RNA Sequencing Yields Actionable Markers in a Rare Case of Pediatric Male Secretory Breast Carcinoma

by Sohini Guha1,2#, Somrita Das3#, Shashikumar T1,2, Kiruthiga Raghunathan1, Pragnya Coca4,5, Shobha Badiger4, Sujan K. Dhar1, Manjula Das1,3*

1Mazumdar Shaw Medical Foundation, Narayana Health City, Bangalore 560099, India.

2MAHE, Manipal, 576104, India.

3Centre for Precision Diagnostic and Therapeutic Research, India, Electronic City, Bangalore 560100, India.

4Mazumdar Shaw Medical Centre, Narayana Health City, Bangalore 560099, India.

5Manipal Hospitals, Kanakapura road, Bangalore 560062, India.

#These authors contributed equally to this work.

*Corresponding author: Manjula Das, Advanced Diagnostic Research Center (ADRC), Mazumdar Shaw Medical Foundation, Narayana Health City, Bangalore 560099 India.

Received Date: 17 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 05 January, 2026

Published Date: 07 January, 2026

Citation: Guha S, Das S, Shashikumar T, Raghunathan K, Coca P, et al. (2026) RNA Sequencing Yields Actionable Markers in a Rare Case of Pediatric Male Secretory Breast Carcinoma. J Oncol Res Ther 11:10323. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10323

Abstract

Male breast cancer constitutes to be <1% of all breast cancer cases with pediatric male secretory breast carcinoma (SBC) reported only in isolated case reports. SBC is typically triple-negative and indolent, driven by the characteristic ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. However, the molecular landscape of aggressive pediatric male SBC remains poorly understood. The objective of this study was to identify clinically actionable molecular alterations in the pediatric male SBC case using integrated next-generation sequencing (NGS). whole exome sequencing (WES) and transcriptome profiling using an Illumina platform were done on post-treatment retrospective samples from the fifth year of illness. Expression profiles were compared with HER2 -stratified male breast cancers from TCGA-BRCA cohort. Immune checkpoint and fusion interactome analyses were conducted to identify activated pathways. WES identified fifteen somatic exonic mutations, implicating pathways involved in metabolism, cell adhesion, signaling, and inflammatory responses, but were not actionable. On the other hand, transcriptomic profiling revealed appreciable expression of HER2, may be attributable to gemcitabine-induced NF-κB activation or initial false-negative IHC. Interestingly, fusion analysis of the transcriptome itself identified the canonical ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangement with validated breakpoints and evidence of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathway activation. In addition, high expression of secretory lineage genes (SCGB2A2, SCGB1D2) among many were noted. Hormone receptors (ESR1, PGR, AR) were negligible, whereas Immune checkpoint analysis showed elevated HMGB1, LAG3, LGALS9, PDL1, and CD86 expression. Thus, transcriptomic analysis uncovered multiple clinically actionable alterations in a rare pediatric male SBC. These findings demonstrate the diagnostic value of comprehensive and integrative genome-transcriptome analysis, especially in rare, aggressive tumours to guide precision oncology.

Keywords: Pediatric Male Breast Cancer; Secretory Breast Carcinoma; Transcriptome Analysis; Whole Exome Analysis; Precision Medicine;

Introduction

Male breast cancer accounts for < 1% of all breast cancer cases and 0.5% of all malignancies in men [1, 2]. This malignancy can originate from the epithelium of the ducts or lobules of the breast. Male breast cancer risk factors include family history, radiation exposure, estrogen therapy, hyper estrogenic states (cirrhosis, Klinefelter’s), and testicular disorders such as undescended testes, orchitis, and infertility [3]. Analysis of a large cohort (n = 2,696,734) indicated the age at diagnosis ranged from 47 to 77 years, with a mean age of 60 years [4, 5]. Primary breast cancer in the pediatric population is exceedingly rare, representing <0.1% of all breast cancers and <1% of all pediatric malignancies [6, 7]. While the vast majority of cases occur in females, male pediatric breast cancer is found in the literature primarily as isolated case reports. In a literature review of 32 cases (ages 4-17 years), 62.5% occurred in females and 37.5% in males [6]. Overall, pediatric male breast cancer remains an exceptional finding compared with the female counterpart.

Although the disease is rarer in the pediatric population, it appears to be more aggressive than in adults [8]. Secretory breast cancer (SBC) is a rare kind of breast cancer, accounting for 0.15% of all infiltrating breast cancers, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:31 according to National Cancer Database analysis [9]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), breast tumours are classified among exceptionally rare tumour types [10]. Secretory breast carcinoma (SBC) represents the most common breast cancer in children, yet it remains rare overall, comprising less than 1% of all childhood malignancies [11-14].

SBC is even rarer in males, with 15 reported cases until 2004 [15, 16]. Previous studies indicate that SBC is negative for estrogen receptor (ESR1), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2 or HER2), but positive for basalcell markers; therefore, it has been classified as a specific subtype of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). It is estimated that 10% of men with breast cancer have a genetic predisposition such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN, P53, CHEK21, androgen receptor (AR) gene mutations or CYP17 polymorphism [17]. Moreover, it has been reported that there is an increased risk of cancer in 5-10% of men who carry mutations in the tumour suppressor gene BRCA2 [18, 19].

In 2002, SBC was first reported to harbour the following recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation: t(12;15) (p13; q25). This translocation leads to the formation of the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion [20]. Pediatric SBC has been reported to have distinctive molecular features. In a previous study, a 6-year-old boy had a triple-negative tumour with basal and luminal markers, harbouring the classic t(12;15) fusion plus a 3q28 duplication (also present in his father and grandfather with prior breast cancer, but without BRCA mutations) [21]. Another case in a 5-year-old boy revealed an ETV6-NTRK3 translocation and a PDGFRB c.2632A>G mutation, but no alterations in BRCA1/2, TP53, RAD51C, or RAD51D [22]. Overall, such tumours exhibit a basal-like phenotype (CK5/6 or EGFR-positive), diffuse MUC4 expression, frequent SOX10 positivity, and are either triple-negative or weakly ER-positive [23].

Unlike basal/triple-negative breast cancers of no special type, secretory carcinomas exhibited an exceptionally low mutational burden, lacking pathogenic alterations in common cancer-related genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53, RAD51C, and RAD51D [20]. These findings highlight ETV6-NTRK3 as the principal oncogenic driver and explain the indolent clinical course of secretory carcinomas. In addition to genetic profiling, identification of mutations has become increasingly relevant in metastatic breast cancer, complementing traditional immunohistochemistry. Mutations of the catalytic subunit α of the PIK3CA gene, present in up to 40% of luminal tumours, provide eligibility for treatment with the PI3K inhibitor Alpelisib, while activating HER2 kinase domain mutations are potentially amenable to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as tucatinib and neratinib. Furthermore, ESR1 mutations contribute to endocrine resistance in a significant proportion of advanced luminal cancers, and NTRK gene fusions, detected in nearly 50% of secretory carcinomas, predict marked responsiveness to Larotrectinib. These findings underscore the growing clinical importance of predictive molecular pathology in guiding personalized therapy [24].

NTRK fusions, though uncommon, define a therapeutically relevant subset of breast cancers. In a cohort of 23 fusion-positive cases, 11 were secretory (7 with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion), 11 nonsecretory (7 with NTRK1) and 1 mixed, with secretory tumours occurring in younger, ER-negative patients and non-secretory tumours enriched for TP53 mutations [24]. Querying the TCGA Pan Cancer Atlas Breast Invasive Carcinoma cohort revealed that none of the 12 male breast cancer samples harboured the ETV6NTRK3 fusion, while only two female BRCA cases exhibited this rearrangement. These results, along with detection of gene-fusion from transcriptome data, establish that NTRK fusions extend beyond secretory breast cancer, highlighting the critical role of integrative genomic-transcriptome profiling in identifying patients eligible for TRK inhibitor therapy.

At present, surgery is considered the mainstay of treatment for SBC and can include wide local excision, simple mastectomy, and modified radical mastectomy. We present a rare pediatric male case of metastatic SBC with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion and post-treatment elevated HER2 expression, exploring the implications of precision oncology and the challenges associated with rare malignancies. Moreover, we highlight the role of comprehensive transcriptomic analysis to detect not only high expression of markers, but also gene-fusion, which classically is done by karyotyping, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or targeted qPCR.

Case Presentation

A less than 12-year-old male child from African countries presented with a right chest wall lesion. The case history stated that the lesion was first noticed at the age of 2 years, following which a fine needle aspiration (FNA) was performed, which was inconclusive. Over the next five years, the lesion gradually increased in size. At the age of 7, an excisional biopsy was done, following which the histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis as secretory breast carcinoma (SBC). 6 months into the post-operative period, multiple rapidly growing lumps appeared over the chest wall, for which a radical mastectomy with axillary clearance was performed. Lymph node involvement was found to be negative. He received 6 cycles of CMF chemotherapy (consisting of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil), the last dose of which was administered 2 months before presentation.

The child presented with a new chest wall nodule noticed 3 months prior to admission. On PET-CT scan, no other sites of disease were found. On reviewing the block sample obtained from the surgery done in his country, the presence of secretory breast carcinoma with DCIS was found. Margins were positive for tumour. Subsequently, an excisional biopsy of the nodule was done and diagnosed as metastatic secretory breast carcinoma. Immunohistochemical staining of the tumour cells demonstrated negativity for ESR1 (0/8), PR (0/8), and HER2 (0/8), whereas Ki-67 labelling index was approximately 10%. DNA and RNA were isolated from this biopsy sample for whole-exome and transcriptome sequencing. He also underwent germline testing at this stage, which showed

BRCA2 and MLH1 mutations. Postoperatively, he was also given 2 cycles of AC chemotherapy (consisting of Adriamycin and cyclophosphamide). He also received radiotherapy to the left chest wall for three months; however, due to logistics, the schedule was interrupted since he wanted to continue his treatment back home.

Three years after returning home, he developed metastases to the lung for which he was given three more cycles of AC chemotherapy in Africa. Subsequently, he was put on 3 cycles of chemotherapy consisting of Gemcitabine and Carboplatin. As the disease status remained stable, he was treated with oral tamoxifen for 3 months and then underwent one cycle of Cyclophosphamide, Etoposide, and Celecoxib at the discretion of the local treating oncologist in Africa, before being presented to the centre in India again after one year.

Repeat PET-CT scan showed multiple metastases. He was then started on oral Capecitabine for one year. He was reviewed then with a repeat PET-CT scan, which showed progressively increasing lung metastasis. Given a likely pathogenic BRCA2 mutation, options for poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors were suggested. The patient wished to continue therapy in his native country and defaulted on the suggested options. Eventually, he died in September 2024 at the age of 16 years.

Materials and Methods

RNA and DNA were isolated from the retrospective biopsy specimen using TRIzol reagent (#15,596,018; Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The air-dried pellet was then dissolved in nuclease-free water for further processing. For DNA isolation, genomic DNA was recovered from the interphase and organic phase of the same extraction, precipitated using ethanol, and washed before resuspension. RNA was quantified using Qubit RNA Assay BR (#Q10210; Invitrogen) for sequencing.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) isolated from the biopsy specimen was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X platform using 150 bp paired-end chemistry. Raw reads were quality-checked and filtered using fastp [25] and subsequently aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using the STAR aligner [26]. Gene expression was quantified as transcripts per million (TPM). Gene fusion detection was performed using the STAR-Fusion pipeline on aligned data. Candidate fusions were queried in fusion databases, including ChimerDB 4.0 and FusionGDB2, for validation and to determine their occurrence in published cancer cohorts. Wholeexome sequencing (WES) was performed on DNA derived from the same sample using the Illumina HiSeq X platform with 150 bp paired-end chemistry. Reads were aligned to GRCh38 using BWAMEM, and variant calling was performed using the GATK best practices pipeline. Identified variants were annotated using the COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.2.2). No formal statistical testing was performed, given the single-patient nature of this study.

Results

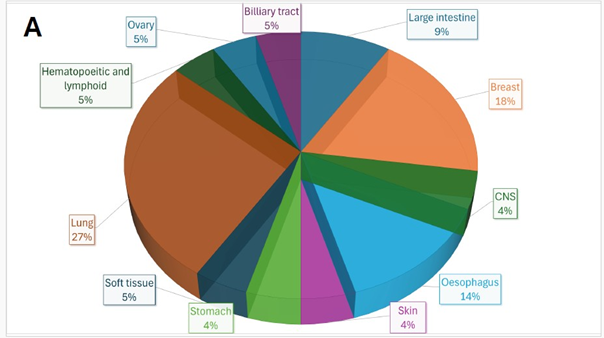

Mutational Analyses: Whole-exome sequencing identified 15 exonic somatic mutations with COSMIC annotations, including four recurrently reported in breast cancer: ACAD11, OR6A2, PTPRM, and INSR. Collectively, these genes implicate key oncogenic processes: metabolic rewiring (ACAD11), dysregulated cell signaling and adhesion (PTPRM, INSR), and emerging roles for ectopic GPCRs in tumour biology (OR6A2) while consistent with breast tumorigenesis, the broader set of variants was most frequently observed in lung cancers (27%) across COSMIC (Figure 1A), a finding of particular relevance given the lung’s status as a common metastatic site in breast cancer. This finding aligned with the clinical presentation of our patient, who developed lung metastases. This overlap highlights potential shared molecular vulnerabilities that may facilitate metastatic tropism to the lung, underscoring the biological relevance of the mutational landscape in this rare pediatric SBC case.

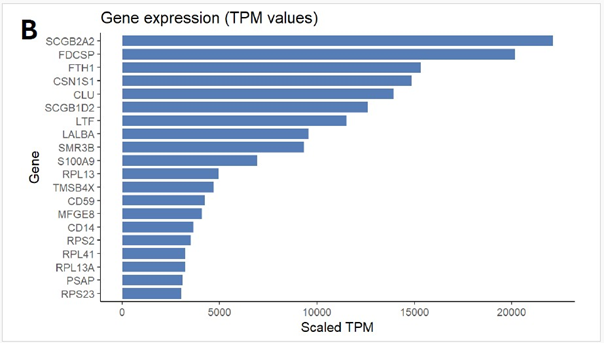

Pathway Analyses: Transcriptomic profiling of the tumour revealed that the most abundantly expressed genes were strongly enriched for secretory and epithelial lineage markers, including SCGB2A2 (mammaglobin-A), SCGB1D2, LTF, LALBA, and CSN1S1.

These findings further support the histopathological diagnosis of secretory breast carcinoma, reinforcing the tumour’s mammary epithelial origin despite its unusual clinical behaviour. In addition, highly expressed genes such as FTH1, CLU, and S100A9 are associated with cellular stress responses, iron metabolism, and inflammatory signaling, suggesting an adaptive or pro-tumorigenic microenvironment. The prominence of ribosomal (RPL13, RPS2, RPL41, RPL13A, RPS23) and cytoskeletal (TMSB4X) transcripts reflects the tumour’s high biosynthetic and proliferative activity. The expression landscape highlights the secretory differentiation program and the metabolic-inflammatory adaptations that may contribute to the tumour’s aggressive course. (Figure 1B)

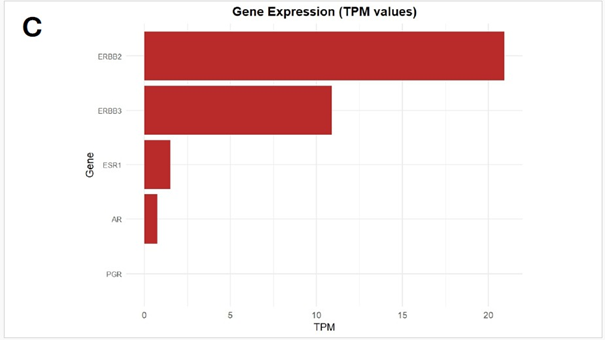

HER2 Expression: Furthermore, transcriptome analyses of the tumour revealed absent or negligible expression of canonical hormone receptor genes, including ESR1, PR and AR, based on scaled TPM values. In contrast, HER2 was expressed appreciably, suggesting a Ν-enriched molecular subtype. This expression profile indicates a hormone receptor-negative, HER2-positive tumour, uncommon in secretory breast carcinoma, typically characterized by a triple-negative, indolent phenotype. (Figure 1C)

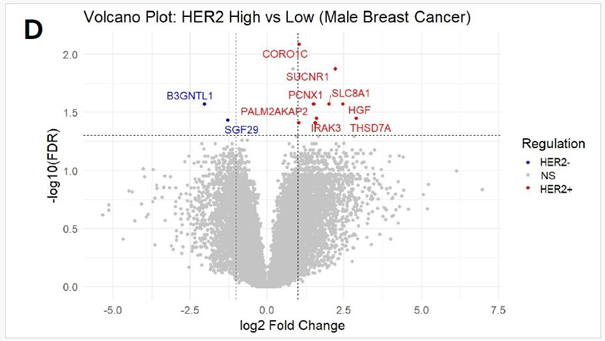

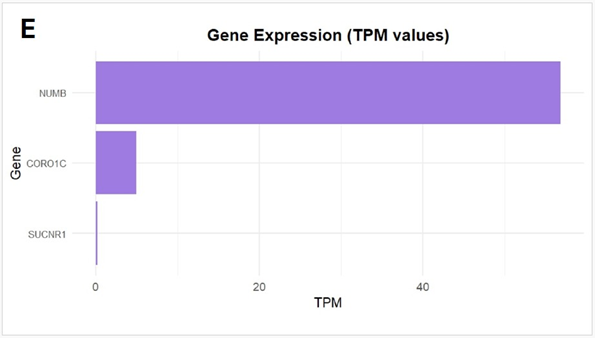

Differential gene expression analysis was performed using RNAseq data from 12 male patients from the TCGA-BRCA cohort, stratified into groups based on median HER2 expression levels to further contextualize the tumour’s transcriptomic profile. (Figure 1D). Analysis revealed that HER2-high tumours exhibited higher levels of genes THSD7A, HGF, SUCNR1, SLC8A1, IRAK3, ZNF521, PCNX1, PALM2-AKAP2, CORO1C, TTLL5 and NUMB compared to tumours in the lower half of HER2 expression. Functional enrichment of these elevated genes converged on negative regulation of protein phosphorylation, suggesting that, alongside HER2-driven hyperactive kinase signaling, a parallel regulatory program may emerge to buffer excessive phosphorylation. HGF and SUCNR1 indicate crosstalk between HER2 and growth factor/GPCR-mediated pathways within this network, whereas NUMB and IRAK3 suggest endocytosis and immune modulation regulatory circuits. On the other hand, the downregulated genes SGF29 and B3GNTL1 in HER2 -high tumours, which are chromatin-associated regulators, suggest the suppression of epigenetic modulators in the HER2 -high context. CORO1C and NUMB were also expressed in our patient, providing transcriptomic confirmation of a HER2-enriched subtype. This subtype, characterized by HER2 positivity in the absence of hormone receptor expression, is atypical and relatively uncommon in male breast cancer, where hormone receptorpositive phenotypes are more prevalent. (Figure 1E) Although SBC is typically triple-negative, our RNA-based findings suggest that HER2-targeted therapy may have therapeutic value even in the absence of HER2 protein overexpression.

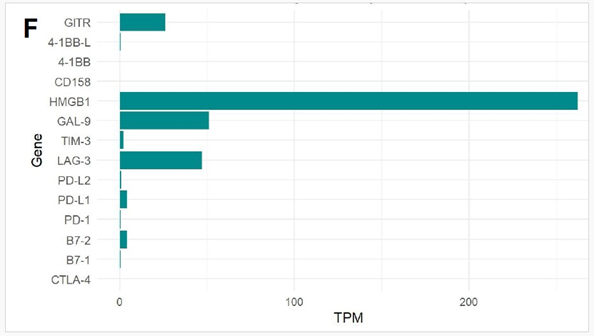

Expression of Immune Checkpoint Markers: Next, we evaluated the expression of immune checkpoint markers in the patient’s tumour transcriptome. Among the markers analyzed, HMGB1 showed the highest expression with a scaled TPM exceeding 250. Moderate expression levels were observed for LAG3 (~50 TPM), LGALS9/ Galectin-9 (~50 TPM), GITR, PD-L1 (CD274), and B7-2 (CD86). The presence of these molecules may reflect an immunologically active tumour microenvironment with potential immune evasion mechanisms and may have implications for responsiveness to immune checkpoint blockade therapies. (Figure 1F)

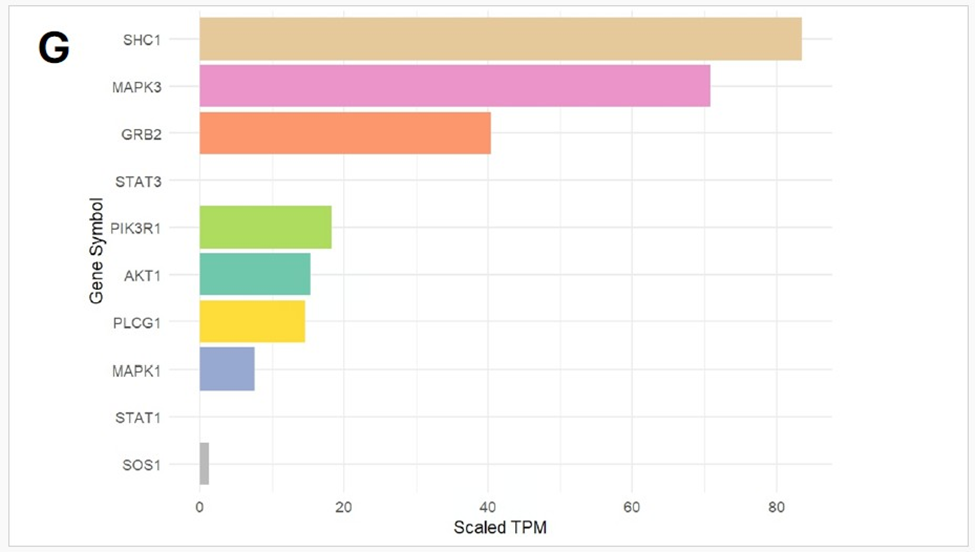

Detection of ETV6-NTRK3 fusion from Transcriptome analysis: STAR-Fusion detected multiple putative fusion events; among these, the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion exhibited the highest spanning fragment count (n = 10), strongly supporting its biological relevance, with the breakpoint mapped to exon 5 of ETV6 (chr12:11869969) and exon 15 of NTRK3 (chr15:87940753). This breakpoint combination corresponds to the canonical variant reported in secretory breast carcinoma (SBC) and other tumour types [27]. Further exploration of the fusion interactome revealed strong expression of key adaptor and signaling molecules, notably SHC1 and MAPK3, with moderate expression of PIK3R1, AKT1, PLCG1, and MAPK1. These findings suggest activation of the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, consistent with the known oncogenic signaling cascade downstream of the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion. (Figure 1G). When cross-referenced with ChimerDB 4.0 fusion database, ETV6-NTRK3 fusion with the exact breakpoints was observed in a subset of breast, colon, and skin tumours in the TCGA dataset.

Figure 1: (A) Distribution of 15 exonic mutations identified by WES across cancer types based on COSMIC data, and (B) Normalized TPM values of top 20 highly expressed genes in the patient’s tumour. (C) Expression levels (normalized TPM) of canonical hormone receptors (ESR1, PR, AR) and HER family receptors (ERBB2/HER2 and ERBB3), (D) Differentially expressed genes in TCGA-BRCA HER2-high and HER2-low MBC tumours (n = 12, stratified by median HER2 expression). (E)Expression of HER2-associated genes (CORO1C, NUMB, SUCNR1, among others), (F) Expression of selected immune checkpoint molecules (G) Expression levels of ETV6-NTRK3(e5-e15) variant interactome genes.

Discussion

The present work reports a rare case of pediatric male secretory breast carcinoma with triple-negative receptors and pathogenic BRCA2 and MLH1 mutations. Despite prior surgery and systemic therapies, the disease progressed. The transcriptome of stored posttreatment, fresh-frozen samples from fifth year of illness identified an actionable ETV6-NTRK3 fusion and Her2ν overexpression, indicating that the drug Gemcitabine induced overexpression of the markers.

This case emphasizes the utility of genomic and transcriptome analysis by next-generation sequencing in uncovering actionable molecular targets in rare and aggressive pediatric SBC. Early genomic and transcriptomic profiling could inform precision therapies such as HER2ν-directed or TRK inhibitor treatment, enabling tailored management and potentially improving outcomes in ultra-rare, treatment-resistant malignancies.

HER2 overexpression in a post-treatment sample, initially found to be triple negative, indicated therapy-induced upregulation of the marker. Gemcitabine is known to induce HER2 expression through NF-κB signaling [28]. However, methodological variability in IHC of the initial sample can also be a likely explanation. Unlike PD-L1 testing, which benefits from standardized antibody clones and validated scoring systems, HER2 IHC assays employ different antibody clones that target distinct epitopes. Therefore, a falsenegative IHC result can arise if the antibody fails to recognize the epitope expressed in the tumour. This underscores the importance of reflex testing, either by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing (NGS), in cases where HER2 IHC is negative or equivocal, typically scored as “2+” by the pathologist.

In this case of pediatric SBC, identifying key exonic mutations provided insights into the unusually aggressive clinical trajectory. While SBC is typically indolent, recurrent mutations observed in both breast and lung cancers, such as those affecting metabolic regulation (ACAD11), cell adhesion and signaling (PTPRM, INSR), and ectopic GPCR biology (OR6A2), raise the possibility that this tumour harboured molecular programs favouring metastatic dissemination. Notably, the lung was the site of metastasis in this patient, consistent with the overlap between the mutational landscape and lung cancer biology. This suggests that the mutational status may have contributed to the tumour’s adaptability, metastatic tropism, and treatment resistance.

Gene fusions are typically diagnosed by cytological methods like Karyotyping and/or FISH or targeted quantitative reversetranscriptase PCR. Though not a clinically popular method of detection, we reported in this work the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion by transcriptome analysis, done after the patient’s death, for research purposes. ETV6-NTRK3 is a well-established oncogenic driver in secretory breast carcinoma and a targetable alteration for which TRK inhibitors are available. [29] Early identification of the fusion at diagnosis could have enabled a precision-based intervention with an NTRK inhibitor. This case further highlights the systemic barriers faced in low- and middle-income countries, including limited access to advanced diagnostics, interruptions in therapy, and lack of easy availability of targeted drugs such as PARP inhibitors or TRK inhibitors. These challenges significantly delay or prevent the timely implementation of precision oncology in rare and aggressive forms of cancer.

Our findings emphasize a critical point: a single comprehensive NGS assay can often uncover multiple clinically relevant alterations, including HER2 expression at the transcript level, actionable exonic mutations, and structural variants, such as gene fusions, that conventional testing may miss. Earlier incorporation of transcriptome analysis by NGS into routine diagnostics could have expedited targeted therapy decisions and altered the clinical trajectory of this patient. We therefore advocate for the systematic integration of transcriptomic testing into the diagnostic and treatment pathway for rare and treatment-resistant cancers. This is the first report to integrate germline predisposition, transcriptomic receptor profiling, differential gene expression, immune checkpoint analysis, and fusion detection in a pediatric male secretory breast carcinoma. These molecular insights expand our understanding of this rare entity and highlight the transformative potential of precision oncology in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

PC and SB provided the samples and patient data for molecular diagnosis. ST and KG had performed the nucleic acid extraction and NGS library preparation, SG and SKD analyzed the NGS data, while SD and PC provided clinical interpretation. Manuscript was written by SD, SG, SKD and MD. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. The study was conceived and supervised by MD.

Ethical Statements

This study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained from the Narayana Health Academic Ethics Committee (Approval No: NHH/AECCL-2025-1484). The requirement for informed consent was waived, as the study involved retrospective analysis of anonymized patient data and archival tissue material.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study or its publication.

References

- Breast Cancer in Men (2021).

- Fentiman IS (2009) Male breast cancer: A review. Ecancermedicalscience 1:140.

- Elimimian E, Elson L, Li H, Liang H, Bilani N, et al. (2021) Male Breast Cancer: A Comparative Analysis from the National Cancer Database. World J Men’s Health 39:506-515.

- Salazar-Mejía C, Burguete-Torres A, González Guerrero J, VidalGutiérrez Ó, Wimer-Castillo B, et al. (2019) Breast cancer in men: 10-year experience of an Oncology Reference Centre in Northeast Mexico. The Breast 44: 21-25.

- Hassan N, Idaewor P, Rasheed N, Saad Abdalla Al-Zawi A, et al. (2023) Paediatric and Adolescent Breast Cancer: A Narrative Review. Cureus 15:e48983.

- Chung EM, Cube R, Hall GJ, González C, Stocker JT, et al. (2009) Pediatric and Adolescent Breast Masses: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation with Practical Clinical Applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 193: W101-W110.

- Dewi PAK, Raditha IN. (2021) A case report of male breast cancer in a 14-year-old patient. Int J Res Med Sci 9 :3451-3.

- Min N, Zhu J, Liu M, Li X. (2022) Advancement of secretory breast carcinoma: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med 10:1178-1178.

- Sinn HP, Kreipe H. (2013) A Brief Overview of the WHO Classification of Breast Tumours, 4th Edition, Focusing on Issues and Updates from the 3rd Edition. Breast Care (Basel) 8:149-54.

- Lombardi A, Maggi S, Bersigotti L, Lazzarin G, Nuccetelli E, et al. (2013) Amanti, Secretory breast cancer. Case report, G Chir 34: 125127.

- Cabello C, Alvarenga M, Alvarenga CA, Duarte GM, Pereira PN, et al. (2012) Case report and review of the literature: secretory breast cancer in a 13-year-old boy, 10 years of follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133: 813-820.

- Szántó J, András C, Tsakiris J, Gomba S, Szentirmay Z, et al. (2024 Secretory breast cancer in a 7.5-year-old boy, Breast 13: 439-442.

- Weiss JR, Moysich KB, Swede H (2005) Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14 :20-26.

- Ravi A, Bang H, Karsif K, Nori D. (2012) Breast cancer in men: prognostic factors, treatment patterns, and outcome. Am J Mens Health 6 :51-8.

- Zettira E, Hanriko R, Gigih S (2017) Breast Cancer in Men. Majority 7: 54-57.

- Brandt SM, Swistel AJ, Rosen PP, (2009) Secretory carcinoma in the axilla: probable origin from axillary skin appendage glands in a young girl. Am J Surg Pathol 33: 950-953.

- Kavalakat AJ, Covilakam RK, Culas TB, (2004) Secretory carcinoma of breast in a 17-year-old male. World J Surg Oncol 2: 2-17.

- Novochadlo Klüppel E, Rodrigues da Costa L, Marquetto Tognolo C, do Nascimento A, Grignet Ribeiro M, et al. (2020) Secretory breast carcinoma in a male child: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 73 :310-314.

- Li D, Xiao X,Yang W, Shui R,Tu X, et al. (2012) (Secretory breast carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunophenotypic study of 15 cases with a review of the literature. Mod Pathol 25: 567-575.

- Tognon C, Knezevich SR, Huntsman D, Roskelley CD, Melnyk N, et al. (2002) Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2 :367-76.

- Ghilli M, Mariniello MD, Scatena C, Dosa L, Traficante G, et al. (2018) Male secretory breast cancer: case in a 6-year-old boy with a peculiar gene duplication and review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 170: 445-454.

- Deng L, Li Y, Zhong J. (2023) Secretory breast cancer in a boy: A case report with genetic analysis using next-generation sequencing and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 102: e34192.

- Krings G, Joseph NM, Bean GR, Solomon D, Onodera C, et al. (2017) Genomic profiling of breast secretory carcinomas reveals distinct genetics from other breast cancers and similarity to mammary analog secretory carcinomas. Mod Pathol 30:1086-1099.

- Maund SL, Sokol ES, Ang Houle A, Ross JS, Wilson TR, et al. (2022) NTRK gene fusions are detected in both secretory and non-secretory breast cancers. Pathol Int 72:187-192.

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. (2018) Fastp: An Ultra-fast All-in-one FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 3: i884-i890.

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, et al. (2013) “STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-seq Aligner.” Bioinformatics 15-21.

- Wagner F, Greim R, Krebs K, Luebben F, Dimmler A, et al. (2021) Characterisation of an ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangement with unusual, but highly significant FISH signal pattern in a secretory carcinoma of the salivary gland: a case report. Diagnostic pathology 16- 73.

- Kan S, Koido S, Okamoto M, Hayashi K, Ito M, et al. (2015) Gemcitabine treatment enhances HER2 expression in low HER2expressing breast cancer cells and enhances the antitumor effects of trastuzumab emtansine. Oncology reports 34: 504-510.

- Kinnunen M, Liu X, Niemelä E, Öhman T, Gawriyski L, et al. (2023) The Impact of ETV6-NTRK3 Oncogenic Gene Fusions on Molecular and Signaling Pathway Alterations. Cancers 15: 4246.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.