Severe Toxicities Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Are the Results Worth the Price?

by Chaviaropoulou A1,2*#, Argyriadis A2#, Kalfoutzos K2, Kosse J2,3, Braun S4, Jackisch C4,5,6

1Varisano Klinikum Hoechst GmbH, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Frankfurt-Hoechst, Germany

2Sana Klinikum Offenbach GmbH, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Offenbach, Germany

3Klinikum Hanau, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hanau, Germany

4Sana Klinikum Offenbach GmbH, Institute of Pathology, Offenbach, Germany

5Klinikum Essen Mitte, Essen, Germany

6OncoNet Rhein-Main e. V., Germany

*Corresponding author: Anastasia Chaviaropoulou, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Varisano Klinikum Hoechst GmbH Gotenstraße 6-8, 65929 Frankfurt, Germany

#Contributed equally

Received Date: 27 January 2025

Accepted Date: 31 January 2025

Published Date: 03 February 2025

Citation: Chaviaropoulou A, Argyriadis A, Kalfoutzos K, Kosse J, Braun S, et al (2025) Severe Toxicities Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Are the Results Worth the Price? Ann Case Report. 10: 2176. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102176

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have emerged as a promising therapeutic approach in the management of early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), significantly improving pathological complete response rates and survival outcomes. However, the use of ICIs is associated with a spectrum of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), ranging from mild symptoms to severe, lifethreatening toxicities. This case series reports the clinical course of three cases of patients with early- stage TNBC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy including ICIs who experienced severe toxicities, necessitating effective immunosuppressive therapy and discontinuation of systemic cancer treatment. Despite achieving a pathological complete or partial response following neoadjuvant systemic therapy (carboplatin/paclitaxel q1w with pembrolizumab q3w) and subsequent breast conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, the patients´ journey underscores the need for vigilant monitoring, multidisciplinary management, and judicious decision-making when incorporating ICIs into early TNBC treatment protocols. We observed in those three cases, with curative prognostic intention, irAEs ranging from CTCAE Grade III-IV including severe ARDS. Some of those irAEs were long lasting in nature. Our cases underscore the broad spectrum of immune-related side effects and emphasize the importance of early recognition, a multidisciplinary approach, and careful selection of patients who are most likely to benefit from this therapy.

Keywords: Checkpoint Inhibitors; Pembrolizumab; Adverse Events; Immunotherapy; Triple- Negative Breast Cancer.

Introduction

tumor type. A key breakthrough in this field was the identification Over the past decade, cancer immunotherapy has revolutionized of immune checkpoint proteins, potent suppressors of immune activity. This discovery spurred the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which block inhibitory pathways to restore T-cell function and enhance immune responses against tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) [1,2].

One of the most significant checkpoint blockade strategies targets the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). Under normal conditions, PD-1, a receptor expressed in T cells, plays a critical role in maintaining immune homeostasis by preventing excessive immune responses and autoimmunity. However, cancer cells exploit this pathway by upregulating PD-L1, which binds to PD-1 on T cells, resulting in T-cell inactivation and immune evasion [3].

Pembrolizumab, a recently developed ICI, selectively binds to

PD-1 receptors on T cells, blocking their interaction with PDL1. This action restores T-cell activity, enabling immune cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells. By disrupting the PD-1/ PD-L1 pathway, pembrolizumab enhances immune-mediated cytotoxicity and has shown particular efficacy in cancers with high PD-L1 expression or high tumor mutational burden, characteristics that render tumors more immunogenic [2,3].

Although breast cancer was initially considered an immunologically “cold” tumor, TNBC has emerged as an exception. TNBC exhibits a tumor microenvironment with elevated levels of stromal and tumor- infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and increased PD-L1 expression, making it particularly responsive to immunotherapy [4]. Pembrolizumab, in combination with chemotherapy, is now approved for patients with locally recurrent, unresectable, or metastatic TNBC with a combined positive score (CPS) of 10 or higher, as well as for early-stage, high- risk TNBC as neoadjuvant therapy. The KEYNOTE-522 trial demonstrated that pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy significantly improved pathologic complete response rates, a key indicator of treatment efficacy [5-10].

However, the growing use of ICIs has been accompanied by a rise in immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These adverse effects occur due to heightened immune activation, which may inadvertently target healthy tissues. The underlying mechanisms involve direct tissue effects of monoclonal antibodies and immunemediated responses triggered by T-cell activation. Common irAEs include dermatologic, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and hepatic toxicities, although virtually any organ system can be affected [6].

Approximately 60–70% of patients treated with pembrolizumab experience irAEs, ranging from mild and reversible to severe and potentially life-threatening and long-lasting toxicities. These events can occur early during treatment or as delayed complications, even months after therapy has concluded. A systematic review of 50 trials involving 5,071 patients reported a median incidence of grade 3-4 irAEs at 21% [7] (Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of the relevant information of the three cases.

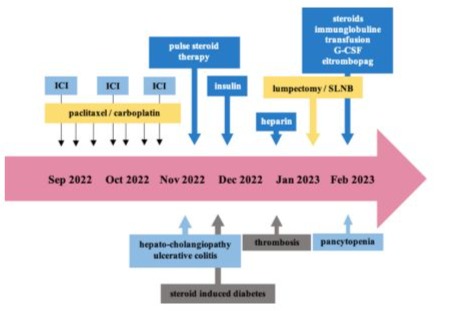

Figure 1: Course of Case #1.

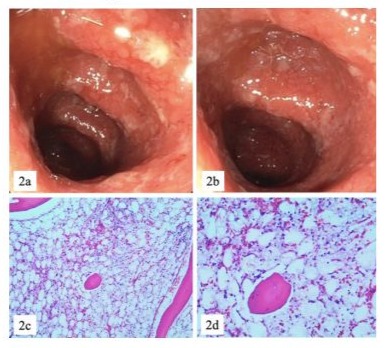

Figure 2: ICI induced ulcerative colitis CTCAE IV (2a, 2b) and pancytopenia / aplastic bone marrow CTCAE IV (2c, 2d).

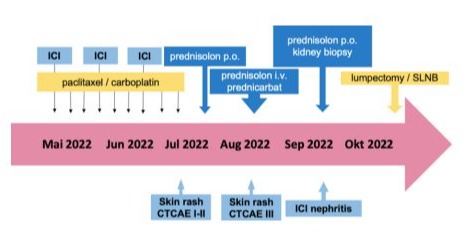

Figure 3: Course of Case #2

Figure 4: ICI induced dermatitis CTCAE III.

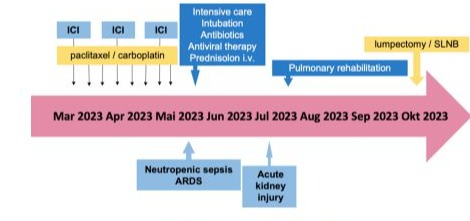

Figure 5: Course of Case #3.

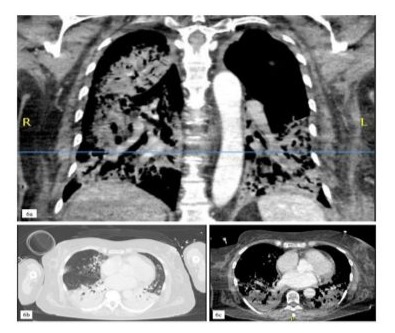

Figure 6: Pulmonary imaging findings presenting an acute, ICIinduced pneumonitis with a bacterial superinfection (6a-c).

Case Presentation

Case #1

A 44-year-old caucasian woman with a family history of breast cancer, otherwise healthy and without significant comorbidities, presented to our center with cT2, cN0 TNBC confined to the right breast. Following presentation in our multidisciplinary tumor board, the decision was to initiate neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy using pembrolizumab according to the KEYNOTE 522 protocol [5].

The patient then underwent surgery, including a lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Histopathological analysis revealed partial remission with final staging of ypT1b, ypN1a (1/5 sentinel nodes), L0, V0, Pn0, R0. Radiotherapy was administered, and post- neoadjuvant therapy with capecitabine was recommended following partial remission [8].

Three months after the onset of irAEs, the patient developed pancytopenia with aplastic bone marrow CTCAE grade IV (Figure 2). Treatment included antibiotics, blood transfusions, granulocyte colony- stimulating factor (G-CSF), dexamethasone, prednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulins, and off-label therapy with eltrombopag (initially 50, escalated up to 75mg/day). Given the severity of the adverse events, post-neoadjuvant systemic treatment with pembrolizumab and conventional chemotherapy was discontinued.

Case #2:

A 32-year-old caucasian woman presented with TNBC, clinical stage cT2N0, histological grade 3 (G3), a Ki-67 proliferation index of 90%, a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of 70%, a combined positive score (CPS) of 75, and an immune cell (IC) score of 2. Germline BRCA mutation testing was negative (gBRCAwt). The patient was treated with nine weekly doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel, along with three doses of pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks (Figure 3).

Following the third dose of pembrolizumab, the patient developed a skin rash graded as CTCAE Grade I-II, accompanied by minimal itching. Oral prednisolone (10 mg/day) was initiated but was progressively increased to 80 mg/day due to the persistence and worsening of the rash. As the rash progressed to CTCAE Grade III (Figure 4), the patient was hospitalized and treated with intravenous prednisolone (up to 120 mg/day), topical prednicarbate, and supportive therapies for itching and tingling.

The patient’s condition deteriorated, prompting a referral to our Department of Nephrology for further evaluation. During therapy with corticosteroids, the patient’s creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) indicated an acute kidney failure, classified as KDIGO Stage I and CTCAE Grade III. Further evaluation, including a kidney biopsy, confirmed immune checkpoint inhibitor ICI-induced nephritis. Prednisolone therapy was adjusted to 80 mg/day orally, and systemic cancer treatment was discontinued. The corticosteroid therapy was then

gradually tapered. Subsequently, the patient underwent a lumpectomy with SLNB, which revealed a pathologic complete response (ypT0, ypN0 with 0/2 sentinel nodes, ypL0, ypV0, ypPn0, ypR0). Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered following surgery. The patient was referred back to our nephrology department for ongoing consultation and has remained biochemically and clinically stable to date.

Case #3:

A 63-year-old caucasian woman presented with TNBC, histological grade 3 (G3), a Ki-67 proliferation index of 90%, gBRCA1/2wt, a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) of 0%, a combined positive score (CPS) of 10, and an immune cell (IC) score of 1. Her clinical staging was cT2, cN0. The patient began neoadjuvant therapy consisting of eight weekly cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel, combined with three doses of pembrolizumab 200 mg every three weeks (Figure 5).

After the third dose of pembrolizumab, the patient developed neutropenic sepsis and was admitted with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), characterized by a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of less than 70. A diagnostic workup revealed influenza-A pneumonia with bacterial superinfection by staphylococcus aureus and a high suspicion of autoimmune pneumonitis (Figure 6). Despite anti-infective treatment, the patient’s condition deteriorated, necessitating endotracheal intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation.

During the episode of neutropenic sepsis, the patient developed acute kidney injury, classified as KDIGO stage III, requiring continuous veno-venous haemodialysis (CVVHD) for three days. prednisolone therapy was initiated and gradually tapered as her condition improved, allowing for consideration of surgical intervention. During the same hospitalization, the patient was diagnosed with critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy, further complicating her clinical course.

Given the severity of immune-related and infectious complications, neoadjuvant therapy was discontinued. The patient subsequently underwent a lumpectomy with SLNB. Histopathological analysis revealed a partial remission (ypT1a, ypN0 with 0/2 sentinel nodes, ypL0, ypV0, ypPn0, ypR0). Postoperative systemic therapy was deemed contraindicated, and the patient proceeded with adjuvant radiotherapy.

Results

Managing these toxicities presents a significant clinical challenge, often requiring treatment interruptions, hospitalizations, or the discontinuation of immunotherapy. Here we present the management of three cases with severe irAEs associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in the neoadjuvant treatment of early-stage (cT2, cN0) TNBC. The first patient presented with an immune checkpoint inhibitor ICI-induced acute skin reaction (CTCAE Grade III) and acute renal failure related to ICI-induced nephritis. The second patient experienced hepato- cholangiopathy (CTCAE Grade IV), ulcerative colitis (CTCAE Grade IV), and delayed-onset, prolonged severe aplastic anemia (CTCAE Grade IV). The third patient developed severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis secondary to autoimmune pneumonitis (CTCAE Grade IV).

In all cases, corticosteroid therapy was initiated, as recommended by the ESMO [9] and ASCO [12,13] guidelines, and neoadjuvant systemic treatment was discontinued. Surgical outcomes revealed a pathological complete response (ypT0, ypN0) in the first case, partial remission (ypT1b, ypN1a) in the second case, and partial remission (ypT1a, ypN0) in the third case. None of the patients received any post-neoadjuvant systemic treatment. The addition of ICIs to conventional neoadjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to improve the clinical outcomes of patients with TNBC. However, multiple irAEs are common and may lead to therapy discontinuation and increased morbidity, potentially impacting therapeutic outcomes and survival negatively. The majority of patients treated with ICIs develop mild to moderate immunerelated side effects, with the most common being gastrointestinal, pulmonary, dermatological, and endocrine toxicities. Less frequent but potentially severe hematologic and neurologic toxicities may also occur, as ICIs can affect all organ systems.

Discussion

This paper provides critical insights into the onset and treatmentinduced severe immune- related adverse events associated with ICIs in the neoadjuvant treatment of early-stage TNBC, in a real world setting outside of clinical trials. While ICIs, particularly pembrolizumab, have revolutionized cancer therapy by enhancing immune-mediated tumor destruction, their use poses significant challenges.

TNBC is a highly aggressive breast cancer subtype characterized by the absence of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, which limits treatment options. The advent of ICIs has

transformed the therapeutic paradigm for TNBC by targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, a critical pathway for immune evasion by tumors. Pembrolizumab’s demonstrated efficacy in improving pathologic complete response (pCR) rates, particularly in highrisk early-stage TNBC, underscores its potential as a cornerstone in combination therapies, as evidenced in the KEYNOTE-522 trial [5]. Although pCR is a meaningful endpoint associated with improved survival, the ultimate goal remains long-term diseasefree and overall survival. The cases presented here highlight the need to balance these outcomes with the risk of severe irAEs.

The course of these three cases described above highlight the diverse spectrum of irAEs, which range from autoimmune pneumonitis to severe aplastic anaemia and hepato-cholangiopathy. These examples underscore the complexity and severity of irAEs, which can significantly affect patient outcomes if not managed appropriately. Effective management strategies must, therefore, include early identification of these adverse events, a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, and prompt interventions to mitigate potential lifethreatening consequences. Hence, the intervention in those three cases involved the immediate initiation of corticosteroids and the cessation of neoadjuvant systemic therapy. This strategy was pivotal in mitigating the severity of the irAEs, leading to partial or even complete resolution of the toxicities in some instances. These outcomes align with current guidelines, which recommend the judicious use of immunosuppressive therapies to control severe irAEs while trying to preserve the underlying anti-tumor immune responses. The goal is always to strike a balance minimizing the risk of life-threatening adverse effects without compromising the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Interestingly, despite the discontinuation of the neoadjuvant systemic therapy due to irAEs, one of the patients ultimately achieved a pathological complete response (pCR), while the others demonstrated partial remissions. These observations raise important clinical questions about the optimal duration and intensity of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-based regimens. Specifically, the findings suggest that some patients may still derive significant therapeutic benefit from relatively short courses of ICI therapy, even if treatment must be discontinued due to severe irAEs. This opens a broader discussion on whether shorter treatment courses could be an effective strategy for certain patients, potentially reducing the risk of severe adverse events while maintaining therapeutic efficacy. Ultimately, optimizing ICI therapy regimens while minimizing the risk of severe adverse events will be crucial for improving outcomes in patients with advanced cancer.

The findings highlight the need for careful patient selection in ICI-based therapy for early- stage TNBC. Biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression, tumor mutational burden, and stromal tumorinfiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are crucial for identifying patients most likely to benefit from these therapies. However, predicting susceptibility to severe irAEs remains a significant challenge due to their multifaceted and often unpredictable nature.

Another critical consideration is the long-term impact of irAEs on survival and quality of life. Severe toxicities, such as autoimmune pneumonitis or aplastic anaemia, may result in chronic sequelae, complicating subsequent treatments and survivorship care. These observations emphasize the need for ongoing research into mitigation strategies, including personalized immunotherapy dosing, improved biomarkers for irAE risk stratification, and novel agents that modulate immune activation more precisely.

Conclusion

This case study addresses both the promise and the challenges of ICIs in TNBC. While these agents have significantly expanded treatment options for an aggressive cancer subtype, their associated toxicities necessitate a nuanced approach to patient care. Future studies should focus on refining patient selection, optimizing treatment regimens, and developing robust management protocols for irAEs. Insights from this case series reinforce the importance of a multidisciplinary and patient-centered approach to maximizing the benefits of ICIs while minimizing their risks. Finally, this discussion evaluates the findings of the above-mentioned cases and contextualizes them within the broader landscape of TNBC treatment and immunotherapy to remind health care professionals to balance wisely between the anticipated options to optimize the prognosis of TNBC and the possible, partially life-threatening toxicity in a curative setting of early TNBC.

References

- Naimi A, Mohammed R. N, Raji A, Chupradit S, Yumashev AV, et al. (2022). Tumor immunotherapies by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): The pros and cons. Cell Communication and Signaling, 20: 44.

- Howard F. M, Villamar D, He G, Pearson A. T, & Nanda R. (2021). The emerging role of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs, 31: 531–548.

- Stanton S.E, Adams S, Disis M.L. (2016) Variation in the Incidence and Magnitude of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Systematic Review. JAMA Oncology, 2:13541360.

- Duan Q, Zhang H, Zheng J, Zhang L. (2020) Turning Cold into Hot: Firing up the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends C a n c e r , 6:605-618.

- Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, Pusztai L, McArthur H, et al. (2022) Eventfree Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 386:556-567.

- Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis G.P. Lamine F, Maillard M, et al. (2019) Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 16:563–580.

- Chen T.W, Razak A.R, Bedard P.L, Siu L.L, Hansen A. R. (2015) A systematic review of immune-related adverse events reporting in clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO, 26: 1824-1829.

- Masuda N, Lee S.-J, Ohtani S, Im Y, Lee E, et al. (2017). Adjuvant Capecitabine for Breast Cancer after Preoperative Chemotherapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 376:2147-2159.

- Haanen J, Obeid M, Spain L. Carbonnel F, Wang Y, et al. (2022) Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Annals of Oncology, 33: 1217-1238.

- Connors C, Valente S. A, Elsherif A, Escobar P, Chichura A, et al (2024) Real-world outcomes with the KEYNOTE-522 regimen in earlystage triple-negative breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 32: 912-921.

- Yan, T, Yu, L, Zhang, J, Chen, Y, Fu, Y, et al (2024) Achilles’ heel of currently approved immune checkpoint inhibitors: Immune-related adverse events. Frontiers in Immunology, 15: 1292122.

- Supportive Care and Management of Side Effects, AGO Guidelines 2024.

- Schneider B. J, Naidoo J, Santomasso B, Lacchetti C, Adkins S, et al. (2021) Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in patients treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor therapy: ASCO Guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39: 4073-4126.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.