Pelvic Hydatid Cyst in a Female Patient-Case Report and Literature Review

by Elis Ismail1*, Pavel Dobrev2, Emil Kovachev1, Simona Anzhel1

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical university-Varna, Bulgaria

2Department of Health care, Burgas state university, Bulgaria

Received Date: 06 January 2026

Accepted Date: 13 January 2026

Published Date: 15 January 2026

Citation: Ismail E, Dobrev P, Kovachev E, Anzhel S (2026) Pelvic Hydatid Cyst in a Female Patient-Case Report and Literature Review. J Surg 11:11539 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011539

Abstract

Introduction: Echinococcosis has been a significant problem in Bulgaria for many years, and efforts to control it have been underway since the 1960s, employing various measures with variable success [1].

Case presentation: We present a 23-year-old asymptomatic patient. During a routine gynecological examination, pelvic ultrasound identified a nonspecific tumor-like mass of solid consistency. The patient was referred for pelvic MRI, which demonstrated a primary hydatid cyst (cystic echinococcosis).

Discussion: The high prevalence of disease among children, adolescents, and young adults is indicative of ongoing transmission of the parasite and suggests that control measures directed at the source of infection remain inadequate. Studies from other countries likewise identify children and adolescents as the most heavily affected population group. In Bulgaria the peak incidence has been reported in individuals aged 10–19 years, while in Romania it occurs between 11 and 14 years. Children who have not acquired appropriate hygiene practices are more frequently infected through direct contact with infected dogs (e.g., petting or hugging). Indirect transmission occurs via ingestion of food or water contaminated with parasite eggs. The liver is the most common site of cyst localization, followed by the lungs. Involvement of the pelvic peritoneum is an atypical presentation and poses a diagnostic challenge. Between 2010 and 2019, 2,863 cases of human cystic echinococcosis were registered in Bulgaria, of which only three had a primary pelvic localization [2,3]. Imaging methods ultrasound, radiography, computerized tomography scan and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)] were used in patient. The diagnosis was confirmed by serological and histological methods.

Conclusion: Surgical management is the standard treatment. The pelvic location of cysts and involvement of the pelvic peritoneum, particularly in young females, may pose a risk to future reproductive potential. Surgical management should be as conservative as possible and avoid injury to the pelvic reproductive organs. For this reason, we emphasize the need to strengthen the National Echinococcosis Control Program to achieve a sustained reduction in incidence of Echinococcosis.

Keywords: Cystic Echinococcosis (Ce); Hydatid Cyst; MRI; Pelvic Tumor Mass; Ultrasonography

Introduction

Echinococcosis is cosmopolitan and widespread among domestic and wild animals and humans. The adult tapeworm inhabits the small intestine of dogs, foxes, wolves, jackals, coyotes, and other carnivorous mammals, while a wide range of animals - rodents and ungulates, both domestic and wild - and humans serve as intermediate hosts. Humans become infected by ingesting parasite eggs in contaminated food, water, or soil, or via direct contact with definitive hosts. More than 1 million people worldwide are affected by echinococcosis. The incidence of cystic echinococcosis in humans ranges from less than 1 per 100,000 to more than 200 per 100,000 in certain rural populations with close contact between domestic dogs and productive ungulates (most commonly sheep).

The incidence of human alveolar echinococcosis is generally lower (approximately 0.5 per 100,000) but may exceed 100 per 100,000 in specific communities (e.g., Tibetan herders). Bulgaria continues to rank among the European countries with the highest incidence of echinococcosis. As the most severe human helminth zoonosis, echinococcosis remains a major public health problem in many regions, with western China being the area of highest endemicity for both Cystic (CE) and Alveolar (AE) forms. Management is costly and complex, often requiring extensive and repeated surgical procedures and/or prolonged pharmacotherapy. Compared with other zoonoses, echinococcosis more frequently results in prolonged disability, recurrent disease, often permanent impairment, and high mortality, and it continues to have considerable medical, social, and economic impact nationally and globally [4-9]. Cystic Echinococcosis (CE), as a major zoonotic helminth infection, imposes remarkable socioeconomic burden on many endemic countries across the world, including Bulgaria. Due to the high importance of free-roaming dogs in the transmission of CE, epidemiological and molecular studies in this type of hosts are required in the endemic regions [3].

Case Presentation

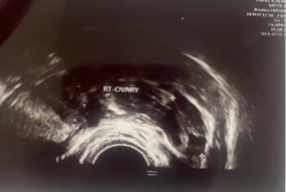

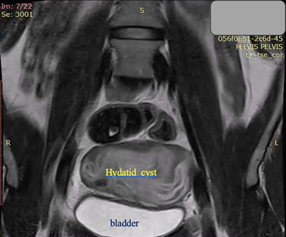

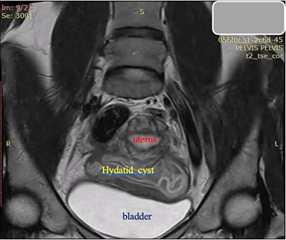

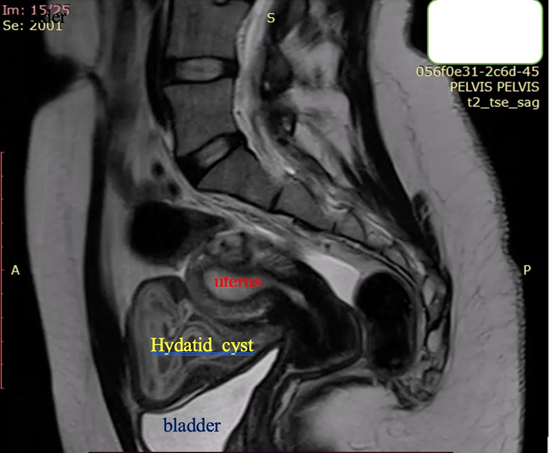

A 23-year-old asymptomatic female patient. During a routine gynecological examination, pelvic ultrasound identified a nonspecific tumor-like mass of solid consistency (Figures 1-3). The patient is sexually active and nulliparous. She has no history of abnormal menstrual bleeding or pelvic pain. Pelvic ultrasonography demonstrated a nonspecific tumor-like mass. The lesion was located in the vesicouterine space, anterior to the uterus (which was in anteversion and anteflexion with length 6.5 cm.) and posterior to the urinary bladder. The mass measured approximately 10 cm and had a predominantly solid component, with multilaminar hypoechoic bands within its capsule (Figures 1 and 4). Both ovaries were visualized and appeared normal on transvaginal ultrasonography (Figures 2 and 3). The pouch of Douglas is free of fluid.

Figure 1: Ultrasonographic image revealed a uterus of normal morphology, measuring 6.5 cm. in length.

Figure 2: TV-Ultrasonography image of left ovar-normal view.

Figure 3: TV-Ultrasonography image of right ovar-normal view.

Figure 4: Ultrasonographic image showing the uterus (outline in yellow) and an adjacent hydatid cyst (indicated by a red arrow).

Figure 5. Coronal T2-weighted MRI: The massive cystic formation displaces the bladder ventrally and alters the normal position of the uterus

Figure 7. Sagittal T2-weighted MRI: Bright hyperintensity, multiple cystic formation in the small pelvis, located retro-vesical and in contact with the uterus, with internal zones compatible with “daughter” cysts.

Subsequently, computed tomography of the upper abdomen identified a hepatic hydatud cyst. Chest radiography revealed no pathological findings. Laboratory investigations showed no evidence of active infection at the time of evaluation. Surgical management was undertaken, consisting of complete removal of the hydatid cysts from pelvis and liver. Intraoperatively, the lesions were found to represent old, calcified echinococcal cysts. One year later, in December 2025, the patient presented with a positive urine pregnancy test and ultrasonographic confirmation of an intrauterine spontaneous pregnancy at 6 weeks of gestation. Human echinococcosis results from ingestion of Echinococcus oncospheres, typically via contaminated environmental media. Recent evidence supports the view that transmission is predominantly soil- or environment-borne— analogous to classical soil-transmitted helminthiases—and most commonly occurs through a fecal–oral (hand-to-mouth) mechanism following contact with contaminated soil, vegetation or fomites. Food- or water-borne transmission (consumption of unwashed fruits and vegetables) and direct contact with infected definitive hosts (domestic dogs) also represent established routes, but may play a subsidiary role in many settings. In intermediate hosts, oncospheres penetrate the intestinal mucosa, enter the circulation and develop into hydatid cysts, with the liver and lungs being the most frequently involved organs in Echinococcus granulosus infection. Cysts may also localize in the pelvis and other anatomical sites. Hepatic involvement commonly manifests with right upper quadrant discomfort or a sense of mass effect.

Pulmonary cysts, the second most frequent localization, often enlarge more rapidly and may present with persistent, distressing cough, mucoid sputum that can be blood-streaked, and pleuritic chest pain when the pleura is affected. Pelvic or peritoneal locations may remain clinically silent for prolonged periods owing to the relative hypoesthesia of the peritoneum and the large potential spaces that permit expansion without early symptomatology. In intermediate hosts, diagnosis is frequently established post-mortem by identification of cysts, particularly in the liver and lungs; in livestock, cysts are often detected at meat inspection. In clinical practice, imaging modalities—principally ultrasonography, Computed Tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging— are used to detect cystic lesions; however, the specificity of imaging for definitive characterization of echinococcal cysts is limited and may be insufficient to establish etiology in isolation. Serological assays for anti-echinococcal antibodies or circulating antigens provide adjunctive diagnostic information but are subject to variable sensitivity and specificity depending on cyst location, stage and assay used; false-negative and false-positive results may occur. Histopathological examination of excised cyst material remains the reference standard for definitive diagnosis [5-8]. Management of cystic echinococcosis depends on cyst location, size, complications and host factors. Surgical resection remains the standard for large or symptomatic cysts. Percutaneous interventions such as PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection, re-aspiration) are an option for selected hepatic cysts under appropriate clinical protocols. Anthelmintic therapy (most commonly albendazole, with or without adjunctive agents) is used as primary therapy for inoperable disease, as an adjunct to surgery or percutaneous procedures, and for perioperative prophylaxis; treatment duration is individualized according to clinical guidelines and response to therapy. Multidisciplinary management involving infectious disease specialists and surgeons is recommended [9].

Discussion

Between 2002 and 2019 Bulgaria experienced a gradual decline in reported cases of echinococcosis, with annual case counts decreasing from 832 in 2002 to 193 in 2019. Over the same interval the average annual incidence fell from 8.2‰ in 2002 to 2.74‰ in 2019. Despite this downward trend, Bulgaria continues to rank among the countries with the highest incidence of echinococcosis in Europe and remains one of the most highly endemic member states of the European Union for Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. Investigations into the determinants of the sustained high burden indicate substantial deficiencies in population health literacy and health-related behaviours, which are compounded by a prolonged socio-economic crisis with adverse effects on population health indicators and overall quality of life. A particularly concerning finding is the disproportionate impact on younger age groups: the highest incidence was observed among children and adolescents aged 10–19 years (incidence 7.3‰). For the period 2000–2017 cases were reported in all regions of the country, with the greatest numbers of primary cases and recurrences recorded in Plovdiv (n = 963), Burgas (n = 655) and Sliven (n = 631) provinces. The mean incidence for 2002–2019 showed marked geographic heterogeneity, ranging from 1.6‰ in the city of Sofia to 15.8‰ in Sliven province. Molecular and epidemiological studies conducted in 2012 identified Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto as the predominant taxon in Bulgaria, comprising genotypes G1, G2 and G3 [3,10]. For a period 2010–2019, a total of 2863 cases of human Cystic Echinococcosis (CE) were registered in Bulgaria, of which 148 (5.17%) with organ localization other than liver and/ or lung. The majority of patients with extra-hepatopulmonary localization of CE were adults. The distribution by gender showed predominance of female patients (57.43%) over those of males and primary cases (85.14%) exceeded the cases of recurrence. According to our study most common is the spleen involvement, followed by involvement of the abdominal cavity, kidneys and muscle/subcutaneous tissue. Other extra-hepatopulmonary organ localizations are significantly less common. In 2020 a total of 488 confirmed human cases of echinococcosis were reported by 25 European Union Member States, of which 95 cases were reported in Bulgaria, corresponding to an incidence of 0.14 cases per 100,000 population [3]. This represents a decline of 16.2% relative to the 2019 incidence of 0.17 per 100,000 when data from the United Kingdom are included, and a decline of 28.4% relative to the 2019 incidence of 0.20 per 100,000 when United Kingdom data are excluded [1]. In the endemic countries, human CE poses a serious medical and social problem. Because it most often affects the liver and lungs we aimed to define the proportion of cases with different organ localization, the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in such cases, and the outcome of them [3]. In endemic regions, the incidence of cystic echinococcosis in humans may exceed 50 cases per 100,000 population, and prevalence levels of 5–10% have been reported in parts of Argentina, Peru, East Africa, Central Asia and China. Among slaughtered ruminants, the prevalence of cystic echinococcosis detected at abattoirs in hyperendemic areas of South America ranges from 20% to 95% of animals examined. The highest prevalence is observed in rural settings where older animals are more frequently slaughtered. The annual economic burden associated with cystic echinococcosis— comprising healthcare costs for case management and production losses in the livestock sector—is estimated at approximately USD 3 billion [4].

Conclusion

Cystic echinococcosis, principally caused by Echinococcus granulosus s.l., is among the most clinically significant parasitic diseases in Bulgaria. CE frequently results in prolonged morbidity and recurrent disease episodes, less commonly it leads to permanent disability and, in a minority of cases, to fatal outcomes. Clinically, CE behaves as a chronic parasitic disease characterized by the development of hydatid cysts most commonly within the liver, although cysts may develop in any organ and remain clinically silent for years. Progressive cyst enlargement produces mass effect with compression and functional impairment of the involved organ. Spontaneous or traumatic rupture of a hydatid cyst can precipitate severe systemic reactions, including life-threatening anaphylaxis. From an epidemiological perspective, Bulgaria remains a country with comparatively high CE incidence within Europe. Over the past three decades the Sliven region has reported the highest burden nationally. Of particular concern is the age distribution of cases: approximately 20% of reported infections occur in individuals aged 0–19 years, a pattern that is indicative of ongoing transmission and insufficient control of infection sources. The predominance of disease among children, adolescents and young adults indicates ongoing active transmission and suggests that control measures targeting infection sources are inadequate. Studies from other countries likewise identify children and adolescents as the population groups with the highest burden of infection. Prevention strategies should emphasize interruption of environmental contamination and transmission: promotion of hand hygiene after contact with soil or animals, thorough washing and, where appropriate, disinfection of raw fruits and vegetables, regular anthelmintic treatment and veterinary control of domestic dogs, avoidance of feeding dogs raw offal, and safe disposal of animal carcasses and viscera. Meat inspection programs and surveillance in livestock populations contribute to detection and control of infection reservoirs [1,3,4].

References

- Risk Assessment center on food chain. https://corhv.government.bg/ doi:10.5281/zenodo.7334530.

- Marinoiu A, Cobzaru C, Carcadea E, Capris C, Tanislav V, et al. (2013) Hydrogenolysis of glycerol to propylene glycol using heterogeneous catalysts in basic aqueous solutions. Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis 110: 63-73.

- Harizanov RN, Rainova IG, Kaftandjiev IT (2021) Extrahepatopulmonary cystic echinococcosis in Bulgaria: frequency, management and outcome of the disease. Parasitology 148: 562-565.

- World Health Organisation (2021) Echinococcosis. WHO News-Room Fact Sheets.

- Roming T etall (2015) Taxonomy and molecular epidemiology of Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. 2015, Veterinary Parasitology 213: 76-84.

- OIE, Echinococcosis.

- Breyer I, Georgieva D, Kurdova R, Gottstein B (2004) Echinococcus granulosus strain typing in Bulgaria: the G1 genotype is predominant in intermediate and definitive wild hosts. Parasitol 93: 127-130.

- European Food Safety Authority / European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2021) The European Union One Health 2020 Zoonoses Report

- Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA,Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE (2010) Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 114: 1-16.

- Casulli A, Interisano M, Sreter T, Chitimia L, Kirkova Z, et al. (2012) Genetic variability of Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto in Europe inferred by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Infect Genet Evol 12: 377- 383.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.