Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Repair of a Right-Sided Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia: A Case Report

by Liv Faulhaber, Maximilian Bockhorn, Fadl Alfarawan*

University Clinic for General and Visceral Surgery, Oldenburg, Germany

*Corresponding author: Fadl Alfarawan, University Clinic for General and Visceral Surgery, Oldenburg, Germany

Received Date: 03 March 2025

Accepted Date: 06 March 2025

Published Date: 10 March 2025

Citation: Faulhaber L, Bockhorn M, Alfarawan F (2025) Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Repair of a Right-Sided Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 10: 2209. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102209

Abstract

Background: Approximately 5% of all patients hospitalized after a car crash suffer from a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia (TDH). Surgery is the treatment of choice in patients with TDH. However, there is no gold standard with regard to the surgical method. In literature there are both recommendations of an open approach (laparotomic or thoracotomic), and recommendations of a minimal invasive approach (laparoscopic or thoracoscopic). Although robotic surgery has gained importance there are only few reports of robotic surgery used in the repair of complicated diaphragmatic hernia (DH)

Case presentation: We present a 62-year-old male patient with a traumatic TDH who presented to our emergency department with an incarceration of the right liver lobe, the transverse colon and stomach. In 2017 the patient had a car accident. However, the diagnosis of TDH had been missed for 7 years in spite of multiple CT and MRI scans. Emergency operation was performed transabdominally assisted by the da Vinci System X. The defect was easily repaired with a PDS 0 in continuous suture technique. For further stabilization a 15x15cm IPOM mesh was placed on the repaired defect. Throughout the procedure the robotic arms could reach easily into the right hemithorax for reduction of the hernia contents. The postoperative stay in hospital presented uneventful, the patient was discharged on day 4. On a routine 30-day check-up the gentleman was symptom free.

Conclusion: To put it in a nutshell, we are convinced that a robotic transabdominal approach is the technique of choice in TDH. Robotic repair provides greater visualization than laparoscopy and suturing the defect can be achieved with ease due to the articulating arms of the robot.

(271 word)

Keywords: TDH (Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia); Robotic surgery; IPOM (intraperitoneal mesh augmentation).

Abbreviations: CT: Computer Tomography; DH: Diaphragmatic Hernia; IPOM: Intraperitoneal Mesh Augmentation; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; TDH: Traumatic Diaphragmatic Hernia.

Introduction

A traumatic diaphragmatic hernia (TDH) is defined as the incursion of intraperitoneal structures into the thorax after a traumatic event [1]. TDH may occur as a consequence of either direct trauma causing a penetrating injury to the diaphragm or indirectly by a sudden increase in intraabdominal pressure [2, 3]. The most common cause of a TDH due to blunt trauma are car crashes [3]. Approximately 5% of all patients hospitalized after a car crash suffer from a TDH [4]. Herniation through the left side of the diaphragm is more common and is recorded in up to 80% of TDH [5]. Different organs may herniate into the thorax depending on the location and defect size of the TDH: In case of a large defect more than one organ may herniate into the thorax [6]. TDH may be associated with other sever injuries like for example splenic rupture. However, patients are frequently asymptomatic and thus diagnosis may be delayed [5]. Carter et al. describe three different phases of TDH: acute phase, latent phase, and obstructive phase [7]. During the acute phase, up to 66% of TDH are overlooked [3]. The latent phase is defined by unspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a reduction in respiratory function. Symptoms may be present infrequently [3, 6]. In the course of time, the size of the defect in the diaphragm usually increases resulting consequently an increase in symptoms [8]. If TDH stays undetected the latent phase can be followed by the so-called obstructive phase. This phase is characterized by incarceration of visceral organs with resulting necroses and subsequent sepsis [3, 6]. In a cohort of paediatric patients delayed diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture was associated with right sided defects [9].

In patients with TDH imaging plays a key role. X-ray is often the starting point of the diagnostic work up [10]. However, the sensitivity of X-ray imaging is low, only 17-33% of right sided hernias are detected [11]. Hence, the gold standard instrument to diagnose TDH is the CT-scan. The location, size and content of the hernia can be accurately described [3,5].

Surgery is the treatment of choice in diaphragmatic hernia. In literature there is a consensus that the diaphragmatic defect should be closed by non-absorbable suture, for large defects a mesh augmentation can be applied [5]. However, a variety of approaches has been described in literature. In literature there are both recommendations of an open approach (laparotomic or thoracotomic), and recommendations of a minimal invasive approach (laparoscopic or thoracoscopic) [3,5,6,12]. Although robotic surgery has gained importance there are only few reports of robotic surgery used in the repair of complicated diaphragmatic hernia (DH) [12-14]. Lima et al. and Hunter et al. describe a robot-assisted thoracoscopic approach [12,14]. In contrast, Jambehkar et al. describe a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach [13].

We present a very rare case of a 62-year-old male patient with a right sided TDH who underwent successful robotic-assisted laparoscopic mesh augmented repair.

Case Report

A 62-year-old male presented to our emergency department in late September 2024 with nausea and vomiting over the last few hours. His vital signs were stable and on examination, the abdomen was distended with epigastric tenderness.

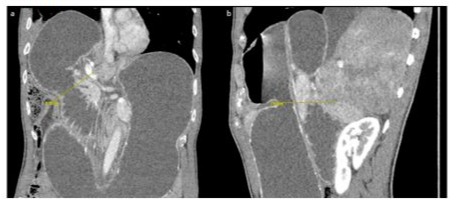

Summarizing the patient history, one has to know that in 2017 the patient had a car accident. On admission a CT-Scan of the thorax and abdominal cavity was carried out. Apart from a pelvic ring fracture (Type B3.3.C) no other pathologies were described. Osteosynthesis was performed. The postoperative stay in hospital was uneventful. Over the following years the patient frequently visited a lung specialist due to dyspnea. In 2019 an MRI of the upper abdomen was conducted due to elevated liver enzymes in the blood work up. However, the diagnosis of TDH war missed. In early September 2024 the patient presented to our emergency department due to unspecific abdominal pain. The then conducted CT-scan showed a right-sided TDH with herniation of the right liver lobe, stomach and colon (Figure 1A,1B). There were no signs of incarceration. Under conservative treatment the symptoms were manageable, and the patient was dismissed with an appointment for robotic-assisted repair. However, in late September a few weeks before the planned procedure - the latent phase of TDH had expired and the obstructive phase had begun, thus emergency surgery had to be performed.

Figure 1: A, B: CT abdomen with Incarcerated right-sided diaphragmatic hernia. Here, the incarcerated right liver lobe, right colon, pylorus, duodenum, and gallbladder can be seen, resulting in a high-grade ileus.

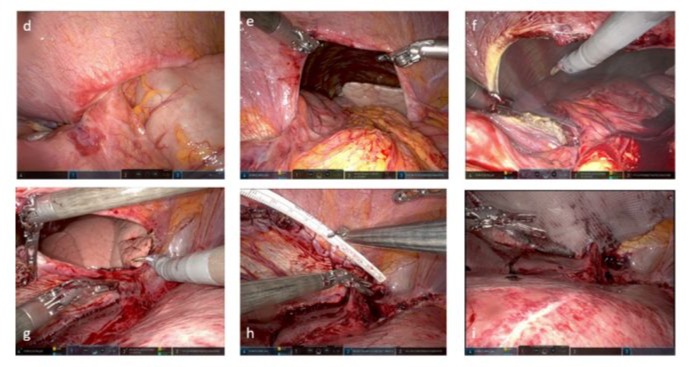

In the operating theatre the patient was placed in the left-lateral decubitus position, with the right arm extended low and above the head on a standard arm board. A small amount of reverse Trendelenburg positioning was applied. We used the five-port technique for surgery: one 10-mm assistant port above the umbilicus and four 8-mm ports for the robotic arms. The robotic ports were placed below the right costal margin approximately 6-cm apart (Figure 1C). The patient cart of the DaVinci System X was placed at a 45° angle over the patient’s right shoulder. The inspection of the abdominal cavity showed a large TDH with herniation of the right liver lobe, the distal part of the stomach and the right colonic flexure in the thorax (Figure 1D). The herniated colon and stomach were reduced easily from the right hemithorax. However, the right liver lobe was incarcerated (Figure 1E,1F), the diaphragmatic defect had to be widened by a few centimetres. The original defect measured 8 x 7cm (Figure 1G). The reduction of the right liver lobe was then performed. After placing a 24 Char. chest tube under direct visualization the diaphragmatic defect war repaired with a PDS 0 in continuous suture technique (Figure 1H). Due to the defect size we then placed a 15x15cm IPOM mesh on the repaired defect (Figure 1I).

Figure 1C: Positioning of the patient in an extended left lateral decubitus position and Anti-Trendelenburg. Port placement along the costal arch.

Figure 1D: Incarcerated right-sided diaphragmatic hernia. 1E: Repositioning of the colon, duodenum, and stomach. 1F: Enlargement of the hernia to allow liver repositioning. 1G: Repositioning of the liver and visualization of the hernia. 1H: Closure of the hernia. 1I: reinforce me with Ventralight mesh (15x15 cm).

Throughout the procedure the robotic arms could reach easily into the right hemithorax for reduction of the hernia contents. The DaVinci allows smooth preparation with minimal traumatic handling of the tissue.

The postoperative stay in hospital presented uneventful, the chest tube and the abdominal tube could be removed in a timely manner. The postoperative final chest X-ray demonstrated no evidence of a remaining hernia (Figure J). Our patient was started on a fluid diet postoperatively, the step-by-step return to a normal diet was unproblematic and he was discharged on day 4 after an uneventful recovery. On a routine 30-day check-up in December 2024 the patient was symptom free and reported being back to the gym.

Figure 1J: Chest X-ray after removal of the thoracic drain on the 2nd postoperative day.

Discussion

Up to date no standard operating technique is recommended for the repair of TDH [13]. In the past a thoracotomy or a laparotomy was usually performed [15]. However, we are convinced that a robotic transabdominal approach is the technique of choice. Robotic repair provides greater visualization than laparoscopy. The transabdominal approach has no disadvantages with regard to deep dissection into the thoracic cavity compared to the transthoracic approach reported by Hunter et al. [14]. On top of that, suturing the defect can be achieved with ease due to the articulating arms of the robot. Based on our case we are convinced that robotic repair is feasible, safe, and thus superior to laparoscopy or laparotomy. However further studies are needed to decide on the gold standard for TDH repair.

References

- Blitz, M. and Louie, B.E. (2009) Chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Thoracic surgery clinics, 19: 491–500.

- COOLEY, J.C. and ROGERS, J.C. (1959) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill: 1960), 79: 581–587.

- Giuffrida, M, Perrone, G, Abu-Zidan, F, Agnoletti, V, Ansaloni, L, et al (2023) Management of complicated diaphragmatic hernia in the acute setting: a WSES position paper. World journal of emergency surgery: WJES, 18: 43.

- Meyers, B.F. and McCabe, C.J. (1993) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Occult marker of serious injury. Annals of surgery, 218: 783–790.

- Testini, M, Girardi, A, Isernia, R.M, Palma, A. de, Catalano, G, et al (2017) Emergency surgery due to diaphragmatic hernia: case series and review. World journal of emergency surgery: WJES, 12: 23.

- Filosso, P.L, Guerrera, F, Sandri, A, Lausi, P.O, Lyberis, P, et al (2019) Surgical management of chronic diaphragmatic hernias. Journal of thoracic disease, 11: S177-S185.

- carter, B.N, Giuseffi, J, Felson, B. (1951) Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. The American journal of roentgenology and radium therapy, 65: 56–72.

- Basol, O. and Bilge, H. (2022) Our surgical experience in traumatic and congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Single-center study. Nigerian journal of clinical practice, 25: 391–394.

- Wu, C.-T, Huang, J.-L, Hsia, S.-H, Lin, J.-J, Lai, S.-H. (2009) Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in pediatric emergency room: two case reports. European journal of pediatrics, 168:1013–1015.

- Lomoschitz, F.M, Eisenhuber, E, Linnau, K.F, Peloschek, P, Schoder, M, et al (2003) Imaging of chest trauma: radiological patterns of injury and diagnostic algorithms. European journal of radiology, 48: 61–70.

- Sangster, G, Ventura, V.P, Carbo, A, Gates, T, Garayburu, J, et al (2007) Diaphragmatic rupture: a frequently missed injury in blunt thoracoabdominal trauma patients. Emergency radiology, 13: 225–230.

- Lima, M, Di Salvo, N, Ugolini, S, Libri, M, Ruggeri, G. (2018) Robot-assisted thoracoscopic repair of a late-onset Bochdalek hernia: a case report. La Pediatria medica e chirurgica: Medical and surgical pediatrics, 40.

- Jambhekar, A, Robinson, S, Housman, B, Nguyen, J, Gu, K, et al (2018) Robotic repair of a right-sided Bochdalek hernia: a case report and literature review. Journal of robotic surgery, 12: 351–355.

- Hunter, L.M, Mozer, A.B, Anciano, C.J, Oliver, A.L, Iannettoni, M.D, et al (2019) Robotic-Assisted Thoracoscopic Repair of Right-Sided Bochdalek Hernia in Adults: A Two-Case Series. Innovations (Philadelphia, Pa.), 14:69–74.

- Kanazawa, A, Yoshioka, Y, Inoi, O, Murase, J, Kinoshita, H. (2002) Acute respiratory failure caused by an incarcerated right-sided adult bochdalek hernia: report of a case. Surgery today, 32: 812–815.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.