Preventable Gallbladder Cancers Arising from Untreated Gallstones in India

by Zaina Waris1, Kaustav Mondal1, Swagata Naskar1, Srijan Mazumdar2, Chandan Chatterjee2, Abhijit Chowdhury1-3, Bitan Chatterjee4, Ranajoy Ghosh5, Rajib Sarkar5, Megan P. Hitchins6, Shalini Datta1,6*#

1John C Martin Centre for Liver Research and Innovations (jcmlri.edu.in), Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences (IILDS), Sitala (East), Jagadishpur, Sonarpur, 24 Pgs(S), Kolkata, West Bengal, India

2Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences, Sitala (East), Jagadishpur, Sonarpur, 24 Pgs(S), Kolkata, West Bengal, India

3Liver Foundation, West Bengal, Chatterjee International Centre, 33 A J N Road, West Bengal, India

4Department of Surgery, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research (IPGME&R), 244, A. J. C. Bose Road, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

5Department of Gastroenterology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research (IPGME&R), 244, A. J. C. Bose Road, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

6Department of Cancer Epidemiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, Florida, USA

*Corresponding author: Shalini Datta, Department of Basic Science and Disease Biology, John C Martin Centre for Liver Research and Innovations, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

#Visiting faculty, Department of Cancer Epidemiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, Florida, USA

Received Date: 03 December 2025

Accepted Date: 09 December 2025

Published Date: 11 December 2025

Citation: Waris Z, Mondal K, Naskar S, Mazumdar S, Chatterjee C, et al. (2025) Preventable Gallbladder Cancers Arising from Untreated Gallstones in India. Ann Case Report. 10: 2470. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102470

Abstract

Background: Gallstones are a major risk factor for gallbladder cancer (GBC), especially in India where untreated cholelithiasis often progresses to malignancy through chronic inflammation. Preventive measures remain underused in high-incidence regions.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed ten patients from West Bengal, India, who developed stage IV GBC following untreated gallstones. Demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic data were reviewed to identify duration between gallstone and GBC diagnoses and delays in intervention.

Results: Of the 10 cases, seven were female and mean age was 56.8 years. The gallstones in nine cases were first detected incidentally by ultrasonography or CT. The duration of untreated gallstones until the diagnosis of GBC ranged from 7 to 332 (mean 106) months. Socioeconomic barriers contributing to delayed surgery included lack of awareness, financial limitations, and poor access to healthcare. GBC presented with abdominal pain, vomiting, and jaundice. Half of the patients died within three months of their cancer diagnosis.

Discussion: This retrospective observational study shows the natural history of prolonged untreated gallstones can evolve into advanced GBC within a mean duration of 8.8 years. Timely cholecystectomy in high-risk persons may prevent malignant transformation. Strengthening awareness and preventive surgery programs in endemic areas could substantially reduce mortality from preventable GBC.

Keywords: Cholelithiasis; Gallbladder cancer; Cholecystectomy

List of Abbreviations: CEA: Carcinoembryonic Antigen; CECT: Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography; CT: Computed Tomography; dx / Dx: Diagnosis; GBC: Gallbladder Cancer; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; IL-8: Interleukin-8; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MRCP: Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography; OS: Overall Survival; PBCR: Population-Based Cancer Registry; USG: Ultrasonography; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a deadly cancer that is considerably more common in endemic areas such as northern India and Chile, where incidence is 10-20 times higher than the worldwide average [1,2]. Cholelithiasis (gall stones) has been causally linked to GBC in 70-85% of cases via chronic inflammatory cascades that lead to a metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence when untreated [3-5]. With preneoplastic alterations like metaplasia (prevalence 32–48%) and dysplasia (1-16%) detected within 5-15 years postcholelithiasis onset, this histological progression usually happens over 15-20 years [6]. Long-term gallstone persistence (>10 years; odds ratio 4-23.8), calculi larger than 3 cm, genetic predispositions (including ABCG8, ABCB1/4 polymorphisms, and variations in DNA-repair, apoptotic, and inflammatory pathway genes), obesity, multiparity, and microbial colonization (including Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli) are contributing factors [7-11]. Despite the relatively small absolute risk for GBC (0.3-3%) in patients with cholelithiasis, the population-attributable proportion in hyperendemic areas approximates 80%, underscoring cholelithiasis as a modifiable etiological determinant [12,13].

Even though prophylactic cholecystectomy (surgical removal of gall stones) for symptomatic or large asymptomatic cholelithiasis has the potential to diminish GBC mortality by 80-90%, adoption is still below optimum in rural India with limited clinical resources and because of limited public awareness and financial constraints [14,15]. In situations with limited resources, universal screening is not feasible; however, prompt detection may be facilitated by selective ultrasonographic surveillance and serological profiling of inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-8, C-reactive protein) [4]. In West Bengal, GBC is a major burden, accounting for 7.4% of all female cancers in the Population Based Cancer Registry of Kolkata (2012), ranking fourth after breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers [16]. Indian national registry data have shown a rising female incidence of GBC since 2004 and a geographic concentration along the Gangetic belt, including West Bengal [17]. The current retrospective case series, which originates from West Bengal, a high-burden region where GBC accounts for approximately 6% of cancers, provides real-world evidence of the cholelithiasis-to-GBC continuum in untreated patients, supporting increased awareness and preventative surgical techniques to prevent this preventable cancer [18-20].

Methods

The medical records of ten patients diagnosed with metastatic GBC due to untreated cholelithiasis, identified at The Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research (IPGMER), Kolkata, and Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences, Sonarpur, West Bengal between December 2024 to May 2025, were reviewed in this study, which is a retrospective observational case series typical of descriptive epidemiological inquiry. The study outlines the phenotypic and temporal characteristics of disease evolution using a descriptive, non-interventional design that excludes comparator cohorts and therapeutic treatments. Eligibility requirements were a ≥1-year untreated gap, preceding imaging-verified cholelithiasis Ultrasonography (USG), Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and histological confirmation of stage IV GBC. The variables that were extracted included demographic information (age, sex), first cholelithiasis diagnosis method and time, first symptoms, length of time untreated, diagnostic symptoms, intervention barriers, and prognosis outcomes as of August 30, 2025. An Institutional Review Board sanction was obtained. Descriptive measurements, such as averages, ranges, and frequencies, were computed; inferential analytics were precluded by the constrained sample dimension. Chronological fidelity was validated via corroboration of archival histories and radiographic documentation [21].

Results

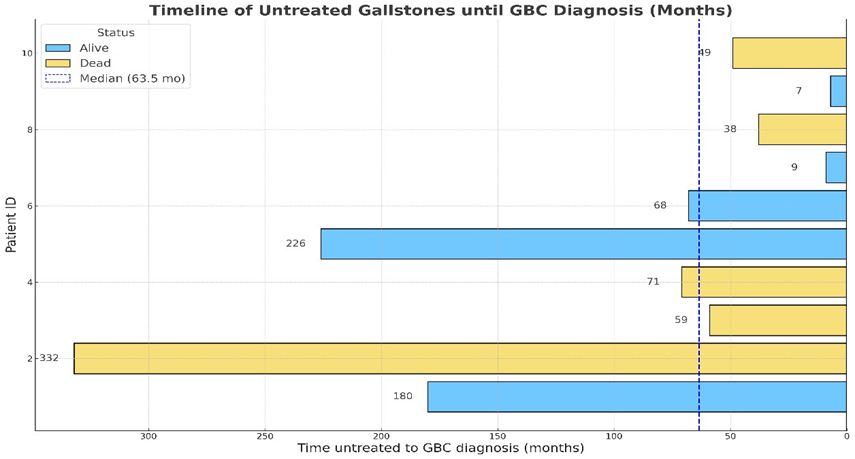

The case series comprised 10 subjects (7 women, 3 men; mean age 56.8 years, range 43-80 years) from semi-urban and rural areas of West Bengal (e.g., South 24 Parganas, Howrah, Bankura) (Table 1). Cholelithiasis presented asymptomatically at the onset in nine of the cases, with only two patients reporting initial symptoms. The untreated interval between initial diagnosis of cholelithiasis and subsequent presentation with gallbladder cancer ranged from 7 to 332 months, with a median of 68.5 months (mean 105.9 months, ~8.8 years) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of untreated cholelithiasis prior to gallbladder cancer (GBC) diagnosis among 10 patients from West Bengal, India.

Each horizontal bar represents one patient, with duration of untreated gallstones (in months) prior to the initial diagnosis of GBC solid black line at T=0 to demarcate this as the important time point shown on the x-axis. Bars are color-coded by survival status as of August 31, 2025: light blue indicates patients alive, and light yellow indicates deceased. A dashed vertical line denotes the median untreated interval (63.5 months) following the detection of gall stones to the diagnosis of GBC.

|

Patient ID |

Age (y) at GBC Dx |

Sex |

District |

Asymptomatic /Symptomatic |

Initial Mode of Detection |

Time Untreated to GBC Dx (months) |

Mode of detection in recent time |

Reason for visiting the doctor recently |

Vital Status/ Overall Survival (OS) (months) censored on 31st Aug 2025 |

|

1 |

74 |

F |

South 24 Pargana |

Asymptomatic |

MRI |

180 |

MRCP |

Abdominal pain, vomiting, Jaundice |

alive |

|

2 |

54 |

F |

Kolkata |

Asymptomatic |

USG |

332 |

CECT |

Jaundice |

17 |

|

3 |

48 |

F |

Howrah |

Asymptomatic |

USG |

59 |

MRCP |

Jaundice |

18 |

|

4 |

43 |

M |

Bankura |

Symptomatic |

USG |

71 |

MRCP |

Abdominal pain, vomiting |

17 |

|

5 |

47 |

M |

Howrah |

Asymptomatic |

USG |

226 |

MRI |

Abdominal pain |

alive |

|

6 |

80 |

F |

Burdwan |

Asymptomatic |

CT |

68 |

CT |

Abdominal pain, vomiting |

alive |

|

7 |

55 |

F |

South 24 Pargana |

Symptomatic |

USG |

9 |

USG + CECT |

Abdominal pain, vomiting |

alive |

|

8 |

62 |

M |

Purba Bardwan |

Asymptomatic |

CT |

38 |

USG |

Abdominal pain, vomiting, Jaundice |

5 |

|

9 |

49 |

F |

Birbhum |

Asymptomatic |

USG |

7 |

USG + CT + MRI |

Fever, abdominal pain |

alive |

|

10 |

56 |

M |

South 24 Pargana |

Asymptomatic |

USG |

49 |

USG |

Abdominal pain, vomiting, Jaundice |

2 |

Table 1: Clinical characteristics and outcomes of ten patients who developed stage IV gallbladder cancer (GBC) following long-standing untreated cholelithiasis in West Bengal, India.

Summary of demographic data, initial presentation, duration of untreated gallstone persistence until GBC diagnosis, recent detection modalities, reasons for medical consultation, and overall survival (OS) status. “Time untreated to GBC diagnosis” denotes the interval between initial imaging detection of gallstones (ultrasonography [USG], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], or computed tomography [CT]) and subsequent diagnosis of GBC. “Vital Status/Overall Survival (OS)” reflects patient status censored on 31 August 2025.

USG accounted for the initial detection in six cases, CT scan in two and MRI in two. Informational gaps accounted for the obstacles to cholecystectomy in seven cases, followed by financial burdens in two cases, poor access to healthcare in one, and clinical oversight in another [22]. Based on multimodal imaging (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in four cases, contrast-enhanced CT in two cases, composite USG/CT/MRI), GBC diagnoses occurred between December 2024 and May 2025, consistently confirming stage IV dissemination.

Advanced disease was supported by symptom profiles that included widespread abdominal pain and vomiting in eight cases, jaundice in half of cases, and pyrexia in one case. Although prior imaging indicated chronicity, gallstone diameters >3 cm were documented in only half of the cases [8]. Prognostic indices were poor: Half of the patients died within 1-3 months post-diagnosis (June–August 2025), while the remaining survivors required palliative support as of August 30, 2025 [19]. These findings highlight both the heterogeneity of latency periods and the rapid downhill course once symptoms emerge. Notably, even patients with relatively short untreated intervals (<12 months) progressed to advanced disease, underscoring the urgent need for early intervention.

Discussion

This case series provides the first empirical timelines in an indigenous Indian paradigm, enabling unique longitudinal documenting of cholelithiasis-mediated transition to stage IV GBC among 10 West Bengal residents [19,23]. With shortened trajectories (1-6 years in 7 out of 10 patients), the mean untreated interval of 8.8 years (range 1-28 years) is consistent with existing literature suggesting a 5-20-year latency for metaplasia-dysplasiacarcinoma sequelae [24-26]. The findings in these 10 cases suggest an accelerated oncogenesis in genotypically or phenotypically vulnerable subpopulations, such as residents of the Gangetic basin [6,20,13]. The majority of the case series were women, who resembled the demographics of Indian GBC, where cholelithiasisrelated inflammatory diatheses are exacerbated by estrogenic effects and gestational parity [12, 22]. These findings reflect global patterns, where gallstones increase GBC risk by 0.3-3% but account for 80% of cases in high-risk areas [13, 19, 20].

GBC develops slowly, often only presenting symptomatically, e.g. with jaundice or abdominal pain at advanced disease stages, with a 50% death rate soon after clinical diagnosis and a 5 year survival rate of only about 2% for advanced metastatic disease highlights the need for early prevention [19, 27]. Prior studies show that carefully performed prophylactic cholecystectomy for gallstones larger than 3 cm or that are present for over 5 years can reduce mortality by 80-90% [14,15,11]. To prevent gallbladder cancer in resourcelimited areas like West Bengal, community-based efforts should focus on raising awareness about symptoms, using cost-effective ultrasound screening for high-risk groups (such as women over 40 with gallstones), and providing affordable access to surgical removal. Encouraging regular doctor visits and checkups at nearby government hospitals or health centers is crucial to overcome educational and financial barriers [3]. Excisional therapies may be accelerated by integrating GBC risk categorization into cholelithiasis care, supplemented by inflammatory biomarker surveillance [4]. Recent evidence also suggests that peri-operative chemotherapy may improve outcomes for advanced GBC, though prevention remains critical given the poor prognosis [27].

This study has inherent limitations, including a restricted sample size, retrospective provenance, and lacunae in genomic profiling or gallstone mensuration. While prospective expansive inquiries would provide the optimal scientific design, they are largely impracticable due to the long follow-up required and the likelihood of substantial patient attrition. Moreover, such non-interventional studies would raise ethical concerns, as withholding treatment in high-risk gallstone carriers would be indefensible given the established natural history of disease progression from gall stone etiology to GBC. In this context, the present study assumes significant value by offering real-world longitudinal insights that directly inform prevention-oriented public health and clinical strategies, motivating a paradigm shift toward preventative elimination in hyperendemic domains to attenuate GBC lethality [21,23].

In conclusion, the initial case series from West Bengal supports the inevitable progression from untreated cholelithiasis to advanced GBC over a period of 1-28 years. This progression can be interrupted with preventative cholecystectomy, supported by various awareness strategies and socioeconomic factors that mitigate [14,15, 22]. In endemic areas, GBC is transformed from an undetected fatality to a treatable illness by clinicians and policymakers emphasizing patient education and prompt intervention [19, 20].

Ethics, Consent to Participate, and Consent to Publish declarations

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences (IILDS), (HREC Approval #IILDS/2024-R38) and ratified by JCMLRI and IPGMER. Moffitt Cancer Center did not have access to private health information. All participants included in the study gave their written informed consent including consent for publication. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Declaration

This research received no external funding.

Authors’ contributions

Z.W, K.M, S.N participated in collecting the clinical data. S.M, C.C, A.C, B.C, R.G, R.S clinically reviewed the cases. S.D and M.P.H wrote and edited the manuscript. S.D and M.P.H were involved in data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients and their families for their trust, cooperation, and consent to share their clinical information, which made this study possible. We also acknowledge the medical and nursing staff of the Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research (IPGMER), Kolkata, and the Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences (IILDS).

References

- Diehl AK. (1983). Gallstone size and the risk of gallbladder cancer. JAMA. 250: 1422-1424.

- Nervi F, Duarte I, Gómez G, Rodríguez G, Del Pino G, et al. (1988). Frequency of gallbladder cancer in Chile, a high-risk area. Int J Cancer. 41: 657-660.

- Sheth S, Bedford A, Chopra S. (2000). Primary gallbladder cancer: recognition of risk factors and the role of prophylactic cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol; 95: 1402-1410.

- Lazcano-Ponce EC, Miquel JF, Muñoz N, R Herrero, C Ferrecio, et al. (2001). Epidemiology and molecular pathology of gallbladder cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 51: 349-364.

- Wistuba II, Gazdar AF. (2004). Gallbladder cancer: lessons from a rare tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 4: 695-706.

- Wistuba II, Gazdar AF. (2004). Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 112: 815-816.

- Roa I, Ibacache G, Muñoz S, de Aretxabala X. (2014). Gallbladder cancer in Chile: pathologic characteristics of survival and prognostic factors analysis of 1,366 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 141: 675-682.

- Mohandas KM, Patil PS. (2006). Cholecystectomy for asymptomatic gallstones can reduce gall bladder cancer mortality in northern Indian women. Indian J Gastroenterol. 25: 147-151.

- Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, LC Sakoda, et al. (2007). Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer. 97: 1261-1266.

- Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Kumar A, Mittal B. (2011). Gallbladder cancer predisposition: a multigenic approach to DNA-repair, apoptotic and inflammatory pathway genes. PLoS One. 6: e16449.

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA. (2012). Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver. 6: 172-187.

- Mathur AV. (2015). Need for prophylactic cholecystectomy in silent gall stones in North India. Indian J Surg Oncol. 6: 251-255.

- Schmidt MA, Marcano-Bonilla L, Roberts LR. (2019). Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and genetic risk associations. Chin Clin Oncol. 8: 31.

- Unisa S, Jagannath P, Dhir V, Khandelwal C, Sarangi L, et al. (2011). Population-based study to estimate prevalence and determine risk factors of gallbladder diseases in the rural Gangetic basin of North India. HPB (Oxford). 13: 117-125.

- Dutta U. (2019). Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer in India. Chin Clin Oncol. 8: 41.

- Indian Council of Medical Research–National Centre for Disease Informatics and Research (ICMR–NCDIR). Profile of Cancer and Related Factors: West Bengal. National Cancer Registry Programme Fact Sheet, 2012. Accessed September 16, 2025.

- Phadke PR, Mhatre SS, Budukh AM, Dikshit RP. (2019). Profile of gallbladder cancer in India. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 40: 90-93.

- Boekstegers F, Marcelain K, Barahona PC, Muller B, De Toro G, et al. (2020). ABCB1/4 gallbladder cancer risk variants identified in India also show strong effects in Chileans. Cancer Epidemiol; 65: 101643.

- Mhatre S, Rajaraman P, Chatterjee N. (2020). Mustard oil consumption, cooking method, diet and gallbladder cancer risk in high- and low-risk regions of India. Int J Cancer. 147: 1621-1628.

- Yadav V, Kilambi R, Sharma R, Mohpatra N, Sastuturkar SV, et al. (2025). Radiocarbon dating of gallstones for timeline of formation, dormancy analysis, and correlation with chemical/microbial composition: a pilot study on gallstone geobiology. J Gastrointest Surg. 29: 101937.

- Dutta EK, Lewis MG, Albert S. (2022). Risk factors associated with gall bladder cancer in high incidence areas in India: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 12: e056849.

- Halaseh SA, Halaseh S, Shakman R. (2022). A review of the etiology and epidemiology of gallbladder cancer: what you need to know. Cureus. 14: e28260.

- Hundal R, Shaffer EA. (2014). Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Liver Dis; 18: 205-217.

- Segovia-Lohse HA, Cuenca-Torres OM, Espinoza-Espinoza LA. (2013). Prevalence and sequence of metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma of the gallbladder: a single-centre retrospective study. Cir Esp; 91: 375-381.

- Khan MR, Raza SM, Khan M. (2011). Gallbladder intestinal metaplasia in Pakistani patients with chronic cholecystitis. J Surg Res; 171: 217221.

- Dutta A, Mungle T, Chowdhury N. (2023). Characteristics and outcomes of gallbladder cancer patients at the Tata Medical Center, Kolkata 2017-2019. Cancer Med; 12: 9293-9302.

- Patkar S, Patel S, Gupta A. (2023). Lessons learnt from 1300 consecutive gallbladder cancer surgeries: evolving role of perioperative chemotherapy in the treatment paradigm. Eur J Surg Oncol; 49: 107035.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.