Open Surgical Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm with Horseshoe Kidney with Renal Perfusion Solution

by Francesco Natale Guarnaccia1*, Nunzio Montelione2, Francesco Alberto Codispoti2, Giovanni Tinelli1, Tommaso Donati1, Francesco Stilo2**, Francesco Spinelli2 ***, Yamume Tshomba1

1Vascular Surgery Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Roma, Italy

2Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Fondazione Campus Bio-Medico, Rome, Italy

*Corresponding author: Francesco Natale Guarnaccia, Vascular Surgery Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Agostino Gemelli, Rome, (CAP:00168), Italy

**Chief of research unit.

*** Chief of clinical unit.

Received Date: 01 October 2024

Accepted Date: 07 October 2024

Published Date: 09 October 2024

Citation: Guarnaccia FN, Montelione N, Codispoti FA, Tinelli G, Donati T, et al. (2024) Open Surgical Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm with Horseshoe Kidney with Renal Perfusion Solution. J Surg 9: 11155 https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.11155

Abstract

Introduction: Horseshoe Kidney (HSK) is an uncommon urologic anomaly, with a prevalence of 0.25%. When an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) coexists with HSK, the management becomes complex as the frequent variation of renal arteries complicates surgery. In this article, we present six cases of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm coexisting with HSK who underwent open aortic surgery with Custudiol perfusion of renal arteries.

Methods: Prospective, double-center study included patients submitted to AAA open repair with horseshoe kidney between 2018 and 2022. Indications for surgery were AAA > 55 mm or rapid growth >1cm/year. Preoperative risk factors, aneurysm features, intraoperative details, postoperative outcomes, and follow-up data were collected.

Results: During the study period, 850 patients were treated with AAA. Among them, 7 patients (0,8 %) with associated HSK were included. In 5 patients a median laparotomy was performed and in 1 patient a retroperitoneal approach was chosen. Mean age was 72.3. Mean intensive care unit length of stay was 1.3 days with a mean hospital length of stay of 5 days. There was no change of renal function, neither 30-days death nor major complications reported. On average, a 24 months follow-up did not require other interventions, and renal functions remained well preserved in all patients.

Conclusion: Open Surgical Repair of AAA with HSK is a feasible, effective, and safe technique at experienced centers. Custudiol perfusion of renal arteries in all cases can help to preserve renal function.

Keywords: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; Custudiol; Horseshoe Kidney; Open Surgical Repair; Renal Artery

Abbreviations: AAA: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; HSK: Horseshoe Kidney

Introduction

Horseshoe Kidney (HSK) is an uncommon urologic anomaly, with a prevalence of 0.25% [1]. A medial fusion of the kidneys anterior to the aorta is the main characteristic of this anomaly. When an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) coexists with HSK, the surgical management becomes complex because of the variation of renal arteries, the type of abdominal exposure and the ligation or salvage of accessory renal arteries [2]. Several studies show the endovascular feasibility in selected cases [3]. Owing to the limited state of knowledge, no firm recommendations can be made. We present our experience in the treatment of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm coexisting with HSK who underwent open aortic surgery with cold renal perfusion using Custudiol to prevent kidney injury.

Methods

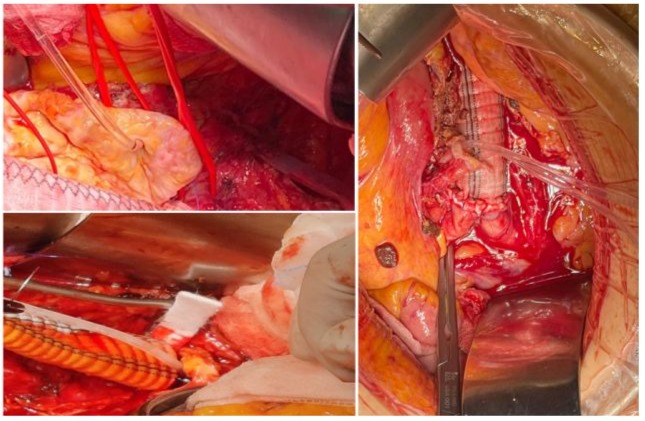

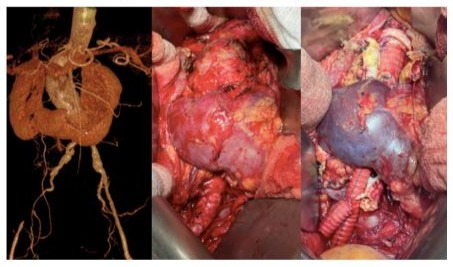

A prospectively study that included patients submitted to elective AAA open repair with horseshoe kidney was performedbetween 2018 and 2023 in two high volume centers. During the study period, 850 patients undergoing open AAA surgical repair. Among them, 7 patients (0,8%) had concomitant HSK. Indications for surgery were AAA > 55 mm or rapid growth >1cm/year. All patients were submitted to preoperative CTA to assess renal arteries anatomy and surgical revascularization strategy. Surgical approach was median laparotomy or retroperitoneal. To prevent kidney injury, the renal arteries were perfused with a histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) solution (Custodiol; Dr. Franz-Kohler Chemie GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) using Pruitt-Inhara shunt or Perfusion catheter (Figure 1). After rapid intra-arterial administration of a bolus of 100 mL for each one, Custodiol was given at a perfusion pressure allowing administration of 10-20 ml/min up to 800 ml of maximum infusion volume. Operative time, blood loss, mean intensive care unit length and mean hospital length was recorded. Renal function was estimated with the serum creatinine and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. We evaluated in the postoperative time the renal function and the acute kidney injury (AKI) according to the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) including acute alterations in serum creatinine or urine output [4].The follow up protocol included physical examination, complete blood count, renal panel and doppler US at 30-day. Doppler ultrasound was then performed at 6 months, at 1 year, and yearly thereafter. All patients underwent CTA 1 year after the index procedure. Outcome measures were 30-day, 1-year, and mean follow-up all-cause mortality, major complications rates including pulmonary, major adverse cardiac events (MACE), and renal function variation.

Figure 1: Renal Perfusion with Custudiol.

Results

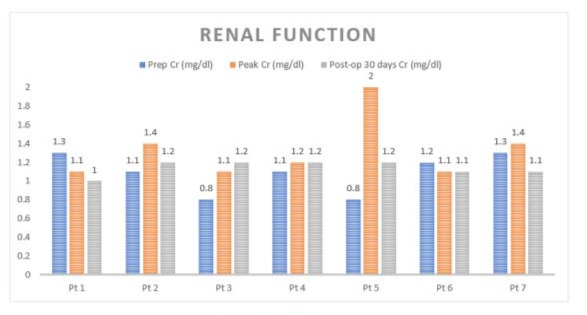

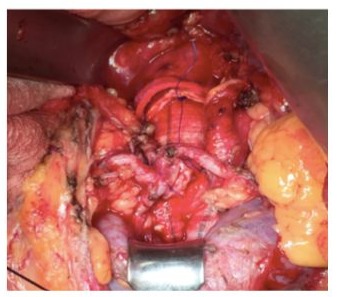

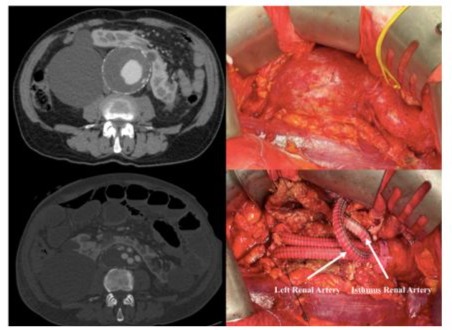

The study group consisted of 6 men and 1 female with a mean age of 69.6 (range 65-75). Preoperative patient’s risk factors and comorbidities were reported in Table 1. Mean aneurysm size was 6,2 cm (range 5,5-7,0 cm). Preoperative renal function was normal in all patients with a mean serum creatinine of 1,05 mg/ dl (range 0,8-1,3 mg/dl) and eGFR > 90 ml/min/1.73 m2 (range 88-94 ml/min/1.73 m2). In 6 (85 %) cases, a median laparotomy was performed and in 1 (14 %) case a retroperitoneal approach was preferred. Aorto-aortic graft interposition was performed in 5 cases (71 %), while in the remaining 2 (28 %) a bifurcated aortoiliac graft was executed. In one of the bifurcated grafts, a jump from the right prosthetic branch to right common femoral artery was necessary due to a preoperative occlusion of external iliac artery (Figure 4). The accessory renal arteries were replanted on the prosthesis in a single aortic patch in 6 (85 %) cases (Figure 2) and in 1 case, by the retroperitoneal approach, a bypass for the isthmus renal arteries and the principal left renal artery were performed (Figure 3). In 1 case we perfomed a longitudinal dissection of renal isthmus. Mean intensive care unit length of stay was 1.5 days (range 1-2 days) with a mean hospital length of stay of 5 days (range 4-8 days). In 6 (85 %) cases there was no change of renal functions, only in 1 (14%) patient the serum creatinine level reached 2 mg/dl post operatively with recovering creatinine levels after 7 days (Table 2).No AKI was reported. Neither 30days death nor major complications or major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were described. At mean follow-up of 24 months (range 18-27 months) no reinterventions were required, and renal function remained well preserved in all patients.

|

N=7 |

|

|

Male |

6 (85%) |

|

Female |

1 (14%) |

|

Smokers |

4 (57%) |

|

Hypertension |

7 (100%) |

|

Diabetes |

3 (42%) |

|

Dyslipidemia |

5 (71%) |

|

COPD |

0 (0%) |

|

Chronic Renal Failure |

0 (0%) |

|

Coronary artery disease |

1 (14%) |

|

Asa Score |

Pt 1 (II); Pt 2 (I); Pt 3 (III); Pt 4 (I); Pt 5 (II); Pt 6 (II). Pt 7 (II). |

Table 1: Risk Factors and Comorbidities.

Table 2: Renal Function.

Figure 2: Renal Arteries Reimplantation

Figure 3: Retroperitoneal Approch

Figure 4: Intraoperative result. Aorto - ipogastric by pass with left prostetic femoral jump.

Discussion

Owing to the limited state of knowledge, no firm recommendations can be made for the treatment of AAA with HSK. The surgeon should choose open or endovascular methods based on patient factors as well as according to personal preference and expertise. The association between HSK and AAA was first described in 1956 by Julian [5] and in 1957 Phelan et al. [6]. O hara et al. reported the largest series (19 patients) of patients presenting concomitant HSK and AAA, treated with an open approach in 31-year period [2]. Ferko et al in 1997 reported the first AAA in a HSK treated with EVAR [7]. There are several classifications to depict the different vascular varieties encountered in patients with HSK, such as those provided by Crawford [8], Papin [9], Boatman [10], and Eisendrath. The most used classification for HSK is proposed by Eisendrath et al. and describes five types of vascularization [11]. In type I, which accounts for 20% of cases, there is one renal artery supplying each side of the kidney; in type II, which accounts for 30% of cases, there is one renal artery supplying each side of the kidney with an aortic branch to the isthmus; in type III, which accounts for 15% of cases, there are two renal arteries supplying each side and one renal isthmus artery; in type IV, which accounts for 15% of cases, there are two renal arteries supplying each side, with one or more arising from the iliac arteries, including the isthmus branch; and in type V, which accounts for 20% of cases, there are multiple renal arteries originating from the aorta and the mesenteric and iliac arteries.

Precise pre-operative knowledge of the anomalous renal perfusion is fundamental for the successful planning and treatment of patients presenting with concomitant HSK and AAA. Some studies describe the use of methylene blue to define the exact perfusion pattern of the kidney [12]. Both the ESVS guidelines [13] and the American guidelines [14] recommend the preservation of the renal isthmus and anomalous renal arteries >3 mm in diameter [15,16]. Current ESVS guidelines and case series suggests [17] a retroperitoneal approach for patients requiring open surgical repair. Also, ESVS guidelines suggest an endovascular repair if anatomically feasible for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm with a coexisting horseshoe kidney [13]. However, in our series most of the cases (83,3 %) were managed using a middle laparotomy with a satisfactory aneurysm exposure, renal revascularization and without HSK isthmus division required. As many accessory renal arteries as possible should be reanastomosed to the prosthesis [2-11,15,16,18]. Starting from previous reported experience of Tshomba et al. [12,14,17,19-25], to prevent the onset of an AKI, in present series the renal arteries were perfused with Custodiol solution, despite no recommendation coming from current guidelines for HSK renal perfusion. The latter is a crystalloid solution with electrolyte concentrations like the intracellular environment, containing lower levels of sodium, calcium, potassium, and magnesium than lactated Ringer’s solution. These low electrolyte concentrations should reduce the cellular swelling, toxicity, and damage caused by the ischemic insult [19,20].There are many case reports that show the feasibility of endovascular treatment [3-13,15-21]or cases of hybrid repair trough re-implantation of aberrant renal artery followed by deployment of endograft [22-23].Repair has also been described using a fenestrated endograft and snorkel grafts [24].Obviously, EVAR is a good alternative option for patients who are unable to tolerate open AAA repair because of poor surgical condition; however, the optimal renal arteries management during endovascular procedures still remains a source of concern.

Conclusion

Open Surgical Repair of AAA with HSK is a feasible, effective, and safe technique at experienced centers. In our experience, surgical approach using perfusion with Custudiol still appears safer in fit patients to preserve renal functions. The use of Custodiol during open TAAA repair was safe and resulted in significantly lower rates of postoperative AKI compared with Ringer’s solution. These findings support safety and efficacy of Custodiol in this specific setting, which is currently off-label.

References

- Natsis K, Piagkou M, Skotsimara A, Protogerou V, Tsitouridis I, et al. (2014) Horseshoe kidney: a review of anatomy and pathology. Surg Radiol Anat 36: 517-526.

- O’Hara PJ, Hakaim AG, Hertzer NR, Krajewski LP, Cox GS, et al. (1993) Surgical management of aortic aneurysm and coexistent horseshoe kidney: review of a 31-year experience. J Vasc Surg 17: 940-947.

- Fabiani MA, González-Urquijo M, Riambau V, Vaquero Puerta C, Mosquera Arochena NJ, et al. (2019) EVAR Approach for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm with Horseshoe Kidney: A Multicenter Experience. Ann Vasc Surg 58: 232-237.

- Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, et al. (2007) Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 11: R31.

- Julian OC (1956) Diagnosis in arterial disease. Surg Clin North Am. 1956: 177-191.

- Phelan JT, Bernatz PE, Deweerd JH (1957) Abdominal aortic aneurysm associated with a horseshoe kidney: report of case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 32: 77-81.

- Ferko A, Krajina A, Jon B, Leško M, Vobořil Z (1997) Juxtarenal Aortic Aneurysm Associated With a Horseshoe Kidney: Transfemoral Endoluminal Repair. Arch Surg 132: 316-317.

- Crawford ES, Coselli JS, Safi HJ, Martin TD, Pool JL (1988) The impact of renal fusion and ectopia on aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg 8: 375-383.

- Papin E (1914) Anomalies congénitales du rein. Encycl franç, d’urol 1914: 227-322.

- Boatman DL, Cornell SH, Kölln CP (1971) The arterial supply of horseshoe kidneys. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 113: 447-451.

- Eisendrath DN, Phifer FM, Culver HB (1925) Horseshoe Kidney. Ann Surg 82: 735-764.

- Sieńko J, Kotowski MJ, Nowacki A, Romanowski M, Sulikowski T, et al. (2014) Methylene blue usage in horseshoe kidney graft separation: case report. Transplant Proc 46: 2923-2926.

- Wanhainen A, Verzini F, Van Herzeele I, Allaire E, Bown M, et al. (2019) Editor’s Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aortoiliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 57: 8-93.

- Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, Jackson BM, Lee WA, et al. (2018) The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 67: 2-77.e2.

- Chan YC, Qing KX, Ting AC, Cheng SW (2011) Endovascular infrarenal aneurysm repair in patients with horseshoe kidneys: case series and literature review. Vascular 19: 126-131.

- Davidović L, Marković M, Ilic N, Koncar I, Kostić D, et al. (2011) Repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the presence of the horseshoe kidney. Int Angiol 30: 534-540.

- De Caridi G, Massara M, Greco M, Mastrojeni C, Serra R, et al. (2015) Surgical Treatment of a Voluminous Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm with Horseshoe Kidney: Tips and Tricks. Ann Vasc Dis 8: 324-327.

- Stroosma OB, Kootstra G, Schurink GW (2011) Management of aortic aneurysm in the presence of a horseshoe kidney. Br J Surg 88: 500509.

- Tshomba Y, Kahlberg A, Melissano G, Coppi G, Marone E, et al. (2014) Comparison of renal perfusion solutions during thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 59: 623-633.

- Tinelli G, Sica S, Minelli F, Natola M, De Nigris F, et al. (2020) Horseshoe Kidney Protection with Histidine-Tryptophan-Ketoglutarate Solution during Surgical Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Ann Vasc Surg 63: 459.e5-459.e8.

- Sachsamanis G, Charisis N, Maltezos K, Galyfos G, Papapetrou A, et al. (2019) Management and therapeutic options for abdominal aortic aneurysm coexistent with horseshoe kidney. J Vasc Surg 69: 12571267.

- Kin K, Takano H, Nakagawa T, Shirakawa Y (2017) Hybrid Repair of an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Debranching with Endovascular Aneurysm Repair in a Patient with Horseshoe Kidney. Ann Vasc Dis 10: 41-43.

- Carnicelli AP, Doyle A, Singh M (2013) Hybrid repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm in a patient with a horseshoe kidney. J Vasc Surg 57: 1113-1115.

- Chaudhuri A (2011) Exclusion of an infrarenal AAA with coincident horseshoe kidney and renovascular anomalies is feasible using a standard stent-graft. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 41: 654-656.

- Kahlberg A, Tshomba Y, Baccellieri D, Bertoglio L, Rinaldi E, et al. (2023) CURITIBA Investigators. Renal perfusion with histidinetryptophan-ketoglutarate compared with Ringer’s solution in patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic open repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 165: 569-579.e5.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.