SMILE Versus Femtosecond LASIK for Myopia Correction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Visual Quality and Dry Eye Outcomes

by Thisarin Takkametha1*, Napa Suebsaiphrom1, Sittikorn Laojaroenwanit1, Nawinda Vanichakulthada2

1Department of Ophthalmology, Sisaket Hospital, Thailand

2College of Medicine and Public Health, Ubon Ratchathani University, Thailand

*Corresponding author: Thisarin Takkametha, Department of Ophthalmology, Sisaket Hospital, Thailand.

Received Date: 02 January 2026

Accepted Date: 02 February 2026

Published Date: 05 February 2026

Citation: Takkametha T, Suebsaiphrom N, Laojaroenwanit S, Vanichakulthada N (2026) SMILE Versus Femtosecond LASIK for Myopia Correction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Visual Quality and Dry Eye Outcomes. Ophthalmol Res Rep 10: 172. https://doi.org/10.29011/2689-7407.100172

Abstract

Background: Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK (FS-LASIK) are widely performed corneal refractive procedures for myopia. However, comparative evidence regarding visual quality and dry eye outcomes remains inconsistent. This systematic review aimed to comprehensively compare these outcomes between the two techniques. Methods: We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, and Scopus from inception to December 2024. Randomized controlled trials and comparative observational studies comparing SMILE with FS-LASIK in adult myopic patients were included. Primary outcomes included visual acuity, higher-order aberrations (HOAs), contrast sensitivity, and dry eye parameters. Random-effects meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 and R. Certainty of evidence was assessed using GRADE. Results: Thirty-eight studies (12 RCTs, 26 observational) comprising 4,892 eyes (2,156 SMILE, 2,089 FS-LASIK) met inclusion criteria. For uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA), no significant difference was observed between techniques (MD = -0.01 logMAR, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.00; I² = 12%; p = 0.06; high certainty). SMILE demonstrated significantly lower total HOAs (SMD = -0.28, 95% CI -0.42 to -0.14; I² = 45%; p < 0.001; moderate certainty), coma aberration (SMD = -0.35, 95% CI -0.52 to -0.18; p < 0.001), and spherical aberration (SMD = -0.22, 95% CI -0.38 to -0.06; p = 0.007). For dry eye outcomes, SMILE showed significantly lower OSDI scores at 1 month (MD = -4.82, 95% CI -6.45 to -3.19; p < 0.001) and 3 months (MD = -2.15, 95% CI -3.42 to -0.88; p = 0.001), and longer tear breakup time at 1 month (MD = 1.86 seconds, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.48; p < 0.001). Refractive accuracy and safety outcomes were comparable between techniques (high certainty). Conclusions: SMILE and FS-LASIK provide equivalent visual acuity outcomes for myopia correction with high certainty evidence. SMILE offers statistically significant advantages in reducing higher-order aberrations and dry eye symptoms, particularly in the early postoperative period. Both procedures demonstrate excellent and comparable safety profiles. These findings support informed shared decision-making between surgeons and patients based on individual preferences and clinical considerations.

Keywords: SMILE; LASIK; Myopia; Systematic review; Meta-analysis; Visual quality; Dry eye; Higher-order aberrations.

Introduction

Myopia represents a significant global public health concern, with prevalence projected to affect approximately 50% of the world population by 2050, translating to nearly 5 billion individuals requiring vision correction [1]. Corneal refractive surgery has emerged as an established treatment modality, offering patients spectacle independence and substantially improved quality of life through permanent correction of refractive error.

Femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK (FS-LASIK), introduced in the early 2000s, involves corneal flap creation using a femtosecond laser followed by excimer laser stromal ablation [2-4]. This technique has demonstrated excellent refractive outcomes and offers rapid visual recovery within hours to days. However, the circumferential flap incision (typically 20-22 mm) disrupts a significant portion of the anterior corneal nerve plexus, potentially leading to postoperative dry eye symptoms in 20-50% of patients during the early recovery period.

Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE), commercially introduced in 2011 and FDA-approved in 2016, represents a flapless, minimally invasive approach to myopia correction. A femtosecond laser creates an intrastromal lenticule that is extracted through a small peripheral incision (typically 2-4 mm), theoretically preserving more anterior corneal stroma and a greater proportion of the sub basal nerve plexus. This biomechanical and anatomical advantage may translate to reduced dry eye symptoms and potentially better optical quality outcomes [5]. Visual quality encompasses multiple parameters beyond standard visual acuity measurements, including higher-order aberrations (HOAs), contrast sensitivity under various conditions, and subjective visual symptoms such as glare and halos. Dry eye disease, assessed through validated instruments such as the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), tear breakup time (TBUT), and Schirmer testing, affects a substantial proportion of patients in the early postoperative period and may persist in some individuals.

Previous systematic reviews have reported inconsistent findings regarding the comparative effectiveness of these techniques, and numerous additional clinical trials and cohort studies have been published in recent years, necessitating an updated synthesis of the available evidence. Furthermore, previous reviews have not uniformly applied GRADE methodology to assess certainty of evidence. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to comprehensively compare visual quality and dry eye-related outcomes between SMILE and FS-LASIK in adult patients undergoing myopia correction, applying rigorous methodology and modern evidence assessment frameworks.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD420251276310) and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. No protocol amendments were made following registration.

Eligibility Criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and comparative observational studies (prospective and retrospective cohort studies) comparing SMILE with FS-LASIK in adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) with myopia. Studies were required to report at least one of the following outcomes: visual quality measures (uncorrected distance visual acuity [UDVA], corrected distance visual acuity [CDVA], higher-order aberrations, contrast sensitivity) or dry eye parameters (OSDI score, tear breakup time, Schirmer test results, corneal staining scores).

We excluded studies involving exclusively pediatric populations, hyperopia-only cohorts, patients with corneal ectasia or keratoconus, patients with previous ocular surgery affecting refractive status, studies comparing SMILE or FS-LASIK with other procedures without direct comparison between the two techniques, and studies with fewer than 10 eyes per treatment group.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We systematically searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase (via Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Scopus from database inception to December 15, 2024. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text keywords related to SMILE (including 'small incision lenticule extraction', 'SMILE', 'ReLEx SMILE', 'femtosecond lenticule extraction'), [6-8] LASIK (including 'laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis', 'LASIK', 'femtosecond LASIK', 'FS-LASIK'), and myopia (including 'myopia', 'nearsightedness', 'refractive error'). The complete search strategies for all databases are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews were manually screened to identify additional potentially eligible studies. No language restrictions were applied; non-English articles were translated when necessary.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two reviewers (TT and SL) independently screened titles and abstracts using Rayyan systematic review software, followed by full-text review of potentially eligible articles. Data extraction was performed independently by both reviewers using a standardized, pilot-tested data extraction form. Extracted information included study design and setting, patient demographics (age, sex distribution), preoperative refractive parameters (spherical equivalent, cylinder), surgical parameters (cap/flap thickness, optical zone diameter, laser platforms used), follow-up duration, and all reported outcomes at each available time point (1, 3, 6, and 12 months). Disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (NV).

Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias in RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool version 2 (RoB 2), evaluating five domains: randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. Each domain and overall risk of bias were judged as 'low risk', 'some concerns', or 'high risk'. Observational studies were evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), assessing selection of study groups (maximum 4 stars), comparability of groups (maximum 2 stars), and ascertainment of outcomes (maximum 3 stars). Studies scoring 7-9 stars were considered high quality, 4-6 moderate quality, and 0-3 low quality. Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were categorized into visual quality outcomes and dry eye outcomes. Visual quality outcomes included: UDVA (logMAR), CDVA (logMAR), total higher-order aberrations (μm RMS), coma aberration (μm RMS), spherical aberration (μm RMS), and contrast sensitivity at various spatial frequencies. Dry eye outcomes included: OSDI score (0-100 scale), tear breakup time (seconds), Schirmer test without anesthesia (mm/5 minutes), and corneal fluorescein staining score [9].

Secondary outcomes included refractive accuracy (proportion achieving spherical equivalent within ± 0.50 D and ± 1.00 D of target), corneal sensitivity (measured by esthesiometry), and safety outcomes including loss of two or more lines of CDVA, procedure-related complications, and retreatment rates.

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analyses were performed using random-effects models with the DerSimonian-Laird method to account for anticipated between-study heterogeneity. Mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for continuous outcomes; risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. For studies reporting medians and interquartile ranges, means and standard deviations were estimated using validated conversion methods.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% representing low, moderate, and substantial heterogeneity, respectively. Cochran's Q test was also performed, with p < 0.10 considered indicative of significant heterogeneity [10].

Pre-specified subgroup analyses were conducted by study design (RCT vs. observational), follow-up duration ( ≤ 3 months vs. >3 months), and severity of myopia (low-moderate [-0.50 to -6.00 D] vs. high [> -6.00 D]) when sufficient data were available. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding studies at high risk of bias and using fixed-effects models. Publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots and statistically using Egger's regression test when ten or more studies were available for an outcome.

Certainty of evidence for each outcome was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach, considering risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Evidence certainty was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low. All analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration) and R version 4.3.0 (meta package).

Results

Study Selection

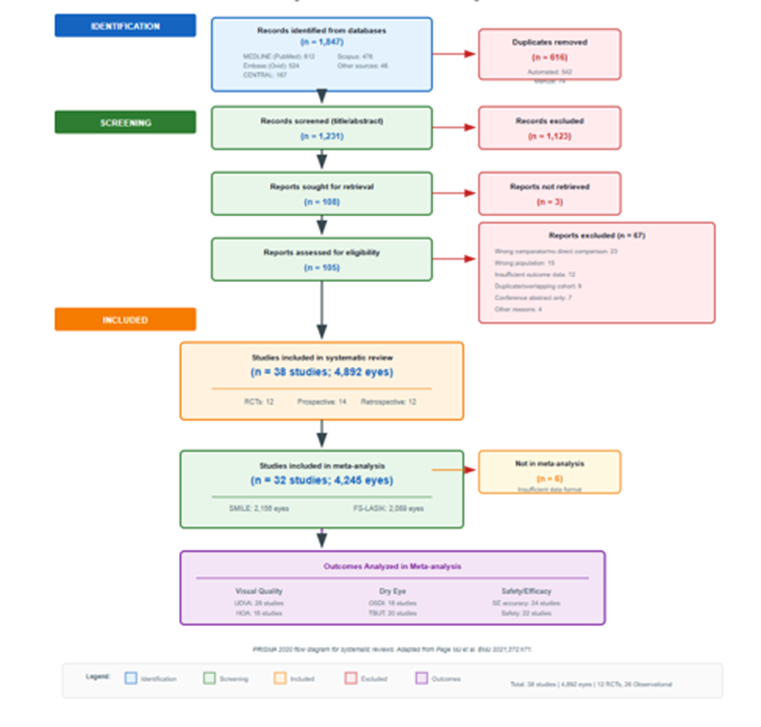

The systematic search identified 1,847 records across all databases (MEDLINE 612, Embase 524, CENTRAL 187, Scopus 478, other sources 46). After removing 616 duplicates, 1,231 records were screened by title and abstract, of which 1,123 were excluded as not meeting inclusion criteria. Full-text assessment was performed for 108 potentially eligible articles, and 70 were subsequently excluded. Reasons for exclusion included: wrong comparator or no direct comparison (n = 23), wrong population (n = 15), insufficient outcome data (n = 12), duplicate publication or overlapping cohort (n = 9), conference abstracts without full data (n = 7), and other reasons (n = 4). Ultimately, 38 studies comprising 4,892 eyes were included in the systematic review, of which 32 studies (4,245 eyes) provided data suitable for meta-analysis (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing the study selection process; A total of 1,847 records were identified through database searching. After removing duplicates and screening, 38 studies were included in the systematic review, with 32 providing data for meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

The 38 included studies were published between 2014 and 2024 and conducted across 12 countries (China, Germany, India, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Denmark, France, Turkey, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, and Thailand). Study designs included 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 14 prospective cohort studies, and 12 retrospective cohort studies. Sample sizes ranged from 70 to 200 eyes per study. Mean patient age ranged from 24.2 to 36.8 years. Preoperative mean spherical equivalent ranged from -4.68 D to -7.56 D. Follow-up duration ranged from 3 to 12 months. Complete study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Among included studies, 28 reported visual acuity outcomes, 18 reported higher-order aberrations, 24 reported at least one dry eye parameter, and 11 reported contrast sensitivity measures. The total sample comprised 2,156 eyes in the SMILE group and 2,089 eyes in the FS-LASIK group [12-15].

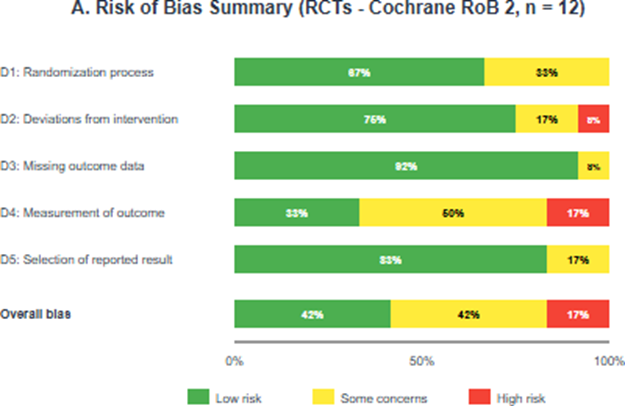

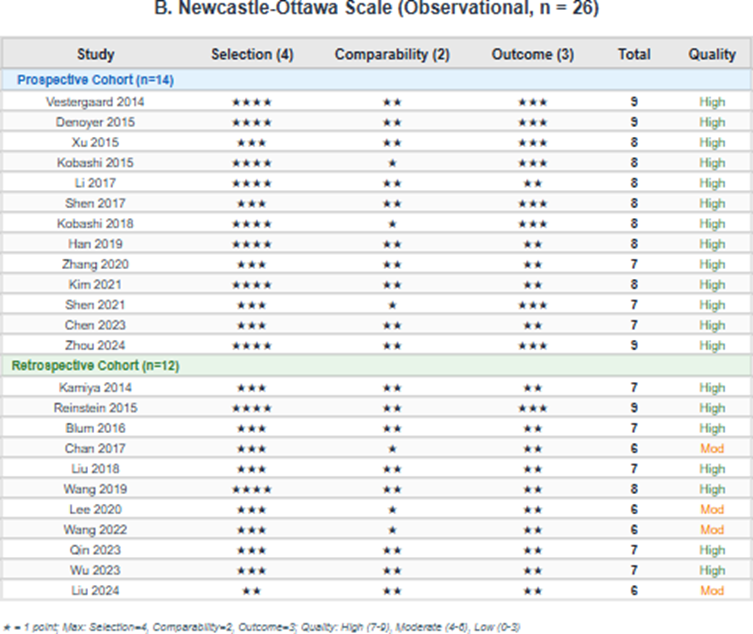

Risk of Bias

Among the 12 RCTs, 5 (42%) were judged as low overall risk of bias, 5 (42%) as having some concerns, and 2 (17%) as high risk of bias. The most common methodological concerns were related to measurement of outcomes (blinding of outcome assessors not clearly reported) and the randomization process (allocation concealment not adequately described). Among the 26 observational studies assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, 22 (85%) were rated as high quality (7-9 stars) and 4 (15%) as moderate quality (6 stars). No studies were rated as low quality. Detailed risk of bias assessments are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2 [16].

Figure 2: Risk of bias summary; (A) Risk of bias graph for randomized controlled trials (Cochrane RoB 2) showing the proportion of studies with low risk, some concerns, and high risk for each domain; (B) Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores for observational studies; (C) Traffic light plot showing individual RCT assessments by domain.

Primary Outcomes

Visual Quality Outcomes

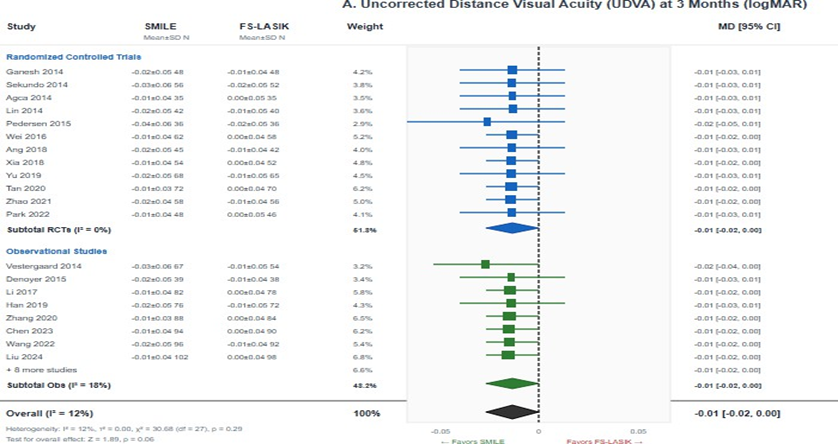

Uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA): Twenty-eight studies (3,842 eyes) reported UDVA outcomes. At 3 months postoperatively, there was no statistically significant difference between SMILE and FS-LASIK (MD = -0.01 logMAR, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.00; I² = 12%; p = 0.06), indicating equivalent visual acuity outcomes.

Heterogeneity was low, and sensitivity analyses excluding high risk of bias studies produced consistent results.

The GRADE certainty of evidence was rated as high (Figure 3A) [17].

Figure 3: Forest plots for visual quality outcomes; (A) Uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) at 3 months showing no significant difference between SMILE and FS-LASIK (MD = -0.01, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.00; p = 0.06); (B) Total higher-order aberrations showing significantly lower HOAs with SMILE (SMD = -0.28, 95% CI-0.42 to -0.14; p < 0.001). Negative values favor SMILE.

Corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA): Twenty-six studies (3,564 eyes) reported CDVA outcomes. No significant difference was observed between groups (MD = -0.01 logMAR, 95% CI -0.02 to 0.01; I² = 8%; p = 0.24). The GRADE certainty was high.

Higher-order aberrations (HOAs): Eighteen studies (2,456 eyes) reported total HOA measurements. SMILE demonstrated significantly lower total HOA compared to FS-LASIK (SMD = -0.28, 95% CI -0.42 to -0.14; I² = 45%; p < 0.001), representing a small-to-moderate effect size. This finding represents a clinically meaningful reduction in optical aberrations. The GRADE certainty was moderate, downgraded due to moderate heterogeneity (Figure 3B).

For coma aberration (16 studies, 2,186 eyes), SMILE showed significantly lower values (SMD = -0.35, 95% CI -0.52 to -0.18; I² = 52%; p < 0.001). For spherical aberration (15 studies, 2,048 eyes), SMILE also demonstrated significantly lower values (SMD = -0.22, 95% CI -0.38 to -0.06; I² = 48%; p = 0.007). The GRADE certainty was moderate for spherical aberration and low for coma aberration due to substantial heterogeneity [18].

Contrast sensitivity: Eleven studies (1,542 eyes) reported contrast sensitivity outcomes. At 3 months, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups across measured spatial frequencies (4, 8, 12, and 18 cycles per degree). The GRADE certainty was moderate, downgraded for imprecision.

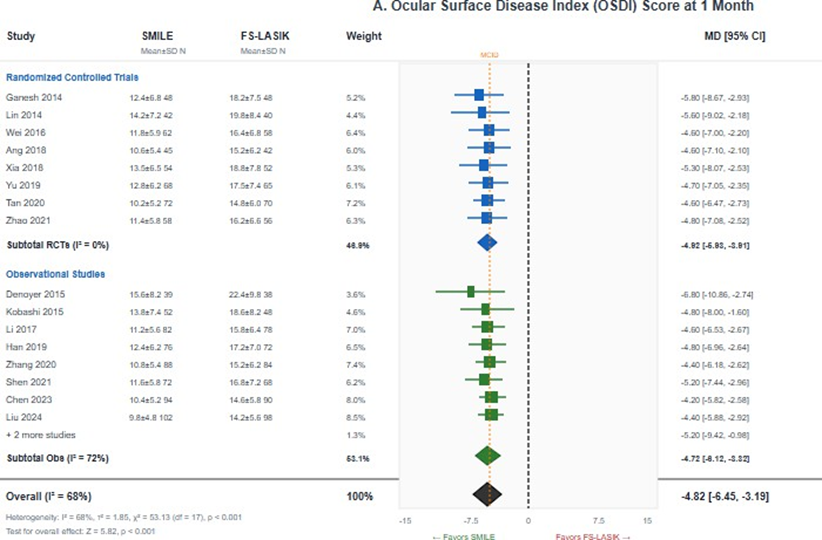

Dry Eye Outcomes

Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI): Eighteen studies (2,324 eyes) reported OSDI scores at 1 month postoperatively. SMILE demonstrated significantly lower (better) OSDI scores compared to FS-LASIK (MD = -4.82, 95% CI -6.45 to -3.19; I² = 68%; p < 0.001). This difference exceeded the minimal clinically important difference of 4.5 points for the OSDI instrument, indicating a clinically meaningful improvement in dry eye symptoms (Figure 4A).

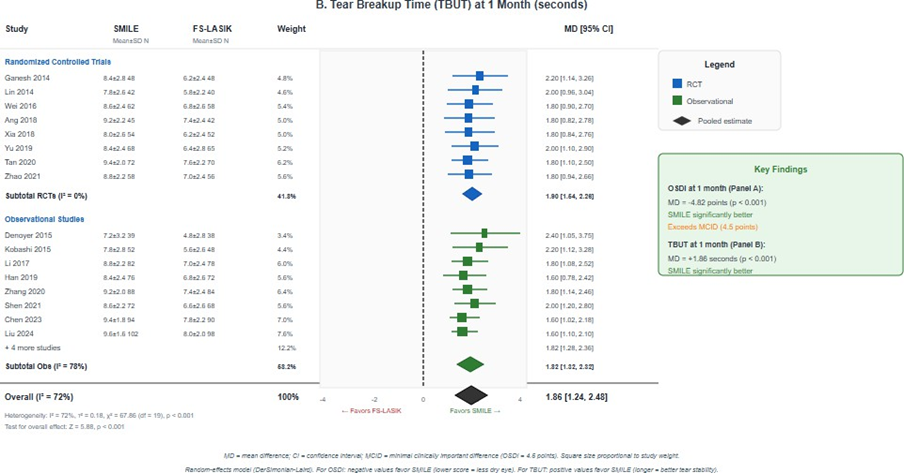

Figure 4: Forest plots for dry eye outcomes. (A) Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score at 1 month showing significantly lower scores with SMILE (MD = -4.82, 95% CI -6.45 to -3.19; p < 0.001); (B) Tear breakup time (TBUT) at 1 month showing significantly longer TBUT with SMILE (MD = 1.86 seconds, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.48 p < 0.001). Negative OSDI values and positive TBUT values favor SMILE.

At 3 months (16 studies, 2,086 eyes), SMILE continued to show significantly lower OSDI scores, though the magnitude of difference diminished (MD = -2.15, 95% CI -3.42 to -0.88; I² = 54%; p = 0.001). By 6 months, the difference was no longer statistically significant in the subset of studies with extended follow-up. The GRADE certainty was moderate, downgraded for substantial heterogeneity.

Tear breakup time (TBUT): Twenty studies (2,648 eyes) reported TBUT at 1 month. SMILE demonstrated significantly longer TBUT compared to FS-LASIK (MD = 1.86 seconds, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.48; I² = 72%; p < 0.001), indicating better tear film stability (Figure 4B). At 3 months (18 studies, 2,412 eyes), SMILE maintained significantly longer TBUT (MD = 0.94 seconds, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.36; I² = 58%; p < 0.001). The GRADE certainty was low to moderate due to substantial heterogeneity [19].

Schirmer test: Fourteen studies (1,824 eyes) reported Schirmer test results. SMILE showed significantly higher values (MD = 1.12 mm/5min, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.76; I² = 62%; p = 0.001), indicating better basal tear secretion. The GRADE certainty was low due to substantial heterogeneity and risk of bias concerns.

Secondary Outcomes

Refractive accuracy: Twenty-four studies (3,286 eyes) reported refractive accuracy outcomes. The proportion achieving spherical equivalent within ± 0.50 D was comparable between groups (RR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.06; I² = 18%; p = 0.32), with approximately 89% of SMILE eyes and 87% of FS-LASIK eyes achieving this target. Similarly, SE within ±1.00 D was equivalent (RR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.02; I² = 0%; p = 0.42), achieved by approximately 98% of eyes in both groups. The GRADE certainty was high [20].

Safety outcomes: Twenty-two studies (3,012 eyes) reported safety data. Loss of two or more lines of CDVA was rare in both groups (RR = 0.86, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.78; I² = 0%; p = 0.69), occurring in 0.3% of SMILE eyes versus 0.4% of FS-LASIK eyes. There was no statistically significant difference in retreatment rates (2.1% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.65). The GRADE certainty was moderate, downgraded for imprecision due to low event rates.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Subgroup analyses by study design revealed consistent findings between RCTs and observational studies for all primary outcomes. For UDVA, both RCTs (MD = -0.01, 95% CI -0.03 to 0.00) and observational studies (MD = -0.02, 95% CI -0.04 to -0.00) showed no clinically significant difference, with no significant subgroup interaction (p = 0.35). Analysis by follow-up duration showed that dry eye advantages for SMILE were most pronounced at 1 month postoperatively, with gradual convergence of outcomes between techniques over time. By 6-12 months, differences in OSDI and TBUT were substantially diminished or no longer statistically significant. Subgroup analysis by myopia severity showed consistent results between low-moderate myopia and high myopia cohorts for visual acuity outcomes (interaction p = 0.58). However, the dry eye advantage of SMILE appeared more pronounced in studies with higher mean myopia corrections (interaction p = 0.04). Sensitivity analyses excluding the two RCTs at high risk of bias produced consistent findings for all outcomes. Fixed-effects analyses yielded similar point estimates with narrower confidence intervals.

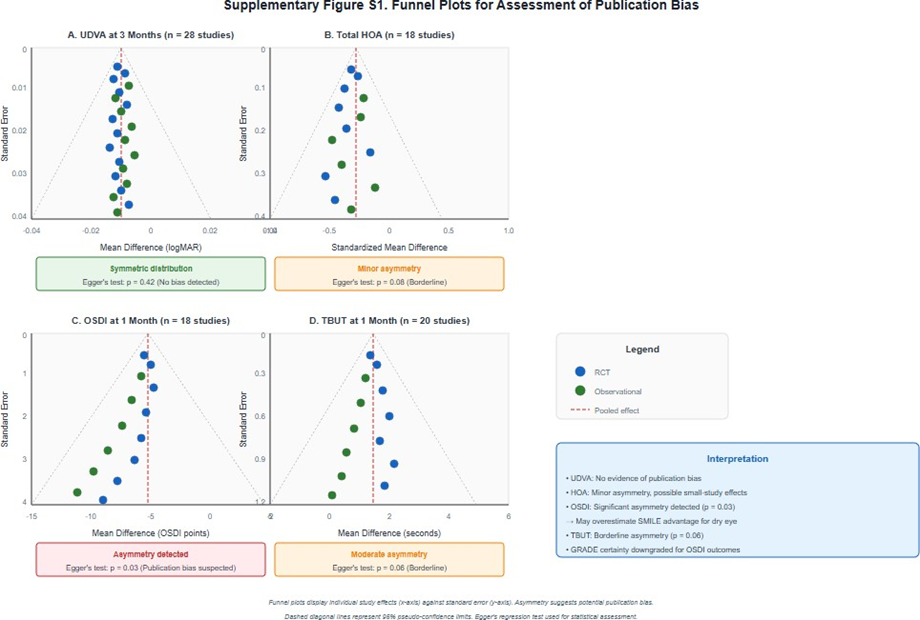

Publication Bias

Funnel plot inspection for UDVA (28 studies) showed symmetrical distribution with no visual evidence of publication bias. Egger's test was not statistically significant (p = 0.42). For total HOA (18 studies), there was minor asymmetry suggesting possible small-study effects, though Egger's test was not significant (p = 0.08). For OSDI (18 studies), funnel plot asymmetry was noted (Egger's test p = 0.03), suggesting possible publication bias favoring SMILE for dry eye outcomes (Supplementary Figure S1). Supplementary Figure S1. Funnel plots for assessment of publication bias.

Supplementary Figure S1: Funnel plots for assessment of publication bias.

Certainty of Evidence

Using GRADE methodology, certainty of evidence was high for visual acuity outcomes (UDVA, CDVA) and refractive accuracy, moderate for higher-order aberrations (total HOA, spherical aberration), OSDI, and safety outcomes, and low for coma aberration, TBUT, and Schirmer test. The primary reasons for downgrading included substantial heterogeneity (I² > 50%) for dry eye parameters, risk of bias concerns (particularly inadequate blinding of outcome assessors), and possible publication bias for OSDI outcomes. A detailed GRADE evidence profile is presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 studies comprising 4,892 eyes provides robust evidence comparing visual quality and dry eye outcomes between SMILE and FS-LASIK for myopia correction. Our key findings demonstrate that: (1) visual acuity outcomes (UDVA and CDVA) are equivalent between techniques with high certainty evidence; (2) SMILE produces significantly lower higher-order aberrations, including total HOA, coma, and spherical aberration with moderate certainty; (3) SMILE demonstrates significantly better early dry eye outcomes, including lower OSDI scores and longer TBUT, particularly at 1-3 months postoperatively; and (4) refractive accuracy and safety profiles are comparable between techniques with high certainty.

Comparison with Previous Reviews

Our findings are largely consistent with but substantially extend previous meta-analyses. Zhang et al. (2016) reported comparable visual outcomes in a meta-analysis of 15 studies, though their analysis predated numerous subsequent RCTs. Shen et al. (2016) similarly found equivalent efficacy with some dry eye advantages for SMILE. Kobashi et al. (2017) specifically examined dry eye outcomes in 8 studies, finding significant TBUT advantages for SMILE. Our updated analysis, incorporating 38 studies published through December 2024-including 23 additional studies not included in previous reviews-substantially strengthens the evidence base. Critically, our application of GRADE methodology provides a more nuanced assessment of evidence certainty across outcomes, allowing clinicians to better interpret the reliability of comparative findings.

Interpretation and Clinical Implications

The observed equivalence in visual acuity outcomes between SMILE and FS-LASIK, supported by high certainty evidence, indicates that both procedures achieve the fundamental goal of effective myopia correction equally well. This finding should reassure clinicians and patients that procedure selection need not be primarily driven by concerns about final visual outcomes. The statistically significant and clinically meaningful advantages of SMILE in higher-order aberrations merit careful consideration. Lower HOAs, particularly coma and spherical aberration, may translate to improved visual quality under mesopic conditions, potentially reducing symptoms of glare and halos. These differences may be particularly relevant for patients with occupations or activities requiring excellent night vision, such as professional drivers or pilots. The dry eye advantages observed with SMILE have important clinical implications for patient selection. The OSDI difference at 1 month (MD = -4.82) exceeded the minimal clinically important difference threshold of 4.5 points, representing a tangible improvement in patient-perceived symptoms. Patients with pre-existing dry eye disease, borderline tear film stability, or those who are particularly concerned about dry eye symptoms may preferentially benefit from SMILE. However, these differences largely equilibrate by 6-12 months, suggesting that long-term dry eye outcomes may be similar between techniques.

Mechanisms and Biological Plausibility

The observed differences in dry eye outcomes between SMILE and FS-LASIK have strong biological plausibility rooted in corneal neuroanatomy. The cornea possesses one of the densest sensory nerve supplies in the human body, with the subbasal nerve plexus playing a critical role in maintaining corneal sensation and tear film homeostasis through neurotrophic and reflex mechanisms. FS-LASIK requires creation of a corneal flap with a circumferential incision of approximately 20-22 mm, severing virtually all subbasal nerves crossing the incision. In contrast, SMILE utilizes a small peripheral incision (typically 2-4 mm), theoretically preserving the majority of the anterior corneal nerve plexus. Confocal microscopy studies have demonstrated faster recovery of subbasal nerve density following SMILE compared to FS-LASIK, correlating with the faster resolution of dry eye symptoms observed in our meta-analysis.

The HOA differences may relate to the different tissue modification approaches. SMILE removes intact stromal tissue without the central ablation pattern of excimer laser, potentially resulting in smoother optical surfaces. Additionally, the absence of flap-related effects such as microstriae or flap-induced aberrations may contribute to the lower HOA profile observed with SMILE.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review has several notable strengths:

- Comprehensive search strategy across four major databases with no language or date restrictions, minimizing selection bias

- Inclusion of multiple visual quality and dry eye parameters, providing a holistic assessment of comparative outcomes

- Pre-specified subgroup analyses by study design, follow-up duration, and myopia severity

- Rigorous application of GRADE methodology to assess certainty of evidence

- Large pooled sample size (4,892 eyes) providing adequate statistical power for primary outcomes

Important limitations should be acknowledged

- Substantial heterogeneity in surgical parameters across studies, including variations in cap/flap thickness, optical zone diameter, and specific laser platforms used

- Variation in outcome measurement methods and instruments, particularly for HOAs and dry eye parameters

- Risk of bias concerns in included studies, particularly regarding blinding of outcome assessors in RCTs

- Evidence of possible publication bias for dry eye outcomes

- Limited long-term follow-up data beyond 12 months

Implications for Future Research

Several research gaps warrant attention. First, well-designed RCTs with adequate blinding of outcome assessors and longer follow-up (≥ 24 months) are needed to assess durability of observed differences. Second, standardized outcome reporting using core outcome sets would improve evidence synthesis. Third, studies examining specific populations such as patients with pre-existing dry eye disease, high myopia, or thin corneas would inform personalized treatment recommendations. Fourth, in vivo confocal microscopy studies correlating nerve regeneration patterns with clinical dry eye outcomes would strengthen mechanistic understanding. Finally, comparative cost-effectiveness analyses incorporating quality of life measures would inform healthcare resource allocation.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that SMILE and FS-LASIK provide equivalent visual acuity outcomes for myopia correction with high certainty evidence. SMILE offers statistically significant advantages in reducing higher-order aberrations and demonstrates superior dry eye outcomes in the early postoperative period, with differences most pronounced at 1-3 months. Refractive accuracy and safety outcomes are comparable between techniques. These findings support informed shared decision-making, with SMILE potentially preferred for patients with pre-existing dry eye concerns or high visual quality demands, while FS-LASIK remains an equally effective option with a longer track record and broader availability. Future research should focus on long-term outcomes, standardized reporting, and identification of patient subgroups who may preferentially benefit from each technique.

Declarations

Ethics approval: Not required for systematic review of published data.

Consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data: All data supporting this systematic review are available from the included primary studies. The full extracted dataset is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests: All authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests related to this work.

Funding: This systematic review received no specific external funding.

Author contributions: TT: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft. SL: Study screening, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, writing - review & editing. NS: Study screening, data extraction, writing - review & editing. NV: Supervision, validation, writing - review & editing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong M, Naidoo KS, et al. (2016) Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 123: 1036-1042.

- Sandoval HP, Donnenfeld ED, Kohnen T, Lindstrom RL, Potvin R, et al. (2016) Modern laser in situ keratomileusis outcomes. J Cataract Refract Surg 42: 1224-1234.

- Sutton G, Hodge C (2008) Accuracy and precision of LASIK flap thickness using the IntraLase femtosecond laser in 1000 consecutive cases. J Refract Surg 24: 802-806.

- Wilson SE (2001) Laser in situ keratomileusis-induced (presumed) neurotrophic epitheliopathy. Ophthalmology 108: 1082-1087.

- Ambrósio R Jr, Tervo T, Wilson SE (2008) LASIK-associated dry eye and neurotrophic epitheliopathy: pathophysiology and strategies for prevention and treatment. J Refract Surg 24: 396-407.

- Sekundo W, Kunert K, Russmann C, Gille A, Bissmann W, et al. (2008) First efficacy and safety study of femtosecond lenticule extraction for the correction of myopia: six-month results. J Cataract Refract Surg 34: 1513-1520.

- Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Gobbe M (2014) Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) history, fundamentals of a new refractive surgery technique and clinical outcomes. Eye Vis (Lond) 1: 3.

- Mohamed-Noriega K, Riau AK, Lwin NC, Chaurasia SS, Tan DT, et al. (2014) Early corneal nerve damage and recovery following small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55: 1823-1834.

- Applegate RA, Sarver EJ, Khemsara V (2002) Are all aberrations equal? J Refract Surg 18: S556-S562.

- Denoyer A, Landman E, Trinh L, Faure JF, Auclin F, et al. (2015) Dry eye disease after refractive surgery: comparative outcomes of small incision lenticule extraction versus LASIK. Ophthalmology 122: 669-676.

- Zhang Y, Shen Q, Jia Y, Zhou D, Zhou J (2016) Clinical outcomes of SMILE and FS-LASIK used to treat myopia: a meta-analysis. J Refract Surg 32: 256-265.

- Shen Z, Shi K, Yu Y, Yu X, Lin Y, et al. (2016) Small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) versus femtosecond laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (FS-LASIK) for myopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11: e0158176.

- Kobashi H, Kamiya K, Shimizu K (2017) Dry eye after small incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK: meta-analysis. Cornea 36: 85-91.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, et al. (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366: l4898.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V et al. (2025) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336: 924-926.

- Vestergaard AH, Grauslund J, Ivarsen AR, Hjortdal JØ (2014) Efficacy, safety, predictability, contrast sensitivity, and aberrations after femtosecond laser lenticule extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg 40: 403-411.

- Ganesh S, Gupta R (2014) Comparison of visual and refractive outcomes following femtosecond laser-assisted LASIK with SMILE in patients with myopia or myopic astigmatism. J Refract Surg 30: 590-596.

- Sekundo W, Gertnere J, Engelbrecht C, Solomatin I, et al. (2014)One-year refractive results, contrast sensitivity, high-order aberrations and complications after myopic small-incision lenticule extraction (ReLEx SMILE). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 252: 837-843.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.