Revision Surgery After Andrology Implantation in Australia Thirty-Year National Trends from Medicare Data (1994-2024)

by Nicholas Gillman*, Christopher Fraser, Jason Kim, Neil Smith

Department of Urology, Gold Coast University Hospital, 1 Hospital Boulevard, Southport, Queensland, 4215, Australia

*Corresponding Author: Nicholas Gillman, Department of Urology, Gold Coast University Hospital, 1 Hospital Boulevard, Southport, Queensland, 4215, Australia

Received Date: 04 February 2026

Accepted Date: 09 February 2026

Published Date: 11 February 2026

Citation: Gillman N, Fraser C, Kim J, Smith N, (2026) Revision Surgery After Andrology Implantation in Australia Thirty-Year National Trends from Medicare Data (1994-2024). J Surg 11: 11563 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011563

Abstract

Background: Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS) and Penile Prosthesis (PP) implantation are definitive surgical treatments for Severe Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) and Erectile Dysfunction (ED) respectively. Revision surgery is frequently required over time and represents an important marker of device durability and healthcare system burden. This study aims to characterise 30-year national trends in revision surgery following andrological implantation in Australia.

Methods: A retrospective, population-based observational study was conducted using Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) claims data from 1994-2024. Annual procedure counts for AUS and PP implantation, and revision/removal were extracted. Primary outcomes included annual revision volume and revision-to-total procedure ratios. Secondary outcomes included device-specific trends, age-stratified revision burden, and Medicare benefits paid for revision surgery as a surrogate of economic impact.

Results: Between 1994 and 2024, 20,355 implant-related procedures were recorded, including 5,936 revision surgeries (29.2%). AUS accounted for 7,474 procedures, with 2,418 revisions (32.4%), while PP accounted for 12,881 procedures with 3,518 revisions (27.3%). Annual AUS revision volume increased ~14-fold (CAGR 9.3%), outpacing growth in total AUS procedures (CAGR 8.7%). PP revision volume increased modestly (CAGR 3.5%). Revision burden was consistently higher for AUS than PP and increased with advancing age, exceeding 40% in men aged over 75. Medicare benefits pain for revision surgery increased ~ 6.7 fold over the study. Period, with AUS revision expenditure rising disproportionately and achieving cost parity with PP by the mid-2010s.

Conclusions: Revision surgery constitutes a substantial component of andrology implant practice in Australia. Higher revision burden in AUS and older patient populations highlights important implications for patient counselling and long-term health system planning.

Introductions

Severe Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) and Erectile Dysfunction (ED) contribute a significant burden in Australian men, particularly in older populations, and following radical prostate cancer treatment including radical prostatectomy and pelvic radiotherapy. In Australia, the age-standardised prevalence of ED is estimated at 21% and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), which may include SUI is 16% in men aged 40 and over [1]. This proportion is substantially higher post prostatectomy, with a reported 20% of men experiencing incontinence, and only 12% maintaining erectile potency [2]. In cases of severe SUI and ED, definitive surgical management may be necessary. Artificial Urinary Sphincter (AUS) and Penile Prosthesis (PP) represent definitive surgical management for SUI and ED respectively. Studies have demonstrated high rates of social continence and patient satisfaction following AUS implantation [3,4], and similarly high rates of patient and partner satisfaction following PP [5]. Revision surgery following andrology implantation may be required for a rage of device and patient related factors including mechanical failure, infection, erosion, mispositioning and progressive tissue-related complications [6-9]. As implant volume increase, and patients live longer with implanted devises, the cumulative risk of revision inevitably rises. As a result, revision surgery constitutes an important marker of device durability, patient selection and healthcare system burden. Existing evidence describing revision rates after AUS and PP implantation is largely derived from single centre series and device-specific registries, which are limited by small sample sizes, referral bias, short observation periods, and heterogenous follow up. While these studies provide valuable insights into mechanisms of failure, time to explant, device longevity, and allow analysis of individual patient data, they offer limited ability to characterise long-term, population level trends in revision surgery to evaluate howe revision burden varies over time across patient age groups. Moreover, data examining the economic implications of revision surgery at a national level remains sparse. In Australia, the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) provides a unique insight into longitudinal trends in implant and revision surgery at a population level. Analysis of MBS claims facilitates assessment of real-world practice and evaluation of system-level procedural and cost burden that goes beyond institutional series alone. It is therefore the aim of this study to characterise 30-year national trends in andrology implant revision surgery in Australia using MBS data. Specifically, the aim was to quantify revision burden over time, compare revision trajectories between devices, examine age-stratified patterns of revision surgery and assess Medicare benefits paid for revision procedures as a surrogate to examine the health economic burden of andrology revision procedures.

Methods

This study utilised publicly available, de-identified aggregate data from the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). The MBS captures procedures subsidised by the Australian Government. Annual procedure counts were extracted from 1994 to 2024 inclusive. Aggregated counts for each year were stratified by state of provision and age group. Individual data, such as indication, medical comorbidities and life of device is not available through MBS data. As data is publicly available, aggregate, and non-identifiable, formal ethics approval was not required.

Andrological implant procedures of interest were identified using relevant MBS item numbers

- Item 37432: Artificial erection device, complete or partial revision or removal of components, with or without replacement

- Item 37390: Artificial urinary sphincter, revision or removal of, with or without replacement

- Item 37429: Artificial erection device, insertion of pump and pressure-regulating reservoir

- Item 37426: Artificial erection device, insertion of, into one or both corpora

- Item 37381: Artificial urinary sphincter, insertion of cuff, perineal approach

- Item 37384: Artificial urinary sphincter, insertion of cuff, abdominal approach

The primary outcomes of this study were annual number of PP and AUS revision/removal procedures referred to collectively as revision surgery, and total annual PP and AUS counts. Secondary outcomes included revision to total ratio per year for both implant procedures and device specific trends. Descriptive statistic were used to summarise annual procedural volumes over time Revision to primary ratios were calculated annually to assess changes in relative burden over time. Items 37429 and 37426 can be billed together for patients undergoing inflatable prosthesis insertion, and as such to avoid double counting, these item numbers were combined and halved, with results rounded to the nearest whole number.

Results

Overall Implant Procedural Volume

Over the study period, 20,355 implant related procedures were claimed under the MBS. Of this, 7,474 (36.72%) were AUS related procedures and 12,881 (63.28%) were PP related procedures. Total annual implant volume increased progressively over the study period, reflecting a broader uptake of implantable urologic devices in Australian practice.

Artificial Urinary Sphincter: Total and Revision Trends

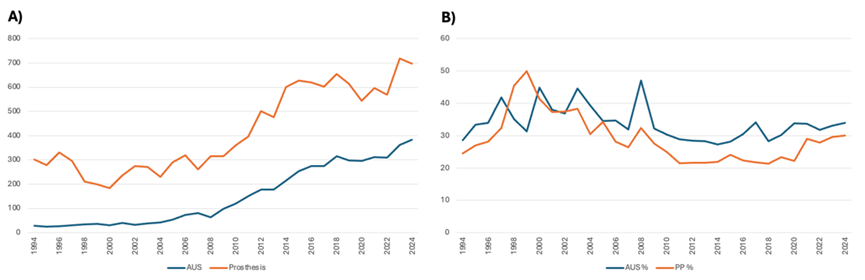

A total of 7, 474 AUS related procedures were claimed between 1994 and 2024 in Australia, of which 2,418 were revision or removal surgeries. This represents 32.35% of all AUS related procedures. Annual AUS revision counts increased from 14 in 1994 to 201 in 2024, corresponding to a 14-fold increase over the study period. This represents a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 9.3% for AUS revision surgery. Total annual AUS procedures similarly increased significantly over the study period, from 49 to 593 over the same study period, corresponding to a CAGR of 8.7%. Revision rates fluctuated throughout the study period, ranging from 27.3% to 47.1% annually. There was no clear reduction in revision rate over time. In most years, the revision to total AUS procedure proportion exceeded 30% with notable peaks in 2000 and 2008, where revision surgery accounted for 44.9% and 47.1% of AUS procedures respectively.

Penile Prosthesis: Total and Revision Trends

Between 1994 and 2024, 12,881 PP procedures were claimed nationally, including 3,518 revision surgeries, corresponding to an overall revision proportion of 27.31%. Annual PP revision counts increased from 74 in 1994 to 209 in 2024 (CAGR 3.5%), while total PP related procedures rose from 301 to 697 (CAGR 2.8%) over the same period. The proportion of PP revision surgery demonstrated a clear decline during the mid 2000s to early 2010s, followed by an increase in more recent years. In the mid to late 90s, revision surgery accounted for over 40% of total PP related procedures, peaking in 1999 at 50.0%. This proportion declined during the 2000s, reaching a nadir of 21-22% between 2011 and 2014. Over the last five years of the study period, this number rose and by 2024, revision surgery accounted for 30.0% of all PPI procedures (Table 1, Figure 1).

|

Device |

Total |

Revision |

Revision Proportion |

Revision CAGR (%) |

Total Procedure CAGR (%) |

|

AUS |

7,474 |

2,418 |

32.35 |

9.29 |

8.7 |

|

PP |

12,881 |

3,518 |

27.31 |

3.52 |

2.8 |

|

Overall |

20,355 |

5,936 |

29.16 |

- |

- |

Table 1: National volumes and revision burden for penile prosthesis and artificial urinary sphincter surgery in Australia, 1994-2024.

Figure 1: A) Total revision proedural counts for AUS and PP Claimed under the MBS in Australia 1994-2024.

B) Proportion of Revision Surgery for AUS and PP 1994-2024.

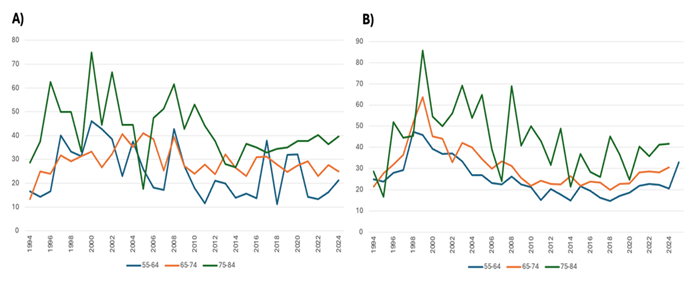

Age Stratified Revision Burden by Implant

Age stratified analysis demonstrates an increased revision burden with advancing age for both AUS and PP procedures. For AUS, the overall revision burden increased progressively across age groups, with a mean revision of 29.0% in men aged 65-74 and 42.36% in men aged 75-84. In the 55-64 year group, revision proportions were consistently lower across the study period (mean = 24.66%). Small numbers in the >85, and <55 age groups precluded meaningful analysis. Similarly, age-stratified analysis demonstrated a gradient in revision burden with advancing age for PPI. Mean revision proportion were 25.10% for the 55-64, 30.96% for the 65-74 and 43.41% for the 75-84 age group. In older men, revision proportions were consistently high through the study period, exceeding 40% in multiple years. Collectively, these findings demonstrate a substantial revision burden in older age groups for both AUS and PPI (Table 2, Figure 2).

|

Year |

AUS Total |

AUS Revision |

% Revision Burden |

PP Total |

PP Revision |

% Revision Burden |

|

1994-1999 |

323 |

110 |

34.0557276 |

1616 |

534 |

33.0445545 |

|

2000-2004 |

363 |

148 |

40.7713499 |

1196 |

441 |

36.8729097 |

|

2005-2009 |

698 |

251 |

35.9598854 |

1501 |

447 |

29.7801466 |

|

2010-2014 |

1334 |

380 |

28.4857571 |

2334 |

518 |

22.193659 |

|

2015-2019 |

2210 |

669 |

30.2714932 |

3118 |

704 |

22.578576 |

|

2020-2024 |

2582 |

860 |

33.3075136 |

3125 |

874 |

27.968 |

Table 2: Five Year Aggregated Revision Burden for Artificial Urethral Sphincter and Penile Prosthesis.

Figure 2: A) Age Stratified Trends in AUS Revision 1994-2024 in Australia Claimed Under MBS. B) Age Stratified Trends in PP Revision 1994-2024 in Australia Claimed Under MBS.

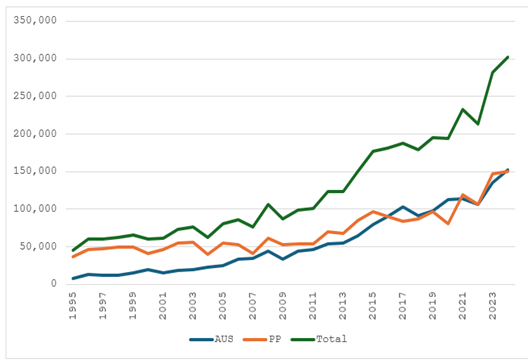

Medicare Benefits Paid for Revision Surgery

Medicare benefits for revision surgery following AUS and PP are available from 1995. From 1995 to 2024, total benefits paid increased from $44,894 to $302,462 per year, representing a ~6.7-fold increase. Medicare benefits for AUS rose from $8,111 to $152,398 (18.8-fold), while benefits for PP increased from $36,782 to $150,063 (4.1-fold). PP revision accounted for the majority of Medicare expenditure in early years, although the relative contribution of AUS revision increased progressively, with parity in annual Medicare benefits observed from 2016 onwards (AUS 50.4%m PP 49.6% of total benefits 2024) Figure 3.

Figure 3: Total Medicare Benefit Paid for AUS Revision, PP Revision, and Total Revision Surgery per Year 1995-2024 in AUD.

Discussion

In this national analysis of MBS data spanning three decades, we demonstrate that revision surgery contributes a substantial, and growing component of andrology implant surgery in Australia. Nearly one third of all implant-related procedures over the study period were revision or removal procedures, with revision growth outpacing procedural growth for both AUS and PP. AUS carries a higher, and more stable revision burden than PP, with revision burden increasing markedly with age. Over the past thirty years, Medicare expenditure for revision surgery has increased substantially, with AUS now matching PP in cost burden. Although artificial urinary sphincters and penile prostheses are considered definitive surgical management for severe SUI and ED respectively, revision or removal surgery is frequently required over time. Revisions may be necessitated by device-related factors such as mechanical failure may occur in the tubing, cylinders or valve pump in PP, and component malfunction or fluid loss may occur in AUS [6,10]. Other device factors include device mispositioning, herniation, infection, erosion and urethral atrophy [6,7,10]. Patient related factors including previous pelvic radiotherapy, obesity and cardiac comorbidities have also been associated with increased risk of infection, erosion, and mechanical failure, which may necessitate revision or explant surgery [9]. Longitudinal studies report cumulative reoperation rates for penile prostheses of approximately 11.2% at 5 years and 15.7% at 10 years with mechanical failure being the most common indication for revision [11]. Beyond 15 years, reported re-operation rates vary widely, ranging from 11 and 40% [10], with median device longevity estimated at approximately 20 years [12,13]. For AUS device longevity is generally shorter, with a median revision-free implant survival rate of 10.8 years with a 75% explant-free survival rate at 5 years [14]. The estimated 5-year and 10-year overall revision-free survival rates for AUS are 60% and 40% respectively, with nonmechanical failures such as urethral atrophy being the primary cause for re-operation [6,15]. Experience from orthopaedic implant surgery demonstrates that younger patients with longer life expectancy are at increased risk of revision surgery, largely because they are more likely to outlive the functional lifespan of their initial implants [16].

A similar principle seems applicable to andrology implants. A large burden of urology implant surgery is following radical treatments for prostate cancer [3], which has demonstrated improved survivorship over time [17]. As patents live longer following AUS or PP implantation, the cumulative risk of mechanical failure, erosion, infection and other device-related complications increase, necessitating revision or replacement over time. In parallel, advancing age increases comorbidity burden which may elevate the risk of device-related complications, such as metabolic and cardiovascular disease.The consistently higher, and less variable, revision burden observed for AUS compared to PP likely reflects fundamental differences in device complexity, anatomical environment and failure mechanisms. Mechanical failure represents a common indication for both devices, however non-mechanical complications such as urethral atrophy are more specific to AUS and contribute significantly to its revision burden [6]. Additionally, prior pelvic radiotherapy, which is increasingly prevalent among prostate cancer survivors, has been associated with a markedly increased risk of AUS erosion and infection, with reported risk of explant or revision as high as 7-fold greater than non-irradiated patients [18]. Comorbidities further exacerbate these risks by impairing tissue integrity and wound healing. Collectively, these factors likely underpin the persistently higher and more stable revision burden observed for AUS relative to PP in national practice. Age emerged and a key determinant of revision burden in this national analysis, with a clear and consistent gradient observed across advancing age groups. For both devices, revision proportions exceeded 40% of national activity in men aged 75 and older; substantially higher than those observed in younger cohorts.

This finding aligns with prior literature demonstrating that age influences the likelihood and mechanism of revision surgery. While younger patients are likely to require revision over their lifetime due to longer survival and device wear, older patients appear to face a higher short to medium term risk of device-related complication, likely reflecting reduced tissue resilience and greater comorbidity burden. Notably, despite higher complication and revision rates reported in older men, several studies have demonstrated comparable device survival and patient satisfaction in appropriately selected men aged 75 years and older undergoing AUS and inflatable PP implantation [19-21]. These findings underscore the importance of nuanced, individualised counselling and shared decision making, in which age along should not preclude implantation, but the elevated risk of revision in older patients should be explicitly discussed as part of a longitudinal treatment strategy.Revision surgery for andrology implants represented a growing and predictable healthcare cost. Medicare benefits paid for revision surgery increased ~6.7 fold over the study period, with revision AUS related expenditure rising disproportionately and achieving cost parity with PP revision by the mid 2010s. These figures underestimate the true economic burden, only capturing procedural reimbursement, and fail to capture device cost, hospitalisation fees, hospital readmission, or management of device-related complications. This study’s strengths include its national scope and longitudinal analysis over three decades of implant surgery in Australia. However, MBS data is aggregated and lack patient level detail, precluding adjustment for comorbidity or radiotherapy exposure, assessment of time -to -revision and indication for primary implant or revision/explant. Coding accuracy is assumed, and underestimates total national activity, failing to capture procedures completed in the public sector. Medicare benefits reflect procedural reimbursement only and do not account for total expenditure. Despite these limitations, the data provides robust insight into system-level revision burden.

Conclusion

Revision surgery following AUS and PP is common, increasing, and predictable at a national level. Approximately one-third of all implant-related procedures are revisions, with higher and more stable revision burden observed for AUS, and in older patient populations, alongside a substantial rise in associated Medicare expenditure. These findings have important implications for patient counselling, and health-system planning for andrology implant surgery.

References

- Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, Cumming R, Wittert G, et al. (2005) Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet 366: 218-224.

- Heathcote PS, Mactaggart PN, Boston RJ, James AN, Thompson LC, et al. (1998) Health-related quality of life in Australian men remaining disease-free after radical prostatectomy. Med J Aust 168: 483-486.

- Ammirati E, Polisini G, Giammò A (2025) Surgical treatment options and outcomes for concomitant treatment of post-prostatectomy erectile dysfunction and male stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Impot Res.

- Montague DK (2012) Artificial urinary sphincter: long-term results and patient satisfaction. Adv Urol 2012: 835290.

- Bettocchi C, Palumbo F, Spilotros M, Lucarelli G, Palazzo S, et al. (2010) Patient and partner satisfaction after AMS inflatable penile prosthesis implant. J Sex Med 7: 304-309.

- Bentellis I, El-Akri M, Cornu JN, Brierre T, Cousin T, et al. (2021) Prevalence and Risk Factors of Artificial Urinary Sphincter Revision in Nonneurological Male Patients. J Urol 206: 1248-1257.

- Sundaram V, Cordon BH, Hofer MD, Morey AF (2016) Is Risk of Artificial Urethral Sphincter Cuff Erosion Higher in Patients with Penile Prosthesis? J Sex Med 13: 1432-1437.

- Loh-Doyle JC, Ashrafi A, Nazemi A, Ghodoussipour S, Thompson E, et al. (2019) Dual Prosthetic Implantation After Radical Cystoprostatectomy and Neobladder: Outcomes of the Inflatable Penile Prosthesis and Artificial Urinary Sphincter in Bladder Cancer Survivors. Urology 127: 127-132.

- Wang R, McGuire EJ, He C, Faerber GJ, Latini JM (2012) Long-term outcomes after primary failures of artificial urinary sphincter implantation. Urology 79: 922-928.

- Chan EP, Punjani N, Campbell JD, Abed H, Brock G (2019) Indications for Penile Prosthesis Revision: Lessons Learned to Limit Technical Causes of Reoperation. J Sex Med 16: 1444-1450.

- Mirheydar H, Zhou T, Chang DC, Hsieh TC (2016) Reoperation Rates for Penile Prosthetic Surgery. J Sex Med 13: 129-133.

- Chierigo F, Capogrosso P, Dehò F, Pozzi E, Schifano N, et al. (2019) Long-Term Follow-Up After Penile Prosthesis Implantation-Survival and Quality of Life Outcomes. J Sex Med 16: 1827-1833.

- Miller LE, Khera M, Bhattacharyya S, Patel M, Nitschelm K, et al. (2022) Long-Term Survival Rates of Inflatable Penile Prostheses: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Urology 166: 6-10.

- Deruyver Y, Schillebeeckx C, Beels E, De Ridder D, Van der Aa F (2022) Long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction after artificial urinary sphincter implantation. World J Urol 40: 497-503.

- Radomski SB, Ruzhynsky V, Wallis CJD, Herschorn S (2018) Complications and Interventions in Patients with an Artificial Urinary Sphincter: Long-Term Results. J Urol 200: 1093-1098.

- Bayliss LE, Culliford D, Monk AP, Glyn-Jones S, Prieto-Alhambra D, et al. (2017) The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 389: 1424-1430.

- Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, et al. (2018) Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 391: 1023-1075.

- Huang MM, Huffman P, Dani H, Knijnik PG, da Silva AF, et al. (2022) Association between Previous Pelvic Radiation and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Failure of Replacement Artificial Urinary Sphincters. J Urol. 207: 1268-1275.

- O'Connor RC, Nanigian DK, Patel BN, Guralnick ML, Ellision LM, et al. (2007) Artificial urinary sphincter placement in elderly men. Urology 69: 126-128.

- Ziegelmann MJ, Linder BJ, Rivera ME, Viers BR, Rangel LJ, et al. (2016) Outcomes of artificial urinary sphincter placement in octogenarians. Int J Urol 23: 419-423.

- Chung E, Solomon M, DeYoung L, Brock GB (2014) Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction rates among elderly male aged ≥75 years with inflatable penile prosthesis implant for medically refractory erectile dysfunction. World J Urol 32: 173-177.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.