Psychometric Validation of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale in a Sample of Greek Breast Cancer Survivors

by Maria Charalampopoulou1,2*, Vasileios Mantikas3, Georgia E. Laskaridou2, Alexia Georgopoulou2, Panagiotis Daskalakis4, Dimitrios Tryfonopoulos5, Christos Batsis6, Anastasios I. Manettas7,8, Ioanna A. Anastasiou9, Panagiotis Sideris10, Flora Bacopoulou11, Flora Zagouri12, George C. Zografos1, Christina Darviri2

1Breast Unit, First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Hippokratio Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Athens, Greece.

2Postgraduate Course of Stress Management and Health Promotion, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

3Department of Geriatrics, Gesundheitszentrum Dielsdorf, Dielsdorf, Switzerland

4Breast Unit, Elena Venizelou General Hospital, Athens, Greece.

5Second Department of Medical Oncology, Agios Savvas Anticancer Hospital, Greece.

6Second Department of Breast Surgery, Agios Savvas Anticancer Hospital, Greece.

7Department of Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

8Biomechanics and Ergonomics, ErgoMech Laboratory, Department of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Thessaly, Trikala, Greece.

9First Department of Propaedeutic Internal Medicine, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laiko General Hospital, Athens, Greece.

10Internal Medicine Department, 417 Share Fund Hospital, Athens, Greece.

11Center for Adolescent Medicine and UNESCO Chair on Adolescent Health Care, First Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Aghia Sophia Children’s Hospital, Athens, Greece.

12Department of Clinical Therapeutics, Alexandra Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens School of Medicine, Athens, Greece.

*Corresponding author: Maria Charalampopoulou, Breast Unit, First Department of Propaedeutic Surgery, Hippokratio Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Athens, Greece.

Received Date: 14 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 23 December, 2025

Published Date: 26 December, 2025

Citation: Charalampopoulou M, Mantikas V, Laskaridou GE, Georgopoulou A, Daskalakis P, et al. (2025) Psychometric Validation of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale in a Sample of Greek Breast Cancer Survivors. J Oncol Res Ther 10:10319. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574710X.10319

Abstract

Background: Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is one of the most prevalent concerns among breast cancer survivors, affecting psychological well-being, quality of life, and engagement in follow-up care. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS) is widely used internationally to assess FCR, but no validated version exists for Greek-speaking survivors. This study aimed to translate and validate the Greek version of the CARS. Methods: A sample of 219 Greek breast cancer survivors completed the translated CARS along with measures of anxiety and depression. Psychometric analyses included confirmatory factor analysis to test the original fourfactor structure, evaluation of internal consistency, and assessment of convergent validity. Results: The Greek version of the CARS replicated the four-factor model of the original instrument. Standardized factor loadings were satisfactory, and model fit indices indicated good structural validity. Internal consistency was excellent across subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.85 to 0.93). Convergent validity was supported through significant associations with anxiety and depression measures. Conclusions: The Greek CARS demonstrates strong psychometric properties and provides a reliable tool for assessing FCR in Greek breast cancer survivors. Its use in clinical practice may facilitate systematic screening and guide the development of supportive care interventions. Furthermore, the availability of a Greek version contributes to international efforts to enable cross-cultural comparisons in survivorship research.

Keywords: Breast Neoplasms / Psychology; Fear of Cancer Recurrence; Psychometrics; Survivors / Psychology; Survivorship Care; Psycho-Oncology.

Introduction

Cancer survivorship often brings long-term psychological and emotional challenges, with one of the most persistent being the distress related to the possibility of cancer returning. For many survivors, particularly those with a history of breast cancer, concerns about recurrence can continue well after treatment completion and may influence psychological well-being, quality of life, and engagement with follow-up care [1, 2]. Although some level of worry is expected, sustained and intense concern has been associated with clinically significant symptoms of anxiety, depression, and impaired.

These worries are not limited to fear of death or physical decline. Survivors may experience distress related to body image, femininity, social roles, and personal identity, which are often deeply intertwined with cultural and societal expectations [3, 4]. This highlights the importance of using tools that assess both the emotional intensity and the multidimensional nature of recurrencerelated distress.

The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS), developed by [5], offers a structured and validated way to capture such experiences. It includes both a general index of worry and subscales addressing specific domains: Health Worries, Womanhood Worries, Role Worries, and Death Worries. While the CARS has been successfully adapted into Dutch [6], Japanese [7] and Spanish-speaking population [8], a Greek version has been lacking. Cultural factors, including communication styles, coping behaviors and attitudes toward illness, underscore the necessity of validating this tool within Greek-speaking populations.

The current study aimed to fill this gap by translating and culturally adapting the CARS for use among Greek breast cancer survivors. In addition to examining the internal consistency and factorial validity of the adapted scale, the study assessed its convergent validity with psychological distress indicators, specifically anxiety, depression, and perceived stress.

Methods

Participants

A total of 219 breast cancer survivors were recruited through convenience sampling from four oncology clinics located in Athens, Greece (Hippocration, Alexandra, Agios Savvas, and Elena Venizelou). Eligibility criteria included being 18 years or older, having completed primary cancer treatment (excluding ongoing hormonal therapy), and demonstrating sufficient fluency in Greek to complete self-report questionnaires. Patients with significant cognitive impairment or active psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Protocol no.2021032325). Data were collected between October 2024 and May 2025. After providing informed consent, participants completed a paper-based survey comprising demographic and clinical questions, the Greek-translated version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS14).

Translation and Cultural Adaptation

Translation of the CARS followed established cross-cultural adaptation guidelines. Two independent bilingual translators first translated the original English version into Greek. Discrepancies were reconciled through consensus, followed by a back-translation conducted by a native English speaker unfamiliar with the original scale. The back-translated version was reviewed for conceptual equivalence. To ensure clarity and cultural relevance, a pilot group of ten breast cancer survivors participated in cognitive debriefing interviews.

Measures

Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS)

The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS) consists of 30 items [5]. The first four items assess the frequency, intensity, consistency, and functional impact of recurrence-related thoughts using a 6-point Likert scale. These items form a general index of recurrence concern severity. The remaining 26 items assess four domains—Health Worries, Womanhood Worries, Role Worries, and Death Worries—rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) includes 14 items split into two subscales measuring anxiety and depression. Responses are scored on a 4-point scale (0–3), with subscale totals ranging from 0 to 21. The following cut-off points are commonly used to interpret symptom severity: 0–5 (normal), 6–8 (mild), 9–11 (moderate), and 12–21 (severe) [9]. The Greek version has demonstrated good psychometric properties in oncology populations [10].

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) measures perceived stress over the past month using 14 items rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Although not formally validated in Greek oncology settings, it has shown good internal consistency in Greek samples [11].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic, clinical, and psychometric data. Internal consistency for each scale and subscale was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and interpreted alongside item-level and structural evidence. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the fit of the original four-factor model using Jamovi version 2.6 [12]. Item-level functioning was examined through standardized CFA factor loadings and their statistical significance. Convergent validity was assessed using Pearson correlations between CARS subscales and HADS and PSS-14 scores. Group comparisons based on HADSdefined psychological distress levels were performed using oneway analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests. Known-groups validity was examined by comparing CARS scores across subgroups defined by time since diagnosis, cancer stage, employment status, and income satisfaction. Due to the crosssectional design, temporal stability (test–retest reliability) could not be assessed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study included 219 breast cancer survivors, with a mean age of 52.60 years (SD ± 8.12; range: 39–73). Most participants lived in Athens (79.0%), were currently employed (76.3%), with a higher education degree (48.9%). The majority was married (56.6%) with children (76.7%). Clinically, 86.8% had early-stage breast cancer (Stage 0–II), and 57.5% were diagnosed within the past two years. The most common surgical treatment was lumpectomy (61.2%), followed by mastectomy (38.8%), with only 18.7% undergoing breast reconstruction. A total of 81.7% received radiation therapy, 58.9% received chemotherapy, and 74.9% were under hormonal treatment. Among those on hormonal therapy, 58.9% used aromatase inhibitors, and 39.2% were on SERMs. Regarding menopausal status, 65.3% were postmenopausal. A family history of breast cancer was reported by 30.1%, and 75.7% had at least one comorbid condition. Current smoking was reported by 33.3% and alcohol consumption by 48.4%. In more details see Table 1.

|

Variable |

N (%) |

Variable |

N (%) |

|

Age in years |

Years since diagnosis |

||

|

Mean ± SD |

52.60 ± 8.12 |

<2 years |

76 (34.7) |

|

Min-max |

39 -73 |

2-5 years |

126 (57.5) |

|

Place of Residence |

> 5 years |

17 (7.8) |

|

|

Athens |

173 (79.0) |

Cancer stage (AJCC) |

|

|

Outside of Athens |

46(20.9) |

Early (Stage 0-II) |

190 (86.8) |

|

Family status |

Advanced (III+) |

15 (6.8) |

|

|

Single |

34 (15.5) |

Unknown |

14 (6.4) |

|

Married |

124 (56.6) |

Surgery type |

|

|

Divorced |

50(22.8) |

Lumpectomy |

134 (61.2) |

|

Widowed |

11(5.0) |

Mastectomy (± expanders) |

85 (38.8) |

|

Parity |

Breast reconstruction |

||

|

yes |

168 (76.7) |

Yes |

41 (18.7) |

|

no |

49 (22.4) |

No |

178 (81.3) |

|

Educational level |

Adjuvant Therapies |

||

|

Low |

22(10.0) |

Radiation |

179 (81.7) |

|

Medium |

90(41.1) |

Chemotherapy |

129 (58.9) |

|

High |

107(48.9) |

Hormonal |

164 (74.9) |

|

Currently employed |

Hormonal Therapy Drugs |

||

|

yes |

167 (76.3) |

Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs) |

96 (58.9) |

|

no |

52 (23.7) |

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) |

64 (39.2) |

|

Income satisfaction |

Other / Unknown |

3 (1.8) |

|

|

Not satisfied |

67 (30.6) |

≥1 Comorbid Condition |

|

|

Somewhat satisfied |

114 (52.1) |

yes |

165 (75.7) |

|

Very satisfied |

38 (17.4) |

no |

54 (24.3) |

|

Menopausal status |

Smoking status |

||

|

Premenopausal |

143 (65.3) |

Current |

73 (33.3) |

|

Postmenopausal |

74 (33.8) |

Former |

30 (13.7) |

|

Unknown |

2 (0.9) |

Never |

116 (53.07) |

|

Family history of breast cancer |

Alcohol consumption |

||

|

Yes |

66 (30.1) |

yes |

106 (48.4) |

|

No |

153 (69.9) |

no |

113 (51.6) |

|

Values are presented as number of participants (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. Comorbid conditions include cardiovascular, endocrine and other chronic illnesses. |

|||

Table 1: Sociodemographic and Medical Characteristics of the Participants (N=219).

Descriptive Statistics and Internal Consistency

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and reliability estimates for all measures. The CARS Total score (items 5–30) had a mean of 50.96 (SD ± 26.97) and demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.97). Subscale internal consistency ranged from α = 0.85 (Death Worries) to α = 0.93 (Health Worries), with mean scores of 19.40 for Health Worries, 9.36 for Womanhood Worries, 11.15 for Role Worries, and 11.09 for Death Worries. The Overall Worries subscale (items 1–4) showed a mean of 11.54 (SD ± 5.28) and α = 0.93.

For the validation measures, HADS-Anxiety (Mean = 5.51, SD ± 3.98, α = 0.85), HADS-Depression (Mean = 16.12, SD ± 3.79, α = 0.81), and PSS-14 (Mean = 21.53, SD ± 9.31, α = 0.88) all demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. Item-level CFA results further supported adequate item functioning, with all items exhibiting statistically significant standardized loadings on their respective latent factors. Accordingly, high internal consistency estimates were interpreted in conjunction with the multidimensional factor structure and item-level evidence, rather than as standalone indicators of scale quality.

|

Measure |

No. of items |

Mean Range |

Mean ± SD |

Cronbach’s α |

|

CARS-Overall Worries |

4 |

1-6 |

11.54 ± 5.28 |

0.93 |

|

CARS-Health Worries |

8 |

0-4 |

19.40 ± 8.78 |

0.93 |

|

CARS-Womanhood Worries |

6 |

0-4 |

9.36 ± 7.10 |

0.91 |

|

CARS-Role Concerns |

6 |

0-4 |

11.15 ± 6.74 |

0.89 |

|

CARS-Death Concerns |

6 |

0-4 |

11.09 ± 6.49 |

0.85 |

|

CARS-Total (items 5-30) |

26 |

0-4 |

50.96 ±26.97 |

0.97 |

|

PSS-14 |

14 |

0-4 |

21.53 ± 9.31 |

0.88 |

|

HADS-Anxiety |

7 |

0-3 |

5.51 ± 3.98 |

0.85 |

|

HADS-Depression |

7 |

0-3 |

16.12 ± 3.79 |

0.81 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency reliability. CARS-Overall Worries subscale includes items 1–4 with responses from 1 (not at all) to 6 (all the time); subscale scores range from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). All subscale means reflect averaged scores unless otherwise specified. |

||||

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Psychometric Measures.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

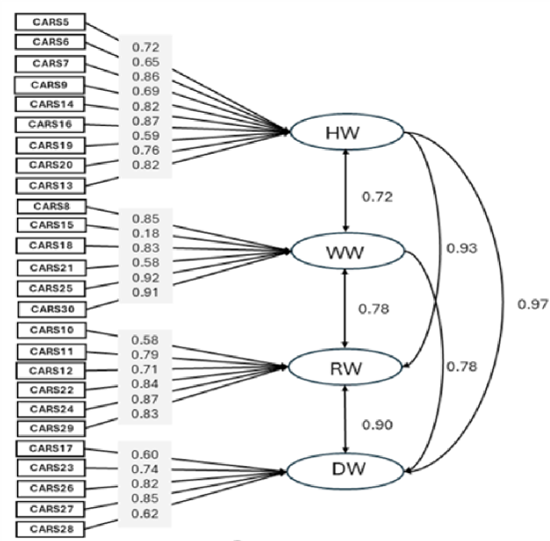

Standardized factor loadings from the CFA supported the four-factor model, with all items loading significantly on their respective factors (range: 0.58–0.92; p < 0.001). Model fit indices indicated a moderate fit: χ² (269) = 1193.3, CFI = 0.810, TLI = 0.788, RMSEA = 0.125, SRMR = 0.087. Inter-factor correlations were high and significant (p < 0.001), with the strongest between Health and Death Worries (r = 0.97), followed by Role and Death Worries (r = 0.90). The confirmatory factor analysis model with standardized factor loadings and inter-factor correlations is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Greek version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS-GR).

Latent variables are represented as ellipses: HW = Health Worries; WW = Womanhood Worries; RW = Role Worries; DW = Death Worries. Observed variables (CARS items) are shown in rectangles. Standardized factor loadings are displayed next to the singleheaded arrows, and standardized correlations between latent factors are displayed next to the double-headed arrows. All loadings and correlations were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Convergent Validity

CARS Total scores showed moderate to strong correlations with psychological distress measures (all p < 0.001). The CARS Total correlated positively with HADS-Anxiety (r = 0.548) and PSS-14 (r = 0.347), and HADS-Depression (r = 0.440). Subscale correlations with HADS-A ranged from r = 0.304 (Overall Fear) to r = 0.533 (Womanhood Worries). Similar patterns were observed for PSS-14 and HADS-D. Details are presented in Table 3.

|

CARS Measure |

HADS-A |

HADS-D |

PSS-14 |

|

Pearson’s r |

|||

|

CARS Total |

0.548 |

0.440 |

0.347 |

|

Overall Fear |

0.304 |

0.346 |

0.304 |

|

Health Worries |

0.501 |

0.343 |

0.308 |

|

Womanhood worries |

0.533 |

0.401 |

0.356 |

|

Role Worries |

0.521 |

0.419 |

0.347 |

|

Death Worries |

0.477 |

0.326 |

0.279 |

|

All are statistically significant at p <0 .001. |

|||

Table 3: Convergent Validity for CARS.

Correlations with Participant Characteristics

As shown in Table 4, younger age (r = -0.175**), shorter time since diagnosis (r = -0.185**), lower income satisfaction (r = -0.207**), and advanced cancer stage (r = -0.203**) were significantly associated with higher CARS scores. Radiation therapy (r = -0.167*), unemployment, and comorbidities (r = 0.173*) were also significant factors. Family status, residence, and surgical type showed smaller but significant associations. Menopausal status and educational level showed no consistent patterns.

|

Variable |

CARS Total |

Overall worries |

Health worries |

Womanhood Worries |

Role Worries |

Death Worries |

|

Age |

-0.175** |

-1.168* |

-0.155* |

-0.162* |

||

|

Residence |

-0.140* |

-0.151* |

-0.199** |

|||

|

Family status |

0.193** |

0.155* |

0.211** |

0.161* |

0.168* |

|

|

Educational level groups |

0.144* |

|||||

|

Currently employed |

-0.153* |

-0.156* |

-0.147* |

-0.169* |

-0.143* |

|

|

Income satisfaction |

-0.207** |

-0.174* |

-0.207** |

-0.197** |

-0.176** |

-0.182** |

|

Cancer stage (AJCC) |

-0.203** |

-0.148* |

-0.147* |

|||

|

Years since diagnosis |

-0.185** |

-0.266** |

-.186** |

-0.155* |

-0.214** |

|

|

Menopausal status |

-0.139* |

|||||

|

Surgery type |

-0.177** |

-0.143* |

||||

|

Hormonal Therapy Drugs |

0.155* |

|||||

|

Radiation therapy |

-0.167* |

-0.149* |

-0.159* |

-0.143* |

-0.157* |

-0.206** |

|

Comorbidities |

0.173* |

0.173* |

0.147* |

0.213** |

||

|

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. |

||||||

Table 4: Correlations between CARS total score and subscales with characteristics of the study’s sample.

Known-Groups Validity

As shown in Table 5, CARS total scores significantly differed across both HADS-Anxiety and HADS-Depression subgroups.

For anxiety, participants in the Normal HADS-A group reported significantly lower CARS scores (Mean = 39.13, SD ± 24.93; a) compared to those in the Mild (Mean = 64.44, SD ± 21.06; b) and Moderate (Mean = 59.08, SD ± 21.26; b) groups. The Severe group had the highest scores (Mean = 75.78, SD ± 17.13; c), significantly different from all other groups.

For depression, individuals in the Mild (Mean = 79.22, SD ± 2.69; a) and Moderate (Mean = 64.90, SD ± 19.52; a) groups reported significantly higher CARS scores than those in the Severe group (Mean = 47.88, SD ± 26.77; b).

|

Group |

N |

Mean CARS-Total |

|

HADS-Anxiety |

||

|

Normal |

123 |

39.13 ± 24.93 a |

|

Mild |

48 |

64.44 ± 21.06 b |

|

Moderate |

25 |

59.08 ± 21.26 b |

|

Severe |

23 |

75.78 ± 17.13 c |

|

HADS-Depression |

||

|

Mild |

9 |

79.22 ± 2.69 a |

|

Moderate |

21 |

64.90 ± 19.52a |

|

Severe |

189 |

47.88 ± 26.77b |

|

Note: Means sharing the same letter within each subscale do not differ significantly (Tukey HSD, p < 0.05). |

||

Table 5: CARS Total scores by HADS-A and HADS-D Groups.

These results confirm the known-groups validity of the CARS-GR, showing its ability to distinguish between survivors with varying levels of psychological distress.

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive validation of the Greek version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS-GR) in a large sample of breast cancer survivors. The findings indicate that the CARS-GR is a reliable and valid instrument for assessing fears related to cancer recurrence in Greek-speaking populations, consistent with prior international validations [5,6,7,8]. Internal consistency estimates for the overall scale and subscales were high and comparable to those reported in the original and adapted versions of the instrument.

Confirmatory factor analysis supported the hypothesized fourfactor structure of the CARS, although model fit indices were moderate. Such findings are not uncommon in cross-cultural psychometric research, where cultural interpretations of illness, identity, and survivorship may influence response patterns [13]. Importantly, all items loaded significantly and meaningfully on their respective latent factors, supporting the theoretical integrity and construct representation of the scale. Although internal consistency estimates were high, this pattern is consistent with the nature of fear of cancer recurrence, which comprises closely interrelated cognitive and emotional concerns. High alpha values may therefore reflect conceptual coherence of item content rather than problematic redundancy. In addition, the strong correlations observed between certain domains, particularly Health and Death Worries; likely represent genuine conceptual overlap in survivorship contexts, where somatic threat and existential concerns frequently co-occur.

The observed associations between recurrence-related concerns and psychological distress, particularly anxiety and perceived stress, are in line with previous research [1, 2, 14]. Notably, the Womanhood and Role Worries subscales demonstrated stronger associations with anxiety than the Health or Death Worries subscales. This finding highlights that fear of recurrence extends beyond health-related or existential concerns to encompass issues related to femininity, body image, and social roles, especially among younger survivors [15]. These dimensions are particularly relevant within psycho-oncological frameworks that emphasize the importance of individualized, gender-sensitive psychosocial interventions in survivorship care [16].

Sociodemographic and clinical correlates of fear of cancer recurrence identified in this study, including younger age, shorter time since diagnosis, and lower income satisfaction, are consistent with developmental models that underscore the role of life stage and socioeconomic burden in shaping vulnerability to recurrence-related fears [17, 18]. In contrast, broader clinical variables such as disease stage or treatment exposures showed less consistent associations, suggesting that fear of recurrence may transcend traditional clinical boundaries or vary across populations. Educational attainment and menopausal status were not consistently associated with recurrence concerns, reflecting the mixed findings reported in the literature [19, 20].

Known-groups validity was further supported by the scale’s ability to differentiate survivors according to levels of psychological distress. Participants with severe anxiety reported significantly higher CARS total scores than those with moderate, mild, or no anxiety. In the depression analyses, survivors with mild depressive symptoms reported the highest levels of recurrence concerns, followed by those with moderate and severe symptoms. This counterintuitive pattern, also reported in previous studies [14], may reflect heightened cognitive engagement and awareness among individuals with moderate distress, leading to increased reporting of fears. Collectively, these findings support the utility of the CARS-GR as a sensitive measure capable of identifying survivors across a broad spectrum of psychological symptomatology.

Clinical Implications

The CARS-GR emerges as a practical, culturally attuned tool for systematically identifying breast cancer survivors experiencing elevated FCR. By capturing multiple domains of concern, it allows clinicians to tailor psychosocial support to survivors’ specific needs, beyond what general measures of anxiety or depression can detect. Routine implementation in survivorship care pathways may enable earlier identification of at-risk survivors, particularly younger, recently diagnosed, or socioeconomically vulnerable women, and support timely referral to interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based programs, or structured survivorship support groups [16, 1]. The Greek CARS also facilitates international comparisons, contributing to global psycho-oncology efforts to harmonize FCR measurement [5,6,7,8].

Strengths and Limitations

This study followed internationally accepted guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation [13] and applied a comprehensive psychometric evaluation, including confirmatory factor analysis, convergent validity, and known-groups validity. The relatively large sample, recruited from multiple oncology clinics, enhances the generalizability of the findings within the Greek healthcare system.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes assessment of temporal stability, including test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change over time. In addition, although the Perceived Stress Scale performed well in the present study, it has not yet been formally validated in Greek oncology populations, which may limit interpretation of stress-related findings. Finally, while the hypothesized factor structure was supported, the moderate fit indices observed suggest that further refinement may be warranted in future studies. Measurement invariance across demographic or clinical subgroups was not examined and should be evaluated in larger samples specifically designed for multi-group analyses.

Conclusion

The Greek version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS-GR) demonstrates robust psychometric properties and cultural adaptability for assessing fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Its strong internal structure, reliability, and validity support its use as a clinical screening tool and a research instrument in psycho-oncology and survivorship care. Incorporating the CARS-GR into routine follow-up could enhance early detection of psychological distress and inform development of tailored, culturally sensitive interventions. Future research should examine its test–retest reliability, longitudinal responsiveness, and applicability across other cancer survivor groups, ensuring that concerns about recurrence are systematically addressed as part of comprehensive survivorship care.

References

- Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Mutsaers B, Thewes B, et al. (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Supportive Care in Cancer 24: 3265-3268.

- Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, et al. (2013) Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 7: 300322.

- Luigjes-Huizer YL, Tauber NM, Humphris G, Kasparian NA, Lam WW, et al. (2022) What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psycho‐Oncology 31: 879-892.

- Tauber NM, O’Toole MS, Dinkel A, Galica J, Humphris G, et al. (2019) Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 37: 2899-2915.

- Vickberg SMJ (2003) The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 25: 16-24.

- van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Peters ML, de Rijke JM, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, et al. (2008) Concerns of former breast cancer patients about disease recurrence: a validation and prevalence study. Psycho‐Oncology 17:1137-1145.

- Momino K, Akechi T, Yamashita T, Fujita T, Hayahi H, et al. (2014) ‘Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS-J). Jpn J Clin Oncol 44: 456-62.

- Ramírez-Orozco M, Rojas-Russell ME, Galindo-Vázquez O, RoblesGarcía R, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. (2023) ‘Concerns about cancer recurrence in Mexican women breast cancer survivors. Psychometric properties of the CARS scale. Ciencias Psicológicas 17.

- Zigmond AS and Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 67: 361-370.

- Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Galanos A, et al. (2004) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Greek cancer patients: psychometric analyses and applicability. Supportive Care in Cancer 12: 821-825.

- Charalampopoulou M, Syrigos K, Filopoulos E, Megalooikonomou V, Vlachakis D, et al. (2020) Reliability and validity of the newly diagnosed Breast Cancer Stress scale in the Greek population. J Mol Biochem 9: 5-12.

- The jamovi project (2025) Jamovi (Version 2.6).

- Hambleton RK, Merenda PF, Spielberger CD (eds) (2004) Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V (2013) Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥5 years) cancer survivors-a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho‐Oncology 22: 1-11.

- Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, et al. (2012) Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Supportive care in cancer 20: 2651-2659.

- Fardell JE, Thewes B, Turner J, Gilchrist J, Sharpe L, et al. (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 10: 663-673.

- Mehnert A, Koch U, Sundermann C, Dinkel A (2013). Predictors of fear of recurrence in patients one year after cancer rehabilitation: a prospective study. Acta Oncologica 52: 1102-1109.

- Crist JV and Grunfeld EA (2013) Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psycho‐Oncology 22: 978-986.

- Dunn LB, Langford DJ, Paul SM, Berman MB, Shumay DM, et al. (2015). Trajectories of fear of recurrence in women with breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 23: 2033-2043.

- Reed SC, Berrett-Abebe J, Whitney RL, Sarkar S, Bell JF (2021) Relationships between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety and worry, and health behaviors and health service use: A systematic review. Journal of psychosocial oncology research and practice 3: e064.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.