Secondary Hemophagocytic Histiocytosis Arising from Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma

by Silvia Tse Bunting1*, Muhamed Baljevic2

1Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Microbiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

2Department of Hematology Oncology, Vanderbilt University of Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

*Corresponding author: Silvia Tse Bunting, Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Microbiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

Received Date: 30 November 2025

Accepted Date: 04 December 2025

Published Date: 08 December 2025

Citation: Bunting ST, Baljevic M. (2025). Secondary Hemophagocytic Histiocytosis Arising from Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Ann Case Report. 10: 2465. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102465

Abstract

We are reporting a case of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) arising in an undiagnosed multiple myeloma (MM), which is rarely reported as a cause of secondary HLH. HLH is a severe hyperinflammatory syndrome in the setting of immune dysfunction with concomitant immune system activation. It can lead to multiorgan failure and death if not treated promptly and appropriately. It is often treatable but still largely underdiagnosed due to overlapping clinical and laboratory findings with other clinical entities, especially in the intensive care setting, resulting in many unnecessary deaths. First was described in its primary, familial form (pHLH) and later secondary, acquired form (sHLH) was recognized. Secondary HLH results from infections, malignancies, autoinflammatory/autoimmune disease, or following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or CAR-T cell therapy. When associated with rheumatological diseases, it is termed macrophage activation syndrome. Although sHLH is most seen in adults, there is genetic predisposition to sHLH. While lymphoma has been more commonly observed hematologic malignancy associated with sHLH, MM as an underlying cause has rarely been reported. We report a case of sHLH arising from newly diagnosed MM which was successfully treated, with full clinical recovery 16 months after initial presentation.

Keywords: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; Plasma cell neoplasm; Untreated

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a severe hyperinflammatory syndrome in the setting of an immune dysfunction with concomitant immune system activation. It can lead to multiorgan failure and death if not recognized and treated promptly. HLH can be classified as primary (inherited, genetic) or secondary (acquired) HLH. The pathogenesis of primary HLH includes genetic defects in the perforin-dependent cytotoxic pathway and mutations affect activation of the inflammasome. These can cause irreversible immune dysfunction. Primary HLH includes several subcategories: familial, certain HLH with hypopigmentation and oculocutaneous and platelet function disorders, X-linked lymphoproliferative disorder (XLP-1) associated HLH, and inflammasome-associated HLH. The familial form most commonly affects children. The secondary HLH, also named acquired HLH, usually results from underlying infections, malignancies, autoinflammatory/autoimmune diseases, or following hematopoietic stem cell transplant or CAR-T cell therapy [1, 2]. When it is associated with rheumatologic diseases, it is termed macrophage activation syndrome. Immune dysfunction is characterized by reversible NK or CD8+ T cell dysfunction. T cell dysfunction is usually associated with viral infection or autoimmune diseases, while NK cell deficiency is usually associated with HLH post chemotherapy or during sepsis. B cell or T cell lymphomas are the most common cause of secondary HLH resulting from malignancy. However, sHLH caused by untreated multiple myeloma (MM) is rare with only three cases reported thus far [3, 4, 6]. We report a case of sHLH with CNS involvement secondary to previously undiagnosed MM which was successfully treated with MM-directed therapy. At the time of writing more than one year since the diagnosis, the patient is in hematoligc complete response on MM maintenance therapy, with notable resolution of severe (initially hemodialysis dependent) renal failure that was driven by sHLH/MM processes.

Case Report

64-year-old African American man with a past medical history of hypertension and alcohol use disorder was brought to emergency room (ER) for altered mental status. His chief complaint was rightsided flank and lower back pain x a few days. At the ER, he was febrile, hypotensive with blood pressure of 64/48 mmHg, and tachycardic with a heart rate of 138 bpm. Further work showed mild anemia and thrombocytopenia. The metabolic panel showed creatinine of 9.4 mg/dL and elevated liver enzymes (ALT 120; AST 507; D-bili 4.0; T-bili 5.2). He had an anuric acute kidney injury and was started on urgent hemodialysis. Due to reticulocytopenia, bone marrow biopsy was performed to rule out underlying bone marrow etiology.

Bone marrow biopsy showed mildly hypocellular marrow with trilineage hematopoiesis with erythroid hypoplasia and mild dysmegakaryopoiesis. There were increased plasma cells/ plasmacytoid lymphocytes. Scattered hemophagocytic histiocytes were present. Due to the presence of hemophagocytic histiocytes, review of the laboratory data showed markedly elevated Ferritin 167,500, Triglycerides 401. The combined clinical, laboratory, and bone marrow findings meet the criteria of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome (HLH) (HLH-2004) [5]. His CSF showed elevated protein and lymphocytes, consistent with CNS involvement by HLH.

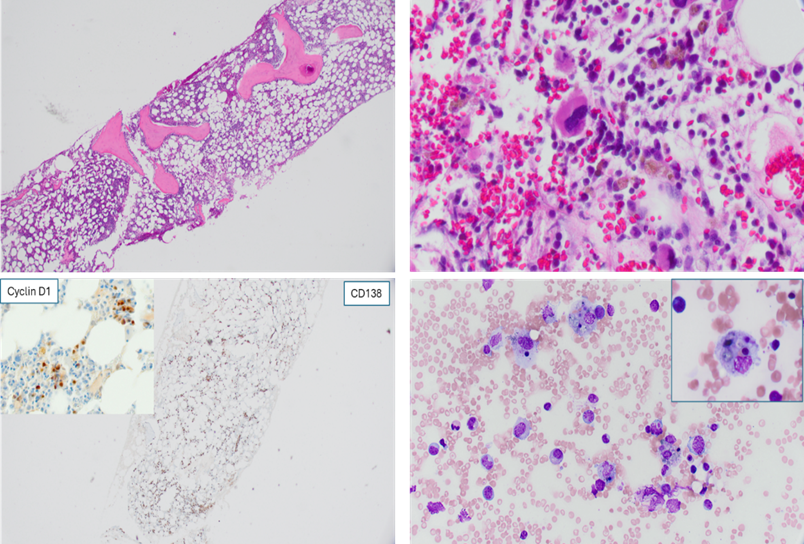

Due to the presence of bone marrow plasmacytosis, flow cytometric analysis showed a small population of cytoplasmic kappa light chain restricted aberrant plasma cells. No mature lymphoproliferative disorder was identified. The plasma cells were comprised of 10% of the cellularity, kappa-light chains restricted and positive for Cyclin D1 (Figure 1). There was no evidence of bone marrow amyloid deposition on Congo red stain. The FISH study identified CCND1/IGH fusion in 10% of the cells.

Figure 1: Bone marrow morphology. Upper left: H&E stain of the bone marrow core biopsy. Upper right: The core biopsy showed bone marrow trilineage hematopoiesis with focal increase of plasma cells in small clusters. Lower left: Immunohistochemical stains for CD138 highlighted the plasma cells throughout the marrow interstitium, focally forming small aggregates. Insect: the plasma cells were positive for cyclin D1 . Lower right: The bone marrow aspirate smear showed scattered hemophagocytic histiocytes.

Additional studies included a monoclonal band of the urine protein electrophoresis. An immunofixation study performed on the urine specimen showed an IgG Kappa clonal band. Serum protein electrophoresis showed excess kappa without a definite band. Serum free light chain assessment demonstrated elevation of kappa light chains (89.6 mg/dL) with a K/L ratio of 9.4. Subsequent skeletal survey showed no evidence of lytic lesions.

The patient was initially treated with HLH-directed therapy with dexamethasone and anakinra, but after the bone marrow results became available, the suspicion was present for a possible clonal plasma cell disorder as a driving factor for sHLH. As such, patients’ treatment was switched to the plasma-cell focused regimen with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (VCd). During his hospitalization course, the patient responded remarkably well, with resumption of urine production, cessation of renal replacement therapy with hemodialysis, > 90% reduction in serum ferritin, and significant improvement in clinical disposition. Due to insurance restrictions, the patient continued with the VCd based plasma cell directed therapy in the outpatient setting, with ultimately complete normalization of serum creatinine, 2 months after the initial presentation.

While our patient had the presence of Kappa-restricted plasma cells in his bone marrow, it was not clear whether the underlying plasma cell disorder represented symptomatic MM, light-chain amyloidosis or light-chain deposition disease. Due to social constraints and limitations as well as patient preferences, it was initially not possible to pursue the fat pad or kidney biopsy for further delineation of the underlying plasma cell disorder. The patient ultimately agreed to undergo the fat pad biopsy nearly a year after the initial presentation, which was negative for amyloid deposition. Subsequent additional whole-body imaging with low dose CT and PET/CT were also negative for any lytic or extramedullary lesions. Ultimately, a year and a half after the initial presentation, the patient agreed to undergo the MRI of the thoracolumbar spine, which showed several lesions of variable sizes throughout the thoracolumbar spine suspicious for MM involvement, ultimately establishing the MM as the subtype of underling causative plasma cell disorder.

Patient continues to do well and remains in presumed (bone marrow conformation deferred due to patient preferences) complete response on bortezomib maintenance therapy year and a half later, with low level ferritinemia which has nadired and persists in 1,300-1,400 ng/mL range (reference 24-336 ng/mL).

Discussion

We report a case of previously undiagnosed MM presenting with dialysis-dependent renal failure as an underling cause of sHLH. Secondary HLH can be associated with hematologic malignancies with lymphoma being the most common.

Literature research in PubMed for “hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and plasma cell myeloma” found nine (9) articles by citation matching, among which, six (6) articles were case reports for patients who had been actively treated for MM, either with chemotherapy, CAR-T or autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Chemotherapy and ASCT are known to cause sHLH, thus it is difficult to be certain that sHLH were associated with MM or MM related therapies. Three (3) were case reports of HLH secondary to newly diagnosed MM; [3, 4, 6]. Mendes et al. [3] reported a 64-year-old man who presented with fatigue, malaise, intermittent fever and weight loss for a duration of three months. The patient was diagnosed with plasma cell myeloma two weeks prior to presentation at a different hospital. After extensive work up, it was confirmed that the patient had HLH secondary to MM. He was treated with MM-directed therapy (methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone). Unfortunately, he died 15 days after hospitalization from renal failure. [4] Xu et al. reported a 57-year-old woman presented with night sweat, weight loss, fever, and bicytopenia. Blood tests showed anemia and thrombocytopenia, IgG lambda paraprotein, elevated ferritin, elevated triglyceride, and normal fibrinogen. Bone marrow biopsy showed 20% lambda restricted plasma cells. Plasma cell enriched FISH showed TP53 deletion. PET/CT showed diffuse marrow uptake and hepatosplenomegaly. The patient met the diagnostic criteria per HLH-2004 guideline. Other causes for sHLH were excluded. The patient was treated with MM targeted therapy followed by ASCT and achieved complete remission and complete resolution of organomegaly and cytopenia.

Plasma cell neoplasm arises from the monoclonal expansion of post-germinal-center, class-switched, terminally differentiated B cells that in most instances secrete monoclonal immunoglobulins. Immune dysregulation is a hallmark of clinically active MM. Interactions between malignant clonal cells and immune cells within the bone marrow microenvironment are associated with the formation of milieu favorable to immune dysregulation and tumor progression. It is believed that a failure to properly regulate the immune system, resulting in the persistent activation and proliferation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and macrophages ultimately results in a massive release of inflammatory cytokines (a “cytokine storm”), which could be responsible for the severe symptoms of HLH. As with other sHLH etiologies, high level of awareness, early recognition and intervention can lead to favorable clinical outcomes as witnessed in our case.

References

- Cordas Dos Santos DM, Tix T, Shouval R, Gafter-Gvili A, Jean-Baptiste A. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of nonrelapse mortality after CAR T cell therapy. Nat Med, 30: 2667–2678.

- Sepulveda FE, de Saint BG. (2017). Hemophagocytic syndrome: primary forms and predisposing conditions. Curr Opin Immunol, 49: 20-26.

- Mendes FR, Sobral KM, Culler HF, Couto SCF, Pereira J, et al. (2020). Acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as initial manifestation of multiple myeloma: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore), 99: e22299.

- Xu K, Childerhouse A, Kyriakou C. (2025). IgG Lambda Myeloma Presented With Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) Successfully Treated With VTD Induction and Melphalan Autograft. EJHaem, 6: e70176.

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, et al. (2007). HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 48: 124-131.

- Al-Ammari M, Hsu D, Bryant A. (2024). Myeloma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis - A comprehensive case study and a novel chemotherapy-free approach with anakinra. EJHaem, 5: 1057-1062.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.