Surgical Treatment of a Rare Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor with Hepatic Resection: A Case Report

by Anna Sarkisova1, Joyce Eum1, Michael Bush2, Bhavna Khandpur2, Krist Aploks1, Minha Kim1, Ronald Truong1, Marissa Crofut1, Xiang (Eric) Dong1*

1Division of Surgical Oncology, Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, Danbury Hospital, CT, USA

2Department of Pathology, Norwalk Hospital, CT, USA

*Corresponding author: Xiang Da (Eric) Dong, Nuvance Health; Division of Surgical Oncology, Praxair Cancer Center, 95 Locust Avenue, Danbury CT, 06810, USA

Received Date: 26 July 2024

Accepted Date: 29 July 2024

Published Date: 31 July 2024

Citation: Sarkisova A, Eum J, Bush M, Khandpur B, Aploks K, et al. (2024) Surgical Treatment of a Rare Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor with Hepatic Resection: A Case Report. J Surg 9: 11098 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.11101

Abstract

Introduction: Although liver is the most common site of metastasis from gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NETS), Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PHNET) has been described. PHNET is a diagnosis of exclusion with imaging studies, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry. Treatment approaches range from observation to medical and surgical interventions depending on the location, size, grade, stage, and hormonal activity of the tumor. Surgical resection of the tumor is often considered effective if the tumor is localized and can be safely removed without affecting liver function.

Method(s): We present a case of an 81-year-old woman admitted for an unprovoked pulmonary embolism with an incidental finding of enlarging right hepatic multiloculated lesion. Complete surgical resection of right hepatic segments 6-8 and cholecystectomy were performed via an open approach assisted with intraoperative ultrasound. There was no evidence of primary disease in the peritoneal cavity or metastatic disease.

Results: Definitive diagnosis of PHNET was confirmed both immunohistochemically and by absence of extrahepatic primary sites based on imaging studies.

Conclusion(s): There are no officially accepted treatment guidelines for PHNET, however we propose that complete surgical resection of PHNET carries a favorable outcome due to potential of a complete cure.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine Tumors (NET) originate from neuroendocrine cells, found in various organs, and have characteristics of both nerve cells and hormone-producing cells. More than 50% of these tumors originate from gastrointestinal tract including the stomach, pancreas, small intestine, appendix, colon, and rectum [1]. Smaller percentage of tumors originate from the tracheobronchopulmonary system [2,3]. Liver is the most common location for metastatic NET [1]. However, Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (PHNETs) are rare, accounting for only 0.3% of all neuroendocrine tumors [1]. These tumors are slow growing and are proposed to originate from intrahepatic bile duct epithelium [4,5]. The incidence and prevalence of primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors is highly variable. Thus far, many online databases are mostly filled with few case report findings. To date, there have been less than 150 - 200 cases reported in literature [4,6].

Symptoms from PHNETs are nonspecific and may not be present especially early on in clinical presentation, however in later stages, mass effect of the tumor contributes to symptomology. Clinical presentation can vary depending on factors such as the size, location, and hormonal activity of the tumor. Common symptoms associated with PHNET include abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea and vomiting, jaundice, fatigue. Interestingly hormonal effects are very uncommon in PHNET [4]. Diagnosis for PHNET is difficult and requires a multimodal approach of imaging studies such as CT scans or MRI, immunohistopathologic evaluation and biopsies. Since the most common site of metastasis of gastrointestinal NETS are to the liver and primary NET in the liver is very rare, diagnosis of extrahepatic lesions must be excluded. The treatment approach for PHNET ranges from observation to medical and surgical interventions depending on the location, size, grade, stage and hormonal activity of the tumor. Surgical resection of the tumor is often considered if the tumor is localized and can be safely removed without affecting liver function. This is more feasible for smaller tumors and those that have not spread to other organs.

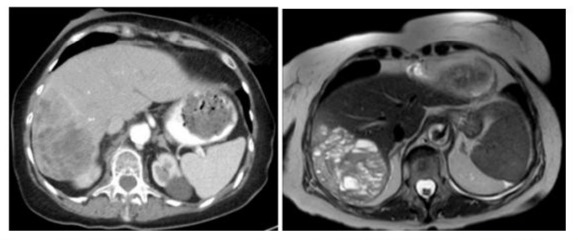

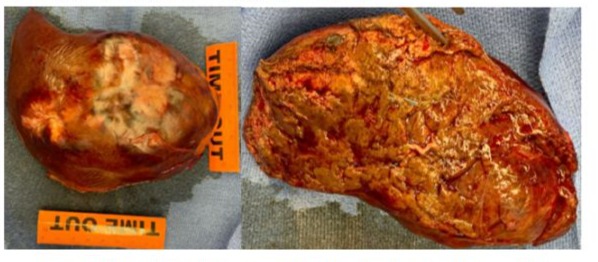

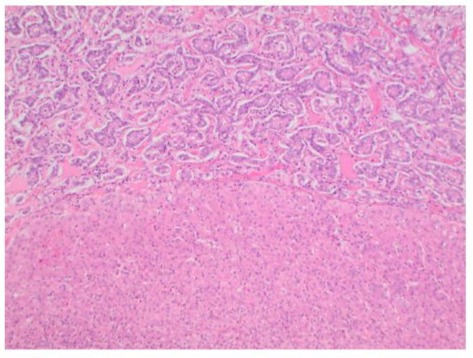

Case

A 81-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for an unprovoked Pulmonary Embolism (PE) who was incidentally found to have a large right-sided liver mass. During work up of PE, CT imaging studies revealed an enlarging cystic lesion in the right lobe of the liver. The patient’s physical exam was unremarkable, the abdomen was non-tender, non-distended throughout and without appreciable hepatosplenomegaly. The patient denied a history of jaundice, vomiting, flushing, or diarrhea. Laboratory tests had normal liver function tests. Patient’s past medical history was significant for having incidental finding of a cystic liver lesion after undergoing a CT abdomen for diverticulitis work up five years prior to current admission. At that time, the patient had a 2.4 cm complex cyst in segment 6 of the liver in addition to a hemangioma in segment 4. Tumor markers of CEA, CA 19-9 and AFP levels were normal. She was otherwise asymptomatic from the cyst and LFTs were also normal. In this admission, repeat CT imaging revealed a multiloculated cystic mass in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe measuring approximately 11.4 x 7.8 x 8.6 cm which had a significant interval increase in size. (Figure 1). Given these findings, the patient underwent a complete surgical resection of right hepatic segments 6, 7, 8, with en-bloc cholecystectomy. There was no evidence of subclinical primry lesions, peritoneal carcinomatosis, or metastatic disease. The mass is illustrated in Figure 3. Gross specimen with 1 cm margins was analyzed by two separate pathology groups. Post operatively patient’s recovery was uneventful. Definitive post-surgical diagnosis revealed a well-differentiated NET, G2 with signet ring features confined to posterior liver with negative margins. (Figure 2) The tumor had a low proliferation index with mitotic rate of 2 mitoses per 2 mm2 and Ki-67 labeling index of 3%. Adjacent liver tissue was without significant primary hepatic abnormalities. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor was strongly positive for synaptophysin, Cam 5.2 and CD56. There was weak to moderate positivity for chromogranin and a moderate positivity for CK AE 1/3. Microscopic morphology is illustrated in Figure 3.The tumor was negative for S100, HepPar 1, CK 5/6, CK7 and CK20 ruling out metastatic tumors or other types of primary liver malignancies. Mucicarmine stain and PAS stain were also negative. Tumor specimen was reviewed by a second pathology group for expert review. Their findings were consistent with the original pathology report and suggested a diagnosis of well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of primary hepatic origin. One month follow up PET-DOTATE scan was negative for extrahepatic NET lesions, with no evidence of recurrence or metastatic disease. The final diagnosis of Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (PHNET) was established.

Figure 1: A. CT scan showing a large heterogeneously enhancing mass of the right hepatic lobe B. MRI of multiloculated cystic mass in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe measuring approximately 11.4 x 7.8 x 8.6 cm.

Figure 2: Gross specimen of resected tumor and right hepatic segment 6,7,8.

Figure 3: Microscopic appearance of the tumoral lesion (T) in the resected liver specimen compared to normal liver tissue bed (N). The architectural pattern is trabecular and glandular with nested cells. H&E x 100.

Discussion

PHNET is a very rare tumor, and it requires strict exclusion from other more common hepatic malignancies such as carcinoid metastasis, cholangiocarcinoma, hepatic adenoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma [7,8]. Diagnosis is primarily made with immunohistochemistry and radiological exclusion of metastatic disease from gastrointestinal or systemic origin. Imaging guided diagnosis such as octreotide scintigraphy (OctreotrideScan) and Ga-68 Dotatate PET-CT scan have been used in the preoperative and postoperative settings to identify primary location of the tumor [9]. To date, there are no specific imaging guidelines to diagnose PHNET which makes it very difficult to make an accurate diagnosis without analyzing the surgical specimen [9]. The high lesion to background resolution of Ga-68 Dotatate PET-CT scan make it a very sensitive tool to rule in the diagnosis of PHNET as it identifies any extrahepatic NETS or metastasis [9]. Utilization of this scan preoperatively is a way to identify lesions that can be surgically resected. Postoperatively, the test can be used to identify extrahepatic lesions and monitor recurrence [10]. Additionally, laboratory markers such as AFP, CEA, CA19-9 are not very helpful in diagnosis of PNHET as they are usually within normal limits. (lia-xing) Blood levels of chromogranin A or serotonin do not aid in differentiating PHNET from other forms neuroendocrine neoplasms. Pathological features of hepatic NETs generally appear macroscopically as brown to yellow-grey colored, well demarcated lesion with irregular hemorrhagic areas containing cystic components. (source) In our presented case, the tumor had cystic component on CT, and irregular bordered necrotic yellow mass on gross specimen. (Figure 2) Microscopic appearance of the tumor exhibits an insular, nested, trabecular or a mixed pattern of cell growth. (Figure 3) In literature, they are described to be positive for chromogranin A, CD 56 and synaptophysin A. (source everyone) Our findings are supported by this evidence. Cellular assessment of the tumor is an adequate tool to predict malignant potential of these tumors [11]. The 2019 WHO classification of NET consists of three grades (G1, G2 and G3) which are related to the mitotic index and ki-67 index: NET G1 presents, respectively <2 and < 3 %, NET G2 is 2-20 and 3-20 %, and NET G3 > 20 and >20 %, respectively [11,12]. In our presented case, the tumor had low - medium malignancy potential with Ki-67 of 3% placing it as a G2.

PHNETs are mostly diagnosed past the 6th decade of life and a lot of times the disease course is indolent and asymptomatic. Symptomatic cases have mainly nonspecific presentation such as abdominal distention, fatigue, and nausea, and without endocrinological effects, thus diagnosis can be significantly delayed and made when the tumor is too large for resection [13]. Treatment therapies proposed for PHNET are highly variable. Transarterial chemo-embolization (TACE) or ablation may be used to shrink or control the tumor growth [2] For tumors that produce hormones, somatostatin analogs can be used to control symptoms and slow down tumor growth [2] Chemotherapy is generally less effective and maybe considered if there is unresectable disease [2]. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy (PRRT) delivers radioactive particles to the tumor cells to target specific receptors on the tumor cells. (spaho) All of these treatments have been used to treat gastrointestinal or pancreatic NETS that metastasize to the liver but their efficacy on PHNET is poorly studied. (chen) As more cases have been reported in literature, efforts have been made by the scientific community to research and define the best care and treatment for these patients. Several studies propose that surgical resection of the tumor is the best curative treatment to date [14]. A recent study of SEER data found that patients with PHNET who underwent surgery predicted better OS and DSS [15]. According to Jung et al., surgical treatment is recommended because of the favorable postresection outcomes as they report a 5-year and 10-year survival rates of 70.0% and 70.0%, respectively [16]. For non resectable tumors, in which postoperative residual hepatic tissue is not insufficient to maintain normal physiological function, an associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) surgical approach has been shown to be successful in several case reports [13,14,17]. In rare cases, a liver transplant may be an option for patients with primary hepatic NETs that cannot be completely removed by surgery. Even in a setting of poor liver function, surgical approach to hepatic tumor resection is being innovated to improve outcomes. The case presented in this paper further supports the notion that surgical resection of PHNET is the best treatment option that we have right now.

The treatment decision is highly individualized and should be based on a thorough assessment of the patient's condition and preferences. Since primary hepatic NETs are exceptionally rare and difficult to diagnose, it's important to seek care at a medical center with expertise in treating neuroendocrine tumors. Patients should have open and thorough discussions with their healthcare team to fully understand their diagnosis, treatment options, potential benefits, risks, and expected outcomes. It is important to consider creating a pathway for preoperative diagnosis and post operative management of these tumors as patients remain 70% disease free at 5 years post surgery and reccurence rate is 18% [15,16,18-27]. The patient in our case remained disease free after surgery at 3 month post operative evaluation and we will continue to follow up with Ga-68 Dotatate PET-CT scan to monitor for any recurrence.

References

- Alghamdi HM (2023) A rare primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumour with laparoscopic resection: a case report. J Med Case Rep 17: 296-z.

- Chen N, Slater K (2019) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumours-Case series of a rare malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep 55: 145-148.

- Tuan Linh L, Minh Duc N, Tu Minh H, et al. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2021: 20-0220.

- Yu W, Li R, Sun B, Du J, Tuo H (2021) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumour with multiple liver metastases: A case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 89: 106590.

- Londhe M, Garg S, Gurwale S, Gore C (2023) Cystic presentation of primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumour: a case report with a brief review of literature. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 4: 266-272.

- Quartey B (2011) Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: What Do We Know Now?. World J Oncol 2: 209-216.

- Wang L, Liu K, Lin G, Jiang T (2015) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors: comparing CT and MRI features with pathology. Cancer Imaging 15: 13.

- Huang H, Jin P, Yang H (2020) Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Mimicking Ruptured Hepatocellular Carcinoma with AFP Elevation: A Case Report and Literature Review. Onco Targets Ther 13: 975-979.

- Gorla AKR, Basher RK, Kaman L, Bal A, Bhattacharya A, et al. (2017) 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. Clin Nucl Med 42: 118-120.

- Jiao X, Luan W, Peng X, Liu L, Zhang L, et al. (2020) Effects of tumor origins and therapeutic options on the prognosis of hepatic neuroendocrine tumors: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 99: e23655.

- Costa AC, Santa-Cruz F, Guimarães H (2020) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 72: 1-4.

- Qiu M, Chen Y, Bi N, Yang S, He X, et al. (2018) Comparative Clinical Analysis of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Carcinomas with Liver Metastasis and Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Carcinomas. Dis Markers 2018: 9191639.

- Qu C, Qu L, Zhu C, Wang Z, Cao J (2018) Treatment of primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors with associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy (ALPPS): A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 97: e12408.

- Nadalin S, Castro-Santa E, Capobianco I, Singer S, Hinterleitner M, et al. (2022) ALPPS for primary neuroendocrine tumor of the liver (PHNET): Report of challenging clinical and surgical case and review of the literature. International Journal of Surgery; Abstracts of the 4th International Advanced Liver & Pancreas Surgery Symposium (ISLS 2021) 100: 106408.

- Lin J, Li X, Ding X, Chen Z, Wu Y, et al. (2022) Developing a competing risk nomogram that predicts the survival of patients with a primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor. Front Med (Lausanne) 9: 960235.

- Jung J, Hwang S, Hong S (2019) Long-term postresection prognosis of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the liver. Ann Surg Treat Res 97: 176-183.

- Popescu G, Alexandrescu ST, Grigorie RT, Stoica L, Apavaloaie CA, et al. (2017) GOOD TO KNOW: The ALPPS Procedure - Embracing a New Technique. Chirurgia (Bucur) 112: 332-341.

- Yang P, Huang X, Lai C (2019) SET domain containing 1B gene is mutated in primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer 145: 2986-2995.

- Li R, Zhao J, Rao S, Chen C, Zeng M, et al. (2013) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: MR imaging findings including preliminary observation on diffusion-weighted imaging. Abdom Imaging 38: 1269-1276.

- Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D (2020) The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 76: 182-188.

- Hu H, Yu T (2019) Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 98: e18278.

- Kim JE, Lee WJ, Kim SH, Rhim H, Song HJ, et al. (2011) Three-phase helical computed tomographic findings of hepatic neuroendocrine tumors: pathologic correlation with revised WHO classification. J Comput Assist Tomogr 35: 697-702.

- Haupt F, Afshar-Oromieh A, Obmann VC, Huber AT, Maurer M (2021) Cystic Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: A Rare Entity. Clin Nucl Med 46: e577-e578.

- Torbenson M, Venkatesh SK, Halfdanarson TR, Navin PJ, Kamath P, et al. (2023) Primary neuroendocrine tumors and primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the liver: a proposal for a multidiscipline definition. Hum Pathol 132: 77-88.

- Caplin ME, Buscombe JR, Hilson AJ, Jones AL, Watkinson AF, et al. (1998) Carcinoid tumour. The Lancet 352: 799-805.

- Li Y, Zhang Q, Wang W (2020) Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Outcomes of Primary Hepatic Neuroendocrine Tumor: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Population-Based Study. Med Sci Monit 26: e923375.

- Bouzayan L, Madani A, Malki S (2022) Primary hepatic origin of a neuroendocrine tumor: A rare case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 84: 104937.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.