Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma Mimicking Angioedema: Case Report and Brief Literature Review

by Jieun Yang1, Jieun Park1, Sanghoon Han1, Chi Wha Han1, Sang Taek Heo1, Jae Wang Kim2, Jaemin Jo1*

1Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, Korea

2Department of Dermatology, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, Korea

*Corresponding author: Jaemin Jo, Department of Internal Medicine, Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju National University School of Medicine & College of medicine 15, Aran 13-gil, Jeju-si Jeju-do, 63241, Republic of Korea.

Received Date: 29 July, 2024

Accepted Date: 14 August, 2024

Published Date: 17 August, 2024

Citation: Yang J, Park J, Han S, Han CW, Heo ST, et al. (2024) Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell Lymphoma Mimicking Angioedema: Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Clin Exp Dermatol Ther 9: 226. https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-8268.100226

Abstract

Various medical conditions that cause subcutaneous swelling can mimic angioedema, and appropriate differential diagnosis is sometimes challenging for clinicians because of its relative rarity. We herein report a case of a 38-year-old man with primary subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma that was initially misdiagnosed as angioedema because of the patient’s prominent facial swelling. Our experience shows that not all facial edema are angioedema and reinforces the importance of clinical suspicion, appropriate evaluation, and treatment for patients with an atypical presentation of facial swelling.

Keywords:Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; Primary Cutaneous Lymphoma; Atypical Facial Swelling; Pseudoangioedem.

Introduction

Angioedema is a localized, temporary swelling of the skin and/or mucosal tissues due to extravasation of intravascular fluid into the interstitium and mainly involves the facial, gastrointestinal, and respiratory mucosa. It is a relatively common emergency medical condition affecting the airways. Angioedema can be classified by its underlying mechanisms: histaminergic and bradykinin-mediated angioedema [1], and clinicians should apply proper therapeutic and diagnostic approaches according to the underlying pathophysiology.

Many medical conditions that manifest as facial swelling are mistaken for angioedema, including contact dermatitis, hypothyroidism, and soft tissue infections. Hence, clinicians should be aware of the differential diagnosis of angioedema because an inappropriate treatment approach can be fatal [2-4].

Lymphoproliferative disease (LPD) can cause angioedema via a bradykinin-mediated mechanism in the form of acquired angioedema that occurs in relation to C1 esterase inhibitor (C1 INH) dysfunction, but it rarely mimics angioedema due to facial edema with skin involvement [1,3].

We here in report a case of a patient with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) and related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocystosis (HLH) that was initially misdiagnosed as angioedema, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Case report

A 38-year-old male patient visited the emergency department with complaints of facial edema and fever that started 2 weeks previously. He also experienced spontaneous resolution of chest wall nodules and bilateral proximal arms edema 2 months ealier. The patient was given steroids, antihistamines, antibiotics, and omalizumab for suspected angioedema, but he showed minimal response, and the facial swelling gradually progressed (Figure 1A). The facial swelling mainly involved the periorbital and lip areas with a harder woody nature, but not the tongue or upper airway. The periorbital swelling was accompanied by purpuric discoloration. Multifocal, deep-seated, infiltrative, erythematous, non-tender nodulopapules were also present in the trunk and both arms (Figure 1B). He had persistent fever and poor appetite, but he did not have other systemic symptoms such as itching, dyspnea, wheezing, abdominal pain, joint swelling, recurrent oral ulcers, or proximal muscle weakness. It was the patient’s first time to experience such symptoms, and he denied any specific family history of angioedema. He had taken dexibuprofen and amoxicillin-clavulanate 2 months previously, but the symptoms progressed despite discontinuation. His vital signs were the following: blood pressure, 121/59 mmHg; pulse rate, 96 bpm; respiration rate, 20 cycles/min; body temperature, 38.7°C.

Figure 1: (A) Severe facial swelling mainly involving the eyes and lips, and periorbital swelling with purpuric discoloration; (B) Multiple erythematous nodulopapules with infiltrative nature involving both arms and the trunk; (C-D) Facial swelling and infiltrative cutaneous lesions disappeared. Only discoloration and desquamation remained in both arms.

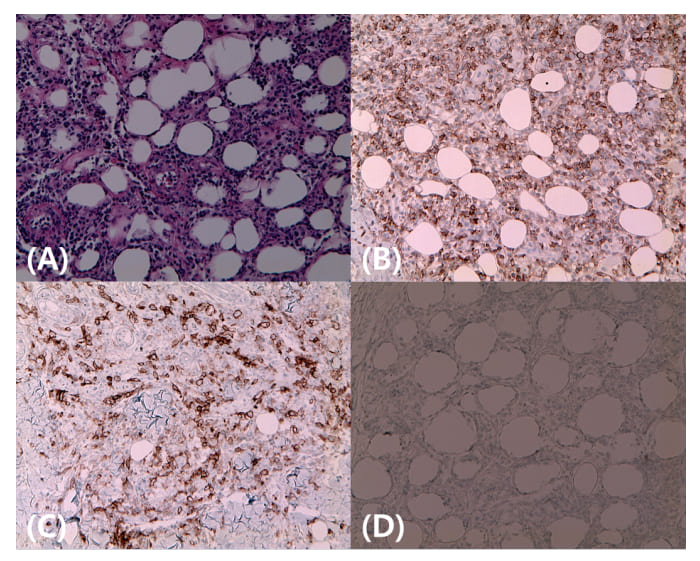

No lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly were observed. Laboratory findings revealed mild leukopenia (2000/mL), anemia (12.5 g/dL), elevated aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase (148 and 67 IU/L, respectively), and elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (976 U/L). Autoimmune markers, including antinuclear antibody, complement level, myoglobin, immunoglobulin (Ig) level, and microbiological test results were all unremarkable. Based on the atypical presentation, a skin biopsy was immediately performed on the periorbital area and forearm. Pathological examination showed perivascular and interstitial atypical lymphoid cell infiltration involving subcutaneous fat (Figure 2A), and immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor cells highly expressed CD3 and CD8 but did not express CD30 or CD56, suggesting the possibility of SPTCL (Figure 2B-2D).

Figure 2: (A) Microscopically, neoplastic atypical lymphocytic perivascular and interstitial infiltration in subcutaneous fat with angio-destruction; (B-D) Tumor cells showing positive immunoreactivity for CD3 (B) and CD8 (C) and negative immunoreactivity for CD 30 (D).

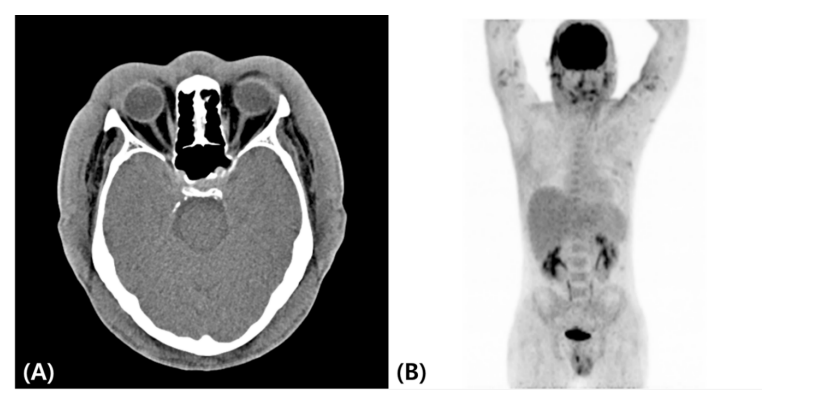

A computed tomography (CT) scan from the craniofacial area to the pelvis showed splenomegaly and diffuse soft tissue swelling of the head, face, neck, and trunk (Figure 3A). Positron emission tomography CT revealed metabolic uptake along the face, both upper and lower extremities, and the cutaneous area of the trunk (Figure 3B). A subsequent study revealed the presence of HLH, including bone marrow hemophagocytosis, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperferritinemia, elevated soluble interleukin 2 receptor alpha levels, and low natural killer cell activity. Other laboratory studies showed minimal IgG monoclonal gammopathy and negative blood Epstein-Barr virus test results.

Figure 3: Computed tomography image showing diffuse craniofacial soft tissue swelling; (A) Positron emission tomography–computed tomography image showing mild to moderate metabolic uptake along the cutaneous areas of the face, both upper and lower extremities, and the trunk (B).

We administered cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) combination chemotherapy and further tested T-cell receptor (TCR) beta, delta, and gamma rearrangement using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to differentiate primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma with similar clinical features but significantly different prognoses.

Results

The facial swelling and cutaneous lesions responded quickly after chemotherapy, and his clinical signs, symptoms, and laboratory results completely normalized after six cycles of CHOP combination chemotherapy (Figure 1C-D). We confirmed SPTCL through TCR rearrangement PCR results, which showed clonality; thus, we did not proceed with consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation.

Discussion

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) are a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that are present on the skin without evidence of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis. PCLs can be divided into the more common primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL; 75%-80%) and the less common primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (20%-25%) [5]. The characteristics, treatment strategies, and prognosis vary substantially among several types of PCLs. SPTCL is a rare subtype of CTCL, accounting for less than 1% of all peripheral T-cell lymphomas [6].

In 2005, the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification classified original SPTCL with only the alpha-beta T-cell phenotype as SPTCL and the gamma-delta T-cell phenotype as primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma based on different clinical and histological features [7]. The median age at diagnosis was 36 years, and it typically presents as one or more painless and poorly demarcated subcutaneous nodules involving the extremities, trunk, or face. Secondary HLH is less common in SPTCL (17%) than that for primary cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (50%) and is associated with poor survival outcome [8]. Skin lesions are usually misdiagnosed as panniculitis or other cutaneous diseases; therefore, histological examination is required to confirm the diagnosis.

A typical histological finding is the presence of dense subcutaneous atypical lymphocytes sparing the septa, dermis, and epidermis. Neoplastic cells express CD3, CD8, and alpha-beta TCR but not CD4, CD56, or CD30 [6,8,9]. Specific treatment guidelines are lacking owing to its rarity and range from a single immunosuppressive agent to combination chemotherapy with or without stem cell transplantation. Single immunosuppressive agents such as steroids, cyclosporine, and methotrexate are usually recommended for patients with an indolent disease course, and aggressive treatment with chemotherapy and/or stem cell transplantation may be considered for patients with an aggressive disease course, multiple relapses, or concomitant HLH [5,6,8-10].

Angioedema typically affects areas with loose connective tissue, such as the face, airway and gastrointestinal mucosa, extremities, and genitalia. It is characterized by an acute onset, self-limiting course, asymmetric distribution, and involvement of non-gravitational areas. Urticaria, wheals, and triggering factors are the main features of histamine-mediated angioedema lymphoid malignancy. Rare but well-known angioedema related to LPD is acquired angioedema (AAE), and C1 INH dysfunction is suggestive of the underlying pathogenesis. AAE begins after the age of 40 years in 94% of patients, and patients have no family history of angioedema. The clinical features are similar to those of hereditary angioedema, but gastrointestinal involvement is less common, similar to hereditary angioedema. AAE treatment includes treatment of acute angioedema attacks, prevention of recurrence, and treatment of the underlying disease [11].

Various nonspecific diseases accompanied by subcutaneous swelling can be mistaken for angioedema and are therefore called “pseudoangioedema” in the literature. LPD should also be considered a disease that causes pseudoangioedema [2,3,4,12]. Cases of LPD with angioedema or pseudoangioedema unrelated to C1 INH dysfunction are rare (Table 1) [13-17]. The cases reported by Harrison et al. and Patel et al. [13,14] were related to vasoactive agent release from the skin involved in peripheral T-cell lymphoma and may be suggestive of histamine-mediated angioedema. Edema in these patients was characterized by spontaneous resolution but with recurrence, accompanying urticarial rash, and antihistamine or steroid responsiveness [13,14]. The cases we presented and those reported by Fricker et al. and Yeh et al. demonstrated pseudoangioedema associated with skin involvement in LPD, and they showed a progressive and persistent course, symmetrical distribution, accompanying skin manifestations, and no antihistamine or steroid responsiveness [16,17].

|

Authors |

Age (years)/sex |

Clinical features |

Diagnosis |

Mechanism |

Skin involvement |

Laboratory finding |

Antihistamine/steroid response |

Treatment |

Outcome |

|

Harrison et al. [13] |

60/female |

Intermittent, spontaneous resolved edema, Progressive swelling from tongue to general area, Urticarial rash Subcutaneous nodule |

PTCL |

Vasoactive substance release by cutaneous lymphoma cells |

Yes |

Normal C1 INH, C3 level |

Yes |

Combination chemotherapy |

Death after relapse |

|

Patel et al. [14s] |

56/male |

Spontaneous resolution within 1-2 days initially, but became progressive, then fixed, and the course was unresolved Swelling began from the chest to the face, Urticarial rash |

PTCL |

Vasoactive substance release by cutaneous lymphoma cells |

Yes |

Normal C1q, C1 INH level |

Minimal |

Omit due to poor general condition |

Death from disease progression |

|

Bidkar et al. [15] |

52/male |

Orolingual swelling, Low-grade fever Urticaria without rash |

AITL |

Unknown mechanism of paraneoplastic feature |

Unknown |

Normal C1q, C2 INH level |

Yes |

Chemotherapy |

Free from disease |

|

Fricker et al. [16] |

38/male |

Progressive and persistent, Asymmetric, flocculating, disfiguring, and indurated facial swelling, No rash or urticaria |

SPTCL |

Pseudoangioedema related to skin involvement |

Yes |

Normal C1 INH, C4, tryptase level |

No |

Combination chemotherapy |

Free from disease |

|

Yeh et al. [17] |

54/male |

Diffuse lip swelling with overlying papules for 2 years |

SLL |

Pseudoangioedema related to skin involvement |

Yes |

Not available |

Yes |

Radiotherapy |

Relapse and remission after topical imiquimod treatment |

|

Present case |

38/male |

Persistent and progressive, Asymmetric, non-pitting, and with accompanying discoloration swelling, Swelling began from the upper extremities to the face, Nodulopapules involving the trunk and upper extremities, Persistent fever |

SPTCL |

Pseudoangioedema related to skin involvement |

Yes |

Normal complement level |

No |

Combination chemotherapy |

Free from disease |

Table 1: Literature review of case reports with lymphoproliferative disease presenting with angioedema or pseudoangioedema unrelated to C1 INH dysfunction; C1 INH, C1 esterase inhibitor; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; AITL; angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; SPTCL, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Our patient was initially misdiagnosed with angioedema because of the prominent facial swelling, which led to inappropriate treatment and progression to advanced-stage SPTCL with HLH. This patient exhibited clinical features distinct from true angioedema, including a prolonged and resistant course lasting more than 2 weeks; lack of involution and progression of lesions over time; poor response to treatment with antihistamines, steroids, and omalizumab; absence of typical features such as wheals or pruritus associated with histamine-mediated angioedema; no involvement of gastrointestinal edema, mucosal edema, or laryngeal edema typical of angioedema; palpation revealing a woody, harder infiltration rather than a soft, doughy texture, which raised suspicion of a neoplastic disorder; and accompanying systemic symptom, including fever and general weakness. If detailed history taking and physical examinations were conducted based on this, appropriate diagnosis and treatment could have been attempted earlier and at a less-advanced stage of the disease. There may be controversy on the appropriate treatment for the patient, but because HLH was present and primary cutaneous gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma could not be ruled out initially, CHOP combination chemotherapy was attempted, and good treatment results were obtained.

Conclusion

We reported a case of SPTCL with prominent facial swelling that presented as pseudoangioedema. It is advisable to refrain from uniformly treating all patients who come to the hospital with facial swelling as angioedema and to provide appropriate diagnosis and treatment in cases with atypical presentation through a careful approach and active diagnostic attempts, including histological examination.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Kanani A, Betschel SD, Warrington R (2018) "Urticaria and Angioedema." Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2: 59.

- Weldon D (2006) "Differential Diagnosis of Angioedema." Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 26: 603-613.

- Sevgi A, Ecem C (2017) "Pseudoangioedema."

- Andersen MF, Longhurst HJ, Eva Rasmussen R, Bygum A (2016) "How Not to Be Misled by Disorders Mimicking Angioedema: A Review of Pseudoangioedema." Int Arch Allergy Immunol 169: 163-170.

- Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M, et al. (2018) "Primary Cutaneous Lymphomas: Esmo Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up." Ann Oncol 29: iv30-iv40.

- Alsomali DY, Bakshi N, Kharfan-Dabaja M, Fakih RE, Aljurf M (2023) "Diagnosis and Treatment of Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T-Cell Lymphoma: A Systematic Literature Review." Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 16: 110-116.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, et al. (2005) "Who-Eortc Classification for Cutaneous Lymphomas." Blood 105: 3768-3785.

- Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, Santucci M, Assaf C,et al. (2008) "Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T-Cell Lymphoma: Definition, Classification, and Prognostic Factors: An Eortc Cutaneous Lymphoma Group Study of 83 Cases." Blood 111: 838-845.

- Lin EC, Liao JB, Fang YH, Hong CH (2023) "The Pathophysiology and Current Treatments for the Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T Cell Lymphoma: An Updated Review." Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 19: 27-34.

- Stuver R, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Horwitz SM (2023) "Few and Far Between: Clinical Management of Rare Extranodal Subtypes of Mature T-Cell and Nk-Cell Lymphomas." Haematologica 108: 3244-3260.

- Cicardi M, Aberer W, Banerji A, Bernstein JA, Bork K, et al. (2014) "Classification, Diagnosis, and Approach to Treatment for Angioedema: Consensus Report from the Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group." Allergy 69: 602-616.

- Fok, JS, Katelaris CH (2019) "Angioedema Masqueraders." Clin Exp Allergy 49: 1274-1282.

- Harrison NK, Twelves C, Addis BJ, Taylor AJ, Souhami RL, et al. (1988) "Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Presenting with Angioedema and Diffuse Pulmonary Infiltrates." Am Rev Respir Dis 138: 976-980.

- Patel S, Patel R, Draikiwicz S, Capitle E (2015) "Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: A Challenging Mimicker of Angioedema and Urticaria." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 115: 94-95.

- Bidkar VG, Rajan NR, Dasar S, Naik AS, Rao R, et al. (2019) "Acquired Angioedema: A Rare Manifestation of Angioimmunoblastic T Cell Lymphoma." Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 71: 96-99.

- Fricker M, Dubach P, Helbling A, Diamantis E, Villiger PM, et al.(2015) "Not All Facial Swellings Are Angioedemas!" J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 25:146-147.

- Yeh JE, Lorenzo ME, Larocca C, Fisher DC, Foreman RK (2022) "Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma Presenting as Chronic Diffuse Lip Swelling." Dermatol Online J 28.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.