Paget’s Disease of Bone and Chronic Kidney Disease: Three Case Reports

by Lorena Traversari*

U.O.S.D. Nefrologia e Dialisi Ospedale Massa Marittima, Italy

*Corresponding Author: Lorena Traversari, U.O.S.D. Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale di Massa Marittima, Azienda USL Toscana Sud Est, Italy

Received Date: 19 December 2025

Accepted Date: 26 December 2025

Published Date: 29 December 2025

Citation: Traversari L. (2025). Paget’s Disease of Bone and Chronic Kidney Disease: Three Case Reports. Ann Case Report. 10: 2496. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-7754.102496

Abstract

Paget’s Disease of Bone (PDB), first described in 1877, remains a clinical condition of unknown etiology, despite being the second most common bone disease after osteoporosis. In contrast with diffusion of PDB and chronic kidney disease (CKD), few cases of patients affected by the two diseases concurrently have been reported. The presence of CKD requires special attention and customization in the use of drugs and in maintaining normal blood calcium values, as well as the presence of PDB should influence decisions regarding eligibility of a kidney transplant recipient. This paper describes three cases of patients with coexistence of the two diseases, followed over the same period in our department.

Keywords: Paget’s Disease of Bone; Chronic Kidney Disease; Survival; Mortality; Kidney Transplantation.

Introduction

PDB is a chronic disease of unknown etiology with variable distribution and prevalence worldwide. It originated in Europe and then spread through emigration, today it has the highest prevalence in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, followed by the United States and Canada, while it is uncommon in Asia [1]. In Italy, the prevalence of the disease is at least 1% of the population, with regional variations and unlike high-prevalence countries (e.g., UK, Australia, and New Zealand), Italy has seen no reduction in PDB prevalence and severity over recent decades [2]. Males over 50 and some ethnic groups are more affected, and familial cases are linked to genetic mutations [3,4,5]. The alterations can affect a single bone (monostotic forms) or affect multiple bones in an asymmetrical way (polyostotic forms). PDB is asymptomatic in the majority of cases; only 10% of patients complain of pain and seek medical attention. Other symptoms depend on the affected bone segments, nerve compression, and joint involvement [6]. The frequency of vertebral and long bone fractures is high and is due to bone remodeling characterized by hyperactivity of osteoclasts with excessive deposition of abnormal bone matrix by osteoblasts, which causes bone deformation and weakness [7].

Recent studies indicate an increased cardiovascular risk in patients with PDB, whose extraosseous complications include vascular and valvular calcifications [8], as well as increased morbidity and mortality compared to healthy subjects [3]. Higher fasting glucose levels and elevated systolic blood pressure are also observed in patients with PDB compared to controls [9]. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension are known risk factors for CKD, and vascular and valvular calcifications are common complications of CKD, as are increased morbidity and mortality compared to healthy subjects [10,11].

Although the two pathologies share several characteristics such as chronicity, high cardiovascular risk and diffusion in the population over 50, there are few descriptions of clinical cases in which patients are affected by the two diseases.

Case Presentation

The few cases of PDB coexisting with CKD published to date are summarized in Table 1.

|

Autor |

year |

n° cases |

Gender/ age |

CKD/HD/PD |

monostotic / polyostotic form |

SHTP/other bone disease |

Treatment of SHPT/ parathyroidectomy |

Syntomatic/asyntomatic |

Treatment of PDB |

|

J.D. Ringer |

1985 |

1 |

f/48 |

HD |

SHTP+ alluminium- induced osteomalacia |

parathyroidectomy |

bone pain |

||

|

R. Lorho |

1998 |

1 |

m/83 |

HD |

M/pelvis |

SHTP |

alphacalcidiol and parathyroidectomy |

undocumented |

undocumented |

|

J. Etemadi |

2008 |

1 |

f/77 |

HD |

M/skull |

no |

no |

bone pain |

alendronate |

|

L. Wu |

2009 |

1 |

f/77 |

PD |

M/lumbar spine |

undocumented |

undocumented |

radicular syndrome |

calcitonin |

|

G. Cianciolo |

2010 |

1 |

f/69 |

HD |

M/skull |

SHTP |

sevelamer, cinacalcet, paricalcitol |

clodronate |

|

|

E. De Sousa Amorim |

2012 |

1 |

m/72 |

PD |

P/ right iliac bone, cervical spine, left ulna, external malleolus of left ankle |

SHTP |

cinacalcet, calcifediol |

asyntomatic |

no |

|

E.J. Raubenheimer |

2015 |

1 |

f/30 |

HD for two years and PD for 9 years |

M/palate |

undocumented |

undocumented |

undocumented |

undocumented |

|

E.J. Raubenheimer |

2015 |

1 |

f/31 |

PD 13 years |

M/mandible |

undocumented |

undocumented |

undocumented |

undocumented |

|

R. P. Kenneth |

2016 |

1 |

m/68 |

HD (PDB was diagnosed 14-15 years before the start of dialysis) |

P/pelvis, thoracic spine, right humerus, skull |

SHTP |

Paracalcitolo, calcium acetate, Lanthanum carbonate, ergocalciferol/calcitiol |

undocumented |

no |

|

PK. Chan |

2019 |

1 |

m/80 |

CKD (stage V) |

M/pelvic bone |

SHTP |

undocumented |

asyntomatic |

no |

|

N. Kuthiah |

2018 |

1 |

f/63 |

CKD (cl.c 23 mil/ min) |

P/left iliac and pubic bone, left tibia |

undocumented |

undocumented |

syntomatic |

denosumab |

|

V.A. Panuccio |

2020 |

1 |

m/60 |

CKD (PD was started 3 years later) |

P/long bones, skull |

SHTP |

Calcium-based phosphate binder, active Vit. D, |

bone pain |

Clodronate, calcitonin |

|

Abbreviations: PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; CKD, chronic kidney disease; SHPT, secondary hyperparathyroidism; PDB, Paget’s disease of Bone. |

|||||||||

Table 1: Cases of PDB on CKD described in the literature. Taken from E. de Sousa-Amorim, G. del Peso-Gilsanz, M. Auxiliadora BajoRubio et al. Asymptomatic polyostotic Paget’s disease associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism in a patient on peritoneal dialysis, Nefrologia 2012;32(4):542-4, updated and completed by L. Traversari

The following three cases demonstrate the concurrent presence of PDB and CKD, all managed within our department. Two of these cases were diagnosed within a two-year span, underscoring the prevalence of PDB in CKD patients. The management of these cases required special choices, particularly concerning pharmacological treatment and long-term follow-up.

First Case: A 75-year-old Caucasian male from Calabria, a southern region of Italy, was referred to our clinic after relocating from an inland city to the seaside. He had already been diagnosed with CKD G5 but had not yet started renal replacement therapy. Diagnosed with Paget’s disease at age 33, he had a long history of recurrent bilateral kidney stones. His medical history was negative for hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dyslipidemia.

In 2015, his creatinine level was 3 mg/dL, and he had begun a low-protein diet. In 2019, he suffered fractures in both femurs, beginning with the left femur, followed by the right femur two months later. Additionally, he experienced a traumatic Achilles tendon rupture in 1979.

Over time, the patient’s height decreased by more than 40 cm, and his joint mobility progressively worsened. He reported undergoing all available PDB therapies, including bisphosphonates (clodronate, alendronate, zoledronic acid, etidronate, pamidronate), calcitonin, and vitamin D for decades. In 2010, he achieved good control of bone metabolism with ALP normalization, coinciding with the onset of CKD (creatinine at 1.7 mg/dL).

In 2014, he developed osteonecrosis of the jaw, managed with amoxicillin and metronidazole. A denosumab cycle was recommended following his femur fractures. Baseline sequential renal scintigraphy on August 3, 2012, showed a GFR of 32 ml/min, mainly supported by the right kidney (23 ml/min), with normal vascular phase and cortico-medullary transit of the DTPA-TC99M indicator, without signs of obstruction.

In May 2019, his lab results showed Hb 10.8 g/dL (normal 1418), creatinine 3.26 mg/dL (normal 0.67-1.17), and calcium 10.4 mg/dL (8.6-10.2), and PTH 2.7 pg/mL (6.5-36.8). His condition worsened in October 2020 (Hb 9.8 g/dL, creatinine 4.39 mg/dL, calcium 10.7 mg/dL) and January 2021 (Hb 9.8 g/dL, creatinine 4.92 mg/dL).

Upon initial admission to our department (January 2021), the patient was wheelchair-bound due to severe deformities typical of polyostotic PDB, with involvement in the skull, pelvis, long bones, spine, sternum, clavicles, scapulae, rib arches, and the left humeral head.

Physical examination revealed blood pressure 120/75 mmHg, heart rate 90 bpm, and body weight 74.5 kg. Lab results were as listed in (Table 2) with an eGFR of 11ml/min/1.73 m². Urine analysis showed proteinuria (10 mg/dL) and leukocyturia (31/field), though no symptoms of infection were reported. The patient’s home therapy included allopurinol 300 mg/day, iron sulfate 105 mg/day, folic acid 5 mg/day, ramipril 2.5 mg/day, calcitriol 0.5 mcg/day, and paracetamol as needed.

|

Items |

Patient’s data |

Normal value |

|

Hb |

9.8 g/dL |

14-18 g/dL |

|

creatinine |

4.39 mg/dL |

0.67-1.17 mg/dL |

|

urea |

urea 86 mg/dL |

13-49 mg/dL |

|

calcium |

10.8 mg/L |

8.6-10.2 mg/dL |

|

phosphorus |

5.05 mg/dL |

2.5-4.5 mg/dL |

|

magnesium |

1.98 mg/dL |

1.5-2.6 mg/dL |

|

sodium |

135 mg/dL |

136-145 mEq/L |

|

uric acid |

4.9 mg/dL |

3.4-7.0 mg/dL |

|

total protein |

6.11 g/dl |

6.0-8.0 mg/dL |

|

albumin |

4.6 g/dL |

3.5-5.2 g/dL |

|

iron |

57 ug/dL |

33-193 ug/dl |

|

Ferritin |

224 ng/mL |

30-400 ng/mL |

|

PTH |

6.0 pg/mL |

6.5-36.8 pg/mL |

|

bicarbonate |

14.5 mmol/L |

23-28 mmol/L |

|

ionized calcium |

1.39 mmol/L |

1.16-1.29 mmol/L |

|

25-OH vitamin D3 |

18 ng/mL |

30-100 ng/mL |

|

1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3 |

49.4 pg/mL |

19.9-79.3 pg/mL |

Table 2: Laboratory data Case 1

The patient reported hypotension and elevated calcium levels over the previous 20 days, leading to his discontinuation of ramipril and reduction of calcitriol to 0.5 mcg every other day. We initially stabilized his blood pressure, corrected anemia with epoetin alfa (2000 UI 3x/week), and controlled hypercalcemia per KDIGO guidelines, which advise avoiding hypercalcemia in CKD G3aG5D patients [12]. Calcemia was managed by discontinuing calcitriol and introducing cinacalcet (off-label).

During follow-up, his clinical condition initially declined, then improved gradually, with eGFR stabilizing around 20-21 ml/ min. Hyperphosphatemia was managed within three months, maintaining phosphorus around 4 mg/dL. Following calcium normalization, ALP and PTH levels rose, necessitating increased cinacalcet and initiating paricalcitol to maintain normocalcemia. PTH peaked at 70.6 pg/mL and ALP at 449 IU/L (normal 40-129) with BALP at 108 ng/L (normal 5.5-24.6). Although the optimal PTH range for CKD G3-G5 without dialysis is unclear [12], we aimed to keep PTH slightly above twice the upper limit of normal to avoid adinamic bone disease in healthy bone.

Discussion

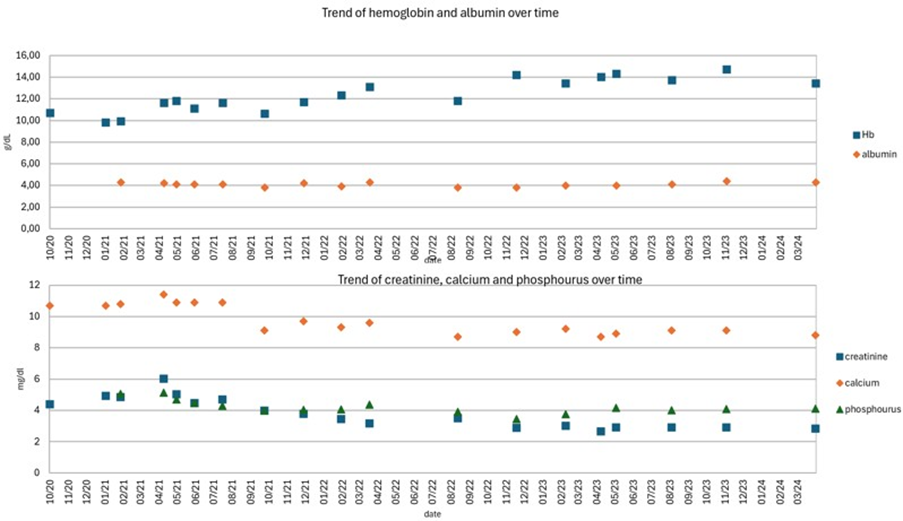

This case of CKD secondary to clinical and therapeutic complications of a severe form of PDB highlights the role of personalized therapy in stabilizing the progression of CKD through the control of blood pressure, anemia and especially hypercalcemia (Figure 1). In addition, eucalcemia eliminated the new formation of kidney stones with interruption of renal colic and stones emission. PDB is a risk factor for nephrolithiasis (NL), the most common renal disorder associated with this disease, regardless of disease activity. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, and hyperuricemia are potential metabolic complications of PDB that can lead to the formation of kidney stones [13].

Figure 1: Case 1: trend of hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, calcium and phosphorus over time. Blood tests show how, in conditions of nutritional stability (Hb, albumin, phosphorus), prolonged eucalcemia led to a progressive reduction in creatinine values.

In severe forms of PDB, drugs can also play an important role in the development of CKD. Bisphosphonates, the first-line drugs for the treatment of PDB, are the only drugs evaluated in scientific studies to date [14,15]. Other commonly used drugs, such as analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), lack scientific evidence. Bisphosphonates effectively reduce bone turnover, but, especially when used intravenously, have shown potential nephrotoxicity due to glomerular and tubular damage, leading to acute renal failure. Therefore, they are generally contraindicated when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls below 35-30 ml/ min/1.73 m² [16]. Bisphosphonates cause hypocalcemia and induce prolonged use of calcium and vitamin D supplements, which may contribute to soft tissue calcification and kidney stone formation. NSAIDs can accelerate the decline in GFR, worsen fluid overload and electrolyte imbalance, and exacerbate coexisting hypertension and heart failure [17]. GFR can be further reduced by the combined action of NSAID diuretics and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors by influencing glomerular hemodynamics [18]. Therefore, they are not recommended in patients with CKD.

Regarding hormonal alterations in our patient, despite therapy with cinacalcet, PTH increased. Cinacalcet, a calcium mimetic agent, has the ability to reduce PTH both in conditions of normal total calcium values or hypocalcemia as in secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) and in conditions of hypercalcemia as in primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) [19]. The increase in PTH suggests that prolonged normocalcemia can stimulate PTH secretion through the modulation of CaSR [20].

The patient’s quality of life improved marked itching subsided, muscle strength increased, and he regained the ability to exercise, swim, and perform daily activities independently. Correction of serum calcium levels also contributed to the improvement in muscle symptoms. Hypercalcemia, by increasing the depolarization thresholds of cell membranes, causes varying degrees of muscle weakness [21].

However, he opted to delay further imaging (bone scintigraphy), satisfied with clinical improvements and stable biochemical markers. In any case, the good results obtained do not allow us to know whether changes in the Pagetic bone occurred and whether the typical alterations in bone metabolism of CKD may have influenced them.

Second Case: A 53-year-old male from North Macedonia with pre-existing CKD presented to the emergency department in end-stage renal disease (ESRD), requiring renal replacement therapy. The patient, who spoke limited Italian, reported a history of hypertension, renal colic episodes, and nephrolithiasis, as recounted by family members.

Some initial blood tests are evinced in (Table 3). Liver function tests, iron, ferritin, coagulation parameters, and autoimmune markers were unremarkable.

|

Items |

Patient’s data |

Normal value |

|

Hb |

8,4g/dL |

14-18 g/dL |

|

creatinine |

7.59 mg/dL |

0.67-1.17 mg/dL |

|

urea |

79 mg/dL |

13-49 mg/dL |

|

calcium |

8.2 mg/L |

8.6-10.2 mg/dL |

|

phosphorus |

4.77 mg/dL |

2.5-4.5 mg/dL |

|

sodium |

138 mg/dL |

136-145 mEq/L |

|

uric acid |

6 mg/dL |

3.4-7.0 mg/dL |

|

total protein |

5 g/dl |

6.0-8.0 mg/dL |

|

albumin |

2.8 g/dL |

3.5-5.2 g/dL |

|

iron |

57 ug/dL |

33-193 ug/dl |

|

Ferritin |

224 ng/mL |

30-400 ng/mL |

|

PTH |

216 pg/mL |

6.5-36.8 pg/mL |

|

ALP |

287 IU/L |

40-129 IU/L |

|

bicarbonate |

14.5 mmol/L |

23-28 mmol/L |

|

CRP |

1,28 mg/dL |

<0.5 mg/dL |

|

Glucose |

90 mg/dL |

74-109 mg/dL |

|

glycated Hb |

4.50% |

<6% |

Table 3: Laboratory data Case 2.

Urinalysis indicated proteinuria (300 mg/dL) and microhematuria, with a 24-hour albuminuria of 5.6 g. He showed no symptoms of a urinary tract infection. Physical examination was normal except for elevated blood pressure at 198/103 mmHg. An abdominal ultrasound confirmed chronic nephropathy with bilateral renal cysts, with no signs of urinary obstruction.

A central venous catheter was placed in the right internal jugular vein to initiate dialysis, and an arteriovenous fistula was scheduled. Following stabilization, the patient was transferred to our department to continue thrice-weekly dialysis.

At discharge, he was prescribed amlodipine 10 mg/day, transdermal clonidine 5 mg/week for hypertension, along with furosemide 250 mg on non-dialysis days, calcitriol 0.25 mcg/day, simvastatin 20 mg, calcium carbonate 1000 mg twice daily, and pantoprazole 20 mg/day. He also received erythropoietin alfa (10,000 IU) after each dialysis session.

Over the following months, the patient responded well to erythropoietin, and both PTH and ALP levels progressively decreased to near-normal values (PTH 43.6 pg/mL, ALP 70 IU/L), likely due to SHPT improvement.

During his pre-transplant evaluation, a pelvic X-ray revealed PDBspecific changes in the left iliac bone, showing bone enlargement. Total-body bone scintigraphy demonstrated intense radionuclide fixation in the D4, D5, D8, and L4 vertebrae, moderate-to-intense uptake in the left iliac wing (notably around the acetabulum and iliopubic branch), and intense uptake in the left femoral head, alongside mild uptake in the upper half of the left femur. Hyperfixation was also seen near the iliopubic and ischiopubic branches on the right, adjacent to the acetabulum. These findings were consistent with active polyostotic PDB. A CT scan of the dorsal spine and pelvis identified structural changes in the D5, D6, D9, and L4 vertebrae, iliac bones, and left femoral epiphysis, along with biconcave deformities in the D6, D9, and D4 vertebrae.

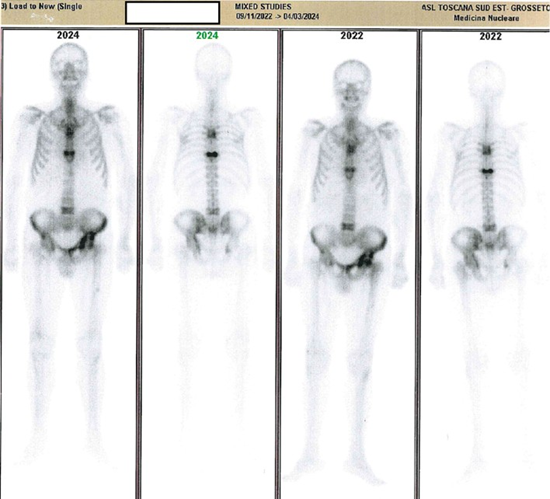

Despite having multiple polyostotic lesions, including vertebral and femoral involvement, the patient was asymptomatic and led a relatively active lifestyle. Following guideline recommendations for asymptomatic forms of PDB, we opted against bisphosphonate therapy. We scheduled PTH, ALP, and BALP monitoring and a follow-up bone scintigraphy after two years, which showed no disease progression (Figure 2). Consequently, the initial decision to forego treatment remained appropriate.

Figure 2: Case 2: comparative scintigraphy reports.

Discussion

This case illustrates the incidental diagnosis of PDB in a CKD patient with SPTH. Asymptomatic patients often reach a PDB diagnosis only through routine or incidental imaging. Given that bisphosphonates are not indicated for dialysis patients, and treatment is not typically advised for asymptomatic cases, the patient continued without specific PDB treatment [14,16]. The normalization of ALP and absence of pain further supported the decision to monitor without intervention. Furthermore, bisphosphonates have not demonstrated efficacy in preventing fractures, therefore in our patient, who presented with vertebral deformations, even the hypothesis of preventive use was unacceptable [14].

The case also raises an important question regarding renal transplantation due to the coexisting presence of PDB, a chronic disease of unknown etiology that, in symptomatic acute phases, requires the use of nephrotoxic drugs such as bisphosphonates and NSAIDs to reduce Paget’s bone remodeling and control pain [14].

Rejection and action of immunosuppressive drugs are usually the cause of progressive renal damage in transplanted kidneys [22]. In patients with coexisting PDB, renal damage may be worsened by the toxicity of bisphosphonates and painkillers required for any flare-ups.

Third Case: A 79-year-old Italian male from Grosseto first presented to our department in 2010 with CKD and proteinuria. His medical history included hypertension and benign prostatic hypertrophy. Physical examination findings were unremarkable. Blood tests revealed creatinine at 2 mg/dL (normal 0.67-1.17), urea at 104 mg/dL (normal 13-49), uric acid at 10.4 mg/dL (normal 3.4-7.0 ), calcium at 9.4 mg/dL (normal 8.6-10.2), PTH at 86 pg/mL (normal 6.5-36.8), and ALP at 107 IU/L (normal 40129). Total urine protein was 1.14 g/dL. Tests for autoantibodies, complement levels, viral markers (HBV, HCV, and HIV), urinary light chains, serum protein electrophoresis, ESR, and CRP were all within normal limits.

His home medications included sartans for blood pressure control, allopurinol for hyperuricemia, and calcitriol for SHPT. Ultrasound revealed bilaterally shrunken kidneys with reduced parenchymal thickness and increased echogenicity. Due to the advanced state of CKD, renal biopsy was not pursued.

Over subsequent years, the patient developed multiple primary malignancies. In 2015, he underwent a hemicolectomy for a high-grade tubulovillous adenoma. In 2018, he required bilateral nephrectomy for multiple nodules of clear cell carcinoma, and in 2019, he underwent left lobectomy for squamous cell carcinoma. In 2017, he also started thrice-weekly hemodialysis.

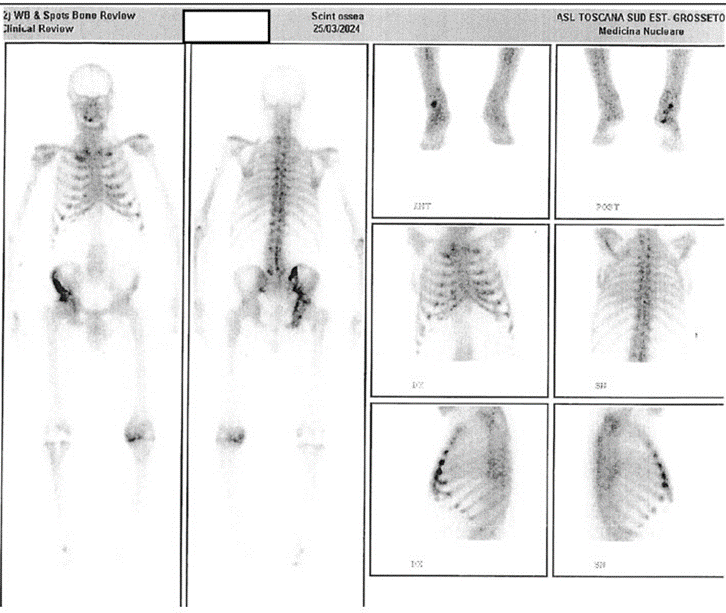

During oncological follow-up, abdominal CT (2018) and wholebody CT scans (2019-2021) showed no bone lesions. However, in January 2022, a CT scan revealed a lesion in the right iliac bone, typical of PDB, which was stable on follow-up scans in December 2022 and January 2024. To assess disease extent, a total-body bone scintigraphy was performed in March 2024, showing a large, irregular area of bone remodeling in the right hemipelvis, involving the acetabular cavity and potentially the femoral head. Additional findings included increased uptake in the anterior rib ends, suggesting either chondrocostal calcifications or PDB involvement in the chest (Figure 3).

Throughout these years, PTH levels remained controlled with calcitriol, later replaced by paricalcitol (1 mcg/day). However, due to supply issues, paricalcitol was interrupted, causing PTH levels to gradually increase, though they remained within the guidelinerecommended range (2-9 times the upper limit for dialysis patients) [14]. ALP, which was previously stable, began to fluctuate between upper-normal and slightly elevated values, peaking at 146-183 IU/L (normal 40-129) with normal liver function. As PTH and ALP levels rose, BALP levels also increased, reaching 47.8 ug/L (normal 5.5-24.6).

Ultrasound revealed a 5 mm oval formation near the lower parathyroid glands, suggesting parathyroid adenoma. Intravenous calcimimetic therapy with etelcalcetide (5 mg, three times weekly) was initiated, gradually reducing PTH and normalizing ALP and BALP.

Discussion

Despite the asymptomatic polyostotic nature of his PDB, no specific treatment was provided, consistent with guidelines advising against therapy for asymptomatic forms of PDB [14] and for dialysis patients [16]. The observed rise in bone turnover markers was attributed to SHPT, effectively managed with etelcalcetide, normalizing PTH, ALP, and BALP.

This case underscores the incidental diagnosis of PDB in a dialysis patient during oncologic follow-up. The late diagnosis of PDB in this case may be due to both the slow development and radiological manifestation of the bone lesions, as well as their nonspecificity. The imaging features typical of PDB are multiple and relate to the different phases of bone remodeling. Lytic and sclerotic areas, trabecular and cortical thickening, bone deformity and expansion are lesions that alone are not specific for PDB, but when combined, they provide characteristic X-ray features of the disease [23]. The experience of the radiologist who interprets the X-ray images and who can first suggest the diagnostic hypothesis is also important. There is therefore the necessity of vigilance for PDB throughout the lifetime of a CKD patient, as typical bone lesions may not immediately present in imaging and may emerge after several years.

Conclusions

Patients with CKD and metabolic bone disease, elevated PTH and ALP blood levels, may be a population in which it is useful to look for signs of PDB. Management of patients with PDB and CKD is complicated by the need to take into account drug nephrotoxicity and personalization of care is essential. During screening of renal transplant recipients, coexisting PDB should be assessed as an increased risk of worsening renal function before providing eligibility.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Financial Support: Many thanks to the Nefro Toscana Onlus association for paying the publication costs.

Acknowledgments: We thank the patients who permitted the sharing and publication of their clinical experiences. Special thanks to Alessio Mencaroni for linguistic revision.

References

- Mays S. (2010) Archeological skeletons support a northwest European origin for Paget’s disease of bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 25: 1839-1841.

- Gennari L, Di Stefano M, Merlotti D, Giordano N, Martini G, et al. (2005) Prevalence of Paget’s disease of bone in Italy. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 20: 1845-1850.

- Van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, Lyles K, Sprafka JM, et al. (2002) Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 17: 465-471.

- Corral-Gudino L, Borao-Cengotita-Bengoa M, Del Pino-Montes J, Ralston S. (2013) Epidemiology of Paget’s disease of bone: a systematic review and meta-analysis of secular changes. Bone. 55: 347-352.

- Gennari L, Rendina D, Merlotti D, Cavati G, Mingiano C, et al. (2022) Update on the pathogenesis and genetics of Paget’s disease of bone. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 10: 1-15.

- Siris E, Roodman GD. (2008) Paget’s disease of bone. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 7: 335-343.

- Siris ES. (1998) Paget’s disease of bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 13: 1061-1065.

- Merlotti D, Gennari L, Galli B, Nuti R. (2005) Paget’s disease of bone: clinical features and management. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 20: 1356-1364.

- Barale M, Cappiello V, Ghigo E, Procopio M. (2019) Increased frequency of impaired fasting glucose and isolated systolic hypertension in Paget’s disease of bone. Endocrine. 63: 385-390.

- Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. (2013) Management of progression and complications of chronic kidney disease. Kidney International Supplements. 3: 73-90.

- Shanahan CM, Crouthamel MH, Kapustin A, Giachelli CM. (2011) Arterial calcification in chronic kidney disease: key roles for calcium and phosphate. Circulation Research. 109: 697-711.

- KDIGO. (2009) Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, development, prevention, and treatment of CKD-MBD. Kidney International Supplements. 76: 1-130.

- Rendina D, De Filippo G, Merlotti D, Stefano MD, Mingiano C. (2020) Increased prevalence of nephrolithiasis and hyperoxaluria in Paget’s disease of bone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 105: 4430-4438.

- Ralston SH, Corral-Gudino L, Cooper C, Francis RM, Fraser WD. (2019) Diagnosis and management of Paget’s disease of bone in adults: a clinical guideline. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 34: 579-604.

- Corral-Gudino L, Tan AJ, Del Pino-Montes J, Ralston SH. (2017) Bisphosphonates for Paget’s disease of bone in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: 1-25.

- Miller PD. (2011) The kidney and bisphosphonates. Bone. 49: 77-81.

- Baker M, Perazella MA. (2020) NSAIDs in chronic kidney disease: are they safe? American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 76: 546-557.

- Camin RMG, Cols M, Chevarria JL, Osuna RG, Carreras M. (2015) Acute kidney injury secondary to a combination of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, diuretics and NSAIDs: the triple whammy. Nefrologia. 35: 197-206.

- AIFA. (2020) Italian Medicines Agency. AIFA Publications. 1: 1-10.

- Jiang YF, Zhang Z, Kifor O, Lane CR, Quinn SJ, et al. (2002) Protein kinase C phosphorylation of the calcium-sensing receptor modulates functional interaction of G proteins with the receptor cytoplasmatic tail. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277: 50543-50549.

- Crowley R, Gittoes N. (2013) How to approach hypercalcaemia. Clinical Medicine. 13: 287-290.

- Icardi A, Sacco P, Salvatore F. (2008) Long-term care of the kidney transplant patient. Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia. 25: 325-341.

- Theodorous DJ, Theodorous SJ, Kakitsubata Y. (2011) Imaging of Paget’s disease of bone and its musculoskeletal complications. American Journal of Roentgenology. 196: 64-75.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.