Satisfaction After Patient-Specific Molding of Congenital Auricular Deformations

by Alexander L. L. Denis1-4*, Erni C. Mellema2-4, Alies Y bema2-4, Karlijn J. van Stralen3, Maurice M. Y. Mommaerts1,5, Hylke J. Schouten 2,3,4,6

1European Face Centre, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

2MKA Kennemer & Meer, Haarlem, Netherlands

3Spaarne Gasthuis Haarlem, Haarlem, Netherlands

4Red Cross Hospital, Beverwijk, Netherlands

5Private Clinic Face Ahead Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

6OLVG, Amsterdam, Netherlands

*Corresponding author: Alexander Denis, Universitair Ziekenshuis Brussel, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, 1090 Brussels, Belgium

Received Date: 12 August 2025

Accepted Date: 18 August 2025

Published Date: 20 August 2025

Citation: Denis ALL, Mellema EC, Bema AY, Stralen KJV, Mommaerts MMY, et al. (2025) Satisfaction After Patient-Specific Molding of Congenital Auricular Deformations J Surg 10: 11420 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011420

Abstract

This study assesses the effectiveness of ear molding in treating congenital auricular deformities and explores factors influencing treatment outcomes and immediate and long-term parental and surgeon satisfaction. Infants with auricular deformities who received ear molding treatment between January 2017 and October 2022 were included. Immediate post-treatment satisfaction was evaluated using a Likert 5-scale questionnaire. A follow-up assessment using the same scale was conducted in January and February 2023 to gauge long-term parental satisfaction. Data analysis includes correlations between factors including age, gender, deformity type, splint use, and treatment duration with treatment outcomes. Immediate post-treatment satisfaction revealed significant associations between younger age at treatment initiation, male gender, and higher parental satisfaction. Long-term follow-up indicated that most parents considered the procedure worthwhile. Lop ear deformity showed a significant association with better immediate and long-term outcomes in comparison to Stahl and prominent ears. Parental satisfaction remained high in the long term, suggesting that ear molding may reduce the need for future surgical interventions. This study supports that using a patient-specific molds is a cost-effective and non-invasive treatment option for congenital ear anomalies, potentially reducing the need for surgical intervention.

Keywords: Congenital Abnormalities; Conservative Treatment; Ear Cartilage; Infant, Newborn; Splints

Introduction

Congenital ear anomalies refer to malformations or deformations of the ear [1]. Deformations can occur due to external forces during pregnancy or after birth, without altering the amount nor quality of the chondro-cutaneous tissue1. Examples of deformities include prominent ears, helical rim anomalies, Stahl’s deformation (also known as “Spock ear”), cup or lop ear, and cryptotia. The incidence of auricular deformities ranges from 1 to 58% [2,3]. with self-correction rates varying from 30 to 84%, depending on the type of deformation. Prominent ears may even progress after birth [3-5].While ear deformations are generally neither harmful nor affect hearing, they can lead to low self-esteem and negative social feedback [6,7]. Surgical correction through otoplasty is possible when the ear is greater than 90% of the adult size, typically at the age of 5-6 years [8]. However, otoplasty has its cost and carries potential complications such as necrosis, wound infection, scar hypertrophy and keloid formation, hypersensitivity, and especially asymmetry [9]. To avoid surgical treatment, ear deformities can be treated conservatively with a patient-specific mold. This technique, first described by Matsuo et al., has been adjusted by other clinicians [10,11]. Initiation of treatment is recommended within the first six weeks of life when the pinna is most pliable, in conjunction with increased estrogen levels after birth 6. A patient-specific mold seems most effective, as standardized molds may be less suitable due to variety of ear shapes [12]. Studies [2,13-20] show that molding is a safe and effective method for treating congenital auricular deformities, however there is a lack of data on long-term outcomes and optimal timing and duration of treatment. The aim of the study is to investigate parents and surgeons’ satisfaction rates immediately after treatment, and parents’ satisfaction rate over time, to examine if molding prevents the need for future surgery. The study also explores the correlation between various factors, such as timing and length of treatment, type of deformity, gender, and the use of a splint.

Material and Methods

Infants with auricular deformities who received ear molding treatment at the Department of Maxillo-Facial Surgery in the Red Cross Hospital Beverwijk and Spaarne Gasthuis Haarlem, located in the Netherlands, were included. Referrals were made by pediatricians, midwives, general practitioners, or parents who noticed the deformities themselves. The inclusion period ranged from January 2017 to October 2022. Exclusion criteria encompassed systemic diseases, syndromes, and infants older than 6 weeks. Three surgeons of the team MKA Kennemer & Meer employed ear molding techniques, as described by Matsuo et al [10] and further popularized by Tan et al [6]. Steri-Strips (3M, St Paul, MN) strips were used in combination with a splint when necessary. The splint consisted of a soldering wire core segment enclosed within an 8 French polyethylene suction catheter (Figure 1). It was customized to maintain the ear in its correct position and secured to the helical rim using Steri-Strips (Figure 2). In cases with prominent ears, the ear was taped against the mastoid [6]. Parents were educated about the molding technique and instructed to reapply the devices if they came off. The duration of treatment was at least twice the age of the infants measured in days at the start of the treatment to ensure optimal results. For instance, an infant presented at the consultation at the age of 10 days would be treated for a total of 20 days. Upon completion of the treatment, satisfaction with the outcome was assessed by both the treating surgeon and the parents using a Likert 5-scale questionnaire. Feedback was provided for each pathology per ear. Each pathology received a single score, given either by the mother, father or both together. No distinction was made between the evaluations by the mother, father or both together. The scale ranged from “excellent” to “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “very poor”. Treatment was deemed successful if the result was rated 3 or more. Between January 2023 and February 2023, all parents were interviewed about their satisfaction with their children’s ears and whether they considered the procedure successful over time. Parents were asked to rate the difficulty of the treatment, classifying it as simple, mediocre, or difficult. They were also inquired about any complications.

Figure 1: Materials used for the treatment: Steri-strips, soldering wire core segment enclosed within an 8 French polyethylene suction catheter, and a ruler for scale.

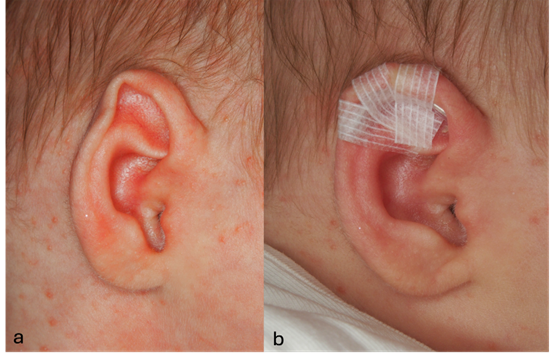

Figure 2: Example of treatment. (a) Stahl deformation before treatment. (b) Stahl deformation during treatment.

Ethical Approval

All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Spaarne Gasthuis Hospital in Haarlem, the Netherlands (nr 2022.0110) as well as the institutional review board of the Red Cross Hospital in Beverwijk, the Netherlands (nr. 24.027).

Statistical Method

Descriptive statistics were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0. We calculated frequencies and means (with standard deviations) by satisfaction scores. For dichotomous variables we calculated p-values using chi-square tests while we performed linear regression analyses for continues variables. P values below <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 50 infants with the age of four months or younger, having 70 auricular deformities of which 30 unilateral and 20 bilateral were included. 40 (45.5%) ears were prominent, 2 (2.3%) had helical rim anomalies, 15 (17.0%) Stahl’s deformation (‘Spock ear’), 31 (35.2%) were cup or lop ears, 0 cryptotia and 0 had other undefined deformations. 18 ears had multiple diagnoses (12 prominent and lop, 4 prominent and Stahl, 2 lop and Stahl). Treatment took place at a median age of 24 days with a range of 2 to 46 days. The duration of treatment was a median of 28 days (range 10 to 60). Helical rim anomalies were excluded from the analysis due to their low occurrence rate.

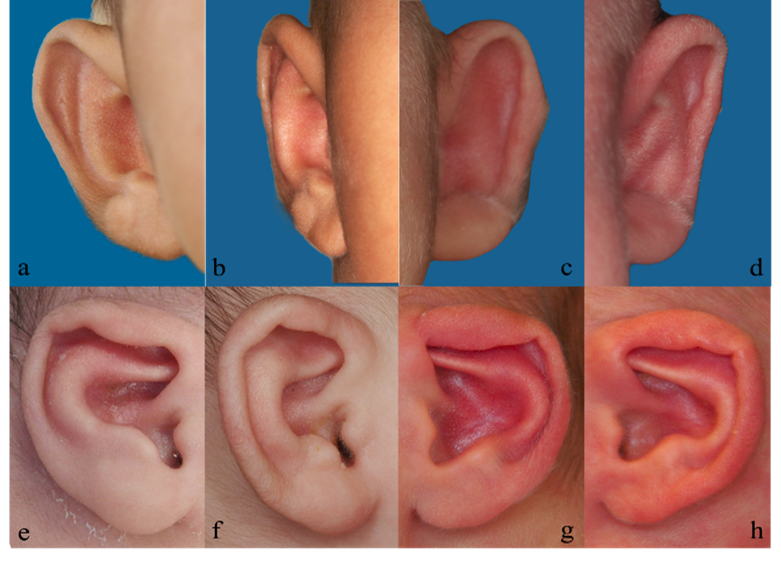

Outcome of Parents’ Satisfaction Directly after Treatment

After completion of the treatment, a total of 48 parents evaluated the outcome. The result of 34 (52%) ears were scored excellent, 13 (20%) good, 9 (14%) fair, 5 (8%) poor, 4 (6%) were very poor results and 3 were not assessed (Figure 3). For 2 ears with multiple deformities, the prominence was evaluated as good, but the lop deformity in one ear and the Stahl’s deformity in the other were scored as poor. The analysis indicated a significant association between a younger age at the start of treatment and a higher rate of satisfaction immediately after the procedure (p=0.03). Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between the male gender and a higher rate of satisfaction (p=0.047). However, there were no significant associations observed between the use of a splint and the duration of treatment with improved outcomes (p=0.39 and p=0.23, respectively). The results are presented in Table 1. Regarding specific deformities, neither prominent ears nor Stahl deformation demonstrated significant improved outcomes (p=0.69 and p=0.36, respectively). Conversely, lop ears showed a significant association with improvement (p=0.013). There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction when comparing patients with only a Stahl deformity, only lob ears, only prominent ears, or a combination of these deformities (overall p=0.18). The results are presented in Table 2.

Figure 3: Examples of evaluated patients directly after treatment. (a) Prominent ear before treatment. (b) Prominent ear evaluated as excellent immediately after treatment. (c) Prominent ear before treatment. (d) Prominent ear evaluated as good immediately after treatment. (e) Lop ear before treatment. (f) Lop ear evaluated as fair immediately after treatment. (g) Lop ear before treatment. (h) Lop ear evaluated as poor immediately after treatment.

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

|

Ears |

34 |

13 |

9 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Age |

19 (9.8) |

22 (10.2) |

31 (4.5) |

27 (5.2) |

20.5 (4.7) |

0.03 |

|

Duration |

31.7 (9.7) |

39.3 (15.0) |

41.9 (23.6) |

33.6 (7.7) |

32.0 (5.4) |

0.23 |

|

Gender |

|

|||||

|

Female |

7 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

0.047 |

|

Male |

27 |

8 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Splint |

||||||

|

Yes |

17 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

0.39 |

|

No |

17 |

8 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

Additional factors; age, gender, splint, duration of treatment. Age and duration in days. The mean value for each factor is given with the standard deviation in brackets.

Table 1: Satisfaction of the parents directly after the procedure in correlation with additional factors.

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

|

Ears |

34 |

13 |

9 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Prominent ear |

||||||

|

Yes |

15 |

8 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

0.69 |

|

No |

17 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Lop |

||||||

|

Yes |

14 |

10 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

0.013 |

|

No |

18 |

3 |

7 |

1 |

4 |

|

|

Stahl |

||||||

|

Yes |

9 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0.36 |

|

No |

23 |

12 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

|

|

Combination |

6 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0.18 |

|

Stahl only |

7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Lob only |

9 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Prominent only |

10 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

Type of deformation; prominent, lop or Stahl ear. Combination involves two types of deformities.

Table 2: Satisfaction of the parents directly after the procedure in correlation with type of deformation.

Outcome of Surgeons’ Satisfaction Directly after Treatment

The assessment by the surgeons revealed that 29 ears (54.7%) were rated as excellent, 10 (18.9%) good, 8 (15.1%) fair, 3 (5.7%) poor, and in 3 ears (5.6%) surgeons rated the result very poor (see Table 2). Additionally, 15 ears were not assessed for the outcome. Notably, in two cases, the prominence of the ears was satisfactorily resolved, while the lop ear aspect remained unresolved. No significant associations were found between age and gender regarding the outcome (p=0.12 and p=0.096, respectively). Furthermore, the use of a splint and the duration of treatment did not exhibit a significant correlation with improved outcomes (p=0.81 and p=0.28, respectively). The results are presented in Table 3. Different types of deformations, including prominent ears, Stahl deformation, and lop ears, were not associated with better outcomes (p=0.80, p=0.07, and p=0.53, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction when comparing patients with only a Stahl deformity, only lob ears, only prominent ears, or a combination of these deformities (overall p=0.45). The results are presented in Table 4.

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

|

Ears |

29 |

10 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Age |

19.7 (10.3) |

26.9 (5.7) |

31.5 (4.4) |

18.3 (14.8) |

22.7 (2.3) |

0.12 |

|

Duration |

32.4 (9.7) |

43.7 (15.9) |

40.1 (24.6) |

39.7 (10.7) |

33.3 (5.8) |

0.28 |

|

Gender |

||||||

|

Female |

7 |

2 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

0.096 |

|

Male |

22 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Splint |

||||||

|

Yes |

14 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0.81 |

|

No |

15 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

Additional factors; age, gender, splint, duration of treatment. Age and duration in days. The mean value for each factor is given with the standard deviation in brackets.

Table 3: Satisfaction of the surgeons directly after the procedure in correlation with additional factors.

|

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

Ears |

29 |

10 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Prominent ear |

||||||

|

Yes |

13 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

0.8 |

|

No |

15 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Lop |

||||||

|

Yes |

11 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0.07 |

|

No |

17 |

4 |

6 |

0 |

3 |

|

|

Stahl |

||||||

|

Yes |

8 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0.53 |

|

No |

20 |

9 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Combination |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0.45 |

|

Stahl only |

7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Lob only |

7 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Prominent only |

10 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

Type of deformation; prominent, lop or Stahl ear. Combination involves two types of deformities.

Table 4: Satisfaction of the surgeons directly after the procedure in correlation with type of deformation.

Outcome of Parents’ Satisfaction at Follow-Up

After a median follow-up of 2 years (range: 4 months to 70 months), parents were surveyed regarding their satisfaction of their children’s ears. A total of 64 parents (91.4%) considered the procedure to be worthwhile. The majority of parents (74%) reported no changes since the completion of the procedure, while 12% noted further improvement, and 10% observed a worsening of the ears. Parents perceived the procedure as simple in 67% of cases, mediocre in 11%, and difficult in 21%. During the follow-up assessment, parents rated the results as excellent in 30 (46%) ears, good in 24 (34%) ears, fair in 5 (7%) ears, poor in 5 (7%) ears, and reported very poor results in 4 (6%) cases (see table 3). 26% reported complications such as loosening of the Steri-Strips, pain, or skin irritation. In 17% of cases, parents considered a surgical intervention. The age and gender of the infants, the use of a splint and the duration of therapy were not significantly related to improved outcomes (p=0.97, p=0.08, p=0.48 and p=0.42 respectively). The results are presented in Table 5. Among the different types of deformations, only lop ear deformity demonstrated a significant association with a improvement (p=0.03), while prominent ears and Stahl deformation did not show improvement (p=0.13 and p=0.53, respectively). The results are presented in Table 6.

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

|

Ears |

32 |

24 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Age |

21.9 (10.9) |

24.5 (8.4) |

18.0 (10.2) |

22.8 (5.0) |

22.3 (2.1) |

0.97 |

|

Duration |

37.2 (13.8) |

32.8 (15.6) |

25.2 (3.8) |

37.3 (8.1) |

35.5 (6.4) |

0.42 |

|

Gender |

||||||

|

Female |

9 |

9 |

4 |

0 |

2 |

0.08 |

|

Male |

23 |

15 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

|

|

Splint |

||||||

|

Yes |

16 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0.48 |

|

No |

16 |

13 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

Additional factors; age, gender, splint, duration of treatment. Age and duration in days. The mean value for each factor is given with the standard deviation in brackets.

Table 5: Satisfaction of the parents at follow-up and correlation with additional factors.

|

|

Excellent |

Good |

Fair |

Poor |

Very Poor |

P-value |

|

Ears |

30 |

24 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Prominent ear |

||||||

|

Yes |

14 |

16 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

0.13 |

|

No |

16 |

8 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Lop |

||||||

|

Yes |

16 |

11 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0.03 |

|

No |

14 |

13 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

|

|

Stahl |

||||||

|

Yes |

8 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0.53 |

|

No |

22 |

20 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

|

|

Combination |

8 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0.06 |

|

Stahl only |

5 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Lob only |

10 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Prominent only |

7 |

9 |

0 |

5 |

3 |

Type of deformation; prominent, lop or Stahl ear. Combination involves two types of deformities.

Table 6: Satisfaction of the parents at follow-up and correlation with type of deformation.

Comparison of Satisfaction Directly after Surgery and at Follow-Up

Most scores were the same directly after surgery as compared with later (32/65, 49%). For 15 (23%) ears parents were less satisfied, and for 18 (28%) ears, parents expressed greater satisfaction compared with right after surgery. Older age (p=0.004) at time of treatment and longer duration (p=0.02) of treatment had a significant positive progression of satisfaction over time. Prominent ears had a significant (p=0.02) change over time, either positive or negative. Other deformations were not significantly associated with change over time. Results are presented in Table 7.

|

Worsened |

Same |

Improved |

P-value |

|

|

Overall |

23% |

49% |

28% |

|

|

Age |

17.1 |

21.6 |

27.5 |

0.004 |

|

Duration |

30.8 |

32.4 |

43.3 |

0.02 |

|

Female gender |

17% |

44% |

39% |

0.3 |

|

Stahl |

14% |

71% |

14% |

0.13 |

|

Lop |

20% |

47% |

33% |

0.67 |

|

Prominent |

31% |

31% |

37% |

0.02 |

Comparison of the additional factors; age, female gender, duration of treatment. Age and duration in days. Stahl, lop and prominent ears were also compered over time. P-value for factors affecting the change of improvement.

Table 7: Comparison of satisfaction directly after surgery and at follow-up.

Discussion

Congenital ear anomalies, including malformations and deformations, can have a significant impact on an individual’s self-esteem and social interactions. Surgical correction through otoplasty has traditionally been the main treatment option for auricular deformities. As an alternative, conservative treatment through molding the ear with a patient-specific mold has been explored. Although ear molding has been known since the 1980s, the acceptance is hindered by the delay in diagnoses, the assumption that these deformities will self-correct, accessibility and suitability of molds [3,10-21]. These factors lead to delayed and inadequate treatment with undesirable results. Hyaluronic acid levels, contributing to the elasticity of cartilage, are increased by maternal estrogen levels. These estrogen levels decrease after birth and are similar to older children after 6 weeks, decreasing the pliability and thereby the possibility of changing the auricular shape [6-22]. Consequently, treatment should be done during the first 6 week after birth. Maternal breastfeeding could extend this period to mold through estrogens in maternal milk [3]. There is limited data on the long-term outcomes and optimal timing and duration of treatment.

Concerning the satisfaction immediately after treatment, using a patient-specific mold, Nigam, et al. [18] observed a significantly higher satisfaction when treatment was initiated within the first 3 weeks of life. This was in correlation with our study where younger age was significantly associated with higher rates of satisfaction. Nevertheless, Dinis, et al. [17], who did not use a patient-specific mold, did not identify a significant correlation between a younger age at start of treatment and enhanced satisfaction.When comparing specific deformities, Chan et al [13] did not find a correlation within subgroups using a standardized molding system. However, our study showed that lop ears had a significant association with better outcomes in contrast to prominent ears and Stahl deformation. This suggests that lop ears are more likely to gain better results by molding therapy. Additionally, in our study, male infants were more likely to have higher rates of satisfaction, suggesting that parents are more critical to score the satisfaction of esthetics in girls than in boys. Surgeons’ satisfaction did not show a significant association but there is a clear trend that lop ears are more likely to give satisfactory results in contrast to other deformities. Similar as the parental satisfaction directly after treatment, lop ear deformity showed a significant association with better outcome at follow-up.

Also, a notable trend emerges indicating that parental satisfaction is generally higher for boys than girls, suggesting a potential gender bias in the evaluation of aesthetic outcomes. When contemplating the stability of the treatment over time, a comparison of both short-term and long-term follow-up data reveals a mere 0.9% variance in satisfaction. This suggests a sustained stability of treatment over time. These results contribute to our understanding of the treatment’s enduring impact and its reliability over time. The study of Zhong et al. [14] reported that the long-term success of prominent ears decreased significantly from 100% to 66,7%. Other deformities stayed stable over time [14]. Our study showed that patients with prominent ears more often had a change over time, either positive or negative. Approximately two-thirds of the ears showed a change. This was very different compared with for example patients with Stahl ears as in this group only 28% had a change in either direction after treatment. These findings imply that prominent ears may exhibit a lower degree of responsiveness to ear molding therapy, rendering them more susceptible to selfcorrection or relapse. Notably, children who were older at time of treatment, or had a longer duration of treatment more often had positive results over time. This contrasts with the significant higher rate of satisfaction noticed immediately after treatment when started at younger age. It implies that deformities in those who received treatment at a later age may have primarily less severe ear abnormalities.Furthermore, only 17% of the parents expressed a willingness to consider surgical intervention in the future. No other studies explored the need for further surgery. Taking into account the self-correction rates ranging from 30% to 84%, depending on the specific deformity, it can be suggested that the implementation of molding techniques reduces the likelihood of future surgical interventions [3-5]. There are two major categories of ear molding systems in practice: patient-specific molds and standard molds. This latter type, as highlighted by Zhao et al [12], does not accommodate all types of ear deformations and are also costly compared to patient-specific molds. In a study by Dinis et al [17], where standardized molding devices were employed, 51.1% of parents expressed the need for earlier follow-up due to issues such as the ear mold becoming loose or soiled. Furthermore, 46% of participants experienced dermatitis, skin excoriations, or pressure ulcers following the use of standardized systems [13]. In contrast, we observed that 21% of parents encountered difficulties with the application of the splint and Steri-Strips and only 26% reported complications. These findings imply that the utilization of patient-specific molds is associated with fewer complications and greater ease of handling compared to standardized molds. It is noteworthy that lop ear deformity showed significantly better outcomes, whereas prominent ears and Stahl deformation did not. This suggests that the effectiveness of the molding technique may vary depending on the specific type of deformity. Further research is needed to explore the underlying factors contributing to these differences and to optimize treatment strategies for different auricular deformities.Long-term follow-up assessment indicated that the majority of parents considered the procedure to be worthwhile. However, a small percentage of parents expressed a willingness to consider surgical intervention.

This suggests that while the molding technique may be effective in many cases, surgical correction may still be necessary for some individuals.It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The sample size was relatively small, and the study was conducted at only two institutions, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study focused on parental and surgeon satisfaction as the primary outcome measures. No distinction was made between the evaluation by the father, mother, or both together. Objective assessments of ear morphology and functional outcomes were not included.In conclusion, the results of this study support the use of patient-specific molds for the conservative treatment of congenital auricular deformities. The molding technique demonstrated a high rate of parental satisfaction immediately after treatment, with younger age and male gender associated with higher rates of satisfaction. Lop ear deformity showed a significant association with better outcomes. However, further research is needed to optimize treatment strategies for different types of deformities and to assess long-term objective outcomes. The conservative approach using patientspecific molds may prevent the need for surgical intervention in many cases, providing a less invasive, simple, safe, and potentially cost-effective treatment option for congenital ear anomalies. This procedure should be offered more to parents with affected infants, and they should be informed about this possibility before birth to prevent treatment delay. Declarations

Funding: None

Competing Interests: None

Ethical Approval: Ethical committee approval was granted by the institutional review board of the Spaarne Gasthuis Hospital in Haarlem, the Netherlands (reference number 2022.0110) as well as the institutional review board of the Red Cross Hospital in Beverwijk, the Netherlands (nr. 24.027).

Patient Consent: No written patient consent has been obtained. An oral consent was given after sending patient information and informed consent to their home and confirming it after a telephonic contact.

References

- Tan ST, Abramson DL, MacDonald DM, Mulliken JB (1997) Molding therapy for infants with deformational auricular anomalies. Ann Plast Surg 38: 263-268.

- Schonauer F, La Rusca I, Molea G (2009) Non-surgical correction of deformational auricular anomalies. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 62: 876-83.

- Byrd HS, Langevin C-J, Ghidoni LA (2010) Ear molding in newborn infants with auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 126: 1191-1200.

- Kim M, Lee H-M, Choi S-W, Lee S, Kim C (2021) et al. A longitudinal study of changes of congenital auricular deformity regarding selfcorrection. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 74: 2705-2711.

- Zhao H, Ma L, Qi X, Qin J, Yin B (2017) et al. A Morphometric Study of the Newborn Ear and an Analysis of Factors Related to Congenital Auricular Deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 140: 147-155.

- Tan ST., Shibu M., Gault DT (1994) A splint for correction of congenital ear deformities. Br J Plast Surg 47: 575-578.

- Bradbury ET, Hewison J, Timmons MJ (1992) Psychological and social outcome of prominent ear correction in children. Br J Plast Surg 45: 97-100.

- Ullmann Y, Blazer S, Ramon Y, Blumenfeld I, Peled IJ (2002) Early nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 109: 907-913.

- Limandjaja GC, Breugem CC, Mink van der Molen AB, Kon M (2009) Complications of otoplasty: a literature review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 62: 19-27.

- Matsuo K, Hirose T, Tomono T, Iwasawa M, Katohda S (1984) et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in the early neonate: A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg 73: 38-51.

- Chang CS, Bartlett SP (2017) A Simplified Nonsurgical Method for the Correction of Neonatal Deformational Auricular Anomalies. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 56: 132-139.

- Zhao H., Lin G., Seong YH., Shi J., Xu J (2019) et al.Anthropometric research of congenital auricular deformities for newborns. J Matern Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet 32: 1176-1183.

- Chan SLS, Lim GJS, Por YC, Chiang MF, Ho S (2019) et al. Efficacy of Ear Molding in Infants using the EarWell Infant Correction System and Factors Affecting Outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg 144: 648e-658e.

- Zhong Z, Zhang J, Xiao S, Liu Y, Zhang Y (2021) Long-Term Effectiveness of Ear Molding in Infants Using the EarWell Infant Correction System in China. Plast Reconstr Surg 148: 616-623.

- Doft MA, Goodkind AB, Diamond S, DiPace JI, Kacker A (2015) et al.The newborn butterfly project: a shortened treatment protocol for ear molding. Plast Reconstr Surg 135: 577e-583e.

- Tan S, Wright A, Hemphill A, Ashton K, Evans J (2003) Correction of deformational auricular anomalies by moulding: Results of a fast-track service. N Z Med J 116: U584.

- Dinis J, Junn A, Long A, Phillips S, Reategui A (2022) et al. Non-Surgical Correction of Congenital Ear Anomalies: A Critical Assessment of Caretaker Burdens and Aesthetic Outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg 46: 898-906.

- Nigam M, Kotha VS, Barra C, Baker SB (2020) Nonoperative Molding of Congenital Ear Deformities: The Impact of Birth-Initiation Delay on Correction Outcome. J Craniofac Surg 31: 1588-1592.

- Yotsuyanagi T. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in children older than early neonates. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004 : 114:190–1. Doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000128819.03187.5D.

- Zhuang Q, Wei N, Zhou Q, Wang H, Wu Y (2020 ) et al. Efficacy and Timing of Neonatal Ear Correction Molding. Aesthetic Plast Surg 44: 872-878.

- van Wijk MP, Breugem CC, Kon M (2009) Non-surgical correction of congenital deformities of the auricle: A systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 62: 727-736.

- Chang CS, Bartlett SP (2019) Deformations of the Ear and Their Nonsurgical Correction. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 58: 798-805.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.