Maternal Immune Activation as a Critical Environmental Risk Factor in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

by Qi Yong1, Chao Zhao1, Lu Xia2, Tengfei Zhu3*, Kun Xia3*

1The Seventh Affiliated Hospital, University of South China, China

2 Hunan Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics, Central South University, China

3MOE Key Laboratory of Pediatric Rare Diseases, University of South China, China.

*Corresponding author: Kun Xia, MOE Key Laboratory of Pediatric Rare Diseases & Hunan Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics, University of South China, Hengyang, Hunan, 421001, China.

Received Date: September 25, 2025

Accepted Date: October 06, 2025

Published Date: October 08, 2025

Citation: Yong Q, Zhao C, Xia L, Zhu T, Xia K, et al. (2025) Maternal Immune Activation as a Critical Environmental Risk Factor in Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. J Neurol Exp Neural Sci 7: 163. https://doi.org/10.29011/2577-1442.100063

Abstract

Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) represent chronic cerebral dysfunctions arising from gene-environment interactions, encompassing conditions such Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADHD). Emerging evidence identifies Maternal immune activation (MIA) as a critical environmental risk factor for NDDs. Gestational infections, inflammatory responses, or immune dysregulation elevate maternal-fetal inflammatory mediators, which disrupt neurodevelopmental trajectories via placental-fetal signaling cascades. Preclinical models (rodents, non-human primates) demonstrate that MIA induces characteristic NDD phenotypes-including social deficits and cognitive impairments-through microglial hyperactivation, aberrant synaptic pruning, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Concurrently, gut microbiota dysbiosis and Th17/Treg immune imbalance exacerbate neuroinflammatory processes. Novel therapeutic strategies targeting inflammatory pathways microglial modulation, or microbial homeostasis restoration show translational promise. Future investigations must unravel MIA's molecular underpinnings and multifactorial interactions to enable early-risk stratification and precision interventions for NDDs.

Introduction

NDDs are chronic brain dysfunction syndromes arising from multifactorial genetic or acquired etiologies that impair pluripotent cerebral domains, including cognition, motor function, social adaptability, and behavioral regulation. Representative NDD subtypes encompass ASD, ADHD, intellectual disability (ID), and schizophrenia (SCZ). Large-scale twin studies estimate heritability at 0.6–0.9 for ASD and 0.76 for ADHD [1-3], with significant genetic overlap observed between ADHD and ASD. Genetic contributions account for approximately 50% of idiopathic ID cases, escalating to ≥66% in moderate-to-severe presentations. However, NDD pathogenesis reflects dynamic interplay between polygenic susceptibility and environmental exposures, with nongenetic factors demonstrating substantial etiological weight. This is evidenced by the discordance rates in ASD and SCZ twin cohorts, underscoring environmental triggers’ critical role in neurodevelopmental trajectory disruption [4].

MIA has been increasingly recognized as a critical risk factor for ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders. MIA arises from gestational immune hyperactivation triggered by maternal infections, autoinflammatory conditions, or autoimmune diseases, encompassing but not limited to infection-induced inflammatory dysregulation [5]. Notably, MIA can be initiated by both infectious stimuli (e.g., viral/bacterial pathogens) and sterile triggers, including maternal asthma, obesity, and autoimmune disorders. Gestational immune perturbations exert enduring consequences, with MIA inducing persistent remodeling of developing neural circuits and altering fetal brain developmental trajectories [6]. When superimposed on genetic and environmental vulnerabilities, this immune dysregulation amplifies offspring risks for NDDs [7,8], including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, ADHD, cerebral palsy, developmental delay, cognitive dysfunction, anxiety/ depression, and ASD [9].High-resolution ex vivo MRI and electron microscopy analyses in murine models reveal that late-gestation MIA exposure induces volumetric expansion in embryonic brain regions-specifically the striatum/caudoputamen, hippocampus, lateral septum, cingulate cortex, and cerebellum [10]. These neuroanatomical anomalies mirror structural abnormalities identified in neuroimaging studies of ASD and schizophrenia patient [11]. Furthermore,third-trimester MIA exacerbates neuroinflammation and compromises placental efficiency in prenatal rat models, as evidenced by elevated proinflammatory cytokines and impaired nutrient transport mechanisms [12].

Mechanistic and Translational Perspectives: This review systematically delineates the multi-tiered mechanisms underlying MIA-induced NDDs, encompassing:Maternal-fetal interface cytokine cascades (IL-17A/IL-6/TNF-α axis) disrupting neural progenitor cell differentiation;Microglia-driven synaptic pathology via aberrant pruning and oxidative stress-mediated damage;Gutbrain axis dysregulation coupled with Th17/Treg immune polarization amplifying neuroinflammatory cascades;Translational immunomodulatory strategies targeting IL-17A blockade, microbiota transplantation, and neuroprotective interventions.

We further evaluate the therapeutic potential of these mechanisms in reshaping developmental trajectories, establishing a conceptual framework for preemptive NDD interception during critical neurodevelopmental windows.

MIA and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Epidemiological Evidence Linking MIA to Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The association between environmental factors, MIA, and NDDs is well-established. Epidemiological studies demonstrate significant correlations between gestational infections and elevated risks of SCZ, ASD, and epilepsy in offspring. Historical cohort analyses reveal marked increases in schizophrenia and ASD incidence following the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic and 1964 rubella epidemic [13,14]. Second-trimester influenza infection confers a 2- to 8-fold increased schizophrenia risk [15], while prenatal exposure to Toxoplasma gondii [16], herpes simplex virus type 217, and urinary/respiratory infections [18-21] similarly elevates neuropsychiatric vulnerability.

Notably, the California Department of Developmental Services documented a “winter birth phenomenon,” wherein infants conceived during winter months exhibit heightened ASD susceptibility22. A 1990–2002 pediatric cohort study suggests this seasonal risk may correlate with increased respiratory infections in colder months [22]. A Danish nationwide study of 1.6 million children further confirmed that hospitalization-requiring maternal infections or inflammation significantly elevates offspring psychiatric risks, underscoring MIA’s pathogen-agnostic immunopathic effects.

Beyond infections, maternal autoimmune conditions (e.g., asthma, allergies), acute stress, environmental pollutants, and nutritional imbalances amplify ASD risk through immune hyperactivation [23-25]. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified concerns regarding prenatal viral impacts, with SARS-CoV-2 infection linked to fetal growth restriction and neurodevelopmental sequelae [26]. Globalization-driven resurgent infections and autoimmune disease proliferation may synergistically fuel the NDD pandemic, necessitating urgent dissection of MIA-specific immune pathways and gene-environment interplay to inform early intervention strategies.

Experimental Animal Evidence of MIA

Mounting evidence from animal models has robustly validated neurodevelopmental abnormalities induced by MIA [27]. Experimental paradigms typically involve artificial immune system activation during gestation to assess offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes. Widely used MIA induction methods include exposure to human influenza virus, viral mimetic polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), localized inflammatory agents (e.g., turpentine), or specific proinflammatory cytokines7, [28].Amodeo et al. demonstrated that gestational Poly(I:C) exposure impairs offspring learning and social interaction capabilities, inducing autism- and schizophrenialike behavioral phenotypes. These effects correlate with persistent disruptions in glutamatergic neurotransmission, mTOR signaling, and potassium channel activity [29]. In murine models, O’Loughlin et al. observed upregulated amygdalar proinflammatory cytokine expression alongside chronic microglial activation and astrogliosis following intraperitoneal LPS administration during pregnancy [30]. Rat studies by Fortunato et al. revealed that LPS-induced MIA elevates stereotyped repetitive behaviors and reduces social engagement in offspring-phenotypes reversible through ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intervention [31].

Complementing rodent studies, non-human primate (NHP) models-with closer physiological parallels to human pregnancyare increasingly employed in MIA research [32]. Seminal work by Bauman et al. in rhesus macaques demonstrated that mid-gestation Poly(I:C) exposure exacerbates abnormal behaviors (e.g., tremors, tail clasping, self-clasping) during weaning, with adults exhibiting heightened stereotypies and impaired social reciprocity [33].

Inflammatory Mediators in MIA-Induced Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities

The developing brain exhibits heightened sensitivity to environmental signals, with MIA -driven cytokine cascades and inflammatory responses serving as pivotal disruptors of fetal neurodevelopment. Gilmore and Jarskog first proposed in 1997 that inflammatory mediators might underlie infectionassociated fetal brain developmental disruptions [34], a hypothesis now substantiated by extensive epidemiological studies and experimental MIA models delineating cytokine network dysregulation as central to MIA pathophysiology.

Prenatal inflammatory exposure triggers maternal-fetal upregulation of cytokines and chemokines-including interferongamma (IFN-γ), IFN-β, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukins (IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and C-reactive protein (CRP)-that induce fetal endogenous cytokine production, thereby altering cerebral ontogeny [35-37]. Maternal-fetal cytokine profiling demonstrates MIA-induced dysregulation critically contributes to ASD pathogenesis. Analysis of 60 inflammatory mediators and growth factors in mid-pregnancy maternal serum and umbilical cord blood from the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) identified TNF-α, Serpin E1, VCAM1, and IL-1β as key predictors of neurodevelopmental trajectories and ASD diagnosis [37].

A longitudinal birth cohort study on ADHD revealed that elevated umbilical cord blood IL-6 and TNF-α levels-when integrated with polygenic risk scores-predicted increased ADHD symptom severity in 8- to 9-year-olds via structural equation modeling, implicating perinatal inflammation in ADHD pathogenesis through early neural circuit modulation [38]. Similarly, fetal exposure to IL-8 shows significant schizophrenia risk association [39]. Herein, we comprehensively review the mechanistic roles of key inflammatory mediators in MIA-induced neurodevelopmental perturbations.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

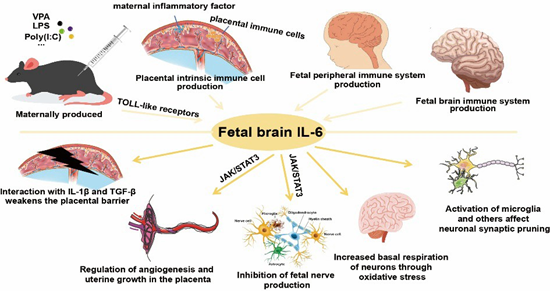

Dysregulated IL-6 levels critically disrupt fetal brain development, driving neurobehavioral abnormalities in MIA-exposed offspring [40] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: IL-6 in MIA.

Under physiological conditions, IL-6 remains minimally detectable in the brain, but its production escalates during pathological states. Severe peripheral or central inflammatory challenges-such as bacterial meningitis-trigger IL-6 accumulation in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [41]. Elevated IL-6 levels are observed in the prefrontal cortex, CSF, and cerebellum of autistic children. In MIA models, maternal serum IL-6 peaks 3 hours post-challenge before returning to baseline within 24 hours [42]. Strikingly, recombinant IL-6 administration alone induces prepulse inhibition (PPI) deficits and ASD/schizophrenia-like behaviors in adult offspring [43,44]. Conversely, IL-6 antibody-treated or IL-6 knockout dams fail to transmit behavioral or transcriptional anomalies to progeny following immune challenge40. IL-6 has further emerged as a prognostic biomarker for neuropsychiatric disorders including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ASD [45].In rodent MIA models, maternal IL-6 activates placental decidual immune cells, stimulating localized IL-6

production [46]. This placental IL-6 signaling initiates pathogenic cascades by:Downregulating placental growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)-critical neurodevelopmental regulators linked to ASD;Inducing cerebellum-specific Purkinje cell deficits in lobule VII;Driving neuronal loss and behavioral impairments reversible via IL-6 receptor α (IL6Rα) blockade40.Mechanistically, maternal IL-6 traverses the placental barrier during mid-late gestation, directly stimulating fetal IL-6 synthesis and establishing feedforward inflammatory loops [47,48]. It synergizes with IL-1β and TGF-β to disrupt chorionic tight junctions (TJ), compromising placental integrity [49]. Placental JAK/STAT3 pathway activation-particularly in spongiotrophoblasts-upregulates proinflammatory genes while altering neurodevelopmental factor secretion [50]. IL-6/JAK2/ STAT3 signaling further suppresses neurogenesis via DNMT1/ TET3-mediated epigenetic remodeling, with JAK2 inhibition rescuing hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive deficits in APP/ PS mice [51]. In cortical neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), exposure to interleukin-6 (IL-6) resulted in upregulated gene expression within the chemokine signaling pathway and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway categories. Concurrently, IL-6-induced oxidative stress elevated basal respiration, ATP production, and non-mitochondrial respiration in differentiated neurons, suggesting a marked increase in metabolic activity and energy demand [52].Notably, HyperIL-6 treatment of dorsal forebrain organoids (DFOs) recapitulates MIA’s early corticogenic effects [53], activating JAK/STAT cascades and inducing transcriptional shifts mirroring human neurodevelopmental perturbations [54].

Interleukin-17A

Interleukin-17A (IL-17A), a proinflammatory cytokine predominantly expressed by TH17 cells [55], plays pivotal roles in autoimmune disorders, inflammatory responses, tumorigenesis, and host defense against bacterial and fungal infections. Notably, IL-17A critically regulates neural function during cortical development and modulates neuroinflammatory processes. Genome-wide copy number variation (CNV) analysis in ASD patients identified IL-17A as one of the enriched genes [56]. Elevated IL-17A levels were observed in the serum of children with ASD and in neutrophils isolated from ASD patients [57,58], with its concentration positively correlating with autism severity57. These alterations were accompanied by upregulated phosphorylated nuclear factor-κB (p-NF-κB), IL-6, and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2)/reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling. Murine studies confirmed that increased maternal IL-17A levels in MIA models induce elevated IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) expression in fetal brains, establishing IL-17A as a key pathogenic factor in ASD.IL-17A is primarily secreted by TH17 cells, and IL-6 serves as a critical factor for TH17 cell differentiation. Elevated IL-6 levels in the placenta or fetal brain following MIA may drive IL-17A upregulation. This upregulation further stimulates the production of multiple cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), granulocyte-macrophage colonystimulating factor (GM-CSF), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). MIA induces aberrant expression of cortical layer-specific marker genes, including SATB2, TBR1, and CTIP2, in the cortical cells of offspring mice. However, offspring from MIA dams pretreated with IL-17A-blocking antibodies exhibit normal expression of these markers [59]. In miR-301a knockdown mice, suppression of the SOCS3/STAT3 pathway and subsequent reduction in downstream cytokines IL-6 and IL-17A significantly ameliorate poly(I:C)-induced ASD-like behaviors, including deficits in social interaction and anxiety-related behaviors [60].

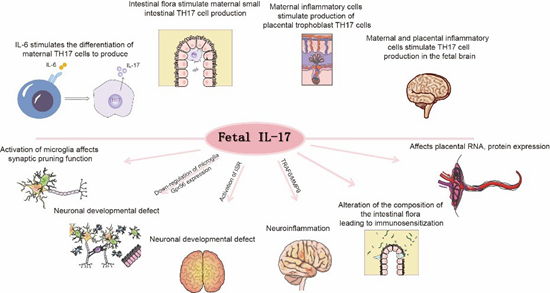

IL-17A signaling influences fetal brain development through multiple mechanisms (Figure 2).

Figure 2: IL-17A in MIA.

Maternal IL-17A accumulates in the placenta and directly crosses the placental barrier to impact fetal development [61]. Concurrently, maternal IL-17A enhances IL-17 receptor (IL17R) expression at both mRNA and protein levels in placental trophoblasts, amplifying signal transduction [62]. Elevated IL17A does not alter placental permeability but binds to placental IL17RA receptors and traverses the placenta [61]. Evidence indicates that MIA downregulates microglial Gpr56 expression in fetal brains in an IL-17A-dependent manner, leading to parvalbuminpositive (PV+) interneuron deficits and autism-like behavioral phenotypes in offspring [63]. Placental IL-17A signaling modulates fetal brain microglia; IL-17A administration activates microglia, enhancing their phagocytic activity without increasing cellular density [64].Moreover, integrated stress response (ISR) activation in MIA offspring is IL-17A-dependent and necessary for the emergence of core behavioral phenotypes. Genetic knockdown of ISR components alleviates ASD-like phenotypes in male MIA offspring, revealing a novel mechanism by which IL-17A mediates MIA effects [65]. Additionally, the TRAF6/MMP9 pathway under IL-17A signaling is implicated in ASD pathophysiology. Modulation of the IL-17A/TRAF6/MMP9 axis ameliorates MIAinduced ASD-like behaviors in adulthood [66]. As a gut barrier cytokine, IL-17A is critical for maintaining intestinal microbiota homeostasis. MIA exacerbates IL-17A-driven immune responses, altering gut microbial composition and inducing immune sensitization in offspring, thereby increasing susceptibility to bacterial infection-triggered intestinal inflammation [67].

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β)

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is one of the key cytokines elevated in

ASD [68]. In MIA models mimicking viral infection, fetal brain IL-1β levels peaked 24 hours post-injection and continued to rise, exhibiting the highest concentration among cytokines analyzed [69]. Offspring of LPS-exposed MIA dams also showed increased IL-1β mRNA levels in fetal brains70. Multiple studies confirm that viral mimetics significantly elevate fetal brain IL-1β expression for at least 24 hours post-MIA induction [69]. The association between ASD pathogenesis and IL-1 signaling, including its receptor family, has been experimentally validated [71], with IL-1β gene polymorphisms being more prevalent in children with ASD [72,73]. Disrupted IL-1β signaling during early development leads to synaptic homeostasis dysregulation and ASD-like behavioral deficits [73], as neuronal function critically depends on tightly regulated IL-1β levels [74]. IL-1β likely mediates MIA effects through microglial modulation: IL-1 receptor type 1 (IL-1R1) deficiency reduces microglial synaptic phagocytosis, while IL1R1 antagonism in wild-type microglia similarly impairs synaptic engulfment capacity [73]. Furthermore, IL-1β selectively enhances downstream mTOR pathway activity, influencing synaptic pruning and phagocytosis. Dysregulated IL-1β expression is implicated in the etiology of multiple neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders [73]. Maternal inflammation during pregnancy can indirectly damage placental integrity via IL-1 signaling, resulting in fetal mortality, abnormal brain development, or offspring neuropathology. Notably, IL-1 receptor antagonist administration effectively rescues maternal inflammation-induced placental and neurodevelopmental defects12.

TNF-α and IFNs

In MIA models, male offspring of dams exhibit anxiety-like and obsessive-compulsive behavioral deficits, which correlate with reduced hypothalamic concentrations of granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF), interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-7 (IL-7), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) [75]. Among these cytokines, TNF-α-primarily released by macrophages and microglia-modulates brain development and function [76,77]. Late-gestation immune challenges specifically activate IL-10 and TNF-α responses in fetal brains, which are linked to increased postnatal apoptosis [78]. Furthermore, offspringderived TNF-α may impair fetal development by suppressing MAP2+ dendritic growth. In a human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived neuron-macrophage co-culture system, MAP2+ dendritic growth was inhibited by TNF-α and IL-1α secreted by GM-CSF-primed macrophages (GM-CSFMΦ), with this suppression being more pronounced in GM-CSFMΦ from ASD individuals compared to typically developing (TD) controls [79]. Inflammation also induces microglial activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of offspring mice, triggering proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α and TNF-α. This leads to dendritic shortening, reduced branching, and subsequent social avoidance behaviors [80,81].

In murine and zebrafish models, type I interferons (IFN-I) promote microglial phagocytosis of neurons during cortical developmental remodeling, thereby limiting the accumulation of DNA-damaged neurons [82]. Within MIA mechanisms affecting fetal brain development, IFN-γ may regulate synaptic refinement. This immunomodulatory cytokine induces prolonged synaptic modifications to modulate synaptic activity while disrupting glutamate receptor clustering on dendrites [83]. Cortical neurons differentiated from iPSCs and exposed to IFN-γ during differentiation exhibit aberrant neurite outgrowth and altered dendritic spine density [52].

Given the association between MIA and diverse neurodevelopmental disorders, developing interventions targeting inflammatory mediators is critical. For instance, blocking specific cytokines (e.g., IL-17A) or their signaling pathways may effectively mitigate MIA-induced adverse effects on fetal neurodevelopment.

MIA-Associated Cellular Mechanisms in Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities

Peripheral Immune Cells

Aberrant T cell activation is closely linked to neurodevelopmental disorders. CD4+ T cell dysregulation has been observed in children with ASD, characterized by an elevated proportion of Th17 cells and reduced regulatory T cells (Tregs) [84,85]. The Th17/Treg ratio exhibits a significant positive correlation with ASD severity, while Treg abundance inversely correlates with symptom severity [86].

Using MIA animal models, Choi et al. demonstrated that maternal CD4+ T cells expressing RORγt are essential for the emergence of ASD-like phenotypes in offspring. In poly(I:C)-induced MIA offspring, CD4+ T cells exhibit enhanced differentiation into Th17 cells upon stimulation [87-89], constitutive upregulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression [89], and systemic Treg deficiencies. Elevated CD4+ T cell reactivity in the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes further reflects compromised immune homeostasis in MIA offspring [90]. Bioinformatic and experimental analyses revealed that activation of the PI3K/Akt/ NF-κB pathway in offspring upregulates STAT3 signaling, driving Treg/Th17 imbalance [91]. Similarly, in MIA models induced by Toxoplasma gondii infection, no significant differences in T or B cell percentages were observed in offspring at 2 or 4 weeks of age. However, granulocyte counts nearly doubled by 4 weeks, and TH1/TH17 subsets expanded dramatically in T cells by 10– 12 weeks, accompanied by declining Treg and TH2 populations. This T cell dysregulation exhibited time-dependent exacerbation [92], representing a major contributor to neurodevelopmental impairments. Intravenous administration of purified Tregs to MIA offspring ameliorates Th1/Th17 skewing [93] and reverses behavioral deficits. Notably, Tregs isolated from MIA dams can remodel inflammatory microenvironments in offspring brains 92. Parasite-specific T lymphocytes release high interferongamma (IFN-γ) levels, promoting Th1 effector differentiation and macrophage activation-critical for antimicrobial functions such as nitric oxide release [94].

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a widely used MIA inducer, paradoxically increases natural regulatory CD4+Foxp3+ T cell numbers and proportions in offspring by weeks 8–10. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis identified upregulation of 18 proteins in LPS-treated CD4+ T cells, 13 of which are metabolismassociated [95]. LPS-induced MIA also shifts offspring immune development toward Th1-biased responses, disrupting Th1/Th2 balance. Additionally, offspring T cells display impaired IL10 secretion in vitro, indicating MIA-induced dysregulation of immunomodulatory cytokine production [96]. In SARS-CoV-2associated MIA offspring, CD14+ monocytes exhibit upregulated interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) expression, downregulated IFNAR2, and elevated TLR transcripts (TLR2, TLR4, TLR5) alongside increased FOS and reduced NF-κB inhibitor levels. These changes likely reflect prenatal IFN exposure. Fetal bone marrow CD14+ monocytes also show reduced antigen-presenting capacity and transcriptional signatures of B cell dysfunction [97].

Beyond offspring alterations, maternal T cells critically mediate intergenerational effects. Maternal antibodies and immune cells can cross the placenta to influence fetal brain development. Postpoly(I:C) administration, MIA dams exhibit pronounced M1 macrophage polarization (placenta, spleen, peritoneum) with concomitant M2 reduction. Macrophages are essential for MIAinduced placental maldevelopment and inflammation. Depleting maternal macrophages via chlorophosphate liposomes (CL) rescues anxiety-like phenotypes and autism-associated behaviors in adult offspring [98]. Helminth-derived Sjp90α protein induces Treg production of IL-10, modulating macrophage activity [99]. MIA rapidly elevates maternal plasma IL-17A levels within 12–24 hours post-poly(I:C) injection at E12.5. Pre-existing Th17 cellsnot de novo differentiated populations-constitute the primary IL17A source in inflamed pregnant mice [100].

Microglia

Microglia, a critical component of the central nervous system (CNS) glial population, play pivotal roles in CNS development and homeostasis maintenance [101]. These cells sense neuronal activity and regulate neurodevelopment through the release of immunomodulatory factors, including phagocytosis of neural progenitor cells, guidance of dopaminergic axon extension, neuronal positioning [102], structural integrity maintenance, and selective synaptic pruning103-105. Microglia can polarize into M1 or M2 phenotypes [106]. The M1 phenotype produces pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β) and chemokines, exerting pathogen clearance and tissue repair functions, yet excessive inflammatory mediator release may impair neuronal function. Conversely, the M2 phenotype secretes anti-inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β) to promote tissue repair and neuroprotection.

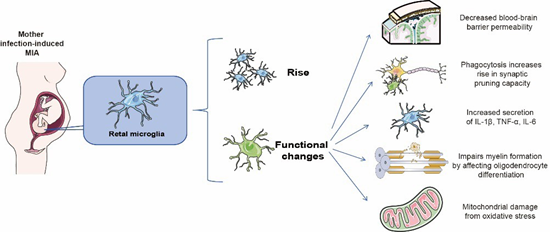

Microglial priming-a major consequence of MIA-serves as a key mechanism underlying age-dependent neuronal dysfunction and behavioral phenotypes in offspring (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Microglia in MIA.

Distinct MIA induction methods differentially alter microglial phenotypes in postnatal and adult offspring brains [107]. For instance, prenatal valproic acid (VPA) exposure increases microglial soma size, while prenatal LPS exposure enhances hippocampal microglial activation in MIA offspring [108]. MIA also induces microglial hyperplasia in brain regions like the hippocampus (HPC). Although MIA does not alter microglial morphology, its timing may subtly influence postnatal microglial differentiation109. Activated microglia in MIA exhibit functional alterations, including upregulated inflammatory mediator gene expression, enhanced proliferation, phagocytic activity, and release of cytotoxic cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [110,111], collectively disrupting fetal brain development10.

During development, microglia regulate neural progenitor cell (NPC) pool size by stimulating NPC proliferation112 and subsequently phagocytosing excess NPCs113. MIA disrupts these microglia-mediated neurodevelopmental processes [102,114,115]. CX3CR1 deficiency impairs microglial signaling and function by altering developmental trajectories [116]. LPS- or poly(I:C)induced MIA perturbs microglia-neuron communication in young male offspring via CX3CL1-CX3CR1 and/or CD200-CD200R signaling dysregulation, contributing to neurodevelopmental deficits [117]. LPS-MIA offspring show reduced CX3CR1 mRNA expression at postnatal day 15118. Beyond providing neurotrophic support (e.g., insulin-like growth factor-1) [119,120], microglia dynamically remodel synapses through phagocytosis and trogocytosis103, modulating synaptic plasticity and strength via activity-dependent interactions [121]. MIA exacerbates microglial synaptic pruning and phagocytosis10, with dysfunctional phagocytosis implicated in ASD and schizophrenia (SCZ). Excessive NPC phagocytosis and defective synaptic pruning disrupt neuronal connectivity and brain circuitry [122]. Altered microglial homeostasis impedes NPC self-renewal/differentiation, predisposing to autism-like behaviors [123]. Microglia may regulate MIA-induced interneuron deficits via G proteincoupled receptor 56 (GPR56) 63. Aberrant microglial synaptic elimination and autophagy underlie MIA-associated circuit phenotypes [124]; mTOR inhibitor rapamycin rescues dendritic pruning defects and ASD-like behaviors in Tsc2+/- mice [125], while activating microglial autophagy ameliorates SCZ-related abnormalities in MIA offspring [126]. Activated microglia release excess ROS [111], damaging mitochondria. Microglia immune receptors can specifically recognize mitochondrial componentssuch as mitochondrial DNA, transcription factor A (TFAM), and cardiolipin-released during mitochondrial dysfunction. This recognition activates pro-inflammatory processes and triggers mitochondrion-dependent inflammation [127], subsequently inducing intracellular cascades that regulate mitochondrial metabolism and function [128] Microglia can help restore bloodbrain barrier (BBB) permeability by limiting the penetration of peripheral factors into the CNS parenchyma. On the other hand, activated microglia increase BBB permeability and vascular leakage through the release of cytokines or reactive oxygen species, adversely affecting BBB integrity [129,130]. Chronic MIA-induced inflammation promotes microglial phagocytosis of astrocytic end-feet, further compromising the BBB [131].

Contrary to the prevailing view of microglial hyperactivation postMIA, Akira Sawa et al propose that prenatal stress induces longterm microglial hyporesponsiveness. In MIA offspring, microglia exhibit sustained immune hypoactivation across development, accompanied by chromatin remodeling, altered transcription factor occupancy, and dysregulated gene expression-factors increasing schizophrenia risk. These “primed” microglia underlie ventral striatal circuit dysfunction, which prenatal microglial replacement can rescue alongside IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6 normalization [132]. MIA-induced microglial alterations represent a pathophysiological bridge linking maternal inflammation to neurodevelopmental disorder (NDD) risk, positioning microglia as novel therapeutic targets. Future research should dissect interactions among diverse cell types (T cells, microglia, astrocytes, neural stem cells) in MIA mechanisms and their collective impact on neurodevelopment.

Potential Mechanism of MIA-Induced Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis

The gut microbiota serves as a critical modulator of core symptoms in various neurological disorders133, exerting profound effects on the central nervous system (CNS). The gutbrain axis-a bidirectional communication network involving neurons, hormones, immune cells, and microbial metabolitesmediates intimate crosstalk between the gut and brain [134,135]. Through this axis, gut microbes regulate host behaviors associated with neurodevelopmental dysfunction [136].MIA compromises intestinal integrity. Offspring from poly(I:C)-induced MIA dams exhibit reduced expression of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a scaffold protein critical for tight junction (TJ) stabilization, in adult small and large intestines. Bacteroides fragilis supplementation restores intestinal permeability and upregulates genes governing gut barrier integrity in MIA offspring [137], while also promoting stem cell regeneration and enhancing mucus secretion [138]. MIA alters maternal gut microbiota composition and function, inducing dysbiosis that may impact maternal-fetal health through multiple pathways. Prenatal valproic acid (VPA) exposure induces ASDlike behaviors in offspring [139], accompanied by gut microbial compositional shifts. Lactobacillus reuteri treatment rescues social deficits in ASD mice via vagus nerve-dependent mechanisms, restoring social interaction-induced synaptic plasticity in the ventral tegmental area [135].

Elevated IL-17A levels during MIA are influenced by maternal gut microbiota. The presence of segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) in the maternal microbiome drives increased maternal serum IL17A. In SFB-deficient dams, even under immune challenge, IL17A remains unchanged, and offspring behavioral abnormalities are absent140. Preemptive eradication of vancomycin-sensitive SFB prior to MIA induction prevents offspring behavioral deficits [140]. Accumulating evidence highlights the maternal and offspring microbiomes as key regulators of microglial development, homeostasis, and MIA-associated behavioral outcomes. Adult germ-free mice or those with microbiota complexity limitations exhibit global microglial defects and impaired innate immune responses [141]. Prenatally, maternal Lactobacillus murinus deficiency disrupts embryonic microglial transcriptomes, alters brain microglial colonization (e.g., increased density and hyperramification), and elevates chromatin accessibility [142,143]. Microbiota-targeted interventions in MIA offspring partially ameliorate gut alterations, stereotyped behaviors, anxiety-like phenotypes, and sensorimotor gating deficits [144].

While the gut microbiome modulates neurological outcomes via the microbiota-gut-brain axis, mechanisms underlying microbial rescue of neuronal dysfunction remain incompletely understood. Clinical interventions targeting gut microbiota to ameliorate neurobehavioral disorders represent a promising frontier.

Alterations in Synaptogenesis and Pruning

Synaptogenesis and synaptic pruning are critical processes during brain development, governing the formation of new synaptic connections and the refinement of neuronal networks. Impairments in synaptic structure and function are central to neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

MIA disrupts synaptic development, maturation, and pruning through multiple pathways, including inflammatory cytokinemediated interference with signaling cascades and microglial activation. Maternal inflammatory signals traverse the placental barrier, perturbing neurodevelopmental pathways in offspring. For instance, IL-6 inhibits neurogenesis via JAK2/STAT3 signaling51 ,while offspring-derived TNF-α suppresses MAP2+ dendritic growth, impairing synaptic development79. Poly(I:C)induced MIA significantly reduces expression of presynaptic (e.g., synaptophysin) and postsynaptic (e.g., PSD95) proteins in offspring hippocampi, compromising basal synaptic transmission (field potential [FV] and excitatory postsynaptic potential [fEPSP]) and plasticity (paired-pulse facilitation [PPF] and longterm potentiation [LTP]) [145]. Additionally, MIA downregulates Shank3 expression, disrupting neuronal connectivity, synaptogenesis, and dendritic spine maturation.

Beyond synaptogenesis, aberrant synaptic pruning profoundly impacts neurodevelopment 146. In male offspring of LPS-induced MIA dams, dendritic density in dentate gyrus granule cells remains elevated during peak pruning stages (postnatal day 15) [118], a phenotype linked to persistent network hyperconnectivity and ASD-like behaviors147. IL-17A signaling enhances microglial phagocytic activity in fetal brains 64, while poly(I:C)-exposed MIA offspring exhibit upregulated hippocampal IL-1β expression in adulthood [118]. IL-1β selectively amplifies mTOR pathway activity, further dysregulating synaptic pruning and phagocytosis [73].

MIA disrupts fetal synaptogenesis and pruning primarily via microglial activation. Targeted interventions to modulate these pathways may mitigate long-term neurodevelopmental risks in offspring.

Other Mechanisms

MIA induces neurodevelopmental disorders through multiple mechanisms, including interference with critical signaling pathways, disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), placental dysfunction, and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis. The crosstalk between inflammatory and neurodevelopmental signaling pathways constitutes a complex regulatory network. MIA disrupts fetal neurodevelopmental processes by impairing key pathways such as Notch [148], NFκB91, and JAK/STAT [149], which modulate the expression of neurodevelopmental genes (e.g., BDNF, GSK-3β, and components of Notch/Wnt pathways). These perturbations inhibit neural stem cell proliferation/differentiation and neuronal migration/ synaptogenesis, ultimately altering cortical circuit architecture and function [150].

Notably, MIA increases BBB permeability, compromising its structural integrity and allowing immune cells, cytokines, and neurotoxic molecules to infiltrate the brain parenchyma, thereby amplifying neuroinflammation The placenta serves as a physical and immunological interface during MIA. Animal studies demonstrate that maternal inflammation transmits to the fetus via both direct (e.g., altered mRNA expression of placental amino acid transporters like leucine transporters) and indirect mechanisms, disrupting fetal brain growth trajectories [151].

Mechanistically, MIA dysregulates the neuroendocrine system through HPA axis hyperactivation-a hallmark of ADHD pathophysiology. Chronic stress-induced HPA dysfunction elevates corticotropin and cortisol levels, which Promote catabolic states via lipolysis/gluconeogenesis.Inhibit neuronal growth and dendritic arborization;Impair synaptic plasticity and neurocognitive functions.This endocrine-metabolic cascade exacerbates both ADHD symptoms and metabolic disturbances 38.

Summary and Perspectives

Accumulating evidence underscores the pivotal role of MIA in neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). However, MIA lacks standardized diagnostic criteria and is broadly defined as prenatal exposure to infection, aberrant inflammation, or immune dysregulation. The interplay of environmental, genetic, and immunological factors complicates precise mechanistic delineation. While animal models and epidemiological studies have established cytokine-driven immune responses as central to MIA-induced neuropathology, the developmental mechanisms underlying human MIA-associated NDD phenotypes remain incompletely resolved.

Successful MIA modeling holds translational potential for developing therapeutic or preventive strategies against NDDs. Leveraging diverse MIA models enables dynamic tracking of disease progression and symptom-specific biomarker quantification, facilitating early identification of high-risk populations. A deeper understanding of MIA mechanismsparticularly immune-neuroinflammatory crosstalk-will inform targeted interventions. Strategies modulating immune pathways (e.g., cytokine blockade, microglial reprogramming) represent promising therapeutic avenues, warranting validation in preclinical models. Future research should prioritize:Mechanistic Precision: Deciphering synergistic interactions between genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and immune dysregulation. Biomarker Discovery: Identifying quantifiable immune or neurodevelopmental signatures for early diagnosis.Therapeutic Innovation: Developing immunomodulatory agents with bloodbrain barrier permeability and temporal specificity.

Translational Integration: Bridging preclinical findings to human cohorts through longitudinal multi-omics approaches.

By addressing these challenges, MIA research may catalyze paradigm shifts in NDD prevention and treatment, ultimately mitigating the global burden of neurodevelopmental impairments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Research on application of brain organoids in neurodevelopmental disorders in Kun Xia lab is supported by MOE Key laboratory of Rare Pediatric Diseases; National Natural Science Foundation of China (82130043, 82330035 and 82361138573 to K.X., 82471198 to L.X.).

Reference

- Schaffer LS, Breunig S, Lawrence JM, Foote IF, Grotzinger AD, et al. (2024) Characterizing genetic pathways unique to autism spectrum disorder at multiple levels of biological analysis. Molecular Autism 15(1): 46.

- Tick B, Bolton P, Happé F, Rutter M, Rijsdijk F, et al. (2016) Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of twin studies. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines 57(5): 58595.

- Bai D, Yip BHK, Windham GC, Sourander A, Francis R, et al. (2019) Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort. JAMA psychiatry 76(10): 1035-1043.

- Minakova E, Warner BB (2018) Maternal immune activation, central nervous system development and behavioral phenotypes. Birth defects research 110(20): 1539-1550.

- Brown AS, Derkits EJ (2010) Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. The American journal of psychiatry 167(3): 261-80.

- Bauman MD, Water J VD (2020) Translational opportunities in the prenatal immune environment: Promises and limitations of the maternal immune activation model - PubMed. Neurobiology of disease 141: 104864.

- Meyer U (2014) Prenatal poly(i:C) exposure and other developmental immune activation models in rodent systems. Biological psychiatry 75(4): 307-315.

- Han VX, Patel S, Jones HF, Dale RC (2021) Maternal immune activation and neuroinflammation in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature reviews Neurology 17(9): 564-579.

- Knuesel I, Chicha L, Britschgi M, Schobel SA, Bodmer M, et al. (2014) Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nature reviews Neurology 10(11): 643-60.

- Guma E, Bordeleau M, González Ibáñez F, Picard K, Snook E, et al. (2022) Differential effects of early or late exposure to prenatal maternal immune activation on mouse embryonic neurodevelopment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America119(12): e2114545119.

- Rooij DV, Anagnostou E, Arango C, Auzias G, Behrmann M, et al. (2018) Cortical and Subcortical Brain Morphometry Differences Between Patients With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Healthy Individuals Across the Lifespan: Results From the ENIGMA ASD Working Group. The American journal of psychiatry 175(4): 359-369.

- Girard S, Tremblay L, Lepage M, Sébire G (2010) IL-1 receptor antagonist protects against placental and neurodevelopmental defects induced by maternal inflammation. J Immunol 184(7): 3997-4005.

- RE Kendell, IW Kemp (1989) Maternal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia - PubMed. Archives of general psychiatry 46(10): 87882.

- Chess S (1971) Autism in children with congenital rubella - PubMed. Journal of autism and childhood schizophrenia 1(1): 33-47.

- Byrne M, Agerbo E, Bennedsen B, Eaton WW, Mortensen PB, et al. (2007) Obstetric conditions and risk of first admission with schizophrenia: a Danish national register based study - PubMed. Schizophrenia research 97(1-3): 51-9.

- Brown AS, Derkits EJ (2010) Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies - PubMed. The American journal of psychiatry 167(3): 261-80.

- Mortensen PB, Norgaard-Peersen B, Waltoft BL, Sørensen TL, Hougaard D, et al. Toxoplasma gondii as a risk factor for early-onset schizophrenia: analysis of filter paper blood samples obtained at birth - PubMed. Biological psychiatry 61(5): 688-93.

- Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Hougaard DM, Petersen BN, Mors O, et al. (2010) A Danish National Birth Cohort study of maternal HSV-2 antibodies as a risk factor for schizophrenia in their offspring - PubMed. Schizophrenia research 122(1-3): 257-63.

- Sørensen HJ, Mortensen EL, Reinisch MJ, Mednick AS (2009) Association between prenatal exposure to bacterial infection and risk of schizophrenia - PubMed. Schizophrenia bulletin 35(3): 631-7.

- Clarke MC, Tanskanen A, Huttunen M, Whittaker JC, Cannon M, et al. (2009) Evidence for an interaction between familial liability and prenatal exposure to infection in the causation of schizophrenia - PubMed. The American journal of psychiatry 166(9): 1025-30.

- Buka SL, Cannon TD, Torrey EF, Yolken RH (2008) Maternal exposure to herpes simplex virus and risk of psychosis among adult offspring - PubMed. Biological psychiatry 63(8): 809-15.

- Zerbo O, Iosif AM, Delwiche L, Walker C, Hertz-Picciotto I, et al. (2011) Month of conception and risk of autism - PubMed. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 22(4): 469-75.

- Atladóttir HO, Thorsen P, Østergaard L, Schendel DE, Lemcke S, et al. (2010) Maternal infection requiring hospitalization during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders - PubMed. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 40(12): 1423-30.

- S Patel, A Masi, RC Dale, Whitehouse AJO, Pokorski I, et al. (2018) Social impairments in autism spectrum disorder are related to maternal immune history profile - PubMed. Molecular psychiatry 23(8): 17941797.

- Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, Odouli R, Water JVD, et al. (2005) Maternal autoimmune diseases, asthma and allergies, and childhood autism spectrum disorders: a case-control study - PubMed. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 159(2): 151-7.

- Dashraath P, Wong JLJ, Lim MXK, Lim LM, Li S, et al. (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy - PubMed. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 222(6): 521531.

- Kentner AC, Bilbo SD, Brown AS, Hsiao EY, McAllister AK, et al. (2019) Maternal immune activation: reporting guidelines to improve the rigor, reproducibility, and transparency of the model - PubMed. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 44(2): 245-258.

- Bergdolt L, Dunaevsky A (2019) Brain changes in a maternal immune activation model of neurodevelopmental brain disorders. Prog Neurobiol 175: 1-19.

- Amodeo DA, Lai CY, Hassan O, Mukamel EA, Behrens MM, etr al. (2019) Powell SB. Maternal immune activation impairs cognitive flexibility and alters transcription in frontal cortex. Neurobiol Dis 125: 211-218.

- O’Loughlin E, Pakan JMP, Yilmazer-Hanke D, McDermott KW (2017) Acute in utero exposure to lipopolysaccharide induces inflammation in the pre- and postnatal brain and alters the glial cytoarchitecture in the developing amygdala. Journal of neuroinflammation 14(1): 212.

- da Rosa N, de Medeiros FD, de Oliveira J, Laurentino AOM, Peretti EDM, et al. (2022) 6-Shogaol Exerts a Neuroprotective Factor in Offspring after Maternal Immune Activation in Rats. Dev Neurosci 44(1): 13-22.

- Ryan AM, Bauman MD (2022) Primate Models as a Translational Tool for Understanding Prenatal Origins of Neurodevelopmental Disorders Associated With Maternal Infection. Biological psychiatry Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging 7(5): 510-523.

- Bauman MD, Iosif AM, Smith SE, Bregere C, Amaral DG, et al. (2014) Activation of the maternal immune system during pregnancy alters behavioral development of rhesus monkey offspring. Biological psychiatry 75(4): 332-41.

- Gilmore JH, Jarskog LF (1997) Exposure to infection and brain development: cytokines in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research 24(3): 365-7.

- Wang R, Wu Z, Huang C, Hashimoto K, Yang L, et al. (2022) Deleterious effects of nervous system in the offspring following maternal SARSCoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry 12(1): 232.

- Meltzer A, Water JVD (2017) The Role of the Immune System in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 42(1): 284-298.

- Meyer U (2019) Neurodevelopmental Resilience and Susceptibility to Maternal Immune Activation. Trends in neurosciences 42(11): 793806.

- Takahashi N, Nishimura T, Harada T, Okumura A, Iwabuchi T, et al. (2023) Interaction of genetic liability for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and perinatal inflammation contributes to ADHD symptoms in children. Brain, behavior, & immunity – health 30: 100630.

- Ellman LM, Deicken RF, Vinogradov S, Kremen WS, Poole JH, et al. (2010) Structural brain alterations in schizophrenia following fetal exposure to the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-8. Schizophrenia research 121(1-3): 46-54.

- Wu WL, Hsiao EY, Yan Z, Mazmanian SK, Patterson PH, et al. (2017) The placental interleukin-6 signaling controls fetal brain development and behavior - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 62: 11-23.

- Kępa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Boroń-Kaczmarska A (2014) Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 concentration in patients with purulent, bacterial meningitis - own observations. Przegl Epidemiol 68(4): 645-9.

- Murray KN, Edye ME, Manca M, Vernon AC, Oladipo JM,et al. Evolution of a maternal immune activation (mIA) model in rats: Early developmental effects. Brain, behavior, and immunity 75: 48-59.

- Liang ZK, Xiong W, Wang C, Chen L, Zou X, et al. (2024) Resolving neuroinflammatory and social deficits in ASD model mice: Dexmedetomidine downregulates NF-κB/IL-6 pathway via α2AR. Brain, behavior, and immunity 119: 84-95.

- Smith SEP, Li J, Garbett K, Mirnics K, Patterson PH, et al. (2007) Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6 - PubMed. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27(40): 10695-702.

- García-Juárez M, Camacho-Morales A (2022) Defining the Role of Anti- and Pro-inflammatory Outcomes of Interleukin-6 in Mental Health - PubMed. Neuroscience 492: 32-46.

- Osman HC, Moreno R, Rose D, Rowland ME, Ciernia AV, et al. (2024) Impact of maternal immune activation and sex on placental and fetal brain cytokine and gene expression profiles in a preclinical model of neurodevelopmental disorders - PubMed. Journal of neuroinflammation 21(1): 118.

- Dahlgren J, Samuelsson AM, Jansson T, Holmäng A (2006) Interleukin-6 in the maternal circulation reaches the rat fetus in midgestation - PubMed. Pediatric research 60(2): 147-51.

- Zaretsky MV, Alexander JM, Byrd W, Bawdon RE (2004) Transfer of inflammatory cytokines across the placenta - PubMed. Obstetrics and gynecology 103(3): 546-50.

- Tossetta G, Paolinelli F, Avellini C, Salvolini E, Ciarmela P, et al. (2014) IL-1β and TGF-β weaken the placental barrier through destruction of tight junctions: an in vivo and in vitro study - PubMed. Placenta 35(7): 509-16.

- Hsiao EY, Patterson PH (2011) Activation of the maternal immune system induces endocrine changes in the placenta via IL-6 - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 25(4): 604-15.

- Kong X, Gong Z, Zhang L, Sun X, Ou Z, et al. (2019) JAK2/STAT3 signaling mediates IL-6-inhibited neurogenesis of neural stem cells through DNA demethylation/methylation - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 79: 159-173.

- Kathuria A, Lopez-Lengowski K, Roffman JL, Karmacharya R (2022) Distinct effects of interleukin-6 and interferon-γ on differentiating human cortical neurons - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 103: 97-108.

- Velasco S, Kedaigle AJ, Simmons SK, Nash A, Rocha M, et al. (2019) Individual brain organoids reproducibly form cell diversity of the human cerebral cortex. Nature 570(7762): 523-527.

- Sarieva K, Kagermeier T, Khakipoor S, Atay E, Yentur Z, et al. (2023) Human brain organoid model of maternal immune activation identifies radial glia cells as selectively vulnerable. Mol Psychiatry 28(12): 50775089.

- Rosine N, Miceli-Richard C (2020) Innate Cells: The Alternative Source of IL-17 in Axial and Peripheral Spondyloarthritis? Frontiers in immunology 11: 553742.

- Zwaag BVD, Franke L, Poot M, Hochstenbach R, Spierenburg HA, et al. (2009) Gene-network analysis identifies susceptibility genes related to glycobiology in autism - PubMed. PloS one 4(5): e5324.

- Al-Ayadhi LY, Mostafa GA (2012) Elevated serum levels of interleukin17A in children with autism - PubMed. Journal of neuroinflammation 9: 158.

- Suzuki K, Matsuzaki H, Iwata K, Kameno Y, Shimmura C, et al. (2011) Plasma cytokine profiles in subjects with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders - PubMed. PloS one 6(5): e204170.

- Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H, Kim S, Kim H, et al. (2016) The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science (New York, NY) 351(6276): 933-9.

- Li X, Fu Q, Zhong M, Long Y, Zhao F, et al. (2024) Quantitative proteomics of the miR-301a/SOCS3/STAT3 axis reveals underlying autism and anxiety-like behavior - PubMed. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids 35(1): 102136.

- Kim H (2023) Visualization of maternal IL-17a across the placental membrane - PubMed. Science progress 106(3): 68504231195500.

- Lee JY, Kim H (2024) IL-17A Cytokine-Regulated Glut1 Expression in Placenta Cells - PubMed. Current issues in molecular biology 46(7): 7386-7394.

- Yu D, Li T, Delpech JC, Zhu B, Kishore P, et al. (2022) Microglial GPR56 is the molecular target of maternal immune activation-induced parvalbumin-positive interneuron deficits. Science advances (18): eabm2545.

- Sasaki T, Tome S, Takei Y (2020) Intraventricular IL-17A administration activates microglia and alters their localization in the mouse embryo cerebral cortex - PubMed. Molecular brain 13(1): 93.

- Kalish BT, Kim E, Finander B, Duffy EE, Kim H, et al. (2021) Maternal immune activation in mice disrupts proteostasis in the fetal brain. Nat Neurosci 24(2):204-213.

- Fan L, Zeng X, Jiang Y, Zheng D, Wang H, et al. (2024)Yigansan ameliorates maternal immune activation-induced autism-like behaviours by regulating the IL-17A/TRAF6/MMP9 pathway: Network analysis and experimental validation - PubMed. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 128:155386.

- Kim E, Paik D, Ramirez RN, Biggs DG, Park Y, et al. (2022) Maternal gut bacteria drive intestinal inflammation in offspring with neurodevelopmental disorders by altering the chromatin landscape of CD4(+) T cells. Immunity 55(1): 145-158.e7.

- Estes ML, McAllister AK (2015) Immune mediators in the brain and peripheral tissues in autism spectrum disorder - PubMed. Nature reviews Neuroscience 16(8): 469-86.

- Arrode-Bruses G, Bruse JL (2012) Maternal immune activation by poly I:C induces expression of cytokines IL-1β and IL-13, chemokine MCP1 and colony stimulating factor VEGF in fetal mouse brain - PubMed. Journal of neuroinflammation 9: 83.

- Boksa P (2010) Effects of prenatal infection on brain development and behavior: a review of findings from animal models - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 24(6): 881-97.

- O’Roak BJ, Deriziotis P, Lee C, Vives L, Schwartz JJ, et al. (2020) Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations - PubMed. Nature genetics 43(6): 585-9.

- Saad K, Abdallah AEM, Abdel-Rahman AA, Al-Atram AA, AbdelRaheem YF, et al. (2020) Polymorphism of interleukin-1β and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist genes in children with autism spectrum disorders - PubMed. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry 103: 09999.

- Borreca A, Mantovani C, Desiato G, Corradini I, Filipello F, et al. (2024) Loss of interleukin 1 signaling causes impairment of microglia- mediated synapse elimination and autistic-like behaviour in mice - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 117: 493-509.

- Kelly A, Vereker E, Nolan Y, Brady M, Barry C, et al. (2003) Activation of p38 plays a pivotal role in the inhibitory effect of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1 beta on long term potentiation in rat dentate gyrus - PubMed. The Journal of biological chemistry 278(21): 19453-62.

- Church JS, Tamayo JM, Ashwood P, Schwartzer JJ (2021) Repeated allergic asthma in early versus late pregnancy differentially impacts offspring brain and behavior development - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 93: 66-79.

- Gregersen R, Lambersten K, Finsen B (2000) Microglia and macrophages are the major source of tumor necrosis factor in permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice - PubMed. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 20(1): 53-65.

- Tracey D, Klareskog L, Sasso EH, Salfeld JG, Tak PP, et al. (2008) Tumor necrosis factor antagonist mechanisms of action: a comprehensive review - PubMed. Pharmacology & therapeutics 117(2): 244-79.

- Meyer U, Nyffeler M, Engler A, Urwyler A, Schedlowski M, et al. (2006) The time of prenatal immune challenge determines the specificity of inflammation-mediated brain and behavioral pathology - PubMed. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 26(18): 4752-62.

- Takada R, Toritsuka M, Yamauchi T, Ishida R, Kayashima Y, et al. (2024) Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced macrophages of individuals with autism spectrum disorder adversely affect neuronal dendrites through the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines - PubMed. Molecular autism 15(1): 10.

- Mcewen BS, Morrison JH (2013) The brain on stress: vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course - PubMed. Neuron 79(1): 16-29.

- Nie X, Kitaoka S, Tanaka K, Segi-Nishida E, Imoto Y, et al. (2018) The Innate Immune Receptors TLR2/4 Mediate Repeated Social Defeat Stress-Induced Social Avoidance through Prefrontal Microglial Activation - PubMed. Neuron 99(3): 464-479.

- Escoubas CC, Dorman LC, Nguyen PT, Lagares-Linares C, Nakajo H, et al. (2024) Type-I-interferon-responsive microglia shape cortical development and behavior - PubMed. Cell 187(8): 1936-1954.

- Vikman KS, Owe-Larsson B, Brask j, Kristensson KS, Hill RH, et al. (2001) Interferon-gamma-induced changes in synaptic activity and AMPA receptor clustering in hippocampal cultures - PubMed. Brain research 896(1-2): 18-29.

- Ahmad SF, Zoheir KMA, Ansari MA, Nadeem A, Bakheet SA, et al. (2017) Dysregulation of Th1, Th2, Th17, and T regulatory cell-related transcription factor signaling in children with autism - PubMed. Molecular neurobiology 54(6): 4390-4400.

- Mustafa GA, Shehab AA, Fouad NR (2010) Frequency of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of Egyptian children with autism - PubMed. Journal of child neurology 25(3): 32835.

- Moaaz M, Youssry S, Elfatatry A, Rahman MAE (2019) Th17/Treg cells imbalance and their related cytokines (IL-17, IL-10 and TGF-β) in children with autism spectrum disorder - PubMed. Journal of neuroimmunology 337: 577071.

- Mandal M, Marzouk AC, Donnelly R, Ponzio NM (2010) Preferential development of Th17 cells in offspring of immunostimulated pregnant mice - PubMed. Journal of reproductive immunology 87(1-2): 97-100.

- Mandol M, Marzouk AC, Doneely R, Ponzio NM (2011) Maternal immune stimulation during pregnancy affects adaptive immunity in offspring to promote development of TH17 cells - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 25(5): 863-71.

- Ponzio NM, Mandal M, Elkabes S, Zhang P, Sadoshima J, et al. (2013) Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype Induced by Maternal Immune Stimulation During Pregnancy | IntechOpen. Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorders - Volume I.

- Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Chow J, Mazmanian SK, Patterson PH, et al. (2012) Modeling an autism risk factor in mice leads to permanent immune dysregulation - PubMed. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(31): 1277681.

- Li Y, Yao G, Wang R, Zhu J, Li H, et al. (2024) Maternal immune activation mediated prenatal chronic stress induces Th17/Treg cell imbalance may relate to the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway in offspring rats - PubMed. International immunopharmacology 126: 111308.

- Xu Z, Zhang X, Chang H, Kong Y, Ni Y, et al. (2021) Rescue of maternal immune activation-induced behavioral abnormalities in adult mouse offspring by pathogen-activated maternal Treg cells - PubMed. Nature neuroscience 24(6): 818-830.

- Xu Z, Zhang X, Chang H, Kong Y, Ni Y,et al. (2021) Rescue of maternal immune activation-induced behavioral abnormalities in adult mouse offspring by pathogen-activated maternal T(reg) cells. Nat Neurosci 24(6): 818-830.

- Denkers EY, Gazzinelli RT (1998) Regulation and function of T-cellmediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clinical microbiology reviews 11(4): 569-88.

- Luan R, Cheng H, Li L, hao Q, Liu H, et al. (2015) Maternal Lipopolysaccharide Exposure Promotes Immunological Functional Changes in Adult Offspring CD4+ T Cells - PubMed. American journal of reproductive immunology 73(6): 522-35.

- Zager A, Pinheiro ML, Ferraz-de-Paula V, Ribeiro A, Palermo-Neto J, et al. (2013) Increased cell-mediated immunity in male mice offspring exposed to maternal immune activation during late gestation - PubMed. International immunopharmacology 17(3): 633-7.

- Matute JD, Finander B, Pepin D, Ai X, Smith NP, et al. (2022) Singlecell immunophenotyping of the fetal immune response to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection in late gestation - PubMed. Pediatric research 91(5): 1090-1098.

- Shen C, Zhu X, Chang H, Li C, Hou M, et al. (2024) The rebalancing of the immune system at the maternal-fetal interface ameliorates autismlike behavior in adult offspring. Cell reports 43(10):114787.

- Shen C, Zhu X, Chang H, Li C, Hou M, et al. (2024) The rebalancing of the immune system at the maternal-fetal interface ameliorates autismlike behavior in adult offspring - PubMed. Cell reports 43(10): 114787.

- Kim S, Kim H, Yim YS, Ha S, Atarash K, et al. (2017) Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature 549(7673): 528-532.

- Colonna M, Butovsky O (2017) Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration - PubMed. Annual review of immunology 35(1): 441-468.

- Squarzoni P, Oller G, Hoeffel G, Pont-Lezica L, Rostaing P, et al. (2014) Microglia modulate wiring of the embryonic forebrain. Cell reports 8(5):1271-9.

- Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, et al. (2011) Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 333(6048): 1456-8.

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, et al. (2012) Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 74(4): 691-705.

- Gunner G, Cheadle L, Johnson KM, Ayata P, Badimon A, et al. (2019) Sensory lesioning induces microglial synapse elimination via ADAM10 and fractalkine signaling. Nat Neurosci 22(7): 1075-1088.

- Block ML, Hong JS (2005) Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog Neurobiol 76(2): 77-98.

- Smolders S, Notter T, Smolders SMT, Rigo JM, Brône B, et al. (2018) Controversies and prospects about microglia in maternal immune activation models for neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain, behavior, and immunity 73: 51-65.

- Luo L, Chen J, Wu Q, Yuan B, Hu C, et al. (2023) Prenatally VPA exposure is likely to cause autistic-like behavior in the rats offspring via TREM2 down-regulation to affect the microglial activation and synapse alterations. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 99: 104090.

- Ozaki K, Kato D, Ikegami A, Hashimoto A, Sugio S, et al. (2020) Maternal immune activation induces sustained changes in fetal microglia motility. Sci Rep 10(1):V21378.

- González H, Elgueta D, Montoya A, Pacheco R (2014) Neuroimmune regulation of microglial activity involved in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases - PubMed. Journal of neuroimmunology 274(1-2): 1-13.

- Sousa NA, Oliveira GAL, de Oliveira AP, Lopes ALF, Lles B, et al. (2020) Novel Ocellatin Peptides Mitigate LPS-induced ROS Formation and NF-kB Activation in Microglia and Hippocampal Neurons. Sci Rep 10(1): 2696.

- Antony JM, Paquin A, Nutt SL, Kaplan DR, Miller FD, et al. (2011) Endogenous microglia regulate development of embryonic cortical precursor cells - PubMed. Journal of neuroscience research 89(3): 286-98.

- Cunningham CL, Martínez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC (2013) Microglia regulate the number of neural precursor cells in the developing cerebral cortex - PubMed. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 33(10): 4216-33.

- Thion MS, Mosser CA, Férézou I, Grisel P, Baptista S, et al. (2019) Biphasic Impact of Prenatal Inflammation and Macrophage Depletion on the Wiring of Neocortical Inhibitory Circuits. Cell reports 28(5): 1119-1126.e4.

- Matcovitch-Natan O, Winter DR, Giladi A, Aguilar SV, Spinrad A, et al. (2016) Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science 353(6301): aad8670.

- Chamera K, Kotarska K, Szuster-Głuszczak M, Trojan E, Skórkowska A, et al. (2020) The prenatal challenge with lipopolysaccharide and polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid disrupts CX3CL1-CX3CR1 and CD200-CD200R signalling in the brains of male rat offspring: a link to schizophrenia-like behaviours. Journal of neuroinflammation 17(1): 247.

- Cossío LFD, Guzmán A, Veldt SVD, Luheshi GN (2017) Prenatal infection leads to ASD-like behavior and altered synaptic pruning in the mouse offspring - PubMed. Brain, behavior, and immunity 63: 8898.

- Ueno M, Fujita Y, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y, Kikuta J, et al. (2013) Layer V cortical neurons require microglial support for survival during postnatal development. Nat Neurosci 16(5): 543-51.

- Fujita Y, Yamashita T (2021) Neuroprotective function of microglia in the developing brain. Neuronal signaling 5(1): Ns20200024.

- Cornell J, Salinas S, Huang HY, Zhou M (2022) Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory - PubMed. Neural regeneration research 17(4): 705-716.

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [65, 66];

- Su L, Zhang M, Ji F, Zhao J, Wang Y, et al. (2024) Microglia homeostasis mediated by epigenetic ARID1A regulates neural progenitor cells response and leads to autism-like behaviors - PubMed. Molecular psychiatry 29(6): 1595-1609.

- Kim HJ, Cho MH, Shim WH, Kim JK, Jeon EY, et al. (2017) Deficient autophagy in microglia impairs synaptic pruning and causes social behavioral defects. Mol Psychiatry 22(11): 1576-1584.

- Tang G, Gudsnuk K, Kuo SH, Cotrina ML, Rosoklija G, et al. (2014) Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits - PubMed. Neuron 83(5): 1131-43.

- Su X, Wang G, Liu S, Li J, Shao M, et al. (2024) Autophagy defects at weaning impair complement-dependent synaptic pruning and induce behavior deficits - PubMed. Journal of neuroinflammation 21(1): 239.

- Newman LE, Shadel GS (2018) Pink1/Parkin link inflammation, mitochondrial stress, and neurodegeneration. The Journal of cell biology 217(10): 3327-3329.

- Morris G, Maes M (2014) Mitochondrial dysfunctions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metabolic brain disease 29(1): 19-36.

- Stankovic ND, Teodorczyk M, Ploen R, Zipp F, Schmidt MHH, et al. (2016) Microglia-blood vessel interactions: a double-edged sword in brain pathologies. Acta Neuropathol 131(3): 347-63.

- Varatharaj A, Galea I (2017) The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain, behavior, and immunity 60: 1-12.

- Haruwaka K, Ikegami A, Tachibana Y, Ohno N, Konishi H, et al. (2019) Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation. Nat Commun 10(1): 5816.

- Hayes LN, An K, Carloni E, Li F, Vincent E, et al. (2022) Prenatal immune stress blunts microglia reactivity, impairing neurocircuitry. Nature 610(7931): 327-334.

- Xiao L, Zhang F, Zhao F (2022) Large-scale microbiome data integration enables robust biomarker identification. Nature computational science 2(5): 307-316.

- Xiao L, Zhou T, Zuo Z, Sun N, Zhao F (2024) Spatiotemporal patterns of the pregnancy microbiome and links to reproductive disorders. Science bulletin 69(9): 1275-1285.

- Sgritta M, Dooling SW, Buffington SA, Momin EN, Francis MB, et al. (2019) Mechanisms Underlying Microbial-Mediated Changes in Social Behavior in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuron 101(2): 246-259.e6.

- Buffington SA, Dooling SW, Sgritta M, Noecker C, Murillo OD, et al. (2021) Dissecting the contribution of host genetics and the microbiome in complex behaviors. Cell 184(7): 1740-1756.e16.

- Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, Sharon G, Hyde MR, et al. (2013) Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell 155(7): 1451-63.

- Zhou Q, Shen B, Huang R, Liu H, Zhang W, et al. (2022) Bacteroides fragilis strain ZY-312 promotes intestinal barrier integrity via upregulating the STAT3 pathway in a radiation-induced intestinal injury mouse model. Frontiers in nutrition 9: 1063699.

- Kim JW, Seung H, Kim KC, Gonzales ELT, Oh HA, et al. (2017) Agmatine rescues autistic behaviors in the valproic acid-induced animal model of autism. Neuropharmacology 113(Pt A)71-81.

- Kim S, Kim H, Yim YS, Ha S, Atarashi K, et al. (2017) Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring - PubMed. Nature 549(7673): 528-532.

- Erny D, Angelis ALHD, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski, O et al. (2015) Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS - PubMed. Nature neuroscience 18(7): 965-77.

- Thion MS, Low D, Silvin A, Chen J, Grisel P, et al. (2018) Microbiome Influences Prenatal and Adult Microglia in a Sex-Specific Manner. Cell 172(3): 500-516.e16.

- Erny D, Angelis ALHd, Prinz M (2016) Communicating systems in the body: how microbiota and microglia cooperate. Immunology 150(1): 7-15.

- Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, Sharon G, Hyde ER, et al. (2013) Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders - PubMed. Cell 155(7): 1451-63.

- Oh-Nishi A, Obayashi S, Sugihara I, Minamimoto T, Suhara T, et al. (2010) Maternal immune activation by polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidilic acid injection produces synaptic dysfunction but not neuronal loss in the hippocampus of juvenile rat offspring - PubMed. Brain research 1363: 170-9.

- Wu J, Zhang J, Chen X, Wettschurack K, Que Z, et al. (2024) Microglial over-pruning of synapses during development in autism-associated SCN2A-deficient mice and human cerebral organoids. Molecular Psychiatry 29(8): 2424-2437.

- Zhan Y, Paolicelli RC, forazzini FS, Weinhard L, Bolasco G, et al. (2014) Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior - PubMed. Nature neuroscience 17(3): 400-6.

- Baines KJ, Hillier DM, Haddad FL, Rajakumar N, Schmid S, et al. (2020) Maternal Immune Activation Alters Fetal Brain Development and Enhances Proliferation of Neural Precursor Cells in Rats - PubMed. Frontiers in immunology 11: 1145.

- Li X, Fu Q, Zhong M, Long Y, Zhao F, et al. (2024) Quantitative proteomics of the miR-301a/SOCS3/STAT3 axis reveals underlying autism and anxiety-like behavior. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 35(1): 102136.

- Lu J, Fan X, Lu L, Yu Y, Markiewicz E, et al. (2023) Limosilactobacillus reuteri normalizes blood-brain barrier dysfunction and neurodevelopment deficits associated with prenatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide. Gut microbes 15(1): 2178800.

- Osman HC, Moreno R, Rose D, Rowland ME, Ciernia AV, et al. (2024) Impact of maternal immune activation and sex on placental and fetal brain cytokine and gene expression profiles in a preclinical model of neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of neuroinflammation 21(1): 118.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.