Radical Hysterectomy: A Retrospective Review of 85 Cases as Salvage Therapy for Persistent or Recurrent Cervical Cancer after Radiation and Chemoradiation

by Alfonso Torres-Lobatón1*, Rosalva Barra-Martínez2, María Yicel Bautista-Hernández3,Juan Carlos Oliva-Posada4, Fred Morgan-Ortiz5, Christian Molina-Aguilar6, Mauricio Durán-Cruz7, Fernando Ulises Lara-González8, Miguel Angel Rodríguez-José9, Thania Castro-Belio10

1Surgeon Oncologist, Oncology Gynecology Unit, Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, Prof of Gynecology Oncology Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico. México City, México

2Surgeon Oncologist, Master of Science, Head of Unit of Skin Cancer / Melanomas / Soft Tissue Sarcomas and Bone tumours, Oncology Service, Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

3Head of the Radiotherapy Unit, Oncology Service, Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

4Head Surgeon Oncologist of the Oncological Gynaecology Service Hospital General de México. “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

5Obstetrician gynaecologist, Master of Science, Health Sciences Research Center, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, México, México

6Laboratorio Internacional de Investigación sobre el Genoma Humano, México

7Radio oncologist, Radiooncology Unit. Oncology Service Hospital General de México. “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

8Surgeon Oncologist, Gynaecology Unit, Oncology Service Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

9Surgeon Oncologist, Gynaecology Unit, Oncology Service Hospital General de México “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

10Gynaecologist and Oncologist, Oncology Service Hospital General de México. “Dr. Eduardo Liceaga”, México City, México

*Corresponding author: Alfonso Torres Lobaton, Durango 50 bis Col Roma CP06700 Ciudad de México. México

Received Date: 5 December 2024

Accepted Date: 09 December 2024

Published Date: 11 December 2024

Citation: Torres-Lobatón A, Barra-Martínez R, Bautista-Hernández MY, Oliva-Posada JC, Morgan-Ortiz F, et al. (2024) Radical Hysterectomy: A Retrospective Review of 85 Cases as Salvage Therapy for Persistent or Recurrent Cervical Cancer after Radiation and Chemoradiation. Ann Case Report. 9: 2112. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102112

Abstract

Background: Radical hysterectomy (RH) is not considered in the bibliography as salvage therapy for persistent or recurrent cervical cancer (CC) after radiation (RT) and chemoradiation (CCRT). We evaluate the outcomes of 85 (RH) performed as salvage surgery for (CC) based on a 51-year institutional experience. Methods: A retrospective study was conducted on CC patient records from the Oncology Service of the Hospital General de México, who underwent RH between 1966 and 1979 (earlier period) and from 1980-2006 to 2008-2018 (later period). Results: The median age was 46.4 years. Of the patients, 50.5% received RT and 49.4% received CCRT. Major postoperative complications occurred in 28.2% of patients, with a significant decrease in the later study period (17.1%). Four postoperative deaths (4.7%) were reported, all occurring in the earlier period. Overall survival was 54.1% with a median follow-up of 34.1 months. Similarly, overall survival was significantly better for patients who received CCRT (p=0.013,) and had smaller tumors (p=0.038). Multivariate analysis showed that tumor size less than 3 cm was the only significant predictor of overall survival (p=0.014). Conclusion: In this series, overall survival was 54.1%. Major complications decreased significantly over time, and there were no postoperative deaths in the later study period. RH may be considered for tumors measuring 3 cm or less.

Keywords: Radical hysterectomy; Cervical cancer; Post-radiation; Chemoradiation

Abbreviations: (AC): Adenocarcinoma; (CC): Cervical Cancer; (CCPR): Cervical Cancer Persistent or Recurrent; (CCRT): Concomitant Chemoradiation; (DFS): Disease Free Survival; (EBRTCT) External beam radiotherapy/Chemotherapy;(ESGO) European Society ofGynecological Oncology; (FIGO):International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; (GC): Gynecological Cancer ;(GHM) General Hospital of Mexico; (Gy): Radiation treatment unit; (MC), Mayor Complications; (NCCN) National Comprehensive Cancer Network; (OU): Oncology Unit; (OS): Overall Survival; (PC): Postoperative Complications; (PE) Pelvic exenterations; (PET): Positron Emission Tomography;(RTA): Residual Tumor Activity; (SCC) Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) remains a significant public health problem in developing countries, often presenting at advanced stages and accounting for a large proportion of gynecologic cancer deaths [1-3]. In 2022, the World Health Organization estimated 111,200 new cancer cases in women in Mexico, of which 21,609 (19.4%) occurred in the genital tract, with CC being the most common gynecologic cancer with 10,348 new cases and 4,909 deaths [4].

In Mexican institutions such as the National Cancer Institute and the General Hospital of Mexico [5,6], CC is only surpassed by breast cancer in terms of incidence. Advanced stages predominate in CC, for which the treatment is a combination of external beam pelvic radiotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy based on platinum regimens, and brachytherapy for the central lesion (CCRT) [1,7]. Since 1999, following recommendations from the National Cancer Institute of the United States (NCCN), this treatment regimen has replaced the traditional radiotherapy scheme based on external beam radiotherapy followed by brachytherapy (RT) [1,3,7].

Although the CCRT scheme [1, 3,7] and rescue radical surgery in selected irradiated patients with central tumor persistence or recurrence remains valid for the management of advanced CC, recent publications refer to pelvic exenterations (PE) only as surgeries of choice, because of the high morbidity after Radical Hysterectomy (RH) when used in these patients [1,3,8,9].

As a salvage surgery in patients with recurrent CC after RT or CCRT, RH is a procedure on which we have little information in the literature. In 1993 Magrina FJ [9] published an article reviewing a total of 203 such procedures performed [10-13] over 54 years (1930-1984). The author concluded that this surgery was associated with high morbidity and mortality as a result of complications, related to the development of fistulas, which require colostomies or pelvic exenterations (PE).

The present article describes the experience of the Oncology Unit (OU) within the General Hospital of Mexico – Dr. Eduardo Liceaga (GHM). It includes 85 cases of Radical Hysterectomy as salvage surgery, in patients with persistent or recurrent CC after RT or CCRT, over a period of 51 years. Fifty of these cases [13] were included in the report on the 203 RH procedures, published in 1987 by Rubin CS et al of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center New York [10].

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of patient records was conducted from January 1, 1966, to December 31, 1979(earlier period), and from January 1, 1980 to December 31, 2006 and from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2018 (later period), involving 1,082 laparotomies performed in the Oncology Unit of the General Hospital of Mexico (GHM) on patients with persistent or recurrent(CC) following (RT) (50 Gy teletherapy followed by intracavitary radiotherapy, brachytherapy 30 Gy) and/or concomitant chemotherapy with platinum or carboplatin (CCRT). Patients were included if they had optimal functional reserve and tumor confined to the cervix and/or vagina, based on clinical examination and imaging studies.

Following bowel preparation, a midline supra- and infraumbilical laparotomy was performed, and the abdominal and pelvic cavities were explored. If suspicious abdominal disease was identified, an intraoperative biopsy was obtained, followed by pelvic lymph node dissection. If the biopsy confirmed metastatic disease, the procedure was terminated. Otherwise, a complete pelvic lymph node dissection was performed. During the period from 1966 to 1979 (earlier period), pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed according to the criteria of JV Meigs [14], dissecting the anterior branches of the hypogastric plexus to the middle hemorrhoidal vessels (Figure 1). In subsequent periods, the procedures were primarily based on the technique described by Piver and Rutledge [15], preserving these branches. The specimen was removed in bloc with adequate vaginal margins and a Penrose drain was placed in the surgical bed. The drain was removed within 3 days postoperatively. The Foley catheter was removed after the second postoperative week if residual urine in the bladder was less than 100 ml. Urinary dysfunction lasting 3 months or longer was considered a major complication.

Figure 1: Pelvic lymphadenectomy and surgical bed in 50 radical hysterectomies performed in the period 1966-1979.

For the purpose of analysis, the evaluation of postoperative morbidity and mortality was divided into two periods: the first from 1966 to 1979 (earlier period), and the second from 1980 to 2006 and 2008 to 2018 (later period). Records from 2007 were lost due to archival remodeling.

Postoperative mortality was defined as death within the first 30 days of surgery, and major complications included pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, urinary dysfunction lasting more than 3 months, and vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas requiring urinary diversion or permanent colostomy [1, 3, 8, 9], as well as ureterovaginal fistulas, intestinal anastomotic dehiscence, and bowel obstruction. The FIGO 2018 staging system [1] was used, with stage I defined as IB2-B3 and stage III as IIIA and IIIB.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data, including means and proportions for numerical and categorical variables, respectively. Survival analysis was performed using the KaplanMeier method. Differences between groups were evaluated using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify variables associated with disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated for the hazard ratio, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0

Results

The 1,082 patients who underwent laparotomy during the 51-year study period, 85 cases (7.8%) underwent radical hysterectomy (RH) (Table 1). The youngest patient was 21 years old and the oldest was 65. The median age was 46.4 years. The most common histopathological type was squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (72.9% of cases), and most of patients (82.3%) were diagnosed at an advanced stage. Additionally, 50.6% received a complete pelvic cycle of radiotherapy (RT) as initial treatment (Table 2).

|

Surgeries |

Períods |

|||||

|

1966-1979 |

1980-2006 and 2008-2018 |

Number of cases |

||||

|

351 cases |

731 cases |

1082 |

||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

|

Laparotomies |

130 |

37 |

387 |

52.9 |

517 |

47.7 |

|

Exenterations |

171 |

48.7 |

309 |

42.2 |

480 |

44.3 |

|

Radical Hysterectomies |

50 |

14.2 |

35 |

4.7 |

85 |

7.8 |

|

Total |

351 |

100 |

731 |

100 |

1082 |

100 |

Table 1: Surgeries performed during the different periods.

Rescue surgeries, 565: Pelvic Exenterations, 480 (84.9 %) Radical Hysterectomies:85 (15.0%).

|

Variable |

n |

% |

|

Age (years)* |

||

|

21-30 |

2 |

2.4 |

|

31-40 |

21 |

25 |

|

41-50 |

36 |

42 |

|

51-60 |

22 |

26 |

|

> 60 |

4 |

4.7 |

|

Clinical Stage |

||

|

IB |

12 |

14 |

|

IIA y IIB |

46 |

54 |

|

IIIA y IIIB |

24 |

28 |

|

Not Classified |

3 |

3.5 |

|

Histological type |

||

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

62 |

73 |

|

Adenocarcinoma |

23 |

27 |

|

Previous treatment |

||

|

Pelvic cycle of Radiotherapy |

43 |

51 |

|

Radiotherapy plus Chemotherapy |

34 |

40 |

|

Teletherapy plus Chemotherapy |

8 |

9.4 |

|

Tumor size |

||

|

Tumor < 3 cm |

69 |

81 |

|

Tumor 3 cm or > |

16 |

18 |

|

*Median age: 46.4 years. |

||

Table 2: Descriptive analysis of 85 cases of radical hysterectomy.

Morbidity and Mortality: Major postoperative complications occurred in 24 of the 85 patients (28.2%). This included 18 of the 50 patients in the earlier period from 1966 to 1979 (36.0%) and 6 of the 35 patients in the later period from 1980 to 2018 (17.1%). Complications included 8 vesicovaginal fistulas, 6 ureterovaginal fistulas, 6 rectovaginal fistulas, 2 cases of pneumonia, 1 case of bowel obstruction, and one case of severe urinary dysfunction (Table 3). Five of the 8 patients who developed vesicovaginal fistulas underwent urinary diversion, while 3 refused treatment. Two of the 6 patients with ureterovaginal fistulas underwent ureteroneocystostomy, one had a nephrostomy, and one was managed conservatively with a double-J stent. Two of these 6 patients died from sepsis. Five of the 6 patients who developed rectovaginal fistulas underwent permanent colostomy, and the last patient declined intestinal diversion. The two patients who developed pneumonia died postoperatively, and the patient with bowel obstruction, as well as the patient with urinary dysfunction, were managed conservatively. All four deaths (4.7%) occurred in the group of patients operated on between 1966 and 1979.

|

Complication |

n |

% |

|

Vesicovaginal fistula |

8 |

9.4 |

|

Ureterovaginal fistula |

6 |

7 |

|

Rectovaginal fistula |

6 |

7 |

|

Bronchopneumonia |

2 |

2.3 |

|

Intestinal obstruction |

1 |

1.1 |

|

Bladder dysfunction |

1 |

1.1 |

|

Total |

24/85 |

28 |

|

*Eighteen of the 50 cases (36%) in the 1966-1979 seriedeveloped major complications vs 6/35 (17.1%) in the 1980-2018 series |

||

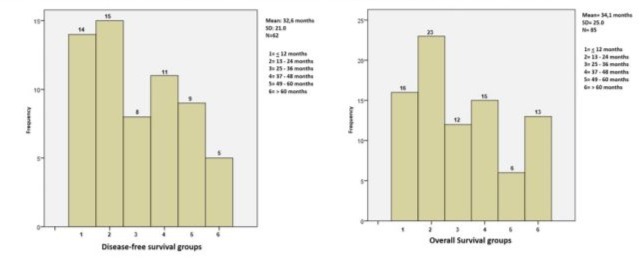

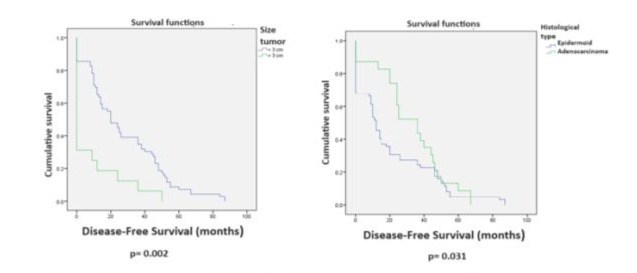

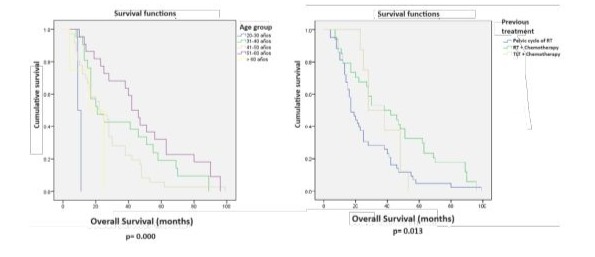

Table 3: Major complications in 85 patients*

Surgical Outcomes: Disease-free survival (DFS) of 25-72 months was achieved in 33/62 patients (53.2%) with a median follow-up of 32.3 months for these 62 cases. Overall survival (OS) for all 85 cases was 54.1% with a median follow-up of 34.1 months (Figure 2). Twenty-one of the 85 cases (24.7%) died from tumor recurrence, and follow-up data was lost for 2 patients (2.3%). Univariate analysis for DFS in the 85 radical hysterectomies showed statistically significant differences for the following variables: adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma (p=0.031), prior treatment with CCRT versus RT (p=0.001), tumor size less than 3 cm versus greater than 3 cm (p=0.002), and absence versus presence of nodal metastases (p=0.034). (Table 4, Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2. DFS from 25-72 months in 62 patients: 53.2% and, OS25-72 months in 85 patients: 54.1%.

Figure 3. Log-rank test for DFS in 85 patients with radical hysterectomies.

Figure 4. Log-rank test for DFS in 85 patients with radical hysterectomies.

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

P value |

|

Age group |

0.188 |

||

|

21-30 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

31-40 |

25.48 |

29.75 |

|

|

41-50 |

20.42 |

20.15 |

|

|

51-60 |

31.59 |

21.05 |

|

|

> 60 |

14.5 |

10.5 |

|

|

Clinical stage |

0.07 |

||

|

IB |

36.92 |

34.69 |

|

|

IIA -IIB |

22.39 |

19.26 |

|

|

IIIA – IIIB |

17.96 |

21.35 |

|

|

Not Classified |

39.67 |

18.77 |

|

|

Histological type |

0.031 |

||

|

Squamous cell carcinoma |

20.53 |

23.61 |

|

|

Adenocarcinoma |

32.61 |

19.53 |

|

|

Previous treament |

0.001 |

||

|

Pelvic cycle of radiotherapy |

14.6 |

19.15 |

|

|

CCRT |

32.8 |

25.35 |

|

|

EBRTCT |

14.2 |

11.78 |

|

|

Tumor size |

0.002 |

||

|

< 3 cm |

27.6 |

(+22.9) |

|

|

3 cm or > |

8.1 |

(+15.3) |

|

|

Lymph node metastasis |

0.034 |

||

|

No |

26.04 |

22.73 |

|

|

Yes |

11.38 |

22 |

|

|

SD: Standard Deviation |

|||

Table 4: Univariate analysis of disease-free survival (DFS) for different variables in 85 cases of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer.

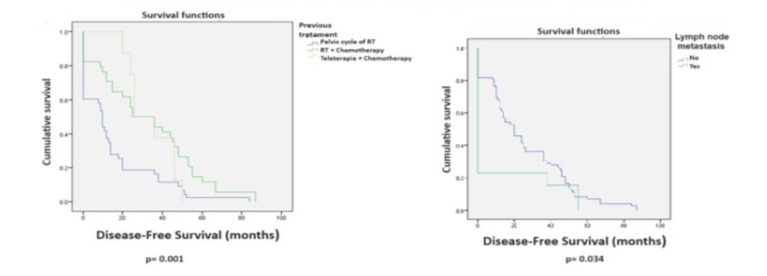

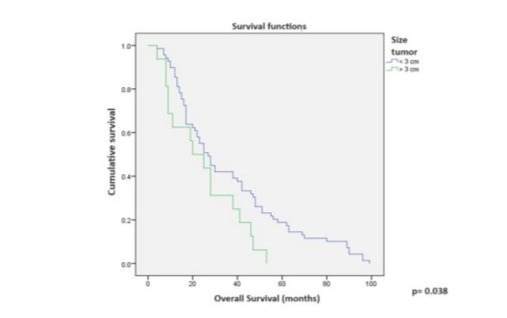

Multivariate Cox regression analysis for variables with significant DFS did not show significant differences. The closest was the type of radiotherapy, favoring CCRT (p=0.065) (Table 5). Univariate analysis for OS showed significant differences favoring the following variables: age 51-60 years (p=0.005), prior treatment with CCRT versus RT (p=0.013), and tumor size less than 3 cm (p=0.038) (Table 6, Figures 5 and 6). Multivariate Cox regression analysis for OS showed that only tumors 3 cm or smaller were a significant variable (p=0.014) (Table 7).

Figure 5. Log-rank test for OSin 85 patients with radical hysterectomies.

Figure 6. Log-rank test for OS in 85 patients with radical hysterectomies.

|

Variable included in the model |

B |

SE |

Wald |

OR |

P value |

|

(CI 95%) |

|||||

|

Histological type |

0.03 |

0.33 |

0.008 |

.538-1.972 |

0.928 |

|

Previous treatment |

-0.47 |

0.26 |

3.398 |

.377-1.030 |

0.065 |

|

Size tumor |

0.586 |

0.57 |

1.046 |

.585-5.515 |

0.306 |

|

Lymph node metastasis |

-0.59 |

0.6 |

0.971 |

.171-1.793 |

0.324 |

Table 5: Multivariate analysis of disease-free survival (DFS) for different variables in 85 cases of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer (Cox Regression).

Only variables that were statistically significant in the univariate were analyzed in multivariate Cox regression models.

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

P value |

|

Age group |

0.005 |

||

|

20-30 |

10 |

1.41 |

|

|

31-40 |

36.33 |

26.42 |

|

|

41-50 |

27.06 |

19.62 |

|

|

51-60 |

48.73 |

27.71 |

|

|

> 60 |

17.5 |

9.95 |

|

|

Clinical stage |

0.126 |

||

|

IB |

46.42 |

28.39 |

|

|

IIA – IIB |

31.09 |

18.51 |

|

|

IIIA – IIIB |

31.29 |

31.76 |

|

|

Not Classified |

53.67 |

28.74 |

|

|

Histological type |

0.365 |

||

|

Epidermoid |

32.6 |

27.34 |

|

|

Adenocarcinoma |

38.17 |

17.32 |

|

|

Previous treament |

0.013 |

||

|

Pelvic cycle of radiotherapy |

26.09 |

20.45 |

|

|

RT+CT |

43.71 |

29.25 |

|

|

TLT+CT |

36.37 |

11.94 |

|

|

Lymph node metastasis |

0.282 |

||

|

No |

39.71 |

25.687 |

|

|

Yes |

56 |

12.124 |

|

|

Overal survival and tumor size |

0.038 |

||

|

< 3 cm |

36.3 |

26.29 |

|

|

3 cm or > |

24.63 |

16.2 |

|

|

RT: Radiotherapy; CT: Chemotherapy; TLT: Teletherapy; SD: Standard Deviation |

|||

Table 6: Univariate analysis of overall survival (OS) for different variables in 85 cases of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer.

|

Variable included in the model |

B |

SE |

Wald |

OR (CI 95%) |

P value |

|

Age group |

.042 |

.139 |

.090 |

.794 - 1.37 |

.765 |

|

Previous tretament |

.211 |

.230 |

.840 |

.786 - 1.938 |

.360 |

|

Tumor size |

-.658 |

.266 |

6.095 |

.307 - .873 |

.014* |

Table 7: Multivariate analysis of overall survival (OS) for different variables in 85 cases of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer (Cox Regression).

Only variables that were statistically significant in the univariate were analyzed in multivariate Cox regression models.

Tumor Recurrences: Twenty-three patients (27.0%) developed tumor recurrences within 5-56 months with a median of 11.5 months. In 6 cases (26%), recurrences were local, in 10 (43.4%) locoregional, in 5 (21.7%) locoregional and distant, and in 2 (8.6%) distant only (Table 8). Distant metastases were found in two cases in the supraclavicular lymph nodes and in one case with peritoneal carcinomatosis, para-aortic lymph node metastases, splenic metastases, pulmonary metastases, and bone metastases. Only 2 of these 23 patients (8.7%) achieved disease control with a disease-free follow-up of 36 and 24 months, respectively.

|

Localización |

n |

% |

|

Local |

6 |

26 |

|

Local-regional |

10 |

43.4 |

|

Local-regional and remote* |

5 |

21.8 |

|

Remote* |

2 |

8.7 |

|

Total |

23 |

99.9 |

|

*Two cases in supraclavicular lymph nodes and one case with peritoneal carcinomatosis, paraaortic metastasis, metastasis to the spleen, lung and bone. |

||

Table 8: Tumor recurrences in 23 patients.

Discussion

Radical hysterectomy as salvage surgery in patients who have undergone radiation for cervical cancer (CC) is not recommended due to its high morbidity, and pelvic exenteration (PE) is generally preferred for these cases [1, 3, 8, 9]. This recommendation is reflected in publications on the FIGO staging system for CC in the 2018 and 2021 editions [1, 3], in guidelines for the management of this type of cancer such as those from the European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO) in 2023 [18], and in the chapter on recurrences in CC post-CCRT edited by Disaya JPh et al. in 2018 [8].

In 1987, Rubin CS et al. [10] from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York reported that radical hysterectomy had been an accepted procedure at their institution for post-radiation CC since 1940. However, in contrast to the numerous reports in the literature on the results of pelvic exenteration, they had found only 5 articles related to radical hysterectomy for post-radiation CC, including a series published by the author of this article in 1983 with 50 cases [13]. Rubin CS et al. reported a 47.6% fistula rate and a 9.5% mortality rate in their series of 21 patients. They concluded that due to the morbidity of the procedure, radical hysterectomy should only be performed by highly experienced pelvic surgeons and in patients with recurrences of less than 2 cm [10].

Coleman RL et al., in their 1994 publication with 50 patients who underwent radical hysterectomy for recurrent CC following RT [11], reported a severe morbidity rate of 42% with a 28% fistula rate, a 2% postoperative mortality rate, and a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 72%, suggesting that only patients with lesions less than 4 cm could benefit from this surgery. Maneo A. et al. [12], in a series of 34 patients with persistent and recurrent CC following RT published in 1999, reported a 44% rate of major complications and a 49% disease-free survival rate.

In 1993, Magrina FJ [9] stated in an article on the complications of radical surgery in patients who had previously received RT for gynecologic cancer that this combination is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and therefore radical hysterectomy for recurrent CC following RT should be performed rarely, concluding that this surgery should only be indicated for recurrences of 2 cm or less and performed by an experienced surgeon with excellent technique.

In the series presented here, which spanned 51 years with 85 cases, radical hysterectomy accounted for 8.5% of the 1,024 laparotomies performed for persistent or recurrent CC following RT and CCRT. A previous series of 50 cases published in 1983, covering the years 1966-1979, showed a 36.6% rate of major complications and a 4.7% postoperative mortality rate, compared to 17.1% in 35 cases from 1980-2018 with no postoperative mortality. In 28 of the 85 cases (28.2%), major complications occurred, the most common being fistulas (20/85, 23.5%), of which 14 were urinary tract fistulas and 6 were rectovaginal fistulas.

The surgical technique for radical hysterectomy performed in the Oncology Department of the GHM during the period 1966-1979 included resection of the anterior branches of the hypogastric plexus during parametrium dissection, which contributed to the development of major complications by adding to the poor blood supply of irradiated tissues [9], causing fibrosis that made it difficult to separate the uterus from the bladder and/or rectum, and the ureters from the parametrical and paracervical tissue [9, 16, 17]. This technique is similar to the type 4 classification described by Cibula DU et al. in 2011 [18].

Starting in 1980, our technique preserved the anterior branches of the hypogastric plexus, following the guidelines for class 3 hysterectomy described by Piver M et al. [15]. Major complications in the remaining 35 cases of this series decreased to 17.1%, and postoperative mortality decreased to 0. The rates of major complications for pelvic exenterations (PE) published in this century range from 30% to 70% [19-22]. Therefore, the 17% rate of major complications reported in this communication for 35 RH cases during the period 1980-2018, and the 27% rate in 31 RH cases published in 2017 by Mabuchi S et al. from Osaka University Hospital in Japan [17], represent a reasonable morbidity for this surgery.

This is because the use of stomas, as is common in PE, is avoided, resulting in a quality of life for RH patients that is incomparable to that of exenterated patients. In this series, OS at 34 months was 54.1% for our patients, similar to rates reported in the 1980s and 1990s [9,11,12], and comparable to the 53.8% OS at 34 months reported in 2017 by Mabuchi S et al. [17] in their series of 31 cases. According to Kaplan-Meier curves for DFS and OS in our series, prior treatment with CCRT versus RT (p=0.001 and p=0.013, respectively) and tumor size less than 3 cm (p=0.002 and p=0.038) had a positive impact on prognosis.

In the multivariate analysis, only tumor size less than 3 cm was statistically significant (p=0.014). This finding is consistent with the literature for patients treated with RH as salvage surgery [9,11,12,17,23]. Reyes CA et al. [16] mentioned in 2018 that some recent publications showed better results when surgery was performed after standard treatment for advanced CC, which could be related to surgeons performing hysterectomies shortly after RT to avoid the development of radiation-induced fibrosis. However, performing these surgeries a few weeks after CCRT (4-8 weeks) remains controversial.

In 2010, Walji B et al. [24] from the Cancer Center Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, UK, reported that in a group of patients with advanced CC who did not receive brachytherapy, a higher dose of external beam radiotherapy was administered to one group, while another group underwent adjuvant hysterectomy. They observed a 50% recurrence rate in the radiated patients versus 0% in the operated patients. In 2016, Fanfani F et al. [25] from the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy, compared the outcomes of CCRT versus CCRT plus radical hysterectomy in 150 patients with stage III CC. They reported a significant increase in local recurrences in the CCRT group (77 vs. 73), p=0.0210, a lower number of recurrences in the operated patients, p=0.021, and a 3-year disease-free survival rate of 62.9% versus 68.3%, p=0.0686, favoring the patients who underwent surgery.

Houvenaeghel G et al. [26] from the Department of Surgery, Institute Paoli-Calmettes, Marseilles, France, reported their experience with 35 patients with advanced CC who underwent hysterectomy or pelvic exenteration after receiving CCRT. They reported locoregional control in 88.6% and a 10-year disease-free survival rate of 66.4%, concluding that adjuvant surgery reduces the risk of local recurrences and increases disease-free survival. In a meta-analysis aimed at evaluating the effect of CCRT versus CCRT plus radical hysterectomy, which included 14 studies, Weijia LU et al. [27] reported a higher recurrence rate in patients treated with CCRT alone and better DFS and OS (p=0.007 and p=0.01, respectively) in patients who underwent surgery. They concluded that while the benefit of post-CCRT radical surgery remains controversial, the results indicated that the recurrence rate may be higher in patients treated with CCRT alone.

The 2024 version of the NCCN Guidelines for the management of CC, in the chapter on recurrent CC following CCRT [28], states that radical hysterectomy may be considered as salvage surgery in much selected cases, while the ESGO guidelines for the treatment of CC published in 2023 only refer to PE as a salvage measure for post-RT/CCRT recurrences [29].

Conclusion

The results presented here show for RH a decrease in morbidity from 36% recorded for the years 1966-1979, to 17.1% for the period 1980-2018. With 0% mortality for the last 38 years. These figures are lower than those published at the end of the last century for RH, surgery that avoids the permanent use of stomas used in PE, resulting in an optimal quality of life for these patients.

While PE should always be considered for patients with persistent or recurrent CC to CRRT, radical hysterectomy is a procedure to be considered for cervical tumor of 3 cm or less.

References

- Bhatla N, Berek SJ, Cuello F M, Denny AL, Grenman S, et al. (2018). Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 143: 43-991.

- Islami F, Torre AL, Drope MJ, Ward ME, Jemal A. (2017). Gobal Cancer In Women: Cancer Control Priorities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 26: 458-70.

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Daya N, Sharma ND, Sankaranarayanan R. (2021). Cancer of the cervix uteri: update.Int J GynecolObstet. 155: 28-44.

- Mexico. Source Globocan 2022. Number of new cases both sexes. International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO. P: 1-2.

- Cáncer uterino Datos y Estadísticas (2018). Boletín Epidemiológico. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología México. P: 6-9.

- Torres-L A, Jiménez A EL, Barra-M A, Oliva P JC, Suárez J CA, et al. (2021). Gynecological cancer: Evolution of its relative frequency..Rev Med Hosp GenMex. 84: 41-48.

- Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, et al. (1999). Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 340: 1144-1153.

- Tewari SK, Monk JB. (2018). Invasive Cervical Cancer. In: Clinical Gynecologic Oncology. Eds. Disaia JPh, Mannel SR.Creasman TW et al. Elsevier Philadelphia Ninth Ed. PP: 92.

- Magrina FJ. (1993) Complications of Irradiation and Radical Surgery for Gynecologic Malignancies. Obstetrics and Gynecological Survey; 48: 571-575.

- Rubin CS, Hoskins JW, Lewis LJ. (1987). Radical Histerectomy for Recurrent Cervical Cancer following Radiation Therapy. Gynecologic Oncology. 27: 316-322.

- Coleman RL, Keeney ED, Freedman RS, Burke TW, Eifel PJ, et al. (1994). Radical hysterectomy for recurrent carcinoma of the uterine cervix after radiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 55: 29-35.

- Maneo A, Landonni F et al. (1999). Radical Hysterectomy for Recurrent Ca. Of uterine cervix after radiotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 9: 295301.

- Torres LA, Ceron GM, Mandujano M, Diaz RLR. (1983). Histerectomía radical en el tratamiento del cáncer cervicouterino recurrente a radiación. Ginecología y Obstetricia de México. 51: 7-12.

- Meigs JV. (1944). Carcinoma of the cervix-The Wertheim operation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1944;78: 195–199.

- Piver M, Rutledge F, Smith J. (1974). Five classes of extended hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 44: 265-272.

- Reyes CA, Jiménez AM. (2018). Surgery after Chemoradiation Therapy in Persistent/Recurrent locally Advanced cervical cancer. Is Exenteration Always Necessary?. J Surg. 7: 001-003.

- Mabuchi S, Kozasa K, Kimura T. (2017). Radical hysterectomy after radiotherapy for recurrent or persistent cervical cancer. Obstet and Gynecol. 139: 185-191.

- Cibula D, Abu-Rustum NR, Benedetti-Panici, Köhler P, Raspagliesi C. (2011). New classification system of radical hysterectomy: emphasis on a three-dimensional anatomic template for parametrial resection. Gynecol Oncol. 122: 264-268.

- Lopez J, Barrios L. (2005). Evolution of pelvic exenteration. Surg Oncol Clin of North Am. 14: 587-606.

- Chiva ML, Lapuente F, Gonzalez-Cortijo L, González MA, Rojo A, et al. (2008). Surgical treatment of recurrent cervical cancer: state of the art and new achievements. Gynecol Oncol. 110: S60-6.

- Matsuo K, Mandelbaun S, Adams L, Roman DL, Wright JD. (2019). Performance and outcome of pelvic exenteration for gynecologic malignancies: A population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 153: 368375.

- De Gregorio N, De Gregorio A, Ebner F, Friedl PWT, Huober J, et al. (2019). Pelvic exenteration as ultimate ratio for gynecologic cancers: single-center analyses of 37 cases. Arch Gynecol and Obstet; 300: 161-168.

- Gadducci A, Tana R, Cosio S, Cionini L. (2010). Treatment options in recurrent cervical cancer (Review). Oncology Letters. 1: 3-11.

- Walji B, Chue AL, Yap C, Rogers LJ, El-Modir A, et al. (2010). Is there a Role for Adjuvant Hysterectomy after Suboptimal concurrent Chemoradiation in Cervical Carcinoma?. Clinical Oncology. 22: 140146.

- Fanfani F, Vizza E, Landoni F, de Laco P, Ferrandina G, et al. (2016). Radical hysterectomy after chemoradiation in FIGO stage III Cervical cancer patients versus chemoradiation and braquitherapy: Complications and 3-years survival. Eur J Surg Oncol. 42: 1519-1525.

- Houvenaeghel G, Lelievre L, Gonzague-Casablanca L, Buttarelli M, Moutardier V, et al. (2006). Long-Term survival after concomitant chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery in advanced cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 100: 338-343.

- Weijia LU, Canxiong LU, Z YU, Lei GAO. (2021). Chemoradiotherapy alone vs. chemoradiotherapy and hysterectomy for locally advanced cervical cancer: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Oncology Letters. 21: 160.

- Cervical Cancer. (2024). Cancer NCCN Guidelines. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Version 3: 2024.

- Cibula D, Raspollini RM, Planchamp F, Centeno C, Planchamp C,et al. (2023). ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 33: 649-666.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.