Prolonged Behavioral Health Holds in the Pediatric Emergency Department: Patterns and Systemic Strain

by Fatima Sukhera1*, Ayesha Sajid2, Jaclyn Urquiola Sorzano1, Justin Dvorak3, Michael Anderson3, Curtis Knoles1

1Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, USA

2College of Medicine, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, USA

3Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, USA

*Corresponding author: Fatima Sukhera, Department of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 940 NE 13th Street, Suite 2G-2300, Oklahoma City, OK 73104, USA

Received Date: 20 December, 2025

Accepted Date: 29 December, 2025

Published Date: 31 December, 2025

Citation: Sukhera F, Sajid A, Sorzano JU, Dvorak J, Anderson M, et al. (2025) Prolonged Behavioral Health Holds in the Pediatric Emergency Department: Patterns and Systemic Strain. J Hosp Health Care Admin 9: 180. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-6472.000080

Abstract

Objective: There has been a significant increase in the number of patients presenting to the Pediatric Emergency Departments for behavioral health complaints. This paper reviews the demographics, diagnoses, psychiatric histories and reported adverse childhood experiences of these patients, in addition to analyzing the hospital revenue lost resulting from the lack of reimbursement. Method: This is a retrospective study, done by extracting data from the hospital’s data warehouse. We reviewed the charts for patients seen in the Pediatric Emergency Department of a medium sized tertiary, urban, academic hospital from January 2nd, 2020 – September 22nd, 2022 for behavioral health complaints. Results: A steady increase in behavioral health patient visits from 2020 to 2022 was noted and 14.5% of the total number of patients had at least two or more ED visits during the study period. The average age for patients presenting to the ED with behavioral health complaints was 13.86 years, 70.2% patients were biologically female and the most common race reported was white. 97.3% of patients reported suicidal ideation and only 8.2% reported homicidal ideation. Review of our data showed that behavioral health patients stayed in the ED for an average of 2,038 minutes compared to 261 minutes for patients presenting with similar triage level for medical complaints. The hospital received an average of $8/hour reimbursement from insurance companies which was 6.8% of what was billed. Conclusion: This study highlights the increasing prevalence of behavioral health issues in our pediatric and adolescent populations and sheds light on critical gaps in both outpatient and inpatient mental health resources for children and adolescents. More resources are required at both local and national levels to help pediatric patients deal with stressors from adverse childhood experiences.

Keywords: Pediatric behavioral health; Pediatric emergency department; Prolonged holds; Adverse childhood experiences; Suicidal ideation; Depression

Introduction

Pediatric Emergency Departments treat patients presenting with a wide variety of illnesses, ranging from minor cuts and scrapes to level one traumas with neurological deficits and traumatic amputations. With the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the number of patients checking in to the Pediatric Emergency Departments has drastically changed. Most recently, there has been a greater influx of patients checking in for behavioral and psychiatric complaints likely due to lack of available outpatient resources. This has been a trend nationwide with a well-documented increase in the number of patients presenting specifically for suicidal ideation [1].

According to one study during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, up to one third of high school students reported poor mental health [2], with reports of up to a fivefold increase in suicidality in the past decade [3].

Background

The Surgeon General of the United States issued an advisory in 2021 regarding the devastating effects the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had on pediatric mental health [4]. Despite several recommendations made and attempts to implement outpatient resources, there has not been a downtrend in the number of patients presenting with behavioural health and psychiatric concerns.

A small portion of patients checking in are stable for discharge home while the majority are held in the ED until an inpatient psychiatric facility can accept them. Unfortunately, ED’s are not well equipped to treat patients with acute psychiatric illnesses [5]. Some ED’s have implemented tele-psychiatry [6], however this service is still not available at all hours. Other barriers include loud environments that are not nurturing for patients and can lead to further aggravation and escalation of already difficult situations. Patients are held for hours on end, in windowless rooms, without structured schedules which; further worsens disorientation and delirium and can lead to frustrated patients and caregivers.

Boarding patients while awaiting inpatient psychiatric evaluation, placement and safe disposition planning leads to utilization of several different types of resources. This also leads to a heavy financial burden on the hospital system along with delays in definitive treatment. Patients being held for behavioral health reasons require labs (as required by admitting psychiatric hospitals), restraints, sitters, medications, and consultations with psychiatrists, social workers and case management, which are all at an added cost. The length of stay (LOS) of patients presenting for psychiatric and behavioral health complaints is also significantly longer compared to thos with medical complaints. One study in an adult ER’s showed a 42% increased LOS for mental health patients [7], another study similarly found that older age, absence of insurance and the need for detoxification significantly prolonged LOS [8]. A study done during 2020 reviewed boarding of pediatric behavioral health patients in the ED and reported an average length of stay of 5 to 41 hours [9], while another study done noted increase in LOS post SARS-CoV-2 [10].

A study reviewing the financial impact of boarding psychiatric patients in an adult ED showed a direct loss of $1,198 per patient, compared to non-psychiatric admissions. Considering the loss of revenue from not being able to see additional patients in rooms that are occupied by behavioral health patients, it is estimated that patient boarding (for psychiatric reasons) cost the department $2,264 per patient [11].

We reviewed the census and data from a medium-sized tertiary, urban, and academic hospital. At the time of our data collection, our Pediatric ED had 25 beds with 2 family waiting rooms often used for patient evaluation/care and frequent use of three to four hall beds depending on the daily census. Of these 25 beds, 3 beds are specialty, ambient experience behavioral health rooms that allow patients a calmer environment. Following the national trend, our ED has also noted a boarding crisis and larger daily census of patients boarding for psychiatric and behavioral health complaints. While there is much literature and data supporting these changes in adult ED’s, not many tertiary pediatric ED’s have published information regarding the boarding crisis secondary to behavioral health holds and associated loss of revenue.

Research Design and Methods

A retrospective study, approved by the Institutional Review board, was done by extracting data from the hospital’s data warehouse. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10) was utilized for an accurate study population selection.

Our data retrieval included patients seen in the Pediatric Emergency Department at a medium sized tertiary, urban, academic hospital from January 2nd, 2020 – September 22nd, 2022 for behavioral health complaints. We manually reviewed medical records for the included patient population to ensure accurate data retrieval. For a more thorough and accurate analysis, we reviewed the

History of Present Illness (HPI) and Medical Decision Making (MDM), which were all documented in the ED progress notes in our Electronic Medical Records to confirm accurate diagnosis, presenting complaints, previous history of behavioral health problems, family history and adverse childhood experiences that may have contributed to patient’s current condition. In addition, demographics including gender, race, age, sexual identity and type of insurance were reviewed.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: All patients checking in to the Emergency Department from January 2nd, 2020 – September 22nd, 2022 with a diagnosis related to behavioral health such as depression, anxiety, aggression, suicidal ideation and homicidal ideation.

Exclusion criteria: Patients seen in the Emergency Department for complaints not related to mental/behavioral health issues and patients who presented to triage but left prior to physician evaluation.

Statistical Methods

Data was obtained from our Electronic Medical Records for patients, ages 0 to 21 years, who presented to the Emergency Department between January 2nd, 2020 – September 22nd, 2022 for behavioral health complaints. Data extraction included patient identifiers, demographics, visit information, medication, lab work, imaging, electrocardiogram and diagnoses, as well as relevant histories and clinical documentation. The desired variables already reside in the University’s Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) environment managed by the Biomedical and Behavioral Methodology Core (BBMC; https://ouhsc.edu/ bbmc/). Patient identifiers were used by the study investigators to abstract additional information from the patient chart, to include:

- Clarification of data points if not made clear by information obtained by data extraction.

- Review of MDM and HPI to identify possible gender identity issues and other associated or confounding factors.

Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic and clinical variables. Categorical variables were tabulated as frequency (%), and continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and tabulated as mean (sd) or median (25th%, 75th%), as appropriate. The number of patients held for behavioral health issues and their boarding duration were tabulated for each year of the study and plotted over time. Visual inspection of these plots as well as linear regression techniques were used to determine whether there has been an increasing trend in the number of boarders and/or their duration of boarding over that period. Cost data were obtained and used to estimate the actual costs of boarders of behavioral health issues as well as the opportunity costs (bed turnover decreased due to high or extended occupancy of behavioral health issue boarding). 95% confidence intervals on these estimates are provided.

Duration of stay was computed for each patient as the average difference between visit stop date and visit start date. The presence of labs was computed within patients as “Yes” if a patient received labs on at least one visit in the study period, and “No” otherwise. Restraint orders were computed for each patient as “Yes” if the patient had at least one order during the study period, and “No” otherwise. The number of restraint orders was summarized as median per patient. Age at admission was computed as the interval in years between the patient’s date of birth and the visit start date for the patient’s first recorded admission during the study period.

For dichotomous flags pulled from EMR data (1/0), blank cells were treated as “0.” Then, binary values were converted to “Yes” / “No” for computing summary statistics.

For ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience) strings, all entered strings were converted to upper case and then matched to exact criteria strings or related strings in the exported data. For example, “Estranged parent” would also include “Estranged parents”. Where observed, typographical errors in the exported data were corrected.

All ICD-10 descriptions, including disorder categories, poisonings, and toxic effects, were computed within patient as “Yes” if the patient had that ICD-10 code or associated text descriptor on at least one visit during the study period, and “No” otherwise.

The raw data used for this analysis contained 243,710 records, representing 2,301 visits and 2,028 unique patients. After restricting visits to within the study period, and to patients who had at least one visit in the categories of interest, the dataset consisted of 814 visits and 723 unique patients. A thorough chart review was done after which six patients were noted to be included in error, resulting in a total of 717 unique patients.

Results

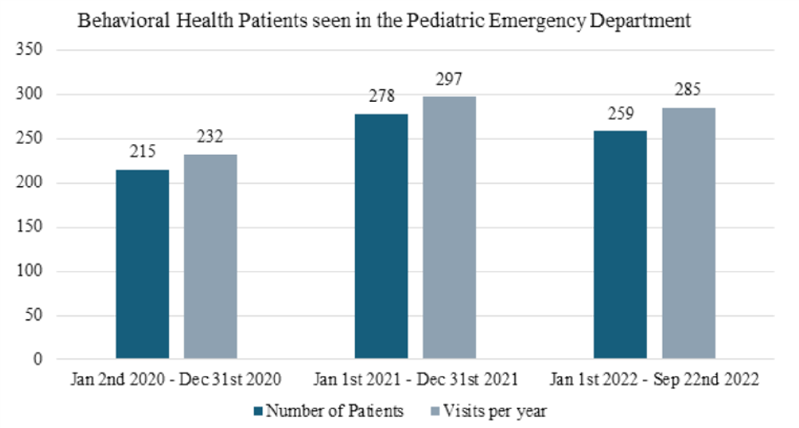

A steady increase in behavioral health patient visits from 2020 to 2022 was noted, from 232 visits in 2020 to 297 in 2021, with an anticipated 350 visits by the end of 2022. Due to complications with obtaining complete and accurate data from our data warehouse, we only received information for 9.8 months of 2022 for which we had 285 visits (Figure 1.0).

Figure 1: Census of Pediatric Patients presenting to Pediatric ED for Behavioral Health complaints.

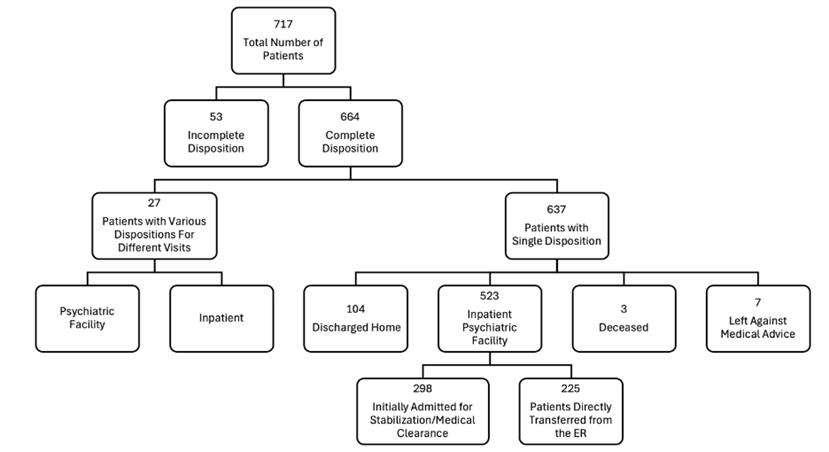

We found that 104/717 (14.5%) of patients had at least two or more ED visits during the study period, with one patient having 17 visits within the study period. Of those 104 patients with at least two or more ED visits, 27 of them were safe to discharge home during some visits and transferred to an inpatient psychiatric facility during a different ED encounter.

There was a large percentage of patients requiring admission to the hospital; 54% (387/717) patients had at least one admission either to our inpatient hospital floor or pediatric intensive care unit for medical management versus observation. Three of these patients unfortunately passed away in the intensive care unit during their hospitalization.

Due to challenges with our electronic medical records, we were unable to determine the disposition of 53/717 patients. Of the 664 patients with an accurate disposition available for review, seven patients left against medical advice from the ED prior to appropriate evaluation and consultations. 15.7% (104/661) were discharged home and 79.1% (523/661) were transferred to an inpatient psychiatric facility, of which 225 were transferred directly from the ED without being admitted to the hospital (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Disposition of Patients.

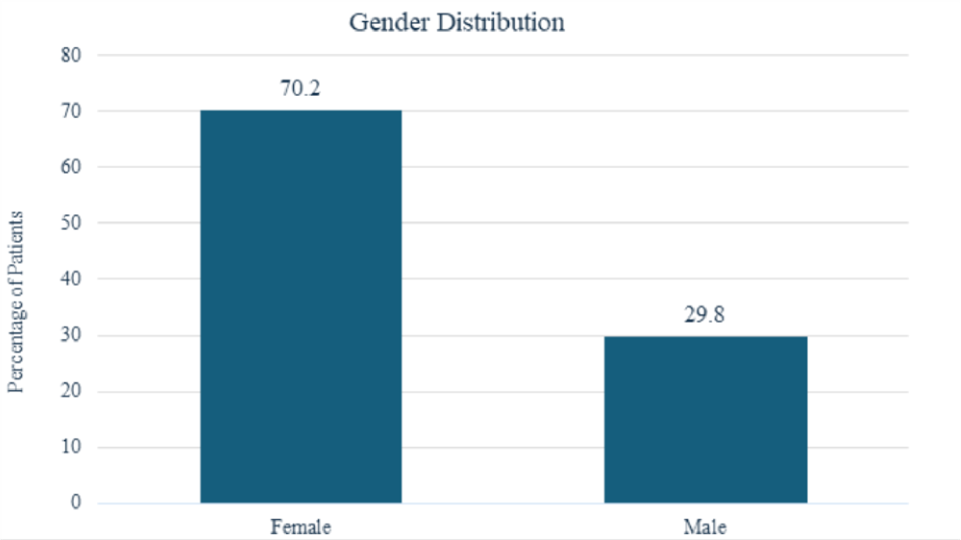

The average age for patients presenting to the ED with behavioral health complaints was 13.86 years with a standard deviation of 2.52 years. The youngest age reported was 2.68 years. Most patients included were biologically female (70.2%) (Figure 2.0). The most common race reported was white (66.1%), and the most common ethnicity was non-Hispanic or Latino (84.9%).

Figure 2: Biologically Assigned Gender.

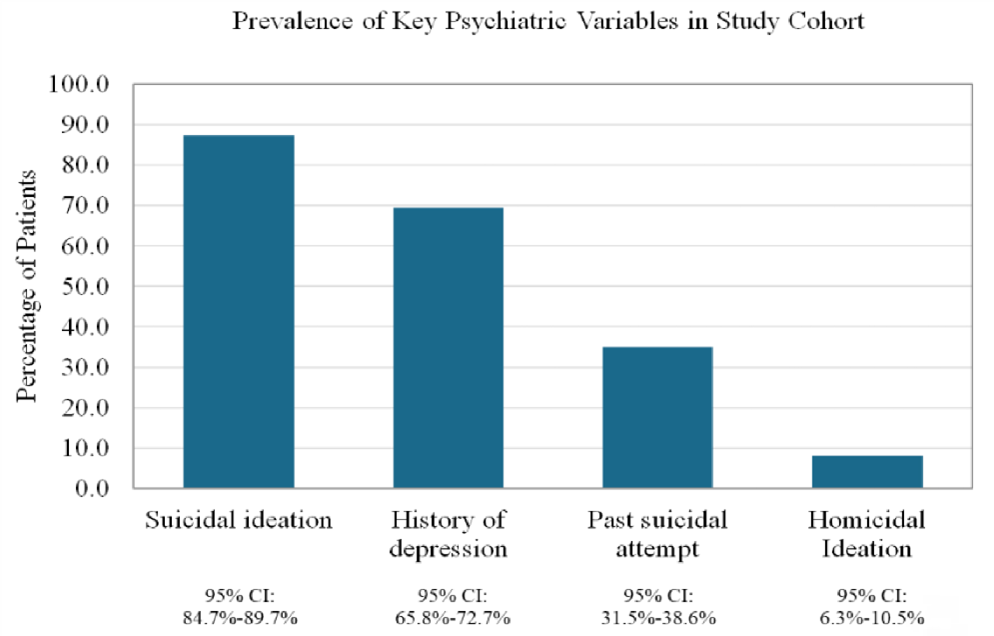

Out of 717 patients, 626 (95% CI, 84.7-89.7) had reported suicidal ideation during the visit, 251 patients (95% CI, 31.5-38.6) had a history of prior suicide attempt, 497 patients (95% CI, 65.8-72.7) documented history of depression, and 59 patients (95% CI, 6.3-10.5) had reported homicidal ideation during the ED visit (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Key Psychiatric Variables.

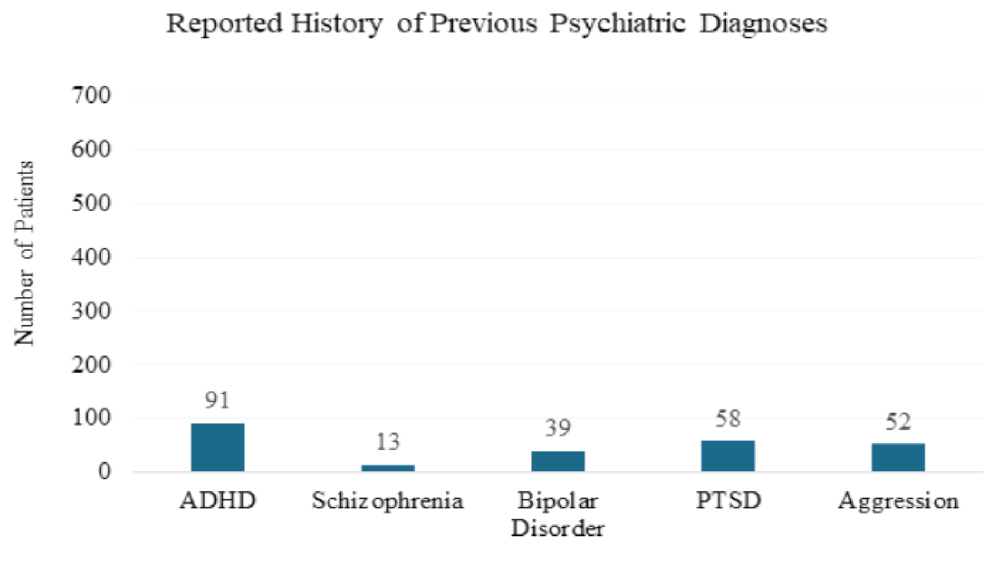

Few patients had a history of previous diagnosed psychiatric diagnosis such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or schizophrenia. Only 91 patients (12.7%) had a diagnosis of ADHD, 13 (1.8%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 39 (5.4%) had bipolar disorder and 58 (8.1%) had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) documented in the charts (Figure 2.2). Also noted was that 4.9% of the total patients (95% CI, 3.4-6.7) had reported gender dysphoria.

Figure 2.2: Reported Psychiatric Diagnoses.

Review of medical records showed that 2.6% of patients (95% CI, 1.6-4.1) had a reported low intelligence quotient (IQ) and 5.4% of patients (95% CI, 3.9-7.4) had documented history of autism spectrum disorder.

Documentation was reviewed for reports of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and 278 patients (38.8%) had documentation of one or more ACE. Twelve percent of patients (95% CI, 9.5-14.3) had Department of Human Services (DHS) involvement documented at some point in their lives and 9.9% of patients (95% CI, 7.81-12.3) had reported personal history of sexual abuse. Emotional abuse was reported in 5% of the patients (95% CI, 3.5-6.9), physical abuse in 3.9% of the patients (95% CI, 2.61-5.6) (Table 1.0).

|

Adverse Childhood Experiences |

% of Patients |

95% CI (%) |

Number of Patients |

|

DHS Involvement |

11.7 |

9.5 - 14.3 |

84 |

|

Sexual Abuse |

9.9 |

7.8 - 12.3 |

71 |

|

Emotional Abuse |

5.0 |

3.5 - 6.9 |

36 |

|

Estranged Parent(s) |

5.0 |

3.5 - 6.9 |

36 |

|

Physical Abuse |

3.9 |

2.6 - 5.6 |

28 |

|

Parental Drug Abuse |

3.8 |

2.5 - 5.4 |

27 |

|

Mental Illness |

2.7 |

1.6 - 4.1 |

19 |

|

Bullying |

2.7 |

1.6 - 4.1 |

19 |

|

Parental Death |

2.2 |

1.3 - 3.6 |

16 |

|

Parental Incarceration |

1.4 |

0.7 - 2.6 |

10 |

Table 1: Adverse Childhood Experiences.

Most patients (93.7%) (95% CI, 91.7-95.4) had lab work done in the ED, with the most common labs ordered being complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel (CMP), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and urine analysis (UA).

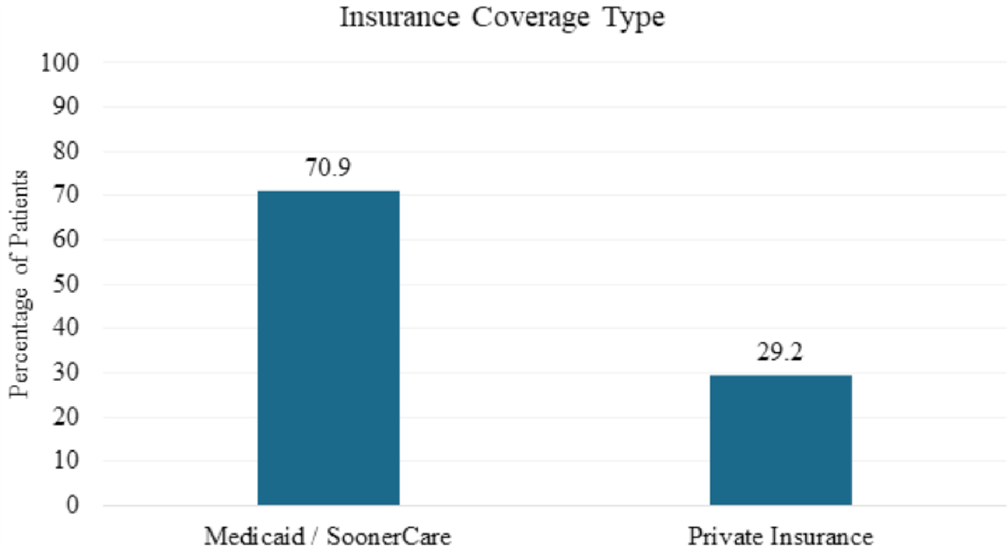

Insurance data was reviewed and 508 patients (70.9%) had Medicaid (government insurance) while 209 patients (29.2%) had private insurance (Figure 3.0).

Figure 3: Insurance Coverage.

The expected bed turnover time per our hospital policy is 120 minutes and arrival to admit time is 180 minutes. A review of our data showed that behavioral health patients stayed in the ED for an average of 33.98 hours (2,038 minutes), which is significantly longer than what is recommended for ED turnover (Table 2.0).

|

Variable |

Characteristic |

Overall |

|

Duration of Stay (Hours) |

Observed |

380 / 717 |

|

Missing |

337 (47.00%) |

|

|

Mean ± SD |

33.98 ± 31.49 |

|

|

Median [IQR] |

22.50 [14.00, 48.00] |

|

|

Range |

(1.00, 192.00) |

Table 2: Length of stay in Pediatric ED.

We reviewed financial data for 5 behavioral health patients with long ED visits (mean stay of 5645 minutes/3.9 days in the ED); the average charges for these patients were $11,268 with an average reimbursement of $767. We compared this to the financial data provided by our hospital administration for patients presenting with medical complaints and noted a stark difference in both ED length of stay and reimbursement. Patients seen with a diagnosis code of unspecified acute otitis media (ICD 10:H66.90) were charged an average of $12,572 with reimbursement of $1,562. Those seen for pneumonia unspecified organism (ICD 10: J18.9) were charged an average of $29,799 with average reimbursement of $1,562; those seen for laceration without foreign body of other part of head (ICD 10: S01.81XA) were charged an average of $12,111 with average reimbursement of $880. Of note the average length of stay for patients presenting for these medical complaints was 261 minutes.

Our local inpatient psychiatric facilities require a Complete Blood Count, Comprehensive Metabolic Panel, Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, urine and serum drug screens along with an Electrocardiogram (EKG) to be completed to ensure there are no underlying medical conditions that the patient has prior to accepting them. This combined panel comes out to a total charge of $2,679 with a direct cost to patients of $713 (Table 3.0). Review of hospital financial records indicated that behavioral health patients’ reimbursement is significantly lower at 7% of the total charges compared to 10% for patients presenting with medical complaints. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) both recommend for laboratory work done for medical clearance to be patient specific. One systematic review done in 2018 found that only 0% to 0.4% of routine laboratory results were clinically significant [12].

|

Service |

Charge in USD |

Direct Cost in USD |

|

Complete Blood Count |

300 |

52 |

|

Complete Metabolic Panel |

967 |

218 |

|

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone |

435 |

47 |

|

Urine Drug Screen |

301 |

36 |

|

Acetaminophen, Ethanol, Salicylate, and Tricyclics |

143 |

55 |

|

EKG |

532 |

306 |

Table 3: Charge for Medical Procedure with Associated Direct Cost.

Local inpatient psychiatric facilities continue to require laboratory work for medical clearance; there are ongoing conversations to help change practice patterns to align with AAP and ACEP recommendations, allowing for improved patient care and significant financial savings for patients and the medical systems.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations, the electronic medical record (EMR) system used at our hospital changed from Meditech to EPIC in June of 2023, during the cross over some medical records were not fully transitioned over, this included but not limited to notes, disposition, consultations and lab work. During extraction of data from the warehouse only records up to September 22nd of 2022 were able to be pulled due to lack of personnel available to help with this study; thus, we were unable to get the dataset completed to December 31st of 2022 as was requested. Accurate ED length of stay could not be obtained for several patients during data extraction. However, after manual review the number of patients with incomplete LOS was decreased to 337. Patients affected were primarily those that were admitted to the hospital for medical management. Another limitation of this study was that it was a single center, retrospective study, involving chart review which could have led to incorrect classification and incomplete data as well as under reporting of social and behavioral factors. Our Pediatric ED is staffed by residents, fellows, faculty and advanced practice providers; all providers have different documenting styles, with some providers charting minimal, pertinent history. Some providers do not enter all billable ICD-10 codes, which further hinders obtaining accurate data for retrospective studies such as this one.

Discussion

This study highlights the increasing prevalence of behavioral health issues in our pediatric and adolescent populations. The yearly increase in the number of patient visits to our ED reflects the national trends and reveals critical gaps in both outpatient and inpatient mental health resources for children and adolescents. High rates of suicidal ideation, prior suicide attempts, depression, and occasional homicidal ideation noted in our patient population emphasizes the need for urgent interventions at both the local and national level. Resources catering to individual needs such as trauma from sexual abuse, domestic violence, parental incarceration and bullying are required. Future studies are required to find the underlying cause of this mental health pandemic to help decrease the incidence.

Prolonged ED boarding, with an average stay of nearly 34 hours, places a significant burden on emergency departments that are not staffed to provide appropriate psychiatric care. The lack of readily available psychiatric resources and consultations contributes to ED overcrowding, patient dissatisfaction, delays in care for other patients, and unnecessarily increased costs with substantial lost revenue. Prolonged boarding leads to decreased bed turnover with prolonged wait times for patients waiting to be evaluated and treated.

Boarding patients in our windowless rooms without structured care has shown to worsen their psychological distress. The inadequacy of behavioral health-specific rooms, only three in our 25-bed ED, demonstrates how our department along with others has not kept pace with the growing demand.

Socioeconomic disparities are also evident as the majority of behavioral health patients rely on Medicaid. These children are at increased risk for mental and behavioral health issues due to social determinants of health, exacerbated by multiple ACEs and a history of abuse and trauma.

Routine laboratory work is unnecessary as proven by previous studies and needs to be catered to the individual patient in the same manner as it is for patients presenting with medical complaints.

The current pattern of prolonged ED stays, and low reimbursement rates results in substantial revenue loss for hospital systems. Addressing these financial inefficiencies will require coordinated efforts between hospital administration and payers to develop reimbursement models that accurately reflect the resources required to manage this population, while simultaneously supporting evidence-based, cost-effective care practices.

In conclusion, behavioral health resources are lacking for the general population with a significant deficiency noted for pediatric patients. This crisis needs to be prioritized by public and private institutions; there is an urgent need for development of more outpatient behavioral health resources and inpatient psychiatric facilities to help decrease the burden on Pediatric Emergency Departments. The hospital systems are losing significant revenue due to minimal reimbursement for lengthy stays and unnecessary laboratory work.

Until further resources and facilities are developed, pediatric ED’s need to implement protocols to promote a calming environment with set routines and schedules for patients to help prevent disorientation and delirium. Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) has developed a comprehensive care plan to help better care for patients while boarding in the ED. Such toolkits should be utilized by all EDs to help improve patient care.

Author Contributions

Statistical experts: Justin Dvorak, PhD and Michael Anderson, PhD served as the statistical experts for this study.

Financial Information Contribution: Brad Jimeson and Robert Hawthorne served as the financial information contributors for this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement: Fatima Sukhera, MD: Writing – original draft preparation, visualization, conceptualization (lead), review & editing.

Ayesha Sajid, BSc: Writing – review & editing.

Jaclyn Urquiola Sorzano, DO: Writing – conceptualization (supporting), review & editing.

Curtis Knoles, MD: Writing – conceptualization (supporting), review & editing, supervision.

Justin Dvorak, PhD: Data curation and formal analysis.

Michael Anderson, PhD: Data curation and formal analysis.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

None of the participating study personnel or investigators have any financial relationships or affiliations to disclose regarding the initiation, conductance, completion, or outcomes of the proposed study. Artificial intelligence was utilized for review of grammatical errors and improving formatting.

References

- Brewer AG, Doss W, Sheehan KM, Davis MM, Feinglass JM (2022) Trends in Suicidal Ideation-Related Emergency Department Visits for Youth in Illinois: 2016-2021. Pediatrics 150: e2022056793.

- Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M, DeGue S, Le VD, et al. (2022) Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness Among High School Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic - Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January-June 2021. MMWR Suppl 71: 16-21.

- Bommersbach TJ, McKean AJ, Olfson M, Rhee TG (2023) National Trends in Mental Health-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Youth: 2011-2020. JAMA 2: 1469-1477.

- Stephenson J (2021). Surgeon General Urges Rapid, Coordinated Response to Mental Health Crisis in US Youth. JAMA Health Forum 2: e214995.

- Joseph A, Mihandoust S, Ardekani MS, Dietrich A, Narasimhan M (2025) RIPCHD.PED Study Group. Evaluating Safety Concerns for Pediatric Mental and Behavioral Health Patients and Providers in the Emergency Department: A Systems Perspective. J Patient Saf.1: S29-S35.

- Slade EP, Dixon LB, Semmel S (2024) Trends in the duration of emergency department visits, 2001-2006. Psychiatr Serv. 61: 878-84.

- Weiss AP, Chang G, Rauch SL, Smallwood JA, Schechter M, et al. (2012) Patient- and practice-related determinants of emergency department length of stay for patients with psychiatric illness. Ann Emerg Med 60: 162-71.

- McEnany FB, Ojugbele O, Doherty JR, McLaren JL, Leyenaar JK (2020) Pediatric Mental Health Boarding. Pediatrics 146: e20201174.

- Janke AT, Nash KA, Goyal P, Auerbach M, Venkatesh AK (2022) Pediatric mental health visits with prolonged length of stay in community emergency departments during COVID-19. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 3: e12869.

- Nicks BA, Manthey DM (2012) The impact of psychiatric patient boarding in emergency departments. Emerg Med Int 2012: 360308.

- Conigliaro A, Benabbas R, Schnitzer E, Janairo MP, Sinert R (2018) Protocolized laboratory screening for the medical clearance of psychiatric patients in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 25: 566-576.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.