Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery in Advanced Cataract with Severe Corneal Endothelial Decompensation: A Case Report

by Łukasz Drzyzga1,2, Dorota Śpiewak1,2*, Mariola Dorecka1,3, Dorota Wyględowska-Promieńska1,3

1Department of Ophthalmology, Prof. K. Gibiński University Hospital Center, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland

2Clinical Ophthalmology Center OKOLUX, Katowice, Poland

3Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medical Sciences in Katowice, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland

*Corresponding Author: Dorota Śpiewak, Department of Ophthalmology, Prof. K. Gibiński University Hospital Center, Medical University of Silesia, 35 Ceglana Street, 40-514 Katowice, Poland

Received Date: 09 February 2026

Accepted Date: 13 February 2026

Published Date: 15 February 2026

Citation: Drzyzga Ł, Śpiewak D, Dorecka M, Wyględowska-Promieńska D (2026) Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery in Advanced Cataract with Severe Corneal Endothelial Decompensation: A Case Report. J Surg 11: 11567 DOI: https://doi.org/10.29011/2575-9760.011567

Abstract

Introduction: Advanced cataract concomitant with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy and corneal endothelial decompensation, secondary angle-closure glaucoma, and Age-Related Neovascular Macular Degeneration (AMD) represents a significant surgical challenge. Appropriate selection of the cataract extraction technique is crucial to minimize further endothelial damage and eliminate the need for keratoplasty.

Case Presentation: An 88-year-old woman presented with severe vision loss, corneal edema, and shallow anterior chambers. Diagnostic imaging revealed bilateral subluxated brunescent cataracts, Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, secondary glaucoma, and exudative AMD. A multifaceted treatment strategy was implemented due to the complexity of the case. This included modified double-incision Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery (MSICS) with capsular tension rings in both eyes. Zonular dehiscence in the left eye was managed using an optic capture technique. Concurrently, the patient received intravitreal faricimab injections to treat AMD, which successfully improved retinal morphology. Postoperatively, the patient showed significant improvement. Corneal edema largely resolved, anterior chambers deepened, and intraocular pressure stabilized. Best-corrected visual acuity improved to 0.6 in the right eye and 0.2 in the left eye, allowing the patient to resume independent living and deferring the need for planned bilateral posterior lamellar keratoplasty.

Conclusions: MSICS is a safe and effective surgical option in patients with advanced cataract and severely compromised corneal endothelial function. In selected cases, meticulous surgical planning and a multifaceted treatment approach may result in sufficient corneal recovery, enabling postponement or even avoidance of keratoplasty.

Keywords: Advanced Cataract; Corneal Decompensation; Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (ECCE); Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy; Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery (MSICS)

Introduction

Cataract surgery with implantation of an artificial Intraocular Lens (IOL) is among the most frequently performed surgical procedures worldwide. Its primary goal is to restore visual acuity impaired by clouding of the natural lens [1]. Clear vision restoration is the main indicator of successful cataract surgery. Three leading options for surgical cataract treatment are phacoemulsification, Extracapsular Cataract Extraction (ECCE), and Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery (MSICS). Phacoemulsification is the most used surgical technique and is considered the gold standard for cataract surgery, owing to its high effectiveness and minimal invasiveness [1]. It involves creating a main port incision of 2-3 mm in length and 2.2-2.4 mm in width near the corneal limbus in the superior or temporal quadrant, and two side ports, each typically about 1.2 mm wide. Subsequently, capsulorhexis, high-frequency ultrasoundinduced lens fragmentation, and suction complete lens removal. Lens fragmentation can also be performed by femtosecond laserassisted cataract surgery, which softens the cataract and facilitates its liquefaction, thereby reducing the energy and time required for phacoemulsification [2]. A balanced salt solution maintains anterior chamber depth and prevents collapse during the procedure. After removal of the natural lens, a foldable IOL is implanted through the main port [3]. Corneal incisions do not require sutures, as they self-seal. This technique induces a lower rate of astigmatism than larger corneal incisions, and the wound has greater anatomical stability and fewer complications [1,3]. Several modifications of the technique have been developed to reduce energy use, improve safety, and preserve corneal endothelial cells and visual acuity. These include techniques such as “direct-chop,” “stop-and-chop,” “divide-and-conquer,” “phaco-chop,” and femtosecond laserassisted cataract surgery FLACS [1,4,5].

Despite its many benefits, phacoemulsification is not without risks. Significant potential complications include infection, retinal detachment, glaucoma [6], and corneal decompensation, and the ultrasound energy contributes to mechanical and thermal damage to endothelial cells [1,7-11]. Furthermore, acoustic cavitation leads to microbubble formation in the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber, which can damage structures near the phaco tip, including the corneal endothelium, iris, and lens capsule, leading to increased postoperative inflammation, corneal edema [12], limited postoperative vision, and a slower recovery. Moreover, the collapse of cavitation bubbles generates Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which contribute to oxidative stress and subsequent cellular apoptosis [1,13]. Such damage, particularly corneal decompensation, might require further surgical intervention, such as keratoplasty [14]. Surgeons use ECCE, an older, more invasive technique, in specific clinical scenarios because it causes less endothelial cell loss than other methods. The procedure requires making a 10-12 mm incision at the corneal limbus, followed by capsulorhexis. Injection of a viscoelastic material behind the lens nucleus delivers it into the anterior chamber, from which it is removed mechanically with a loop. The posterior capsule remains intact, allowing implantation of an IOL. However, ECCE necessitates suturing the corneal incision and is associated with a high rate of postoperative ocular complications, including corneal haze and edema, shallow anterior chamber, hyphema, subconjunctival hemorrhages, and posterior capsule rupture during IOL implantation [15].

MSICS is an enhancement of ECCE that involves performing a limbal peritomy, followed by a trapezoid-shaped incision at the superior sclera, 1.5-2 mm behind the limbus. The internal opening width (9-10 mm) is broader than the external opening (6-7 mm). The scleral tunnel length is 2-3 mm centrally and slightly longer peripherally. The incision extends 1-1.5 mm into the clear cornea. Lens nucleus removal follows the same steps as in ECCE. The remaining cortical material is removed by manual irrigation. The procedure ends with implantation of an artificial IOL and one or two sutures on the conjunctival wound [16]. MSICS is associated with a lower rate of refractive astigmatism than ECCE, and the incisions are less traumatic to the trabecular meshwork. The wounds are selfsealing in MSICS, reducing the risk of postoperative complications [15,17]. MSICS is as safe for the corneal endothelium in cases of dense cataracts as phacoemulsification is in cases of soft cataracts and is similarly effective. Most studies on MSICS report transient corneal epithelial edema, which usually resolves within the first week after surgery [16]. A modified, double-incision MSICS involves creating a scleral tunnel for removing the lens nucleus and corneal tunnels for removing the remaining cortical material. This method is safe and effective in patients with hard nucleus cataracts and low corneal endothelial cell density. Double-incision MSICS maintains a more stable anterior chamber during cortical material aspiration than when this step is performed through an intrascleral tunnel. We describe a case of bilateral subluxated brunescent cataracts, complicated by Fuchs endothelial dystrophy, secondary glaucoma, and exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD), for which we elected to perform double-incision MSICS.

Case Presentation

An 88-year-old woman presented to the Okolux Clinical Ophthalmology Center in Katowice, Poland, with significant visual acuity deterioration in both eyes.

Initial Examinations

Distance visual acuity, assessed using Snellen charts, was 0.15 in

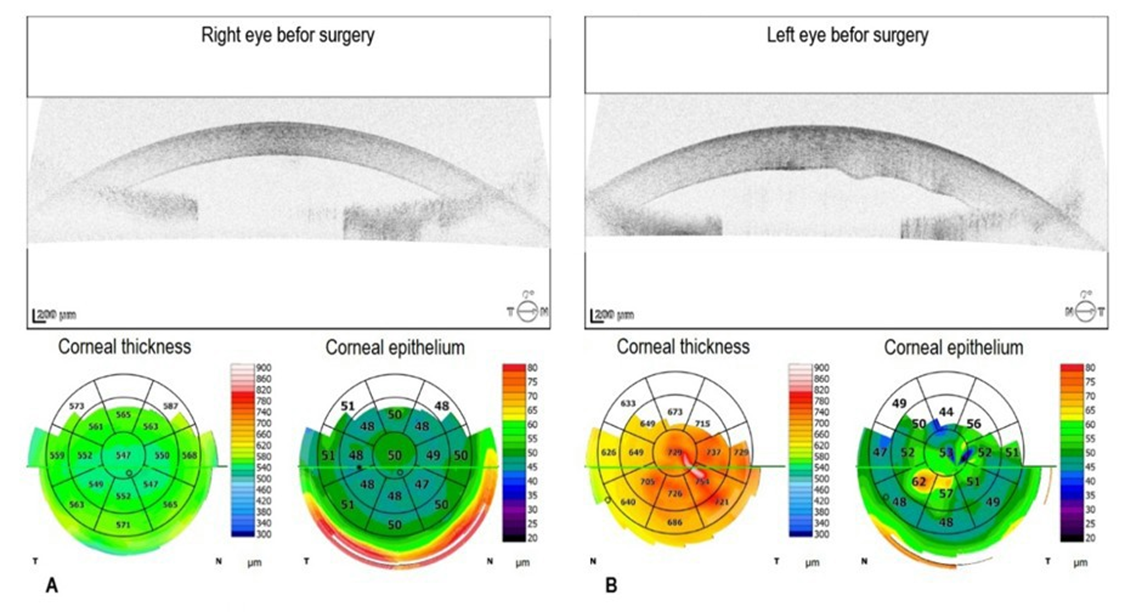

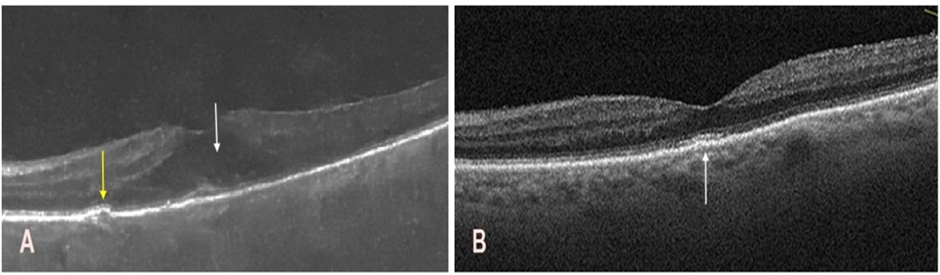

the right eye and counting fingers in the left eye. Optical correction did not improve visual acuity. Since the autorefraction test could not be performed, spectacle correction was empirical. Intraocular pressure, measured using a non-contact iCare tonometer (Icare Finland Oy, Vantaa, Finland), was 22 mmHg in the right eye and 23 mmHg in the left eye. Due to corneal edema, particularly in the left eye, these values may have been underestimated; therefore, digital palpation confirmed mildly elevated ocular tension bilaterally. Endothelial cell density in the right eye was 1469 cells/mm²; measurement could not be performed in the left eye because of advanced bullous keratopathy. Slit-lamp examination revealed bilateral corneal edema, more pronounced in the left eye, shallow anterior chambers, and brunescent, subluxated cataracts. Fundus visualization in the right eye was limited, with only the outlines of the optic disc and retinal vessels visible, and a preserved red fundus reflex visible. No fundus view was obtainable in the left eye. Anterior segment imaging using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; REVO 80, Optopol Technology Sp. z o.o., Zawiercie, Poland) showed a hyperreflective endothelium with normal Central Corneal Thickness (CCT) in the right eye (Figure 1A) and corneal edema with increased corneal thickness and Descemet membrane folds in the left eye (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Preoperative spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the right and left eye. A. In the right eye, the central corneal thickness is 547 µm. B. In the left eye, the central corneal thickness is increased by 729 µm with Descemet membrane folds. The corneal epithelial thickness map shows focal epithelial thickening consistent with edema with bullous keratopathy.

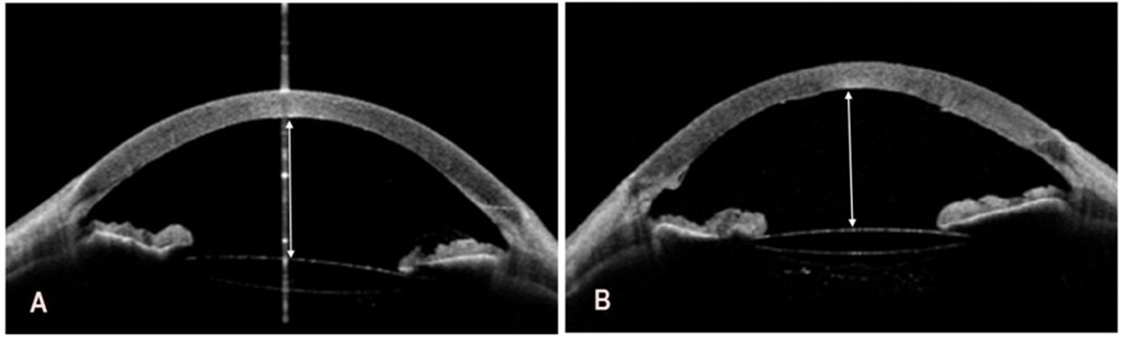

Swept-source OCT using CASIA 2 (Tomey Corporation, Nagoya, Japan) revealed marked shallowing of the anterior chambers, slit-like and nearly completely closed iridocorneal angles, and intumescent lenses in both eyes, particularly in the left eye (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2: Preoperative swept-source optical coherence tomography of the right and left eye. A. The depth of the anterior chamber to the corneal endothelium in the right eye is 2.03 mm (white double-headed arrow). B. In the left eye, the depth of the anterior chamber to the corneal endothelium is even smaller and amounts to 1.42 mm (white double-headed arrow).

Automatic calculation of IOL power using the IOL Master 700 optical biometer (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) was not possible. The IOL power was therefore calculated based on keratometry from corneal topography and manual A-scan ultrasound biometry. Multiple measurements were performed, and the most reliable values were entered into the IOL Master 700 system. In the left eye, keratometry readings were K1 = 46.30 D at an axis of 42°, and K2 = 49.70 D at an axis of 132°. The axial length (AL) was 22.42 mm. In the right eye, keratometry readings were K1 = 47.13 D at an axis of 4°, and K2 = 46.84 D at an axis of 94°, with an AL of 22.66 mm. Macular OCT using the OCT Solix device (Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) revealed exudative AMD in the right eye (Figure 4A). The left fundus could not be visualized.

Diagnosis

Based on the examinations performed, the patient was diagnosed with bilateral subluxated mature brunescent cataracts; corneal decompensation and bullous keratopathy in the left eye; advanced Fuchs endothelial dystrophy in both eyes; secondary glaucoma with iridocorneal angle narrowing in both eyes; status post bilateral LPI; and exudative age-related macular degeneration in the right eye. Topical pharmacological treatment was initiated, including dorzolamide antiglaucoma eye drops (Rozalin, Adamed Pharma S.A., Pieńków, Poland) and sorbitol-containing hypertonic eye drops to reduce corneal edema (Cornesin, NTC s.r.l., Milan, Italy).

Treatment Strategy

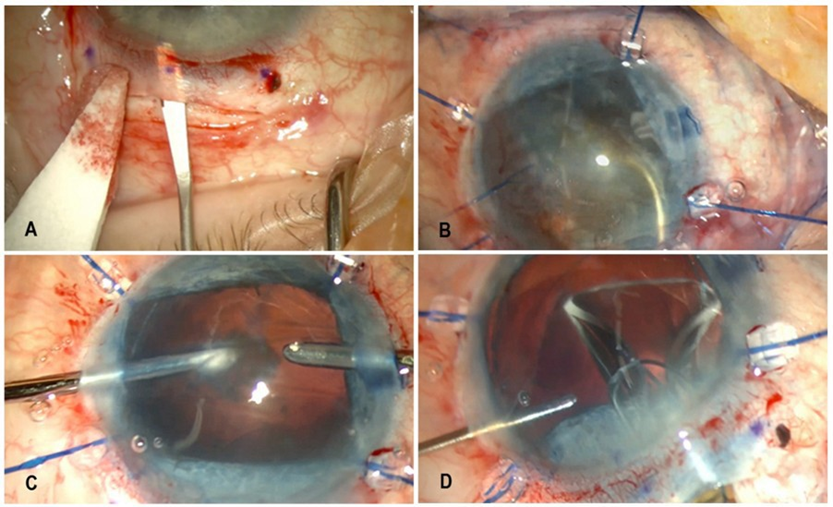

The patient was referred for cataract surgery at the Ophthalmology Department at Prof. Kornel Gibiński University Hospital Center in Katowice, Poland, with bilateral posterior lamellar keratoplasty (DSAEK) planned for a later stage. The decision to perform elective keratoplasty was based on advanced Fuchs endothelial dystrophy and bullous keratopathy. The left eye was qualified for surgery first due to poorer visual acuity and more advanced pathology in the anterior segment. Owing to the significantly reduced endothelial cell count, as assessed indirectly by corneal decompensation and bullous keratopathy, we used a modified double-incision MSICS (Figure 3A-D). A superior limbal peritomy was performed, followed by gentle cauterization of the episcleral vessels. Subsequently, a 7 mm scleral tunnel incision was made 1.5-2 mm posterior to the limbus and extended 1-1.5 mm into the clear cornea. The tunnel was trapezoidal, with an internal opening of 9-10 mm in diameter. Two side-port incisions were also made. Due to iris flaccidity and inadequate pupillary dilation, iris retractors were used. Trypan blue dye was administered to improve visualization of the lens capsule. Following capsulorhexis and injection of a viscoelastic substance, the lens nucleus was extracted with a loop, and the remaining cortical material was aspirated bimanually. An anterior vitrectomy was performed at the site of zonular dehiscence, and a Capsular Tension Ring (CTR) was implanted to manage significant zonular damage. A three-piece IOL, AcrySof MA60AC (Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA), with a power of +19.5 D, was implanted. The haptics were placed in the ciliary sulcus, while the optic was fixed using the optic capture technique, ensuring lens stability and better IOL centration within the eyeball. The scleral tunnel was closed with two single 7-0 absorbable sutures, and the conjunctiva was closed without sutures using diathermy.

Figure 3: Selected stages of left eye surgery using the method of modified double-incision MSICS. A. Scleral tunnel incision. B. Placement of iris retractors and lens nucleus extraction using a loop. C. Bimanual aspiration of the remaining cortical material. D. A three-piece intraocular lens implantation; optic fixation was done using the optic capture technique.

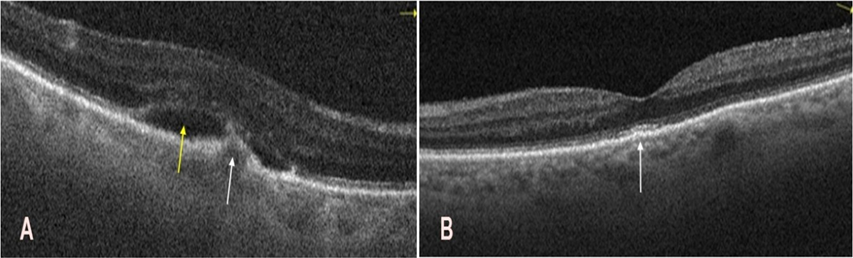

In parallel, treatment for exudative AMD was initiated in the right eye. This included four intravitreal injections of the anti-VEGF agent faricimab (Vabysmo, Roche Pharma AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany) at monthly intervals before cataract surgery, resulting in a favorable therapeutic outcome. Lesion regression was confirmed using macular OCT (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4: Optical coherence tomography of the macula in the right eye before and after intravitreal faricimab injections. A. Before injections, a hyperreflective subretinal, subfoveal structure was noted (white arrow), accompanied by a hyporeflective subretinal space (yellow arrow). These findings are indicative of active macular neovascularization. B. After four injections, restoration of the foveal contour is visible, with mild irregularities of the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptor layers (white arrows).

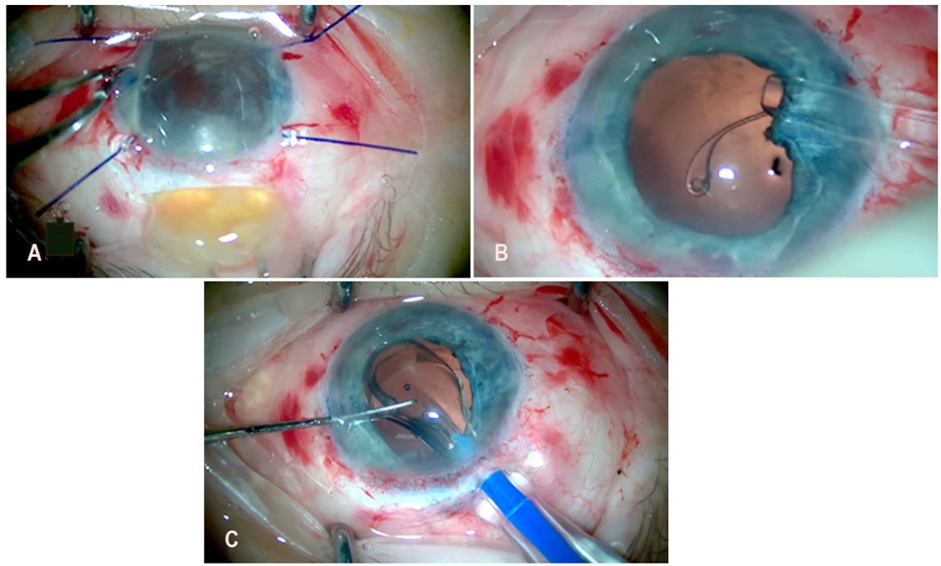

Cataract surgery in the right eye was performed three months after cataract surgery in the left eye. In the right eye, the same technique was used as in the left eye, with some changes (Figure 5A-C). A CTR was used due to lax zonular fibers, rather than ruptured ones. It was inserted through a side port, positioning the midpoint of the ring loop in the area of greatest lens subluxation. The degree of lens subluxation was less pronounced than in the left eye, allowing effective capsular stabilization. A single-piece, monofocal IOL, AcrySof IQ SN60WF (Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA), with a power of +20.0 D, was implanted into the capsular bag.

Figure 5: Selected stages of right eye surgery using the method of modified double-incision MSICS. A. Extracapsular removal of the lens nucleus through the scleral tunnel incision using a loop. B. Implantation of a capsular tension ring through a side-port incision. C. Implantation of a single-piece intraocular lens into the capsular bag.

Following improvement in the transparency of the optical media, left macular OCT revealed exudative age-related macular degeneration (Figure 6A), which was treated as in the right eye, resulting in improved retinal morphology and suppression of neovascular activity (Figure 6B).

Figure 6: Optical coherence tomography of the macula in the left eye before and after the intravitreal faricimab injections. A. Persistent corneal edema limited fundus visualization and resulted in suboptimal image quality. A hyporeflective space is observed within the intraretinal layers (white arrow), along with a small drusenoid elevation and minor irregularities at the level of the photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium (yellow arrow). B. Restoration of the foveal contour with mild irregularities in the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptor layers, predominantly in the subfoveal region (white arrow).

Treatment Outcomes

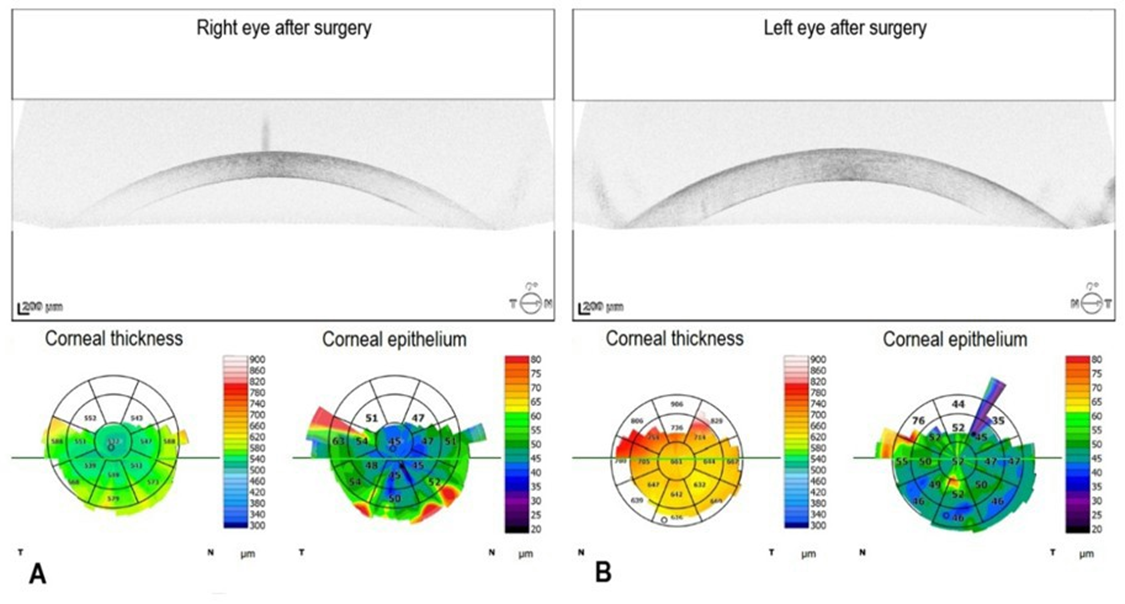

The patient attended regular follow-up appointments throughout the treatment course. Postoperative management for both eyes included dorzolamide (Rozalin, Adamed Pharma S.A. Pieńków, Poland) twice daily, 0.1% dexamethasone (Polpharma S.A., Starogard Gdański, Poland) five times daily, and a fluoroquinolone antibiotic (Oftaquix; Santen Oy, Tampere, Finland) five times daily. A transient increase in corneal thickness was observed one month after cataract surgeries in both eyes. CCT was 637 µm in the right eye and 713 µm in the left eye. A significant improvement in visual acuity in both eyes was observed four months after surgery, allowing reliable autorefraction measurements. In the right eye, Uncorrected Visual Acuity (UCVA) was 0.4, and Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) was 0.6 with a refraction of +0.50 D sphere and −1.50 D cylinder at an axis of 101°. In the left eye, UCVA was 0.1, and BCVA was 0.2 with a refraction of +0.75 D sphere and −1.00 D cylinder at an axis of 65°. Furthermore, a marked improvement in corneal morphology was also observed. Corneal edema largely resolved, resulting in excellent corneal clarity in the right eye and satisfactory clarity in the left eye. Pachymetry measurements yielded 532 µm for the right eye (Figure 7A) and 661 µm in the left eye (Figure 7B). Given the improvement in corneal status, the planned DSAEK was deferred.

Figure 7: Postoperative spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in the right and left eye. A. In the right eye, the central corneal thickness is 532 µm. B. In the left eye, the central corneal thickness is 661 µm.

Deepening of the anterior chamber and widening of the iridocorneal angle following the cataract surgeries resulted in a reduced intraocular pressure of 9 mmHg in the right eye and 10 mmHg in the left eye, as measured with iCare tonometry. Anterior segment OCT results are shown in Figure 8A and 8B.

Figure 8: Postoperative swept-source optical coherence tomography of the right and left eye. A. In the right eye, the depth of the anterior chamber to the corneal endothelium is 3.77 mm (white double-headed arrow). B. In the left eye, the depth of the anterior chamber to the

corneal endothelium is 3.78 mm (white double-headed arrow).

Four months after surgery on both eyes, the patient continued topical therapy for both eyes with dorzolamide (Rozalin, Adamed Pharma S.A. Pieńków, Poland) once daily, sorbitol-containing hypertonic eye drops to reduce corneal edema (Cornesin, NTC s.r.l., Milan, Italy eye drops five times daily, and 0.1% dexamethasone once daily. In addition, a hypertonic Cornesin ophthalmic ointment (NTC s.r.l., Milan, Italy) containing 4.5% sodium chloride was prescribed for the left eye at bedtime. Following these treatments, the patient resumed independent functioning.

Discussion

When selecting a surgical technique for advanced, dense cataracts, particular attention should be paid to surgical and clinical outcomes, including corneal edema, endothelial cell loss, surgically induced astigmatism, glaucoma, hypotony, intraoperative adverse events, and other complications. Phacoemulsification uses ultrasound energy to fragment the opacified crystalline lens into small pieces, which are aspirated through a small incision, typically 2.2-3.0 mm in width. Consequently, the wound often does not require suturing and heals rapidly, resulting in a short postoperative recovery time and a low rate of surgically induced astigmatism. This technique is particularly advantageous in cases of standard cataracts of soft to moderate nuclear density. However, ultrasound energy poses a significant risk in cases of dense, brunescent cataracts, when endothelial cell loss during phacoemulsification might be substantial. Corneal endothelial cells do not regenerate, and their loss is irreversible. Excessive ultrasound energy can cause thermal and mechanical injury, potentially resulting in a critical reduction in endothelial cell density, corneal decompensation, chronic corneal edema, and permanent corneal opacity, ultimately necessitating keratoplasty. In contrast, ECCE and MSICS avoid this mechanism of injury, as the hard lens nucleus is completely extracted without using ultrasound energy [18]. ECCE involves making a large corneal incision, typically 10-12 mm in width, which permits manual extraction of the lens nucleus in one or two fragments. This method eliminates the need for ultrasound energy; however, it requires suturing and is associated with slower visual rehabilitation. ECCE also carries the highest risk of surgically induced astigmatism due to the substantial incision size and its impact on corneal curvature [19]. In addition, a large superior incision might disrupt the architecture of the iridocorneal angle and affect intraocular pressure, which is less likely to occur with MSICS [20]. Lens stability depends on the integrity of zonular fibers. Their weakening due to aging, trauma, or genetic disorders increases the risk of complications during phacoemulsification, requiring intensive lens manipulation within the capsular bag. Ultrasound vibrations and mechanical forces might lead to zonular dialysis, lens subluxation, and, consequently, vitreous prolapse, increasing the risk of retinal detachment. The wide surgical access in ECCE and MSICS allows for controlled removal of the lens nucleus while stabilizing intraocular structures.

This facilitates safe implantation of an IOL, even when zonular support is compromised. For this reason, ECCE, particularly MSICS, is often considered a safer surgical option in patients with known or suspected zonular weakening than phacoemulsification. MSICS is a modern, sutureless, manual modification of ECCE that employs a smaller (6-8 mm) incision and a self-sealing scleral tunnel. This approach does not require sutures, thereby improving wound stability and reducing surgically induced astigmatism. The technique is particularly effective and safe for hard cataracts. Compared with conventional ECCE, MSICS is characterized by superior wound stability, lower astigmatism, faster healing [21], and faster recovery of visual acuity. The safety of MSICS is partly due to the protection of the posterior capsule through controlled nucleus stabilization and the effective safeguarding of the corneal endothelium with sufficient viscoelastic material. MSICS is considered safe for the corneal endothelium for dense cataracts as phacoemulsification is for soft cataracts, and is nearly as effective in terms of functional outcomes [16]. Therefore, MSICS may be considered an optimal intermediate option between phacoemulsification and conventional ECCE. MSICS is especially advantageous for high-risk patients, including those with very dense cataracts, hard lens nuclei, or pre-existing corneal damage, where phacoemulsification poses significant risks. An experienced surgeon, proficient in multiple surgical techniques, can select the safest method for each patient, even at the cost of slower visual rehabilitation. The outcomes of cataract surgery are traditionally evaluated using objective parameters, such as BCVA and contrast sensitivity. Both phacoemulsification and MSICS lead to significant postoperative improvement in BCVA [22], and patients achieve very good functional outcomes with a low complication rate [23]. In summary, the available literature indicates that MSICS is an effective and safe surgical technique, providing functional outcomes comparable to those of phacoemulsification while offering advantages over conventional ECCE. In complicated cases and in dense cataracts, ECCE and, particularly, MSICS often represent a safer therapeutic option.

Conclusion

The primary goal of cataract surgery is to restore visual acuity, and its success depends not only on the effective removal of the opacified lens but also on minimizing intraoperative and postoperative complications. The choice of surgical technique has a significant impact on final functional outcomes; therefore, careful evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of the available cataract surgery methods is essential. The ultimate therapeutic objective is to optimize visual acuity while minimizing corneal endothelial cell loss and preventing corneal decompensation. MSICS is also employed as a “rescue” procedure in severe cataract cases that are difficult to manage using standard protocols. It enables cataract surgery to be performed in eyes with compromised corneal clarity, e.g., as a first-stage procedure before posterior lamellar DSAEK. In such cases, attempts at phacoemulsification carry a high risk of corneal decompensation and serious complications, including posterior capsule rupture and displacement of lens material into the vitreous cavity, which may ultimately necessitate an additional surgical intervention, i.e., pars plana vitrectomy. Double-incision MSICS proved beneficial for our patient, as it enabled the removal of an exceptionally dense lens nucleus under very challenging anatomical conditions, including extreme shallowing of the anterior chamber. The procedure was performed without ultrasound energy, thereby protecting the fragile, decompensated cornea. MSICS represents a favorable alternative to phacoemulsification in difficult cataract cases, such as brunescent cataracts, hard-lens nuclei, zonular weakness, or situations requiring corneal endothelial protection. Compared with conventional ECCE, MSICS provides better visual acuity improvement, lower postoperative refractive astigmatism, and a lower rate of ocular complications. Different cataract surgery techniques have distinct roles in clinical practice and should be selected based on the patient’s risk profile and the eye’s anatomical condition.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Ł.D.; methodology, Ł.D.; software, Ł.D. and D.Ś.; validation, Ł.D., D.Ś. and M.D.; formal analysis, Ł.D. and D.Ś.; investigation, Ł.D. and D.Ś.; resources, Ł.D. and D.Ś.; ´data curation, Ł.D., D.Ś., M.D. and D.W.-P.; writing original draft preparation, Ł.D., D.Ś; writing review and editing, Ł.D., D.Ś., M.D. and D.W.-P.; visualization, Ł.D. and D.Ś.; supervision, Ł.D. and D.W.-P.; project administration, Ł.D., D.Ś., M.D. and D.W.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient Consent for Publication: The patient consented to the publication of the case.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: No approval from the Bioethics Committee is required. Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable

Funding: This study received no specific funding.

References

- Upasani D, Daigavane S (2024) Phacoemulsification Techniques and Their Effects on Corneal Endothelial Cells and Visual Acuity: A Review of “Direct-Chop” and “Stop-and-Chop” Approaches Under Topical Anesthesia. Cureus 16: e66587.

- Kaczorowska N, Kaczorowski K, Goździewic T (2020) New techniques in cataract treatment (in Polish). Okulistyka po Dyplomie 3.

- Gurnani B, Kaur K (2025) Phacoemulsification. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL).

- Younus O, Lockington D (2023) Comparison of phacoemulsification ultrasonic power between the phaco-chop and the divide-and-conquer techniques: a mini-systematic review. Eye 37: 3865-3868.

- Lee SH, Chiu YC, Tsai PC, Wang JH, Chiu CJ (2025) Femtosecond laserassisted cataract surgery versus conventional phacoemulsification cataract surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scientific reports 15: 27569.

- Rosen H, Vernon SA (2022) Unexpected Poor Vision within 24 h of Uneventful Phacoemulsification Surgery-A Review. Journal of clinical medicine 12.

- Ramirez-Garcia MA, Khalifa YM, Buckley MR (2018) Vulnerability of corneal endothelial cells to mechanical trauma from indentation forces assessed using contact mechanics and fluorescence microscopy. Exp Eye Res 175: 73-82.

- Park S, Leonard BC, Raghunathan VK, Kim S, Li JY, et al. (2021) Animal models of corneal endothelial dysfunction to facilitate development of novel therapies. Annals of translational medicine 9: 1271.

- Kunzmann BC, Wenzel DA, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Spitzer MS, Schultheiss M (2020) Effects of ultrasound energy on the porcine corneal endothelium - Establishment of a phacoemulsification damage model. Acta Ophthalmol 98: e155-e160.

- Geng W, Lin W, Song P, Zhang M, Wu J, et al. (2022) Effect of Anterior Chamber Instability during Phacoemulsification Combined with Intraocular Lens Implantation. Journal of ophthalmology 2022: 2848565.

- Meek KM, Knupp C (2015) Corneal structure and transparency. Prog Retin Eye Res 49: 1-16.

- Pirahanchi Y, Jessu R, Aeddula NR (2025) Physiology, Sodium Potassium Pump. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL).

- Chen K, Xu WY, Sun SS, Zhou HW (2023) Corneal endothelial cells and acoustic cavitation in phacoemulsification. World J Clin Cases 11: 1712-1718.

- Briceno-Lopez C, Burguera-Gimenez N, Garcia-Domene MC, DiezAjenjo MA, Peris-Martinez C, et al. (2023) Corneal Edema after Cataract Surgery. Journal of clinical medicine 12.

- Zitha AJ, Rampersad N (2022) Cataract surgery outcomes: comparison of the extracapsular cataract extraction and manual small incision cataract surgery techniques. Afr Health Sci 22: 619-629.

- Abdellaoui T, Sebbata S, Mouzari Y, Oubaaz A (2023) Manual small incision cataract surgery in dense cataract: Morocco comparative study. Ophthalmology Jounal 8: 118-121.

- Signes-Soler I, Javaloy J, Munoz G, Moya T, Montalban R, et al. (2016) Safety and Efficacy of the Transition from Extracapsular Cataract Extraction to Manual Small Incision Cataract Surgery in Prevention of Blindness Campaigns. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 23:187-194.

- Gajraj M, Mohan A (2022) Safety and efficacy of manual small-incision cataract surgery in patients with brunescent and black cataracts and other ocular comorbidities. Indian J Ophthalmol 70: 3898-3903.

- George R, Rupauliha P, Sripriya AV, Rajesh PS, Vahan PV, et al. (2005) Comparison of endothelial cell loss and surgically induced astigmatism following conventional extracapsular cataract surgery, manual small-incision surgery and phacoemulsification. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 12: 293-297.

- Onakpoya OH, Adeoye AO, Adegbehingbe BO, Badmus SA, Adewara BA, et al. (2020) Intraocular pressure variation after conventional extracapsular cataract extraction, manual small incision cataract surgery and phacoemulsification in an indigenous black population. Pan Afr Med J 36: 119.

- Chauhan RA, Agrawal SO, Sawarkar RR, Agrawal S (2022) Comparative study between conventional and 4 mm manual smallincision cataract surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol 70: 3879-3882.

- Goel A, Das M, Sen S (2024) Comparative Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery Versus Phacoemulsification for Brown Cataracts. Cureus 16: e75260.

- Ruit S, Tabin G, Chang D, Bajracharya L, Kline DC, et al. (2007) A prospective randomized clinical trial of phacoemulsification vs manual sutureless small-incision extracapsular cataract surgery in Nepal. American journal of ophthalmology 143: 32-38.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.