Sites of Recurrence in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Treated with Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

by Charalambos Mirelis1,3*, Dimitrios Kyziridis1, Apostolos Kalakonas1, Gregorios Tripsiannis2, Maria Drogouti3,4, Evripidis Efthymiou3, Antonios Apostolos Tentes1

1Department of Surgical Oncology, Euromedica Kyanous Stavros, Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Program, Viziis 1, Thessaloniki, Greece

2Department of Medicine, Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupoli, Greece

3Department of General Surgery, General Hospital of Thessaloniki “O Agios Dimitrios”, Elenis Zografou 2, Thessaloniki, Greece

4School of Medicine, European University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

*Corresponding Author: Charalampos Mirelis, Department of Surgical Oncology, Euromedica Kyanous Stavros, Peritoneal Surface Malignancy Program, Viziis 1, Thessaloniki, Greece

Received Date: 01 December 2025

Accepted Date: 05 December 2025

Published Date: 08 December 2025

Citation: Mirelis C, Kyziridis D, Kalakonas A, Tripsiannis G, Drogouti M, et al. (2025) Sites of Recurrence in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Treated with Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. J Surg 10:11505 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011505

Abstract

Introduction: Increased recurrence rate of epithelial ovarian cancer treated with current standard of care of cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy has led to an increasing use of hyperthermal intraperitoneal chemotherapy, not only in recurrent and chemo-resistant disease, but also in the setting of up-front treatment. Combination of cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy has shown some promising results.

Aims: A single-institutional, retrospective analysis of 239 women treated receiving the aforementioned treatment was conducted with primary aim of reporting recurrence site.

Patients and Methods: The incidence and anatomic distribution of recurrence in patients with ovarian cancer who underwent complete cytoreduction and HIPEC was retrospectively assessed. Clinical and pathological variables were analyzed in relation to Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS).

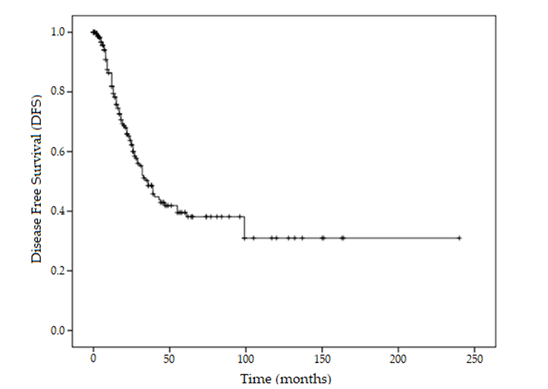

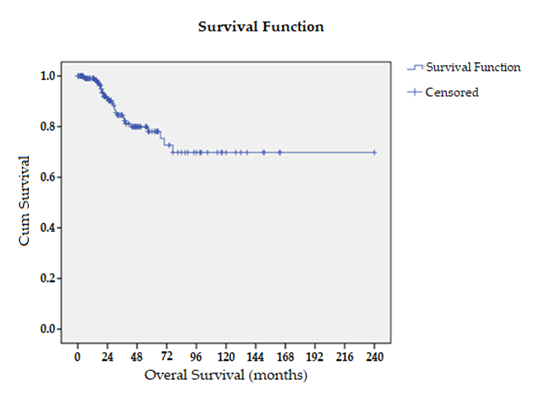

Results: From 2003 until 2023, 239 women underwent complete cytoreductive surgery, with HIPEC being performed in 192 (80.3%) of them. Recurrence occurred in 94 patients (39.3%). Distant and locoregional recurrence was almost equally distributed. The most frequently involved site of recurrence was the lymphatic network. The mean and median DFS was 95.7±9.8 (95% CI=6.51-114.85) and 36±4 months (95% CI=28.14-43.86). The 10-year DFS rate was 30.9%±5.2%. The overall survival rate at both 10 and 20 years was 70%.

Conclusions: In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer undergoing complete cytoreduction and HIPEC, the recurrence rate is 39.3%. Recurrence is equally distributed between distant and locoregional sites, with the lymph nodes being the most common location.

Keywords: Complete Cytoreduction; Hipec; Ovarian Cancer; Recurrence

Abbreviations: HIPEC: Hyperthermal Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy; OS: Survival; DFS: Disease Free Survival; CRS: Cytoreduction Surgery; NACT: Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PCI: Peritoneal Cancer Index; CC: Complete Cytoreduction; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; PARP: Poly ADP Ribose Polymerase; SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; FIGO: Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; PP: Peritonectomy Procedures; BU: Blood Units; FFP: Fresh Frozen Plasma; NSL: Number of Suture Lines; PSS: Prior Surgery Score; IV/IP: Intravenous/Intraperitoneal; BL: Blood Loss; DS: Duration of Surgery; REF: Reference; PS: Performance Status; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; TV: Tumor Volume; LNR: Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Resection; NA: Number of Anastomoses

Introduction

Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) followed by adjuvant systemic chemotherapy remains the standard of care for epithelial ovarian cancer [1]. Despite an initial favorable response, the majority of patients eventually experience recurrence. The 5-year survival rate remains below 30%, and the median Disease-Free Survival (DFS) is limited to approximately 18 months [2,3]. The introduction of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (NACT) has contributed in reducing peritoneal tumor burden, although it has not demonstrated any significant benefit in Overall Survival (OS) [4,5]. In recent years, prospective randomized trials have reported improved survival outcomes when Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) is incorporated into interval cytoreduction protocols [6,7]. Since 2018, CRS combined with HIPEC has gained popularity in the United States [8], not only in the setting of recurrent and chemo-resistant disease, but also as upfront treatment in selected patients, with encouraging results [9,10]. Although, its role remains controversial and not yet definitively established, HIPEC has recently been proposed in the international guidelines as an option in the treatment of ovarian cancer [8,11-13]. The most significant prognostic factor of long-term survival is considered the performance of complete cytoreduction [14,15]. However, even with advanced multimodal therapies, recurrence remains common and continues to pose a major clinical challenge. Gadducci et al. reported a recurrence rate of 73% after primary CRS followed by systemic chemotherapy, and 87.1% following interval cytoreduction [16]. Esselen et al. observed a 62.9% recurrence rate after optimal cytoreduction combined with intravenous and intraperitoneal chemotherapy [17]. According to Chambers et al., recurrence rates following interval and recurrent CRS with HIPEC were 55% and 49%, respectively [18], while Munoz-Casares et al. reported rates of 57% and 43% for primary and recurrent disease treated with CRS and HIPEC, respectively [19]. These findings suggest that although intraperitoneal chemotherapy may reduce recurrence, the rate remains high regardless of treatment strategy. Historically, infra-colic omentectomy was considered sufficient for complete cytoreduction. However, undetected microscopic implants in the retained omentum may have contributed to rapid progression postoperatively, mistakenly classified as recurrence. Such cases likely reflect disease progression rather than true recurrence, possibly leading to overestimation of recurrence rates in earlier studies. The objective of the present study is to evaluate the incidence and anatomical distribution of recurrence in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer treated with complete cytoreductive surgery in combination with HIPEC.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The medical records of 239 women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer who underwent complete Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) in combination with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) between January 1st 2003 and December 31st 2023 were retrieved from a prospectively maintained institutional database. Diagnosis was established by physical examination, hematological and biochemical testing, tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, CA-125), thoracic and abdominal imaging (CT or MRI), and cytology or biopsy (either percutaneous or laparoscopic).Eligible patients were those capable of undergoing major surgery, with an ECOG performance status <2, white blood cell count >4000/mL, platelet count >150000/mL, blood urea <50 mg/dL, serum creatinine <1.5 mg/dL, no recent history of pulmonary disease, no signs of cardiomyopathy or electrocardiographic abnormalities, and no active urinary tract infection. All patients were over 18 years of age. Exclusion criteria included history of another malignancy at risk for recurrence (except adequately treated basal cell carcinoma or in-situ cervical cancer), distant unresectable metastases, pregnancy, or high-risk comorbidities involving renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, or pulmonary systems.

Ethical Aspects

A signed consent form, including an authorization statement that medical records can be used for future research, was obtained preoperatively. For the current retrospective, observational study an approval of the Institutional Ethical Committee was not deemed necessary.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was recurrence sites. Secondary outcomes were DFS and OS.

Treatment Procedure

All patients underwent laparotomy via a midline incision extending from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis. The extent of prior surgery was assessed based on operative reports. Tumor volume was evaluated across the 13 abdominopelvic regions, and the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) was calculated [20]. Standard peritonectomy procedures [21] and multivisceral resections were performed to achieve complete cytoreduction. The Completeness of Cytoreduction (CC) score was documented postoperatively [20]. From the total of 239 patients, 192 (80.3%) received Hyperthermal Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Out of the remaining 47 patients, 40 of them were chosen - as part of a different study protocol- to receive CRS alone, while a small number (7 patients) did not consent to the use of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. HIPEC was administered using the open “Coliseum” technique, following macroscopic tumor resection and prior to gastrointestinal reconstruction. The skin edges were suspended using long sutures on a Thompson self-retaining retractor to allow infusion of 2-3 liters of prime solution. A HIPEC delivery system (Sun Chip, Gamida Tech, Paris, France) equipped with dual roller pumps, heat exchanger, reservoir, inflow/outflow tubing, and thermal probes was used. Once the mean intra-abdominal temperature reached 40°C, cytotoxic agents were instilled. HIPEC was performed at 42.5-43°C for 90 minutes with intraperitoneal cisplatin (50 mg/m²) and doxorubicin (15 mg/m²), along with intravenous ifosfamide (1300 mg/m²) and mesna (260 mg/m²). Mesna was repeated twice at 4-hour intervals. In cases of diaphragmatic breach or resection, bicavitary HIPEC (peritoneal and pleural) was performed. The diaphragmatic defects and the gastrointestinal tract were restored after the completion of HIPEC. All patients were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for a minimum of 24 hours. Postoperative complications were recorded and graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [22]. All surgical specimens underwent detailed histopathological examination. Data recorded included tumor type, differentiation grade, and the number and sites of resected and infiltrated lymph nodes. Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy with platinum-based agents and taxanes was administered. From 2019 onward, maintenance therapy with bevacizumab was introduced, and PARP inhibitors became available from 2022.

Follow-Up

All patients were followed-up every 3-4 months during the first year and every 6 months thereafter, with physical examination, hematological and biochemical testing, tumor markers (CEA, CA-125), and imaging studies (abdominal and thoracic CT or MRI). Since 2003, 4 out of the total 239 patients reached the full 20-year follow-up milestone. Recurrence and the exact anatomical sites of recurrence were carefully recorded. Initially, sites of recurrence were categorized as distant or locoregional. Metastatic lesions in the liver parenchyma, lungs, brain, bones, spleen, or lymph nodes were classified as distant metastases. Recurrence involving the peritoneal surfaces (below the diaphragm) or the vaginal vault was classified as locoregional. Disease-Free Survival (DFS) was defined as the interval between initial diagnosis and the first radiological evidence of recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval from initial diagnosis to death or last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All recorded clinical and pathological variables were analyzed for associations with recurrence. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression with backward elimination to identify independent prognostic factors for recurrence. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between groups were performed using the log-rank test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Analysis

Between January 1st 2003 and December 31st 2023, a total of 239 women (mean age 61.3 ± 12 years, range 16-100) underwent complete cytoreductive surgery (CC-0) for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (FIGO stage III). Of those, 192 patients (80.3%) received CRS combined with HIPEC.

Baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in (Table 1).

- The mean Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) was 8 ± 6 (range: 1-35).

- The mean number of Peritonectomy Procedures (PP) was 5 ± 3 (range: 1-13).

- Mean intraoperative blood loss was 203 ± 338 mL (range: 100-2500).

- Mean transfused Blood Units (BU) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were 1 ± 1 (range: 0-10) and 3 ± 3 (range: 0-12), respectively.

- Mean ICU stay was 1 ± 1 day (range: 1-8).

- The mean Number Of Suture Lines (NSL) and Anastomoses (NA) was 2 ± 1 (range: 0-10) and 1 ± 1 (range: 0-5), respectively.

The median follow-up duration was 22 months (range: 3-240). Recurrence was observed in 94 patients (39.3%), with 46 (19.2%) presenting with distant and 48 (20.1%) with locoregional recurrence (Table 1). As shown in (Table 2), PSS, HIPEC treatment, and intraoperative FFP transfusion were significantly associated with disease-specific survival (Table 2). Univariate analysis revealed that HIPEC, FFP transfusion, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT), and prior surgical history were associated with recurrence (Table 3). Multivariate analysis identified PSS, NACT, and FFP transfusion as independent predictors of recurrence.

|

Variable |

No. of patients |

% |

|

Recurrence |

94 |

39.3 |

|

Performance status |

||

|

- 1 |

208 |

87 |

|

- 2 |

31 |

13 |

|

ASA class |

||

|

- I |

194 |

81.2 |

|

- II |

42 |

17.6 |

|

- III |

3 |

1.3 |

|

Prior Surgery Score (PSS) |

||

|

- PSS-0 |

108 |

45.2 |

|

- PSS-1 |

31 |

13 |

|

- PSS-2 |

67 |

28 |

|

- PSS-3 |

33 |

13.8 |

|

Tumor volume |

||

|

- Large volume |

204 |

85.4 |

|

- Small volume |

35 |

14.6 |

|

Lymph node resection |

||

|

- Retroperitoneal |

85 |

35.6 |

|

- Conventional |

154 |

64.4 |

|

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) |

46 |

19.2 |

|

Peritoneal cancer index (PCI) |

||

|

- 0-13 |

188 |

78.7 |

|

- 14-20 |

40 |

16.7 |

|

- 21-39 |

11 |

4.6 |

|

Morbidity |

61 |

25.5 |

|

Age (years) |

||

|

- <65 |

134 |

56.1 |

|

- ≥65 |

105 |

43.9 |

|

HIPEC performed |

192 |

80.3 |

|

Type of cytoreductive surgery (CRS) |

||

|

- Primary |

108 |

45.2 |

|

- Interval |

46 |

19.2 |

|

- Secondary |

85 |

35.6 |

Table 1: Patient Characteristics and Clinical Variables (N: 239).

|

Variable |

Recurrence (%) |

2-year PFS (%) |

Disease Specific Survival Median (95% CI) |

p value |

|

Age |

||||

|

<65 years |

63 (43.2) |

59.2 |

30 (20.9-30.1) |

0.497 |

|

>65 years |

31 (33.3) |

72.2 |

40 (27.2-52.9) |

|

|

Performance status |

||||

|

1 |

86 (41.3) |

64.7 |

36 (26-46) |

0.143 |

|

2 |

8 (25.8) |

53.5 |

39 (12.9-65.1) |

|

|

ASA |

||||

|

I |

80 (41.1) |

64.7 |

36 (26.1-45.9) |

0.26 |

|

II |

14 (31.1) |

58.5 |

39 (18.3-59.7) |

|

|

PSS |

||||

|

PSS-0 |

28 (25.9) |

85.6 |

99 |

0.006 |

|

PSS-1 |

14 (45.2) |

63.7 |

26 (11.7-40.3) |

|

|

PSS-2 |

33 (49.3) |

54.8 |

29 (19.6-38.4) |

|

|

PSS-3 |

19 (57.6) |

51.5 |

26 (13.2-38.8) |

|

|

Tumor volume |

||||

|

Large |

84 (41.2) |

61.8 |

34 (24.8-43.2) |

0.274 |

|

Small |

10 (28.6) |

75.4 |

47 (26.2-67.8) |

|

|

PP |

||||

|

1-5 |

52 (36.4) |

65 |

40 (5.8-74.2) |

0.184 |

|

6-10 |

35 (43.8) |

62.5 |

30 (22-38) |

|

|

>10 |

7 (43.8) |

55.6 |

25 (0-54.2) |

|

|

LNR |

||||

|

Abdomino-pelvic |

32 (37.6) |

65.3 |

43 (18.7-67.3) |

0.786 |

|

Conventional |

62 (40.3) |

62.9 |

32 (23.4-40.6) |

|

|

PCI |

||||

|

0-13 |

73 (38.8) |

65 |

36 (29-43) |

0.443 |

|

14-20 |

17 (42.5) |

62.5 |

29 (0.4-57.6) |

|

|

21-39 |

4 (36.4) |

55.6 |

25 (0-52.9) |

|

|

NACT |

25 (54.3) |

55.3 |

28 (21.7-34.3) |

0.074 |

|

BL |

||||

|

<400ml |

80 (39.4) |

64.4 |

39 (26.9-51.1) |

0.275 |

|

401-800ml |

11 (40.7) |

50.2 |

28 (3.8-52.1) |

|

|

>801 |

3 (33.3) |

60 |

32 (18-46) |

|

|

BU |

||||

|

0 |

55 (39.3) |

65.1 |

44 (12.8-75.3) |

0.168 |

|

1-2 |

29 (40.8) |

66.9 |

28 (23.1-32.9) |

|

|

>2 |

10 (35.7) |

48.8 |

23 (0-53) |

|

|

FFP |

||||

|

0 |

29 (34.9) |

78.3 |

99 (43.4-154.6) |

<0.001 |

|

1-2 |

9 (56.3) |

69.6 |

29 (22.6-35.5) |

|

|

3-4 |

37 (37) |

60.2 |

33 (18.5-47.5) |

|

|

>4 |

19 (47.5) |

28.1 |

15 (10.6-19.4) |

|

|

NSL |

||||

|

0-1 |

92 (39.3) |

63.9 |

36 (25.9-46.1) |

0.234 |

|

>2 |

2 (40) |

50 |

8 |

|

|

NA |

= |

|||

|

0-2 |

94 (39.7) |

63.7 |

- |

- |

|

>2 |

0 (0) |

- |

- |

|

|

DS |

||||

|

<300 min |

9 (28.1) |

85.4 |

99 |

0.096 |

|

301-480 min |

79 (39.9) |

59.5 |

30 (20.7-39.3) |

|

|

>481 min |

6 (66.7) |

57.1 |

32 (14-50) |

|

|

HIPEC |

79 (41.1) |

60.3 |

32 (25.3-38.7) |

0.027 |

Explanations: PCI: Peritoneal Cancer Index, PP: Peritonectomy Procedures, BL: Blood Loss, BU: Transfused Blood Units, FFP: Number of Transfused Fresh Frozen Units, NSL: Number of Suture Lines, NA: Number of Anastomoses, DS: Duration of Surgery

Table 2: Recurrence, Progression-Free Survival and Disease-Specific Survival.

|

Variable |

P value (Univariate) |

cHR (95% CI) |

P value (Multivariate) |

aHR (95% CI) |

|

Age |

||||

|

<65 |

REF. |

- |

||

|

>65 |

0.503 |

0.86 (0.56-1.83) |

- |

|

|

Performance status |

||||

|

1 |

REF. |

|||

|

2 |

0.153 |

1.7 (0.82-3.54) |

NS |

|

|

ASA class |

||||

|

I |

REF. |

- |

||

|

II |

0.268 |

1.38 (0.78-2.44) |

- |

|

|

PSS |

||||

|

PSS-0 |

REF. |

REF. |

||

|

PSS-1 |

0.044 |

1.93 (1.03-3.68) |

0.173 |

1.59 (0.83-3.09) |

|

PSS-2 |

0.016 |

1.86 (1.12-3.08) |

0.001 |

2.37 (1.41-3.97) |

|

PSS-3 |

0.002 |

2.56 (1.43-4.59) |

0.001 |

2.64 (1.46-4.76) |

|

Tumor volume |

||||

|

Large |

REF. |

- |

||

|

Small |

0.282 |

0.7 (0.6-1.35) |

- |

|

|

PP |

||||

|

1-5 |

REF. |

|||

|

6-10 |

0.153 |

1.37 (0.89-2.11) |

NS |

|

|

>10 |

0.166 |

1.75 (0.79-3.85) |

||

|

LNR |

||||

|

Abdomino-pelvic |

REF. |

- |

||

|

Conventional |

0.789 |

1.06 (0.69-1.63) |

- |

|

|

HIPEC |

||||

|

Yes |

REF. |

|||

|

No |

0.032 |

0.54 (0.31-0.95) |

NS |

|

|

PCI |

||||

|

0-13 |

REF. |

- |

||

|

14-20 |

0.453 |

1.22 (0.72-2.08) |

- |

|

|

21-39 |

0.284 |

1.74 (0.63-4.76) |

- |

|

|

NACT |

||||

|

No |

REF. |

REF. |

||

|

Yes |

0.079 |

1.51 (0.95-2.39) |

0.01 |

1.93 (1.17-3.2) |

|

BL |

||||

|

<400 ml |

REF. |

- |

||

|

401-800 ml |

0.137 |

1.66 (0.88-3.12) |

- |

|

|

>800 ml |

0.939 |

1.05 (0.33-3.32) |

- |

|

|

BU |

||||

|

0 |

REF. |

- |

||

|

1-2 |

0.066 |

1.53 (0.97-2.41) |

- |

|

|

>2 |

0.498 |

1.26 (0.64-2.48) |

- |

|

|

FFP |

||||

|

0 |

REF. |

REF. |

||

|

1-2 |

0.055 |

2.09 (0.99-4.43) |

0.067 |

2.11 (0.95-4.67) |

|

3-4 |

0.11 |

1.49 (0.91-2.43) |

0.017 |

1.86 (1.12-3.11) |

|

>4 |

<0.001 |

3.23 (1.8-5.77) |

<0.001 |

4.31 (2.34-7.94) |

|

NSL |

||||

|

1 |

REF. |

- |

||

|

2 |

0.252 |

2.27 (0.56-9.26) |

- |

|

|

DS |

||||

|

<300 min |

REF. |

- |

||

|

301-480 min |

0.065 |

1.92 (0.96-3.83) |

- |

|

|

>480 min |

0.057 |

2.74 (0.97-7.72) |

- |

Explanations: PCI: Peritoneal Cancer Index, PP: Peritonectomy Procedures, BL: Blood Loss, BU: Transfused Blood Units, FFP: Number of Transfused Fresh Frozen Units, NSL: Number of Suture Lines, NA: Number of Anastomoses, DS: Duration of Surgery

Table 3: Analysis of Recurrence.

Recurrence rates by type of CRS were

- Primary CRS: 59 of 131 (45%)

- Interval CRS: 16 of 25 (64%)

- Secondary CRS: 19 of 24 (79.2%) (p< 0.001)

- The most frequent anatomical site of recurrence was the lymph nodes, followed by the small bowel, liver, and pelvis (Table 4).

- Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed:

- 1-, 5-, and 10-year DFS: 82.9% ± 2.8%, 39.6% ± 4.4%, and 30.9% ± 5.2%, respectively (Figure 1).

- Mean DFS: 95.7 ± 9.8 months (95% CI: 6.51-114.85)

- Median DFS: 36 ± 4 months (95% CI: 28.14-43.86)

The 5-, 10-, and 20-year OS among patients treated with CC-0 CRS and HIPEC was 78%, 70%, and 70%, respectively (Figure 2). In univariate analysis, performance status, ASA class, extent of peritoneal disease, FFP transfusion, and duration of surgery were significantly associated with overall survival (p< 0.05). Multivariate analysis confirmed performance status as an independent prognostic factor for OS (Table 5). In patients with lymph node recurrence, the 5-year OS was 38%, with a median survival of 29 months. For patients with locoregional recurrence, the 5-year OS was 64%, and the median survival was not reached.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

|

Location |

No. of patients |

% |

|

Lymph nodes |

39 |

41.1 |

|

Anterior peritoneum |

3 |

3.2 |

|

Pelvis |

9 |

9.5 |

|

Small bowel |

19 |

20 |

|

Left ureter |

2 |

2.1 |

|

Vaginal vault |

3 |

3.2 |

|

Liver |

11 |

11.6 |

|

Left hemidiaphragm |

2 |

2.1 |

|

Omental bursa |

2 |

2.1 |

|

Right hemidiaphragm |

4 |

4.2 |

|

Lung |

1 |

1.1 |

Table 4: Location Of Recurrent Disease.

|

Variable |

P value (Univariate) |

HR |

P value (Multivariate) |

95% CI |

|

PS |

<0.001 |

13.711 |

<0.001 |

2.112-11.344 |

|

ASA |

0.004 |

|||

|

PSS |

0.223 |

|||

|

TV |

0.154 |

|||

|

LNR |

0.557 |

|||

|

HIPEC |

0.189 |

|||

|

Stoma |

0.002 |

8.874 |

0.003 |

0.046-0.53 |

|

NACT |

0.804 |

|||

|

PCI |

0.032 |

|||

|

BL |

0.356 |

|||

|

BU |

0.122 |

|||

|

FFP |

0.001 |

|||

|

Morbidity |

0.186 |

|||

|

NSL |

0.639 |

|||

|

Age |

0.665 |

|||

|

DS |

0.047 |

Explanations: PS: Performance Status, ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists, PSS: Prior Surgery Score, TV: Tumor Volume, LNR: Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Resection, NACT: Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy, PCI: Peritoneal Cancer Index, BL: Blood Loss, BU: Transfused Blood Units, FFP: Number of Transfused Fresh Frozen Units, NSL: Number of Suture Lines, DS: Duration Of Surgery.

Table 5: Analysis of Overall Survival.

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier Curve For Disease-Free Survival.

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier Curve For Overall Survival.

Discussion

Historically, the standard surgical approach for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer included infracolic omentectomy and, only rarely, selective resection of macroscopically seeded peritoneal surfaces. Although the pathophysiology of peritoneal carcinomatosis is now well understood, and the introduction of standard peritonectomy procedures has transformed the surgical management of peritoneal disease [21], many surgeons continue to adhere to outdated operative strategies. Importantly, complete cytoreduction cannot be reliably achieved with infracolic omentectomy alone. In such cases, the detection of new disease postoperatively should more appropriately be considered progression rather than true recurrence. The term "recurrence" is most accurately applied in those cases in which standard peritonectomy procedures have been performed, and the surgeon may reliably confirm that complete macroscopic cytoreduction (CC-0) has been achieved. Therefore, we assumed that the precise estimation of the recurrence rate would be reliable if only patients undergoing complete cytoreduction (CC-0 surgery) are included. Despite optimal surgical resection and adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, recurrence remains a frequent event, with reported rates ranging from 62% to 88% [23-25]. As demonstrated in our findings, the recurrence rate differs significantly among primary, interval, and secondary cytoreductive procedures, highlighting the importance of patient selection and timing of intervention [16]. Several prospective studies have demonstrated improved overall and progression-free survival in patients treated with complete CRS followed by normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy [26-30]. The addition of HIPEC has been associated with a reduction in recurrence rates, likely due to its capacity to eradicate residual microscopic disease that would otherwise escape detection [17,18].

One major advantage of intraperitoneal chemotherapy lies in its pharmacologic profile, which enables high local drug concentration with minimal systemic exposure [31]. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that intraperitoneal administration also delivers therapeutic drug levels to the portal circulation, potentially targeting hepatic and lymphatic micrometastases. This is supported by data showing that approximately 90% of intraperitoneally administered agents are absorbed via the visceral peritoneum [32]. In our study, we observed a 10- and 20-year overall survival rate of 70%, which is notably higher than typically reported. This may be attributed to the fact that no recurrence was observed beyond the 10-year follow-up period, suggesting that long-term disease control or cure is achievable in a selected subgroup of patients who undergo complete CRS and HIPEC. Previous studies have shown that the majority of recurrence in epithelial ovarian cancer is locoregional, predominantly involving the abdominal cavity [17,18,33]. Peritoneal recurrence commonly occurs both at previously treated and untreated sites following CRS [33]. Notably, the initial recurrence frequently involves the upper abdomen [34]. This pattern supports the concept of tumor cell entrapment, whereby residual microscopic disease persists despite apparent complete cytoreduction [35,36]. According to this theory, traumatized peritoneal surfaces attract free cancer cells that become entrapped in fibrin clots or blood deposits and later proliferate into macroscopic implants under the influence of growth factors [37]. Interestingly, in our study, distant and locoregional recurrence was equally distributed among cases, diverging from traditional patterns. One possible explanation is our classification of lymph node involvement as distant metastasis, a categorization that remains inconsistently defined in the literature, though it does not contradict previously published findings [18]. A second explanation may lie in the broad application of HIPEC in our cohort, which appears to contribute to more effective locoregional disease control.

This hypothesis aligns with results from Chambers et al., who reported that 50% of ovarian cancer patients treated with CRS and HIPEC experienced extraperitoneal first recurrence [18]. Similar trends have been observed in patients receiving Intravenous/Intraperitoneal (IV/IP) chemotherapy [17,30]. These findings suggest that HIPEC offers comparable efficacy to IV/IP chemotherapy in controlling locoregional disease, while possibly increasing the risk for extraperitoneal relapse [17,30,38]. Patients whose recurrence is primarily lymphatic tend to have better survival outcomes than those with peritoneal or hematogenous metastases [25]. However, our data diverge from this trend, showing a 5-year survival rate of 64% for patients with locoregional recurrence, compared to only 38% in those with lymph node involvement. Amate et al. reported nodal recurrence in 38% of cases, with 87% of those occurring below the diaphragm and 13% above. The main risk factors for nodal recurrence included preoperative nodal involvement and diffuse peritoneal spread [33]. In our cohort, 41.1% of patients developed nodal recurrence. These findings are consistent with previous studies: Esselen et al. and Tanner et al. reported 41% and 45% respectively of extraperitoneal recurrence in patients treated with IP chemotherapy [17,30]. Conversely, Usami et al. demonstrated that 60% of recurrence sites following CRS were confined to the peritoneal cavity [39]. Nevertheless, complete cytoreduction remains the most effective measure to improve outcomes by reducing recurrence risk [40].

Despite aggressive CRS and the adjunctive use of HIPEC, the recurrence rate in our CC-0 cohort remains 39.3%. A plausible contributing factor may be the residual microscopic disease along the mesenteric border of the small intestine, where complete electro-evaporation of tumor nodules is technically challenging. This limitation is particularly evident in recurrent disease, even after meticulous adhesiolysis. Furthermore, tumor emboli trapped within scar tissue may resist eradication by intraperitoneal chemotherapy, unlike freely circulating tumor cells. Patients experiencing early recurrence often have biologically aggressive tumors [41]. Increased risk of recurrence has been associated with lymph node involvement, selective peritonectomy, and incomplete cytoreduction, even when residual disease is less than 0.25 cm [42]. While both peritoneal carcinomatosis extent and nodal infiltration significantly impact progression-free survival, they appear to exert less influence on overall survival [42]. Ultimately, recurrence is determined more by what the surgeon leaves behind than by what is removed [43]. This study has some limitations. Its retrospective nature may introduce selection or reporting biases. Moreover, although high-volume, the study is conducted in a single center, somewhat affecting its reliability. Finally the classification of nodal involvement as distant metastasis remains somewhat arbitrary, as the distinction between intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal lymphatic spread is not clearly defined. In our analysis, we did not differentiate between abdominal and extra-abdominal nodal recurrence. The strengths of our study include the use of strict criteria to define Complete Cytoreduction (CC-0) and the inclusion of a relatively large patient population undergoing uniform treatment protocols in a high-volume center.

Conclusions

Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer is increasingly trending towards treatment of peritoneal disease, with significant impact on recurrence rate. Complete cytoreduction (CC-0) rises as a major factor affecting recurrence and the addition of HIPEC has been associated with increased disease-free survival rates. Our study focuses mainly on recurrence sites following complete CRS and HIPEC, with the interesting finding of equal distribution between distant and locoregional recurrence. These results may be affected by the categorization of lymph node involvement as distant disease, as well as by the broad application of HIPEC, which seems to offer better locoregional control. Interestingly enough, the 5-year survival rates for patients with locoregional recurrence was 64% compared to the respective 38% of the lymph node involvement sub-group, a finding which contradicts bibliographical data. Despite its limitations, our study contributes to the investigation on recurrence rates and sites of women undergoing treatment for epithelial ovarian cancer, with an emphasis on clearly defined complete cytoreduction criteria and the use of HIPEC in a uniformly applied perioperative protocol in a high-volume center.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, C.M. and A.A.T.; methodology, C.M. and A.A.T.; validation, M.D. and E.E.; formal analysis, C.M. and D.K.; investigation, C.M.; data curation, A.A.T and A.K..; writing—original draft preparation, C.M. and A.A.T.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and E.E.; visualization, C.M. and G.T.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, M.D. and E.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethical Considerations: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional approval was obtained. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement: The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Randall TC, & Rubin SC (2001) Cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America 81: 871-83.

- Cannistra SA (2004) Cancer of the ovary. The New England Journal of Medicine 351: 2519-2529.

- Jemals A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, et al. (2009) Cancer statistics, 2009. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 59: 225-249.

- Horner W, Peng K, Pleasant V, Brackmann M, Ebott J, et al. (2019) Trends in surgical complexity and treatment modalities utilized in the management of ovarian cancer in an era of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecologic Oncology 154: 283-289.

- Nikolaidi A, Fountzilas E, Fostira F, Psyrri A, Gogas H et al. (2022) Neoadjuvant treatment in ovarian cancer: New perspectives, new challenges. Frontiers in Oncology 12: 820128.

- van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, van Leeuwen JH, Schreuder H, et al. (2018) Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 378: 230-240.

- Lee YJ, Lee JY, & Cho MS (2019) Incorporation of paclitaxel-based hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery: A protocol-based pilot study. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 30: e3.

- Charo LM, Jou J, & Binder P (2020) Current status of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for ovarian cancer in the United States. Gynecologic Oncology 159: 681-686.

- Di Giorgio A, Naticchioni E, Biacchi D, Sibio S, Accarpio F, et al. (2008) Cytoreductive surgery (peritonectomy procedures) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the treatment of diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Cancer 113: 315-325.

- Raspagliesi F, Kusamura S, Campos Torres JC, de Souza G, Ditto A, et al. (2006) Cytoreduction combined with intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion chemotherapy in advanced/recurrent ovarian cancer patients: The experience of National Cancer Institute of Milan. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 32: 671-675.

- Cotte E, Glehen O, Mohamed F, Lamy F, Falandry C, et al. (2007) Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia for chemo-resistant and recurrent advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. World Journal of Surgery 31: 1813-1820.

- Gonzalez Bayon L, Steiner MA, Vasquez-Jimenez W, Asencio JM, Alvarez de Sierra P, et al. (2013) Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma: Upfront therapy, at first recurrence, or later? European Journal of Surgical Oncology 39: 1109-1115.

- Kim SI, & Kim JW (2021). Role of surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. ESMO Open 6: 100149.

- Hoskins WJ, Bundy BN, Thigpen JT, & Omura GA (1992) The influence of cytoreductive surgery on recurrence-free interval and survival in small-volume stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic Oncology 47: 159-166.

- Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, & Montz FJ (2002) Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: A meta-analysis. Journal of ClinicalOncology 20: 1248-1259.

- Gadducci A, Cosio S, Zizioli V, Notaro S, Tana R, et al. (2017) Complete response after primary debulking surgery plus chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking surgery: An Italian multicenter retrospective study. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 27: 28-36.

- Esselen KM, Rodriguez N, Growdon W, Krasner C, Horowitz NS, et al. (2012) Patterns of recurrence in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers treated with intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Gynecologic Oncology 127: 51-54.

- Chambers LM, Yao M, Morton M, Gruner M, Chichura A, et al. (2021) Patterns of women with advanced and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. GynecologicOncology 161: 389-395.

- Muñoz-Casares FC, Medina-Fernández FJ, Arjona-Sánchez A, Casado-Adam Á, Sánchez-Hidalgo JM, et al. (2016) Peritonectomy procedures and HIPEC in the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer: Long-term outcomes and perspectives from a high-volume center. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 42: 224-233.

- Jacquet P, & Sugarbaker PH (1996) Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. In P. H. Sugarbaker (Ed.), Cancer Treatment and Research 359-374.

- Sugarbaker PH (1995) Peritonectomy procedures. Annals of Surgery 221: 29-42.

- Dindo D, Demartines N, &Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Annals of Surgery 240: 205-213

- Burg L, Timmermans M, van der Aa M, Boll D, Rovers K, et al. (2020) Incidence and predictors of peritoneal metastases of gynecological origin: A population-based study in the Netherlands. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 31: e58.

- Gardner AB, Charo LM, Mann AK, Kapp DS, Eskander RN, et al. (2020) Ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancer patients with distant metastases at diagnosis: Most common location and outcomes. Clinical&ExperimentalMetastasis 37: 107-113.

- Roze JF, Veldhuis WB, Hoogendam JP, Verheijen RHM, Scholten RJPM, et al. (2020) Prognostic value of radiological recurrence patterns in ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 157: 606-612.

- Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, O'Toole R, Williams SD, et al. (1996). Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. The NewEngland Journal of Medicine 335: 1950-1955.

- Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson DL,et al. (2001) Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Phase III trial of standard dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: An intergroup study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 19: 1001-1007.

- Armstrong DK, Bundy BN, Wenzel L, Huang HQ, Baergen R, et al. (2006) Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 354: 34-43.

- Tewari D, Java JJ, Salani R, Armstrong DK, Markman M, et al. (2015) Long-term survival advantage and prognostic factors associated with intraperitoneal chemotherapy treatment in advanced ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33: 1460-1466.

- Tanner EJ, Black DR, Zivanovic O, Kehoe SM, Dao F, et al. (2012) Patterns of first recurrence following adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for stage IIIC ovarian cancer. GynecologicOncology 124: 59-62.

- Dedrick RL (1985) Theoretical and experimental basis of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Seminars in Oncology 12: 1-6.

- Speyer JL, Sugarbaker PH, Collins JM, Dedrick RL, Klecker RWJR, et al. (1981) Portal levels and hepatic clearance of 5-fluorouracil after intraperitoneal administration in humans. Cancer Research 41: 1916-1922.

- Amate P, Huchon C, Dessapt AL, Bensaid C, Medioni J, et al. (2013) Ovarian cancer: Sites of recurrence. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 23: 1590-1596.

- Hamilton CA, Miller A, Miller C, Krivak TC, Farley JH, et al. (2011) The impact of disease distribution on survival in patients with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer cytoreduced to microscopic residual: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic Oncology 122: 521-526.

- Sugarbaker PH (2007) Peritoneum as the first line of defense in carcinomatosis. Journal of Surgical Oncology 95: 93-96.

- Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, & Fares Y (2020) Molecular principles of metastasis: A hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 5: 28.

- Lemoine L, Sugarbaker PH, & Van der Speeten K (2016) Pathophysiology of colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: Role of the peritoneum. World Journal of Gastroenterology 22: 7692-7707.

- Ceresoli M, Verrengia A, Montori G, Busci L, Coccolini F, et al. (2018) Effect of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy on relapse pattern in primary epithelial ovarian cancer: A propensity score based case-control study. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 29 (e53).

- Usami T, Kato K, Taniguchi T, Abe A, Nomura H, et al. (2014) Recurrence patterns of advanced ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers after complete cytoreduction during interval debulking surgery. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer 24: 991-996.

- Paik ES, Lee YY, Shim M, Choi HJ, Kim TJ, et al. (2016) Timing and patterns of recurrence in epithelial ovarian cancer patients with no gross residual disease after primary debulking surgery. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 56: 639-647.

- Bijelic L, Yan TD, & Sugarbaker PH (2007) Failure analysis of recurrent disease following complete cytoreduction and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology 14: 2281-2288.

- Sinukumar S, Damodaran D, Mukurdipi R, Mehta S, Paul L, et al. (2021) Patterns of recurrence after interval cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC following neoadjuvant chemotherapy in primary advanced stage IIIC/IVA epithelial ovarian cancer. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 47: 1427-1433.

- Esquivel J, Farinetti A, & Sugarbaker PH (1999) Elective surgery in recurrent colon cancer with peritoneal seeding: When to and when not to proceed. Giornaledi Chirurgia 20: 81-86.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.