Neuropsychological Development Status in Children after Surgical Treatment of Congenital Heart Disease

by Shuantong Lin1*, Yulong Guan2*, Guoting Luo3, Juan Lu4, Jianyue Wang5

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Eastern Bund Healthcare, Shanghai, 202162, China

2Department of Extracorporeal Circulation, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100037, China

3Department of Radiology, Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 610072, Sichuan Province, China

4Department of Anaesthesiology, Shanghai Healthcare Center, Wuxi, 214000, Jiangsu Province, China

5Department of Anaesthesiology, Binzhou People's Hospital, Binzhou, 256600, Shandong Province, China

*Corresponding authors: Shuantong Lin, Department of Anaesthesiology, Eastern Bund Healthcare, Shanghai, 202162, China

Yulong Guan, Department of Extracorporeal Circulation, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, 100037, China

Received Date: 06 December, 2024

Accepted Date: 16 December, 2024

Published Date: 19 December, 2024

Citation: Lin S, Guan Y, Luo G, Lu J, Wang J (2024) Neuropsychological Development Status in Children after Surgical Treatment of Congenital Heart Disease. J Community Med Public Health 8: 487. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2228.100487

Abstract

Objective: Children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) usually show deficits in neurodevelopment, which may have detrimental influences on daily functioning, even on further school functioning. The survival of children with CHD in China has increased and the focus has been turned to the neuropsychological development of these children. This study is implemented to assess neuropsychological development status in children after surgical treatment of CHD in China. Methods: 89 children (51 males, 38 females; median month age 24 months, range 7-78 months) who received outpatient service reexamination in Fuwai Hospital from September 2015 to March 2016 after surgical treatment of CHD were recruited in this study and 90 normal children (55 males, 35 females; median month age 41 months, range 16-68 months) without any CHD were recruited as the control group. The children with CHD were divided into simple CHD group (RACHS-1 score ≤2) and complex CHD group (RACHS-1 score ≥3) according to RACHS-1 classification. Neuropsychological development status was measured according to Pediatric-psychological mental test scale developed by Capital institute of pediatrics, Beijing and statistical analysis was compared. Results: The results of measurements of neuropsychological development showed the normal children behaved better than the children with CHD (p<0.05). The simple CHD group showed better distribution of Development Quotient (DQ) than the complex CHD group (p=0.032) and there was no difference between the normal control group and the simple CHD group (p=0.420) in the distribution of DQ. Multivariate regression analysis indicated that younger age at cardiac surgery, lower preoperative Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), higher preoperative creatinine (Cr) and prolonged duration of Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) accounted for lower scores in the subscales (p<0.05). Conclusions: Distinct neuropsychological difficulties could be present especially in the children with complex CHD following surgical treatment. Younger age at cardiac surgery, preoperative BUN, Cr and CPB duration could be used as good predictors for long-time neuropsychological development. Multiple measures to assess neuropsychological outcomes of CHD children should be implemented in different hospitals in China.

Keywords: Congenital heart disease; Child; Neuropsychological development; Cardiac surgery

Abbreviations: CHD: Congenital Heart Disease; BUN: Blood Urea Nitrogen; Cr: Serum Creatinine; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; CPB: Cardiopulmonary Bypass; CVP: Central Venous Pressure; SpO2: Pulse Oxygen Saturation; PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit; INET: Infants Neuropsychological Examination Table; DQ: Development Quotient; RACHS-1: Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery-1; SD: Standard Deviation; SV: Single Ventricle; HLHS: Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome; TGA: Transposition of the Great Arteries; IQ: Intelligence Quotient

Introduction

It is reported that congenital heart disease influences 7-9‰ new-borns in Europe, Asia, and North America, about 25% of whom will need surgery in early life [1]. Currently, with the perioperative survival rate > 90% in neonates undergoing cardiac surgery, the focus has turned to the neuropsychological developmental outcomes and 30-50% of the neonates who underwent complex open-heart surgery would experience trouble in general intelligence, language, gross and fine motor function during infancy [2]. It is also obvious that at the age of school entry, those children would show deficits in cognition, memory, language, reading, mathematics, visual-motor integration and executive function, which is more frequent than the general population [3]. Nowadays, data of neuropsychological development in children with CHD after surgery treatment is not rich in China, so the children who received CHD surgery in Fuwai Hospital were examined and the postoperative neuropsychological development status of CHD children and the factors affecting neuropsychological development were investigated in this study.

Methods

Children population

100 children (56 males, 44 females) age 7 to 78 months who received congenital heart surgeries in Fuwai Hospital from 2009 to 2015 were eligible to participate in neuropsychological examination between September 2015 and March 2016. Exclusion criteria for enrolment were as follows: genetic abnormalities; extremely low gestational age new-borns and premature infant; history of perinatal asphyxia and hyperbilirubinemia; history of central nervous system diseases, such as ischemic encephalopathy, encephalitis, meningitis and epilepsy, cerebral dysplasia. Over the same period, 90 normal children (55 males, 35 females) age 16 to 68 months were chosen from nursery schools or kindergartens and the test results of them were regarded as control. The normal children were free from congenital heart diseases and the exclusion criteria were the same as above. Informed consent was obtained from all parents and the examination was performed under parental supervision.

Data collection

Preoperative parameters including month age at surgery, body weight, gender, haemoglobin, platelet count, blood glucose, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), serum albumin, serum creatinine (Cr) and Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) were collected. Intraoperative parameters included Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) time, aortic cross-clamping time, nadir nasopharyngeal temperature and the lowest Central Venous Pressure (CVP) before CPB. Postoperative parameters including mechanical ventilation time, postoperative nadir pulse oxygen saturation (SpO2), postoperative Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) stay time and postoperative hospital stay time were recorded. All of the operations were performed with full-flow extracorporeal circulation under mild (32 to 34°C) to moderate hypothermia (26 to 28°C).

Assessment of neuropsychological developmental outcomes

The same trained and licensed examiner assessed the children with Infants Neuropsychological Examination Table for children aged 0-6 (hereunder referred to INET) provided by the Capital Pediatrics Research Institute. It comprises five subscales: gross motor, fine motor, adaptability, language and social behavior. Mental age is calculated according to the five subscales scores and it equals to a fifth of sum of the five subscales scores. When referred to development quotient (DQ), it is calculated as 100 multiplied by the result of the mental age divided by the actual month age. As for DQ, supernormal neuropsychological development is defined in this study to be indicated by a score >130, good neuropsychological development is defined to be indicated by a score 120-130, smart neuropsychological development with a score 110-120, medium neuropsychological development with a score 90-110, slow with a score 80-90, borderline mental retardation with a score 70-80 and hypophrenia with a score <70.

Classification method of CHD surgeries

The risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery-1(RACHS-1)method is commonly used among pediatric population clinically and the congenital heart surgeries are classified into 1 to 6 according to this method [4]. In this study, there was no surgery ranked equal or greater than 5, so the children received CHD surgeries were divided into simple CHD group (RACHS-1 score less than or equal to 2) and complex CHD group (RACHS-1 score equal or greater than 3).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were presented as mean with Standard Deviation (SD) and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Normally distributed data were compared with the Student t test and when a normal distribution for continuous data was not assumed, Kruskal-Wallis correlation was used to analyze the correlation between different variables. ANOVA analysis was performed to predict the differences of neuropsychological development among simple CHD group, complex CHD group and normal group. Relationships between INET subscales and perioperative parameters were evaluated by forward stepwise multivariable regression analysis. Results were considered statistically significant if P values were less than .05.

Results

Children characteristics

Of 100 children with CHD after surgical treatment recruited in this study, 11 did not cooperate with the examiner and did not undergo the neuropsychological test, so 89 children with CHD after surgical procedure in FuWai Hospital received examination between September 2015 and March 2016. According to the classification of RACHS-1 method, 53 subjects were in the simple CHD group and 36 were in the complex CHD group. Demographic and clinical data of the simple CHD group and the complex CHD group are presented in Table 1.

|

Simple CHD Group (n=53) |

Complex CHD Group (n=36) |

P-value |

|

|

Sex, male/female, n |

34/19 |

17/19 |

0.116 |

|

Age at surgery, m, mean ± SD |

24.03 ± 19.85 |

22.55 ± 21.05 |

0.738 |

|

Weight at surgery, kg, mean ± SD |

11.24 ± 4.64 |

10.14 ± 4.51 |

0.272 |

|

Preoperative Hb, g/L, mean ± SD |

123.23 ± 19.81 |

121.81 ± 15.59 |

0.719 |

|

Preoperative PLT,x10^9/L, mean ± SD |

314.26 ± 96.84 |

286.33 ± 113.64 |

0.217 |

|

Preoperative BG, mmol/L, mean ± SD |

4.38 ± 0.87 |

4.42 ± 0.78 |

0.812 |

|

Preoperative BUN, mmol/L, mean ± SD |

4.01 ± 1.13 |

4.31 ± 1.62 |

0.354 |

|

Preoperative Cr, mmol/L, mean ± SD |

30.10 ± 6.55 |

31.13 ± 9.96 |

0.556 |

|

Preoperative Alb, g/L, mean ± SD |

44.39 ± 2.88 |

42.85 ± 3.64 |

0.035 |

|

Preoperative LVEF, %, mean ± SD |

66.95 ± 5.30 |

63.99 ± 9.77 |

0.068 |

|

Intraoperative CPB, min, mean ± SD |

72.81 ± 40.41 |

99.47 ± 62.46 |

0.016 |

|

Intraoperative aortic clamp, min, mean ± SD |

43.24 ± 31.50 |

61.72 ± 41.63 |

0.021 |

|

Intraoperative nadir nasopharyngeal temperature, °C, mean ± SD |

30.67 ± 2.29 |

30.33 ± 1.74 |

0.462 |

|

Intraoperative lowest CVP before CPB, mmHg, mean ± SD |

3.06 ± 1.23 |

2.75 ± 1.25 |

0.255 |

|

Postoperative ventilation, h, mean ± SD |

15.19 ± 12.87 |

19.34 ± 17.02 |

0.194 |

|

Postoperative lowest oxygen saturation, %, mean ± SD |

97.57 ± 2.34 |

97.50 ± 3.24 |

0.911 |

|

Postoperative ICU stay, d, mean ± SD |

40.81 ± 51.06 |

64.06 ± 74.48 |

0.084 |

|

Postoperative hospital stays, d, mean ± SD |

12.29 ± 7.80 |

15.50 ± 7.32 |

0.103 |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical data of the simple CHD group and the complex CHD group.

Comparison on perioperative parameters between complex and simple CHD group

The complex CHD group did not differ significantly in terms of month age at surgery from the simple CHD group (22.55 + 21.05 vs. 24.03 + 19.85, p=0.738), suggesting that there was no direct relationship between the surgery timing and the severity of congenital heart diseases. Possibly, the surgery timing was more relevant with the progress of the diseases or the parental knowledge of the diseases or the doctors’ medical advice. The complex CHD group differed on CPB time and aortic cross-clamping time from the simple CHD group (p<0.05), suggesting longer surgery time and more accurate hemodynamic management were necessary in the complex CHD group. The complex CHD group differed on preoperative serum albumin from the simple CHD group (42.85 + 3.64 vs. 44.39 + 2.88, p=0.035), but there was no significant difference on the body weight between the complex CHD group and the simple CHD group on the day of surgery (10.14 + 4.51 vs. 11.24 + 4.64, P=0.272), which indicated that the children in the complex CHD group might suffer from poorer nutrient reserves and more interstitial oedema or water retention problems in vivo. Under this circumstance, more detailed preoperative preparation and more precise intraoperative monitoring would be helpful for the complex CHD group.

Comparison on INET subscales between CHD and normal children

Compared with the normal children, the subscale scores of the children with CHD decreased obviously. When it referred to the gross and fine motor domains, the children with CHD scored lower than the normal children (p<0.05), such as poor coordination between hands and feet, suggesting poor cerebellar development might exist in the children with CHD. When it referred to the language domain, the children with CHD lagged behind the normal children (p<0.001), mostly in imitation of pronunciation, coherence and comprehension, suggesting retardation in the development of auditory speech area and motor language area might exist in the children with CHD. The children with CHD got less scores than the normal children in the items of adaptation ability and social behavior (p<0.05) and they were more likely with excessive anxiety, poor self-care ability and poor self-expression ability, indicating that the children with CHD could be with depressive disorder, which need early intervention. The children with CHD differed significantly in terms of DQ from the normal children (90.67 + 11.41 vs. 96.48 + 7.54, p<0.001), suggesting that strengthen training and appropriate psychological intervention should be imposed on the children with CHD. Outcomes for all the items’ scores in the test scale between the children with CHD and the normal children were shown in Table 2.

|

Subscales scores |

Normal group n=90 |

CHD group n=89 |

P-value |

|

Gross motor |

40.30 ± 16.40 |

30.60 ± 20.22 |

0.001 |

|

Fine motor |

39.44 ± 16.16 |

29.66 ± 20.44 |

< 0.001 |

|

Adaptability |

40.08 ± 15.98 |

30.61 ± 19.90 |

0.001 |

|

Language |

40.24 ± 16.35 |

30.32 ± 20.24 |

< 0.001 |

|

Social behavior |

39.52 ± 15.35 |

30.96 ± 21.06 |

0.002 |

|

DQ |

96.48 ± 7.54 |

90.67 ± 11.41 |

< 0.001 |

Table 2: Outcomes for all the subscales scores in the test scale between the children with CHD and the normal children (mean ± SD).

Influence of Surgery types on INET subscale scores

To make further analysis about the influence of CHD surgery types on the results of the INET, analysis of variance was used to compare the two CHD groups and the normal group. Both of the two CHD groups got less scores in the INET than the normal group (p<0.05). The complex CHD group lagged behind the normal group (86.74 ± 11.93 vs. 96.48 ± 7.54, p<0.001) and the simple CHD group (86.74 ± 11.93 vs. 93.34 ± 10.32, p=0.001) in DQ scores, suggesting that the more complex the CHD surgery types, the lower neuropsychological development, which need evaluating more rigorously. It could provide reasonable intervention and avoid further damage on the neuropsychological development by effective evaluation. There was no significant difference in the DQ scores between the simple CHD group and the normal group (p=0.056), suggesting that the simple type CHD surgery could not influence the neuropsychological development dramatically. Outcomes for all the subscale scores in the test scale between the two CHD group and the normal group were shown in Table 3.

|

Subscales scores |

Simple CHD group n=53 |

Complex CHD group n=36 |

Normal group n=90 |

|

Gross motor |

32.31 ± 20.31 |

28.08 ± 20.10 |

40.30 ± 16.40 |

|

Fine motor |

31.17 ± 20.52 |

27.43 ± 20.40 |

39.44 ± 16.16 |

|

Adaptability |

32.21 ± 19.85 |

28.26 ± 20.01 |

40.08 ± 15.98 |

|

Language |

32.32 ± 20.59 |

27.38 ± 19.64 |

40.24 ± 16.35 |

|

Social behavior |

32.68 ± 21.43 |

28.42 ± 20.53 |

39.52 ± 15.35 |

|

DQ |

93.34 ± 10.32 |

86.74 ± 11.93 |

96.48 ± 7.54 |

Table 3: Outcomes for all the subscales scores between the two CHD group and the normal group (mean ± SD).

Difference on DQ distribution between CHD and normal children

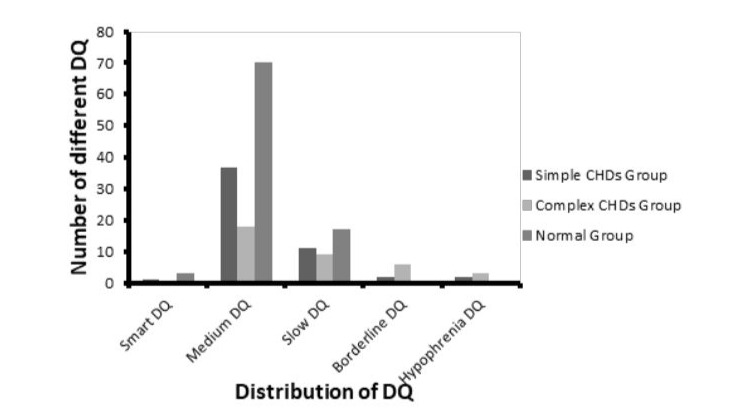

The Kruskal-Wallis correlation was performed to assess the difference in DQ distribution between the two CHD groups and the normal group. The proportion of children whose DQ were below the moderate level in the complex CHD group was higher than that in the normal group (50% vs. 18.9%, p<0.001) and the simple CHD group (50% vs. 28.3%, p=0.032). The simple CHD group did not differ in the DQ distribution from the normal group (p=0.420). The results suggested that neuropsychological development in the children after simple type CHD surgery treatment were close to the normal children. However, with the surgery difficulty increasing, the proportion of DQ retardation significantly increased. The distribution of DQ in different groups was shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The distribution of DQ in different groups.

Risk factors on neuropsychological development impairment

Association between INET subscale scores and perioperative parameters were evaluated by forward stepwise multivariable regression (Table 4). Full-scale scores were correlated with the month age at surgery (p<0.05), suggesting that small month age at surgery could influence the long-time neuropsychological development. Relationship was found between preoperative BUN and the full-scale scores (p<0.05), however the reason why increased BUN was correlated with high scores was indefinite, it might be related to preoperative nutritional reserve. Relationship was found between preoperative Cr and the full-scale scores (p<0.05), suggesting that preoperative renal function could increase water retention, which would further influence the central nervous system. With longer CPB time, the social behavior item scored lower (p=0.041), suggesting that long-time non-pulsatile blood flow would damage the brain development.

|

Risk factors |

Gross motorp-value |

Finemotorp-value |

Adaptability p-value |

Language p-value |

Social behaviorp-value |

|

RACHS-1 score |

0.416 |

0.427 |

0.500 |

0.346 |

0.188 |

|

Age at surgery |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

|

Body weight |

0.536 |

0.757 |

0.825 |

0.758 |

0.894 |

|

Hemoglobin |

0.422 |

0.984 |

0.360 |

0.715 |

0.699 |

|

Platelet count |

0.493 |

0.614 |

0.720 |

0.879 |

0.729 |

|

Blood glucose |

0.394 |

0.240 |

0.694 |

0.556 |

0.856 |

|

BUN |

0.006 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.004 |

|

Alb |

0.337 |

0.430 |

0.347 |

0.216 |

0.804 |

|

Cr |

0.040 |

0.015 |

0.005 |

0.004 |

0.016 |

|

LVEF |

0.271 |

0.110 |

0.136 |

0.071 |

0.161 |

|

CPB time |

0.087 |

0.087 |

0.072 |

0.061 |

0.041 |

|

Aortic cross-clamping time |

0.127 |

0.186 |

0.150 |

0.110 |

0.645 |

|

Nadir nasopharyngeal temperature |

0.089 |

0.323 |

0.335 |

0.332 |

0.768 |

|

CVP |

0.849 |

0.732 |

0.693 |

0.722 |

0.558 |

|

Mechanical ventilation time |

0.338 |

0.331 |

0.204 |

0.466 |

0.984 |

|

SpO2 |

0.231 |

0.287 |

0.199 |

0.372 |

0.117 |

|

PICU stay |

0.568 |

0.752 |

0.818 |

0.435 |

0.075 |

|

Postoperative hospital stays |

0.469 |

0.957 |

0.505 |

0.702 |

0.732 |

Table 4: Results of forward stepwise multivariable regression.

Discussion

Over the past 20 years, with advances in surgical techniques and improvement in perioperative management, the survival of children with complex CHD after surgery treatment has increased. Meanwhile, more and more concern has been focused on the neuropsychological retardation of these children [5]. Some studies [6-8] have reported early neurodevelopmental outcomes following congenital heart surgery in neonates and infants prospectively. It could provide valuable anticipatory guidance for patients, families, teachers, and therapists by neurodevelopmental assessments and quality of life assessments [9]. With early identification of risk factors influencing neuropsychological development and treatment of developmental disorder and delays, children with CHD may have the best chance to achieve their full potential, which will further help the children with CHD develop better to adapt to the society [10]. It will also reduce the economic burden of these children’s family, which is of vital importance in China.

In 1998, Kathy Jenkins and 11-member national panel of pediatric cardiologists and cardiac surgeons created the RACHS-1 method, to place surgical procedures into six risk categories. Cardiac surgeries during which more than one procedure are performed simultaneously are placed in the risk category of the highest risk procedure [11]. In this study, RACHS-1 method was used to classify different congenital heart surgery into different groups.

Children with Single Ventricle (SV) physiology are at risk for neurodevelopmental impairment early in life and neurocognitive impairment as they age. Mechanisms that could contribute to increased potential for cognitive impairment may include baseline brain dysmaturation beginning in utero, subsequent acquired injury occurring in early childhood from staged surgeries and pathophysiologic factors related to SV physiology itself throughout the lifespan as new arrhythmias, heart failure, and other issues may develop [12]. Similarly, it was found that with the RACHS-1 scores increasing, the DQ scores decreased significantly. A meta-analysis conducted by Feldmann M et al. [8] on 3645 children with CHD reported Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) and univentricular CHD cohorts performed significantly worse than atrial and ventricular septum defect cohorts in total IQ, which contained not only verbal IQ, but also performance IQ. An older age at assessment was associated with lower IQ scores in cohorts with transposition of the great arteries (TGA). Consistent with Feldmann M, it was found that the younger the children received CHD surgery, the lower scores in the INET in this study. Although the scores in the INET elevated with the increase of age, which was in accordance with the rule of intelligence development of the children, the influence of the complexity of CHD surgery on the neuropsychological development should not be neglected.

Previous studies [2,13-15] reported that postoperative mixed venous oxygen saturation, days in the intensive care unit, length of stay in hospital and complications such as epilepsy, hypotension, arrhythmia or sepsis were risk factors associated with neurologic, motor and developmental deficits in children after CHD surgeries. In this study, multiple stepwise regression analysis suggested that preoperative BUN, Cr and intraoperative CPB time associate with INET scores. With the increase of preoperative Cr and CPB time intraoperative CPB time, the scores decreased dramatically. Conversely, with the decrease of preoperative BUN, the scores increased significantly, but the reason was unclear. After evaluation on 340 pediatric patients with chronic kidney diseases, Mendley SR et al. [16] found that the brains’ attention and execution in these patients became poor. Silveira RC, et al. [17] reported that adequate protein intake and energy supply could protect brain neurons with immune-modulatory and/or anti-inflammatory effects and improve brain development in preterm infants with white matter injury.

Latal B, et al. [18] evaluated 48 adolescents undergoing early CPB surgery for CHD and found 10% lower total hippocampal volumes compared with controls. Reduced hippocampal volumes correlated with lower total intelligence quotient (IQ). Similarly, Razzaghi, et al. [20] analyzed 420 children with CHD and 180048 children without CHD, found that children with CHD were more likely accompanied with autism spectrum disorder, speech and language problems. In this study, children with CHD received surgery at a relatively younger month-age (23.40 + 20.24), despite the children in the complex CHD group showed a certain degree of anxiety in the process of evaluating adaptability and social behavior, but whether the children with CHD would present with autism spectrum disorder or depression still need long-term follow-up.

Limitation

The current study has certain limitations. The study was conducted in one single hospital in China and the sample was not large. Another limitation is the lack of information about the preoperative INET scores of the CHD children, the parents’ economic status, educational background. The CHD children did not receive cerebral MRI during postoperative period, so there was doubt about whether the brain got hurt or not during CPB. In addition, during the postoperative period, the circulating cytokines, thyroid function, liver function, renal function, adequacy of vasoregulation or other factors that could infect the development of brain were not measured. However, this study highlighted the influence of congenital heart surgeries on the long-time neuropsychological development.

Conclusion

Children with CHD after surgery will demonstrate neuropsychological impairments especially those received more difficult bypass surgery. Children’s age at surgery, preoperative BUN and Cr and intraoperative CPB duration could be used as good predictors for long-time neuropsychological development. This study underlines the importance of timely and long-time assessments in children with CHD after surgery. Comprehensive examinations, counselling and therapies are also needed under this circumstance.

Author Contributions

Supervision: Shuantong Lin, Yulong Guan.

Writing – original draft: Shuantong Lin, Juan Lu.

Writing – review & editing: Jianyue Wang, Yulong Guan.

Statistical analysis: Shuantong Lin, Yulong Guan.

References

- Su Z, Zou Z, Hay SI, Liu Y, Li S, et al. (2022) Global, regional, and national time trends in mortality for congenital heart disease, 1990-2019: An age-period-cohort analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. EClinicalMedicine 43: 101249.

- Lin S, Su X, Cao D (2024) Current research status and progress in neuropsychological development of children with congenital heart disease: A review. Medicine (Baltimore) 103: e40489.

- Farr SL, Downing KF, Riehle-Colarusso T, Abarbanell G (2018) Functional limitations and educational needs of children and adolescents with heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis 13: 633-639.

- Nakae K, Ueno K, Shiokawa N, Takahashi Y, Kawamura J, et al. (2022) Pediatric Patients Undergoing a Fontan Operation or with a High RACHS-1 Score Require Monitoring for Chronic Kidney Disease in Early Childhood. Pediatr Cardiol 43: 1020-1028.

- Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, et al. (2020) Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 76: 2982-3021.

- Diller GP, Arvanitaki A, Opotowsky AR, Jenkins K, Moons P, et al. (2021) Lifespan perspective on congenital heart disease research: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 77: 2219-2235.

- Billotte M, Deken V, Joriot S, Vaksmann G, Richard A, et al. (2021) Screening for neurodevelopmental disorders in children with congenital heart disease. Eur J Pediatr 180: 1157-1167.

- Feldmann M, Bataillard C, Ehrler M, Ullrich C, Knirsch W, et al. (2021) Cognitive and Executive Function in Congenital Heart Disease: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 148: e2021050875.

- Feng J, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Liu T, Ma L, et al. (2023) Evaluation of neurodevelopmental impairments and risk factors in children following cardiac surgery: the first cohort from China. JTCVS Open 14: 462-471.

- Lenoir M, Beretti T, Testud B, Resseguier N, Gauthier K, et al. (2023) Impact of cardiac surgical timing on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of newborns with Complex congenital heart disease (CHD). Front Pediatr 11: 1003585.

- Allen P, Zafar F, Mi J, Crook S, Woo J, et al. (2022) Risk Stratification for Congenital Heart Surgery for ICD-10 Administrative Data (RACHS-2). J Am Coll Cardiol 79: 465-478.

- Selvanathan T, Smith JMC, Miller SP, FieldTS (2022) Neurodevelopment and Cognition Across the Lifespan in Patients with Single-Ventricle Physiology: Abnormal Brain Maturation and Accumulation of Brain Injuries. Can J Cardiol 38: 977-987.

- Simpao AF, Randazzo IR, Chittams JL, Burnham N, Gerdes M, et al. (2023) Anesthesia and Sedation Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Infants Undergoing Congenital Cardiac Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Anesthesiology 139: 393-404.

- Stegeman R, Nijman M, Breur JMPJ, Groenendaal F, Haas F, et al. (2022) CeRebrUm and CardIac Protection with ALlopurinol in Neonates with Critical Congenital Heart Disease Requiring Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CRUCIAL): study protocol of a phase III, randomized, quadruple-blinded, placebo-controlled, Dutch multicenter trial. Trials 23: 174.

- Shevell AH, Sahakian SK, Nguyen Q, Fontela P, Rohlicek C, et al. (2020) Associations Between Postoperative Management in the Critical Care Unit and Adolescent Developmental Outcomes Following Cardiac Surgery in Infancy: An Exploratory Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 21: e1010-e1019.

- Mendley SR, Matheson MB, Shinnar S, Lande MB, Gerson AC, et al. (2015) Duration of chronic kidney disease reduces attention and executive function in pediatric patients. Kidney Int 87: 800-806.

- Silveira RC, Corso AL, Procianoy RS (2023) The Influence of Early Nutrition on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants. Nutrients 15: 4644.

- Latal B, Patel P, Liamlahi R, Knirsch W, Tuura RO, et al. (2016) Hippocampal volume reduction is associated with intellectual functions in adolescents with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Res 80: 531-537.

- Razzaghi H, Oster M, Reefhuis J (2015) Long-term outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: National Health Interview Survey. J Pediatr 166: 119-124.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.