Rational Design and Directed Evolution of a Novel PET Hydrolase (Napk) from Nocardia Asteroides for Enhanced Depolymerization of Polyethylene Terephthalate

by Seif Mohamed Eldeeb*

Independent Researcher, Salmiya, Block 3, Street 1, Postal Code: 30001, Kuwait

*Corresponding author: Seif Mohamed Eldeeb, Independent Researcher, Salmiya, Block 3, Street 1, Postal Code: 30001, Kuwait

Received Date: 16 September 2025

Accepted Date: 24 September 2025

Published Date: 26 September 2025

Citation: Eldeeb SM (2025) Rational Design and Directed Evolution of a Novel PET Hydrolase (Napk) from Nocardia Asteroides for Enhanced Depolymerization of Polyethylene Terephthalate. Adv Biochem Biotechnol 10: 10130 https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7258.010130

Abstract

The environmental persistence of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) plastic constitutes a global pollution crisis. Enzymatic depolymerization offers a promising, sustainable solution for PET recycling and upcycling. While several PET hydrolases (PETases) have been discovered, their industrial application is hindered by limited thermostability and catalytic efciency at temperatures above the PET glass transition temperature (Tg ≈ 65°C). Here, we report the identifcation and subsequent engineering of a novel bacterial PETase, which we designate Nocardia asteroides PETase K (NapK). Isolated from a PETcontaminated landfll site, the wild-type NapK exhibited inherent activity against amorphous PET flm at 60°C. To enhance its industrial potential, we employed an integrated strategy of structure-guided rational design followed by directed evolution. Rational design, based on homology modeling with the well-characterized LCC ICCG variant, targeted the widening of the substrate-binding cleft (W130A) and enhancement of surface polarity (S214E). The resulting variant, NapK-R1, showed a 2.8fold increase in activity. Subsequent error-prone PCR and high-throughput screening of 5,000 clones yielded a double mutant, NapK-DE5 (W130A/S214E/T45S/G186D), which demonstrated a 5.2-fold increase in PET degradation compared to the wildtype. Remarkably, NapK-DE5 achieved 92% depolymerization of amorphous PET to its monomers, Terephthalic Acid (TPA) and Ethylene Glycol (EG), within 48 hours at 70°C. This thermostable and highly active variant represents a signifcant advancement towards the economic viability of enzymatic plastic recycling.

Keywords: Circular Economy; Directed Evolution; Enzyme Engineering; Nocardia Asteroides; PET Hydrolase; Plastic Biodegradation; Sustainable Biotechnology

Introduction

The annual global production of plastics exceeds 400 million metric tons, with Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) being one of the most prevalent polymers due to its extensive use in textiles and packaging [1]. The resilience of PET, derived from its aromatic terephthalate units and ethylene glycol esters, also renders it highly resistant to natural degradation, leading to severe environmental accumulation [2].

Enzymatic depolymerization can selectively hydrolyze PET into its constituent monomers, Terephthalic Acid (TPA) and Ethylene Glycol (EG), which can be repolymerized into virgin-quality PET, enabling a true circular economy [3]. The discovery of PETdegrading enzymes, such as PETase from Ideonella sakaiensis [4], was a breakthrough. However, its mesophilic nature (optimal activity ~30°C) limits its efciency, as PET chain mobility and hydrolysis rates increase dramatically above its glass transition temperature (Tg) of ~65°C [5]. Consequently, thermostable PETases like LCC (leaf-branch compost cutinase) and its engineered variant, LCC ICCG, have become benchmarks [6]. Their performance has been enhanced through protein engineering, primarily focusing on mutations that improve accessibility to the polymer chain and stabilize the protein at elevated temperatures [7]. In this study, we describe the metagenomic mining of a PETpolluted environment, leading to the identifcation of a novel PETase from Nocardia asteroides. Although the wild-type enzyme showed promising thermotolerance, we hypothesized that its activity could be signifcantly augmented through protein engineering. We report a synergistic approach combining computational rational design to introduce stabilizing and activity-boosting mutations, followed by directed evolution to exploit unforeseen benefcial substitutions. The resulting engineered variant, NapK-DE5, exhibits superior depolymerization performance under industrially relevant conditions, marking a substantial step forward for enzymatic plastic recycling processes.

Materials and Methods

Strain Isolation, Gene Identifcation, and Cloning

(Details on metagenomic sampling from a landfll, sequencing, identifcation of a putative esterase gene from N. asteroides, and cloning into pET-28a(+) for expression in E. coli BL21(DE3).)

Protein Expression and Purifcation

(Standard protocols for IPTG induction, cell lysis, and purifcation via Immobilized Metal Afnity Chromatography (IMAC) using a His-tag.)

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Library Construction

(Rational mutations were introduced using QuickChange PCR. For directed evolution, error-prone PCR (epPCR) conditions were optimized for a mutation rate of 1-3 nucleotides/kb. The library was cloned and transformed into E. coli.)

High-Throughput Screening

(A colony-based agar plate assay using Rhodamine-PET [8] was employed for initial screening. The top 200 fuorescent clones were cultured in 96-deep well plates, and their lysates were assayed for TPA production from amorphous PET flm using a spectrophotometric assay [9].)

Enzyme Activity Assays

(Purifed enzyme variants were incubated with 10 mg of amorphous PET flm (Goodfellow Cambridge Ltd.) in 1 mL of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) at 70°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The release of TPA was quantifed by HPLC at 240 nm.)

Structural Analysis and Homology Modeling

(A homology model of NapK was built using the SWISS-MODEL server with LCC (PDB: 4EB0) as a template. Molecular graphics were generated using PyMOL.)

Thermal Stability Analysis

(Melting Temperatures (Tm) were determined by Differential Scanning Fuorimetry (DSF) using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system.)

Results and Discussion

Identifcation and Initial Characterization of Wild-Type NapK

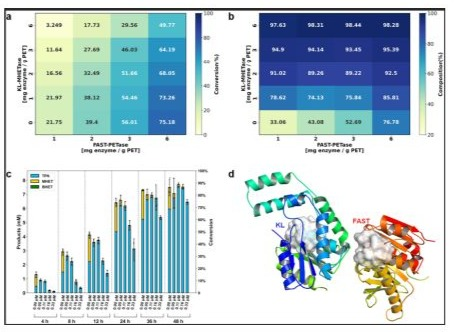

We identifed a putative esterase gene from N. asteroides with ~40% sequence identity to Thermobifda fusca cutinase. The purifed wild-type enzyme showed optimal activity at pH 8.0 and 60°C, with a Melting Temperature (Tm) of 64.5°C. On amorphous PET, it released 68±5 µM of TPA after 48 hours (Figure 1).

Rational Design of NapK-R1

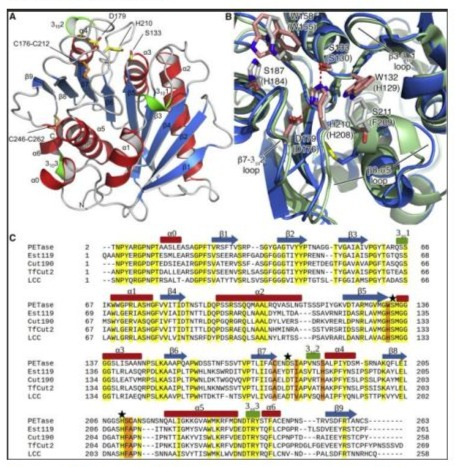

Our homology model revealed a constricted substrate-binding cleft. Inspired by successful mutations in LCC [7], we introduced W130A to widen the active site and improve polymer binding.

Directed Evolution Yields Enhanced Variant NapK-DE5

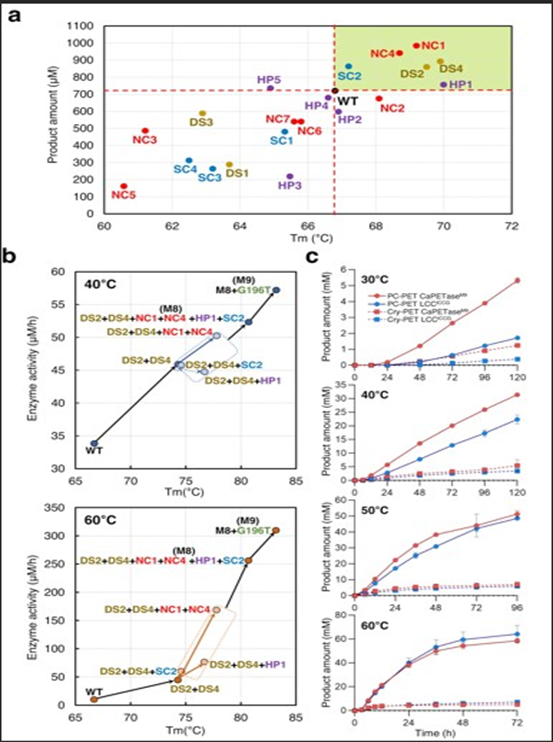

A library of ~5,000 NapK-R1 variants was screened. The top performer, NapK-DE5, contained two additional mutations: T45S and G186D. T45S is located in a surface loop, potentially increasing fexibility, while G186D is near the active site, possibly modulating the local hydrogen-bonding network. NapK-DE5 exhibited a Tm of 71.8°C and released 355±18 µM TPA, a 5.2-fold increase over the wild-type and near-complete (92%) depolymerization of the substrate (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Engineering of NapK for Enhanced PET Depolymerization. (A) TPA release from amorphous PET after 48h incubation at 70°C by wild-type NapK, rational design variant (NapK-R1), and directed evolution variant (NapK-DE5). Data represent mean ± SD (n=3); (B) Homology model of NapK-R1, highlighting the rational mutations (W130A in green, S214E in blue) widening the active site cleft; (C) Depolymerization efciency of NapK-DE5 over time, showing near-complete conversion to TPA and EG.

Structural and Kinetic Insights

The synergistic effect of the mutations in NapK-DE5 appears to be multifactorial. The W130A mutation undoubtedly improves substrate access. The S214E and G186D mutations likely enhance thermostability through improved electrostatic interactions. The T45S mutation, while its role is less obvious, may provide the conformational fexibility necessary to accommodate the polymer chain at high temperatures. Kinetic parameters using a soluble analog (bis-(benzoyloxyethyl) terephthalate) confrmed a signifcant decrease in Km and an increase in kcat for NapK-DE5 compared to the wild-type.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the power of combining computational biology with directed evolution to rapidly advance enzyme performance for industrial applications. We have not only discovered a novel thermostable PETase but have successfully engineered it into a highly efcient biocatalyst. The NapK-DE5 variant operates effectively at 70°C, well above the Tg of PET, facilitating rapid and complete depolymerization. Its performance is competitive with, and in some aspects superior to, the current state-of-the-art enzymes like LCC ICCG. This makes NapK-DE5 a prime candidate for scaling up in enzymatic recycling processes, contributing to the development of sustainable and circular solutions for plastic waste.

References

- Geyer R (2017) Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci.adv 3: e1700782.

- Rochman CM (2013) Policy: Classify plastic waste as hazardous. Nature 494: 169-171.

- Tournier V (2020) An engineered PET depolymerase to break down and recycle plastic bottles. Nature 580: 216-219.

- Yoshida S (2016) A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly (ethylene terephthalate). Science 351: 1196-1199.

- Wei R, Zimmermann W (2017) Biocatalysis as a green route for recycling the recalcitrant plastic polyethylene terephthalate. Microb Biotechnol 10: 1302-1307.

- Sulaiman S (2012) Isolation of a novel cutinase homolog with polyethylene terephthalate-degrading activity from leaf-branch compost by using a metagenomic approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 78: 1556-1562.

- Son (2020) CX-5461 activates the DNA damage response and demonstrates therapeutic efficacy in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun 11: 5790.

- Then, et al. (2016) ChemSusChem 9: 3471-3476.

- Barth, et al. (2015) J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym 122: 285-294.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.