Rheumatologic and Immunologic Manifestations of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: A Special Case Description and Literature Review

by Mohammad Adawi1*, Yousef Awni2, Adawi Ahlam3

1Department of Medicine, Baruch Padeh Medical Center, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel.

2Clalit General health, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel.

3Rabin MC, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

*Corresponding Author: Mohammad Adawi, Department of Medicine, Baruch Padeh Medical Center, Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel.

Keywords: Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis; Systemic Immunosuppression; Polyarthritis; Keratinolytics; Desmoplakins.

Received Date: 11 June 2025

Accepted Date: 16 June 2025

Published Date: 18 June 2025

Citation: Adawi M, Awni Y, Ahlam A (2025) Rheumatologic and Immunologic Manifestations of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis: A Special Case Description and Literature Review. 10: 2322. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102322

Abstract

We present a 57-year-old male with a lifelong history of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis (EH) who developed severe symmetrical polyarthritis with deformities resembling Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Methotrexate therapy yielded significant improvement in both articular and cutaneous manifestations. This case highlights the rare association between EH and inflammatory arthritis and underscores the potential role of systemic immunosuppression in managing such patients. Discussion: While EH primarily affects the skin, this case illustrates a rare inflammatory arthritis phenotype mimicking seronegative RA. The robust response to methotrexate suggests shared inflammatory pathways (e.g., IL-17/IL-23 upregulation in EH and psoriatic arthritis). Further studies are needed to explore this association. Conclusion: Methotrexate may be effective for EH-associated polyarthritis. Early rheumatologic referral is recommended for EH patients with articular symptoms.

Introduction

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is an uncommon keratinization disorder characterized histopathologically by loss of keratinocyte cell integrity and abnormal keratin deposition in the form of keratin aggregates in the suprabasal cell layers of the epidermis. Clinically, several variants of the disease exist based on the distribution and morphology of skin lesions. EHK manifests in a generalized lamellar variant in the neonate, whereas in the more common adult-onset localized variant, only the palms and soles exhibit epidermolytic changes, with lesions localized to glabrous skin [1]. In young women, EHK can occur in the vaginal mucosa, but only in a few localized case reports and an anecdotal fashion. Cutaneous erosions and constant burning sensation make the condition particularly distressing. EHK presents a challenge to treatment and indurated hyperkeratotic plaques on the vulvar area can be very difficult to treat. Elimination of luminal irritants, topical keratinolytics in combination with topical corticosteroids, and at times topical retinoids has been described in managing vulval EHK. Histopathology revealed a thickened, undulate epidermis with marked keratinocyte vacuolization in the suprabasal cell layers. Thick, dense keratin aggregates filled the featherylooking pseudo-epidermal cysts. Immunofluorescence-staining for intracellular junctions showed a marked reduction in desmoplakin stain and almost absent plakoglobin stain in the lesions [2].

Case Presentation

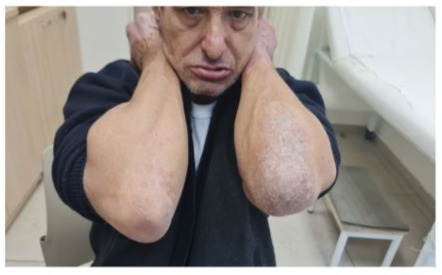

A 57-year-old man with genetically confirmed epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (onset in infancy) presented with progressive polyarticular pain, morning stiffness (>2 hours), and functional impairment in his hands and feet. Cutaneous examination revealed thickened, hyperkeratotic plaques and verrucous lesions on the palms and soles (Figure 1,2). Musculoskeletal evaluation demonstrated bilateral synovitis, ulnar deviation, and deformities of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, alongside similar involvement of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints.

Figure 1

Figures 1 and 2: Cutaneous examination revealed thickened, hyperkeratotic plaques and verrucous lesions on the palms and soles.

Laboratory tests: Elevated CRP/ESR; negative rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-CCP antibodies.

Imaging: X-rays showed periarticular erosions and joint space narrowing (hands/feet) without classic RA osteopenia.

Histopathology: Skin biopsy confirmed EH; synovial biopsy excluded granulomatous disease.

Treatment & Outcomes: The patient was initiated on methotrexate (15 mg/week) with folate supplementation.

Over 6 months, he reported: Marked reduction in joint pain/swelling (DAS-28 score improved from 5.2 to 2.1), Decreased morning stiffness (<30 minutes), Paradoxical improvement in hyperkeratotic lesions (Figure 3,4).

Figure 3

Figures 3 and 4: Decreased morning stiffness, Paradoxical improvement in hyperkeratotic lesions.

Overview of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is a rare disorder of keratinization that occurs due to mutations in the keratin genes (KRT1 and KRT10) in a developmental mechanism that is incompletely understood [2]. Previously referred to as epidermolytic ichthyosis, EHK is characterized by thickened and scaly skin, predominantly affecting high-friction areas of the body, including palms and soles. Other diagnostic features include an increase in the number of abnormal keratinocytes and parakeratosis. Cases of isolated EHK are both clinically and histologically differentiated from ichthyosis vulgaris, which is characterized more by increases in amounts of non-lamellar (type I) keratin (KRT9) within normal keratinocytes. Several genetic and environmental factors modulating keratinocyte biosynthesis, concentration, and arrangement of structural keratin can lead to hyperkeratosis. Patients with inherited epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EI) associated with KRT1 mutations develop extremely hyperkeratotic skin in infancy. Although newborns present with epidermolysis, over the following months, their skin grows increasingly more keratotic with extensive palmoplantar thickening. They continue to show blistering in early infancy, prompting performance of healing control/removal biopsies. Biopsy sections now reveal typical epidermolytic changes and hyperkeratosis with an increase in cornified cell layers and cytolysis, which can result in alopecia and hyperhidrosis. EI is less common than EI due to KRT10 mutations. The KRT1-associated forms include a severe congenital presentation characterized by blistering and an early onset, localized, and less severe phenotype. A unique N188H mutation in KRT1 may alter keratinocyte cell– cell adhesion, thereby leading to an increased susceptibility of keratinocytes to epidermolytic changes in this unique EI subset. Although no epidermolytic changes were visible in the biopsy obtained perinatally, a biopsy obtained in early infancy revealed vacuolar degeneration of the upper epidermal layers, and such histopathological changes spread in more distal sections of the skin over time to involve the trunk and limbs. Six patients with a novel KRT1 mutation (N188H) underwent clinical, genetic, transcriptomic, histological, and transmission electron microscopy analyses.

Genetic Basis of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EH) belongs to the ichthyosis group of keratinization disorders, a heterogeneous group of skin conditions that can be classified depending on the inheritance pattern, the affected layers of the skin barrier (i.e. epidermis, dermis, and/or follicle), and the mode of keratinization disturbance [3]. The most heavily studied forms of ichthyosis are the disorders of the epidermis, or non-syndromic ichthyosis. These can be further categorized depending on whether they are associated with a loss-of-function mutation in a specific epidermal gene, such as KRT1, 10, 14, 17, 9, FLG, or ALOXE3, or as a gain-of-function effect on a gene, such as KRT2E, or where the pathogenic variant has not yet been identified [2]. The keratins are a multigene family encoding over 50 different polypeptides which can be further grouped according to the size (i.e. acidic vs. basic) and solubility of the keratin filaments they produce (i.e. cytokeratin vs. hair keratin). Pathogenic variants in the keratin genes most commonly associated with ichthyosis are in KRT1, KRT10, KRT14 and KRT17. Since keratin filaments are crucial components of the cytoskeletal system, which governs mechanical properties both at the cellular and the cellular-epithelial levels, dysfunction of the keratin genes gives rise to mechanical instability; they can be seen as ‘stress absorbers’ of the epidermis. Recessive genotypes are associated with fragility at the outer-most level of the epidermis, leading to blistering. Dominant genotypes instead lead to aberrant keratin filament assembly in the lower epidermis. There are many examples of inherited skin diseases (mutations in KRT1, KRT10, KRT14, KRT17) where rigidity at the cellular-epithelial level leads to pronounced hyperkeratosis.

Pathophysiology of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EH) is often caused by a mutation in the KRT1 or KRT10 gene, resulting in a disruption of the intermediate filament network in the keratinocytes of the epidermis. Mutations in the KRT1 and KRT10 gene cause both dominant and sporadic mutations, resulting in autosomal dominant epidermolytic ichthyosis or EH. Most of these mutations lead to a nucleotide substitution resulting in single amino acid changes in the keratin proteins. The reported KRT1 alterations are at positions 2, 14, 40, 41, 58, 92, 96, 97, 98, 117, 118, 119, 139, 188, 196, 197, 198, 199, 226, 227, 233, 264, 272, 275, 280, 286, and 288. Genes in which mutations have previously been reported are indicated in bold, those newly reported in this paper in regular type, and the basal keratin genes that are not currently believed to be involved in EH are shown in italics. Approximately one half of all cases appear to occur sporadically at conception and be the result of a new mutation [2]. Often, the parents of these infants would be unaffected but show a normal mutation spectrum such that it is believed the EA and EH mutations may be the first two genes leading to subsequent abnormalities of both filaggrin keratin and loricrin leading to a more proliferative epidermal change. EH may also be a cause for facial involvement including the forehead, eyes, mouth, nose, forehead-bridge, and chin. Previously reported variants include duplications, deletions, and complex rearrangements, often involving either, ascention, or mutation at or near the start codon. An example of KRT1 deletion is shown with an arrow. The deleted fragment overlaps with EGF-1 and EGF-3.

Clinical Features

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is a rare and underreported epidermal disease associated with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis, often leading to prominent plaque-like ridges on both the ventral and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet [1]. EHK is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis, intercellular vacuolation, and keratinocyte necrosis [2]. The abnormal keratinization among the most superficial layers of the epidermis leads to trans-stratum corneum water loss, skin dryness, and barrier impairment; thus, predisposing to secondary inflammatory skin diseases. Patients with EHK often present with localized ichthyosis in the flexural areas of the knees and elbows, which may be associated with larger lesions and scarring of natal cleft and nail fold. Lesional skin shows multiple hyperkeratotic plaques, which may resemble craquelé or lamellar ichthyoses. The skin of the palms and soles exhibits pronounced keratoderma with prominent finger- and toeprints. Affected skin is usually dry with an abnormal appearance and scaling, itches, and fissures, but is not tender or red. Plaques are pink or skin-colored. In the hands and feet, they become thickened, at times displaying superficial fissuring. Occasionally, genitals are involved. Ocular, mucosal, and other systemic involvement has not yet been reported in EHK. Most patients appear to be well and follow a relatively benign course. There are no reports of other skin conditions unattached to EHK suggesting a distinct disease. Itching and fissuring can be significant. Topical emollients with or without salicylic acid or topical keratolytics effectively control predominant symptoms.

Skin Manifestations

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is a rare, inherited disorder of keratinization characterized by exuberant, hyperproliferative, and hyperkeratotic epidermis. EHK, also known as ichthyosis bullosa, is a disorder of premature keratinization [2]. EHK can occur as a part of a mosaic pattern or in nonmosaic forms. The latter is visible at birth or early childhood and can be divided into generalized, localized, and rarer presentation such as palmoplantar or vulvar involvement [1]. EHK carries a frequent association of nail dystrophy as well. The mechanistic basis of this condition relies on mutations in keratin 1 (KRT1), involved in the formation of the filamentous cytoskeleton of the epidermis and its appendages, or keratin 10 (KRT101). Mutations in other keratins such as KRT9, KRT14, KRT15, keratin associated protein 1 and 12 (LOR, KRTAP1-12) can also cause clinically similar but rare variants. Mutations in the genes coding for desmosomal cadherins, for example, mutation in DSG1 and desmoplakins (DSP) can cause a rare form of EHK. Mutations in other genes, for instance, in loricrin (LOR) have been implicated in EHK as well.

Systemic Symptoms

Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis is a rare disorder of keratinization due to mutations in keratin genes 1 or 10. These mutations lead to defective keratin filaments and damaged keratinocytes which are frequently found in the epidermis of patients with EHK along with other microscopic findings including loss of normal intercellular junctions, secretion of abnormal keratins, grain degeneration of filaments and cytoplasmic keratin aggregation. Mutation resulting Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis ectodermal dysplasia is filed under keratin 1 abnormality. The two variable defective keratin filaments 1PQ1 gene is located on chromosome 12q11.2-q13.3 and fields mostly congenital generalized type hyperkeratosis. The epidermis of matured keratinocytes consists of keratin filaments which are bound by a set of normal keratins associated proteins and are crosslinked by transglutaminases. They appear as cytoplasmic granules and have very efficient on cross linking keratin filaments within the cell. On genetic analysis, deletion of keratin 1 gene would lead to disruption of keratin filaments of granulocytes and basal layer which of course is further confirmed by biopsy. Knockout keratin mouse which lost K1 and K10 gene with severe EHK further confirms the function of keratin 1 and 10 on non-epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Genetic form of keratin 5 and 17 abnormality would also give rise to palmoplantar type of epidermal likely palmoplantar type EHK. In adolescence there is partial remission possibly due to cessation of keratin 10 mutation 1818 C > T. Multiple terms have been used to describe EHK: EHK of the vulva an abnormal pattern of keratinization which can occur in the context of biliary conduit failure, chronic topical irritations, a variety of infectious agents, and vitamin A deficiency. The fetal variant has been reported in congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma.

Rheumatologic Manifestations

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EH) is a genodermatosis condition of abnormal skin formation leading to blisters on the skin surface. Other names include ichthyosis bullosa of the newborn and bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, which is a keratinization defect in the epidermis. EH occurs due to mutations of keratins gene on chromosome 12 and 17, KRT1 and KRT10. The histories include scaling and plate-like plaques densely distributed over face, scalp, trunk, and extremities developed soon after birth. Erythroderma of scalp and ears, with erythema, crusts and scabs. On histopathological examination, the scales with keratin occlusion in the pores and erosions and crevices on the undersurface are classical histopathology findings of EH. Rheumatologic manifestations include palmar fasciitis with polyarthritis, eosinophilic fasciitis, systemic sclerosis, and dermatomyositis with underlying malignancy are rare paraneoplastic syndromes which mainly affect middle-aged women. Rheumatologic symptoms vary in manifestations and response to treatment, and paraneoplastic syndromes may be the initial presentation of a malignancy. This report includes 8 Han Chinese patients diagnosed with EH-associated rheumatologic and immunologic symptoms, and summarises the clinical features, treatments and outcomes. To date, there are no reports of rheumatologic manifestations associated with EH. Six patients, 5 women and 1 man, aged 46–79 years, were included in the study. Patients 1, 2, 5, and 6 had family histories of EH, while the other two were sporadic cases. Patients 1 and 5, aged 46 and 54 years with long-standing EH, suffered from pain and swelling in palmar areas for 2 years. Finger swelling with deformities, pain, swelling and swelling in wrist and shoulder joints developed subsequently. Patient 1 had normal laboratory examinations except for mild increase of markers of inflammation. A mechanical workshop was injected with corticosteroid. Grade 1 structural change of the 2nd metacarpophalangeal joint was noted. A large study cohort of biopsy specimens is necessary to obtain conclusive results.

Joint Pain and Inflammation

In the mounting body of literature on epidermolytic hyperkeratosis—whose manifestations primarily occur within the skin—a rising exploration of systemic manifestations is emerging. Inflammatory arthropathy has been reported in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis by three groups. The phenotypic presentation has not been previously described: a patient with mottling of the skin, serrated ridging of the nails, and a presentation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis unclear if new or concurrent. Literature specifically mentioning joint inflammation in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is scant, though much has been published regarding inflammatory arthropathy among other forms of ichthyosis [4]. However, whether this joint pain and inflammation were attributable to epidermolytic hyperkeratosis or a new diagnostic entity remains unknown. In either scenario, the uncertainty of this diagnosis led to far-reaching implications for management and treatment, ultimately necessitating the collaboration of various specialties. Therapy for epidermolytic hyperkeratosis primarily focuses on symptomatic management of epidermal cracking and fissuring [1]. The consideration of systemic medications, beyond topical and intralesional therapies, remains scant. As additional cases are described, better understanding of systemic involvement and management of joint and visceral symptoms is anticipated. There is far-reaching pharmacotherapeutic consideration given clinical severity, comorbidities, and suitability for systemic treatments on a case-by-case basis. There have been anecdotal usages of multiple systemic treatments; consideration of systemic medications or therapy should be in consultation with a specialist and be based on the medical history presented.

Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

Pachyonychia congenita, a rare keratin disorder due to mutations in the KRT6A and KRT16, has been recorded in one case of juvenile polyarthritis. This observation pointed toward a possible genetic association in these conditions. On the other hand, different types of acquired immune-mediated inflammatory diseases have been occasionally described over the years in EHK patients. In fact, some cases of bullous pemphigoid occurring in EHK have been reported, producing conflicting data on this possible association. In one case, both diseases manifested in the same body site, such as occlusive points. These conditions are clinically and pathogenic implications of local pH variations, inflammation, and altered proteolytic activity. Furthermore, local skin irritation and trauma were mentioned to trigger the development of BP lesions. A second publication added other EHK patients to the reports to support this possible association, but it admitted that the age at onset of BP and EHK were only indirectly suggestive of this clinic-pathologic association. In the last decades, autoimmunity has been reported in EHK, particularly anti-interfilament cytolysate antibodies. Other findings, among them IgM anti IgG antibodies, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, increased CD8 T-lymphocytes and CD4/CD8 ratio, and positive antinuclear antibodies, have been reported to possibly correlate with the severity of EHK. Although this information raises the question concerning pathophysiologic factors of autoimmunity in EHK, knowledge about this condition and the most classical autoimmune rheumatic diseases remains scant. A general systematic review of the literature of all the autoimmune rheumatic diseases with possible acquired or genetic associations with EHK is lacking. Thus, here, this associate is reviewed, choosing the most frequent, classical, and better characterized autoimmune diseases. The paper mentions only a few specific manifestations of less common immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, the following need to be mentioned regarding this type of immune-mediated inflammatory disease as compared with the specific ones described above. Both juvenile idiopathic and acquired inflammatory arthritis, such as RA, occur relatively frequently in EHK patients. The association is compatible with an underlying common pathophysiologic mechanism of altered innate immunity and chronic inflammation. The relative prevalence of these two types of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and related comorbidities is not evident in adult-onset, non-French EHK patients.

Muscle Involvement

Tubulointerstitial Inflammation Induced by Medullary Nephrocalcinosis Induced by Erythropoietin in SLE: A Case Report Tubulointerstitial Nephritis and Medullary Nephrocalcinosis Induced by Erythropoietin in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) [5]. The significance of muscle biopsy in the diagnosis and management of these sclerodermalike syndromes is yet to be resolved but may provide a clue to pathophysiology. To the best of our knowledge, the present case is a novel combination of stiff skin syndrome and an inflammatory myopathy. Herein, we report a woman who presented with slowly progressive skin thickening over the face, neck, and upper chest associated with new onset muscle swelling and weakness. Dermatomyositis is a chronic inflammatory myopathy characterized by symmetrical proximal muscle weakness and distinctive skin manifestations. It mostly occurs in children and adults [6]. The anaphylactic and cutaneous symptoms presented in these cases were identical to those described in previously published cases. On the contrary, the unique findings described herein have not previously been reported in dermatomyositis in children. The absorption of dermatomyositisrelated autoimmune diseases facilitates a differential diagnosis of this category of vasculitis, which is important for treatment strategies.

Immunologic Manifestations

The wheals and hives are the most commonly recognized surface manifestations of an allergic reaction and are generally a temporary thing that is easily treatable with anti-histamines or even ice. These hives occur because the body has become sensitive to an allergen or some chemical that has become intolerable to the system. The result is swelling and cruel itching that can be painful and sometimes proceeds to weeping surfaces. This is another of those immunologic responses that can be a pain in the soft tissue for the sufferer and annoying to be around for everyone else. It is commonly referred to as “hives” and can rear its ugly head for any number of substrates, including food, vapors, stress, pet dander, chemicals on the skin, etc. Most people suffer a hive outbreak episode once or twice in a lifetime, however for others, this is chronic and on-going. Hair loss is another subject of recognition faced by the majority but addressed with extreme care by many, because it is such a sensitive and personal issue. Young females are particularly sensitive to this even though loss is temporary and certainly not life-threatening. As in the case of allergies, some hair loss is just a natural shedding that goes on all the time; however, when this falls outside of the standard, it can provoke reactions that manifest in many ways including through immunologic response. Stress is a common trigger of hair loss with classic effects of causing hair to fall out in clumps or be pulled from the follicle with a shearing force. This triggers a “reactive” inflammatory response that heals and remediates the damage but in doing so may provoke a chronicity to the autoimmune response that propensively harms the hair follicle not permitting normal recovery and leading to permanent and total hair loss. Children and young adolescents are particularly vulnerable to a particular type of alopecia called Areata which can result in random patches of hair loss as a distinct form of a self-destructive flaring inflammatory cycle. Certain types of lupus can also experience large patches of hair loss brought on by chronic and damage-driven inflammation. In these lupus presentations the skin is simultaneously the surface and the internal body. The thick curled hair of the scalp is replaced by shorter and finer hair that has little pigmentation and this patch on the head can be extremely painful because of the passive perforation of the skin and all its delicate sensors.

Altered Immune Response

The investigations reported above raise the question of whether the altered immune response in EH is viewed simply as a posteriori phenomenon secondary to the conduit epithelial damage or it activates atopic mechanisms that themselves were responsible for the substrate’s predisposition to lesions [7]. The controversy on various aspects of the conceptualization of EH as an atopic disorder is still unresolved. Some inflammatory cells, including mast cells, dendritic cells and T lymphocytes are present in neopterin-producing skin at lesions’ onset, and at later stages or in more extensive lesions are observed vigorous exocytosis or cell death in keratinocytes and infiltrating leukocyte populations, with preferential involvement of macrophages, T lymphocytes, dendritic and natural killer (NK) cells and Ig-producing B cells [8]. Far less data though are available on the endogenous mediators (or their abnormalities) alongside which atopy, probably allergen-independent, and eczema prevail. The humoral response at this level, via the production of chemokines, prostanoids, lipid mediators, and cytokines, has been less formally investigated in EH. The other levels of clinical and experimental response aside from mast cell degranulation were not formally considered, but mast cell numbers in the upper dermis increase and more than 60% begin to degranulate throughout the epidermis of the lesions, reflecting the initiation of responses conditioned by both IgE-independent and IgE-mediated activation of tissue resident mast cells and the second recruitment of connective tissue mast cells at later states. The redistribution of vasogenic mediators alongside which these changes take place need to be identified. While adaptation to chronic inflammation, together with the development of eczema, were documented apparently on an unresolved substrate with prerash atopy, the absence of pre-existing atopy was evidenced at this level too, arguing for a primary localization-depending defect similar to that of keratinocytes, but this time much less studied.

Increased Susceptibility to Infections

The uncontrolled growth of epidermal cells can lead to many complications, particularly infections. -6 diseases lead to infections of viral, bacterial, or fungal origin due to a variety of disorders such as alteration in keratinisation, epidermal barrier dysfunction, loss of HHV-10 receptors and change in cutaneous microflora which immunologically and non-immunologically predispose a person to infection [9]. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is one such disorder where genes related to keratin are dysfunctional which leads to excessive epidermal thickening and keratinisation which causes crusting of the skin and predisposes to infections. The excessive keratinisation involves keratin 1 and keratin 10 especially in superficial epithelium which leads to blister formation and the epidermolytic hyperkeratosis involving keratin 9 and keratin 14 leads to palmoplantar keratoderma which is considered to be the latter form of hyperkeratosis [10]. The skin becomes more infected due to hyperkeratinisation as the patients may limit contact with the environment which may predispose to pneumococcal infection, or may come in contact with infected children which may predispose to viral infections such as herpes simplex (primary extraoral or genital infection) which is mediated by immune response and is often severe. The excessive crusting leads to superadded bacterial infections from staph or streptococcus which present with maintained fever, redness, and oozing cracks. Poor personal hygiene leads to fungal infections as well. The extensive crust on the skin limits airflow and leads to a hot and humid environment which leads to fungal infections, commonly candida and dermatophyte. The use of topical antifungals is effective for fungal infections.

Diagnosis of Epidermolytic Hyperkeratosis

Diagnosis of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is made by clinics and histology. The age of the patient, distribution of the lesions, and morphology help narrow down the differential diagnosis. The clinical findings are often sufficient to make the diagnosis of the common forms of ichthyosis, in particular, x-linked ichthyosis vulgaris, lamellar ichthyosis, and keratinopathic ichthyosis [2]. Ichthyotic skin shows increased thickness with variable help. The process involves thickened stratum corneum with parakeratosis, secondary keratinocyte degeneration in the granular layer, and sometimes microabscesses with neutrophils in the upper epidermis. Obtaining a tissue section with a first biopsy is often a problem. The first biopsy may provide little information or show anomalous findings outside the ichthyosis area. The second specimen is often much more diagnostic. A common type of ichthyosis associated with prenatal blistering may show ichthyotic changes in a biopsy taken soon after delivery or in some cases weeks after delivery.

Clinical Evaluation

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) has been classified as both a distinct entity and a histologic reaction pattern in the last decade. On one hand, it presents as a primary, profound alteration of the epidermis or an associated stromal factor, giving rise to epidermal hyperproliferations, which in turn lead to the clinically recognized conditions. In this case, it is classified as the EHK group of conditions. Alternatively, it arises secondary to conditions whose primary change occurs beyond the epidermis and which develop epidermal alterations secondarily, usually with a secondary feature of keratinocytic-layer disruption [1]. In this case, it is classified as a histologic reaction separate from the EHK group of conditions. In the past few years, the latter group has been considerably broadening, with a plethora of conditions newly described as showing EHK in their epidermal alterations. Of these conditions, some have been identified as being separate from the ones that fall under the EHK group of conditions. These include epidermolytic keratosis (EK) associated with vacuolar/degenerative spongiosis, benign seborrheic keratosis with EHK, or EHK forming within an epidermal nevus. Some cases of epidermal nevi showing EHK initially led to misleading diagnoses of EHK prior to their subsequent resection and definitive diagnosis as nevus. EHK was also seen in keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas after chemotherapy and in areas of co-existing solar keratosis. Mechanistically, teeming literature has emerged on the mutations in genes encoding for keratinocyte structural proteins, which end up leading to posterior alterations of the epidermis presenting as EHK.

Histopathological Examination

A critical feature in diagnosing EH is the histopathological examination of a punch or shave biopsy. The specimen is usually prepared as an unstained section coverslipped in Canada balsam. A reexamination of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain may result in EP enrichment and is sufficient in rare cases [2]. The features of topically treated versus untreated specimens are similar, with some additional changes. Thus, in biopsies from patients with a successful treatment, a more uniform cornified layer thickness can be recognized and a significant reduction in suprapapillary keratinocyte vacuolation may exist. The only feature of epidermolytic ichthyosis that persists with topical retinoid treatment is a basket-weave appearance of the cornified layer (stratum corneum). Young children also show a higher frequency of maturation errors in follicular duct and sebaceous gland keratinization than adults. In treated patients, better-formed duct structures can be seen. The findings of younger children resemble seborrheic keratosis and acanthoma. The precise temporal relationship of these events is unknown. However, observations suggest that the keratin enigma is influenced by the physician– patient relationship and that it reflects the effect of ultraviolet light upon IL interactions. A significant reduction in vacuolation quantity and severity of subepithelial blister formation and scab crusting was reported after treatment. New blisters continued to appear, but their paleness and the rate of blister resolution improved. In these patients, initially nonviscous and clear blisters evolved into milky ones and later, almost transparent small nodules. During up to 30 months of isotretinoin treatment, new lesion appearance, lesion turnover/persistence, and blister rupture persisted and increased in frequency but were not individually scabbing. The clinical response time was variable. A reduction in blister production usually occurred after a few days, with persistence of some blisters that later became crusted and resolved, and full remission often necessitated several weeks.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing for the molecular diagnosis of EH should be offered and is usually performed with next-generation sequencing. The most prevalent known mutations are missense mutations in KRT1 or KRT10, resulting in a glycine-to-cysteine substitution at either residue 145 (G145C) of KRT10 or residue 171 (G171C) of KRT1. These mutations cause increased rigidity and misfolding of keratin intermediate filaments at the suprabasal level and thus lead to abnormal filament aggregation, expansion of the cytoplasmic perinuclear keratin filament basket, and subsequent cytoskeletal collapse, which has been shown to elicit an inflammatory response (2). This previously unreported form of EH was diagnosed by skin biopsy, showing vacuolar degeneration of the upper epidermal layers and absence of internal keratin filament aggregates on immunohistochemistry, as well as whole exome sequencing of relatively common mutations in KRT1. More recently, a 13-yearold boy with EH sine EH was found to have a heterozygous de novo mutation in the splice acceptor site of intron 4 of KRT14 (c.673−2A>G), which is predicted to lead to inclusion of intron 4 in KRT14, resulting in a prematurely truncated protein. This mutation was previously found in another patient with KRT14-null PEH. Thus, the spectrum of genetically resolved EH cases appears to be incomplete, and mutations in other genes such as KRT2, KRT17, and KRT31 that may predispose to the development of EH are likely to remain undiscovered due to small mutation effect. Skin biopsy confirmation of EH is critical for determining the need for genetic testing. In families with a known history of EH, genetic testing can be offered before prenatal or preimplantation diagnosis. However, in sporadic cases, it is first mandatory to confirm EH by skin biopsy as there are no known early-onset diseases to be tested for which EH-associated genes are implicated.

Management Strategies

The mechanisms underlying the rheumatologic and immunologic manifestations of EHK are poorly understood, making it difficult to formulate targeted treatments. Hence the treatment is based on expert opinion and focused on symptomatic management. Rest, analgesics and anti-inflammatory treatment are all generally advised. For the musculoskeletal manifestations, topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with or without oral drugs of the same class can be attempted in the first instance. Other treatment options include disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Methotrexate is usually the drug of first choice in children. Abatacept, a costimulation inhibiting agent, has been used in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, which is the beststudied EHK-associated rheumatologic manifestation. For severe forms of the disease, biologics such as tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors can also be attempted. However, experience with these agents in resolving EHK-associated rheumatologic disorders is still anecdotal [11]. For the immunologic manifestations, topical steroids and/or calcineurin inhibitors are often employed for local lesions. For extensive mucosal disease, systemic corticosteroids are used, often with azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil for azathioprine- or steroid-resistant patients respectively. Other forms of managements may also be undertaken, such as phototherapy or botulinum toxin for EHK-associated hyperhidrosis or corrosive esophagitis, carbon dioxide laser therapy for perioral and vulvar lesions, trichloroacetic acid peels for palmoplantar keratoderma, and surgery for scarring and debilitating lesions. The basis for these treatments is largely anecdotal and much remains to be done to better understand the mechanisms underlying these manifestations and to translate that knowledge into better management strategies. EHK is primarily a keratinization disorder in which the genetic basis has only recently been understood, but only rare reports exist on the associated rheumatologic and immunologic manifestations [1]. Cases of EHK associated with or following the development of system or local autoimmune conditions are also rare in the literature. Following this report, a brief review focusing on the rheumatologic and immunologic manifestations of EHK is provided.

Topical Treatments

The treatment of localized EHK has focused primarily on topical modalities. Emollients provide the most symptomatic relief. Intensive use of thick ointments such as petrolatum or 50:50 mixtures of white petrolatum and lanolin or paraffin plus lanolin has provided variable benefit. With concurrent moderate use of emollients, low to mild strength topical steroids are sometimes effective in alleviating pruritus, but are ineffective in reducing the hyperkeratosis. Over-the-counter keratolytic creams containing 2-3% urea, ammonium lactate, lactic acid, or salicylic acid are helpful to some degree. Creams containing higher concentrations of urea (up to 40%) may be more irritating and exacerbate pruritus. These topical preparations are most effective on thin areas of the skin including the palms and soles. However, localized keratinization persists despite a long duration of treatment. Combination of emollients and milder keratolytic agents improved pruritus, but papules persisted. Occasionally locally destructive therapies such as cryotherapy, curettage, and electrodessication and cautery have been described, but these painful destructive treatments can lead to scarring and resultant unwanted complications. Moreover, the coarse dermatitis could intermittently become inflamed despite fruitless attempts to treat with super potent topical steroids and topical estrogens. So far, calcineurin inhibitors have not been mentioned in the literature as a treatment option for the cutaneous lesions of EHK. Topical calcineurin inhibitors were sometimes helpful in diminishing the inflammation of other inflammatory skin diseases that were added in brushed areas, but could not clear the thick keratotic plaques and were alternating with topical potent steroids. On resistant areas such as the scrotum, a 4-week course of 5% imiquimod ointment, a topical immunotherapy, reportedly led to complete resolution of the indicated lesions (with 16 recurrences). Although phosphorothioate oligonucleotides are known to safely ameliorate or prevent early-onset variants of EHK in transgenic mice, the potential painful inflammatory side effects of applying imiquimod on sensitive localized body sites and possible systemic side effects should be considered [1].

Systemic Therapies

Systemic treatments include etretinate, cyclosporine, retinoids, and methotrexate. Acitretin or its parent compound, etretinate, are both effective systemic treatments for EPS. Early studies on etretinate showed remarkable efficacy in EP patients, warranting further investigation of analogs with more favorable pharmacokinetic and metabolic behavior. Oral retinoids, particularly acitretin, have also been successfully used to treat adults with severe EP. Acitretin, at an initial dose of 25 mg/d, can be increased every 2–4 weeks until the maximally tolerated dose is reached. Laboratory monitoring of liver enzymes and triglycerides is recommended every 4–8 weeks. Erythrodermic flushing, systemic retinoid therapy initiation, and phototherapy can lead to significant side effects, but resolve once treatment is switched to topical or other agents. The most frequent adverse event associated with oral acitretin therapy is dryness of the skin and mucous membranes. Combination therapy with methotrexate or cyclosporine can ameliorate the side effects of acitretin. Additional systemic agents to treat EPS include cyclosporine, other retinoids, dapsone, methotrexate, adalimumab, infliximab, and mycophenolate mofetil. Recommended treatment for patients diagnosed with EPS involves phototherapy or acitretin. EPS may develop or worsen in patients who start therapy with methotrexate, biologics, or systemic agent treatments directing against the immune system. Patients who develop EPS after such therapies usually respond to acitretin or phototherapy. Methotrexate is the second-line agent, with adalimumab, infliximab, and mycophenolate being third-line agents. Low-dose methotrexate with folic acid supplementation is the most commonly used systemic therapy for chronic plaque psoriasis surfacing the joints. It may be helpful in managing psoriasis flares, despite a slower onset of action and lower efficacy than acitretin and the retinoid family. Methotrexate has been employed as a first-line agent to treat EPS after case reports of the use of high-dose apremilast. Methotrexate has not been effective in controlling EP, requiring switching to a different systemic agent with an immunosuppressive effect. Methotrexate can be used safely and effectively when treating cases of EP surfacing on unexposed skin areas, but could be considered the third or fourth-line agent for cases surfacing over larger body surface areas compared to at the same level as acitretin-sensitive EP patients.

Supportive Care

Supportive measures are essential both before and after aggressive therapies designed to replace the defective gene or protein, as well as for patients who require palliative care. Prior to performing procedural interventions, education is essential to prepare patients and parents for what to expect as they undergo therapies. When possible, a trial period should occur so that patients become accustomed to being cleansed with topical preparations, emollients, or adhesives. Early emphasis should be placed on preventing further complications such as contractures, skin infections, and erosion of the corneal epithelium [11]. Early use of splints or protective materials can prevent the accumulation of vesicles in affected joints and allow patients to use their hands for feeding themselves, as well as prevent disfigurement of hands and feet. Use of bandage-like materials that glide over intact skin with friction can make self-care efforts less frustrating for both patients and caregivers. Considerably less pain is associated with water-only baths, and it is recommended that patients be well hydrated prior to bathing and that a trained person be present during cleansing to calm or distract the child. Although it may be necessary to tape the dressing to prevent slipping, adhesive which sticks to the exudate only rather than to the skin is recommended as this causes less discomfort during removal [1]. Dramatic improvement in the irritation and pruritus associated with scab formation can be promoted by frequent cleansing with oil or ointments on the lesions accompanied by control of infections and retraining in hygienic habits. Even with robust immunosuppression, hygiene measures and frequent drainage of vesicles can reduce both the wheal size and the irritable sensations remarkably. Painful vesicles are a hallmark of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. The blisters often result from the trauma of daily living and the resulting pain can be debilitating, despite some patients becoming desensitized. The conventional treatment of daily hot baths and wrapping with a bandage of soft cotton fabric is still the basis of treatment. There are anecdotal reports of phonophoresis and the topical use of clobetasol propionate in refining thickened areas of skin. Intralesional injection of steroids and Kenalog ointment are useful adjuncts. Local anesthetics may help relieve pain. A prompt, effective, and complete re-treatment with the above measures may be able to prevent future problems. Topical antibiotics are helpful to control infection but the ultimate solution is control of the blister formation.

Long-term Prognosis

The long-term prognosis of EHK is largely unknown. Murine models of EHK have shown abnormal hemidesmosome morphology that may destabilize the dermal-epidermal junction and lead to systemic manifestations 2. There is currently no documentation regarding systemic involvement in adults. Although there is one case of a 57-year-old female reporting bilateral uveal tract/mucositis, renal cysts, gynecomastia, alopecia, and a family history of skin involvement [1], other systemic sequelae such as conjunctival, stomatal, and airway affliction remain undocumented. The lack of involvement of keratin 1/10 expressing tissues likely explains the relatively mild symptoms seen in the adults with EHK. Despite the initial spontaneous improvement, a significant number of patients retain hyperkeratotic areas into adulthood. The initial scarring may be irreversible, although in the best case, at least mild eruption can be expected, at least to some extent. There is only limited personal experience of adult with epidermolytic ichthyosis sine epidermolysis. The patient had initial widespread blistering and erosion, healed with typical ichthyotic plaques which you could fortunately pass. The skin proved to be resistant to trauma for long periods of lip-air-vaporing. Life occasions such as oversleeping late would yield an awful, painful feeling of fresh eruption. Durable tonic therapy can hardly be achieved, as retinoids are reported to cause intolerable dryness of the eye. It may still mislead and lead to ruinous side effects, especially on healthy skin.

Quality of Life Considerations

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis caused by heterozygous mutations in either the keratin 1 or keratin 10 genes (KRT1 and KRT10). The cardinal histological findings consist of acantholysis and hyperkeratosis, and the classic clinical presentation includes blistering, warty, and/or velvety lesions in the flexural areas in young adulthood. Rarely, with chronic stimulation, a lichen simplex chronicus-like presentation is seen. If suspected clinically, biopsy/dermoscopy will often demonstrate the characteristic findings [1]. The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin. It is narrow, only 0.06–0.1 mm thick, but its overall length is considerable given the enormous area involved in body covering. The adult epidermis comprises 1500–1750 pairs of basal and keratinized layers. The entire epidermis is constantly regenerating and renewing, with a lifespan of 1–2 months. Keratinocytes continuously develop from the basal layer to the corneal layer and eventually shed off from the surface of the stratum corneum [12]. In terms of quality of life, EHK lesions are usually localized and well-defined. Admittedly, they differ considerably in size between each patient and may be even larger on occasion. EHK lesions may remain dry or cracked, and epidermal keratin scales evolve on chronic lesions. Due to its local nature, the impact of EHK on the quality of life might not be affected significantly for some patients. However, it should be mentioned that the concern of pre-cancerous changes may be raised by some patients on chronic EHK lesions with no consensus on when to biopsy. In addition, unforeseen adverse effects of aggressive treatments may result in far greater distress or loss of quality of life than preserving the pre-treatment condition. As a result, simple treatments to smoothen out and soften the hyperkeratotic lesions may be preferred by a number of patients.

Psychosocial Impact

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EH) is a rare form of inherited ichthyosis, with an autosomal-dominant and sporadic inheritance pattern, characterized by epidermal thickening with broad, strikingly undulating scales. They are distinct pathologically from the ichthyosis vulgaris caused by the filaggrin mutation. Although patients often present with atypical, horizontal linear markings at birth, the keratin and clinical findings of EH are traditionally interpreted as signs of harlequin ichthyosis, which is a severe autosomal recessive condition associated with a high mortality rate. There have been a few cases in older patients. These cases are instead recognized to represent late-onset cases of EH. According to the previously proposed classification, the childhood-to-adult type or late-onset type is characterized by a clinical history of mild term, limited extent, and progression to the apparent disease state in adolescence, pubescence, or later. The skin manifestations of late-onset cases of EH can resemble other forms. There was a 68-year-old woman with localized EH who developed lesions in her left palm and foot at the age of 61. A skin biopsy taken from the affected area at the age of 66 years was performed. Histopathologically, the stratum corneum was markedly keratinized, lamellated, and showed extreme elevation. There was a single, clear, internal cystic cavity in the epidermis. Specific keratins were only distributed in the part of the epidermis over the hyperkeratosis in the lesion but not in the unaffected skin. If an epidermal abnormality is severe, lesions may occur in early infancy in EH patients. However, such lesions may also develop in older age, as in the case presented herein. Cells producing specific keratins are likely involved in the pathogenesis in patients with this late-onset form of EH, besides expected mechanisms including microbial or mechanical irritation.

Research Advances

Structure and funding independent of the authors or sponsors. The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the article, or the decision to submit this article for publication. A. A. S. authored the article and is the guarantee for its content, including the data and analysis. People with eczema may have an increased risk for other immunologic or rheumatologic conditions relative to the general population. For example, atopic dermatitis has been associated with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis. Other allergic conditions, like urticaria and angioedema, are sometimes reported. The eczema-herpes connection has been long recognized, and seems to happen more frequently in those with atopic conditions. Eczema and itchy skin are also associated with non-allergic but immune-mediated cutaneous conditions, such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. Since these conditions can appear similar to eczema, inflammation of the skin goes unmanaged, and subsequent suffering can result. Reversal of therapy may be needed, should these conditions occur. Conditions outside of the skin include inflammatory conditions like asthma, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, conjunctivitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis. Additionally, there is a slightly higher risk of development of autoimmune diseases, including vitiligo, thyroiditis, and alopecia [11]. Lamentably, knowledge of such associations amongst both patients and providers is sometimes lacking. An awareness of these and potential means of management may be useful for the prevention and earlier diagnosis of these additional afflictions. Eczematous appears to be one of the most common dermatological problems presenting to the primary care physician (PCP). The prevalence of atopic dermatitis rises above 10% in some populations, with even higher figures worldwide [1]. Puberty commonly provokes an increase in activity, but is not invariably the only clear cut-off for management. Nonetheless, most children (70%) have remission by adulthood, although mild to moderate manifestations and itch may persist.

Current Clinical Trials

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is one of the congenital ectodermal dysplasias, group of disorders affecting the embryological ectoderm. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis are the one of the epidermal nevus syndromes due to genetic mutations in keratin genes leading to the defective keratin hyperkeratinization and aberrant keratinocytes differentiation. EHK is considered a rare genodermatosis and is one of the most important keratin disorders. EHK has two modes of inheritance sporadic mutations giving rise to the classical disease or mutations in the keratin 9 resulting in mild palmoplantar EHK. A mutation in the keratin 1, 10, 14, 16 or 17 gene causing the classical EHK phenotype. The earliest presentation is usually at or shortly after birth, but it may occur later in life. The diagnosis is clinical, both from the appearance and the morphological features on histology. The increased benzoyl peroxide investments in treating acne vulgaris and previous reports of epidermal inclusion cysts and a pre-existing diagnosis of severe cystic acne, there was a high index of suspicion for an adverse effect of benzoyl peroxide treatment inducing an acantholitic disorder. No other medications other than topical benzoyl peroxide were administered. The topical medication was changed to a clindamycin lotion during which, a marked improvement in the condition was seen. Keratin mutations lead to basal cell blistering and in the absence of trauma, efforts should be directed towards identifying medication or environmental triggers to ascertain common pathogenic pathways [13]. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is a unique type of EHK which is caused by keratin gene mutation and is transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner. It typically manifests as erythematous plaques since infancy progressing into thickening and the skin has a wavy and trunk like appearance. The palms and soles are commonly spared. In adults, it may predispose to the development of squamous cell carcinoma [1]. Scalded skin syndrome or generalied blistering dermatosis is hardly reported due to the variety of clinical presentation of EHK.

Future Directions in Treatment

Comprehensive research is demanded in order to develop effective immunomodulating therapies that could alter the disease processes in EHK. Although research on systemic immunosuppressive therapies for similar keratinization disorders has gained traction, most of these treatments remain in the preclinical phase. Histopathological studies utilizing comparable immunosuppressants are needed in EHK ferritin aggregation models. Currently, pharmacological agents such as Apremilast, Dupilumab, and Capicoltriol rapidly underwent translational application to EHK patients as well [1]. It would be beneficial to explore other drugs from the immunomodulatory spectrum to redesign therapeutics for this unmet need. Tolerance-mediating treatments that involve the importance of lipophilicity and pH in drug formulation pliability may be of particular interest. The enhancement of conjugated linoleic acids with clinical evidence of safety may hold promise for EHK prevention. In addition to chemical modulation of immunogenicity, whole-cell virotherapy utilizing the oncolytic Vesicular Stomatitis Virus is presently being studied in the treatment of other inflammatory diseases, and modeling its efficacy for EHK treatments may be fruitful. In addition, a longitudinal study including a cohort of EHK patients with standardized scoring systems is needed to provide real-world evidence and a clinical platform for piloting novel therapies thereafter [11].

Discussion

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is a rare genetic disorder that has widespread organ system effects yet is most commonly presented with skin findings. A six-month-old boy was referred for management of widespread erythematous scaly plaques and blisters that had developed shortly after birth. The family history was notable for a sister with similar findings. At presentation, the patient was globally ill-appearing with extensive plaques of erythema and scaling, and areas of crusted blistering with erosion. Broad disorganized layers of keratin were present in the epidermis, diagnostic of EHK. Next-generation sequencing of the KRT1 and KRT10 genes was notable for an inherited heterozygous missense mutation in KRT10, consistent with the diagnosis of EHK. The condition was managed supportively with emollients and keratolytics. The severity of the disease could go from mild to very debilitating. Complications include infections, keratitis and conjunctival keratinization, deafness, skin cancer, and squamous cell carcinoma. EHK may occur not only as an autosomal dominant skin disorder but the most severe phenotype also with constitutively inactive p53. EHK is now known to be caused by inherited or de novo KRT1 and KRT10 mutations, as well as a rare missense mutation in KRT2A. This 57 year old woman presented with a remarkable personal and family history of severe skin fragility, acral blistering, and whitish plaques of entire body and orifices since birth. Other findings included onychodystrophy, thickening and hoarseness of voice, corneal keratopathy, and tardive oculogyric crisis over years due to repetitive telotristat use. These keratin disorders have been shown to cause a concatenation of degenerative patterns that precede premature cell death in an aggregate of differentiated basal keratinocytes. Dysfunction of keratin and its assembly is implicated in autosomal dominant non-epidermolytic ichthyosis. This is a childhood disease that is distinguished by generalized fine scaling, prognathism, keratosis pilaris, and follicular spiny outgrowths, which may result in secondary deformities. KRT1 mutations have been shown by next-generation sequencing and truncating allele misses in this family. The abrogative p.1679C7 frameshifting mutation is not present in blood, indicating somatic mosaicism and proving a pathomechanistic role in EHK. Individuals with EHK generally develop a mild to moderate skin phenotype in the first year, which later coarsens and exacerbates in adulthood, often with palmoplantar keratoderma [1].

Recommendations for Clinicians

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is a genodermatosis that, like ichthyosis, has a heterogeneous etiology although most commonly it is due to mutations in either KRT1 or KRT10. The classic dermatologic manifestation of EHK is barrier skin over-hyperkeratosis from birth. However, in addition to severe hyperkeratosis, EHK has been associated with a variety of other conditions. The recurrent palmoplantar pustular psoriasis list of associated conditions is extensive and includes important systemic involvement such as cardiomyopathy and various forms of craniosynostosis. Recent reports of cases illustrating what is session two manifestations of EHK focus on the rheumatologic and immunologic presentations of EHK primarily affecting the joints, skin and occasional systemic involvement [1]. Keratin mutations producing an EHK phenotype have been associated with a variety of skin, rheumatologic and neurologic manifestations. Codenominal keratin mutations associated with EHK most commonly in KRT1 and KRT10 affect the coiled rod domains of these keratins forming dysplastic keratinocytes. The integrity of epidermis is impaired preventing adequate water retention and producing an inflammatory cascade resulting in ichthyosis and pustular skin lesions. This dysregulated epidermal barrier has been postulated to cause landscape changes in immune cell subpopulations as well. Shed keratinocyte products, including cytokines like IL33 or alarmins like IL1a and IL18, can activate these cells through pathways such as Caspase1/11, inducing secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines into the environment. Additionally, engagement of the IL1 pathways has been shown to facilitate the presentation of protein antigens by dendritic cells to naive T cells, allowing for memory T cell formation and production of pathogenic effector T cells. EHK state persistence may create chronic inflammation or even autoimmunity in affected individuals.

Future Research Directions

In addition to solidifying the evidence base regarding EHK skin manifestations through quality research, important basic science investigations need to be conducted. Given the aging of the EHK population and the impact of skin disease on quality of life, it is essential to determine vulnerable skin areas and identify evidencebased skin-care regimens for these areas. Scoring tools are needed to objectively assess skin disease burden or global skin improvement following an intervention. Also, it will be critically important to determine whether skin disease-associated changes in endogenous inflammatory mediators contribute to systemic symptoms or a pro-inflammatory state. Finally, it needs to be determined whether there is an association between SM and EHK severity and genetic mutation status [14]. In summary, important research is needed regarding the clinical spectrum of EHK skin disease and optimal palliation and disease modification. Recognizing and understanding disease manifestations will lead to more precise clinical diagnosis and treatment planning. More precise treatment exists to enhance the quality of life in affected patients and caregivers. It is essential that the medical and scientific communities work together to encourage research into these important aspects of EHK. The EHK community can help generate hypotheses for future research. In addition, the dermatologic community will then need to design and conduct research on this topic.

Conclusion

Since the initial description of EHK as a hereditary bullous ichthyosis [1], an increased appreciation of its clinicopathologic spectrum, which encompasses the hereditary ichthyoses, as well as their sporadic counterparts occurring in non-ectodermal neoplasms, has been noted. Study of these conditions in the genetic era is creating a greater understanding of the pathogenesis of the human skin from normal keratinization to disease. These proteomic studies have shed light on the ubiquitous nature of keratin abnormalities observed in EHK, and highlight the ubiquitous nature of epidermolysis. EHK has been recognized as one of the most common types of non-syndromic ichthyosis associated with keratin gene mutations. Due to the ubiquity of keratin in the epithelium, EHK can have systemic involvement, including extra-cutaneous manifestations. Dermatologic changes may aid in diagnosing systemic disease. Nevertheless, extracutaneous pathology may raise suspicion for EHK. Other organs, such as eyes, have also been rarely described. Dual diagnoses of EHK and other syndromic conditions or malignancies have also been relatively unreported. Only one prior case of dual diagnosis of a lymphoproliferative disorder and epidermolytic acanthoma/ EHK has been described. No simultaneous diagnoses of (true) malignancies and EHK have been published. Geographic tongue was previously reported in association with EHK. Systemic manifestations of EHK have been so seldom reported, that one of the few recent reviews of EHK did not note extra-cutaneous involvement at all. Increased awareness of these manifestations will allow for improved understanding of EHK as a manifestation of keratin pathway abnormalities, and the resultant increase in efficacy for management of the associated lesions as well as downstream systemic sequelae.

References

- Sachedina D, Villa-Ruiz C, Brem C, Sahni D. (2023) Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis of the vulva: Case report and review of the literature. NCBI. e325

- Eskin-Schwartz M, Drozhdina M, Sarig O, Gat A, et al. (2017) Epidermolytic Ichthyosis Sine Epidermolysis. 39: 1

- Uitto J, Youssefian L, Saeidian AH, Vahidnezhad H. (2020) Molecular Genetics of Keratinization Disorders – What’s New About Ichthyosis. 100: 5691

- Baldo F, Brena M, Carbogno S, Minoia F, Lanni S, et al. (2021) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Harlequin ichthyosis, a rare combination or the clinical spectrum of the disease? Report of a child treated with etanercept and review of the literature. 9: 80

- Vysakha Kavadisseril V, Rajalakshmi P, Sruthi SN, Muralidharan N. (2019) An unusual presentation of scleromyxedema as inflammatory myopathy. NCBI. 38: 13-16.

- Wang S, Keaton R, Kendrick Z. (2019) Severe Cutaneous Findings in a Woman with Dermatomyositis. 3: 222-225.

- Abreu-Velez MA, Klein AD, Howard MS. (2011) Overexpression of linker for activated T cells, cyclooxygenase-2, CD1a, CD68 and myeloid/histiocyte antigen in an inflamed seborrheic keratosis. 3: 1613.

- Esposito S, Guez S, Orenti A, Tadini G, Berti E, et al. (2016) Autoimmunity and cytokine imbalance in inherited epidermolysis bullosa. 17: 1625

- Brewer MG, Monticelli SR, Moran MC, Miller BL Lisa AB, et al. (2022) Conditions That Simulate the Environment of Atopic Dermatitis Enhance Susceptibility of Human Keratinocytes to Vaccinia Virus. 11: 1337.

- Khanmohammadi S, Yousefzadeh R, Rashidan M, Hajibeglo A, Bekmaz K et al. (2021) Epidermolysis bullosa with clinical manifestations of sepsis and pneumonia: A case report. NCBI. 86: 106258.

- Prodinger C, Bauer J W, Laimer M. (2020) Translational perspectives to treat Epidermolysis bullos-Where do we stand? NCBI. 29: 11121122.

- Jeon IK, On HR, Kim SC. (2016) Quality of Life and Economic Burden in Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. NCBI. 28: 6-14.

- Ablinger M, Felder TK, Wimmer M, Zauner R, Lettener T, et al. (2018) Basal pharmacokinetic parameters of topically applied diacerein in pediatric patients with generalized severe epidermolysis bullosa simplex. 13: 193.

- Verma R, Vasudevan B, Pragasam V, Deb P, Mitra D, et al. (2013) A Rare Case of Familial Reactive Perforating Collagenosis. NCBI. 58: 408.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.