Malignant and Premalignant Changes in Juvenile Zebrafish Exposed to A Human Sarcoma-Derived Cells-Free Filtrate

by Fernandez-Puentes S1, Nasruddin NS2, Arteaga-Hernandez E3, GarciaOjalvo A4, Millares-López R5, de Armas-Fernández MC6, CampalEspinosa A7, Sánchez-Miralles T1, Morin-Fanego K1, Pino-Fernandez G4, Casillas-Casanova D4, Núñez-Figueredo Y1, Berlanga-Acosta J4*

1Drug Research and Development Center. Ave. 26 No. 1605 e/ Boyeros y Puentes Grandes Plaza de la Revolución. La Habana. Cuba. C.P: 10400.

2Department of Craniofacial Diagnostics & Biosciences, Faculty of Dentistry Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz 50300 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

3Department of Pathology. Hospital Hermanos Ameijeiras. San Lázaro No. 701 esquina a Belascoaín. Centro Habana, La Habana. Cuba. C.P.: 10200

4Centro de Ingeniería Genética y Biotecnología. Ave 25 S.N. e/158 y 190. Cubanacán, Playa. Cuba. C.P.: 11300.

5Department of Pathology. Clínica Central Cira García Calle 20 No. 4101 esq. a Av. 41 Miramar, Playa, La Habana, Cuba. C.P.: 11300.

6Department of Pathology. Center for Medical and Surgical Research. Calle 216 y 11 B Rpto Siboney, Playa, La Habana, Cuba. C.P.: 11300.

7Centro de Ingeniería Genética y Biotecnología. Circunvalación Norte y Ave. Finlay, Camagüey, Cuba. C.P.: 70100.

*Corresponding author: Berlanga-Acosta J, Centro de Ingeniería Genética y Biotecnología. Ave 25 S.N. e/158 y 190. Cubanacán, Playa. Cuba. C.P.: 11300.

Received Date: 06 January, 2026

Accepted Date: 16 January, 2026

Published Date: 21 January, 2026

Citation: Fernandez-Puentes S, Nasruddin NS, Arteaga-Hernandez E, Garcia-Ojalvo A, Millares-López R, et al. (2026) Malignant and Premalignant Changes in Juvenile Zebrafish Exposed to A Human Sarcoma-Derived Cells-Free Filtrate. J Oncol Res Ther 11:10325. https://doi.org/10.29011/2574-710X.10325

Abstract

Malignant transformation is a multi-step process driven by genetic and epigenetic signalers that ultimately impose “tumor organs”. Continuing our studies on the effect of cells-free filtrates derived from human malignant tumors, we examined the consequences of administering to juvenile adult zebrafish a cell-free filtrate elaborated from an invasive sarcoma. Surgical tumor samples were mechanically disrupted, centrifuged, and filtered. Protein concentration was used as arbitrary unit for the treatments. The debris-free, acellular homogenate was intraperitoneally administered twice a week for 6 weeks to 20 specimens. Concurrent control groups received a cells-free homogenate from healthy donors´ tissue and normal saline. Four to six weeks of sarcoma homogenate administration led to the onset of progressive abdominal dilation, swimming activity reduction, spinal deviation, and cutaneous dark spots. The zebrafish were terminated on week 8. Whole-body samples were formalin fixed, decalcified, paraffin-embedded, and 3-4 µm sectioned. Serial tissue sections were hematoxylin/eosin stained and blindly examined. The sarcoma filtrate triggered premalignant and malignant changes that included gastrointestinal tumors with sarcomatous aspect, hepatocellular carcinoma, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a poorly differentiated tumor made up by cells of epithelioid aspect, multinodular foci of bile ducts hyperplasia with or without epithelial atypia, and perinodular collagen accumulation. Langerhans islets hyperplasia with nuclear atypia was also observed. None of these changes were ever detected in control groups. This study confirmed and extended our hypothesis that human cancers cell-free filtrates contain “malignancy drivers” that may implement a carcinogenesis process, overriding inter-species barriers, and provoking premalignant and malignant lesions in a non-mammalian, aquatic organism.

Keywords: Zebrafish; Carcinogenesis; Cancer; Sarcoma; CellsFree Filtrate.

Introduction

Carcinogenesis is a broad process of cellular transformation that stems from variegated genetic alterations, including loss and gainof-function through driver mutations that can ordinarily occur in one single cell [1, 2]. Thereafter it ensues a stepwise sequence of cellular changes from initiation, promotion, and progression that ultimately translate in supraphysiological capabilities for survival, proliferation, dissemination, dormancy, and recurrence [3, 4]. All these processes are also led by an extensive and continuous reediting process of the epigenetic code, rendering a particular cancer landscape with wide plasticity [5]. Immortality, metabolic reprogramming, immune-edition, and autonomy are also hallmarks of malignant transformed cells [4, 6, 7]. Furthermore, epigenetic rearrangements appear to drive cancer cells events of dedifferentiation and trans differentiation, distancing the cells from their original histotype [8, 9]. These events have frequently puzzled pathologists for years given the cancer markers of atypia, pleomorphism, and morphological heterogeneity [10], all of them, resulting from a cellular adaptative response to microenvironmental pressures. These outstanding hallmarks [11, 12], have poised cancer for centuries as the emperor of maladies [13].

In order to asses our hypothesis on the existence of a “pathologic cellular memory” behind the clinical course and phenotype of chronic noncommunicable diseases, we undertook a decade ago the investigation of the concept of diabetic metabolic memory transmissibility, and the subsequent onset of diabetic complications in healthy animals [14]. The inaugural study demonstrated that histopathological traits of diabetic skin and ulcers granulation tissue, could be faithfully recreated in rats through the administration of cell-free filtrates (CFFs) prepared from human fresh diabetic tissue samples [14]. Thereafter, we reproducibly demonstrated that CFFs derived from human pathologic tissue surgical samples, contain “chemical codes” of other forms of non-communicable diseases as arteriosclerosis [15], and cancer [16, 17], and that these signallers could be extracted, passively transferred to otherwise healthy animals, and accordingly recapitulate the histopathological hallmarks of the human donor´s condition [18]. We showed that malignant tumors-derived CFF is able to induce premalignant and malignant changes in different organs, in a relatively narrow temporary window in nude mice [17]. The findings of a subsequent independent and extemporaneous study included the onset of lung, and pancreatic adenocarcinomas, thyroid, renal, and skin carcinomas, an undifferentiated sarcoma, and a variety of preneoplastic changes using different tumor histotypes for the CFF elaboration [16]. These experiments suggested that a malignant transformation code exists, and that this tumorigenic message disrupted cellular proliferation and differentiation programs of normal, mature populations of epithelial and mesenchymal cells in otherwise normal nude mice. More interestingly is the finding that all these changes occurred irrespective to the natural interspecies barriers, suggesting that the cancer genetic and/or epigenetic signallers may be horizontally transferred from eukaryotic-toeukaryotic in mammals’ organisms [16, 17].

Danio rerio, commonly known as zebrafish (ZF), is an animal model first used in research in the early 1980s for the study of developmental biology, and subsequently introduced for cancer research as early as 1982. With the advent of transgenic and mutant models through relative technological simplicity, zebrafish has become a precious biomodel for the study of cancer biology, as for the preclinical evaluation of its pharmacological candidates [1921]. A variety of experimental carcinogenesis approaches spanning from chemicals carcinogens, xenotransplantation of human tumor cells, up to fine and selective genetic manipulation have been successfully implemented in zebrafish [22-25]. No previous study has examined however, the outcomes in ZF resulting from administering an acellular homogenate elaborated from the tissue of a human malignant tumor. We consequently interrogated whether the events of malignant transformation observed in nude mice and possibly due to tumors-derived oncogenic primers, could provoke cancer in an aquatic, non-mammalian specimen. It is shown here that the CFF elaborated from a lethal pleomorphic sarcoma and administered for a few weeks, accounted for a collection of premalignant and malignant changes in the recipient fishes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

All the animal procedures were conducted according to local and International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research. This study was developed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, and the Center for Investigation and Medicines Development (CIDEM), which is the venue of the ZF aquaculture laboratory.

Preparation of cell-free filtrates:

The collected sarcoma surgical samples were allowed to thaw and weighed, and approximately 100 mg of wet tissue placed in a 2-mL vial containing 1 mL of normal saline, which was homogenized using a TissueLyser II for 3 min at 30 revolutions/second. The sample was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, sterilized by filtration using 0.2-μm nitrocellulose filters (Sartorius Lab Instruments), aliquoted into sterile Eppendorf vials, and stored at −70°C. As for all the previous studies conducted so far, protein concentration was used as the arbitrary unit of measurement to prepare and administer the inoculums.

CFF biochemical characterization

All the biochemical parameters were determined by spectrophotometric methods using commercial kits. Proinflammatory markers included C-reactive protein (CRP) [C Reactive Protein (PTX1) Human ELISA Kit, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom], interleukin (IL)-1β (IL-1 beta Human ELISA Kit, Abcam, Mass, United States), IL-6 (IL-6 Human ELISA Kit, Abcam), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (Human TNF alpha ELISA Kit, Abcam). Oxidative stress markers included malondialdehyde (MDA) [Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit, Abcam] and H2O2 (Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit, Abcam). Additionally, Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) levels were determined using the ELISA Kit for SIRT1 (Cloud-Clone Corp., Houston, Texas, United States). In all cases, the manufacturer’s instructions were followed.

Zebrafish husbandry

Wild-type adult ZF were maintained following the established protocols described in previous studies [26]. The aquarium conditions included a recirculating aquatic system with constant oxygenation, controlled environmental conditions, including a 14-hours light/10-hour dark cycle, water temperature of 28°C, and pH maintained at 7.2-7.5. The fishes were fed twice daily with commercial zebrafish food (TetraMin Flakes), and the water quality parameters regularly monitored to ensure optimal conditions for breeding and embryo development. Body weight was registered a day before the study commencement, on a bi-weekly basis, and before termination.

CFF administration to juvenile ZF

Three experimental groups of 20 ZF each were formed. One group received the sarcoma-derived CFF, while the concurrent controls received healthy donor-derived cutaneous tissue CFF, and normal saline solution. Animals received 20µg of protein in 10µL of normal saline solution from each type of tissue source. ZF were about 2-3 months post-fertilization (mpf) during the inoculation period which extended from week 5 to 10. Administrations were done twice a week with a 10µL-Hamilton syringe, through intraperitoneal injection once the animals were sedated by progressive water cooling to 8-10 degrees [27].

Animals’ termination, tissue processing, and histopathologic examination

ZF were euthanized two weeks after the end of the administration period. Gross external changes as spine deviation, brown-reddish skin macules, and abdominal dilation were individually registered. ZF were deeply anesthetized [28] with lidocaine (350mg/L) and immersed in 10% neutral formalin solution, dehydrated, and paraffin embedded. Sections at 4-5 μm thickness were generated and subsequently deparaffinized, rehydrated and stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and eosin [29]. The slides were captured using a BX53 Olympus microscope coupled to a digital camera and central command unit (Olympus Dp-21). Histological examinations were blindly and independently performed by a skilled ZF board certified experimental pathologist and by a specialist in human anatomical pathology with documented experience in animal models histopathology. Considering that liver cancer is an umbrella term for different types of tumors, previously established histopathological criteria for ZF were consulted for the diagnosis [30, 31].

Results

1-Cells-free filtrate biochemical characterization

An elemental descriptive characterization of the sarcoma-derived CFF is shown in table 1 in reference to healthy donor skin CFF, used as a concurrent control. The biochemical characterization included a marker of lipid peroxidation (MDA), pro-inflammatory reactants (CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α), and an overexpressed growth factor in human soft tissue sarcoma (VEGF). The resulting data indicated that: (1) the accumulation of membrane peroxidated polyunsaturated fatty acids as determined by the MDA content, is almost three times higher in the sarcoma sample than in the healthy donor control. (2) the sarcoma-derived CRP content is 4.8 superior than the concentration calculated for the healthy donor control tissue. (3) IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations were 4 and 15 folds (respectively) higher than the values calculated for the healthy control. Finally, tumor homogenate VEGF concentration was 4-fold higher than those found in the healthy control.

|

CFF samples |

Protein yield (mg/mL) |

MDA/mg prot. (nmol/mg) |

CRP/mg prot. (ng/mg) |

IL-6/mg prot. (pg/mg) |

TNF-α/mg prot. (pg/mg) |

VEGF/mg prot. (pg/mg) |

|

Healthy skin |

1.71 |

0.135 |

14.04 |

0.326 |

3.43 |

6.34 |

|

Pleomorphic sarcoma |

0.85 |

0.397 |

67.66 |

1.32 |

51.92 |

25.45 |

|

CFF: cell-free filtrate, MDA: malondialdehyde, CRP: C-reactive protein, IL-6: interleukin 6, TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor alpha, VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor. |

||||||

Table 1: Biochemical characterization of the cell-free filtrates (CFF).

2-External gross changes in sarcoma-treated ZF.

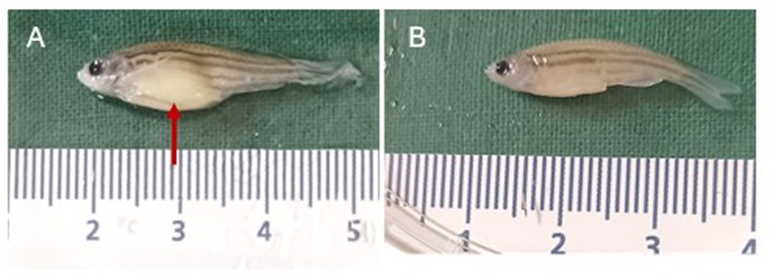

Juvenile ZF exposed to the sarcoma-derived CFF showed the presence of a growing abdominal white mas, associated to skin reddish brown spots, and spinal cord deviation that somehow limited swimming activity (figure 1).

Figure 1: Clinical appearance of juvenile ZF. (A) Specimen representative of the ZF treated with the sarcoma-derived CFF at 6th week. The red arrow indicates the abdominal dilation due to a growing mass. (B) Representative of the normal appearance of specimens treated with the healthy donor tissue CFF.

As shown in table 2, the sarcoma administration produced a significant fall in body weight at the second week of administration. Although no significant differences were detected as compared to the concurrent controls from that point on, this group showed the lowest weights registered.

|

Time (weeks) |

Body weight (mg) |

||

|

Saline |

Healthy skin |

Tumor |

|

|

0 |

281.55 ± 17.49 |

281.25 ± 17.41 |

281.75 ± 15.58 |

|

2 |

281.05 ± 17.26 a |

278.20 ± 17.71 ab |

267.75 ± 15.58 b |

|

4 |

279.95 ± 16.51 |

281.25 ± 17.81 |

272.95 ± 17.82 |

|

6 |

280.35 ± 16.70 |

279.90 ± 17.18 |

273.70 ± 18.10 |

|

8 |

280.30 ± 16.52 |

280.20 ± 17.15 |

272.75 ± 16.21 |

Table 2: Zebrafish body weight.

Data are expressed as media ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

3-Histological findings

Administering the sarcoma-derived material for six weeks resulted in the onset of pre-malignant and malignant changes that involved intestine, liver, and pancreas (table 3).

|

Organ |

Findings description |

Incidence (N=16 fishes *) |

|

Intestine |

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors with sarcomatous aspect, including spindle cells within the core of the tumor mass |

6 (37,5%) |

|

Intestine |

Intestinal Goblet cells hyperplasia |

16 (100%) |

|

Intestine |

Muscularis externa layer hyperplasia |

12 (75%) |

|

Liver |

Poorly and moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinomas |

5 (31,2%) |

|

Liver |

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas evoking an intraductal tubulopapillary pattern |

4 (25%) |

|

Liver |

Proliferative multinodular foci of bile ducts hyperplasia with or without epithelial atypia and peritubular, perinodular collagen bundles accumulation evoking a biliary adenofibroma |

9 (56,2%) |

|

Pancreas |

Langerhans islets hyperplasia |

3 (18,7%) |

|

Pancreas |

Poorly differentiated tumor made up by cells of epithelioid aspect |

1 (6,2%) |

|

(*) These findings derive from 16 fishes terminated and adequately processed for histopathological analysis. The four fishes found dead during the first 2 weeks of inoculation were excluded. |

||

Table 3: Main histological changes associated to sarcoma CFF administration.

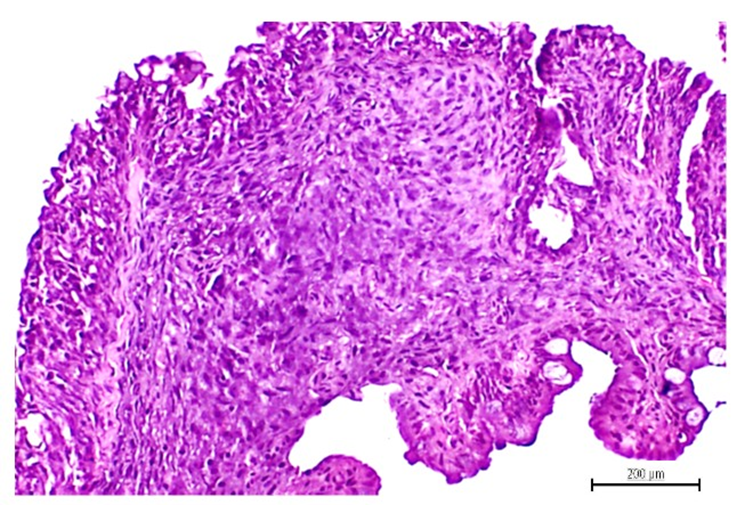

Intestinal stromal-like tumors (figure 2) were identified as a submucosal mass of varied size that produced organs dysmorphia, with a well circumscribed intramural nodular aspect in the muscularis propria, exhibiting dense extracellular matrix, and predominantly made up by spindle cells. The nuclei appeared clearly pleomorphic, atypic, and surrounded by a dense aspect-cytoplasm. Goblet cells and muscularis externa hyperplasia were also observed in different intestinal samples.

Figure 2: Intramural intestinal stroma tumor exhibiting a sarcoma-like aspect with abundant spindle cells. The nuclei appeared intensely basophilic, pleomorphic, atypic, and surrounded by a dense aspect-cytoplasm. H/E, magnification x 40. Scale bar 200 µm.

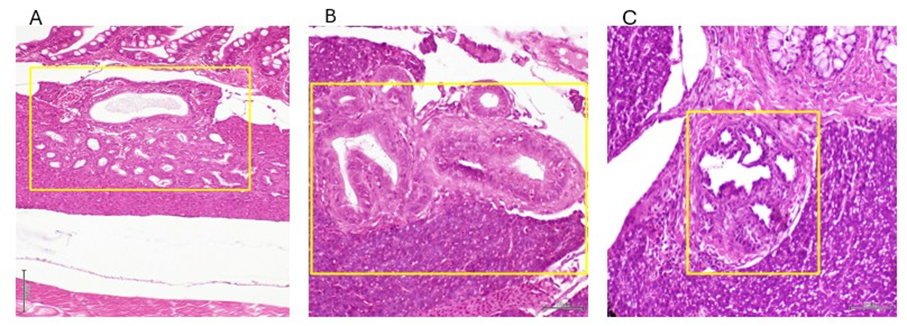

Liver cells homeostasis was also affected by the tumor-derived signalers. Hepatic premalignant lesions included multiple and scattered parenchymal nodules reminding an adenomatous pattern, containing numerous hyperplastic biliary tubules of varied shape and size (figure 3). Most of these neoformed tubules exhibited luminal papillary neoformations, were lined by cuboidal cholangiocytes arranged as a simple epithelial or as abnormally stratified layers. Within the cholangiocytes layer, dysplastic cells were often observed, with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei. These foci of tubules hyperplasia were surrounded by thick collagen bundles and cells of spindle morphology with basophilic nuclei.

Figure 3: Image representing the different histological patterns of intrahepatic nodules with bile ducts hyperplasia. A – shows into the yellow rectangle a nodule with multiple neoformed tubules including a giant one (magnification x 4). B – the yellow rectangle highlights two giant ducts, the left one with a notable papillary formation. On the right, a ductus shows a stratified epithelia with cholangiocytes hyperplasia (magnification x10) . C – the box encircles a giant ductus with multiple papillary neoformations with cuboidal cholangiocytes with hyperchromatic nuclei (magnification x 10). In general terms these represent tubular and papillary proliferation reminiscent of an adenoma pattern. H/E staining. Scale bar 200 µm.

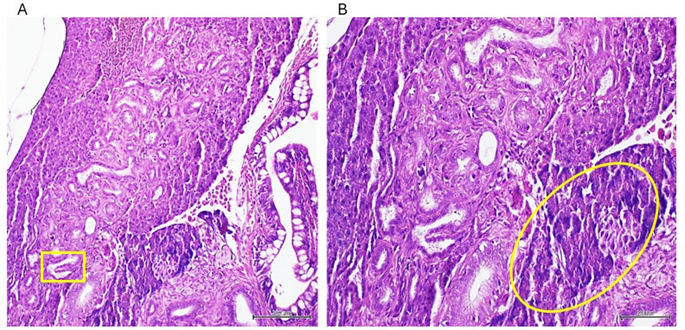

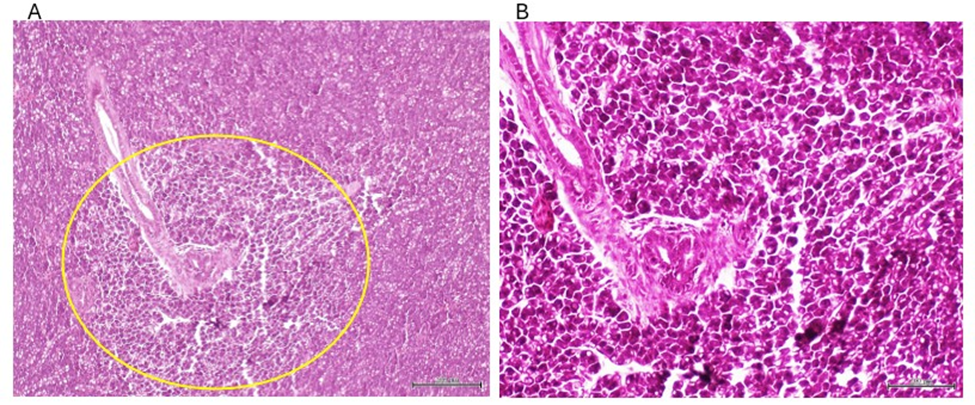

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (ICC) were detected in fishes exposed to the sarcoma homogenate. These lesions exhibited a tubular pattern with well-to-moderate differentiation, marginal atypia, and embedded within areas of desmoplastic reaction (figure 4). Hepatocytes-originated malignancies consisted in typical hepatocarcinomas (HCC). These tumors were clearly distinguished by loss of hepatocytes cohesiveness (figure 5), perinuclear vacuolation with areas of signet ring cell features, sporadic fibrotic induration with collagen bundles, nuclear atypia, and particularly by the loss of hepatocyte plate structure with tendency toward a nesting pattern of organization. Another interesting finding consisted in a nest of atypical epithelioid cells at the edge of the organ´s parenchyma. These cells appeared rounded, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and eccentric nuclei, indicating mild to moderate nuclear atypia (not shown).

Figure 4: Images representing an intrahepatic biliary carcinoma with tubular histological pattern. A: the yellow box indicates a papillary neoformation. B: there is a noticeable focus of poorly differentiated cells with hyperchromatic and atypic nuclei encircled to the bottom right. Areas of desmoplastic reaction are observable around the neoformed biliary ducti (magnifications x10 and x 20) H/E staining. Scale bar 200 µm.

Figure 5: Sarcoma-derived CFF induced malignant transformation of hepatocytes with multiple hepatocarcinomas in this group. A: loss of hepatocytes discohesiveness and some degree of cellular disorientation is observable within the circle. B: Perinuclear vacuolation, areas of signet ring-like cells, hyperchromatic and atypic nuclei, and cellular pleomorphism are distinguished. Magnification x 10 and x 40. H/E. Scale bar 200 µm.

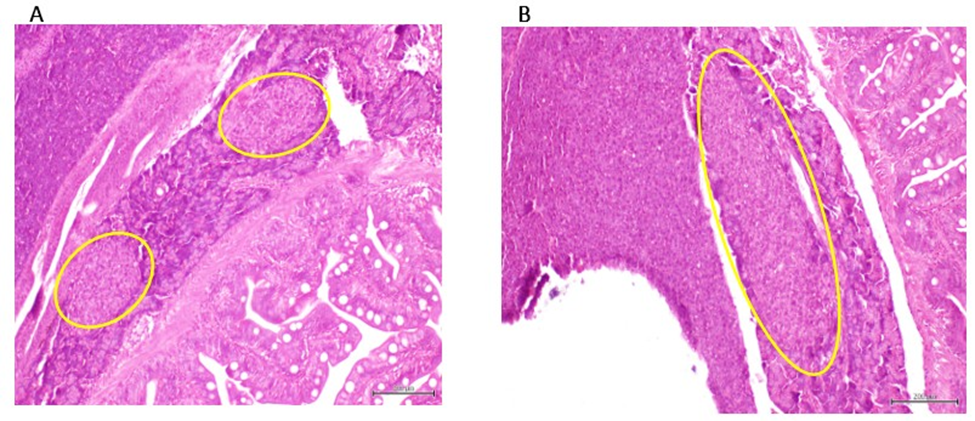

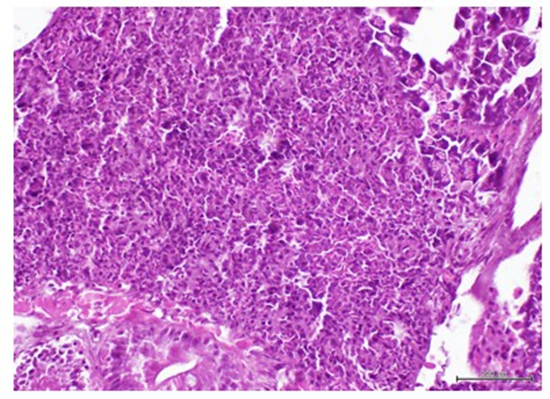

Pancreatic changes included: (1) a remarkable Langerhans islets hyperplasia as compared to healthy donor-matched control (figure 6), and (2) the presence of a highly undifferentiated tumor of possible epithelial origin, outside the intestinal wall and adjacent to the exocrine pancreas. This tumor is a typical overcrowded nodule of poorly differentiated, irregular-in-shape cells of epithelioid morphology, and features of high-grade malignancy. The cells are characterized by marked stacking, intense basophilia, pleomorphic nuclei, variable cytoplasm appearance and no inflammatory response (figure 7). None of these lesions were observed in the group of ZF treated with the healthy donors CFF, or in the saline group.

Figure 6: A: Representative of the aspect of a Langerhans islet in ZF treated with CFF derived from healthy donors. B: Representative of hyperplastic response of Langerhans islet in ZF treated with the sarcoma-derived CFF. Magnification x 10. H/E. Scale bar 200 µm.

Figure 7: Image showing a poorly differentiated tumor of possible epithelial origin adjacent to the exocrine pancreas. Hypercellularity, architectural disorganization, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism are shown. H/E. Magnification X 40. Scale bar 200 µm.

Discussion

Previous studies from our group based on the administration of CFF prepared from malignant tumors, pointed to the existence of soluble and transferable tumor tissue-derived effectors that disrupted cell proliferation and differentiation programs, and ultimately induced a variety of premalignant and malignant lesions in otherwise healthy nude mice. In these studies, epithelial and mesenchymal tumors proved to be irreversible, metastasizing, and endowed with autonomous progression [17], which met with the contemporary concepts of tumors hallmarks [32]. Continuing our studies in the line of a hypothetical existence and passive transmissibility of a cellular pathologic memory for chronic, non-communicable diseases, we recently examined the putative impact of these theoretical “oncogenic drivers” in ZF, embryos. The embryos exposed for 60 hours to a mammary carcinoma CFF exhibited a collection of morphogenetic anomalies, and most importantly, the neoplastic markers c-Myc and HER-2 were expressed by developing structures; all of this, in stark contrast to embryos exposed to healthy donor skin [16].

The present study conducted in juvenile ZF, shows that the sarcoma-derived CFF contained cancer drivers capable of inducing malignant lesions in a relatively short period of time, overriding the intrinsic biological differences, and the interspecies barriers between fishes and humans. The resulting tumors observed in the sarcoma CFF-treated ZF group derive from the habitual experimental methodology used in our previous studies in nude mice [16, 17]. Accordingly, the tumors-derived CFF are prepared through mechanical tissue disruption having sterile saline solution as vehicle, with no purification processes, or any other type of chemical manipulation. Thus, we assume that CFF contains all the cellular ingredients and the donor´s tissue signatures, that have previously demonstrated to impose their pathologic message into the host animal cells, and thereafter recapitulate the histopathologic hallmarks of the donor´s diseased tissue [18]. The fact that despite the mechanical tumor tissue disruption DNA and RNA molecules are detected in the CFF, and that RNA could be successfully reverse-transcribed and amplified, raises the notion of a possible uptake by the host normal cells of some sort of tumorderived genetic, or epigenetic transforming messenger [17].

As mentioned above, the intestinal tract and its accessory glands liver and pancreas were the most permissive target organs for the transforming activity of the sarcoma CFF. Intestinal glandular and muscular hyperplasia, multiple adenomas with bile ducts hyperplasia, intestinal sarcoma, hepatocarcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma were the most frequent histopathological changes observed. Notoriously, studies conducted in nude mice years ago with the same sarcoma sample also targeted the digestive system mucosa, provoking gastric and intestinal hyperplasia (glandular hyperplasia, mucosal dysmorphia, and Goblet cells hyperplasia), serosal duplication of the intestinal mucosa, multiple villous or papillary colon adenomas, and lymphadenomas [17]. The histopathological similitude between the hallmarks characterizing the ZF liver and pancreas premalignant and malignant lesions, and the histological criteria established for laboratory rodents was indeed remarkable [30, 33]. This includes the presence of hepatobiliary fibrosis in both species, a tissue response marker that is often neglected despite its consistent role in the transition from benign to malignant biliary conditions [34]. As a corollary, and in line with the ZF pancreatic changes, we observed in a recent study that nude mice exposed to a CFF derived from a pancreatic adenocarcinoma, exhibited marked hyperplasia of Langerhans islets with nuclear atypia [16]. The molecular mechanisms underlying this overall tissue response commonality are unknown. Nevertheless, they somehow reflect an evolutionary conservation in the pathological patterns of cell and tissue on road to malignant transformation between chordates specimens. Comparative biology studies have shown that ZF intestinal morphology is highly homologues to that of higher vertebrates [35]. Other studies document the ancestral genetic conservation of sensitive cancer genes and cancer driving pathways, between ZF and mammals including humans [36]. Comparative transcriptome profiles analysis between ZF liver cells, mice, and humans revealed the complete conservation of orthologous cell types in ZF that perform identical functions to their human counterparts [37]. Globally speaking, the inter-species reproducibility of these pathological changes is an encouraging finding, considering that the multidimensional intricacy of cell malignant transformation has historically caused variability, heterogeneity, and lack of experimental reproducibility [38].

Since none of these alterations were identified in any of the control groups, suggests that there was no spontaneous tumorigenesis during the experimental period. This also suggests that the neoplastic traits observed, do not represent a form of tissue reactive response to the human xenogeneic material. As a matter of fact, the temporary window when ZF were inoculated corresponds to a period in which the adaptive immune system is incipient [39].

The fact that we have been unable to identify the tumor-derived messengers that may elicit the in vivo carcinogenic response is a major limitation of this and previous studies. Nevertheless, this study, developed in a non-mammal, aquatic, juvenile organism lends support to our hypothesis on the existence of a “malignant code” that overrides species barriers, and that may be passively, horizontally transferred in a eukaryotic-to-eukaryotic manner. Whether the transforming driving force underneath these events, relates to a transfection-like internalization of mutated gain-offunction oncogenes, epigenetic drivers, exosomes, mutated tumor suppressor genes with dominant negative function, or all at the same, is currently subject of intense research [40].

Finally, despite the conflicting views regarding the etiopathogenic role of transmissible viruses in the origin of human cancers [4143], the classic observation by Dolberg and Bissell that for the Rous oncovirus one week after inoculation is sufficient to induce palpable sarcomatous tumours, has enticed our group for a viral agent hunting [44]. Considering that ZF did not show a cachectic consumptive process during the inoculation period, and that animal’s mortality was negligible and reduced to the injection procedure on the early administrations, we accordingly reinforce the usefulness of both the value of tumors CFF as vector of viable carcinogenic drivers, and the ZF as a reliable model for the study of cancer biology.

References

- Nussinov R, Tsai CJ, Jang H (2022) A New View of Activating Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res 82: 4114-4123.

- Waarts MR, Stonestrom AJ, Park YC, Levine RL (2022) Targeting Mutations in Cancer. J Clin Invest 132: e154943.

- Fishbein A, Hammock BD, Serhan CN, Panigrahy D (2021) Carcinogenesis: Failure of Resolution of Inflammation? Pharmacology & Therapeutics 218: 107670.

- Zhu S, Wang J, Zellmer L, Xu N, Liu M, et al. (2022) Mutation or Not, What Directly Establishes a Neoplastic State, Namely Cellular Immortality and Autonomy, Still Remains Unknown and Should Be Prioritized in Our Research. J Cancer 13: 2810-2843.

- Yu X, Zhao H, Wang R, Chen, Y, Ouyang X, et al. (2024) Cancer Epigenetics: From Laboratory Studies and Clinical Trials to Precision Medicine. Cell Death Discov 10: 28.

- Yang J, Shay C, Saba NF, Teng Y (2024) Cancer Metabolism and Carcinogenesis. Exp Hematol Oncol 13: 10.

- Kumari S, Sharma S, Advani D, Khosla A, Kumar P, et al. (2022) Unboxing the Molecular Modalities of Mutagens in Cancer. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29: 62111–62159.

- Jiang H, Jedoui M, Ye J (2023) The Warburg Effect Drives Dedifferentiation through Epigenetic Reprogramming. Cancer biology & medicine 20: 891-897.

- Davies A, Zoubeidi A, Beltran H, Selth LA (2023) The Transcriptional and Epigenetic Landscape of Cancer Cell Lineage Plasticity. Cancer Discov13: 1771-1788.

- Katayama A, Toss MS, Parkin M, Ellis IO, Quinn C, et al. (2022) Atypia in Breast Pathology: What Pathologists Need to Know. Pathology 54: 20-31.

- Saha T, Solomon J, Samson AO, Gil-Henn H (2021) Invasion and Metastasis as a Central Hallmark of Breast Cancer. Journal of clinical medicine 10: 3498.

- Fuji M, Sekine S, Sato T (2024) Decoding the Basis of Histological Variation in Human Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 24: 141-158.

- Suh DH (2012) Book Review: The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 23: 291-292.

- Berlanga-Acost J, Fernández-Mayola M, Mendoza-Marí Y, GarcíaOjalvo A, Playford RJ, et al. (2021) Intralesional Infiltrations of CellFree Filtrates Derived from Human Diabetic Tissues Delay the Healing Process and Recreate Diabetes Histopathological Changes in Healthy Rats. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc 2: 617741.

- Berlanga-Acosta J, Fernández-Mayol M, Mendoza-Marí Y, GarcíaOjalvo A, Martinez-Jimenez I, et al. (2022) Intralesional Infiltrations of Arteriosclerotic Tissue Cells-Free Filtrate Reproduce Vascular Pathology in Healthy Recipient Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23: 1511.

- Berlanga-Acosta J, Arteaga-Hernandez E, Garcia-Ojalvo A, DuvergelCalderin D, Rodriguez-Touseiro M, et al. (2024) Carcinogenic Effect of Human Tumor-Derived Cell-Free Filtrates in Nude Mice. Front. Mol. Biosci 11.

- Berlanga-Acosta J, Mendoza-Mari Y, Martinez-Jimenez I, Suarez-Alba J, Rodriguez-Rodriguez N, et al. (2022) Induction of Premalignant and Malignant Changes in Nude Mice by Human Tumors-Derived CellFree Filtrates. Ann. Hematol. Oncol 9: 1387.

- Berlanga-Acosta J, Fernandez-Mayola M, Mendoza-Mari Y, GarciaOjalvo A, Martinez-Jimenez I, et al. (2022) Cell-Free Filtrates (CFF) as Vectors of a Transmissible Pathologic Tissue Memory Code: A Hypothetical and Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23: 11575.

- Fontana CM, Van Doan H (2024) Zebrafish Xenograft as a Tool for the Study of Colorectal Cancer: A Review. Cell Death Dis 15: 23.

- Cero C, House JS, Verdi V, Ferguson JL, Jima DD, et al. (2025) Profiling the Cancer-Prone Microenvironment in a Zebrafish Model for MPNST. Oncogene 44: 179-191.

- Acanda De La Rocha AM, Berlow NE, Fader M, Coats ER, Saghira C, et al. (2024) Feasibility of Functional Precision Medicine for Guiding Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory Pediatric Cancers. Nat Med 30: 990-1000.

- Chen X, Li Y, Yao T, Jia R (2021) Benefits of Zebrafish Xenograft Models in Cancer Research. Front Cell Dev Biol 9: 616551.

- Wu X, Hua X, Xu K, Song Y, Lv T (2023) Zebrafish in Lung Cancer Research. Cancers 15: 4721.

- Tonon F, Grassi G (2023) Zebrafish as an Experimental Model for Human Disease 24: 8771.

- Kobar K, Collett K, Prykhozhij SV, Berman JN (2021) Zebrafish Cancer Predisposition Models. Front Cell Dev Biol 9: 660069.

- Zhu J, Chen Y, Liu X, Sun Z, Zhang J, et al. (2025) Zebrafish as a Model for Olfactory Research: A Systematic Review from Molecular Mechanism to Technology Application. Food Chemistry 487: 144698.

- Wallace CK, Bright LA, Marx JO, Andersen P, Mullins, MC, (2018) Effectiveness of Rapid Cooling as a Method of Euthanasia for Young Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 57: 58-63.

- Baesso GMM, Venâncio AV, Barca LCV, Peppi PF, Faria CA, et al. (2024) Exploring the Effects of Eugenol, Menthol, and Lidocaine as Anesthetics on Zebrafish Glucose Homeostasis. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 276: 109784.

- Copper JE, Budgeon LR, Foutz CA, van Rossum DB, Vanselow DJ, et al. (2018) Comparative Analysis of Fixation and Embedding Techniques for Optimized Histological Preparation of Zebrafish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 208: 38-46.

- Li Y, Li H, Spitsbergen JM, Gong Z (2017) Males Develop Faster and More Severe Hepatocellular Carcinoma than Females in krasV12 Transgenic Zebrafish. Sci Rep 7: 41280.

- Goessling W, Sadler C (2015) Zebrafish: An Important Tool for Liver Disease Research. Gastroenterology 149: 1361-1377.

- Hanahan D (2022) Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 12: 31-46.

- Yusuf K, Umar S, Ahmed I (2022) Animal Models in Cancer Research. In Handbook of Animal Models and its Uses in Cancer Research; Springer 1-20.

- Shimizu N, Shiraishi H, Hanada T (2023) Zebrafish as a Useful Model System for Human Liver Disease. Cells 12: 2246.

- Brugman S (2016) The Zebrafish as a Model to Study Intestinal Inflammation. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 64: 82-92.

- McConnell AM, Noonan HR, Zon LI (2021) Reeling in the Zebrafish Cancer Models. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 5: 331-350.

- Miao KZ, Kim GY, Meara GK, Qin X, Feng H (2021) Tipping the Scales with Zebrafish to Understand Adaptive Tumor Immunity. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:660969.

- Alekseenko I, Kondratyeva L, Chernov I, Sverdlov E (2023) From the Catastrophic Objective Irreproducibility of Cancer Research and Unavoidable Failures of Molecular Targeted Therapies to the Sparkling Hope of Supramolecular Targeted Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24: 2796.

- Franza M, Varricchio R, Alloisio G, De Simone G, Di Bella S, et al. (2024) Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) as a Model System to Investigate the Role of the Innate Immune Response in Human Infectious Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25: 12008.

- Kennedy MC, Lowe SW (2022) Mutant P53: It’s Not All One and the Same. Cell Death Differ 29: 983-987.

- Bevilacqua G (2022) The Viral Origin of Human Breast Cancer: From the Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) to the Human Betaretrovirus (HBRV). Viruses 14: 1704.

- Steele CD, Abbasi A, Islam SMA, Bowes AL, Khandekar A, et al. (2022) Signatures of Copy Number Alterations in Human Cancer. Nature 606: 984-991.

- Hatano Y, Ideta T, Hirata A, Hatano K, Tomita H, et al. (2021) VirusDriven Carcinogenesis. Cancers 13: 2625.

- Dolberg DS, Bissell MJ (1984) Inability of Rous Sarcoma Virus to Cause Sarcomas in the Avian Embryo. Nature 309: 552-556.

© by the Authors & Gavin Publishers. This is an Open Access Journal Article Published Under Attribution-Share Alike CC BY-SA: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International License. Read More About Open Access Policy.