Single-Center Comprehensive Investigation of Perioperative Outcomes Following Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass and Mini-Gastric Bypass Utilizing Ethicon PDS-TM-II Suture

by Christine Stroh1*, Martin Hukauf2,Daniela Adolf2, Omar Thaher3

1Department of Obesity and Metabolic Surgery, Municipal Hospital, Straße des Friedens 122, 07548 Gera, Germany

2StatConsult Society for Clinical and Health Services Research GmbH, Am Fuchsberg 11, 39112 Magdeburg, Germany

3Department of Surgery, Marien Hospital Herne, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Hölkeskampring 40, 44625 Herne, Germany

*Corresponding author: Christine Stroh, Department of Obesity and Metabolic Surgery, Municipal Hospital, Straße des Friedens 122, 07548 Gera, Germany

Received Date: 29 March 2025

Accepted Date: 03 April 2025

Published Date: 07 April 2025

Citation: Stroh C, Hukauf M, Adolf D, Thaher O (2025) Single-Center Comprehensive Investigation of Perioperative Outcomes Following Laparoscopic Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass and Mini-Gastric Bypass Utilizing Ethicon PDS-TM-II Suture. J Surg 10: 11292 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011292

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) and Laparoscopic Mini-Gastric Bypass (LMGB) are prevalent techniques in Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery (BMS). Both treatments have demonstrated efficacy in the short and long term; nonetheless, they are accompanied by particularly technical perioperative challenges and risks, some of which may require revision.

Methods: This study analyzed data from a single center about the use of PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture Set as tension-retaining and anchoring sutures for anastomoses in Primary (P) and Secondary (R) LRYGB and LMGB surgeries following Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG). The short-term outcome (within 30 postoperative days and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months) were analyzed to evaluate the obstacles related to this surgical approach.

Results: 189 individuals completed LRYGB and LMGB, including 59 P-LRYGB, 16 P-LMGB, 67 R-LRYGB and 47 R-LMGB after SG. The mean age was 48.5 (±10.7) years, and the mean Body Mass Index (BMI) was 41.5 (±6.5) kg/m2. The prevalence of comorbidities was 77.8%. The total intraoperative and postoperative complication rate was 8.5%, each, whereas the specific postoperative complication rate was 2.6%, with no documented 30-day mortality. Two patients need reoperation; one due to hemorrhage and the other due to peritonitis caused by small bowel leakage at the suture.

Conclusions: The PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture Set is both safe and feasible for anastomosis in laparoscopic and robotic surgery, as demonstrated by the findings of our investigation. Complications associated with the type of suture were not observed to be more prevalent than those described in the literature.

Keywords: Bariatric Surgery; Peroperative Complication; RouxEn-Y Gastric Bypass; Surgical Anastomoses

Introduction

A statistical analysis from 2021 indicates that 52.7% of adults in Germany are overweight. Compared with other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, Germany ranks 21st in the proportion of overweight adults [1,2]. The development of bariatric and metabolic surgery (BMS) has experienced incredible growth in recent years, both nationally and internationally, following its recognition as a treatment modality for obesity and related diseases [3,4]. Furthermore, advancements in minimally invasive surgery have been consistently pursued. Even more innovative is robotic-assisted surgery, which has gained acceptance in many surgical specialties, and is increasingly used in BMS [5-7]. This development has improved patient outcomes after BMS in terms of postoperative recovery and lower hospital costs [8]. However, some surgical procedures have gained more acceptance than others because they provide better long-term results [9-11]. In addition, the expected goal of surgery, which varies from patient to patient, influences the choice of operation method [12,13]. Factors that could affect the decision of surgery are the patient’s general health, current weight, surgeon’s experience, and medical history [14]. The development of laparoscopic and robotic approaches leads to several changes in operation techniques with using several kinds of sutures or staplers. These several devices also may be influencing the perioperative and short-term outcome [15,16]. Gastrointestinal anastomosis constitutes a vital phase in numerous laparoscopic and robotic bariatric surgical interventions. Depending on the experience of the surgeons and the equipment of the hospital, these anastomoses are usually performed using a handsewn, linear or circular stapling device or a combination of several procedures. Laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing is regarded as one of the most laborious and time-intensive components of this surgical procedure [17-19]. The aim of the following study is to analyze the outcome within utilizing the suture technique PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture Set (Ethicon, Raritan, NJ, USA). To evaluate this data, we performed a single-center study from 01.01.2020 until 31.05.2024 using the Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture in patients with Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) and Laparoscopic Mini-Gastric Bypass (LMGB) as a primary as well as a revisional procedure following Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG).

Material and Methods

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

Data were prospectively collected from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2024, and subsequently analyzed retrospectively. The investigation included primary (P) LRYGB and LMGB, as well as Secondary (R) LRYGB and LMGB subsequent to Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), utilizing the Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture. All participants completed a one-year follow-up period and were at least 18 years old. Only individuals possessing complete data were included in the study. The postoperative data were collected within 30 days postoperatively and at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All analyses were conducted in an exploratory manner. Thus, the full level of significance of 5% was deliberately used. The results tables display the mean value and standard deviation (STD) for (quasi-) continuous variable distributions, or also for log-transformed data in case of non-normal distribution, the mean value and simple range of dispersion after back-transformation. Contingency tables display the Absolute (N) and Relative (%) frequencies for categorical variables. Univariate analyses – unadjusted for confounders - for the surgical techniques were conducted: the chisquare test and an ANOVA for categorical and continuous outcome variables, respectively.

Surgical Technique

P-LRYGB and R-LRYGB

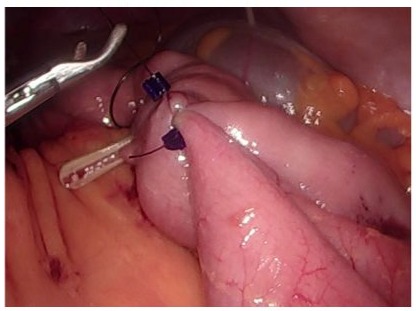

Following the typical setting of the patient, the surgical area is disinfected and draped, and a team time-out is conducted. Incision of the skin on the left paramedian approximately 15 cm inferior to the xiphoid process and insertion of the camera trocar. Establishment of a pneumoperitoneum at a pressure of 15 mm Hg. Diagnostic laparoscopy. A 5 mm trocar is now introduced into the epigastric angle, a 12 mm trocar into the left upper quadrant, and a 12 mm trocar into the right upper quadrant. The transverse colon is then relocated to the upper quadrant, with the duodenojejunal flexure observed adjacent to the inferior mesenteric vein. Measurement of a 60-centimeter biliary loop. A Dexon clip is utilized for marking and is secured to the anticipated gastric remnant with an anchoring and secure suture using a PDSTM Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture (Figure 1). Proceed to the lesser omentum at the level of the second vascular arcade. Transect the stomach utilizing a gold endoscopic linear stapler. Construct the gastric pouch precisely utilizing a 24 Fr. calibration tube and incorporating two supplementary blue endoscopic linear staplers (in primary RYGB but not in SG to RYGB). Mobilization of the stomach pouch and its incision over the positioned calibration tube. Incision of the small bowel loop, release of the securing suture. Anastomosis of the stomach to the small intestine across a distance of 50 mm utilizing a blue endoscopic linear stapler. Ongoing closure of the anterior wall Running closure of the anterior wall with barbed suture technique. Reinsertion of the calibration tube and conducting a leak test with methylene blue. No evidence of extravasation is present.

Preparation of the anticipated transection site of the biliary loop is now underway. Measurement of an intestinal loop measuring 150 cm in length. This is secured at the position of the attached Dexon clip. Creation of the alimentary and biliary loops around 6 cm distal to the securing suture, followed by anastomosis using a laterolateral suture technique. Closure of the entrance aperture via a continuous barbed suture. Closure of the Peterson space via a continuous Mersilene suture. Proceed to sever the biliary loop at the site of the affixed Dexon clip, which has been previously excised. The blind loop is further sutured to the pouch using a PDSTM II EthiEndo-Clip Suture (Figure 1). Another comprehensive examination revealed no hemorrhaging or foreign objects.

Figure 1: Illustration of the intraoperative application of the PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture.

P-LMGB and R-LMGB

In accordance with standard protocol, the patient is positioned in a 30° reverse Trendelenburg position, the surgical site is cleansed and wrapped, and a team time-out is performed. Incision of the skin on the left paramedian approximately 15 cm inferior to the xiphoid process, followed by the insertion of the camera trocar. Creation of a pneumoperitoneum at a pressure of 15 mm Hg. Diagnostic laparoscopy. A 5 mm trocar is put into the epigastric angle, a 12 mm trocar is placed in the left upper quadrant, and a 12 mm trocar is positioned in the right upper quadrant. The transverse colon is then relocated to the upper quadrant, with the duodenojejunal flexure observed adjacent to the inferior mesenteric vein. Measurement of a 150-centimeter biliary loop. An anchoring suture using PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture is performed to secure the small bowel to the anticipated gastric remnant. Incise the stomach utilizing a gold endoscopic linear stapler. Construct the gastric pouch precisely utilizing a 24 Fr. calibration tube and incorporating three supplementary blue endoscopic linear staplers. Mobilization of the stomach pouch and its incision over the positioned calibration tube. Incision of the small bowel loop, release of the securing suture. Anastomosis of the stomach to the small intestine across a distance of 50 mm utilizing a blue endoscopic linear stapler. Ongoing closure of the anterior wall via Running closure of anterior wall with a barbed suture. Reinsertion of the calibration tube and conducting a leak test with methylene blue. No evidence of extravasation is present. Another comprehensive examination revealed no hemorrhaging or foreign objects.

Results

189 patients were incorporated into the analysis. The PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture was utilized in all patients for anastomoses, purse-string sutures, and cape repair sutures. Table 1 illustrates the distribution of surgical procedures utilizing the Ethi-Endo-Clip.

|

Surgical procedure |

N |

% |

|

P-LRYGB |

59 |

31.2 |

|

P-LMGB |

16 |

8.5 |

|

R- LRYGB |

67 |

35.4 |

|

R- LMGB |

47 |

24.9 |

|

Total |

189 |

100 |

Table 1: Distribution of surgical procedures utilizing Ethi-EndoClip.

The gender distribution revealed a markedly higher proportion of females (77.2%) compared to males (22.8%), which was not significantly different between procedures (p = 0.076). The average age of patients was 45.5 (± 10.4) years for P-LRYGB, 51.5 (± 7.0) years for P-LMGB, 49.1 (± 11.8) years for R-LRYGB, and 50.4 (± 10.0) years for R-LMGB (p = 0.053). Patients with P-LMGB and R-LMGB exhibited a markedly elevated BMI compared to those with P-LRYGB and R-LRYGB (p<0.001). Table 2 presents the distribution of sex, BMI, and age specific to the surgical procedure.

|

Surgical procedure |

Age |

BMI |

Gender |

|||||

|

male |

female |

|||||||

|

N |

Mean/SD (Y) |

N |

Mean/SD (Kg/m2) |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

P-LRYGB |

59 |

45.5 ± 10.4 |

59 |

42.3 ± 5.4 |

10 |

16.9 |

49 |

83.1 |

|

P-LMGB |

16 |

51.5 ± 7.0 |

16 |

44.4 ± 5.1 |

4 |

25 |

12 |

75 |

|

R- LRYGB |

67 |

49.1 ± 11.8 |

67 |

38.2 ± 5.5 |

12 |

17.9 |

55 |

82.1 |

|

R- LMGB |

47 |

50.4 ± 10.0 |

47 |

44.4 ± 7.5 |

17 |

36.2 |

30 |

63.8 |

|

p-value |

0.053 |

<0.001 |

0.076 |

|||||

Table 2: Distribution of gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), and age in relation to surgical technique.

Regarding the ASA classification, 49.2% of patients were categorized as ASA II, while 50.3% were classified as ASA III. A substantially greater proportion of patients classified as ASA III underwent P-LMGB compared to those who received P-LRYGB (93.8% vs. 39.0%). The conversion from LSG to LMGB (R-LMGB) occurred more frequently in patients classified as ASA III compared to R-LRYGB (59.6% vs. 43.3%) (Table 3). There were only 12.2% of patients who did not have any comorbidities (Table 3). Overall, the prevalence of T2DM was 21.2%. A P-LMGB was performed in 81.3% of patients with T2DM. This is considerably higher than the percentage of patients with P-LRYGB (13.6%). T2DM was also more frequently observed in patients who underwent R-LMGB than in those who underwent R-LRYGB (11.9% vs. 23.4%). Hypertension affected 69.3% of all patients, while OSAS affected 23.3%. GERD was more prevalent in patients with P-LRYGB than in those with P-LMGB (50.8% vs. 6.3%). Additionally, patients who underwent R-LRYGB experienced a greater degree of GERD than those who underwent R-LMGB (38.8% vs. 8.5%). The aggregate prevalence of nicotine abuse was 2.6%.

|

Procedure |

p-value* |

||||||||

|

P-LRYGB |

P-LMGB |

R-LRYGB |

R-LMGB |

||||||

|

ASA-Classification and Comorbidities |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

ASA |

|||||||||

|

ASA II |

36 |

61 |

1 |

6.3 |

38 |

56.7 |

18 |

38.3 |

0.001 |

|

ASA III |

23 |

39 |

15 |

93.8 |

29 |

43.3 |

28 |

59.6 |

|

|

ASA IV |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2.1 |

|

|

Comorbidities |

|||||||||

|

No comorbidities |

6 |

10.2 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

14.9 |

7 |

14.9 |

0.356 |

|

T2DM (total) |

8 |

13.6 |

13 |

81.3 |

8 |

11.9 |

11 |

23.4 |

<0.001 |

|

IDDM |

7 |

11.9 |

11 |

68.8 |

5 |

7.5 |

2 |

4.3 |

<0.001 |

|

NIDDM |

1 |

1.7 |

2 |

12.5 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

17 |

0.006 |

|

Diet |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

1 |

2.1 |

0.697 |

|

Hypertension |

36 |

61 |

16 |

100 |

42 |

62.7 |

37 |

78.7 |

0.006 |

|

Cardial disease |

6 |

10.2 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

13.4 |

8 |

17 |

0.311 |

|

Pulmonal disease |

11 |

18.6 |

3 |

18.8 |

7 |

10.4 |

10 |

21.3 |

0.419 |

|

OSAS |

14 |

23.7 |

8 |

50 |

8 |

11.9 |

14 |

29.8 |

0.006 |

|

GERD |

30 |

50.8 |

1 |

6.3 |

26 |

38.8 |

4 |

8.5 |

<0.001 |

(T2DM = Diabetes Mellitus Type II, IDDM = Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus, NIDDM = Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus, OSAS = Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, GERD = Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease)

Table 3: ASA classification and the incidence of comorbidities.

Operation Time and Complications, Hospitalization and Postoperative Stay

There was a significant difference in average operation time (p<0.001), which was by far the shortest for R-LMGB (54.6 [53.4; 55.9] minutes). There was a significant difference in the operation time between surgical procedures, but this was numerically not noticeable between the P-LRYGB (92.5 [91.2; 93.7]) and the R-LRYGB (90.5 [89.3; 91.8]), as shown in Table 4. As a consequence of a splenic lesion, one patient in the P-LRYGB group underwent conversion to an open procedure. The P-LMGB group (n = 1) also experienced a conversion to an open procedure. Consequently, the cumulative conversion rate for four surgical procedures was 1.1% (n = 2).

|

Method |

N |

Mean [Range of dispersion] (min) |

p-value * |

|

P-LRYGB |

59 |

92.5 [91.2; 93.7] |

|

|

P-LMGB |

16 |

68.6 [67.3; 69.9] |

|

|

R-LRYGB |

67 |

90.5 [89.3; 91.8] |

|

|

R- LMGB |

47 |

54.6 [53.4; 55.9] |

|

|

Total |

189 |

82.4 |

<0.001 |

|

* p-values pertaining to all four groups. |

|||

Table 4: Mean duration of primary and revision surgery (test on log-transformed values).

The overall rate of intraoperative complications was 3.2% (n = 6). There was just one relevant complication associated with the spleen injury, necessitating the conversion to open surgery. General complications arose in 3.2% (n = 6). The specific complication rate was 2.6% (n = 5). In two cases, gastroscopic intervention for anastomotic hemorrhage is required, whereas one patient necessitates laparoscopic intervention. The incidence of Anastomotic Insufficiency (AI) or Anastomotic Stricture (AS) was 0% across all surgeries according to the data (Table 5).

|

Complication |

Procedure |

p-value* |

|||||||

|

P-LRYGB |

P-LMGB |

R- LRYGB |

R- LMGB |

||||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

|

Intraoperative |

|||||||||

|

Spleen injury |

1 |

1.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.529 |

|

Others |

4 |

6.8 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.113 |

|

Total |

5 |

8.5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.045 |

|

General postoperative |

|||||||||

|

Total |

5 |

8.5 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.045 |

|

Specific complications |

|||||||||

|

Bleeding with gastroscopic treatment |

1 |

1.7 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.796 |

|

Bleeding operative revision |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

0.608 |

|

Peritonitis |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6.3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.012 |

|

Wound infection |

1 |

1.7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.529 |

|

Total |

2 |

3.4 |

1 |

6.3 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0.524 |

|

* p-values pertaining to all four groups. |

|||||||||

Table 5: Incidence of intraoperative and postoperative complications.

A patient developed peritonitis because of minor bowel leakage at the anchoring suture. The correction was performed laparoscopically with oversewing of the leak. The patients who had conversion to open surgery due to splenic injury need treatment for a wound infection. No mortality was observed in the investigated individuals. Table 6 presents the duration of hospitalization and postoperative stay.

|

Method |

Hospitalisation [d] |

Postoperative stay [d] |

|

|

N |

Mean [Range of dispersion] |

Mean [Range of dispersion] |

|

|

P-LRYGB |

59 |

5.5 [4.1; 6.9] |

4.6 [3.2; 6.0] |

|

P-LMGB |

16 |

5.9 [4.7; 7.1] |

4.9 [3.7; 6.1] |

|

R-LRYGB |

67 |

5.3 [4.0; 6.6] |

4.3 [3.0; 5.6] |

|

R-LMGB |

47 |

5.2 [4.0; 6.4] |

4.2 [3.0; 5.5] |

|

p-value |

0.293 |

0.147 |

|

|

Total |

189 |

5.6 |

4.6 |

Table 6: Hospitalization time and postoperative stay.

Reoperations During Hospitalization

During the hospital admission, six patients underwent relaparoscopy between 24 and 72 hours postoperatively. The causes included suture rupture leading to small intestinal leakage in two patients, subsequent hemorrhage in one patient, small bowel perforation in one patient, and undetermined explanations for elevated inflammatory symptoms in two patients. The reasons of suture rupture were adapted to the surgical technique and not to device. Among these circumstances, a P-LRYGB was conducted in four instances, while a P-LMGB and R-LRYGB were executed in one instance each. The reoperation rate during the hospitalization period was 3.2%.

Follow-Up

Reoperations were not necessary following release from hospitalization at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months.

After 20 months, a perforated jejunal peptic ulcer necessitated a relaparoscopy in one patient who had previously undergone LMGB. Biliary reflux led to the change from an LMGB to an LRYGB in two patients after 24 months. The total revision rate after 24 months was therefore 1.05%.

Discussion

In addition to Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), the LRYGB and LMGB are among the most frequently utilized techniques in Bariatric Metabolic Surgery (BMS). Both procedures are safe for their perioperative complication rates and beneficial in diminishing weight and comorbidities [20,21].

Standards related to surgical procedures have been established in recent years. This encompasses the antecolic-antegastric efficacy of gastroenterostomy. Closing the Petersen and Brolin area can substantially reduce the likelihood of internal hernias and subsequent postoperative ileus [22]. Laparoscopic gastroenterostomy and entero-enterostomy have been implemented in LRYGB utilizing stapler technology. Nonetheless, the application of robotic-assisted procedures has reinstated the significance of hand sewing in the performance of anastomoses [23].

For closing anastomoses, as well as for tension-retaining and anchoring sutures, a variety of suture materials are available on the market. In general, their utilization is contingent upon the expense of the suture material. This single-center trial, conducted by a single surgeon, utilized PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture as both a tension-retaining and anchoring suture. This investigation aims to determine whether the use of PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture leads to increased or decreased complications or prolonged hospital stays, in comparison to literature that does not involve it.

Duration of Hospitalization and Postoperative Length of Stay

At 5.6 days, the duration of hospitalization for all operations exceeds the worldwide benchmark. Nevertheless, the majority of research from Germany indicates a prolonged hospital stay following bariatric surgery, in contrast to international statistics, attributable to particular conditions. The COVID-19 pandemic further impacted this research during the designated time. Patients were prepped for surgery on the day of admission following the receipt of a negative coronavirus test result. As a result, it was not possible to perform surgical procedures on the day of admission. The mean postoperative length of stay was 4.6 days, which is within the DRG range for Germany[11]. The duration of the postoperative stay was affected by the coronavirus pandemic, resulting in limited discharge alternatives in cases of infection during the stay and by the supra-regional care mandate.

Complications

Intraoperative and postoperative Bleeding

Our patients experienced a total intraoperative and postoperative hemorrhage rate of less than 2%. During the postoperative period, two instances of hemorrhage were seen at the gastroenterostomy site. In one instance, the hemorrhage manifested on the day of the operation, whereas in the second instance, it occurred on the second postoperative day. In both cases, the gastroenterostomy underwent gastroscopic hemostasis via clip application. Since the PDS was not utilized for the gastroenterostomy, there is no association with the suture material utilized. The occurrence of bleeding at the gastroenterostomy is reported in the BMS as 1.1- 4.0% within the initial month following surgery [24,25]. On postoperative day 2, hemorrhaging necessitated a relaparoscopy in one case. No source of hemorrhage was identified intraoperatively. In the multimorbid patient, hemorrhaging from the staple line is the most probable etiology. This is also irrelevant to the suture content used. The literature implicates other factors in the development of postoperative hemorrhage. These consist of male gender, prior conditions, and medications [26]. In contrast to the literature, our analysis revealed that women experienced a higher incidence of both gastroscopic and laparoscopic revision hemorrhage (75%) than males (25%). Two patients exhibited an elevated prevalence of comorbidities. In one case, the surgery was conducted while the patient was still taking aspirin because of an already existing cardiovascular condition.

Incidence of Anastomotic Insufficiency or Stenosis

The incidence of anastomotic insufficiency or anastomotic stenosis was 0% across all surgeries according to the data. The analysis does not ascertain if the application of the PDSTM II Ethi-EndoClip Suture affects this finding. Nonetheless, it is evident that our patient population had a reduction in anastomotic insufficiency or anastomotic stricture compared to the current literature on the AI rates following bariatric surgery [27-29]. The introduction of an additional suture may decrease tension on the anastomosis, perhaps resulting in a reduction in AI.

Peritonitis

The data presented in this study indicated that 0.5% (n = 1) of the 189 patients in the patient population experienced complications related to suture material, which led to subsequent peritonitis. This was the result of a rupture of the minor curvature-side suture. Upon reflection, this was the result of either an incorrect application, a defect in the thread, or a surgical error. Nevertheless, the incidence of peritonitis in the individuals analyzed in this study was lower than the rate of peritonitis reported in the literature (up to 6%) following bariatric surgery, particularly RYGB [30,31]. Additionally, no peritonitis was documented in any of the patients that was caused by an infection resulting from the use of the PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture.

Study Limitations

The present investigation does not allow for the drawing of any conclusions regarding the use of PDSTM II as a suture material. A variety of factors typically influence the outcome of bariatric surgery, in addition to the technique and the material used. Additional limitations of the current study include the exploratory nature of the research, absence of a prespecified hypothesis, disparities in number of participants, representativeness of the sample relative to the target population, insufficient justification for sample size, and the lack of a control group for sutures.

Additionally, a single surgeon with extensive expertise conducted all procedures in a hospital. The surgeon’s experience significantly influences the intraoperative and postoperative outcomes, particularly in minimally invasive and robotic surgery. Consequently, it would be intriguing to determine whether the suture technique and suture material, or rather the surgeon’s experience, have a more significant impact on the outcome. This is the reason why multicenter studies should be conducted to establish a definitive statement regarding the impact of suture material and technique, involving a variety of surgeons with varying levels of surgical experience.

The conversion of SG into an LRYGB and into an LMGB, as well as both primary LRYGB and LMGB, are safe bariatric surgical procedures. The current analysis of PDSTM II Ethi-Endo-Clip Suture indicates that the use of a specialized suture material is not associated with an increased perioperative and postoperative complication rate in comparison to alternative traditional suture techniques and materials. This is contingent upon the expertise of the institution, as well as patient-related potential risks such as BMI, age, co-morbidities, and medical history.

References

- Schienkiewitz A, Kuhnert R, Blume M & Mensink GBM (2022) Overweight and obesity among adults in Germany – Results from GEDA 2019/2020-EHIS. Journal of Health Monitoring 7: 21-28.

- Overweight or obese population | OECD.

- Lee W & Almalki O (2017) Recent advancements in bariatric/metabolic surgery. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 1: 171-179.

- Eisenberg D (2022) 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 18: 1345-1356.

- Zhang Z, Miao L, Ren Z & Li Y (2021) Robotic bariatric surgery for the obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 35: 2440-2456.

- Fourman MM & Saber AA (2012) Robotic bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 8: 483-488.

- Fairag M (2024) Robotic Revolution in Surgery: Diverse Applications Across Specialties and Future Prospects Review Article. Cureus 16: e52148.

- Velardi AM, Anoldo P, Nigro S & Navarra G (2024) Advancements in Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Review of Laparoscopic and Robotic Techniques. J Pers Med 14: 151.

- Outcomes of bariatric surgery.

- Gulinac M (2023) Long-term effectiveness, outcomes and complications of bariatric surgery. World J Clin Cases 11: 4504-4512.

- Thaher O (2022) Is development in bariatric surgery in Germany compatible with international standards? A review of 16 years of data. Updates Surg 74: 1571-1579.

- Ghaferi AA (2021) Testing a Decision Aid to Help Patients Choose between Two Types of Bariatric Surgery.

- Neff KJ, Olbers T & le Roux CW (2013) Bariatric surgery: The challenges with candidate selection, individualizing treatment and clinical outcomes. BMC Med 11: 18.

- Ren CJ, Cabrera I, Rajaram K & Fielding GA (2005) Factors influencing patient choice for bariatric operation. Obes Surg 15 : 202-206.

- Bindal V, Sethi D & Pandey D (2021) Robotic primary bariatric surgery. Dig Med Res 4: 56-56.

- Barbat S, Nimeri A (2024) Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Handbook of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 147-160.

- Chen K (2016) Totally laparoscopic gastrectomy using intracorporeally stapler or hand-sewn anastomosis for gastric cancer: A single-center experience of 478 consecutive cases and outcomes. World J Surg Oncol 14: 115.

- Hashida H (2022) Intracorporeal reinforcing sutures reduce anastomotic leakage in double-stapling anastomosis for laparoscopic rectal surgery. Videosurgery and other Miniinvasive Techniques 17: 491-497.

- Yan JF (2020) Laparoscopic gastrectomy using intracorporeally handsewn anastomosis of esophagojejunostomy, gastroduodenostomy, or gastrojejunostomy for gastric cancer. Medicine 99: e19002.

- Velotti N, Vitiello A, Berardi G, Di Lauro K & Musella M (2021) Rouxen-Y gastric bypass versus one anastomosis-mini gastric bypass as a rescue procedure following failed restrictive bariatric surgery. A systematic review of literature with metanalysis. Updates Surg 73: 639647.

- Kermansaravi M (2021) One Anastomosis/Mini-Gastric Bypass (OAGB/MGB) as Revisional Surgery Following Primary Restrictive Bariatric Procedures: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg 31: 370-383.

- Cho M (2006) Frequency and management of internal hernias after laparoscopic antecolic antegastric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass without division of the small bowel mesentery or closure of mesenteric defects: review of 1400 consecutive cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2: 87-91.

- Vilallonga R (2015) Robotically Assisted Single Anastomosis Duodenoileal Bypass after Previous Sleeve Gastrectomy Implementing High Valuable Technology for Complex Procedures. J Obes 2015: 586419.

- Dick A, Byrne TK, Baker M, Budak A & Morgan K (2010) Gastrointestinal bleeding after gastric bypass surgery: nuisance or catastrophe? Surg Obes Relat Dis 6: 643-647.

- Kollmann L, Gruber M, Lock JF, Germer CT & Seyfried F (2024) Clinical Management of Major Postoperative Bleeding After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 34: 751-759.

- Santos-Sousa H (2024) Preoperative risk factors for early postoperative bleeding after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409: 163.

- Almby K & Edholm D (2019) Anastomotic Strictures After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: a Cohort Study from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry. Obes Surg 29: 172-177.

- Smith MD (2014) Technical Factors Associated with Anastomotic Leak after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 11: 313-320.

- Aleman R, Menzo E, Lo Szomstein S & Rosenthal RJ (2020) Efficiency and risks of one-anastomosis gastric bypass. Ann Transl Med 8: S7-S7.

- Montravers P (2013) Clinical Features and Outcome of Postoperative Peritonitis Following Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 23: 1536.

- Kassir R (2016) Complications of bariatric surgery: Presentation and emergency management. International Journal of Surgery 27: 77-81.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.