Reconstruction in Augmentation Mammoplasty Associated Breast Desmoid Fibromatosis

by Jonathan P. Yasmeh1, Andrew C. Hostler1, Hannah E. Korah1, Sahre Ozoplat2, Stephanie Worrell1, Jennifer Erdrich1, Kellen Chen1, Geoffrey C. Gurtner1, Aaron C. Mason1*

1Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Tucson, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA

2Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, Tucson, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA

*Corresponding author: Aaron C. Mason, MD, FACS, FAAP, Professor and Chief, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Clinical Professor, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, Tucson, University of Arizona, 1501 N. Campbell Ave, Room 4410 Tucson, AZ 85724, USA

Received Date: 08 January 2026

Accepted Date: 13 January 2026

Published Date: 15 January 2026

Citation: Yasmeh JP, Hostler AC, Korah HE, Ozoplat S, Worrell S, et al. (2026). Reconstruction in Augmentation Mammoplasty Associated Breast Desmoid Fibromatosis. Ann Case Report. 11: 2504. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102504

Abstract

Breast desmoid fibromatosis (BDF) is a rare, locally invasive neoplasm that predominantly affects females. Although BDF is typically benign, it can infiltrate the rib cage, necessitating invasive surgical resection and complex chest wall reconstruction. While there have been reported cases of BDF in association with silicone breast implants, cases requiring rib resection and chest wall reconstruction following augmentation mammoplasty are exceedingly rare. Here, we present two such cases and the reconstructive challenges involved. Two women, both under 30, developed invasive BDF within three years of bilateral subpectoral silicone breast augmentation. Both presented with rapidly enlarging chest wall masses detected through self-examination. Imaging revealed bulky, aggressive tumors infiltrating the pectoralis muscle and abutting the underlying ribs. In both cases, biopsies confirmed breast desmoid fibromatosis. Due to extensive chest wall involvement, surgical management included en bloc segmental rib resection and chest wall reconstruction with rib plating. Tissue expanders were placed as the first stage of breast reconstruction, preserving chest wall integrity and optimizing aesthetic outcomes. Given the rarity and infiltrative nature of BDF, early recognition and a multidisciplinary approach to surgical management are crucial. Surgeons should consider breast desmoid fibromatosis in the differential diagnosis of breast masses in patients with a history of silicone augmentation..

Keywords: Desmoid fibromatosis; Breast desmoid fibromatosis; Desmoid tumor; Augmentation mammoplasty; Reconstruction; Chest wall; Rib resection; Breast; Plastic surgery

Introduction

Desmoid fibromatosis (DF) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm, accounting for approximately 3% of soft tissue tumors in the United States and affecting about 1000-1200 people annually [1,2]. It is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 30-40 years and predominantly occurs in women [3,4]. While DF can be locally invasive, no evidence of metastatic potential has been documented [5]. Although tumor cells do not display malignant nuclear and cytoplasmic cell features, cells undergo clonal fibroblastic proliferation with diverse progression rates and an ability to infiltrate local tissues [6]. DF can be classified as either sporadic or non-sporadic. Non-sporadic DF accounts for approximately 1015% of cases and usually occurs in the mesentery in association with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) [7], a diagnosis that carries a 1000-fold higher risk of developing DF [8]. Sporadic DF, comprising 85% of cases, is commonly linked to mutations in the gene encoding the β-catenin transcription factor (CTNNB1) that encodes an inhibitor of β-catenin located upstream [9,10].

The anatomical location of the tumor often characterizes DF and is commonly designated as intraabdominal or extra-abdominal. Intraabdominal DF often develops in the mesentery or connective tissue surrounding the abdominal organs [11]. Extra-abdominal DF can present elsewhere but most commonly occurs in the limb, trunk, head, or neck [12]. In addition to genetic predispositions (i.e., FAP), high estrogen levels, previous surgery, and hormonal imbalances have also been shown to be associated with DF development [11,13]. The management of such tumors includes observation, active surveillance, radiation therapy, cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation, chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, anti-hormonal agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and surgical excision [7,14]. Determining the progression, stabilization, regression, or recurrence of the tumor can be challenging, thus treatment is case-specific. Recent consensus for treatment has transitioned from favoring surgical excision to observation or active surveillance as the first-line approach [15,16].

DF that occurs in the breast is an uncommon cause of a breast mass and is often mistaken as a primary breast malignancy. A prior series evaluating breast desmoid fibromatosis (BDF) observed that individuals who were diagnosed with BDF had a prior history of breast-related surgery and/or breast cancer [5]. A review in 2018 reported 36 cases of BDF associated with silicone breast implants [17]. There have been no reported cases requiring rib resection and chest wall reconstruction in a patient with previous augmentation mammoplasty. There has been one reported case requiring rib resection and chest wall reconstruction who had prior implantbased reconstruction [18]. In this manuscript, we present two cases of BDF following bilateral augmentation mammoplasty requiring rib resection and chest wall reconstruction.

Case 1:

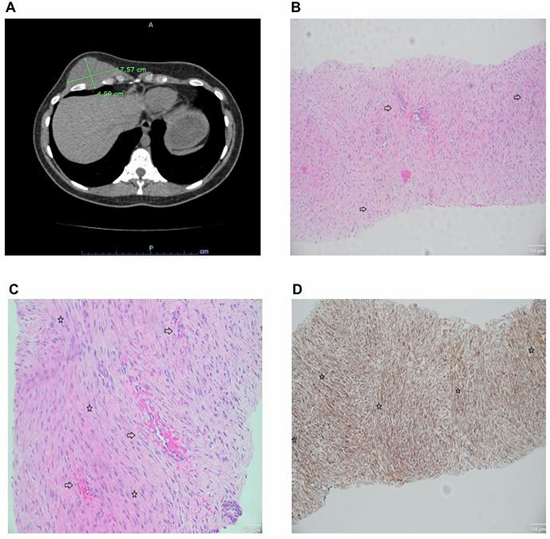

A 28-year-old female with a history of bilateral subpectoral silicone implants placed 3 years prior presented with an enlarging mass in the right chest wall under her breast. The patient first noticed the mass a year prior and endorsed progressive tenderness. Examination revealed a palpable 9 x 8 cm firm, fixed mass at the inframammary fold. The mass extended cephalad under the implant and caudad toward the subcostal margin but did not cross it. The mass effect of the tumor displaced the implant superiorly, resulting in breast asymmetry. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an intramuscular mass measuring 6.9 cm with the radiographic appearance of a BDF. Computerized tomography (CT) showed a right anterior chest wall mass infiltrating the anterior chest wall musculature, fifth intercostal space, and abutting the 5th and 6th ribs, measuring 7.5 x 4.6 cm (Figure 1A). Core needle biopsy showed neoplastic cells that were positive for beta-catenin (nuclear and cytoplasmic), focally positive for smooth muscle antibody (SMA), and negative for S100 and CD34, which demonstrated a pattern consistent with a diagnosis of desmoid fibromatosis (Figure 1B-D). Surgical oncology was consulted, followed by plastic surgery and thoracic surgery. A multidisciplinary surgical team recommended surgical resection due to the patient’s symptoms, rapid tumor growth with breast distortion, and local involvement of anatomical structures of the chest wall.

Figure 1: (A) A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest demonstrating a well-defined mass of the right anterior chest measuring 7.5 x 4.59 cm. The mass occupies the fifth intercostal space, extending between the fifth and sixth ribs, and infiltrates the anterior chest wall, invading the intercostal muscles. (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) image showing thinwalled blood vessels and intermittent vascular microhemorrhages (right arrowhead, ⇨). Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 µm. (C) Higher magnification H&E image showing microhemorrhages (right arrowhead, ⇨) and fascicular architecture (star, ⇨). Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 µm. (D) Representative immunohistochemical staining for nuclear beta-catenin (+) (β-catenin) demonstrating marked nuclear positivity and long sweeping fascicles (star, ⇨). Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 µm.

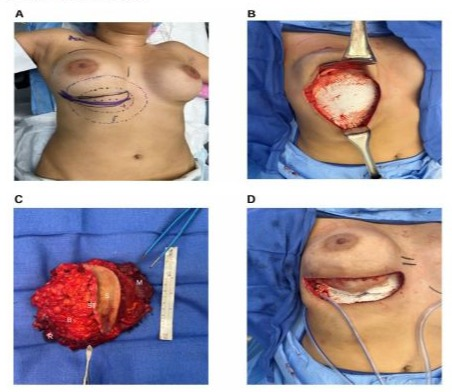

The prior breast implant was explanted and a full-thickness en bloc resection of the mass was performed including the overlying skin, subcutaneous tissue, breast parenchyma, muscle, implant capsule, and sections of involved ribs 4-8 (Figure 2A, B). The final specimen measured 15 x 15 x 7 cm (Figure 2C) and the margins were clear. Reconstruction involved 5th rib plating, which spanned the rib defect, and a 2 mm mesh that was fitted to the size of the defect. A breast tissue expander was placed, a drain was inserted, and the incisions were closed in multiple layers (Figure 2D). At end-expansion at 3 months postop, the tissue expander was removed, and a silicone breast implant was placed, restoring breast volume and contour.

Figure 2: (A) Macroscopic photo of the preoperative markings outlining the following: breast borders (purple overlaying line), surgical incision (solid black line), tumor margins (dotted and dashed black line), and resection margins (purple dotted and dashed line). (B) Intraoperative view of chest wall with overlying mesh after tumor resection. (C) Gross macroscopic image of an en bloc resected specimen of a breast desmoid fibromatosis (BDF) and adjacent tissues measuring 15 x 15 x 7 cm. S, skin; ST, subcutaneous tissue; B, breast parenchyma; M, muscle; R, rib. (D) Gross photo of reconstructed chest prior to closure with 5th rib plate spanning tumor gap, overlying Goretex mesh, and surgical drain.

Case 2:

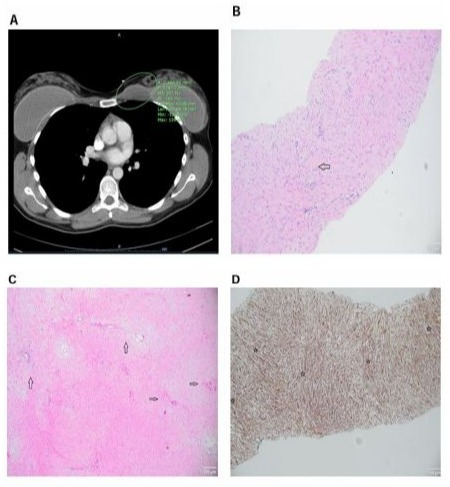

A 29-year-old female with bilateral 350cc subpectoral silicone implants placed one year prior presented with a rapidly enlarging lump near her left breast. She noted a mass in the superomedial chest that began as vaguely palpable but grew steadily to mass effect. The mass was tender. On physical exam, the upper left chest wall had a firm, fixed solid mass just beyond the superior margin of the implant. The mass measured 4.5 x 3.5 cm. A left breast ultrasound (US) demonstrated a 3.6 cm oval mass in the left breast surrounded by the pectoralis muscle. CT chest demonstrated a 4.8 cm mass at the medial aspect of the left anterior chest wall, abutting the medial superior aspect of the left breast implant (Figure 3A). Subsequent MRI showed a 5 x 2 x 3.7 cm mass within the pectoralis major muscle abutting the implant with characteristics suggesting a myxoid or possibly hemorrhagic component, suspicious for sarcoma. The patient underwent a US guided core needle biopsy that revealed bland spindle cell proliferation with delicate fibrous stroma, no atypia, only rare mitoses, and strong beta-catenin (Figure 3B-D). The morphologic and immunohistochemical features were characteristic of DF. After consultation with surgical oncology, plastic surgery, and thoracic surgery, surgical resection was recommended due to the patient’s persistent symptoms, rapid growth, distortion of the breast, and the appearance of chest wall invasion.

Figure 3: (A) A computerized tomography (CT) of the chest showing left anterior chest wall mass measuring 4.8 cm. The wellcircumscribed, homogenous mass abuts the left breast implant and is adjacent to the pectoral musculature. (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) image showing elongated, slender spindled cells arranged in a uniform stroma (left arrowhead, ⇨). The cells are pale with minimal nuclear atypia. Magnification 40x, scale bar 100 µm. (C) Higher magnification H&E image emphasizing characteristic spindle cells (right arrowhead, ⇨), long sweeping fascicles, as well as thin-walled blood vessels (upward arrowhead, ⇨). Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 µm. (D) Representative immunohistochemical staining for nuclear beta-catenin (+) (β-catenin). The spindle-shaped cells demonstrate nuclear β-catenin expression (star, ⇨). The image shows dense cellularity, with uniform fibroblastic proliferation. Magnification 10x, scale bar 100 µm.

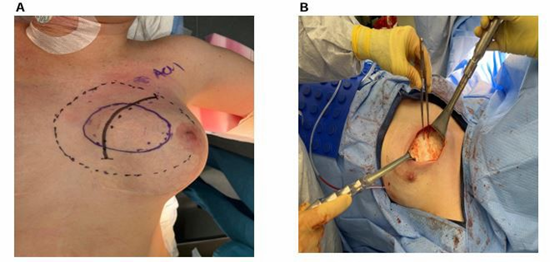

The implant was removed and a radical resection of the left chest wall desmoid tumor was performed en bloc with the pectoralis major muscle, segmental rib resection (ribs 2 and 3), and a portion of the sternum (Figure 4A, B). The specimen measured 15 x 11 x 4 cm and clean margins were achieved. Reconstruction involved rib plating, mesh placement, and insertion of a left breast tissue expander, which was later exchanged for a silicone implant after two months of expansion.

Figure 4 A: Preoperative surgical markings outlining the excision of the tumor located on the medial aspect of the left anterior chest wall. Shown are the planned surgical incision (solid black line), tumor margins (solid purple line), and resection margins (black dotted and dashed line). B: Intraoperative view of chest wall after surgical excision of a breast desmoid fibromatosis (BDF). Retractors used to provide optimal exposure, and the tumor bed is clearly visible with clean surgical margins.

Discussion

Breast desmoid fibromatosis (BDF) is especially rare, accounting for only 0.2% of breast tumors and 4% of extra-abdominal DF [17,19]. In addition to recognized risk factors for developing DF, an association between prior breast silicone implants and the development of BDF has been noted [20,21].

The fibrous capsule that results from the foreign body response has been proposed as a potential cause of BDF formation [22,23]. Establishing a registry that collects cases of breast implants and BDF might further inform a relationship between the two entities. While the etiology of the tumor is not known, the development of DF in patients with breast implants is uncommon. BDF is associated with implants in 10% of reported cases and usually occurs within 3 years of implant placement [17].

Outside of the treatment guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), guidance on clinical management of these patients is sparse. Notably, BDF can closely resemble the appearance of breast carcinoma or sarcoma with a dense, spiculated mass on radiological imaging [24-26]. Given the unique nature of BDF, management is often determined on an individual basis and may involve observation, surgical extirpation, radiotherapy, and systemic pharmacotherapy. A recently proposed algorithm for diagnosing BDF includes a focused clinical exam, imaging (mammography, ultrasound, or MRI), core needle biopsy, and discussion in a multidisciplinary conference [24]. Management depends on symptomatology: for minimal symptoms, active surveillance is recommended, while significant symptoms may warrant systemic therapy as the first line of treatment, with surgical resection as the second line [24]. However, lesions located in the anterior chest wall can cause significant morbidity given vital structures in the region. Therefore, many still advocate for upfront surgical resection of BDF compared to DF in other anatomical locations [27,28].

If surgical resection is selected, the primary goal should be to achieve clear margins. In cases where the margins are close, adjuvant radiotherapy should be considered. Following resection, the rate of recurrence is high. Duazo-Cassin et al. reported that 4 of 46 (8.7%) surgically resected BDF patients had a recurrence in a median follow-up of 24.9 months [29]. Managing recurrence can be particularly difficult. If other treatment options fail, further surgery may be considered. Patients should be surveilled every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years, then annually with MRI. Additionally, age-appropriate and patient-specific breast cancer screenings should continue.

Conclusion

In summary, breast desmoid fibromatosis is a rare lesion that can grow rapidly and lead to notable functional and aesthetic concerns. Early recognition with appropriate diagnosis is important in treatment planning. A more conservative approach is preferred in recent years due to the high morbidity associated with the procedure. However, when the tumor has invaded the chest wall, surgical intervention is recommended. Definitive management should be led by a multispecialty surgical team that considers both extirpated and reconstructive options in surgical planning to mitigate the possibility of recurrence and optimize aesthetic and reconstructive options.

Financial Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial disclosures, conflicts of interest, or relevant product affiliations to declare.

References

- Prendergast K, Kryeziu S, Crago AM. (2022). The Evolving Management of Desmoid Fibromatosis. Surg Clin North Am; 102: 667677.

- Crago AM, Chmielecki J, Rosenberg M. (2015). Near universal detection of alterations in CTNNB1 and Wnt pathway regulators in desmoid-type fibromatosis by whole-exome sequencing and genomic analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 54: 606-615.

- Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J. (2017). An update on the management of sporadic desmoid type fibromatosis: a European Consensus Initiative between Sarcoma PAtients EuroNet (SPAEN) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG). Ann Oncol. 28: 2399-2408.

- van Broekhoven DL, Grünhagen DJ, den Bakker MA, van Dalen T, Verhoef C. (2015). Time trends in the incidence and treatment of extraabdominal and abdominal aggressive fibromatosis: a populationbased study. Ann Surg Oncol. 22: 2817-2823.

- Berri RN, Baumann DP, Madewell JE, Lazar A, Pollock RE. (2011). Desmoid tumor: current multidisciplinary approaches. Ann Plast Surg. 67: 551-564.

- Skubitz KM. (2017). Biology and Treatment of Aggressive Fibromatosis or Desmoid Tumor. Mayo Clin Proc. 92: 947-964.

- Ratan R, Roland CL, Bishop AJ. (2021). Desmoid Fibromatosis: Management in an Era of Increasing Options. Curr Oncol Rep. 23: 41.

- Garcia-Ortega DY, Martín-Tellez KS, Cuellar-Hubbe M. (2021). Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis. Cancers (Basel). 12.

- Alman BA, Li C, Pajerski ME, Diaz-Cano S, Wolfe HJ. (1997). Increased beta-catenin protein and somatic APC mutations in sporadic aggressive fibromatoses (desmoid tumors). Am J Pathol. 151: 329334.

- Couture J, Mitri A, Lagace R. (2000). A germline mutation at the extreme 3’ end of the APC gene results in a severe desmoid phenotype and is associated with overexpression of beta-catenin in the desmoid tumor. Clin Genet. 57: 205-212.

- Bektas M, Bell T, Khan S. (2023). Desmoid Tumors: A Comprehensive Review. Adv Ther. 40: 3697-3722.

- Eastley N, McCulloch T, Esler C. (2016). Extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis: A review of management, current guidance and unanswered questions. Eur J Surg Oncol. 42: 1071-1083.

- Riedel RF, Agulnik M. (2022). Evolving strategies for management of desmoid tumor. Cancer. 128: 3027-3040.

- Martínez Trufero J, Pajares Bernad I, Torres Ramón I, Hernando Cubero J, Pazo Cid R. (2017). Desmoid-Type Fibromatosis: Who, When, and How to Treat. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 18: 29.

- Otero S, Moskovic EC, Strauss DC. (2015). Desmoid-type fibromatosis. Clin Radiol. 70: 1038-1045.

- Spolverato G, Capelli G, Kasper B, Gounder M. (2022). Management of Desmoid Tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 31: 447-458.

- Tzur R, Silberstein E, Krieger Y, Shoham Y, Rafaeli Y. (2018). Desmoid Tumor and Silicone Breast Implant Surgery: Is There Really a Connection? A Literature Review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 42: 59-63.

- Kilmartin C, Westover C, Raghavan S, Dillon PM, Campbell CA. (2023). Desmoid Tumor and Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction. Case Rep Oncol. 16: 74-80.

- Taylor TV, Sosa J. (2011). Bilateral breast fibromatosis: case report and review of the literature. J Surg Educ. 68: 320-325.

- Neuman HB, Brogi E, Ebrahim A, Brennan MF, Van Zee KJ. (2008). Desmoid tumors (fibromatoses) of the breast: a 25-year experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 15: 274-80.

- Erguvan-Dogan B, Dempsey PJ, Ayyar G, Gilcrease MZ. (2005). Primary desmoid tumor (extraabdominal fibromatosis) of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 185: 488-489.

- Jewett ST, Jr., Mead JH. (1979). Extra-abdominal desmoid arising from a capsule around a silicone breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 63: 577-579.

- Schuh ME, Radford DM. (1994). Desmoid tumor of the breast following augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 93: 603-605.

- Kangas-Dick A, Ali M, Poss M, Khoury T, Takabe K. (2024). Diagnosis and Management of Desmoid Fibromatosis of the Breast. World J Oncol. 15: 394-404.

- Povoski SP, Jimenez RE. (2006). Fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) of the breast mimicking a case of ipsilateral metachronous breast cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 4: 57.

- Ng WL, Teoh SY, See MH. (2021). Desmoid Type Fibromatosis of the Breast Masquerading as Breast Carcinoma: Value of Dynamic Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Its Correlation. Eur J Breast Health. 17: 197-199.

- Scheer L, Lodi M, Molière S, Kurtz JE, Mathelin C. (2017). Medical treatment of mammary desmoid-type fibromatosis: which benefit? World J Surg Oncol. 15: 86.

- Liu H, Zeng H, Zhang H. (2020). Breast fibromatosis: Imaging and clinical findings. Breast J. 26: 2217-2222.

- Duazo-Cassin L, Le Guellec S, Lusque A. (2019). Breast desmoid tumor management in France: toward a new strategy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 176: 329-335.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.