The Impact of Osteopathic Manual Therapy (OMT) on Physical and Mental Health Using EEG Technology: An Exploratory Case Study

by Kim Calder Stegemann1*, Stephanie Schaub2

1Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, BC, Canada

2Bodyworkx Therapy, Kamloops, BC, Canada

*Corresponding author: Kim Calder Stegemann, Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, BC, Canada.

Received Date: 10 December 2025

Accepted Date: 19 January 2026

Published Date: 22 January 2026

Citation: Stegemann KC, Schaub S (2025) The Impact of Osteopathic Manual Therapy (OMT) on Physical and Mental Health Using EEG Technology: An Exploratory Case Study. Curr Res Cmpl Alt Med 9: 278. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2201.100278

Abstract

There is limited research on the use of Osteopathic Manual Treatment (OMT) on physical and mental health using EEG (electrocochleography) technology, and specifically, using Event Related Potentials (ERP) analysis. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a particular type of mental illness with limited research on OMT as a treatment. This case study investigates the use of OMT with adults who have PTSD symptoms with the addition of EEG and ERP testing. It examines the impact of OMT on mood, pain, autonomic system arousal, surface and cortical brain activity, and brain functioning under task. A case study design was used to track and analyze the impact on an adult male who has a history of trauma as a first responder and military veteran. The participant attended monthly OMT sessions (50-60 minutes in duration) over a six-month period. Qualitative data consisted mainly of clinical notes made by the Osteopathic Manual Practitioner (OMP) and information provided by the client (related to pain, location, intensity, stress levels) during each session. Quantitative data included questionnaires about mood and PTSD symptoms, qEEG (quantitative EEG) and visual ERP data.

OMT was associated with reductions in stress, improved thoracic spine mobility, increased PRM, decreased sympathetic arousal, and faster cognitive processing. While PTSD symptoms remained largely stable, positive trends were seen in mental wellness and depression. EEG findings suggested greater brain efficiency and reduced cortical hyperactivity, particularly in limbic regions. This case study provides a grounding for further research connecting OMT to mental illnesses, such as PTSD and related ANS functioning using EEG technology, with the inclusion of ERP data.

Introduction

Osteopathy holds great hope as a complementary treatment for mental health disorders. In this case study we examine the impact of Osteopathic Manual Treatment (OTM) on the measures of pain, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, including depression and anxiety, overall mental wellness, and autonomic nervous system (ANS) arousal. As OMT strives to influence the ANS through the areas of the origin for the parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS), the areas of interest are the cranium (cerebrum, pons and medulla for the PNS) and the thoracic spine (beginning of the SNS), and are reflected in the treatments in this case study. Our approach is unique in that we are also examining the impact on brain functioning using EEG (electroencephalography) technology, and qEEG (quantitative EEG) and visual ERP (event related potential) reports.

Literature Review

OMT and Mental Health Outcomes

Osteopathic Manual Treatment (OMT) is increasingly recognised for its emerging role in supporting mental well-being. A growing body of literature suggests that OMT may modulate neurophysiological responses related to stress and anxiety, offering a somatic pathway to influence psychological and physiological states.

Abraham et al. [1] conducted a pilot study investigating the effects of OMT on first responders, a population often exposed to high levels of psychological stress. With a specific focus on the suboccipital and thoracic regions and using CV-4 (fourth ventricle compression), the study reported significant reductions in self-reported stress, anxiety, and depression. Others have also investigated the use of OMT as a useful indirect treatment for anxiety and/or depression using a variety of techniques from rhythmic movements of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine segments, to cranial, myofascial, and visceral techniques [2-5].

Some studies had mixed results, however. For example, Fernandez-Perez and colleagues [6] using CV-4 compression, suboccipital muscle release, and deep cervical fascia release found improvements in state anxiety and heart rate, but not in depression, similar to Wiegand and team [7] where first year osteopathic medical students did not respond well to OMT (focusing on rib raising, scapular release, and cervical fascia and occipital compressions) in terms of their depression symptoms. Anxiety and depression are components of PTSD, however, few studies have examined the use of OMT specifically for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [8]. Overall, these studies indicate the need for more research to investigate the connection between OMT and mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

OMT and Autonomic Nervous System Activation

Several studies have also examined OMT’s influence on the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Abenavoli et al. [9] looked specifically at the connection between OMT and saliva flow rate, demonstrating the impact as a reflection of decreased ANS arousal. McParlin et al. [10] discuss the impact of therapeutic touch on pain, noting that with touch, oxytocin is released, decreasing cortisol and downregulating the ANS. Others have examined the connection between OMT and heart rate variability (HRV) and/ or skin conductance, as markers of ANS arousal [5,11,12]. Keller and colleagues [13] noted a decrease in heart rate (HR), increased parasympathetic activity (high frequency 0.15-0.4 Hz), and improvement in HRV (specifically RMSSD - root mean squared strand deviation) after OMT. As Bonnano et al. [14] point out, OMT techniques can impact the ANS, “influencing the sympathovagal balance” (p. 2).

Collectively, these studies support the hypothesis that OMT can positively influence mental health by modulating brain activity and autonomic function. It should be noted, however, that many of these investigations were short in duration. While Edwards and Toutt [4] reported on a 2-week study, others incorporated single, stand-alone sessions [3,5,6].

Neuroimaging and OMT

Advancements in neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques have allowed for more direct assessment of OMT’s impact on brain function. Bonanno et al. [14] conducted a comprehensive review of neuroimaging studies and found that OMT was associated with changes in surface and cortical brain activity, particularly in regions involved in pain, emotion, and interoception.

In terms of surface activity, alpha activity is generally associated with a relaxed, alert state while peak alpha (measured in the occipital region) is related to processing capacity. Some have noted an increase in alpha power following cranial osteopathic techniques [15] such as CV-4 compression [16]. Those researching chronic pain have found a relationship with lowered peak alpha [17], but an increase in peak alpha following the CV-4 technique [18].

Studies utilizing fMRI or resting-state EEG can examine deeper structures such as the cingulate cortex and insula, focusing on interoception, pain, and ANS activity [14]. For example, fMRI studies which found decreased activation in interoceptive networks following OMT, including in patients with chronic low back pain [17] and others have noted changes in connectivity across motor and limbic circuits [19].

To our knowledge, there are no published studies connecting OMT to event related potential (ERP) EEG data. ERP data has been used extensively to analyze brain processing under task [20]. The Oddball task is particularly useful to assess speed, accuracy, brain locking of waves to 13 Hz [21], and how the brain regroups following a response in preparation for the next stimulus (John LeMay, Pathways to Health, July 17 2025, oral communication, johnlemay@me.com). ERP measures such as the P3 latency and amplitude, particularly in visual oddball paradigms, remain unexplored in OMT research.

The current study seeks to build upon this foundation by using EEG technology to examine the effects of OMT on both ANS and psychological parameters for individuals with PTSD, employing a case study design to capture both quantitative and qualitative outcomes, over an extended timeframe (6-month). In addition, with the use of qEEG, surface and cortical changes in brain functioning (beyond just alpha brainwaves) will be investigated, as well as ERP data using the Oddball paradigm.

Methods

Study Design and Recruitment

A case study design was selected for two main reasons: the study is exploratory in nature and also because we wanted to collect indepth qualitative and quantitative data on only a small number of participants. The project was approved by the research ethics board of the local university, to which the first author is affiliated.

The Osteopathic Manual Practitioner (OMP) provided handouts to potential clients in her practice outlining the purpose of our project. The targeted subjects were males and females between 35 and 55 years of age who had reported history of mental health related issues, specifically trauma. To ensure there was no perception of coercion, interested clients were asked to contact the principal investigator (first author of this paper), to indicate their intent to participate. The principal investigator then arranged for a meeting to sign consent forms, and collect initial questionnaires, EEG and ERP data.

Our aim was to include a maximum of 3 participants in the study, but only 2 clients indicated interest. The exclusion criteria were the ability to attend one hour osteopathy sessions at a minimum of once per month for six months paying the standard session fee. In the end, only one was included in this paper; the other person did not follow through with the required sessions.

Data Collection

Data collection included both qualitative and quantitative data. The qualitative data consists largely of the clinical notes taken by the osteopath during the monthly sessions. Quantitative data included three questionnaires and the EEG and ERP pre- and post-test data.

Qualitative Data

The qualitative data were collected at the beginning and end of the monthly sessions. The OMP included information related to current pain level, location of pain occurrence, stress levels, and the interventions provided. Based on the connection between the thoracic spine, cranium, and ANS, the therapist made notes specific to the categories of Central Nervous System/Cranium, Shoulder Joint Pain, and Thoracic Spine. The pain level and the stress level were conducted through the numeric rating scale (NRS) [22] (1 - 10 with 10 being the highest pain) and location of pain with a generic body chart image. Any assigned homework activities were included in the clinical notes. On occasion, the OMP used text messages with the client the day following the sessions to inquire about pain, mobility, and impact of the session. These data were also recorded in the client’s file.

Quantitative Data

Three questionnaires to gauge psychological wellbeing were administered - the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), NPQ (NeuroPsych Questionnaire), and the PCL-5 (PTSD Checklist), all self report measures with strong reliability and validity psychometric properties. The PHQ-9 focuses on depression, consisting of nine questions, the NPQ gauges wellness in 12 different areas (such as anxiety, sleep, attention, fatigues) with 50 questions, while the PCL-5 relates to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms with 20 questions. The client responds using the respective rating scale.

The psychometric data for the three questionnaires is provided below. The PHQ-9 had internal reliability of 0.89 (Cronbach’s alpha) for a primary care audience, and test-re-test reliability of 0.84. The PHQ-9 is related to a well-used measure, the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), with a correlation of 0.90 (area under the curve), and in a ROC analysis, it demonstrated good discriminant ability (0.95) [23]. The NPQ had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) and adequate test-re-test reliability with an average of all categories being 0.74. The NPQ was compared to other specific scales related to each of the subcategories, with an overall “concordance” of 75% [24]. The PCL-5 had strong internal reliability on both total score and sub-scales (Cronbach’s alpha 0.88 and 0.94, respectively). On test-re-test reliability, the subscales ranged from 0.89 - 0.91. The PCL-5 was compared to a single dimension PTSD measure (PPS-I) and the DSM-IV symptom clusters, and demonstrated convergent and discriminate validity with effects sizes between predicted and observed at 0.94 and 0.92, respectively [25].

The EEG data was collected using a 21-sensor cap, and BrainMaster Discovery 24 amplifier. The DC differential amplifier has a sampling rate of 1024 samples/second and a data rate of 256 samples/second. Amplifier bandwidth is 0-100Hz and EEG channel bandwidth is 0-2Hz. The acquisition notch filer was set at 60Hz. Standard 10-20 system Electro Caps were used with tin ground and reference ear clips. To collect ERP data, the Neurofield Q21 amplifier was used with 19 channels plus ground. Input range is +-100mV, using a low pass filter set at ~80Hz and sampling at 256 samples/second. The same Electro Cap (10-12 international system) was used. A tin sensor was also attached to the participant’s left rib area to measure heart rate activity, SDNN (standard deviation of the node-to-node variation), and high and low frequency levels, representing general levels of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity.

Both eyes open and eyes closed at rest recordings were made (5 minutes each). A maximum of 10khoms interference level was acquired before the commencement of recording. To measure brain activity under task, the participant then completed a 600-trial visual Go-No-Go Oddball ERP task. Stimulus/wait duration was 200 msec with a period of 1000msec, and a Go-stimulus frequency of 25%. On the screen the participant was presented with either a green Go sign or a red No sign. They were to click the mouse every time they saw the green Go sign.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Data

The qualitative data was analysed using a thematic approach, using the main categories, as outlined in the clinical notes (pain and stress levels, intervention of Central Nervous System/Cranium, Shoulder Joint Pain, and Thoracic Spine). The osteopath reviewed the notes and identified trends. A trained research assistant reviewed the summary to verify the trends/changes noted.

Quantitative Data

Questionnaire data were reviewed for simple changes in total and scale scores. No statistical analyses of differences were calculated.

The qEEG data was processed using the QEEGPro database/ analysis system. The system does automatic artifacting. The stored EEG per epoch from each channel was converted from the time to the frequency domain via Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT). The results of the FFT were used to calculate the absolute power (µV), the amount of energy within the delta (δ) (1-3 Hz), theta (θ) (4-7 Hz), alpha (α) (8-12 Hz), beta (β) (13-35 Hz), frequency bands, as well as the θ/β ratios of the amplitudes of the 10/20 system electrodes. Surface and cortical brain maps were then generated colour-coding those areas where activity across different brainwave band widths is significantly above or below the average range (+/- 2 standard deviations, SD, from the norm). These were compared for changes from pre- to post-assessment. The cortical maps also included SD measures for structures or Brodmann Area.

The levels of sympathetic and parasympathetic activity were compared pre and post by collecting averages of HR and high and low frequencies (parasympathetic and sympathetic activity, respectively).

Last, the ERP data were analysed in several ways. First, the average (mode) speed of responding to the task, accuracy (wrong or late responses) was noted. The clinician also reviewed the brain’s ability to lock in to complete a task and error-checking using ERSP maps, and how the brain regroups following a response in preparation for the next stimulus using component time response graphs.

Results

Client Profile

Peter (pseudonym) is a 48-year-old former veteran who served in Afghanistan and Kosovo in a special unit, who later has worked as a firefighter and medical first responder. He is self-employed in occupational health and safety, married, and has 3 young adult children living at home. He works out at the gym regularly, lifting weights and doing cardio. Though he acknowledges some PTSD symptoms, he has not sought any psychotherapy. He has mentioned his traumatic childhood with physical abuse and trauma experienced throughout his career, but feels that he has become so numb to it , opting to not “dig it back up”. In his spare time, he works with horses and feels that they help in his journey of healing. During the study, he connected with Veterans Affairs, which initially he resisted, to obtain benefits for his wellness journey.

Qualitative Data

Peter attended eight 1-hour sessions during the 6-month data collection phase. After approximately 10 minutes of doing the selfreport (pain location, stress and pain levels), there was 50 minutes of hands-on treatment.

At the outset, the main areas for pain and somatic dysfunction were identified as:

- T-Spine: the area around T2-T3-T4-T5 with T4 being the most prominent and immobile vertebra

- cranial somatic dysfunctions/ CNS

- both shoulder joints (glenohumeral joints)

A variety of interventions were used. When they appeared to be improving conditions, the technique was repeated the next session until they were no longer indicated.

Cranial: CV4 compression, classical SBS (Sphenobasilar Synchondrosis) hold, tentorium cerebelli and posterior fossa hold.

Upper Thoracic Spine: rib raising, core link, decompaction, myofascial release.

Lower Back and Sacrum: sacral rocking, myofascial release, lumbar roll.

Stress Levels

The OMP noted that there were significant changes from the beginning to the end of each session, reducing by 1 to 2 points (NRS from 1-10). There were changes noted over time, as well Self-reported stress levels were 8-9 at the beginning of the study and reduced by 1 - 2 points at each of the first few subsequent visits. By the third and fourth sessions, his levels were 6 to 7 and remained at that level for the subsequent sessions. He commented that most of his stress was because of the demands of his business.

Central Nervous System/Cranium

Cranial rhythm (Primary Respiratory Mechanism - PRM) varied over time. On the initial assessment it was at 0/min with the cranium perceived to be in a ‘freeze’ state (emotional sympathetic state), a certain type of vibrational tissue tension perceived by the practitioner. His whole body felt extremely tense.

Near the end of the series of sessions, the PRM measured 8/min, and the vibrational state had eased off (norm for PRM being 8-12/ min).

Shoulder Joint Pain

Peter experienced no significant changes in shoulder pain throughout the treatment. Pain occurrence in the beginning of the treatment was 7 out of 7 days (pain mostly at night), with pain level at 8. The pain seemed to be linked to his workout routine, which he acknowledged was perhaps too rigorous, but what he felt that he needed for good mental health.

At the end of the study the pain was at 7, still 7 /7 nights.

Thoracic Spine

T4 often became the focus because of the rigidity of the segments and its connection to the SNS[1]. The T-spine appeared to be related to his shoulder joint pain but ended up not being influenced much by the improvement of the thoracic segment.

Initially the T-spine got worse. Pain levels went from 3-4, then peaked at 8/10 mid-study, but eventually reduced to 1-2 on palpation of the spinal processes. The vertebra mobility improved (reported by OMT and client).

General Observations

Initially during the sessions, the client couldn’t close his eyes in supine position and felt very rigid, unable to relax. He would anticipate touch and felt very uneasy with the physical contact and the act of releasing tension in his body. He equated it to losing control.

After three sessions the client started feeling more relaxed and confident in being treated and receiving OMT. He was able to close his eyes and would start drifting off into sleep. By session five and six, the client would fall asleep multiple times during the session and then verbalized interest and positivity towards the upcoming planned treatments.

At the end of the series of sessions which were part of this study, the client stated that he enjoyed coming and was seeking out further osteopathy treatment.

Quantitative Data

Questionnaires

In general, Peter had improvements in measures of overall depression, wellness, and some post traumatic stress symptoms (Table 1). The PHQ-9 overall score was reduced from 4 to 1. The NPQ had decreased levels of severity in 6 of the categories (attention, impulsivity, memory, mood stability, aggression, and pain). No changes were noted in anxiety, fatigue, or sleep. More inconsistent changes were found with the measure of post traumatic stress symptoms (PCL-5). While negative cognitions and mood, and levels of arousal and reactivity both decreased, there was no change in measure of intrusive thoughts and an increase in persistent avoidance behaviours.

1The paravertebral sympathetic chain is at T1 and goes down to L2-L3. Lungs, heart, head, and neck receive sympathetic innervation from the upper area between T1 and T5. T4 is significant because the heart (rate, blood pressure, and bronchial tone) can be impacted by bodywork.

|

Dec 2023 |

July 2024 |

||

|

PHQ Total Score |

4 |

1 |

|

|

NPQ (categories) |

|||

|

Attention |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Impulsive |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Memory |

4 |

3 |

|

|

Anxiety |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Panic |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Depression |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Mood Stability |

7 |

2 |

|

|

Aggression |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Fatigue |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Sleep |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Suicide |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Pain |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Total Score |

29 |

17 |

|

|

PCL-5 (sub-scales) |

|||

|

Intrusive Thoughts |

7 |

7 |

|

|

Persistent Avoidance |

4 |

6 |

|

|

Negative Alteration in Cognition & Mood |

11 |

10 |

|

|

Alteration in Arousal & Reactivity |

11 |

9 |

|

|

Total Score |

33 |

32 |

|

Table 1: Questionnaires (PHQ, NPQ, and PCL) Pre-Post Scores.

EEG and HRV Data

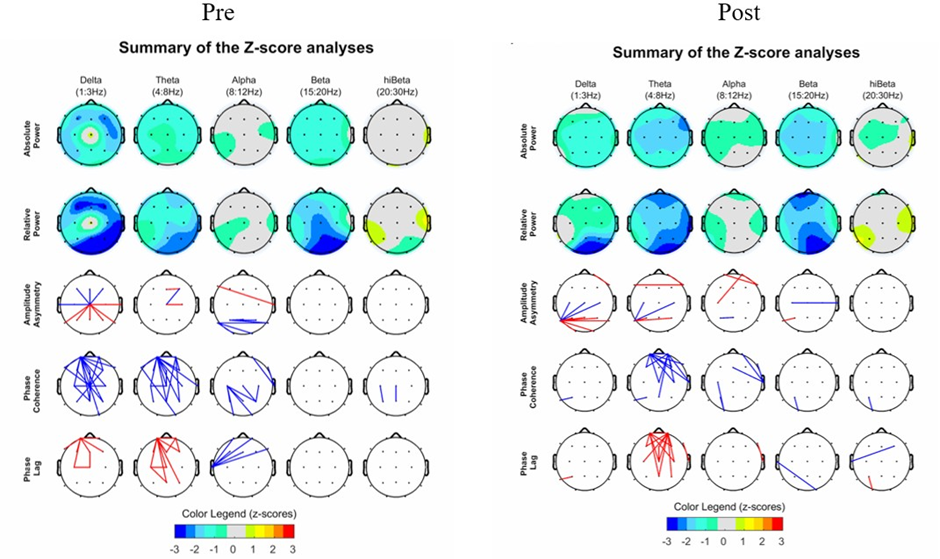

On the surface, there was a slight decrease in activity in the central area across alpha and beta bands (Linked Ears Montage, Eyes Closed condition) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pre- and Post Surface Maps, Linked Montage, Eyes Closed Condition.

The peak alpha showed an increase. In the occipital lobe at locations O1/O2, pre-peak alpha levels were 10.82 and 10.89, and post showed an increase to 11.01 and 11.09. These findings are consistent with those found by de Vries et al. [17] and Martins et al. [18].

The most striking difference in cortical EEG activity was in the lo-beta, beta, hi-beta, and gamma bands (Table 2). Note the decrease in fast wave activity, particularly in the limbic area, and specifically in the anterior cingulate, which could be reflective of a decrease in sympathetic arousal. Note that these changes were only evident in the EO condition. With EC, there was a notable reduction in slowwave activity (from +3.0 to -2.5 SD), and an increase in hi-beta activity from -2.9 to +2.1 SD).

|

Eyes Open |

Dec 2023 |

July 2024 |

|

|

Band |

|||

|

Delta (1-3 Hz) |

-2.9 LL, BA27 |

-2.9 LL, BA43 |

|

|

Theta (3-7 Hz) |

-2.2 LL, BA25 |

-2.8 LL, BA24 |

|

|

Alpha (8-12 Hz) |

-2.1 Sublobar, BA12 |

-2.8 TL(r)1 , BA24 |

|

|

Lo-Beta (13-15 Hz) |

2.9 LL, BA 28 |

-2.6 TL(r), BA21 |

|

|

Beta (16-20 Hz) |

4.0 LL, BA28 |

-2.8 TL(r), BA 41 |

|

|

Hi-Beta (21- 30Hz) |

7.1 LL, BA27 |

5.0 LL, BA24 |

|

|

Gamma (35-45 Hz) |

5.4 LL, BA28 |

2.9 LL, BA25 |

|

|

Eyes Closed |

|||

|

Delta (1-3 Hz) |

3.0 FL, BA6 |

-2.5 Sublobar, BA13 |

|

|

Theta (3-7 Hz) |

-1.8 LL, BA25 |

-2.3 Sublobar, BA 24 |

6

|

Alpha (8-12 Hz) |

-2.1 TL (l), BA20 |

-2.3 n PL (l), BA 43 |

|

|

Lo-Beta (13-15 Hz) |

-2.4 LL, BA 36 |

-2.8 Insula (l), BA 13 |

|

|

Beta (16-20 Hz) |

-2.4 LL, BA 36 |

-2.8 Insula (l), BA 13 |

|

|

Hi-Beta (21- 30Hz) |

-2.9 PL, BA 7 |

2.1 PL, BA 7 |

|

|

Gamma (35-45 Hz) |

2.5 PL, BA7 |

2.0 PL, BA7 |

|

|

Note: 1. r or l indicates right or left hemisphere, 2. FL - Frontal Lobe, LL - Limbic Lobe, PL - Parietal Lobe, TL - Temporal Lobe. |

|||

Table 2: Pre and Post Cortical Activity Levels by Band (SD) Brain Lobe and Brodmann Area.

There was an improvement in the heart rate variability measures (Table 3). In terms of levels of arousal, his HR reduced from 90.7 to 74.08 bpm, SDNN improved from 29.85ms (below average heart rate variability) to 61.69ms, slightly above average heart rate variability [26]. Levels of sympathetic activity reduced from normalized power of 53.39 to 38.31, however there was no increase in

parasympathetic activity, both pre and post remaining at 0.

|

July 2024 |

Dec. 2024 |

|

|

HR (bpm) |

90.7 |

74.08 |

|

SDNN (msec) |

29.85 |

61.69 |

|

Sympathetic Normalized Power |

53.39 |

38.31 |

|

Parasympathetic Normalized Power |

0 |

0 |

Table 3: Figure 2. Pre and Post HR and CNS Measures.

ERP Data

The ERP data indicated a decrease in processing speed (Table 4). Peter’s most common processing speed at the beginning of the project was 555msec and at the end it was 531msec, a decrease of 24 msec. Accuracy did not change, with the number of Missed/ late or Wrong responses, both remaining at 0 and 1, respectively at pre- and post-testing.

|

July 2024 |

Dec. 2024 |

|

|

Processing Speed (Mode) |

555msc |

531msc |

|

Missed/Late Responses |

0 |

0 |

|

Wrong Responses |

1 |

1 |

Table 4: Pre and Post ERP Processing Speed and Accuracy.

The component time response graph indicates a settling of pre-stimulus brain chatter (before the black line), and a more coordinated P3 response (after stimulus) after the course of

the OMT treatments (Figure 2). ERSP maps show a decline,

not an improvement, in resource locking. Initially, there were several sensor locations that exceeded the 13Hz mark (red

spots), indicating perhaps overprocessing or over vigilance.

There was more fast wave interference in post-testing, and fewer clear locking. Similarly, error checking (typically represented by the blue spots) was not improved.

Discussion

OMT was associated with reductions in stress, improved thoracic spine mobility, increased PRM, decreased sympathetic arousal, and faster cognitive processing. While PTSD symptoms remained largely stable, positive trends were seen in mental wellness and depression. EEG findings suggested greater brain efficiency and reduced cortical hyperactivity, particularly in limbic regions. The pain in his shoulders did not subside and was attributed to his rigorous workout routine. Peter’s ability to trust and relax has significantly improved throughout the study.

Since most of OMT is measurable through ROM, NRS and subjective feedback, and the feel/palpation of the practitioner, the opportunity to include physiological and psychological measures, along with EEG data, are welcomed additions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Our case study provides a grounding for further research connecting OMT to mental illnesses, such as PTSD and related ANS functioning using EEG technology, with the inclusion of ERP data.

Future studies could be larger, to include RCT with control and treatment groups. In addition, the inclusion of patient interoception would be an interesting component to include, examining the connection between brain functioning, ANS arousal, and body awareness/self-regulation, possibly using the framework developed by Bohlen et al. [27] related to faulty interoception. In terms of improvements for OMT, we suggest using specific techniques for the purposes of replication. Further, since the families of individuals struggling with PTSD are likely impacted, we propose that the perception of family members about changes in mood, pain, and overall wellness would provide important information. Last, the inclusion of network maps from EEG data could add to the body of knowledge of the complex interplay between brain and body, and more studies utilizing ERP data are needed.

Author Contributions: Kim Calder Stegemann - conception, data acquisition/analysis/interpretation, drafted, revised/formatted manuscript.

Stephanie Schaub - conception, data acquisition/analysis/ interpretation, drafted.

Financial Disclosures: No external funding was accessed to conduct this study.

There is no conflict of interest for the first author, who had no financial gains by participating in this study.

The second author was paid for OMT services by the participant in this study. She had no other financial gain by participating in this study.

References

- Abraham C, Sloan SNB, Coker C, Freed B, McAuliffe M, et al. (2021) Osteopathic manipulative treatment as an intervention to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression in first responders: A pilot study. Mo Med 118:435-441.

- Dixon L, Fotinos K, Sherifi E, Lokuge S, Fine A, et al. (2020) Effect of osteopathic manipulation therapy on generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Osteopath Assoc 120:133-143.

- Dugailly PM, Fassin S, Maroye L, Evers L, Klein P, et al. (2014) Effect of a general osteopathic treatment on body satisfaction, global selfperception, and anxiety: a randomized trial in asymptomatic female students. Int J Osteopath Med 17:94-101.

- Edwards DJ, Toutt C (2018) An evaluation of osteopathic treatment on psychological outcomes with patients suffering from chronic pain: a prospective observational cohort study collected through a health and well-being academy. Health Psychol Open 5: 2055102918774684.

- Hope-Bell J, Draper-Rodi J, Edwards DJ (2023) Applying an osteopathic intervention to improve mild to moderate mental health symptoms: a mixed-methods feasibility study protocol. BMJ Open 13:e071680.

- Fernández-Pérez AM, Peralta-Ramírez MI, Pilat A, Moreno-Lorenzo C, Villaverde-Gutiérrez C, et al. (2013) Can myofascial techniques modify immunological parameters? J Altern Complement Med 19:2428.

- Wiegand S, Bianchi W, Quinn TA, Best M, Fotopoulos T (2015) Osteopathic manipulative treatment for self-reported fatigue, stress, and depression in first-year osteopathic medical students. J Am Osteopath Assoc 115:84-93.

- Bowes MR, Speicher MR, Tran LA, Santiago PN (2023) Osteopathic manipulation medicine and its role in psychiatry. Cureus 15:e47045.

- Abenavoli A, Badi F, Barbieri M, Seppia S, Tresoldi M, et al. (2020) Cranial osteopathic treatment and stress-related effects on autonomic nervous system measured by salivary markers: a pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 24:215-221.

- McParlin Z, Cerritelli F, Rossettini G, Friston KJ, Esteves JE (2022) Therapeutic alliance as active inference: The role of therapeutic touch and biobehavioural synchrony in musculoskeletal care. Front Behav Neurosci 16:897247.

- Arienti C, Farinola F, Ratti S, Daccò S, Fasulo L (2020) Variations of HRV and skin conductance reveal the influence of CV4 and Rib Raising techniques on autonomic balance: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther 24:395-401.

- Cerritelli F, Cardone D, Pirino A, Merla A, Scoppa F (2020) Does osteopathic manipulative treatment induce autonomic changes in healthy participants? A thermal imaging study. Front Neurosci 14:887.

- Keller M, Perlitz V, Pelz H, Borik S, Repik I, et al. (2024) On the specificity of manual triggers of autonomic nervous system responses using osteopathic cranial manipulative medicine. bioRxiv.

- Bonanno M, Papa GA, Ruffoni P, Catalioto E, De Luca R, et al. (2024) The effects of osteopathic manipulative treatment on brain activity: A scoping review of MRI and EEG studies. Healthcare 12:1353.

- Cella M, Acella E, Aquino A, Pisa V (2022) Cranial osteopathic techniques and electroencephalogram (EEG) alpha power: a controlled crossover trial. J Osteopath Med 122:401-409.

- Miana L, do Vale Bastos VH, Machado S, Arias-Carrión O, Nardi AE, et al. (2013) Changes in alpha band activity associated with application of the compression of fourth ventricular (CV-4) osteopathic procedure: A qEEG pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 17:291-296.

- de Vries M, Wilder-Smith OH, Jongsma ML, van den Broeke EN, Arns M, et al. (2013) Altered resting state EEG in chronic pancreatitis patients: toward a marker for chronic pain. J Pain Res 6:815-824.

- Martins WR, Diniz LR, Blasczyk JC, Lagoa KF, Thomaz S, et al. (2015) Immediate changes in electroencephalography activity in individuals with nonspecific chronic low back pain after cranial osteopathic manipulative treatment: study protocol of a randomized, controlled crossover trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 15:223.

- Cerritelli F, Chiacchiaretta P, Gambi F, Saggini R, Perrucci MG, et al. (2021) Osteopathy modulates brain–heart interaction in chronic pain patients: an ASL study. Sci Rep 11:4556.

- Luck SJ (2014) An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kropotov JD (2016) Functional Neuromarkers for Psychiatry: Applications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press.

- Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M (2007) Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 22:1453-1458.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med 16:606-613.

- Gualtieri CT (2007) An Internet-based symptom questionnaire that is reliable, valid, and available to psychiatrists, neurologists, and psychologists. MedGenMed;9:3.

- Wortmann JH, Jordan AH, Weathers FW, Resick PA, Dondanville KA, et al. (2016) Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychol Assess 28:1392-1403.

- van den Berg ME, Rijnbeek PR, Niemeijer MN, Hofman A, van Herpen G, et al. (2018) Normal values of corrected heart-rate variability in 10-second electrocardiograms for all ages. Front Physiol 9:424.

- Bohlen L, Shaw R, Cerritelli F, Esteves JE (2021) Osteopathy and mental health: An embodied, predictive, and interoceptive framework. Front Psychol 12:767005.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.