Monochorionic Diamniotic Twin Pregnancy Associated with Molar Pregnancy: A Case Report

by Ben Rhaiem S1, Bouba S1, Veluppillai C1, Khediri Z1, Poncelet C1,2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, NOVO Hospital, 6 avenue de l’ile de france, 95300 PONTOISE, France.

2Université Sorbonne Paris Nord, UFR SMBH, 1 rue de Chablis, 93000 BOBIGNY, France.

*Corresponding author: Ben Rhaiem S,Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, NOVO Hospital, 6 avenue de l’ile de france, 95300 PONTOISE, France.

Received Date: 28 November 2024

Accepted Date: 3 December 2024

Published Date: 5 December 2024

Citation: Rhaiem BS, Bouba S, Veluppillai C, Khediri Z, Poncelet C (2024) Monochorionic Diamniotic Twin Pregnancy Associated With Molar Pregnancy: A Case Report. Gynecol Obstet Open Acc 8: 221. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-2236.100221

Abstract:

Molar pregnancies are rare events. A molar pregnancy while a twin pregnancy may be exceptional. The literature concerning potential complications, such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), intrauterine fetal death (IUFD), and/or preeclampsia, was scarce due to the very low prevalence of this condition. We report the case of a 30-year-old primiparous patient bearing a monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy, with a placenta affected by a complete hydatidiform mole. Delivery occurred by cesarean section at 31 weeks of gestational age (GA) and 1 day due to IUGR, gaving birth to a healthy offspring. Unusual elements observed during pregnancy, characteristics encountered during delivery, and postpartum evolution will be described. The diagnosis of a complete hydaditiform mole was made through histopathological analysis by a reference centre. Our case raised ethical considerations regarding management and continuation of this type of pregnancy leading to the birth of a viable offspring. This unexpected situation showed us that it was not a systematic indication for medical pregnancy termination and that there was a place for a conservative approach.

Introduction

Molar pregnancies were characterized by cystic degeneration of chorionic villi accompanied by pseudo-tumoral trophoblastic proliferation. Two main types of molar pregnancies have been described: Complete molar pregnancies, which developed without a viable embryo and with exclusively paternal genetic material, and partial molar pregnancies, where an embryo may develop with unfavourable progression due to chromosomal abnormalities. These situations were scarce, with an estimated prevalence of 1/1000 pregnancies for molar pregnancies in singleton cases [1]. This situation became even more occasional in the context of twin pregnancies, with a frequency of about 1/22,000 to 1/100,000 pregnancies [2]. In such cases, no well-established guidelines for diagnosis or management were described neither recommended, making their handling complex.

Monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancy could lead to severe complications for both the fetus and the mother. Fetal complications may include intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), and premature birth since molar pregnancies could lead to early-onset preeclampsia, malignant transformation into a choriocarcinoma, and/or persistent trophoblastic disease for the mother (PTD) [2,4]. We report a rare case of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy associated with a complete hydatidiform mole confined to the placenta, confirmed by a reference center histopathological analysis.

Keywords: twin pregnancy, molar pregnancy, intra-uterine growth retardation, placental laser, fetus papyraceous

Case Presentation

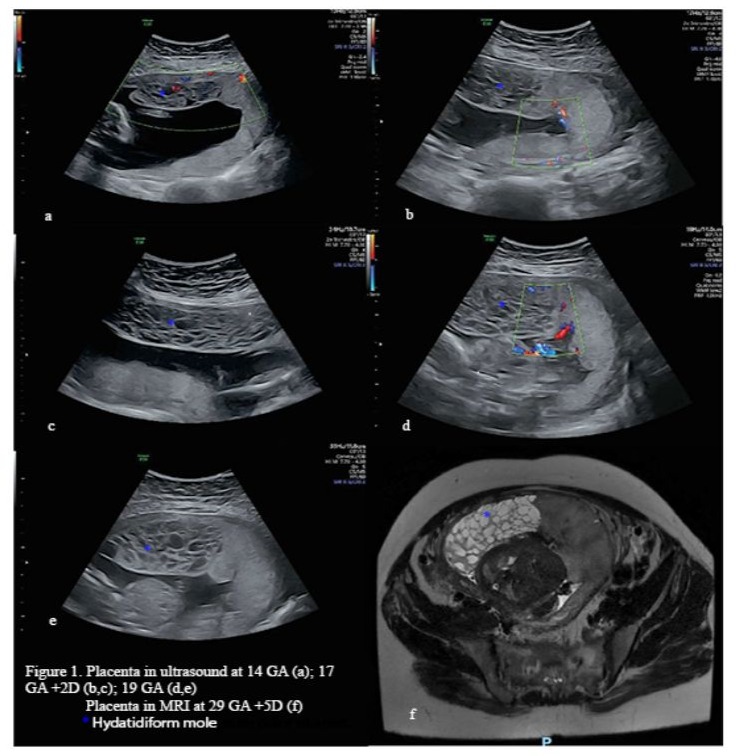

We report the case of a 30-year-old primiparous patient with no significant medical history, except for tobacco use. This pregnancy was obtained after an assisted reproductive technology (ART) process, with in vitro fertilization (IVF) and fresh transfer of two embryos, resulting in a monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy, with the loss of the second embryo. The non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT) searching chromosomal abnormalities was negative. She had only one episode of mild vaginal bleeding without consequences. The beta-HCG level at the start of pregnancy was not disproportionately high, and she did not experience severe pregnancy-related symptoms. The first-trimester ultrasound was unremarkable except for a hydropic area in the placenta. During ultrasound monitoring at 14 weeks of gestational age (GA), an abnormal appearance of the placenta was observed without a conclusive aetiology (Fig 1a). Fetus A (JA) presented with a bladder hypertrophy, significant polyhydramnios, and umbilical adiastolic flow, while fetus B (JB) had oligohydramnios, a small bladder, and normal umbilical flow. A diagnosis of grade III twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) was made. A laser coagulation treatment with amnio drainage without septsotomy was performed 24 hours later. Fetal death of JA occurred 72 hours after the intra-uterine procedure.

Starting 17 weeks and 2 GA, JB developed intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), with an estimated fetal weight of 215 grams, which was below the 1st percentile according to the Hadlock curve. The hydropic placenta appearance persisted, with numerous subcentimeter anechoic images and no Doppler flow (Fig 1b and 1c). The referral ultrasounds and the second-trimester ultrasound revealed no other abnormalities since IUGR and unusual appearance of the placenta (Fig 1d and 1e). Investigations for the IUGR, including amniocentesis, returned negative, excluding chromosomal or infectious abnormalities. Indeed, the patient showed no signs of preeclampsia.

The mother expressed the desire for pediatric management starting at 24 weeks of GA. At 23 weeks of GA and 2 days, pulmonary maturation was initiated with two injections of betamethasone. A second couple of weeks fetal monitoring regimen was established. At 26 weeks of GA, increased resistance on Doppler assessment of the umbilical artery, inversion of cerebroplacental ratio, and oligohydramnios were observed.

At 27 weeks of GA and 5 days, premature rupture of membranes was diagnosed. Hospitalization proceeded without incident on the materno-fetal side and daily monitoring of the fetal heart rate was reassuring. Ultrasound monitoring showed no Doppler abnormalities, and the fetus remained in the first percentile but continued to grow. A fetal MRI was performed at 29 weeks and 5 days of GA, which showed no abnormalities, aside from IUGR and a heterogeneous appearance of the placenta (Fig 1f).

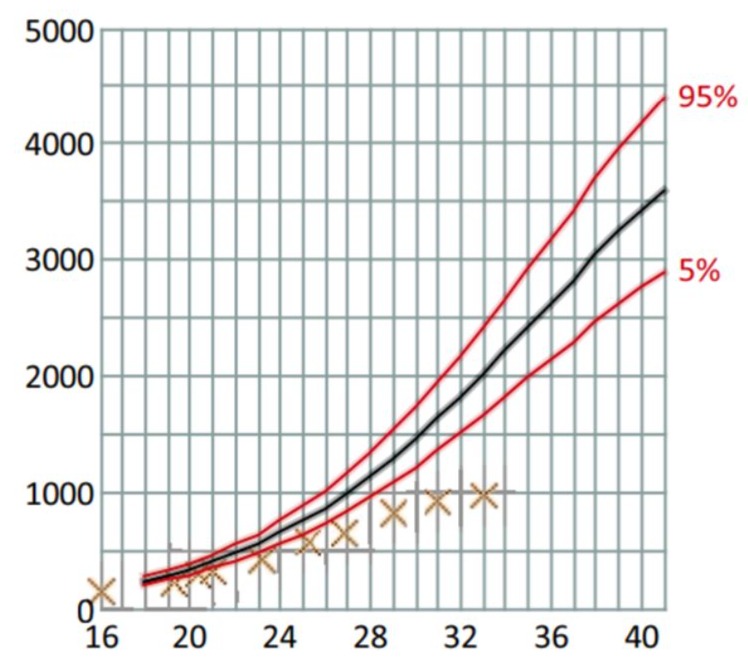

At 31 weeks GA and 1 day, the estimated fetal weight was 960 grams (less than the 1st percentile).. Doppler flows from the umbilical and cerebral arteries were considered normal. growth cessation, amnios, and prematurity scheduled birth by cesarean section after multidisciplinary session (Fig 2).

A hyprophic healthy newborn weighing 1080 grams (0.06th percentile according to AUDIPOG), Apgar score was 10/10/10 at 1/5/10 minutes, respectively, with an umbilical arterial pH of 7.34 and lactates of 1.5 mmol/L was born. Postnatal pediatric management proceeded uneventfully until discharge after simple respiratory distress.

The placenta exhibited numerous centimetre-sized vesicles, and fetus JA was integrated into the placenta as a papyraceous fetus. This placenta was fully removed from the uterine cavity without hemorrhage (Fig 3).

Due to these characteristics, the placenta was urgently sent for pathological analysis due to suspicion of a hydatidiform mole. All vesicles were removed. The remainder of the cesarean section was unremarkable (no hemorrhage during delivery, no uterine atony). After parturition, a monthly mother monitoring of serum β-hCG level was initiated. The immediate postpartum course was uncomplicated. The pathological analysis concluded that the placenta resulted from a monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy, with maternal vascular malperfusion, and suggested the appearance of a complete hydatidiform mole confined to the placenta. This suspicion was confirmed by the reference centre for French trophoblastic diseases in Lyon (France). The β-hCG level continued to decline until it became undetectable without any resurgence at 8 months after delivery.

Discussion

Scarce data were available concerning monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy giving birth to a live baby associated with complete hydatidiform mole confined to the placenta. Molar pregnancies were the result of abnormal oocyte fertilization.

One possible explanation for this situation was that during IVF, one oocyte was fertilized by a spermatozoa, and then the zygote divided to form a monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy. As for the second oocyte, it may have been fertilized by one spermatozoa and subsequently undergone endoduplication (in 80% of cases) or, more rarely, fertilized by two spermatozoa before forming a molar pregnancy [4]. Another explanation would be an intra placental complete hydatidiform mole transformation obtained from a little contingent of placental cells.

This exceptional situation often leads physicians to consider differential diagnoses during the first trimester ultrasound scan, such as an intra-placental hematoma, placental mesenchymal dysplasia, a fibroid, an iatrogenic, or infectious origin. In our case, the patient did not experience significant nausea or vomiting, reported only one episode of mild vaginal bleeding, and presented with normal β-hCG levels. No premonitory sign was available to evoke this diagnosis [4,5,6].

In our case most complications were related to monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy associated with hydatidiform mole. The monochorionic nature led to severe twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome that indicated intrauterine laser obstruction of placental vascular anastomosis with its own complications. Consequently, complete hydatidiform mole likely caused severe intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and premature rupture of membranes [2].

In cases of a twin pregnancy with both fetuses, the placenta would have had a much harder time performing its role, potentially leading to the early fetal demise of JA and JB. The placenta was able to ensure adequate growth for one fetus, resulting in IUGR for JB which makes us think that the situation could have been different if the placenta had two fetuses to vascularize.

Management of singleton pregnancies was well established and protocolized. In cases of molar pregnancy, whether complete or partial, they are generally non-evolving and present a danger to the mother due to the risk of trophoblastic gestational neoplasia progression or persistent trophoblastic disease. The standard treatment consisted of pregnancy termination even though it did not completely protect from persistent trophoblastic disease or neoplasia transformation [7]. Close follow-up was then undertaken with beta HCG level monitoring. In cases with persistent trophoblastic disease or gestational neoplasia methotrexate administration may be necessary. However, there are no clear recommendations for managing multiple pregnancies, mainly because these cases were scarce, making it difficult to conduct reliable studies. Nevertheless, the risk of persistent trophoblastic disease after a diploid mole with a coexisting fetus appears to be around 20% [8,9], and expectant management may be an interesting option [7,10].

Moreover, from an ethical perspective, it was delicate for a woman to take the risk of developing choriocarcinoma [11,12] while continuing a pregnancy that presents a high risk of complications such as intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preeclampsia, premature birth, late miscarriage, or intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) [7,8,13-15]. At the same time, terminating a desired pregnancy, especially one obtained with ART, remained an extremely difficult decision. Therefore, ethical reflection and dialogue with the patient were essential. The patient had to be fully informed of the risks and consequences of both pregnancy continuation or termination. If the decision was to continue the pregnancy, the chances of giving birth to a viable newborn were close to 43% of whom 83% will survive to 8 days of life [3,7,8].

This unexpected situation showed us that it was not a systematic indication for medical pregnancy termination and that there was a place for a conservative approach.

Conclusion

This case represented an exceptional situation of monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy associated with a hydatidiform mole. The diagnosis was made after delivery based on pathological analysis. The birth of a living child was possible. Our case highlighted the complexities of diagnosis and management, as well as the importance of thorough ethical reflection regarding molar pregnancies associated with a viable pregnancy.

Figure 1: Placenta in utrasound at 14 GA (a); 17GA +2D (b,c); 19 GA (d,e) Placenta in MRI at 29 GA +5D (f) *Hydatiform mole

Figure 2: Fetal weight estimation curve in weeks of Amenorrhea WA

Figure 3: Macroscopically heathy placenta (a), associated with a molar portion (b), and the papyraceous fetus JA (c)

References

- Savage P, Williams J, Wong SL, Short D, Casalboni S, et al. (2010) The demographics of molar pregnancies in England and Wales from 2000-2009. J Reprod Med 55: 341-5.

- Massardier J, Golfier F, Journet D, Frappart L, Zalaquett M, et al. (2009) Twin pregnancy with complete hydatidiform mole and coexistent fetus: obstetrical and oncological outcomes in a series of 14 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 143: 84-7.

- Lin LH, Maestá I, Braga A, Sun SY, Fushida K, et al. (2017) Multiple pregnancies with complete mole and coexisting normal fetus in North and South America: A retrospective multicenter cohort and literature review. Gynecologic Oncology. 1 avr 145: 88-95.

- Fisher RA, Maher GJ (2021) Genetics of gestational trophoblastic disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Juill 74: 29‑41.

- Jr L (2010) Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 203 :531-9.

- Elias KM, Berkowitz RS, Horowitz NS (2019) State‑of‑the‑Art Workup and Initial Management of Newly Diagnosed Molar Pregnancy and Postmolar Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 1 nov 17: 1396‑401.

- Hajri T, Massoud M, Vergne M, Descargues P, Allias F, et al. (2024) Multiple pregnancy with complete hydatidiform mole and coexisting normal fetus in a retrospective cohort of 141 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 230: 362 e1-362.e8.

- Sebire NJ, Foskett M, Paradinas FJ, Fisher RA, Francis RJ, et al. (2002) Outcome of twin pregnancies with complete hydatidiform mole and healthy co‑twin. Lancet. 22 juin 359: 2165‑6.

- Descargues P, Hajri T, Massardier J, Lotz JP, DevouassouxShisheboran M, et al. (2021) Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia after human chorionic gonadotropin normalization in a retrospective cohort of 7761 patients in France. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 225: 401.e1‑401.e9.

- Wee L, Jauniaux E (2005) Prenatal diagnosis and management of twin pregnancies complicated by a co-existing molar pregnancy. Prenat Diagn 25: 772-6.

- Jinno M, Ubukata Y, Hanyu I, Satou M, Yoshimura Y, et al. (1994) Hydatidiform mole with a surviving coexistent fetus following in‑vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 9: 1770‑2.

- Imafuku H, Miyahara Y, Ebina Y, Yamada H (2018) Ultrasound and MRI Findings of Twin Pregnancies with Complete Hydatidiform Mole and Coexisting Normal Fetus: Two Case Reports. Kobe J Med Sci. 28 mai 64: E1-5.

- Irani RA, Holliman K, Debbink M, Day L, Mehlhaff K, et al. (2022) Complete Molar Pregnancies with a Coexisting Fetus: Pregnancy Outcomes and Review of Literature. AJP Rep. 12: e96‑107.

- Thompson MH, Miller NR, Haugan SL, Gordon MC (2022) Case Report of a Triplet Pregnancy with Complete Hydatidiform Mole and Coexisting Twins. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2022: 2865342.

- Suksai M, Suwanrath C, Kor‑Anantakul O, Geater A, Hanprasertpong T, et al. (2017) Complete hydatidiform mole with co‑existing fetus: Predictors of live birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. mai 212: 1-8.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.