Primary GFAP+ Immature Ovarian Teratoma in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Case Report

by Corazon A Ngelangel1*, Jaemelyn F Ramos1, Crystal Lindsey R Manalo2, Melissa A Villamin3

1Asian Cancer Institute, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Philippines

2Department of Internal Medicine, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Philippines

3Department of Internal Medicine, Delos Santos Medical Center, Philippines

*Corresponding Author: Corazon A Ngelangel, Asian Cancer Institute, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Philippines

Received Date: 16 December 2025

Accepted Date: 20 December 2025

Published Date: 23 December 2025

Citation: Ngelangel CA, Ramos JF, Manalo CLR, Villamin MA. (2025). Primary GFAP+ Immature Ovarian Teratoma in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Case Report. Ann Case Report. 10: 2490. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102490

Abstract

The presence of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) together in a 31-year-old female with GFAP+ immature ovarian teratoma metastatic to the lung represents an extraordinarily complex and rare clinical scenario. There are no known published reports describing all four conditions together in a single patient. Additionally, immature ovarian teratomas are rare germ cell tumors, which in this case has somatic transformation to a purely glial-type malignancy contributing to its rarity, pushing rare occurrence of lung metastasis. The patient also has open lumbosacral myelomeningocele and congenital hydrocephalus at birth, and then polycystic ovarian syndrome and asthma.

Keywords: Immature GFAP+ Ovarian Teratoma; Rheumatoid Arthritis; Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; Antiphospholipid Syndrome; Case Report.

Introduction

Immature ovarian teratomas (IOT) are rare malignant germ cell tumors, accounting for less than 1% of all ovarian cancers. They typically affect young women and are histologically graded based on the amount of immature neuroepithelium present [1-3]. Majority of IOTs are diagnosed at early stage (Stage I), with recurrences or metastasis most frequently occurring in high-grade disease. IOTs rarely metastasize to the lung; they spread commonly to abdominal cavity, omentum, or lymph nodes [3].

A rare but clinically significant complication is the somatic transformation of a teratoma, where a distinct, non-germ cell malignancy arises from one of the teratoma's somatic components. This phenomenon is associated with chemotherapy resistance and a poor prognosis. [4] While the most common transformations are sarcomas such as rhabdomyosarcoma, or adenocarcinoma, transformation into a high-grade, glial-predominant malignancy such as glioblastoma-like, is exceptionally rare [5]. Such cases create a dilemma in the diagnostics, as the metastatic disease mimics a new primary tumor like a primary lung or brain cancer and is histologically and immunophenotypically distinct from the original germ cell tumor. This is an IOT case diagnosed Stage IB and then a year after primary treatment, metastatic to the lungs, showing somatic transformation into a GFAP-positive glial malignancy.

At the time of metastatic IOT diagnosis, the patient was also diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), representing an extraordinarily complex and rare clinical scenario. There are no known published reports describing all four conditions together in a single patient; however, clinical and mechanistic relationships exist between some of these conditions.

Case Presentation

This is a 31-year-old wheelchair bound single non-smoker female with open lumbosacral myelomeningocele and congenital hydrocephalus at birth, with excision, repair, and a right parietal VP shunt, respectively, in 1995. She has tethered cord syndrome diagnosed in 2009, status-post repair, resulting in a chronic neurogenic bladder requiring intermittent self-catheterization. She also has polycystic ovarian syndrome, and childhood asthma. She has allergy to seafoods, eggs, peanut, diphenhydramine. She has a family history of ovarian cancer (first degree cousin) and lupus (distant maternal relatives).

In October 2023, she noted a palpable pelvic-abdominal mass. Abdominal CT scan (January 2024) revealed a 10.8 x 15.5 x 14.8 cm complex mass. There was elevated CA-125 (53.6 u/ mL) and LDH (347 U/L). On 8 February 2024, she had left salpingo-oophorectomy, and then TAHBSO on 11 April 2024, for IOT, bilateral, Stage 1B. From May to July 2024, she received three cycles of adjuvant BEP (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin) chemotherapy. She had bleomycin-induced tachycardia. Following therapy, her tumor markers normalized, CA-125 of 12 U/mL.

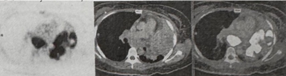

August 2025 chest CT scan identified two new left lung lesions. with normal CA-125 and AFP, but with high LDH (339 U/L). PET-CT scan (19 September 2025) showed a l10.4 x 5.9 x 8.3 cm heterogeneously enhancing, hypermetabolic soft tissue mass in the left upper lung lobe, causing severe narrowing of the distal left main bronchus and encasing the left lobar arteries. Another 3.6 cm mass was noted in the left lower lung lobe. Progression of hypermetabolic subcarinal, paratracheal, and para-aortic lymph nodes, was worrisome for nodal metastasis (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Axial PET-CT scan correlating the intense FDG-avidity on the PET slice (left) with the large, heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass seen in the left upper lobe (middle and right).

Biopsy (30 September 2025) showed metastatic IOT. Immunohistochemistry indicated GFAP (diffuse) positive, S100 (patchy) positive, and negative for SALL4 (germ cell), PAX8 (Mullerian/GYN), TTF-1 (lung), p40 (squamous), CK7/CK20 (epithelial), and Synaptophysin (neuroendocrine). The diffuse GFAP positivity and SALL4 negativity, confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic IOT with somatic transformation into a high-grade glial malignancy.

At this time, she was also diagnosed to have rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), stabilized under the care of a rheumatologist, managed with hydroxychloroquine and aspirin.

Figure 2: Whole-body PET scan demonstrating the extent of the intensely hypermetabolic metastatic disease in the left chest and mediastinal lymph nodes

Patient underwent radiation to debulk the lung mass, which showed compression of midline chest organs. She is undergoing palliative drug therapy, including temozolomide.

Discussion

This case presents a rare and aggressive evolution of an immature ovarian teratoma. The key finding is the metastatic recurrence of the IOT, not as a typical germ cell tumor (GCT), but as a somatically transformed, GFAP-positive glial malignancy. The negativity of SALL4, PAX8, and TTF-1 effectively ruled out a recurrent GCT, a new Mullerian primary, or a primary lung adenocarcinoma, respectively. The diffuse GFAP positivity pointed to a neural/glial lineage.

Somatic transformation in GCTs is a known mechanism of chemotherapy resistance and is reported in a small percentage of cases, often involving sarcomatous or carcinomatous differentiation. These transformed elements are histologically distinct from the GCT component and typically have a much poorer prognosis as they are not sensitive to standard platinumbased GCT regimen. Transformation into a high-grade glial tumor, essentially a central nervous system-type malignancy metastatic to the lung, is a rare variant on Gliomatosis peritonei with somatic transformation to high-grade glioma in metastatic immature ovarian teratoma [6]. This diagnosis is particularly challenging, as the primary teratoma is, by definition, composed of tissues from all three germ layers, including immature neuroepithelium. However, the malignant, metastatic, and GFAP-positive nature of the lung mass represents a true somatic transformation and not simply a mature teratoma component.

The diagnosis of a metastatic, GFAP-positive glial malignancy in this patient, one year after treatment for a Stage 1B IOT, places her in a rare clinical category. This somatic transformation is an aggressive entity that fundamentally alters the treatment paradigm and prognosis. The therapeutic dilemma is whether to treat the cancer as a refractory germ cell tumor or as the new, transformed somatic malignancy.

Standard management for immature ovarian teratoma usually involves complete surgical resection followed by platinum-based chemotherapy (typically bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin). However, in rare cases with high-grade glial components, especially when the tumor is refractory or recurs temozolomide, an alkylating agent effective against high-grade gliomas, has been considered. Temozolomide has been used experimentally for high-grade, immature GFAP-positive glial ovarian teratoma, particularly when the disease acts similarly to aggressive gliomas or progresses despite standard treatment [7,8].

Inadvertently, the patient is simultaneously diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and immature ovarian teratoma representing an extraordinarily complex and rare clinical scenario. There are no known published reports describing all four conditions together in a single patient; however, clinical and mechanistic relationships exist between some of these conditions.

SLE and APS co-occur at relatively high rates, especially in women of childbearing age. These overlaps increase risks for thrombotic events, obstetric complications, and multi-organ autoimmune effects. Typical complications of SLE and APS include arterial/ venous thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, livedo reticularis, and potential multiorgan damage [9-11]. Hydroxychloroquine is often recommended for SLE patients with positive antiphospholipid antibodies due to its thrombo-protective effect. Low-dose aspirin may be indicated for primary thrombosis prevention in high-risk APS profiles, especially in the background of SLE or multiple autoimmune syndromes. Immunosuppressants and biologic agents are often employed, selected and dosed according to disease activity and risk profile.

APS often occurs secondary to SLE, affecting up to 40% of SLE patients, and to a lesser extent is associated with RA [9,10,12]. Many patients with one autoimmune disease are at greater risk for another, and rare overlap syndromes (SLE/RA/APS) have been described [11]. APS, SLE, and RA are all systemic autoimmune diseases characterized by loss of self-tolerance, chronic inflammation, and production of autoantibodies [13,14]. The coexistence of SLE, RA, and APS can present as “rhupus” with frequent positivity for antiphospholipid antibodies and, in many cases, secondary APS. Around 30%-50% of patients diagnosed with one connective tissue disease (e.g., SLE, RA, APS) develop another overlapping autoimmune illness, altering clinical course and treatment response. Simultaneous occurrence exacerbates risk for both inflammatory and thrombotic manifestations, such as erosive polyarthritis, renal involvement, and recurrent thrombosis.

Common immune pathways involve dysregulated B-cell and

T-cell activation, genetic susceptibility (such as HLA risk alleles), and environmental triggers [13, 14]. These conditions can cooccur due to a background of poly-autoimmunity where a person’s immune system is prone to targeting multiple organ systems by diverse autoantibodies [13].

The presence of APS and SLE in a patient with RA increases risk for thrombotic complications and potential end-organ damage; the diagnosis of an immature teratoma adds further complexity regarding immunosuppression, surgical risk, and surveillance for paraneoplastic phenomena [9,10,15,16]. There is evidence of shared autoimmune mechanisms connecting APS, SLE, and RA, but the simultaneous occurrence of these with an immature ovarian teratoma is extremely rare and implies complex immunological interactions rather than a single unifying autoimmune pathogenesis.

Immature ovarian teratoma is a rare malignant germ cell tumor, often affecting younger women [15,17-19]. Ovarian teratomas especially mature ones are recognized triggers of autoimmune neurological conditions (notably anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis), and can rarely provoke hematologic autoimmunity (e.g., autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia). There are reports of paraneoplastic phenomena linked to ovarian tumors, including the development or exacerbation of APS and autoimmune cytopenias [15-16]. The suspected mechanisms involve aberrant immunogenic content within the teratoma (e.g., neural or hematopoietic tissues) leading to breakdown in immune tolerance and epitope spreading [15, 17,19, 20].

Immature ovarian teratoma itself is not classically an autoimmune disease, but ovarian tumors (particularly teratomas) can trigger paraneoplastic autoimmune syndromes, including autoimmune encephalitis and even hematologic cytopenias [2023]. The mechanism involves immune responses against tumor antigens some of which mimic or cross-react with self-antigens breaking immune tolerance and potentially amplifying systemic autoimmunity [21]. Invasion or inflammation caused by a teratoma can lead to immune cell migration and the expansion of autoreactive T-cells beyond the tumor, which is a known trigger for systemic autoimmune or paraneoplastic syndromes [13, 21].

While no literature documents all four diagnoses in a single patient, it is biologically plausible for a predisposed individual to develop multiple autoimmune diseases (poly-autoimmunity) and simultaneously harbor an ovarian teratoma. The malignancy itself, or its paraneoplastic immune perturbations, may trigger or worsen autoimmune manifestations, including APS [15-16]. No case series or reports discuss the exact intersection of APS, RA, SLE, and immature ovarian teratoma in one patient to date, but the medical literature supports the plausibility of severe, multiautoimmune overlap and paraneoplastic immune syndromes in a young female patient.

While SLE, RA, and APS may develop on a background of generalized autoimmunity, an immature ovarian teratoma may act as a catalyst (through paraneoplastic immune mechanisms) that escalates or unmasks broader immune dysfunction. No single unified mechanism has been identified to connect all four diseases beyond the generalized risk of immune dysregulation, autoantibody production, and possibly paraneoplastic enhancement of autoimmune pathways. The co-occurrence points to a “perfect storm” of genetic, immunological, and environmental contributors to autoimmunity rather than a single molecular pathway or defect.

In summary, shared dysregulation of humoral and cellular immunity likely links APS, SLE, and RA, while a paraneoplastic effect from the ovarian teratoma could amplify or diversify immune responses, but no single, specific autoimmune mechanism unifies all four conditions simultaneously [13, 21]. This case of metastatic immature ovarian teratoma highlights the critical, though rare, phenomenon of somatic transformation into a GFAPpositive glial malignancy, which can drive immune amplification and be instrumental in the genesis of paraneoplastic syndromes. However, classic rheumatologic autoimmune diseases - SLE, RA, APS - can rarely occur alongside malignancy, including ovarian cancer, as part of a paraneoplastic process, but their association with ovarian teratoma specifically is extremely uncommon and not typical of their recognized paraneoplastic spectrum.

Declaration

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate: A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal. With the patient’s consent, ethical approval was given.

Consent for publication: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Availability of supporting data: The patient’s medical record is available at the hospital for review.

Competing interests: There is no competing interest on behalf of the authors in reporting this case:

Funding: There is no institutional fund provided for this case report.

Author’s information and contributions: All authors are doctors of Asian Hospital and Medical Center and members of the multidisciplinary team who took care of the patient and contributed to the case report writing and review.

Acknowledgements: We thank our patient for consenting to present her clinical history to the scientific audience at large.

References

- Raj R, Ranjan R, Chakrabarty S. (2024). Immature teratoma of the ovary: a series of rare cases and review of literature. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 16: 631-637.

- Errami L, Douzi A, Lamzouri O, Taheri H, Saadi H, et al. (2024). Immature ovarian teratoma in a 20-year-old woman: a case report. Journal of International Medical Research. 52: 1-6.

- Marino G, Negri S, Testa F, Corti J, Giuliani D, et al. (2025). Immature teratoma of the ovary: a narrative review. Cancers. 17: 3041-3055.

- Gershenson DM. (2020). Management of ovarian germ cell tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 38: 1055-1064.

- Lee J, Kim HS, Kim K, Kim H, Kim J, et al. (2021). Somatic transformation of ovarian immature teratoma into a high-grade neuroepithelial tumor: a case report. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 40: 281-286.

- Ahmed N, Sadia S, Riaz S, Hafeez S, Sarfraz T. (2022). Gliomatosis peritonei with somatic transformation to high-grade glioma in metastatic immature ovarian teratoma. Gynecologic Oncology Reports. 42: 101035-101040.

- Ahoussougbemey Mele A, Sanak S, Ellis E, Green A. (2022). Immature teratoma with metastatic gliosis. Cureus. 14: 22748-22755.

- Kim G, Estrada P, Nilforoushan N. (2018). High-grade glioma arising in an ovarian immature teratoma. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 149: 113-118.

- Toska I, Rapushi E, Shkurti R, Mitre A. (2025). Antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. International Journal of Biomedicine. 15: 598-600.

- Shrateh ON, Jobran AWM, Amoori A. (2023). Rare diagnosis of coexistent antiphospholipid syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus in a male patient with successful management: a case report. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 85: 1983-1986.

- Chen HH, Lin CH, Chao WC. (2021). Risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study. Frontiers in Medicine. 8: 654791-654799.

- Sawlani A, Masood R, Bai S, Anwar A. (2023). Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome in a male patient: a case report. Clinical Case Reports International. 7: 1614-1620.

- Wang V, Walsh JA, Zell J, Verrilli LE, Letourneau JM, et al. (2025). Autoimmune disease is increased in women with primary ovarian insufficiency. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 110: 2614-2620.

- García-Carrasco M, Mendoza Pinto C, Jiménez Hernández C, Solís Poblano JC, Etchegaray Moraleset I, et al. (2013). Antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside. 1: 1-20.

- Althobati S, Assinnari A, Alhardi M, Kurdi R. (2025). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with ovarian teratoma in a 13-year-old: a rare paraneoplastic presentation. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 13: 17004431700450.

- Ruffatti A, Aversa S, Del Ross T, Tonetto S, Fiorentino M, et al. (1994). Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome associated with ovarian cancer: a new paraneoplastic syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology. 21: 21622163.

- Schiavi MC, Manganelli F, Morgani C, Cignini P, Yacoub V, et al. (2021). Mature ovarian teratoma: neurological implications in a young woman. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021: 30855593085565.

- Khalife D, Nassif J, Khalil A, Ghazeeri G, Taher A. (2018). Ovarian teratoma: yet another cause of immune thrombocytopenia. International Journal of Women’s Health. 10: 567-570.

- Felemban AA, Rashidi ZA, Almatrafi MH, Alsahabi JA. (2019). Autoimmune hemolytic anemia and ovarian dermoid cysts in pregnancy. Saudi Medical Journal. 40: 397-400.

- Medina Luna A, Caamal Torres OCA, Magaña Dávalos RA, Vidal Valderrama CE. (2025). Anti-NMDA encephalitis associated with a mature ovarian teratoma: a compelling case report. International Journal of Medical Students. 12: 333-338.

- Perez-Bucio C, Behere A, Landegren N. (2025). Mechanisms of autoimmune-mediated paraneoplastic syndromes: immune tolerance and disease pathogenesis. Frontiers in Immunology. 15: 16089341608942.

- Panzer J, Dalmau J. (2011). Movement disorders in paraneoplastic and autoimmune disease. Current Opinion in Neurology. 24: 346-353.

- Chatterjee M, Hurley LC, Tainsky MA. (2017). Paraneoplastic antigens as biomarkers for early diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology Reports. 21: 37-44.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.