Neuro-Endoscopic Removal with a Small Craniotomy for Acute Subdural Hematoma in Middle Aged and Elderly Adults

by Feng Wang, Han Luo*

Chongqing University Fuling Hospital, Chongqing Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Institute, China

*Corresponding author: Han Luo, Chongqing University Fuling Hospital, Chongqing Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Institute. Fuling City, Chongqing 408000, China.

Received Date: 23 July, 2025

Accepted Date: 06 August, 2025

Published Date: 08 August, 2025

Citation: Wang F, Luo H (2025) Neuro-Endoscopic Removal with a Small Craniotomy for Acute Subdural Hematoma in Middle Aged and Elderly Adults. J Med Biomed Discoveries 7: 142. https://doi.org/10.29011/2688-8718.100142

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of neuro-endoscopic-assisted small bone window craniotomy for treating acute subdural hematoma in middle aged and elderly adults. Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of clinical data from six middle aged and elderly adults with acute subdural hematoma who underwent neuroendoscopic-assisted small bone window craniotomy at our hospital between October 2021 and June 2024. An arc incision of about 12cm was made on the frontal-parietal region, and a water-drop-shaped bone window of approximately 3cm x 6cm was taken. The acute subdural hematoma was cleared under the assistance of a neuro-endoscope. Results: All patients achieved satisfactory hematoma clearance, with an overall clearance rate exceeding 96%. The duration of the surgery ranged from 105 to 170 minutes. Intraoperative hemostasis was satisfactory, and there were no complications such as postoperative rebleeding. Conclusion: In conclusion, neuroendoscopic-assisted small bone window surgery is effective for appropriate middle aged and elderly adults with acute subdural hematoma. It provides a clear surgical view, effectively clears the hematoma, accurately controls bleeding, reduces surgery duration, and minimizes secondary injuries.

Keywords: Acute subdural hematoma; Endoscopic surgery; Hematoma evacuation

Introduction

Acute subdural haematoma (ASDH) is a serious condition related to traumatic brain injury, known for high mortality rates and significant long-term cognitive issues [1]. ASDH primarily occurs in middle-aged and elderly individuals [2]. The standard treatment for ASDH is to remove the hematoma using a large craniotomy [3]. Craniotomy is often burdensome for patients due to significant bleeding, a large incision, and lengthy surgery time. In contrast, neuroendoscopy hematoma evacuation is a minimally invasive procedure. This minimally invasive surgery may potentially offset the drawbacks of craniotomy. Recent reports on endoscopic hematoma removal via small craniotomy for ASDH mostly focus on elderly patients, with few studies involving middle-aged individuals [4-7]. Here, we present a case series involving six middle aged and elderly adults with ASDH who underwent endoscopic hematoma removal via a small craniotomy.

Materials and Methods

Research subject

Inclusion criteria

- On computed tomographic (CT) scan, the thickness of intracranial hematoma is greater than 10mm or the midline structural deviation of brain tissue is greater than 5mm.

- Middle-aged adults: six cases were included in the study, with ages ranging from 42 to 58 years and an average age of 53 years. 3. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score greater than 9.

Exclusion criteria include

- Intracerebral hematomas that require surgical intervention;

- Presence of other multiple organ injuries.

Surgical Method

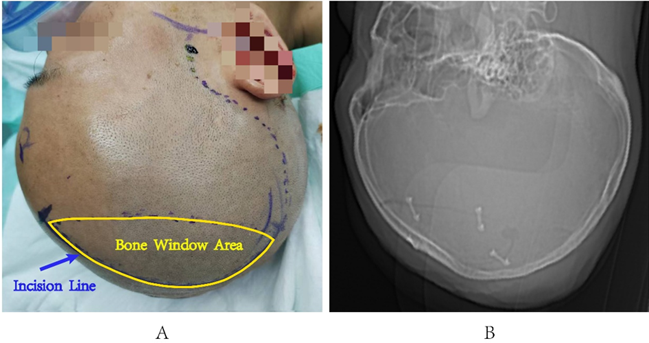

A semi-circular incision is made starting at the hairline adjacent to the midline of the forehead, extending around the vertex tubercle posteriorly, and the bone flap is shaped like a teardrop (see Figure 1A). The dura mater is retracted towards the midline, and a zero-degree endoscope is inserted. The subdural hematoma is then cleared under direct vision, allowing for the identification of the bleeding site. Bipolar electrocoagulation is used for hemostasis, and the bone flap is restored postoperatively.

Figure 1: Incision Design Schematic Diagram. A. Surgical incision design; B. CT reveals the shape of the bone flap

Result

All patients expressed satisfaction with the evacuation of their hematomas, achieving a clearance rate exceeding 96%. Furthermore, in three cases, no specific bleeding site was identified; however, precise hemostasis was successfully achieved using neuroendoscopy. The midline structures were restored to normal after surgery, and there were no complications, such as infarction or delayed bleeding. For specific details, please refer to Table 1.

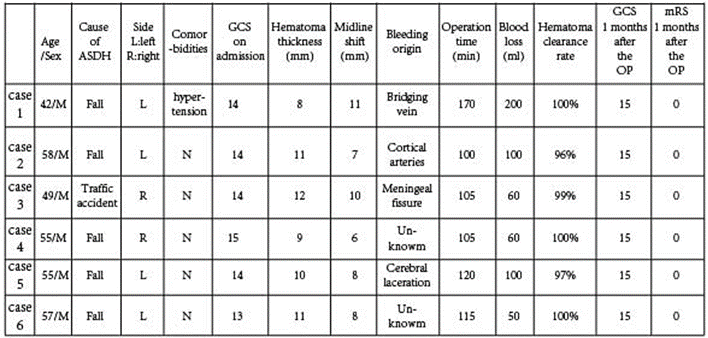

Table 1: Clinical Data and prognosis of 6 Patients.

Typical Case 1

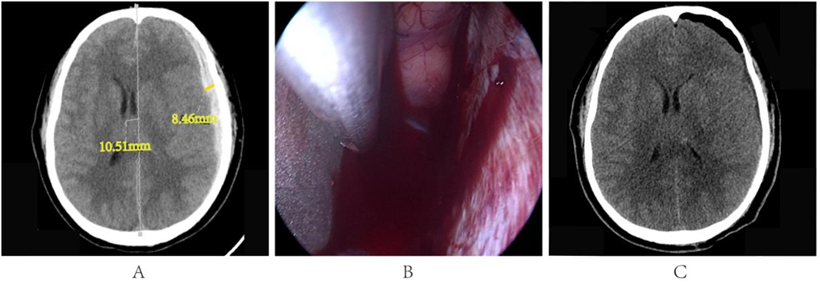

A 42-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital after experiencing dizziness and a headache that lasted for one hour following a fall. Upon admission, the patient was drowsy and had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14.A CT scan revealed an acute subdural hematoma on the left side, with a thickness of approximately 8mm and a midline shift of about 11mm (Figure 2A). Bleeding was observed from the bridging veins (Figure 2B). Most of the hematoma has been cleared (Figure 2C).

Figure 2: A. Preoperative cranial CT results; B. Bridging vein bleeding; C. Postoperative cranial CT results.

Typical Case 2

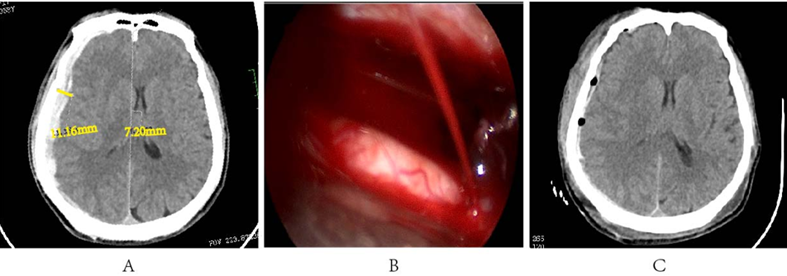

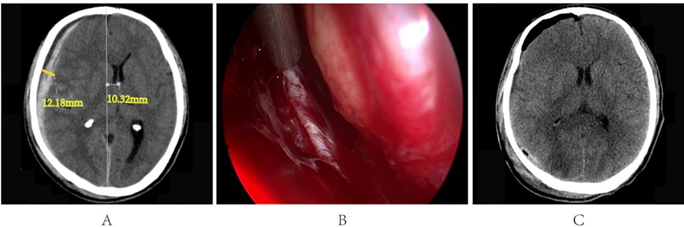

A 58-year-old male was admitted to the hospital after experiencing altered consciousness for 2 hours following a fall injury. Upon admission, the patient exhibited somnolence, as indicated by a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14. A CT scan revealed an acute right-sided subdural hematoma, measuring approximately 10 mm in thickness and causing a midline shift of about 7 mm (Figure 3A). Bleeding was observed to originate from a cortical artery (Figure 3B). Most of the hematoma has been cleared (Figure 3C).

Figure 3: A. Preoperative cranial CT results; B. Cortical artery bleeding; C. Postoperative cranial CT results.

Typical Case 3

A 49-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital following a traffic accident. He reported a headache lasting over an hour, exhibited drowsiness upon admission, had right cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea, and scored 14 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Dural tear with bleeding (Figure 4A-B). Most of the hematoma has been cleared (Figure 4C).

Figure 4: A. Preoperative cranial CT results; B. Dural tear with bleeding; C. Postoperative cranial CT results.

Discussion

Neuroendoscopy offers a unique field of view and close-up observation, greatly minimizing brain tissue damage and is widely used for treating chronic and subacute subdural hematomas [8-10]. The introduction of neuroendoscopic technology represents a new, safer, and more precise phase in surgical treatment. It not only enables surgeons to observe the lesion area with unmatched clarity but also significantly reduces trauma and risks during the procedure.

There is still ongoing debate within the medical community about the best treatment for acute subdural hematoma [11]. It is recommended that patients with a hematoma thickness exceeding 10mm or a midline shift greater than 5mm should consider undergoing surgical treatment [12,13]. However, the surgical options currently available include hematoma evacuation combined with decompressive craniectomy, cranioplasty, hematoma percutaneous drainage, and neuroendoscopic surgery, among others. Each method has its unique advantages and disadvantages, and there is no clear consensus on the optimal surgical approach [13].

Acute subdural hematoma is located in the subdural space, which happens to be a potential space for endoscopic procedures. Therefore, the use of neuroendoscopic assistance to perform small craniotomy surgery for hematoma evacuation is also a viable treatment option. Yokosuka et al. suggest that for patients over 70 years of age with stable bleeding and no risk of hematoma expansion, neuroendoscopic treatment can be adopted [14]. Masahito and Ryota et al. also confirmed that small craniotomy neuroendoscopic treatment is effective for acute subdural hematoma in elderly patients [4,5].

Kuge A was the first to adopt neuroendoscopic small bone window surgery in the treatment of young patients with acute subdural hematoma and achieved success. He believes that sufficient subdural compensatory space is the key factor to ensure the success of this surgery [15]. All six patients in our surgery were under the age of 60. During the operation, the endoscope was implanted into the cavity formed by the compression of the hematoma on the brain tissue, and the temporal edge of the bone window was adjusted to a high point position by changing the body position, utilizing the natural sagging of the brain tissue, thereby obtaining sufficient surgical operating space. The average thickness of the hematoma in these six patients was about 10mm, fully meeting the operating space conditions required for endoscopic surgery.

Sun-Chul et al. suggest: Compare with endoscopically via a burr hole, a small craniotomy on the superior temporal line along the coronal suture provides a sufficient window for the procedure [7]. Therefore, we have also modified the incision, adopting a curved incision on the frontal-parietal region, with the bone flap shaped like a teardrop, making it easier for the endoscope to reach the temporal and occipital areas, and to clear the hematoma. In the event of intraoperative malignant brain herniation or difficulty in hemostasis, it is also convenient to expand the bone flap in a timely manner.

We believe that strict preoperative assessment to avoid acute brain swelling during surgery is the key to success or failure. The space occupied by the hematoma itself is sufficient for endoscopic procedures, which requires experienced doctors to develop personalized surgical plans based on the situation [16].

Conclusions

Although the standard treatment for ASDH is craniotomy, endoscopic surgery may be useful in some cases. Further experiences are needed for safe endoscopic surgery for middle aged and elderly adults’ patients as a minimally invasive treatment.

References

- Maas AIR, Menon DK, Adelson PD, Andelic N, Bell MJ, et al. (2017) Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research[J]. Lancet Neurol 16: 987–1048.

- Leitgeb J, Mauritz W, Brazinova A, Janciak I, Majdan M, et al. (2012) Outcome after severe brain trauma due to acute subdural hematoma[J]. J Neurosurg 117(2): 324-333.

- Hiroshi K, Toshiaki H, Takayuki H, Motonobu K, Atsuhiro N, et al. (2014) Surgical management of traumatic acute subdural hematoma in adults: a review[J]. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 54(11): 887-94.

- Masahito K, Yukinari K, Akihiro N, Keiko K, Yasunaga Y, et al. (2020) Fifteen Cases of Endoscopic Treatment of Acute Subdural Hematoma with Small Craniotomy under Local Anesthesia: Endoscopic Hematoma Removal Reduces the Intraoperative Bleeding Amount and the Operative Time Compared with Craniotomy in Patients Aged 70 or Older[J]. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 60(9): 439-449.

- Ryota T, Yoshiaki K, Yoshiki N (2016) Neuroendoscopic Removal of Acute Subdural Hematoma with Contusion: Advantages for Elderly Patients[J]. Case Rep Neurol Med 2016: 2056190.

- Ichimura S, Takahara K, Nakaya M, Keisuke Y, Yoichi M et al. (2019) Neuroen doscopic hematoma removal with a small craniotomy for acute subdural hematoma[J]. J Clin Neurosci 61: 311–314.

- Sun Chul H, Dong S (2019) Endoscopic Treatment of Acute Subdural Hematoma with a Normal Small Craniotomy[J]. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 81(1): 10-16.

- Codd PJ, Venteicher AS, Agarwalla PK, Kahle KT, Jho DH (2013) Endoscopic burr hole evacuation of an acute subdural hematoma[J]. J Clin Neurosci 20(12): 1751-1753.

- Bo Du, Jianzhong X, Jintao H, Xianliang Z, Jian L et al. (2020) A Clinical Study of the Intra-Neuroendoscopic Technique for the Treatment of Subacute-Chronic and Chronic Septal Subdural Hematoma[J]. Front Neurol 10: 1408.

- Qiang C, Qiao G, Fan Z, Daofa S, Wenfei Z, et al. (2019) Evacuation of chronic and subacute subdural hematoma via transcranial neuroendoscopic approach[J]. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 15: 385-390.

- Essen T A V, Lingsma H F, Pisic D, Singh R D, Volovici V, et al. (2022) Surgery versus conservative treatment for traumatic acute subdural haematoma: a prospective, multicentre, observational, comparative effectiveness study[J]. Lancet Neurol 21(7): 620-631.

- M Ross B, Randall C, Jamshid G, Davis G, Roger H, et al. (2006) Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas[J]. Neurosurgery 58: S2-16-S2-24.

- Karibe H, Hayashi T, Hirano T, Kameyama M, Nakagawa A, et al. (2014) Surgical management of traumatic acute subdural hematoma in adults: a review[J]. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 54(11): 887-894.

- Yokosuka K, Uno M, Matsumura K, Takai H, Hagino H, et al. (2015) Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute and subacute subdural hematoma in elderly patients[J]. J Neurosurg 123(4): 1065-1069.

- Kuge A, Tsuchiya D, Watanabe S, Sato M, Kinjo T (2017) Endoscopic hematoma evacuation for acute subdural hematoma in a young patient: a case report[J]. Acute Med Surg 4(4): 451-453.

- Vega RA, Valadka AB (2017) Natural History of Acute Subdural Hematoma[J]. Neurosurg Clin N Am 28: 247-255.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.