.26 |

0.007 |

|

HLA dq mismatch |

1.13 |

1.02, 1.25 |

0.014 |

|

Age at transplant |

0.98 |

0.98, 0.99 |

<0.001 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

|

Female |

0.89 |

0.78, 1.00 |

0.056 |

|

BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

1.23 |

1.06, 1.41 |

0.005 |

|

Obese |

1.3 |

1.12, 1.51 |

<0.001 |

|

Years on Dialysis |

1.02 |

1.01, 1.03 |

<0.001 |

|

Primary Kidney Disease |

|||

|

Diabetic kidney disease |

- |

- |

|

|

Tubulointerstitial disease |

1.06 |

0.80, 1.40 |

0.7 |

|

Familial / hereditary kidney diseases |

1.09 |

0.82, 1.43 |

0.6 |

|

Glomerular disease |

1 |

0.78, 1.28 |

>0.9 |

|

Other systemic diseases affecting the kidney |

0.8 |

0.47, 1.38 |

0.4 |

|

Miscellaneous kidney disorders |

0.9 |

0.66, 1.24 |

0.5 |

|

Hypertension / Renal vascular disease |

1.03 |

0.77, 1.38 |

0.8 |

|

Diabetes status at transplant |

|||

|

Diabetes |

- |

- |

|

|

No diabetes |

0.96 |

0.78, 1.18 |

0.7 |

|

Smoking status at transplant |

|||

|

Current/former |

- |

- |

|

|

Never |

0.94 |

0.83, 1.06 |

0.3 |

|

Coronary artery disease at transplant |

|||

|

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.06 |

0.91, 1.23 |

0.5 |

|

Donor age |

1.01 |

1.00, 1.01 |

0.022 |

|

Donor sex |

|||

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

|

Male |

1.03 |

0.91, 1.16 |

0.7 |

|

Donor BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

0.99 |

0.86, 1.13 |

0.9 |

|

Obese |

0.91 |

0.78, 1.06 |

0.2 |

|

Donor cause of death |

|||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

- |

- |

|

|

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

1.22 |

1.01, 1.47 |

0.038 |

|

Cerebral Hypoxia / Ischaemia |

1.05 |

0.87, 1.25 |

0.6 |

|

Non-Neurological Condition |

1.18 |

0.78, 1.78 |

0.4 |

|

Cerebral Infarct |

1.02 |

0.76, 1.37 |

0.9 |

|

Other Neurological Condition |

1.07 |

0.65, 1.77 |

0.8 |

|

Donor DCDD vs. DBD status |

|||

|

DCDD |

- |

- |

|

|

DBD |

0.79 |

0.69, 0.90 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor ECD vs SCD status |

|||

|

ECD |

- |

- |

|

|

SCD |

0.87 |

0.73, 1.03 |

0.11 |

|

1 HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval |

|||

Table 4: Multivariable Cox regression of time to first rejection.

Graph 1: Overall time to graft rejection. No statistical difference in time to graft rejection was observed between the kidney recipients with donated kidneys that were procured and cold stored in either UW solution with additives or no additives (p = 0.077).

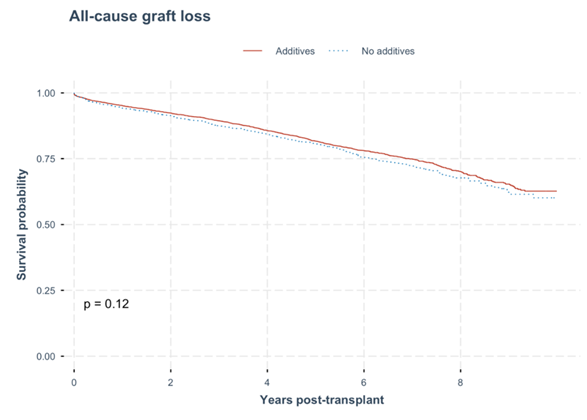

All Cause Graft Loss

In the multivariate cox regression analysis, the hazard ratio of all-cause graft loss did not differ significantly between the groups (HR of 0.94, 95% CI 0.79-1.12). For this group, the factors that were independently associated with all-cause graft loss were dialysis vintage year, familial/ hereditary kidney disease, glomerular disease, absence of diabetes and smoking status, donor age, as well as presence of coronary artery disease at transplant. (Table 5) (Graph 2).

|

Multivariable Cox regression: Time to all-cause graft loss |

|||

|

Characteristic |

HR1 |

95% CI1 |

p-value |

|

Additive Status |

|||

|

Additives |

- |

- |

|

|

No additives |

0.94 |

0.79, 1.12 |

0.5 |

|

Total Ischaemia (to nearest hour) |

1.01 |

0.99, 1.02 |

0.3 |

|

Era |

|||

|

Early |

- |

- |

|

|

Late |

1.06 |

0.89, 1.26 |

0.5 |

|

HLA a mismatch |

1.05 |

0.95, 1.17 |

0.4 |

|

HLA b mismatch |

0.95 |

0.84, 1.07 |

0.4 |

|

HLA dr mismatch |

1.11 |

0.99, 1.25 |

0.079 |

|

HLA dq mismatch |

1.05 |

0.93, 1.18 |

0.4 |

|

Age at transplant |

1 |

1.00, 1.01 |

0.6 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

|

Female |

0.94 |

0.81, 1.10 |

0.4 |

|

BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

0.95 |

0.80, 1.12 |

0.5 |

|

Obese |

0.93 |

0.78, 1.11 |

0.4 |

|

Years on Dialysis |

1.02 |

1.01, 1.04 |

<0.001 |

|

Primary Kidney Disease |

|||

|

Diabetic kidney disease |

- |

- |

|

|

Tubulointerstitial disease |

0.82 |

0.60, 1.13 |

0.2 |

|

Familial / hereditary kidney diseases |

0.72 |

0.52, 0.98 |

0.038 |

|

Glomerular disease |

0.75 |

0.58, 0.98 |

0.037 |

|

Other systemic diseases affecting the kidney |

0.91 |

0.50, 1.66 |

0.8 |

|

Miscellaneous kidney disorders |

1.05 |

0.75, 1.49 |

0.8 |

|

Hypertension / Renal vascular disease |

0.93 |

0.68, 1.26 |

0.6 |

|

Diabetes status at transplant |

|||

|

Diabetes |

- |

- |

|

|

No diabetes |

0.68 |

0.54, 0.85 |

<0.001 |

|

Smoking status at transplant |

|||

|

Current/former |

- |

- |

|

|

Never |

0.77 |

0.67, 0.89 |

<0.001 |

|

Coronary artery disease at transplant |

|||

|

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.27 |

1.08, 1.50 |

0.004 |

|

Donor age |

1.01 |

1.01, 1.02 |

<0.001 |

|

Donor sex |

|||

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

|

Male |

0.94 |

0.81, 1.08 |

0.4 |

|

Donor BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

0.93 |

0.78, 1.09 |

0.4 |

|

Obese |

1.03 |

0.86, 1.23 |

0.8 |

|

Donor cause of death |

|||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

- |

- |

|

|

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

0.96 |

0.77, 1.20 |

0.7 |

|

Cerebral Hypoxia / Ischaemia |

0.96 |

0.77, 1.19 |

0.7 |

|

Non-Neurological Condition |

0.94 |

0.56, 1.59 |

0.8 |

|

Cerebral Infarct |

0.99 |

0.71, 1.37 |

>0.9 |

|

Other Neurological Condition |

0.73 |

0.34, 1.57 |

0.4 |

|

Donor DCDD vs. DBD status |

|||

|

DCDD |

- |

- |

|

|

DBD |

0.91 |

0.77, 1.07 |

0.2 |

|

Donor ECD vs SCD status |

|||

|

ECD |

- |

- |

|

|

SCD |

0.86 |

0.69, 1.06 |

0.15 |

|

1 HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval |

|||

Table 5: Multivariable Cox regression of time to all-cause graft loss.

Graph 2: All-cause graft loss. No statistical difference all-cause graft loss rate was observed between the kidney recipients with donated kidneys that were procured and cold stored in either UW solution with additives or no additives (p = 0.12).

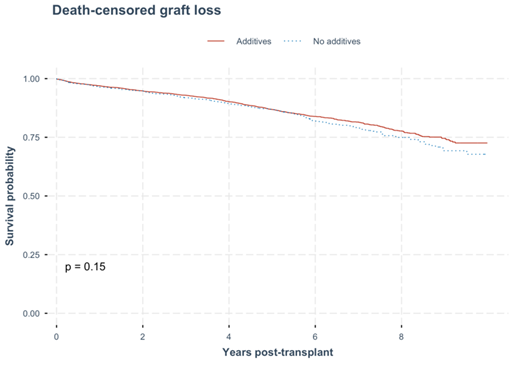

Death-Censored Graft Loss

In the multivariate cox regression analysis, the hazard ratio of death-censored graft loss was not significant between the two groups (HR of 1.08, 95% CI 0.86-1.35. The independent factors that affected death-censored graft loss were age at transplant, female gender, dialysis vintage year, primary kidney disease with glomerular disease, lack of diabetes, non-smoking status, presence of coronary artery disease at transplant and donor’s age. (Table 6) (Graph 3).

|

Multivariable Cox regression: Time to death-censored graft loss |

|||

|

Characteristic |

HR1 |

95% CI1 |

p-value |

|

Additive Status |

|||

|

Additives |

- |

- |

|

|

No additives |

1.08 |

0.86, 1.35 |

0.5 |

|

Total Ischaemia (to nearest hour) |

1.01 |

0.99, 1.03 |

0.4 |

|

Era |

|||

|

Early |

- |

- |

|

|

Late |

1.08 |

0.86, 1.36 |

0.5 |

|

HLA a mismatch |

1.04 |

0.91, 1.20 |

0.6 |

|

HLA b mismatch |

0.93 |

0.79, 1.09 |

0.4 |

|

HLA dr mismatch |

1.11 |

0.95, 1.29 |

0.2 |

|

HLA dq mismatch |

1.03 |

0.88, 1.20 |

0.7 |

|

Age at transplant |

1.04 |

1.03, 1.05 |

<0.001 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

- |

- |

|

|

Female |

0.8 |

0.65, 0.99 |

0.036 |

|

BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

0.9 |

0.72, 1.13 |

0.4 |

|

Obese |

0.87 |

0.68, 1.10 |

0.2 |

|

Years on Dialysis |

1.02 |

1.01, 1.04 |

0.002 |

|

Primary Kidney Disease |

|||

|

Diabetic kidney disease |

- |

- |

|

|

Tubulointerstitial disease |

0.83 |

0.55, 1.24 |

0.4 |

|

Familial / hereditary kidney diseases |

0.75 |

0.50, 1.10 |

0.14 |

|

Glomerular disease |

0.67 |

0.48, 0.93 |

0.018 |

|

Other systemic diseases affecting the kidney |

0.86 |

0.38, 1.91 |

0.7 |

|

Miscellaneous kidney disorders |

1.27 |

0.83, 1.92 |

0.3 |

|

Hypertension / Renal vascular disease |

0.76 |

0.52, 1.13 |

0.2 |

|

Diabetes status at transplant |

|||

|

Diabetes |

- |

- |

|

|

No diabetes |

0.6 |

0.45, 0.79 |

<0.001 |

|

Smoking status at transplant |

|||

|

Current/former |

- |

- |

|

|

Never |

0.76 |

0.63, 0.92 |

0.004 |

|

Coronary artery disease at transplant |

|||

|

No |

- |

- |

|

|

Yes |

1.38 |

1.13, 1.69 |

0.002 |

|

Donor age |

1.01 |

1.00, 1.02 |

0.04 |

|

Donor sex |

|||

|

Female |

- |

- |

|

|

Male |

0.97 |

0.80, 1.17 |

0.8 |

|

Donor BMI |

|||

|

Underweight/normal |

- |

- |

|

|

Overweight |

0.97 |

0.79, 1.21 |

0.8 |

|

Obese |

0.97 |

0.76, 1.23 |

0.8 |

|

Donor cause of death |

|||

|

Traumatic Brain Injury |

- |

- |

|

|

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

0.95 |

0.71, 1.26 |

0.7 |

|

Cerebral Hypoxia / Ischaemia |

0.94 |

0.71, 1.26 |

0.7 |

|

Non-Neurological Condition |

0.6 |

0.27, 1.33 |

0.2 |

|

Cerebral Infarct |

0.94 |

0.61, 1.46 |

0.8 |

|

Other Neurological Condition |

0.95 |

0.38, 2.38 |

>0.9 |

|

Donor DCDD vs. DBD status |

|||

|

DCDD |

- |

- |

|

|

DBD |

1 |

0.81, 1.24 |

>0.9 |

|

Donor ECD vs SCD status |

|||

|

ECD |

- |

- |

|

|

SCD |

0.92 |

0.70, 1.22 |

0.6 |

|

1 HR = Hazard Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval |

|||

Table 6: Multivariable Cox Regression of time to death-censored graft loss.

Graph 3: Death- censored graft loss. No statistical difference in time to death-censored graft loss were observed between the kidney recipients with donated kidneys that were procured and cold stored in either UW solution with additives or no additives (p = 0.15).

Discussion

Preservation Solutions and the History of UW Solution

The history of prolonged hypothermic organ storage and the development of preservation methods that allowed kidney transplants to become semi-elective spans over 50 years [10,11]. In 1967, Belzer at al first described preservation of canine kidneys up to 72 hours with hypothermic oxygenated extracorporeal continuous perfusion and a specialized perfusion solution, then 17-hour cold static preservation and transplantation of human cadaveric kidney in 1968 [10]. Collins solution was subsequently described in 1969 where canine kidneys were cold preserved and reimplanted successfully up to 30 hours after using a novel acellular solution. Since then, a number of milestones have been noted. Euro-Collins (EC) solution was developed in 1980 by Dreikorn et al [12], then followed by the UW solution in 1986 [3]. UW solution is now universally used in Australia for all abdominal solid organs. It became widely used across the world due to the benefits described over Collins and EC fluids for multi-organ preservation including the kidneys, liver and pancreas without the need for organ specific preservation [13-15]. There are now several preservation solutions for use other than Collins/EC/UW such as hyperosmolar (HOC) citrate, Histidine-Tryptophan-Keotglutarate (HTK), Institute Georges Lopez-1 (IGL-1) among others in development or use in perfusion machines. Despite the variations, the preservation solutions all aim to achieve one or more of the following principles in cold organ preservation: 1) reduction of cellular/mitochondrial/tissue swelling; 2) prevention of oxygen-free radicals/ischemic/hypoxic injury; 3) reduction of intracellular acidosis and 4) support for cellular homeostasis [16,17]. Of all the preservation formulae available, only UW solution formulae advocates for additives such as insulin, dexamethasone or penicillin. Nevertheless, retrospective studies, systematic review and meta-analysis have not shown its benefit over others in terms of DGF, primary non-function, graft survival or rejections rates [8,9,18,19]. In addition, similar outcomes were observed with other organs including liver and pancreas [20,21]. As such, the conscientious decision made by several units to omit the use of additives in UW solution became the basis for this study. Based on a comprehensive 10-year, multi-centre, collected registry-based analysis, suggest that the use of insulin and dexamethasone in the UW solution does not significantly impact DGF or graft survival or time to rejection.

Results of the Study

This study examined outcomes in 6,732 kidney transplant recipients, comparing those who received organs preserved in University of Wisconsin solution with additives (insulin and dexamethasone; 70%) to those who received organs preserved without these additives (30%). Key post-transplant outcomes were evaluated, including delayed graft function, rejection, primary non-function, all-cause graft loss, and death-censored graft loss. Across all these outcomes, there were no statistically significant differences between the additive and non-additive groups. For example, delayed graft function had an odds ratio (OR) of 1.09 (95% CI: 0.94–1.27, p=0.3), and graft rejection had a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.84–1.15, p=0.8), indicating no meaningful benefit or harm from the use of additives in the preservation solution. However, several variables were found to be independently associated with poorer transplant outcomes regardless of the solution used. These included transplant factors such as total ischemic time, more recent transplant years (2018–2023), HLA mismatches, donor factors such as age, obesity, type of donation, and recipient factors such as years on dialysis, and certain underlying kidney diseases. Specifically, factors like older donor age and DCDD were recurrently linked to increased risk across multiple outcome measures.

Role of Insulin

Before 1980s, insulin was often included in the literature for pancreas preservation [22]. In 1986, the new lactobionate-raffinose solution (also known today as UW solution) included insulin for the purpose of pancreas preservation over 24 hours. Insulin, a key regulator of glucose metabolism, was thought to help reduce cellular injury during ischemia-reperfusion by stabilizing cell membranes and mitigating the harmful effects of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress [23]. Previous studies have suggested that insulin supplementation can improve tissue energy metabolism, limit endothelial cell injury, and reduce inflammation, all of which are critical factors influencing the success of kidney transplantation. However, the clinical evidence remains mixed, with some studies indicating positive effects while others show no significant improvements [24]. In an Australian study by Biguzas, rat kidney transplant model was used to demonstrate that the isolated omission of insulin in UW solution during preservation resulted in similar serum creatinine and urea, urine volume and potassium concentration in comparison to the control after transplantation (normal UW solution for 48 hours of storage prior to transplantation) [25]. The authors concluded that in kidneys, the insulin may have minimal metabolic effect at hypothermic conditions. The impact of insulin was more pronounced with a rat liver transplant study by Li et al [5] where insulin in UW solution increased ischemia-reperfusion injury and reduced intracellular ATP levels, adversely affecting graft survival. It was associated with an increase in activity of ALT and AST transaminase. Further the addition of insulin to UW significantly reduced the ATP level overall within the tissue, adenine nucleotide pool and energy resources of hepatocytes. The findings may be the result of the lack of glucose in UW solution to allow for insulin to follow with its biology potency although glucose has been excluded in UW solution during its development to reduce the risk of intracellular lactic acidosis. In another study, Yu et al [6] removed individual components of UW for 278 rat liver transplantations. Elimination of insulin in fact improved graft survival after 7 days. Similarly, reporting from the laboratory that described the invention of original UW solution, reported that adenosine, allopurinol, co-trimoxazole, insulin and hydroxyethyl starch could all be omitted without significant changes to the bile flow and enzyme release in isolated perfused rabbit liver model [15].

Role of Dexamethasone

Studies have been utilizing potent steroids in preservation fluid for various organs before 1980’s [2]. It is difficult to ascertain the exact timing when the addition became common, but dexamethasone became a part of the original UW solution formulae in 1986. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties in theory reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury, and subsequent downstream oxidative stress/inflammation/endothelial damage, organ dysfunction or rejection. By mitigating these processes, dexamethasone could protect renal tissue during the critical cold storage phase and improve post-transplant outcomes. Experimental studies have suggested that it could decrease inflammatory mediator release, preserve mitochondrial function, and reduce cell apoptosis, which may be important in marginal or extended criteria donor kidneys. However, overall evidence remains inconclusive. In a rat kidney transplantation study mentioned above by Biguzas et al [25], one of the arms of the transplant model singularly omitted dexamethasone from the UW solution during organ preservation. Of 6 kidneys transplanted, it was noted that no diminution of renal function was noted in comparison to the control (preservation for 48 hours with all the ingredients). In another animal liver transplant model study by Yu et al [6], the most critical soluble components of liver preservation was lactobionate, raffinose and glutathione. The omission of dexamethasone in the study did demonstrate reduction in rat survival with the dose of dexamethasone in UW solution thought to be ideal. Similar to insulin, it has been shown previously that despite the lack of dexamethasone in other types of preservation fluid (e.g. IGL-1, EC, HTK etc), it does not appear to compromise the viability of the organs such as kidney, liver or pancreas during cold storage [8,21,26].

Other Benefits

A secondary consideration is cost-effectiveness. The routine addition of insulin and dexamethasone incurs additional expenses, albeit minor, in the overall cost of transplantation. Given that no significant benefit was observed, removing these additives could contribute to cost savings without potentially compromising graft function. While the estimated savings per litre of UW solution is approximately AUD $11.88 (Australia, 2025), when scaled to national transplantation rates, this could amount to substantial annual reductions in procurement costs. More importantly, many litres of the solutions are often pre-prepared prior to the donation after circulatory determination of death process. When the circulatory determination of death cannot be confirmed within a pre-determined timeframe, the pre-prepared UW solution can no longer by used and discarded. Other benefits to mention include intangible labour time/cost, and risk of contamination of fluid during the preparation. In most of our resource restricted health care service, removing a step from the process could have significant benefits.

Strengths

One of the key strengths of this study is its large sample size within a nation where many similarities are practiced such as the nationalized organ match system, immunosuppression regime, nationalized approach to organ donation through DonateLife, and government funded public health care system to name a few. Furthermore, the data is collected prospectively by dedicated clinical unit data managers which resulted in >95% of data points available for all donors and recipients across the study period.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the exact date at which the protocols changed for the clinical units could not be established from the dataset as the published protocols are annual rather than date specific. Further, as an observational study, it cannot establish causality, and unmeasured confounders may influence results. Variations in surgical techniques in organ procurement and transplantation, evolution of immunosuppression regime, changing patient populations and complexities and ongoing changes to the algorithm in the national organ allocation system over the past decade are only some of the factors that could impact outcomes. With the recent advancement and uptake in the use of machine perfusion with or without oxygenation and normothermic regional perfusion, it was beyond the scope of this article to address the impact of the findings when considering the new technologies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study does not support the routine use of insulin and dexamethasone in the UW solution for kidney transplants based on the lack of significant impact on DGF, graft survival and time to rejection. The addition of insulin and dexamethasone in UW solution appears to be historical with careful theoretical consideration without clinical evidence to support its use. Omission of the ingredients may have the added benefit of reducing direct and indirect costs, and theoretical risk of infection from manually handling of the additives.

References

- Southard JH (1997) Energy metabolism in kidneys stored by simple hypothermia. Transplant Proc 9: 1535-1539.

- Belzer FO (1982) A new perfusate for kidney preservation. Transplantation 33: 322-323.

- Wahlberg JA, Southard JH, Belzer FO (1986) Development of a cold storage solution for pancreas preservation. Cryobiology 23: 477-482.

- Johnson JD (2006) Insulin protects islets from apoptosis via Pdx1 and specific changes in the human islet proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 19575-19580.

- Li XL (2004) Insulin in UW solution exacerbates hepatic ischemia / reperfusion injury by energy depletion through the IRS-2 / SREBP-1c pathway. Liver Transpl 10: 1173-1182.

- Yu WM, Coddington D, Bitter-Suermann H (1990) Rat liver preservation. I. The components of UW solution that are essential to its success. Transplantation 49: 1060-1066.

- Ingulli E (2010) Mechanism of cellular rejection in transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol 25: 61-74.

- O'Callaghan JM (2012) Preservation solutions for static cold storage of kidney allografts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant 12: 896-906.

- Legeai C (2020) Effect of preservation solutions for static cold storage on kidney transplantation outcomes: A National Registry Study. Am J Transplant 20: 3426-3442.

- Belzer FO (1968) Successful seventeen-hour preservation and transplantation of human-cadaver kidney. N Engl J Med 278: 608-610.

- Collins GM, Bravo-Shugarman M, Terasaki PI (1969) Kidney preservation for transportation. Initial perfusion and 30 hours' ice storage. Lancet 2: 1219-1222.

- Dreikorn K, Horsch R, Röhl L (1980) 48- to 96-hour preservation of canine kidneys by initial perfusion and hypothermic storage using the Euro-Collins solution. Eur Urol 6: 221-224.

- Ploeg RJ (1990) Kidney preservation with the UW and Euro-Collins solutions. A preliminary report of a clinical comparison. Transplantation 49: 281-284.

- Alshaibani K (1998) University of Wisconsin versus Eurocollins solution for kidney preservation: analysis of clinical outcome. Transplant Proc 30: 3681-3682.

- Jamieson NV (1988) Preservation of the canine liver for 24-48 hours using simple cold storage with UW solution. Transplantation 46: 517-522.

- Chen J (2019) The Neuroprotective Effects of Necrostatin-1 on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats Are Possibly Mediated by Preventing Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and RIP3-Mediated Necroptosis. Cell Transplant 28: 1358-1372.

- Latchana N (2015) Preservation solutions used during abdominal transplantation: Current status and outcomes. World J Transplant 5: 154-164.

- Stewart ZA (2009) Histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) is associated with reduced graft survival of deceased donor kidney transplants. Am J Transplant 9: 1048-1054.

- Opelz G, Döhler B (2007) Multicenter analysis of kidney preservation. Transplantation 83: 247-253.

- Ferrer-Fàbrega J (2022) Current Trends in Organ Preservation Solutions for Pancreas Transplantation: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Transpl Int 35: 10419.

- Hameed AM (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis of cold in situ perfusion and preservation for pancreas transplantation. HPB (Oxford) 19: 933-943.

- Florack G (1983) Preservation of canine segmental pancreatic autografts: cold storage versus pulsatile machine perfusion. J Surg Res 34: 493-504.

- Cywes R (1992) Effect of intraportal glucose infusion on hepatic glycogen content and degradation, and outcome of liver transplantation. Ann Surg 216: 235-246.

- Li XL (2003) Insulin in University of Wisconsin solution exacerbates the ischemic injury and decreases the graft survival rate in rat liver transplantation. Transplantation 76: 44-49.

- Biguzas M (1990) Evaluation of UW solution in rat kidney preservation. II. The effect of pharmacological additives. Transplantation 49: 1051-1055.

- Szilágyi ÁL (2018) Compared efficacy of preservation solutions on the outcome of liver transplantation: Meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 24: 1812-1824.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.